Creating More Accurate Acquisition Valuations

In “hot” deal markets, executives often overvalue companies they are considering acquiring — and conversely undervalue potential acquisition targets when the economy is weak. Fortunately, there are steps managers can take to adjust deal valuations for these common biases.

Managers often must make decisions about complex strategic issues, and they are expected to make choices carefully and objectively. A private equity fund manager, for example, may have to decide whether to bid more in a highly competitive auction. A retailer may want to figure out whether to make an acquisition at a time when prices are at or near the top of the cycle. In a different vein, an auto company may want to determine how long to hold onto a money-losing plant as the economy sinks into a recession. Such examples speak to an interesting dilemma: In boom times, deals are often in demand and expensive (and acquirers tend to know it), but when the economy cools off, acquisitions fall out of favor and prices decline.

The psychology of judgment and decision making predicts that the way executives frame their deals partly determines their acquisition choices under uncertainty.1 On the one hand, investor exuberance, the positive sentiments of boards and the willingness of rival managers to invest at higher levels can cause executives in “hot” deal markets to view acquisition opportunities as more attractive than they actually are. On the other hand, cognitive biases — such as loss aversion and a narrow perspective that does not consider long-term growth options — subdue companies’ acquisition behavior during “cold” markets.2

A biased valuation analysis is worse than useless, so this article is designed to improve the use of valuation methods in a way that can help mitigate decision biases. (See “About the Research.”) Because it is difficult for executives to recognize their biases and make adjustments, we suggest they do something that should be much easier: Use a formalized process to de-bias the decision-making team. The initial step is determining whether you are facing an investment in a “hot” or “cold” deal market, something that can be revealed by the number of deals.3 Subsequently, we propose taking a broader view, supported by sanity checklists for predictable valuation biases and illustrated with cases. In “hot” markets, having a valuation checklist can help executives temper their natural inclination to focus on growth options and refocus it on staging, deferring or recouping their investments. Similarly, in “cold” deal markets, a valuation checklist can help executives divert their natural attention from short-term risk to long-term growth options.

About the Research

This research draws on the marriage of behavioral economics and corporate finance to develop ways of improving acquisition decision making under uncertainty. In the field of behavioral economics, we conducted experimental and archival research. The work implies that acquisition strategy is vulnerable to the way managers perceive risk and losses, judgment biases in their strategy, the bidding behavior of rivals and mispricing in financial markets. In the field of corporate finance, the existing toolkit for company valuation (discounted cash flow) falls short in guarding against such biases under uncertainty.

In the past decade, we employed methods that extend valuation models to better deal with uncertainties. Conducting valuation analyses in private equity, mining and telecommunications, we observed that experienced acquirers do better when they take a broader view rather than when they consider deals in isolation. They intuitively deal with biases when they consider uncertainty and path dependencies inherent in startup ventures or serial buy-and-build strategies. Such investors opportunistically use uncertainty to their advantage.

The marriage of behavioral economics and company valuation is further developed in Han Smit’s forthcoming book, with Thras Moraitis, Playing at Acquisitions: Behavioral Option Games.i

Not All Acquisitions Are Go/No-Go Decisions

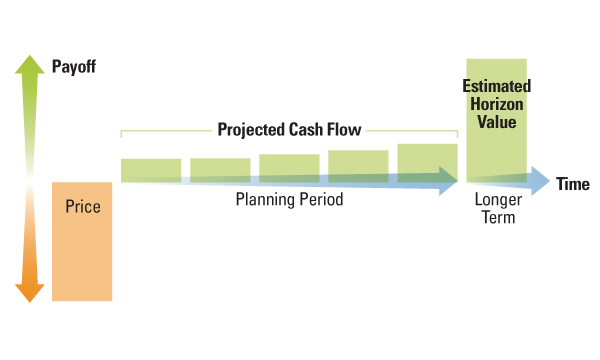

Conventional capital budgeting methods — including discounted cash flow and net present value analysis — suggest that businesses should execute deals as soon as the net present value becomes positive. A company’s value is usually based on the value expected to be generated by the transaction during the estimation or planning period, and the anticipated value down the road, often called the horizon value or terminal value. (See “How the Horizon Value Affects Deal Framing.”)

