10. Value Creation through Shaping Opportunity—The Business Model

D. R. Widder is Vice President of Innovation at Philadelphia University, where he is a catalyst for innovation in areas such as entrepreneurship, online learning, analytics, and partnership development. His 20-year career in industry has included multiple high-tech ventures and patents spanning artificial intelligence, medical imaging, and sustainable products, as well as an entrepreneur-in-residence role at IBM. D. R. is on the executive committee of the early-stage venture investment and advisory group RVI. D. R. has a master’s in Engineering with a focus on Applied Mathematics, and an M.B.A. in Entrepreneurship from Babson College.

The gulf between the back-of-the-napkin sketch and achieving business success is bridged by opportunity shaping. Opportunity shaping takes an idea from theoretical greatness to real value delivery and capture. Most of the life cycle of opportunity, from idea to full-scale success, is spent in an opportunity-shaping mode. Shaping opportunity is the difference between an interesting idea and successful execution that creates value for the world.

“No plan survives contact with the enemy” and no opportunity remains unchanged by contact with its stakeholders. An idea must be forged and reshaped as it contacts more of the real-world environment. Contact and feedback from customers, advisors, suppliers, stakeholders, competitive reaction, and macroeconomics shift all test and stress assumptions and execution. The successful entrepreneurial team uses this continual feedback to hone, retool, and its ideas and plans. Teams can outright pivot in a new direction as part of this process (on which David Charron offers greater detail in Chapter 12, “Business Model Execution—Navigating with the Pivot”).

As an opportunity is developed, it needs to be systematically evaluated and refined. This evaluation is composed of the value potential of realized opportunity, the fit of the opportunity internally with the team and externally with the market, the resources needed, and the risks and challenges in reaching the goal.

The evaluation serves three purposes. First, it provides a framework to objectively evaluate all the elements of an opportunity. Entrepreneurs and inventors are necessarily passionate about their ideas, and objective measures will provide an unbiased view of the opportunity and highlight possible weak points. Second, it allows the opportunity to be seen holistically, as customers and other stakeholders will, in order to build support, marshal resources and build a team. Finally, we can use the evaluation to shape the opportunity, highlighting and addressing gaps, to make it stronger.

This chapter provides frameworks and tools for evaluating and refining opportunities. To do this, you need to Map, to Screen, and to Shape (see Figure 10.1). Dimensions of assessment are described and illustrated, as are multiple frameworks that can be used to map and screen concepts. This mapping can provide measures of relative value of opportunities, as well as point to weaknesses and gaps that can be addressed to increase the potential value of an opportunity. Like many of the chapters in this book, this process is iterative.

An opportunity can be viewed through many lenses and perspectives. This chapter lays out some of the most valuable lenses as frameworks. Each can be used with the general iterative processes of Map, Screen, and Shape.

The Dimensions of Opportunity

There are four main dimensions that underlie all the opportunity evaluation frameworks:

1. Value

2. Fit (for both the team and external stakeholders)

3. Resources

4. Risk

We will work through these sequentially even though in practice they should be seamlessly intertwined, as illustrated in the interdependencies articulated in Figure 10.2. As with all the frameworks presented here, they are iterative.

Although it is difficult to decouple components of business model evaluation from the whole, arguably an articulation of the Value Proposition and the Sustainable Competitive Advantage are the most critical components that drive value, fit, resources, and risk.

Value

What is the value of an idea? We will define business models in terms of value creation, value delivery, and value capture. The common theme is obviously value! The first association with value is money, but value includes social value, aesthetic value, political value, and internal and psychological value. The other aspect of value relates to whom the value is provided for. Again, the quick answer is the customer, but a sustainable business model needs to provide value to all the stakeholders involved, including the founders/leaders of the model and key partners.

Strategic Fit

Fit matters both internally and externally. Internally, what is the fit of the opportunity with the founders’ (individual, team, and/or organization) resources, skills, and expertise? Externally, what is the fit of the opportunity with stakeholders, including resource providers (investors, management), value chain components (suppliers, distributors, channels), and, most important, customers? (Chapters 8, “Design Process and Opportunity Development,” and 9, “Navigating Spaces—Tools for Discovery,” explored the process of discovery for unmet needs of users and customers.)

