12. Business Model Execution—Navigating with the Pivot

David Charron is currently a Senior Fellow and Lecturer in Entrepreneurship at the Haas School of Business, teaching courses in the MBA, EWMBA, and executive programs. He is Berkeley’s faculty lead on the NSF ICorps program. He has served as Executive Director of Lester Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation and the Berkeley Innovative Leader Development effort. He is an entrepreneur, an investor, a mentor, and a consultant in the Silicon Valley and has 25 years of focus on technology commercialization and entrepreneurship with Stanford, MIT, and Xerox PARC, among others. He frequently travels internationally as a professional educator and business consultant. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Stanford and an M.B.A. from Berkeley.

If you’ve ever made a significant change in a business, you have a gut understanding for the word pivot. Pivoting is a term widely used in the entrepreneurial community to describe changes in the assumptions underlying a business model (proposed or established). Managers at all levels need to understand why and when pivots happen, and how they can better lead the pivoting process. Effective management of a business pivot requires skills in both design and learning that are often overlooked in the early phases of a business.

New ventures often enter markets without established business models and use techniques to find opportunities where enough customers are willing to pay for the solutions the company will create to “build a business.” These processes have been popularized through the work of Osterwalder and Pigneur’s Business Model Canvas, Steven Blank’s Customer Development process, and Manifesto and Eric Ries’s Lean Startup movement. These works represent a business description framework, a process for defining opportunities, and an ethic around efficient use of capital that have substantially shifted the entrepreneurial value creation process.

Pivots have come to represent the mythic capability of entrepreneurs to apply science to the entrepreneurial process. Rigorous testing guides them to alter their business models to exploit the largest and most profitable models quicker than their competitor. I view pivots as a management capability to combine learning and design to flexibly and nimbly adapt to the changing landscape that any organization encounters as it moves through a market landscape. Stories of pivots are told often in hindsight and in a manner that makes the pivot appear seamless and planned when they likely were not.

Different but Dependent Processes: Entrepreneurship and Innovation

Disrupt Together brings together two different disciplines, innovation and entrepreneurship, in recognition that disruption is based in both the new ideas and the capability of those ideas to scale repeatedly in markets. The disciplines are linked, but different in several fundamental ways. One important way to describe the differences in the disciplines is to view them as temporal cycles. Innovation cycles tend to be within a short time frame (hours, days, or weeks of effort), whereas entrepreneurial processes tend to be longer (years to many years) efforts.

Innovation processes typically use a framework that starts with problem finding followed by problem solving. The process continues cycling iteratively, testing potential solutions against a framed understanding of need until a match between the solution and an express need is found. The innovation process is a highly general process that can be used to systematically approach just about any problem.

Entrepreneurship is about using innovation processes to find a business model that can achieve economies of scale and scope. The entrepreneurial team uses innovation processes across all the elements of a hypothetical business model canvas—finding specific problems and then looking for specific solutions. Customer Discovery techniques put the customer and value proposition first in line to be solved before the other elements in the business model can be resolved. This is called the search phase, when the entrepreneur seeks to validate the business model before executing against it. The execution phase in entrepreneurship follows the search phase and is operational in nature, exploiting the found business model.

Whereas the innovation process is applicable across many situations, the entrepreneurial process is a highly specific technique used in business to create and grow successful organizations that create value through scale and scope.

These processes are different but dependent. Entrepreneurship needs innovation both as the seed of its effort and as a business process that constantly drives new inputs as the company grows toward greater scalability and repeatability. These innovations often cause a company to pivot, or alter its business model.

What Is a Pivot?

This chapter recognizes two distinct phases in an effort to bring an innovation to market through either a new venture or a corporate effort: the search phase and the execution phase. All efforts start with a search phase in which the new venture seeks to establish a business model and transition to the execution phase. In the search phase, pivots occur when a hypothesis regarding an element of a business model either is invalidated and replaced with a new hypothesis, or is proven to be true. During the search phase, pivots can occur rapidly. Investment in a particular model has not yet occurred and the cost of pivoting is very low.

The Business Model Canvas is the commonly used framework for exploring new business opportunities regardless of phase (see Figure 12.1). In the search phase, entrepreneurs populate the canvas with hypotheses about how each element could work.

They start on the right-hand section of the Business Model Canvas called Customer Segments. These segments or target customers are easy to define and validate through testing. Although they’re seemingly easy to define, many search-phase companies pivot quickly around their customer segments. In practice it seems that this is the most difficult section for new entrants to define and evaluate. This difficulty might stem from the entrant having limited knowledge of the opportunity chosen. Entrepreneurs are limited by their direct experience and can make mistakes in interpreting the signals from the customer. They are forced into a learning mode to better understand the critical aspects of their customers and markets.