A discounted cash flow analysis works well when you understand the causal model and are able to predict the cash flows with reasonable certainty. However, these valuations do very little to place acquisitions in the context of a long-term strategy, where interrelated investment opportunities must be weighed against uncertainties — be they global, industry, or company-specific uncertainties. Indeed, in the midst of uncertainty, a discounted cash flow scenario, however incomplete, can bolster executives’ sense of confidence, justify false assumptions about control over the realization of synergies and create unrealistically low perceptions of volatility.

In a typical company valuation, 50% to 80% of the discounted cash flow value stems from the horizon value. When the present value of the projected cash flows in the estimation period is low, an executive team’s acquisition decision will be a balancing act between the horizon value and the negotiated price. In “hot” markets, when executives may have recently experienced acquisition successes (or seen others do so), they tend to emphasize the future horizon value; in “cold” markets, they emphasize the perceived high risk of making the investment. Therefore, treating acquisition decisions as simple go/no-go choices based on expected cash flows creates an unhealthy dynamic and seems to push executives to extremes: either to rush into action or to hold back on making deals.

Why Managers Value Deals Too Highly

There are several reasons why executives in “hot” deal markets overestimate the horizon value of potential acquisitions and overpay for investments, including (1) financial market exuberance; (2) herding behavior by investors; and (3) executives’ uncertainty biases.

Financial market exuberance

Experience shows that strong markets can get ahead of themselves.4 For instance, high valuations at the peak of the 2000-2001 market induced decision makers to structure many acquisitions for dotcom and telecommunications companies at record prices. Prices were based on multiples of recent transactions without any meaningful adjustments; in many instances, those recent deal prices themselves were out of line. For example, from the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Christopher Gent, then-CEO of Vodafone Group, grew the company from a small U.K.-based mobile operator into a world leader. Some of the company’s acquisitions, executed at a time when the deal market was hot, were seen as overpriced by the investor community and largely financed by Vodafone’s own overpriced shares.

Herding behavior by investors

In “hot” deal markets, competition for what investors see as a shrinking pool of available deals can greatly strengthen executives’ perceptions about the urgency of making acquisitions. This can promote a now-or-never view on acquisitions and frenzied waves of mergers.

Decision-making biases under uncertainty

Executive confidence is a critical factor in a company’s success. But it can become a serious liability when executives become overconfident and overoptimistic about their acquisitions. Groupthink by board members can accentuate the dangers, as can input from investment bankers, who have an obvious self-interest in getting executives to make more and bigger deals.

How the Horizon Value Affects Deal Framing

In discounted cash flow analysis, a potential acquisition’s value is usually based on the value expected to be generated by the transaction during the estimation or planning period, plus the anticipated value down the road, often called the horizon value. In a typical company valuation, 50% to 80% of the discounted cash flow value stems from the horizon value. In “hot” deal markets, executives may overestimate the horizon value of potential acquisitions and, as a result, overpay for deals. In “cold” deal markets they focus on the short-term risk of the investment or price.

Why Managers Undervalue Deals

The opposite side of the coin is understanding why executives undervalue investments in weak markets. An approach that uses overly conservative discounted cash flow valuations in “cold” markets can prove just as problematic as market exuberance in “hot” markets. When managers focus on short-term risk, the following issues can arise:

Faulty benchmarks for market valuations

Coming up with reasonable deal valuations depends first and foremost on selecting appropriate comparison transactions. Comparison transactions chosen in “cold” deal markets can lead to acquirers using multiples that are too low at a time when management of the target company is pegging the value to transactions with higher valuations. This results in markedly different valuations. As a result, the two sides have difficulty finding agreement.