Within the fit-to-market needs, what is the sustainable competitive advantage of the value proposition? The value proposition is why the customer will desire the offering. The sustainable competitive advantage is how you can create it, deliver it, and renew it, in a way that others cannot. What are the aspects of the business model that competitors cannot easily duplicate or surpass?

Competitive advantages drive success if they are

• Differentiated: They are unique among competitors.

• Valuable: They provide some advantage to reaching and satisfying customers.

• Sustainable: They are durable over time and difficult to replicate.

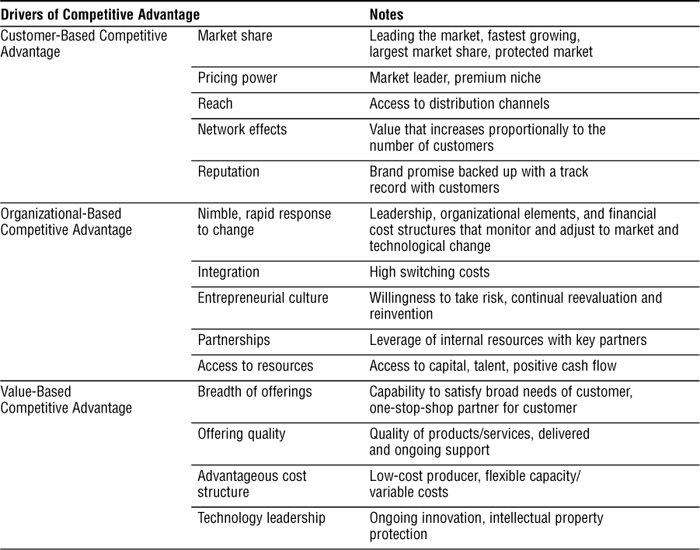

By analyzing and developing competitive advantages for a wide range of businesses, I have developed this distilled inventory of possible competitive advantages in Table 10.1.

Resources

What is needed to make the business model work? Resources are what are required to realize the value, including team, capital, partners, and time. A subtle yet important resource is opportunity cost—if this opportunity is pursued, what others will not be? The most significant of these can be the investment of the founders’ time.

Risk

Risk is about the chances of realizing the value coupled with the chances of wasting the resources. Known risks include the accuracy of the assumptions behind the model and execution risk in realizing the plan (sometimes referred to as unsystematic risk). Unknown risks are those risks associated with components of the model currently unforeseen, and externalities beyond the control of the business model, such as macroeconomic change (sometimes referred to as systemic risk).

Risk also implies what could be lost: investment capital, reputation, time, or future opportunity.

The hardest risk to evaluate can be in the biases of the founders. Because of this, the importance of using objective frameworks, such as those presented here, and having a set of candid mentors and advisors, is paramount. “Drinking your own Kool-Aid,” “falling in love with your own ideas”—the expressions abound that describe our difficulty in remaining objective when we have invested our entrepreneurial passion and energy. Most ideas fail, but none fails from lack of love from their champions.

The Business Model and Frameworks

As we move from idea to execution, it is important to express an opportunity in terms of the business model it supports. We are crossing the chasm from opportunity recognition to value creation. The business model is a framework for creating value from an idea, by building the idea into a system that considers all stakeholders’ needs. The business model, financial model, and business plan are closely related but distinct, and often confused and conflated. Using the car as an analogy, the business model is the engine, the financial model is the fuel or energy that makes the car go, and the business plan is the road or route on which you will drive (execute).1 It is essential to entrepreneurship and innovation to understand how the pieces come together in the engine to drive the idea forward.

