Chapter 13

First Steps and Missteps

Time is a great teacher, but unfortunately it kills all its pupils.

—LOUIS-HECTOR BERLIOZ

If you have made it to this point in the book, let’s assume that you have conceptually bought into the idea that contextual pricing is worth a try. The question now becomes: how to implement these ideas?

There are two parts to conducting a trial of the framework prescribed in this book: (1) Deciding where, when and how, and (2) Strategizing how to overcome opposition. Let’s deal with the second point first, since it is more interesting.

Overcoming Opposition

There is always opposition to pricing changes. Pricing is inherently political—someone will feel threatened if there is a change. Why? Because, for instance, change may upset long-standing relationships with customers who have become friends, it may undercut the importance of a manager’s role, it may seem to intrude into their customary modus operandi, or it may go against their belief system.1 Better pricing can gather adherents quickly, but rarely is there universal support.

Some of the opposition is a function of understanding. If all management were more familiar with pricing, there would be less fear, and less opposition. It is the lack of understanding that makes many organizations fear change because they cannot precisely see the consequences of it. By way of analogy: if a group of finance managers were told that henceforth debits would inhabit the right-hand ledger column and credits the left hand, contrary to past practice, they might grumble, but there would be little fear that it would bring disaster. Say the same thing to nonfinancially savvy managers and there might be cries that this was illegal and Enron-esque. Similarly, if a group of market communications managers were told that all e-mails to the company website had to be answered honestly and fully, they might also grumble, but they would be confident they could handle it. Say the same thing to inward-facing operational staff and there would be fear of fatal disclosure of secrets and embarrassment.

Opponents of pricing programs usually don’t understand—and often don’t want to understand—pricing logic. When they don’t understand the logic, and it seems to differ from their vague impressions of what pricing should look like, and since pricing has the potential to have an impact on their livelihoods, then they will feel high anxiety. For example, it will feel safer to try yet another branding campaign or another sales force reorganization or another product tweak than to open Pandora’s pricing box. As Mark Nevins, Ph.D., a well-known organizational behavior expert, once observed: “When people don’t know what to do, they do what they know.”

You could try to educate the skeptics, but that takes time. If you have the clout, you could mandate it, but there are always opportunities to sabotage an implementation: the systems won’t support it, the sales force won’t implement it, the legal staff won’t approve it. The way to overcome the opposition is to find champions who will try it on their turf.

With the right advocate, a good idea becomes possible. Case in point: a CMO at a search engine company had a task force use the principles outlined in Chapter 7 (on scientific bundling) to rebuild a key new service bundle about to be launched. As often happens, the science suggested fewer components to the bundle and a higher price—about twice the old offering.

This did not play well with the sales force. Their understanding of price was that more stuff meant more value (wrong) and lower price meant higher volume (often wrong). A rebellion broke out at bundle launch time. The sales force wanted an earlier iteration of the new bundle, which had more components, and was tagged for a lower price.

Not good, but fortunately the VP of marketing (now CEO) and the VP of sales were very smart. They asked, “Do any of the sales managers want to try selling the new bundle?” As it turned out, yes, a few sales managers did like the new bundle, and they were given it to sell. The rest were given the original bundle.

Six months later, the group selling the new bundle had outsold the broader group twofold (in unit terms, not merely dollars). Now the rest of the sales force wanted to sell the new bundle, which the CMO was more than happy to allow. The side-by-side trial had proven useful, indeed.

Had the former rebels learned that in a bundle context too many components actually destroyed value? That a coherent and focused bundle could command more than a big flabby bundle? We suspect not. Contextual pricing had won in the market, but resistance to change and distain for pricing theory die hard.

The Importance of Champions

“It worked, we want it” is an attitude that has broad sales applicability. Therefore we recommend starting with champions. You may be a champion, but you need other champions all along the delivery chain: in IT, in sales, in product development, in product management, in customer service. Even if all these functions report to you, the need to pick effective advocates remains key to success, so choose the right champion even if he or she is not in the ideal product or market group.