Moving too slowly

When the threat of preemption from rivals seems remote, executives often feel they can afford to wait to complete acquisitions. However, it’s important to recognize that waiting has its costs. In delaying investment decisions, companies can miss out on valuable growth opportunities.

Executives’ narrow view of the deal

Discounted cash flow analyses that are overly conservative may cause CEOs to underestimate the long-term strategic importance of acquisitions. At the same time, executives, focusing on the reduced valuation of their own companies, may hesitate to pursue mergers and other strategic projects during down cycles. In times of uncertainty, executives can suffer from short-termism and fail to recognize the potential of an investment to add value.5

Taking a Broader View

We propose that CEOs correct their valuation biases by applying two theories for decision making under uncertainty that would help offset the illusion of clarity and control gained from using overly static valuations: real options and behavioral economics. Real options refer to choices managers and investors must make about whether and how to proceed with business investments now and in the future. Decisions about whether to make a seed investment or add to an existing investment, for example, create new options to execute follow-on investments.6 A dynamic approach to acquisition decisions gained from real options theory would force executives to become more disciplined about considering uncertainty and contingencies. It would push them to set up explicit milestones that could indicate when initial decisions needed to be adjusted and alternative actions considered. It would require executives to consider in detail the most important options, such as staging or deferring acquisitions, growth options and exit and divestment options.

A Valuation Checklist for “Hot” Deal Markets

In “hot” deal markets, the acquisition team should ask critical questions and perform checks to mitigate overoptimism and overvaluation in the discounted cash flow analysis; they should also view the proposed transaction from a real options lens to counter overconfidence and an illusion of control.

Like hedging with financial options, incorporating a real options mind-set in business changes the shape of the uncertainty distribution of an investment’s payoff. It allows the team to capitalize on the upside opportunities or limit losses on the downside. Compared to a go/no-go trade-off between value and target price in a traditional discounted cash flow analysis, considering real options that hold back the cost of the investment changes the deal to limit downward losses, while value-enhancing real options typically allow executives to utilize upward potential. Thus, applying real options changes the decision dynamic. It can both hedge losses due to high prices in “hot” deal markets and acknowledge the future upward potential of options in “cold” deal markets.

Examples of real options that hold back investment are the option to defer deals and the option to stage the investment and give management incentives to adapt the timing and staging of investments in sympathy with resolution of uncertainty. For instance, instead of pursuing a full acquisition, a company can first acquire a minority stake as a real option to acquire full control later as some of the uncertainty about the target is resolved. The minority stake can be seen as a call option on the remaining stake in the company.7 Compared to a full acquisition, the downside risk is limited to the price of the initial investment.

By contrast, value-enhancing real options “force” executives to consider upward potential and bring a more venturing perspective to a traditional discounted cash flow analysis; rather than holding back an investment, they move investment forward, even under uncertainty. Examples of value-enhancing long-term growth options include the value of identifiable new opportunities beyond the acquisition itself — follow-on options including organic or acquisitive growth that can be exercised when conditions become more conducive. For instance, an acquirer might initially pursue one or more platform acquisitions in a related industry or geography before leveraging its newly acquired core competencies, efficiencies or brand name into follow-on acquisitions.8 Growth options or future exit opportunities9 give managers vehicles for moving ahead to a new stage of investment if and when it becomes beneficial to do so.

Experienced deal makers find such ways to limit investment losses while simultaneously preserving upward value potential. Venture capitalists and serial acquirers intuitively use both sides of optionality in their early-stage investments to resolve the uncertainty inherent in startup ventures; for example, venture capitalists cut their second-round investments in failing ventures while maximizing second-round financing of new growth options in successful ventures. Staging an investment in this way limits the downside risk of the portfolio of failing ventures, and it creates upward potential with long-term options to proceed to the next stage of the successful ones.