The business model as the building block of innovation and entrepreneurship is increasing in importance in the collective conscience and literature. Not long ago, an organization would craft a business model and execute on the same model for decades. In today’s rapidly changing environments, the business model is viewed like a product line; it must be reviewed (and possibly reworked) frequently. This is in part driven by the diversity of possible successful business models in information-based economies, and experience-based economies. Information economies trade less tangible value, which can be packaged and delivered in ways decoupled from the restraints of the physical. This opens a wider range of possible business models. As James Gilmore and B. Joseph Pine describe in the book The Experience Economy, the evolution of economies has increased demand and opportunity for experienced-based and transformation-based businesses.2

Types of business offerings, in order of increased differentiation and the factors upon which they compete, include the following:

1. A commodity business charges for undifferentiated products. (Examples: oil, sugar.) Commodity businesses sell undifferentiated products and therefore must compete entirely on price.

2. A goods business charges for distinctive, tangible things. (Examples: shoes, televisions.) Goods businesses compete on the uniqueness of the value proposition in balance with price.

3. A service business charges for the activities you perform. (Examples: consulting, Internet access.) Service businesses compete on reliability and reputation of the offering.

4. An experience business charges for the feeling customers get by engaging it. (Examples: Starbucks, Disney theme parks.) Experience businesses compete on the brand promise of the experience.

5. A transformation business charges for the benefit customers (or “guests”) receive by spending time there. (Examples: vacations that teach skills, restaurants that educate about cooking/health, higher education institutions.) Transformation businesses deliver value that changes the customer beyond the delivering of the experience.

The more evolved stages allow more diversity in approaches, more innovation, and more creative business models.

Thought leaders such as Steve Blank have tied business models to the essence of entrepreneurship, stating, “A startup is an organization formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.”

Definition

There are many definitions of business models, but at the core a business model has three critical aspects: value creation, value delivery, and value capture. What value will be provided for customers and other stakeholders? How will the customer get that value? How will the business model capture that value for all the stakeholders involved? By value, we extend beyond financial gain, to include social entrepreneurship and societal, political, and organizational value.

The Business Model Canvas Framework

The Business Model Canvas (proposed by Alex Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur in their best-selling book Business Model Generation), depicted in Figure 10.3, has become the framework of choice for mapping out business models. Developed in an open-source format, with more than 450 experts’ input, it maps the key components of any business model.3

Part of its elegance is to lay out the entire model in a single view. All the major components important to a business model are defined and visible. The canvas breaks down the business model into nine components, which we cluster into these categories:

• Value Proposition (VP) (What you are offering)

• Customer Components (Who you are doing it for and with): Customer Segments (CS), Channels (CH), Customer Relationships (CR)

• Financial Components (What results you expect): Cost Structure (CS), Revenue Streams (RS)

• Resource Components (How you will do it): Key Partners (KP), Key Activities (KA), Key Resources (KR)