Many search-phase companies fail to define a target market of a reasonably homogenous set of customers who will express loyalty to the product idea. Loyalty in its first set of customers allows a company to more favorably set its pricing, value creation processes, and resource acquisition plans.

After the target market is set, the company must turn its attention to its product configuration. The goal here is to obtain product-market fit, a concept measured by steep reductions in the customer acquisition cost and increasing demand. The company is still in search phase here, validating its value propositions, relationships, distribution, and possible revenue models. Hypotheses are generated and tested quickly, with as little capital consumed as possible. The hypothesis generation and testing begins to extend to the left side of the canvas and to costs also in anticipation of possible product-market-fit.

If the members of management of the search-phase company bring anything with them into the execution phase of the business, it is the flexibility of mind that comes from making multiple, albeit inexpensive, pivots. It is often the lack of ability to pivot, not the pivot count, that indicates the potential decline of a company. Management should have learned the process of pivoting and accumulated the know-how about why the opportunity does or doesn’t work.

The transition from search to execution phase as depicted in Figure 12.2 happens as demand for its product increases and the company begins to scale its internal processes. The business model has become established (it doesn’t have to be correct) and the company begins to execute against the model. For such an execution phase company, a pivot now becomes any intentional and significant change in the operational business model of the organization. Significant means a reconfiguration or redirection of the assets and operations of the company. Pivots are designed to improve the performance and expected outcome of the company.

For the majority of this chapter, I will focus on pivoting in execution phase companies.

In either the search or the execution phase, pivoting can be thought of as a form of innovation process. When it’s done correctly, management tests assumptions, learns about requirements, finds problems, and then experiments with new solutions. Those solutions that work survive and are implemented.

Why Pivot?

Each day the management of a new venture must decide to continue to rely on hypotheses underlying the business or to refocus on a new set of hypotheses. The Persevere, pivot, or perish decision frame is front and center daily for start-ups.

The decision to persevere, or continue the operations of the company as they were the day or week before, is often the default for management and is based on hypotheses created when the operating model of the company was chosen. Those hypotheses span the business model from revenue and costs to partnerships and asset creation. New information generated by the activities of the company should be used to continuously test those underlying hypotheses. Does the information generated invalidate a hypothesis and cause a need to improve the business model? Does it generate a need to pivot?

If an operating assumption is disproved, an alternative must be chosen to replace the now-defunct part of the model. At the heart of creating the new model is a problem-solving innovation process in which management creates several alternatives that can substitute for the disproven hypothesis and then tests them in the market and against one another. Only when the best alternative is discovered does the company pivot its business model.

If the company discovers a better opportunity than the one currently pursued by the company, a pivot should also be considered. Management considers the risk/reward trade-off of persevering compared to pivoting to the new model. Only when the risk is small and the reward large in comparison to risk/reward of persevering is the pivoting warranted.

Even a casual reconsideration of a business model can create many opportunities to pivot. Pivoting based on data that is not relevant to the current business or that is of low quality or quantity can lead to mistakes and wandering through business models. Pivoting based on the creation of a single alternative to the current business model generates the potential of jumping from one model to another, wandering through a series of costly pivots.

The best pivots occur when the team creates an open learning environment and carefully considers the quality and quantity of new information driving their design process. The team is allowed to define several alternative hypotheses and business models that can be compared to each other in their ability to solve problems and generate larger opportunities. They can filter through opportunities quickly looking for advantages in both market entry and long-term sustainability.

Companies pivot in response to opportunities to make the business perform better.

How to Pivot

When management decides that the business must change its business model, speedy but careful modification must occur. Changes in the model have impact on the market’s perceived position of the company and the company’s employees. Leadership should be able to integrate its understanding of the market environment (learning) and its value-creation strategy (design) and clearly bring its employees, managers, and board into alignment around any pivot.

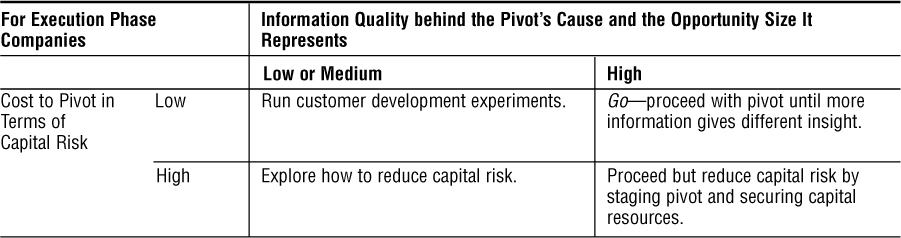

Table 12.1 is a guide for execution phase companies to help them determine how to approach pivoting the company.

