Chapter 15

Great Expectations

In This Chapter

- Identifying problems

- Solving true causes of problems

- Getting better by operating differently

- Trying new ways

“You’re only as good as your last . . .” Finish the sentence. Everyone—inside your organization, as well as your customers—wants to know, “What have you done for me lately?”

Harvey MacKay, businessman and author, says that gratitude is the least deeply felt emotion. (Think about that one!)

The good things you’ve done for customers in the past counts for little if you can’t help them today—now. (Sometimes, don’t those customers just seem like selfish ingrates!)

With just about every company trying to distinguish itself by its service, customers are getting spoiled. They’re often getting good service, so they know what it is and expect nothing less.

Get Better or Get Out of the Game

To keep pace with what your customers expect—what they’ve been taught to expect by really good service organizations—you’ve just got to keep refining how you do things. It’s improve or perish.

The call to arms in many companies is this rallying cry:

“Continuous Improvement!”

The fundamental way to improve your service to customers is by bettering your operation. And there are two ways to do that.

- Solve internal problems that stand in the way of delivering great service.

- Deliver improved services externally by working better internally.

This chapter helps you do both.

Probable Cause

In earlier chapters, we talked about solving your customers’ problems. That’s removing the speck in your customer’s eye. Here, we’re going to talk about getting rid of the roadblocks to progress in your own organization. That’s taking the logs out of your company’s eye. As Don is fond of saying, you can’t create service breakthroughs until you stop service breakdowns.

Let’s say you know things aren’t going right. Product returns are up. Complaints are up. Sales are not.

Word to the Wise

The true source of a problem is its root cause. The problem itself is often only a visible sign—a symptom—of the true cause of what’s causing what’s wrong.

If your company is like most, the instinct that seizes everyone when problems undeniably surface is to start pointing fingers. Everywhere. Like crazy.

Customers complain to customer service. Customer service blames your sales people for over-promising. Sales points the finger at manufacturing for building inadequate products. Manufacturing points the finger at marketing for inadequate product specifications, and at suppliers for unreliable material. Suppliers point the finger back at the company for forcing costs down to unreasonable levels. Round and round it goes.

Look, blame doesn’t solve problems. Neither does attacking problems without identifying their root cause.

For example, at home your partner closes the refrigerator door and a picture hanging on the wall comes crashing down. Obvious cause? Your partner slammed the door too hard. But the true root cause is more likely a picture that was hung on a screw that wasn’t adequately fastened into the wall. (And the cause of that may be at the heart of this particular problem, and probably some others . . .)

Watch It!

Beware the Fire Drill mentality. When things go wrong, what do you concentrate on? Fixing the problems at hand or going beyond that to find out what the cause is to avoid future problems? Too many companies today are stuck in the vicious cycle of putting out fires, and creating more fires by not tending to problem prevention because they’re too busy putting out fires. If you find and attack the root of your problems, the number of fires you need to extinguish will be drastically reduced.

Digging to the Root

How can you avoid the blame game and get to the root cause of problems to really fix what’s wrong?

We’re going to show you a simple method for problem identification. But first, a couple of important points:

- Problems are rarely caused by one single factor. In this complex world, everything is part of an interrelated, interdependent system. A problem is a puzzle with more than one piece.

- Identifying and solving problems works best when many people—from many different parts of the company—have input into the problem identification process.

Here’s a simple method that can help you identify many possible causes of problems. Create a Cause and Effect Diagram. This tool, developed by Japanese quality expert Kaoru Ishikawa, was created to support Total Quality Management efforts in manufacturing. It’s just as applicable to service issues.

A Cause and Effect Diagram, or fish bone diagram, can identify many different possible causes of a problem.

Look at the diagram. Notice how it looks like the skeleton of a fish? That’s why many people refer to this tool as a fish bone diagram.

Watch It!