Champions, as you know, are smart, driven, open to new ideas, respected within the organization, may have knife scars on their backs, and must have some authority. They must also be equipped with an appealing price reform message for key stakeholders. This can be the promise to cure an ongoing sales “pain point,” better pricing for an innovative new product, or anything that requires change and there is no entrenched denial.2

Examples of pain points include a pricing structure customers hate, repeat price level complaints in certain types of contexts and lack of organizational incentives to perform due to lack of ability to charge. For instance, at Johnson & Johnson the pain point was pressure from competitors offering dental floss at a lower price. J&J responded by reducing the yards of floss inside each box and then matched the price per box of the competition. Since apparently customers buy by the box, this was a sufficient price structure response to the competition.

Depending on resources available, you also need to think about the scope of early efforts. If you are trying to cure a pain point, consider why your pricing is frequently under pressure. Is the problem specific (like the dental floss), which pricing can address narrowly, or does it require a comprehensive revamp of all pricing? If the problem is discounting, the initial effort may cure it completely.

Understanding the different contexts for selling and ensuring that sales and other functions are equipped with a suite of robust contextual prices will go a long way. But not all problems can be solved by price alone. If the problem is an obsolete product offer, pricing will only make the best of a bad situation. Pricing would not have saved the candy concession stand sales on the Titanic as the ship slid beneath the waves.3

The Front-End Choice

Contextual pricing has been successful both with a “strategy” front end and with a “systems” front end. Each has its advantages and a different risk profile. Which is better for your company will depend on the state of its pricing practices, degree of buy-in to pricing improvement, objectives, and budget constraints.

A Strategy Approach

A strategy front end is the better choice when your company has reasonable pricing practices, indifferent but not rebellious market-facing management, only a little money to invest, and adequate systems capabilities. The opening thrust of a strategy approach will run through a set of eight steps, as follows:

1. Find champions, socialize them and strategize the obstacles.

2. Pick a target: new products, or a product or segment experiencing pain points related to price. Check that this is actually narrow enough for trial.

3. Understand the market (market contexts, drivers).

4. Develop the necessary 20 or so contextual base prices, or develop a tool that produces these prices. Develop the accompanying price structures (remember the pricing trinity of context, structure, and level).

5. Don’t let the trial be sabotaged. Stick with the baseline prices, otherwise the discipline necessary to focus pricing will evaporate.

6. Evaluate results, go/no-go, and expand rollout.

7. Create replicable processes; make sure there are supporting

a. Contextual information sources

b. Systems

c. Culture

8. Make process improvements as needed.

The big advantage of this program is that it should pay for itself as you move along the path. If the initial area chosen produces the likely 7 to 15 percent or more revenue increase, then the program will probably have paid for itself, and more. Subsequently rolling it out to other products or markets will leverage that initial investment for even better returns.

The risks of a strategy front end may also lower. The strategy front end will look the problem straight in the eyes, give you an answer, and allow an assessment of whether your management team and systems infrastructure can support the answer. That is why systems competence must be at least adequate to support the answer, and there must be some budget to support a deep-dive market look.

A Systems Approach

A systems-led approach shows a very different profile than a strategy-led one. This approach tends to be better when pricing practices are in disarray, pricing appears to be materially suboptimal, operational management is stubborn and rebellious, and there is top management determination and budget. In some ways it says, “I assume we can handle the market, but first I need to train my troops.”

A systems-led effort is appropriate because a set of pricing analytic tools, CRM functionality, and price-administration tools will be needed to get the job done. You still need to analyze the market to understand contexts and price drivers—it’s just that the biggest obstacles will lie internally in your company, and they must be addressed.

Whereas a company with relatively disciplined management can make do with stand-alone tools and informal communication systems, companies with sales and marketing cowboys need strong systems integrity. Sales management in some cases needs to be blocked from persisting in old pricing practices, and product management may play games with informal systems (e.g., fulfilling the form, but not the substance, of the program so that contextual relationships are thwarted, or making up results). There may also be a need to tie compensation systems and pricing systems together at some level.

The other benefit of a systems-led approach is that more formalized price administration can show benefits regardless of the underlying pricing strategy. Simply requiring CRM inputs of relevant contextual account information can help reign in salespeople and makes the threat of them leaving less of an issue. Finally, the system itself is a strong symbol of corporate determination: Managers will understand that after investing $20 million in the new system, as part of a project led by a former business unit head, that management is determined. Change may be a condition of employment.

The Program Details

Having considered two major options for change, some detail on program steps is appropriate. Here is a healthy dose of warnings that should assist you in deciding which avenue to pursue.