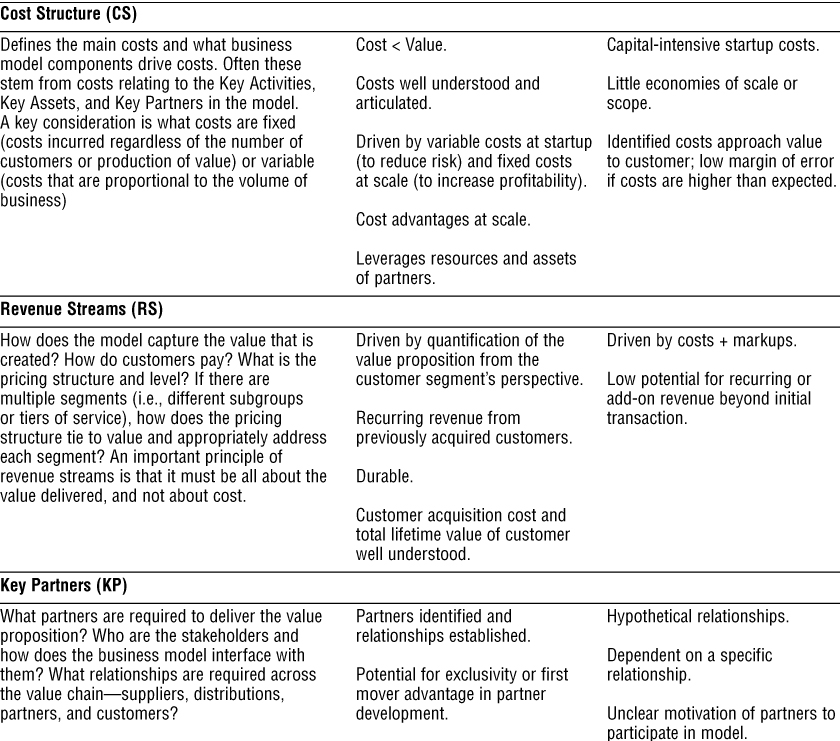

We use the canvas to map the opportunity across these components. Additionally, we use the canvas as a Screen, to determine strengths and gaps. Although the Business Model Canvas is most commonly used to map out and define an opportunity, it can be extended as an evaluation tool as shown in Table 10.2. With a business model defined on the canvas, we can evaluate the potential value of an opportunity by the nature of the canvas components using the following framework. The first column (“Map”) describes the components of the Business Model Canvas. “Screen” extends the canvas to evaluate the opportunity by components.

It is important to note that this framework addresses general truths. Plenty of successful business models might have characteristics that are identified as “Lower Potential” in this framework. “Lower Potential” components can mean more risk or complexity or difficulty in execution, but are not necessarily fatal flaws. In some cases, the same components of a business model that are complex or difficult to execute are transformed into competitive advantages in retrospect, because they are barriers to entry for new entrants trying to replicate the model.

“Lower Potential” aspects are inputs for opportunity shaping. How can the business model be recast or modified to address these gaps?

Assessing Strategic Context—SWOT

SWOT analysis—Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunity, and Threats—illustrated in Figure 10.4, is a straightforward framework for mapping opportunity. Pioneered at the Stanford Research Institute, it has been widely adopted and used for over 50 years. We have found it most useful to get specific about the major factors that influence an opportunity. Factors are categorized as originating internally or externally, and according to whether they are a positive or negative factor in evaluating the opportunity.

SWOT analysis is valuable because it is straightforward and concise. It provides a specific inventory of the major influences on an opportunity. It is less useful for measuring opportunities relative to one another or otherwise quantifying or evaluating.

Assessing the Essence of the Idea—TRIZ

TRIZ stands for the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving, an acronym based on its Russian language origin. It is a methodology and framework that identifies abstract patterns around specific problems and opportunities. It is very useful in the design and development of solutions.

Problems and solutions have underlying themes that are repeated across disciplines and application. Although there is a vast diversity of innovations, there are repeating patterns behind the specific solutions that form general rules of innovation. When you look at a specific problem and evaluate it in a TRIZ framework, the pattern of the problem points to a pattern of solution. The TRIZ process is visually depicted in Figure 10.5.

You start with the specific problem to be addressed, apply TRIZ principles in a generalized problem space, and then adapt generalized solutions back to specific solutions. TRIZ includes 40 inventive principles that are recurring patterns in innovation.4 For example, the principle of “Segmentation” is the general solution based on dividing an object into independent parts. The principle of “Universality” is the general solution of performing multiple functions with the same components (specific examples: a camera combined with a phone, or a child safety seat that converts to a stroller). An in-depth description of TRIZ is beyond the scope of this chapter, but it is a valuable framework to consider. It has the following strengths:

• It is more linear and methodical than the majority of brainstorming techniques, and can be more appealing to “left brain”-oriented thought.

• It cuts across disciplines, and is predicated on the assumption that solutions can come from other fields.

• It can stimulate new modes of thinking. With a finite number of patterns, each pattern can be considered in the context of the specific problem, in a search for solutions.

• It can be used to evaluate a specific opportunity or solution. Does the proposed opportunity follow an established TRIZ pattern? Do similar patterns offer insight into how the opportunity or solution can be refined or enhanced?

• It assumes a specific problem statement as a starting point, so it is philosophically different from problem-finding and exploratory approaches.