Use minority stakes to exercise caution in “hot” deal markets. Rather than approaching acquisitions as “now-or-never” investment opportunities, real options theory suggests that, in “hot” deal markets, companies should respond cautiously by staging investments and waiting to react to changes in demand or overall economic conditions before executing the next step. Taking a minority stake instead of making a full acquisition helps managers to recoup their initial investment and provides an option to abandon their interest in the business. For example, after growing a small mining company into a multinational enterprise, the chief executive made an offer to buy a specialized mining company in the midst of the “hot” deal market of early 2008. But with signs that the economy was slowing and becoming more uncertain, the acquirer withdrew its cash offer for the full company, a move that caused the target company’s share price to drop by 50% (far below the offer price). The acquirer returned to the market and purchased another 14% of the target company’s shares, taking its holding to 25% (without making an offer) and creating a valuable option if and when the market revived. This example illustrates the value of staging acquisitions in “hot” markets that may soon be cooling. It also points to the importance of (1) guarding against discounted cash flow overvaluation in “hot” deal markets and (2) considering the uncertain context of the deal in a real options analysis.

First, a “hot” market requires adjustments in the discounted cash flow valuation and several benchmark checks. (See “A Valuation Checklist for ‘Hot’ Deal Markets.”) Excessive discounted cash flow valuations can actually be tempered when analysts are forced to meet simple consistency requirements that compare the price-to-profitability10 multiple with the one that is assumed at the horizon in the discounted cash flow calculation. Moreover, future profitability and growth will typically decline from the top of the acquisition cycle. By comparing the discounted cash flow horizon value input estimates against longer-term averages of profitability estimates and growth rates, managers should be able to keep overoptimistic horizon values from inflating the discounted cash flow valuation. Once the discounted cash flow analysis is complete, managers should subject calculations to a reality check, using averages of industry benchmarks from the past three to seven years.

Second, in “hot” deal markets, the ability to modify discounted cash flow analyses using the context of uncertainty and of investment-limiting real options — rather than value-enhancing real options — should make growth-minded executives more cautious about entering into bidding wars and encourage managers to focus on changing the timing and amount of the investment in light of uncertainty. The traditional discounted cash flow method recommends an instant response to the full acquisition; a real options perspective, however, offers the opportunity to stage investments and to wait until uncertainty resolves before making the next move. After a company acquires a minority equity stake, it can treat that as an acquisition option; in the meantime, it can discover valuable information about the target’s future prospects, which then supports further decision making as to whether and when to complete the acquisition. As with the maturing of any option, a full acquisition takes time to complete, during which the economic environment may change and the acquirer can review its intentions.11

A Valuation Checklist for “Cold” Deal Markets

Avoiding overly conservative framing of a deal in “cold” markets requires checks to confirm consistency of the bid and valuation assumptions, correction of discounted cash flow variables and adjustments of comparable valuation benchmarks in financial markets. A real options analysis in a “cold” deal market should focus on any overlooked embedded growth, abandonment and exit options in the company’s value.

The option to defer is applicable to many acquisition decisions and is based on two characteristics that are typical of any investment: irreversibility and uncertainty about the value. If an acquisition’s value falls and the project turns out to be a bad investment, it may not be possible to fully recover the investment, acquisition premium and advisors’ costs by selling the assets to another investor; in other words, the investment may be difficult or costly to reverse. Given the various uncertainties affecting future value, irreversible acquisition decisions should be made with caution. Thus, in a “hot” deal market, a real options view should encourage management to delay investment in an irreversible project if a net present value analysis suggests it can only earn the opportunity cost of capital. By incorporating threshold levels into the initial decision making about a deal, real options analysis makes it easier for managers to subsequently defer or let go of intended acquisition targets when conditions are unfavorable — without such reversals implying personal defeats.