Information Sources

Developing the price structures and tools, which can drive contextual pricing, require information. As described in Chapter 15, your company may have less of the required information than you might expect.

Information sources must include all the factors that drive price. Not just the impoverished scraps of knowledge currently feeding the price decisions, but radically taking into consideration how customers actually buy. What goes on mentally, or organizationally, as consumers and companies decide to purchase. That may sound like old news, but in fact companies commonly ignore these factors and so fall short of actually incorporating context in pricing.

Sources of information may take many forms:

![]() Interviews, either one on one, in panels, or in focus groups

Interviews, either one on one, in panels, or in focus groups

![]() A detailed model of your customer’s economics or their business, showing how they make financial and purchase decisions

A detailed model of your customer’s economics or their business, showing how they make financial and purchase decisions

![]() Conjoint or other analysis of customer views, or

Conjoint or other analysis of customer views, or

![]() Best of all, a rigorous analysis of customer behavior and testing of purchase/price behavior through regression or similar techniques

Best of all, a rigorous analysis of customer behavior and testing of purchase/price behavior through regression or similar techniques

![]() Market tests, such as those employed by large consumer products companies (and underutilized by most industries)

Market tests, such as those employed by large consumer products companies (and underutilized by most industries)

Note how we did not list surveys among this set of tools. Surveys are excellent means for adding precision to market questions where the broad parameters of the answer are already known, and questions to which a respondent can give a rapid answer: Who influences the buying decision? Which brand do you trust most? What are the alternatives? Surveys are not ideal for identifying new contextual parameters of decision making.

Beware of relying on some of the established providers of market research. While they often claim to have expertise in pricing, they tend to be focused on research on price level; this misses critical questions regarding price structure and drivers of price. We find that often focus on price level misses opportunities to address pricing opportunities through structure or messaging.

One time we were called in to comment on pricing at a leading textbook publisher. It had used a well-known polling company to conduct a survey asking college bookstores why they would stock certain teaching aids. The first page of the survey results showed a pie chart with answers to “Why would you not want to carry this product?” The answers came back in two major categories: about 25 percent of respondents cited non-price factors, including convenience, product, and shelf space. About 75 percent of respondents said price. The audience looked forward in anticipation of seeing a breakout of the 75 percent answer of price.

But no, the next slide gave a further breakout of the product and convenience response slices of the main pie chart. No mention of why price was not acceptable was ever presented. Was it the price/performance ratio? Was it price relative to a substitute teaching aid? Was it the absolute price level? Was it lack of understanding by potential buyers? Was it the cost of stocking relative to the margin on the teaching aid (i.e., was the price too low?) The answer to why was not to be found in the professionally administered survey of buyers. A wasted opportunity, indeed.

Contextual pricing does not mean your company needs to learn a new set of tools, but it may mean you need to provide more guidance to your market research suppliers.

Worse yet, established survey companies sometimes fail to adjust for three important factors in gathering evidence on pricing:

1. Respondents lie.

2. Often the trend is more important than the static situation.

3. Respondents are not inclined to work hard to really distinguish among options, so what will be big differences when they are actually asked to spend do not appear so large in surveys.

More reprehensible than respondent failings, surveyer use of boilerplate (stock) survey questions rarely match the market. For an educational-testing provider, the survey house substituted its stock affordability questions for the internally developed ones. Not surprisingly, in an industry under severe funding shortages, all the respondents checked the “severe budget squeeze” box, although many went on to buy the service.

Sadly, pricing is not a popularity contest nor is it often a win-win situation. Most buyers understand that, and so they game their responses when they see a likely benefit. Therefore, questions regarding price must be developed so that gaming is minimized. (It’s tough to adjust for gaming—better to get it right from the start.) Some techniques for getting at the right answer include:

![]() Ask questions about relative, not absolute, price preferences. Everyone can figure out that answering “What would you pay for this?” calls for checking a lower number. However, “Would you pay twice as much for multigaming capacity as for single game capacity?” is harder to game, plus the answers give the pricers some structural cues. Finally, it gives the respondent the relevant context for the pricing judgment.

Ask questions about relative, not absolute, price preferences. Everyone can figure out that answering “What would you pay for this?” calls for checking a lower number. However, “Would you pay twice as much for multigaming capacity as for single game capacity?” is harder to game, plus the answers give the pricers some structural cues. Finally, it gives the respondent the relevant context for the pricing judgment.