TRIZ is also useful in evaluating and reconciling performance trade-offs (“contradictions” in TRIZ terminology). These include technical contradictions such as engineering and business trade-offs (example: strength as beneficial, with a trade-off of added weight/cost). Also, this includes inherent contradictions such as trade-offs involving opposite requirements (example: desire for a comprehensive feature set, yet simple to use).

Assessing Internal Drivers—Organizational and Personal

How does an opportunity fit the founders and the founding organization? Ellen di Resta describes this well in Chapter 4, “Assessing Your Innovation Capability,” so we will not reiterate here.

Assessing and Addressing Risk—Discovery-Driven Planning

Discovery-driven planning5 is a way to think about and prioritize execution with scarce resources. Its elegance is in how it stages risk, and allocates resources based on risk reduction.

The key elements of the framework are to Map an opportunity in the following ways:

1. Start with the desired end state, mapping out what success would look like. Build an end-state financial statement for the business (revenue, profit, scale, etc.).

2. Make these financials flow out of a model of key assumptions; for example, the goal revenue built from assumptions about the number of customers, price points, and purchase volume.

3. Work backward through time from the end state to how to get there. If the end state is projected five years out, what assumptions are required to ramp to achieve those goals? The result at this point is a financial model of the business, and a set of the assumptions that drive the model.

4. Evaluate the reasonableness of assumptions against prior experience, business intelligence, and expert opinions. Tune the assumptions and model accordingly.

5. Now, look at the sensitivity of the model to the various assumptions. Do small changes in some assumptions have big impact on the end-state financials? What assumptions drive the model, and what is the risk associated with the accuracy of those assumptions? Are the key assumptions conservative or aggressive against benchmarks?

6. Based on this, develop a startup plan that spends time and resources to reduce uncertainty about those key assumptions. For example, if the most important driver that is least supported by data is product pricing, what early activities will increase confidence in pricing assumptions?

The shift in thinking in a discovery-driven way is subtle but the impact is profound. It has an inherent bias toward beginning with the end in mind, putting the goals and path to get there at the forefront. It also formally ties operations and operating assumptions directly to financial outcomes.

It is a road map for how to invest time and capital that optimize risk reduction, and therefore optimize return versus risk. Traditional approaches will allocate resources to sequentially build the business. In contrast, discovery-driven planning builds value by reducing uncertainty.

The model also provides ready feedback for progress. Revisiting assumptions as more information is learned directly ties to impact on the big picture.

Assessing Financials

Financial tools and evaluation is a field in itself, and detail is beyond the scope of the book. Briefly, expressing the business model in financial terms links the model, operating metrics, and financial outcomes together. Two critical measures flow out of the financial model:

1. Capital Requirements: Projections will show cash reserves/deficits over time. All startups will show a resource drain until a point where there is enough traction to generate positive cash flow (where sales exceeds costs). This point drives how much investment is needed, after which the business can pay its bills directly out of operations. More colorfully put, “Happiness is a positive cash flow.”

2. Valuation: Projections can also be used to estimate what the venture is worth now and in the future. Comparing financials measures (for example, revenue, profit, growth) to comparable established businesses provides a view on future value. Net Present Value and similar analyses can provide a view on the current value of the idea, factoring in future sales projections, the resources required to get there, and the risk along the way.

Investopedia (www.investopedia.com) is a great starting point for financial terms and tools.

Assessing Innovation—The Innovation Bull’s-Eye

For innovation to be realized, three core elements must come together. An idea must be desirable, feasible, and valuable: desirable in that it fulfills a need and fits into a person’s life; feasible in that the solution can be realized from a practical and technical standpoint; valuable in that there is a business model and path to adoption. These come together at the Innovation Bull’s-Eye.

These characteristics are derived from the major disciplines in the Kanbar College DEC curriculum—Design, Engineering and Commerce (Business)—a curriculum built around innovation. Design can improve the world by helping find problems and model solutions that improve the ways specific groups of people interact with each other and the world around them. Engineering can improve the world by using the rigors of mathematics, science, and simulation to solve the complex problems that occur when these solutions are integrated into actual products and processes. Business can improve the world through strategies for capturing the economic, social, or environmental value generated by interactions between these solutions and the people who benefit from them.