There is one other type of pivot: the bet the company pivot. This kind of pivot arises when the company is doing so poorly in its execution that it must redefine itself. These pivots tend to be more like a company restart, when the entire business model is changed in an attempt to save the company.

If your company is in the search phase, your business model is filled with untested hypotheses and the operations of the company are focused on finding information to validate or invalidate the hypotheses. Your goal is to move from search to the execution phase by filling in your business model with assertions supported by field data gathered through customer development and validation. If an assumption behind the proposed business model is wrong, it is replaced with a new hypothesis, and the testing continues. The cost of a pivot is very low and is primarily the time invested to develop quality data.

Resource acquisition is a critical step in the pivoting process. Ample funding and key resources are critical before, during, and after the pivot. The Lean Startup movement teaches a mechanism that is applicable to all companies: Do not overspend on activities for which the outcome is based on risky hypothetical outcomes. In the case of both Magoosh and Uber, cash resources were available from sales and from investors. Deploying that capital for the purposes of the pivot was the responsibility of the CEO. Both acquired the key resources and shifted operations appropriately to the new models given their appetite for risk. Magoosh did the pivot more concertedly and Uber more aggressively.

When Pivots Don’t Happen

Failure is a high-percentage bet for most efforts to bring new products and services to the market. If pivoting is a skill or technique that can be taught, why don’t most efforts work themselves into a position of success through pivoting? Is the lack of pivoting the cause of failure?

Pivoting is about having options and the ability to pursue those options. Certainly an energy production company pivoting to become a software producer might be nearly impossible. But a company of talented individuals moving from one market focus to a better market seems easy—except that the cognitive struggles of the entrepreneur, their advisors, and the board often get in the way. The Hypothesis-driven entrepreneurship movement is an attempt to bring rationality to start-up decision making. If only it were that easy.

Those who take on risk often suffer from one or more cognitive biases that skew the decision-making process:

• Overconfidence: Entrepreneurs enter into a new venture confident of their own skills, product vision, and customer understanding. Overconfidence is a cognitive bias in which the individual holds strong beliefs without regard to information that is available or that could be developed that might disprove the original assumption or the cause of the belief.

• Escalation of commitment: This is related to overconfidence because overconfidence can drive an escalation of commitment, but there is another more insidious part. Loss aversion is a cognitive bias in which people strongly prefer avoiding losses in favor of gains. This causes innovators, when faced with a pivot, to ascribe undue risk of loss in pivoting and undue gain to staying the course.

• Inability to see new opportunity: This is a framing effect bias in which information about a new opportunity is readily available but the individual cannot reach a conclusion to pivot. We all bring our own specific experience to new information, and our experience limits and shapes our ability to see and comprehend new data and scenarios. Investors know this bias well—they see it in their CEOs quite frequently. When they see it, the question turns to pivoting the CEO either by strength of argument or by positional authority.

• Inability to pursue the pivot: Pivoting costs money and can create dislocations in the operations of the company. Employees might be let go and new employees hired with different skills. Investment capital might be required to acquire new customers, create new product lines, and scale the business. Even though the new pivot might save the company, exploit a larger opportunity, or provide a greater financial return, there is no guarantee that the quality and quantity of resources required will be available to successfully pivot.

We all carry those cognitive biases, along with many others, and they inform and shape our behaviors. Pivoting a business is the responsibility of the CEO—the one person the team and board has trusted with decision-making authority. But even in the case in which the CEO chooses to pivot the company, the company must follow to ensure the success of the pivot. So lastly, the CEO must have significant leadership skills to motivate and convince others that the new direction, at least at the moment, is the best opportunity and should be pursued with alacrity.

Summary

Pivoting a company requires the confluence of an opportunity and the skill and resources to execute. An innovator’s ability to pivot, their flexibility of mind and skill, is a key success factor in today’s world of market entry. No markets remain constant over time, and opportunities that appear today might fall out of favor over time. Innovators must embrace the concept of pivoting, and must understand why pivots occur, how to change an organization to execute a pivot, and finally the challenges we all have that limit our ability to realize value when a potential pivot arises.

Pivoting is also an innovation process that requires a disciplined process to avoid being misled and executing well against newfound opportunities. Innovation processes have costs that can be modeled and applied to return-on-investment metrics. Innovation and pivoting are management techniques that organizations should embrace and embed into their culture to foster agility and openness.