![]() Test customer and potential-customer actions in addition to their responses. For instance, in a survey of multidwelling residential units and their telephone service buying preferences, using surveys and buyer interviews, the surveys produced a roughly even split between price and service being their top priorities (service was slightly ahead) among large property-management firms. When we timed the interviewee comments on price terms and service, however, it was a clean sweep: 100 percent of the large-entity respondents spent far more time talking about price and terms. This was then confirmed by looking at actual win/loss data, service records, and price differences. (Interestingly, smaller property management companies faithfully reflected their survey service/price answers.)

Test customer and potential-customer actions in addition to their responses. For instance, in a survey of multidwelling residential units and their telephone service buying preferences, using surveys and buyer interviews, the surveys produced a roughly even split between price and service being their top priorities (service was slightly ahead) among large property-management firms. When we timed the interviewee comments on price terms and service, however, it was a clean sweep: 100 percent of the large-entity respondents spent far more time talking about price and terms. This was then confirmed by looking at actual win/loss data, service records, and price differences. (Interestingly, smaller property management companies faithfully reflected their survey service/price answers.)

Market surveys also need to reflect market trends, while many surveys and other vehicles tend to be static—it’s easier for people to answer what they are doing now. This is important to the research company because survey duration matters to their costs, and they can be detached from whether it actually reflects actions.

For a leading cable company, the static analysis of existing customers showed that there was no discernable difference in pricing for bundles that violated bundling rules (contained in Chapter 7) and bundles built in accordance with market bundling rules. For new sales, however, offers which reflected bundling rules experienced a lower discount and higher penetration. Since management was focused on new sales, this also was the more important pricing focus.4

We find that in many markets, it is changes in them that are the avenue for revenue improvement. Most surveys tend to resist incorporating both questions about the present and the future because that doubles the length of the survey. To avoid this, management might want to use other analytic tools before the survey stage, to rapidly home in on whether the current situation or trend is more relevant to pricing.

Again, the point is that market research firms applying standard questions and survey techniques to pricing questions often come up short or with mistaken conclusions. Worse than being useless, this supposed lack of conclusive data support for pricing actions empowers those who prefer doing nothing and those who prefer to guess.

As you think about your company’s research into context, make sure that management actually investigates context.5 A test of whether researchers are actually investigating context is whether the questions ask about differences in context. Here are some examples of differences in relevant context:

![]() Aftermarket price of the same car radio for a luxury car shows 0.82 price elasticity; for an economy car, elasticity measures 1.30.

Aftermarket price of the same car radio for a luxury car shows 0.82 price elasticity; for an economy car, elasticity measures 1.30.

![]() Telephony VoIP service shows 0.32 price elasticity when sold with a broadband access package, but elasticity of 1.25 if sold alone.

Telephony VoIP service shows 0.32 price elasticity when sold with a broadband access package, but elasticity of 1.25 if sold alone.

![]() WIMAX wireless broadband access is viewed as a complement to cable or telco (DSL) wire-line broadband access to people who travel on business, but seen as a substitute by those who work at fixed locations.

WIMAX wireless broadband access is viewed as a complement to cable or telco (DSL) wire-line broadband access to people who travel on business, but seen as a substitute by those who work at fixed locations.

![]() Price sensitivity for direct-mail and e-mail-blast services varies along with the lifetime value of the product being promoted. In one market, a credit card solicitation had seven times the lifetime NPV (net present value) of a phone-service solicitation, and this translated into higher direct-mailer willingness to pay.

Price sensitivity for direct-mail and e-mail-blast services varies along with the lifetime value of the product being promoted. In one market, a credit card solicitation had seven times the lifetime NPV (net present value) of a phone-service solicitation, and this translated into higher direct-mailer willingness to pay.

The point of this short list of examples is that to test pricing hypotheses, there needs to be a good understanding of underlying economics, uses, business processes, decision processes, and the consumer’s mind. Doing so requires a sophisticated, multistep inquiry. If compressed into one-step research, much will be missed.

Very much in the tradition of great consumer management, we find that tools can and should be used sequentially. Often they are not used sequentially, because pricing is a hurried afterthought, and so time is limited. That is not the best practice! The best practice is to define the scope of potential contexts and then develop a list of contextual pricing candidates. At that point, you have the basic information required to test and make contextual pricing operational. In this second phase, modeling, surveying, and other examination of market behaviors and references are possible.