In “cold” deal markets, look for future, longer-term growth options. Valuations using classical discounted cash flow approaches can be affected by “cold” deal framing when they ignore long-term contingencies under uncertainty. A management team with a static view may not envision the full range of their real options or they may feel reluctant to terminate operations or abandon assets. When a company’s financial market value is close to its discounted cash flow stand-alone value (implying little or no embedded optionality), the company is vulnerable to opportunistic investors. Some private equity investors are natural opportunists, always on the lookout for ways to reposition their investments. Back in 2004, when the retail industry in the Netherlands was depressed, for example, a leading Dutch retailer operating in numerous formats was acquired by a consortium of private equity investors for €2.5 billion (about $3 billion). Part of the purchase price (about one third) was financed by loans from three banks. Given that the market was cold, the deal could not have been more opportunistic: The company was two weeks away from reporting weak fourth-quarter sales, and the time frame for an economic recovery was uncertain. These factors increased the likelihood that shareholders and management would favor a cash offer.

The investors recognized value-enhancing options that were not embedded in the “cold” market valuation. They had choices as to how to approach the investment. One was to increase their horizon or exit value by selling and leasing back part of the business’s property portfolio and securing a significant proportion of value. Indeed, when we consider this deal through a real options lens, the investors were actually buying the company with a future put option — an exit option for the real estate. In addition to selling off real estate, the investors had opportunities to dismantle parts of its business portfolio. They began by selling a retail chain in 2007; eventually, they divested many other parts of the company.

This case shows that considering the full range of exit options can be a helpful step for triggering decisions about how to restructure and reposition businesses to adjust to demand changes. Whatever the market conditions are — hot or cold — executives should take time to assess the full array of opportunities. For example, when employing a discounted cash flow calculation in a “cold” deal market, checking the price for consistency with valuation assumptions and correcting the cash flow estimates over the cycle should help avoid overly pessimistic valuations. (See “A Valuation Checklist for ‘Cold’ Deal Markets.”) However, the analysis can go further. Viewing the same company through a real options lens can help managers identify opportunities to turn assets to alternative uses. In short, this view treats businesses as a portfolio that can be managed for divestment and exit.

In “cold” deal markets — when negative framing places excessive focus on risk and executives freeze because they are afraid of taking losses — the emphasis should be on value-enhancing optionality. Options thinking, and specifying conditional actions (either divestiture or growth) as real options, can redirect decision makers’ short-term profitability focus toward long-term growth or exit options. A real options view includes knowing how to weigh the value of new opportunities beyond the acquisition itself — options that can be exercised if and when conditions improve. Such horizon value contingencies may have put options characteristics, perhaps leading to an exit on favorable terms through sale to another company. But a real options view also encompasses opportunities with call option characteristics, such as the broad spectrum of investments undertaken for growth and expansion purposes. An acquisition to access a new market or a joint venture can be a beachhead into a new sector. In this sense, an acquisition option leading to further investment opportunities can alter a company’s strategic course and position and can be seen as the first stage in a sequence of interrelated investment opportunities.

Of course, any method of analysis intended to support rational investment and acquisition decisions will become a sideshow if the CEO is already committed to making (or not making) a given investment. This is a serious issue. Psychological studies show that, even with feedback, decision makers find it difficult to recognize their own biases. We try to address this obstacle in acquisition decisions by asking executives to look at something that’s easier to observe than their own minds. Executives can then determine which situations require more caution and which situations justify a more adventurous stance. Executives can learn to apply “self-correcting” tools and valuation procedures to adjust valuations in “hot” or “cold” deal markets. Smart managers can learn to apply behavioral finance and other methods that allow them to exercise the right kind of discipline for the market at hand.

Han Smit is a professor of corporate finance at the School of Economics of the Erasmus University Rotterdam in the Netherlands, a member of the Erasmus Research Institute of Management and coauthor, with Thras Moraitis, of the forthcoming book Playing at Acquisitions: Behavioral Option Games (Princeton University Press, in press). Dan Lovallo is a professor of business strategy at the University of Sydney Business School in Australia, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Business Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley and a senior advisor to McKinsey & Co.