Design is where innovation intersects with people and identifies what is usable and desirable. The scope of design has evolved beyond objects and products to more broadly include the process of conceiving, planning, and modeling what might be possible.

What design and the design process bring to innovation:

• The ability to find opportunities for positive change

• The process of evaluating and responding to context and imagining something different

• A way to be empathetic, to view the world through the eyes of others, and to thoughtfully analyze what they see

• The role of inquiry in problem finding and framing

Design is a means of not only solving problems, but also finding opportunities to solve the right problems for particular groups of people.

Engineering is where innovation intersects with technology and identifies what is feasible and attainable. At the highest level, engineering can be viewed as the overlap of scientific knowledge with societal need.

What engineering brings to innovation:

• Rigorous problem-solving and troubleshooting skills

• An understanding of systems dynamics and rigor in systems thinking

• The ability to identify what can be developed and how

• An ability to evaluate trade-offs of benefits versus cost and form versus function

The engineering perspective not only is a means of solving problems with technology, but also is about the possible, and finding new opportunities that are enabled by new technologies.

Business is where innovation intersects business to create value and identify what is valuable. It is the process that connects the needs of people to the systems, objects, products, or services to fulfill these needs.

What business contributes to innovation:

• A way to identify and frame new business opportunity

• A way to understand how an innovation can scale to have broad reach and impact

• The ability to plan and marshal resources to execute a project/business/innovation

• A way to understand the delivery of innovation in terms of the fit with existing social systems, delivery mechanisms, and channels

• The perspective of value creation and its qualitative and quantitative impacts

The business perspective is not only a means of commercializing innovations, but also a means for finding new opportunities to create value.

We can use this innovation framework as a lens to evaluate and shape specific opportunity. To this end, we take the innovation ideal of the intersection of all of these dimensions as the Innovation Bull’s-Eye, and deconstruct each element as depicted in Figure 10.6 and Table 10.3.

Ideas with high innovation potential will simultaneously be desirable to users, feasible to create and deliver, and valuable to all.

Screening Matrix Frameworks

These frameworks can be viewed as screening matrices. We map the opportunity against each framework components, and how well an opportunity stacks up against those factors. We evaluate a specific opportunity against an ideal, and also to screen a portfolio of ideas to rank those that should get more resources. We use them to screen results of brainstorming, and as parts of a stage gate process for development pipelines. Different screening matrices serve different stakeholders. As entrepreneurs, we can use a screen that fits our personal criteria to evaluate where to put our energy. As inventors, we can use a screen that matches ideas against customers’ needs and pain points to evaluate their merit. As investors, we use screens that match investment criteria against companies seeking capital.

Scoring with Matrices

For those who seek more quantitative approaches (guilty by confession), matrixes can be extended to score an opportunity against an ideal, or rank it against others. For each component of the matrix, a score can be assigned for that component based on how well the specific opportunity fits the criteria of that component. Adding up all the component scores provides a numerical measure of the opportunity against the ideal, and provides a holistic summation of the idea.

Shaping: Rinse, Lather, Repeat

Recommendations: A recurring theme of this book is iteration. Although many of these frameworks are meant to evaluate opportunity, that is the beginning not the end. Use the gaps—the areas where an opportunity does not measure well against a criteria—as stimulus for iteration, refinement, and new ideas built on the old. Although the frameworks highlight why a particular solution might fall short, they are also guideposts that say if these gaps can be addressed, there is real opportunity to be realized and value created.

Endnotes

1. Credit my colleague Heather McGowan for this helpful analogy.

2. For more information refer to The Experience Economy, Pine and Gilmore (1999).

3. Business Model Canvas, www.BusinessModelGeneration.com.

4. Tate and Domb, “40 Inventive Principles with Examples,” TRIZ Journal, 1997.

5. Discovery-driven planning was developed by Rita Gunther McGrath and Ian C. MacMillan.