So, the best practice is to first create a wide funnel for potential market drivers, then narrow it by looking at the evidence, and meld it into a coherent contextually based set of decision rules. This should induce more confidence in pricing programs.

Implementation

To address context fully requires cutting across many organizational silos, in addition to building understanding of what goes on in the market. To make product development, marketing, sales, finance, customer service, and other departments fully cognizant of context would require a shift in culture and focus at most companies. The good news is, however, that with your next market initiative or product, you can begin to move toward contextual pricing.

If possible, begin the next initiative with a symbol of why this is important. For instance, one year the former chairman of BellSouth (now AT&T) publically designated his top priority for the year as pricing and put his heir-apparent in charge of the initiative. Doing so was a clear symbol and sent a powerful message.

This is highly appropriate. Pricing is the embodiment of your company’s mission—it transcends any given department and dominates your financial top line. Yet in many companies the pricing function underper-forms and is nowhere near to living up to its potential. Unless your company has a CEO/COO-led revenue management culture, it is likely that pricing is frequently neglected, underresourced, and ad hoc. Yet it could grow to be the most powerful driver of revenue improvement. A classic example of top-level influence was when Lee Iacocca, head of Ford, set the price target range for the Ford Mustang, apparently to the disappointment of his development team.

It is good to have a top management symbol of company determination to improve pricing.

Process Improvement

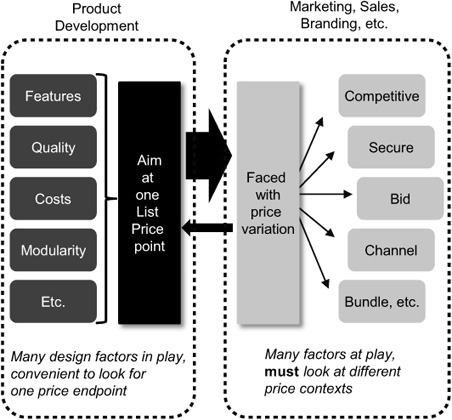

Today, a typical corporate pricing process is to start with a target list price and then tear it down. The pattern looks somewhat like Figure 13-1.

Figure 13-1 Managerial focus—the Great Divide: differences between “upstream” product development focus and “downstream” market facing pricing issues

We suggest that the companies whose pricing flows follow this pattern can do better. Better pricing can result from beginning with a consideration of pricing context, not list price.

Culture and Acceptance

In any company there are likely to be some functional audiences who are still list price advocates. List price is a useful simplification for product designers. In many cases, product designers consider adding or subtracting features and offer components; sanity requires them to have a single scorecard: Has value increased as a result of a specific product improvement? Did it increase by more than the cost of the addition? From the point of view of the product (or service) developer, a single price target linked to one context is a very convenient—perhaps even necessary—benchmark. But as the functional focus moves from product creation to revenues and sales, the utility of list price diminishes. Consider the increasing degree of market contextual detail required by each step in the product development—marketing—sales evolution:

While convenience and isolation from markets allows product development to make do with a single list price, from the point of view of a P&L manager or a product manager or a sales rep, there are a lot of drawbacks to a list price. Influences on price not captured in list price for product managers include advertising and channel reach, which affect only parts of the market. For sales representatives, important influences not captured in list price include client loyalty and specific competitor offers. These are important factors, but not addressable by product development or R&D.

Perhaps the chief danger of creating a list price is that it often marks the end of a well-resourced pricing inquiry. With a list price established, product development signs off and hands the problem to marketing. Marketing hands the problem to sales and operations, etc. These functions must then unravel the consolidated list price and turn it into contextual prices. Often they must do this with fewer resources than went into developing a list price to begin with.

Even with inadequate resources for price study, line management will understand the pricing obtainable from different segments in different circumstances (contexts), but that takes time. Sadly, time is not your friend in setting prices. With the passage of time, more money is left on the table as customers become accustomed to a too-low price. Equally suboptimum is a too-high price, which may leave customers dissatisfied and ready to defect. Recovering from a bad initial price is expensive and difficult, sometimes so difficult that it requires a product relaunch.6

Sometimes more time is spent on “deal” pricing or adjusting discounts rather than initial price setting. This is actually good news. It is a sign your company is moving away from list pricing to contextual pricing, albeit in a roundabout way. The only trouble is that deal pricing is usually focused on one deal at a time, not an overall contextual approach. Hence the wheel must be reinvented with every negotiation. Wouldn’t it be simpler if price were already adapted to contexts such as initial deals, add-on sales, competitive fights, and all the 20 or so common pricing situations?