References

1. See A. Tversky and D. Kahneman, “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice,” Science 211, no. 4481 (January 1981): 453-458. For an overview of psychology in finance, see, for instance, N. Barberis and R. Thaler, “A Survey of Behavioral Finance,” in “Handbook of the Economics of Finance,” ed. G.M. Constantinides, M. Harris and R.M. Stulz (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2003), 1052-1114; and M. Baker, R. Ruback and J. Wurgler, “Behavioral Corporate Finance: A Survey,” in “The Handbook of Corporate Finance: Empirical Corporate Finance,” ed. B.E. Eckbo (New York: Elsevier, 2004), 351-417. For a discussion of the impact of biases on practical acquisition decision making, see, for instance, D. Kahneman and D. Lovallo, “Timid Choices and Bold Forecasts: A Cognitive Perspective on Risk Taking,” Management Science 39, no.1 (January 1993): 17-31.

2. This resembles the disposition effect. See H. Shefrin and M. Statman, “The Disposition to Sell Winners Too Early and Ride Losers Too Long: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Finance 40, no. 3 (July 1985): 777-790; and I.M. Duhaime and C.R. Schwenk, “Conjectures on Cognitive Simplification in Acquisition and Divestment Decision Making,” Academy of Management Review 10, no. 2 (April 1985): 287-295.

3. Executives tend to know if deal markets are hot or cold, and that is much easier to assess than their own biases. In times of financial market exuberance, frenzied behavior by acquirers and executive focus on value, a high number of acquisitions should indicate a “hot” deal market. In times of financial market pessimism, passive investor behavior and executive focus on risk, a low number of acquisitions should indicate a “cold” deal market.

4. See R.J. Shiller, “Irrational Exuberance” (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000).

5. Experimental evidence shows that people who are offered a new gamble tend to evaluate it in isolation from other risks. For instance, see N. Barberis and M. Huang, “The Loss Aversion/Narrow Framing Approach to the Stock Market Pricing and Participation Puzzles,” in “Handbook of the Equity Risk Premium,” ed. R. Mehra (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2008).

6. For further reading on real options, see A.K. Dixit and R.S. Pindyck, “Investment Under Uncertainty” (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994); H.T.J. Smit and L. Trigeorgis, “Strategic Investment: Real Options and Games” (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2004); and L. Trigeorgis, “Real Options: Managerial Flexibility and Strategy in Resource Allocation” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1996).

7. This option is exercised (with the bid being equivalent to the exercise price) only if positive economic developments increase the payoff from the full acquisition. Like all call options, the greater the uncertainty, the greater the potential upside (profit) potential, whereas the downside risk is limited to the premium of the option.

8. In such cases, the acquisition forms the underpinning factor that provides the optionality to proceed to the next stage, if and when it becomes beneficial to do so. Such an investment can have high growth option value when it involves an option on options, or a compound call option. Following this approach, new growth options and uncertainty can actually move investment forward.

9. In addition to call real options — for example, to defer, stage or grow — put real options also exist to divest part of the company early. When restructuring a company, an investor may consider company assets as a portfolio of put options. When the present value of the remaining cash flows of part of a business falls below the resale value to a potential buyer, the asset may be sold — effectively exercising the owner’s put option.

10. For instance, EBITA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes and Amortization) is a measure for operating profitability that uses accounting data that corrects for the financing structure of the company. A related measure, EBITDA, also corrects for depreciation.

11. This is similar to a call option on the value of synergistic benefits, where the exercise price is the cost of the merger.

i. See H.T.J. Smit and T. Moraitis, “Playing at Acquisitions: Behavioral Option Games” (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, in press).

Reprint 56109.

For ordering information, visit our FAQ page. Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2014. All rights reserved.