Money can be at the root of your problems. A cash-starved operation simply can’t make the investments necessary to run the business as it should be run. Don’t fall into the trap of blaming a lack of funds for all your troubles. That prevents you from seeing other, more likely causes, and blocks innovative thinking for solutions that may have little to do with funding. And, we should note, a company with too much cash can have real problems as well. It can get sloppy—drunk with success— spending foolishly and believing it absolutely knows what customers want. (Now there’s an evil.)

Creating a Cause and Effect Diagram is extremely easy. Look again at the diagram. See the head of the fish? That’s where you state the symptom of the problem (or effect). For example, increasing returns, high number of repair calls, decreasing sales, whatever.

Now look at the major branches. See the label at the end? These are the major categories of likely problem-causers. Most every problem has its root cause in one or more of the following areas:

- Machine. Wrong tools for the job; unreliable tools; out-of-date tools. These factors can be behind the detectable problem.

- Method. Is it how you’re doing things that’s creating or contributing to the situation?

- Materials. “Garbage in, garbage out.” You can’t make products better than their components. Faulty parts make for faulty products which make for service nightmares (repair orders, replacement or refund requests . . .).

- Measurement. Do your surveys tell you the vast majority of your customers are absolutely delighted, while they’re absolutely abandoning your product? Maybe they really aren’t so delighted. Double-check your attitudometer.

![[image]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/detail/detail2/0028619536/0028619536__the-complete-idiots__0028619536__Images__extra_watchit.jpg) Watch It!

Watch It!

Tempted to blame “pilot error” people problems for your troubles? This should be your last “likely cause.” Often, good people perform poorly because the system they work within prevents them from doing better work. Thoroughly scrutinize the system before looking at individuals; you’ll likely find your true cause there. - Money. No mon’, no fun. Inadequate cash flow can starve an otherwise healthy operation, delaying necessary hiring, postponing purchasing computers or phone systems, and so on.

- Man. (Okay, people—to be politically correct—but we’ll use Man to keep our alliterative MMMMMM scheme going.) Inadequate staffing can cause problems; so can over-staffing and incompetent staffing.

- Market Forces. We mean the external environment: forces such as competitive actions, social changes, political, and economic trends.

Putting Meat on the Fish Bone

Here’s a simple 10-step process for using the fish bone diagram to identify possible sources of your challenges:

- Identify the problem you want to solve.

- Put the problem description at the head of the fish.

- Gather your colleagues and have a free-flowing idea generating session about possible causes.

- Identify as many possible causes as possible. Encourage creativity; don’t debate the merits of any suggestion—you’re simply listing possibilities.

- Group related ideas together under the major headings along the big branches.

![[image]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/business/1/0028619536/0028619536__the-complete-idiots__0028619536__Images__extra_service.jpg) At Your Service

At Your Service

Idea generating sessions (brain-storming, some call it) are most productive when there’s a wide variety of perspective. Invite people from around your company, perhaps some vendors and even customers, to help you see beyond your own (and your department’s) limited line of sight. - After filling up the diagram, step back and review what you’ve come up with.

- Ask the group for their ideas on what, from all the possibilities you see before you, are likely causes.

- Explore likely causes further. Take a branch of the fish bone, for example, machinery, and create another fish bone diagram for it. The major branches of a fish bone for a suspected machinery problem might be labeled Maintenance, Parts, Methods, and so on.

- Gather and analyze quantifiable data related to the leading suspected root causes. Verify (or invalidate) your gut instincts.

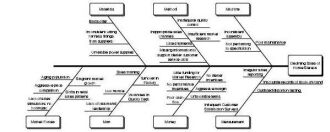

- Draw conclusions and take action after knowing what the root causes are. This particular cause and effect diagram lists many possible causes in several areas for declining sales of a stereo manufacturer.

Watch It!

Cause and effect diagrams can tell you which way the wind is blowing, but they cannot tell you the speed of the wind or the air temperature. In other words, you need data to complete the picture. Even if a whole room full of wellinformed people review a cause and effect diagram and agree that Factor X is the culprit, they might all be wrong. A consensus gut feel is still only a gut feel. Complete the picture with hard data.