To be sure, sometimes a list price does have market uses. One of them is that in mass markets the list price communicates a broad value. Often, pricing is the key message on product or service value. This message must be simple, or it cannot be readily conveyed. The actual price paid will often be compared with the public list price. This comparison has its own utility. For instance, the seller of large data archives set the list price 30 percent above the target price because internally buyers were evaluated based on the “discount” obtained. A generous differential makes all buyers look good—they got the discount the seller was more than ready to give them. Sort of like the children of Lake Woebegone, all buyers were made to be above average. But this is the messaging part of pricing, not the price-setting part of pricing.7

List price may have a symbolic or messaging role and is valuable for that reason.

Summary

Inculcating a contextual pricing approach cannot simply rely on the assumption that managers will recognize the market needs it and that the company will do better with contextual pricing. Resistance or indifference will be a powerful force. Resistance may take the form of endless meetings. As Verizon VP of business sales Deb Harris once urged: “Don’t hold meetings about how to get up from your desks!” Develop a strategy employing energetic champions to facilitate implementation. Do not fall prey to hazards in acquiring the right market information. With proven internal success, the program will experience less resistance.

WHAT TO MAKE OF THE DATA?

CHOICE OF DATA ANALYSIS TECHNIQUES

Warren Buffett has a famous preference for making investment decisions based on first-hand experience. Some would call that “grandmother research.” Others might complain about sample size. Perhaps, but it works. Another notable individual, Leonardo da Vinci, once said, “All our knowledge has its origins in our perceptions.” And “Although nature commences with reason and ends in experience it is necessary for us to do the opposite, that is to commence with experience and from this to proceed to investigate the reason.”

This means that management must choose the right scope of inquiry, as described below. Planners and managers must then get their hands dirty by conducting many industry interviews. These will be helpful in establishing some patterns. For example, those interviewed might say, “We used to be centralized and tried to approach the market through a highly disciplined process, but then we met a lot of resistance and the department was split up among several other departments. Everyone does it their own way now.” Or they might say the opposite or some variation in between. The point is to conduct enough interviews to have a large enough inventory of case histories and how change is driving decision-maker frames of reference.

“Large enough” is often a smaller sample than many managers expect. Don’t forget that confidence level is built not only by sample size but also that it is based on how much sample points vary from the predicted pattern. Thus, if sample points are tightly in line with prediction, a very small sample may be adequate.

Also, don’t forget that this is not criminal law, where before someone is sentenced on the basis of fingerprints or other evidence that requires a statistical showing, the confidence level required is 98 percent or higher. That is because defendants are innocent until proven guilty. That is not true of business propositions—here, the best evidence wins. Even more important, intuition is given some weight.

Tools that can help illuminate the data include, of course, our old friends correlation and regression analysis. However, there are other useful tools worth mentioning:

![]() Discriminate function analysis, also known as disjunctive mapping, can help reach conclusions on relationships based on outcomes rather than on a predictive formula or “central tendency.” In other words, it associates events with outcomes without worrying why there is a link.

Discriminate function analysis, also known as disjunctive mapping, can help reach conclusions on relationships based on outcomes rather than on a predictive formula or “central tendency.” In other words, it associates events with outcomes without worrying why there is a link.

![]() Min-max analysis, which could fairly be considered a survey technique rather than an analytic technique (it is both), can help sharpen respondent results by asking them which features they like best and which they like least, for instance. Over rounds of questions, this approach then isolates the most or least important, even if respondents initially say everything is similar in importance.

Min-max analysis, which could fairly be considered a survey technique rather than an analytic technique (it is both), can help sharpen respondent results by asking them which features they like best and which they like least, for instance. Over rounds of questions, this approach then isolates the most or least important, even if respondents initially say everything is similar in importance.

![]() Freeing the data of respondent wishy-washiness and deceit can also be achieved via conjoint analysis.

Freeing the data of respondent wishy-washiness and deceit can also be achieved via conjoint analysis.