The sample diagram shows how a completed fish bone diagram looks. This particular cause and effect diagram lists many possible causes in several areas for declining sales of a stereo manufacturer.

Here’s a simple process to help clarify your thinking about problem causation. Ask the following questions:

- Where are we now in performance?

- Where do we want to be?

- What do we think is keeping us behind?

- What do we know so definitively we can prove it?

- What do we need to find out?

- Where can we get the additional information?

- What will we do with the information once we have it?

- What do we need to do to fix the problem?

- Who’s responsible for implementing changes?

- What’s the timetable?

- How will we monitor progress?

The 5+/20+ Method

Identifying the possible cause of a problem may help you see the surface of the problem more clearly. But to really solve the problem will require you to get beneath the surface.

We’ve combined a couple of classic problem-solving methods into a process we call the five-plus-twenty-plus method. It’s a two-stage process.

- Take any problem and ask why it occurred. Take the answer to that question and ask why, and so on for at least five levels of detail.

- When you’ve gone at least five levels down, and truly believe that you can go no further, begin listing possible solutions to this root cause. List at least 20 possible solutions.

Here is an example problem:

- You can’t handle all the customer calls coming into the company. Why?

- Your company is receiving more calls than expected from customers. Why?

- Customers are asking questions about your new Widget 2000 model. Why?

- Customers don’t understand many of its features. Why?

- The features seem to confuse customers. Why?

- The ones on the new model work differently than most in the industry. Why?

Watch It!

Don’t look for the right answer to what ails your firm. There’s no right answer. There are many, many possible solutions to any challenge your organization faces. And some of the best may be the least obvious. Solving real world business problems isn’t like completing a grade school fill-in-the-blank exercise.

We thought we knew what customers wanted.

Bingo!

Actually, this line of analysis could go on for a few more levels. Once you get to the root causes—and there probably are a few here, list at least twenty possible solutions.

Notice how much different this list of twenty solutions to the root cause is from what it might have been had you just stopped at the first or second why. And notice how much more intriguing your solutions are once you get past the most obvious two or three.

If you don’t solve for the root cause of the problem, you’re not solving the problem.

Progress Through Process

How you do what you do is as important as what you do. In other words, turning the nut on a bolt with your teeth probably isn’t as good a method as using a fitted wrench. Both turn the nut. So both do the job. One does it much more efficiently (not to mention painlessly).

Analyzing Work

Could you speed up the service you provide your customers? Could you trim costs by working more efficiently? What if you eliminated unnecessary repetition, delays, approvals, and the bureaucratic steps you have to take to check an order, confirm pricing, review an invoice, answer a technical question, or whatever you do to assist customers?

At Your Service

When examining your work processes, think macro, not micro. Most work processes include many steps to completing a task or achieving an objective. Rarely do all those steps fall within one work group or department, or report to the same top manager. So think across the organization, and beyond your organization. Picture the whole, not just the part(s) you know best.

We have yet to meet anyone working in any company of any size that could honestly say they could not possibly improve their work processes.

Here’s how you can begin to analyze your work-flow to seek ways of improving it.

Identify the actual steps in a specific process. Focus on individual work steps—not departments, not jobs, not people.

Be very specific. It’s not, “give service on the telephone.” It’s:

- Answer the call.

- Greet customer.

- Determine the nature of the inquiry.

- Query the database for applicable information.

- Provide appropriate answers.

- Ask the customer if there is anything else they need.

- Respond appropriately: Query the database again, or, if necessary, transfer the call, or, ask the customer if she can hold while information is sought; if yes, proceed to obtain information from the sub-system or internal information source; if no, schedule a follow-up call with the customer.

- Thank the customer for calling.

- Wait for the customer to disconnect.

- Disconnect the call.

- Input the service call and results into the database.

- Complete any pending information gathering, and so on.

Draw a map of the process, showing each individual step. There’s a standard set of symbols for illustrating work-flow (which you can find in many graphics software packages) but don’t worry so much about following the “proper” protocol for the map. Devote your energy to identifying the exact steps in the process. If you understand your map and can explain it to other people, it’s probably fine for your purposes.

At Your Service

Evaluating processes has evolved to a fine science, with very sophisticated software—and consultants—available to undertake “business process reengineering,” known as BPR. Your own company may have people knowledgeable about BPR available to help you redesign your work. You can usually find them in either the finance or information technology departments. Or, if you work for a small company with limited resources, consider doing the analysis yourself or retaining a consultant to help you.

Verify the steps in the process. “Attach” yourself to the work. Walk through it every step of the way, as though you were the question being addressed or the paper or work being handled. Be sure you didn’t overlook any steps along the way. If you did, add them to your map.

Ask the following questions:

- Why do we do it this way?

- What if we didn’t do this step at all? Who would notice? What would happen? What’s the risk involved?

- How could we achieve the same objective (assuming its worth doing), by doing it a different way? How many different ways can we think of to do it?

Discuss with your colleagues across the organization ways to streamline your processes. Create plans for alternative methods. Select a new method. Test the new method—on a small scale—before changing the whole operation. Identify and work-out the kinks before turning your company—and your customers—on their heads.

When you begin examining business processes with a macro view, some colleagues may feel threatened. After all, you’re looking over their “turf.” Likewise, in the process of improving processes, you may find ways to eliminate unnecessary work—and the jobs that do them. While process improvement is vitally important to the quality of the service you provide to your customers and the fiscal health of your company, some of your colleagues may resist the effort. You’re more likely to succeed when your effort has the enthusiastic support of top management.

Growing Pains

Change can be painful, but you can’t grow or get better without changing. Asking people to change their ways—even to solve a problem everyone agrees exists and is undesirable, can be uncomfortable to some.

Quote, Unquote

Change isn’t made without inconvenience, even from worse to better.

—Richard Hooker, sixteenth century English theologian

Your best strategy is to acknowledge people’s very real, very genuine discomfort. Explain how changing things delivers a benefit to your company and your customers. Ask people to join you in that common goal.

Treat everyone fairly in the process. Keep them informed of your objectives and methods. Try to generate excitement for the better future that you imagine.

Nonstop Improvement

Some people are never satisfied. Hope they work at your company. There’s always room for improvement; always a better way.

Should you spend your time fine-tuning an existing process or looking for ways to replace it?

Seriously, when you make it a way of life to constantly question the way your firm does things, you’ll develop a sense for when you need to fine-tune and when you need to overhaul. The key is to keep fine-tuning until you overhaul.

Quote, Unquote

Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.

—Samuel Beckett

Failure: Always Better

You can’t get better doing what you know already works. You have to experiment. Try some things.

The more new things you try, the more likely you’re going to have some clunkers. Not everything works.

And if it does, you’re probably not reaching far enough. In baseball, they say, you can’t steal second base with a foot on first.

New things you try that don’t work aren’t failures. They’re learning experiences.

Quote, Unquote

There’s only one corner of the universe you can be certain of improving, and that’s your own self.

—Aldous Huxley

The Ultimate Improvement

Take a look in the mirror. You’re staring at your best bet for improving your operation and your service to customers.

The degree of improvement you can influence depends on how much better you are—personally—at understanding what customers value, and at imagining how your business can provide that value—and how to do it as efficiently and effectively as possible.

The Least You Need to Know

- Your customers expect you to keep getting better.

- To get better you first need to eliminate your problems.

- Problems can be eliminated only when you get to their root causes, perhaps by using a Cause and Effect diagram and other analytic methods.

- Improving your work requires a commitment to continuous improvement and a macro view beyond your micro area of work responsibilities.

- Improvement is an ongoing process that requires thorough analysis and innovative experimentation.