![]() Kriging can help interpolate from extreme points. This is useful because often the extreme points (zero value, high value, according to the contextual situation) can be established, and the argument lies in the midpoints.

Kriging can help interpolate from extreme points. This is useful because often the extreme points (zero value, high value, according to the contextual situation) can be established, and the argument lies in the midpoints.

![]() Another tool is simulating markets. Harnessing the wisdom of crowds has proven useful to companies such as Google, Intel, Microsoft, and Best Buy. We like this tool because when these companies have created “prediction markets” that allow employees to forecast a range of prices (e.g., stock prices) and take-up volumes (e.g., for Gmail). Interestingly, often the internal market forecast beats marketing and other forecasts.

Another tool is simulating markets. Harnessing the wisdom of crowds has proven useful to companies such as Google, Intel, Microsoft, and Best Buy. We like this tool because when these companies have created “prediction markets” that allow employees to forecast a range of prices (e.g., stock prices) and take-up volumes (e.g., for Gmail). Interestingly, often the internal market forecast beats marketing and other forecasts.

So there are some tools that take the pricing exercise from raw data to some degree of coherence. No tool, however, brings data to actionable pricing strategies or other conclusions. There is never perfect information for pricing. The final step still lies with humans, who may then build tools to extrapolate from their judgment.

Once the data is in hand, simple smarts will be the engine for selecting what is relevant and extrapolating it to the pricing tools. There will never be perfect information for pricing, but inference is possible. In The Black Swan, a book on statistics and highly infrequent events, the author cautions us that many real life events cannot be predicted on the basis of certainty but rather on “reasoned probability.”8 Note that he does not say mathematical probability: judgment still frames the question. Arthur Conan Doyle, doctor and author of the Sherlock Holmes books, and (incidentally) inventor of the life jacket, once wrote: “From a drop of water … a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other. So all life is a great chain, the nature of which is known whenever we are shown a single link of it.”

Notes

1. Don’t underrate philosophical opposition. While communism may have collapsed in the Soviet Union, it appears to be alive and well in various parts of the Fortune 500. Many managers are offended by the idea of material increases in price and killing off competitors. In one Belgian firm, management also complained that if they instituted a major price increase there would be social repercussions to the management team (e.g., fewer party invites, etc.).

2. Over many years some functions (e.g., sales or customer service) are told that it’s their mission to overcome a flawed pricing structure or inappropriate price points. Because of this, the groups feeling the pain of bad pricing will see it as their mission to deny there is any problem—after all, they are there to fix it. Sometimes the motivation is even simpler, for instance, when the market wants variable (“pay by the drink”) pricing, but the sales force believes that will reduce its sales commissions.

3. That would be either a channel issue or a product issue, depending on how you look at it. In either case, icebergs are not a pricing issue, although we often find that pricing is tied to channel, promotion, or product drivers.

4. Why did the embedded base not reflect compliance with sound bundling principles? We are not sure, but we suspect that the embedded base contained many bundles that were sold when there was still a huge unfulfilled demand for bundles. At that time bundles were bought by bundle enthusiasts, regardless of whether the bundle taxonomy was sound or contained flaws. Perhaps these early bundle buyers would have paid even more for their bundles then, and the lack of discount pattern simply shows that for early buyers there was no price pressure.

5. There are more disconnects than you might expect. After one pricing study, the CEO asked one of the authors of this book to stay to observe the initial implementation. Sitting in on the CMO’s kickoff of the program, I was surprised when she walked up to the podium, blew the dust off of last year’s marketing program document and rallied the troops. Afterward I said, “Lourdes, that is not what you agreed to at last week’s meeting. Her response was, “Yes, but that would have been a lot of work, it’s much easier to just reuse last year’s plan.” True story.

6. Examples include AOL in 2010, Nike in 2009, and the classic 1982 Grey Poupon mustard relaunch. A relaunch is expensive and should be avoided, but it does show that management is decisive about pricing and understands that history is context.

7. The timing and pattern of price moves is highly communicative of your objectives and requirements of business partners. This can be very effective when direct communication is blocked or impractical. For examples, please see Rob Docters, “Price Is a Language,” Journal of Business Strategy, May/June 2003.

8. Nassim Taleb, The Black Swan, Random House, 2007, pp. 50–52. This author echoes Albert Einstein who once commented, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”