Chapter 6. Myth No. 6: No One Can Compete Against Wal-Mart and the Other Big-Box Retailers

Truth No. 6: You Can Compete Against the Big-Box Retailers if You Have the Right Plan

Introduction

One of the main fears that many prospective business owners have is whether they’ll be able to compete against Wal-Mart, Home Depot, Best Buy, and the other big-box retailers. It’s a legitimate fear. The big-box stores continue to grow, not only in terms of size but in terms of geographic breadth and product line. There are now big-box stores in towns as small as 10,000 people. And the stores don’t just sell goods; they sell services, too. For example, Home Depot sells installation services for the carpet it carries, and Best Buy offers at-home computer training and repair. There are also anecdotes, which all of us have heard, of big-box stores moving into towns and driving local merchants out of business. If established businesses can’t compete against Wal-Mart or Home Depot, it’s hard to blame a prospective business owner for worrying about whether his or her business will have any chance at all.

The reality, though, is that despite these obstacles, many small businesses do compete successfully against big-box retailers. Their success, however, is not by chance. While it’s nearly impossible to compete against Wal-Mart and the others on price, price isn’t everything. There are many other forms of competition including product quality, customer service, product knowledge, convenience, ties to the local community, and so on. The businesses that compete successfully against the big-box retailers compete on one or more of these variables and avoid head-to-head competition on price. They also manage their businesses prudently and employ steps to keep their costs in check and to get the word out about the points of differentiation between their businesses and the big guys.

The purpose of this chapter is to more fully explore this important topic. In our view, the notion that no one can compete against Wal-Mart and the other big-box retailers is a myth—but there is a caveat attached. In general, no one can compete against the big-box retailers at their own game. So, if you’re thinking about starting a business that will compete against a big-box retailer (and most businesses do at some level), you have to first understand their game and then develop a strategy and set of tactics that gives people reason to do business with you. In our experience, the big-box retailers are vulnerable but only to businesses that have a firm sense of how to compete against them.

This chapter proceeds in the following manner. First, we describe how the big-box retailers compete and what their vulnerabilities are. Although Wal-Mart, Home Depot, Costco, and the others are different in many ways, their overall strategies and vulnerabilities are similar. Second, we describe the three most common approaches employed by businesses that compete successfully against the big-box stores. Third, we lay out two specific tactics that new businesses use to make these approaches successful.

How Big-Box Retailers Compete and What Their Vulnerabilities Are

There are two categories of big-box retailers. The first are the general merchandise stores, such as Wal-Mart, Kmart, Costco, and BJ’s Wholesale Club. These are the biggest stores, ranging from 50,000 to 225,000 square feet. The second are the category killers, such as Home Depot, Best Buy, PetSmart, Dick’s Sporting Goods, and Bed Bath & Beyond. These stores focus on a single category and offer a wide selection of merchandise in that category. The name "big-box" comes from the physical appearance of the stores. They are normally large, free-standing, rectangular, single-floor stores on a concrete slab.

How the Big-Box Retailers Compete

The general merchandise stores, such as Wal-Mart and Target, compete primarily on price and selection. Although they attract people from all income levels, their most frequent customers are people in middle- and lower-income categories. The stores advertise "everyday low prices" and "one-stop shopping" and carry a wide selection of merchandise, from clothing and electronics to prescription drugs, food, toys, and automotive supplies. A Wal-Mart SuperCenter features up to 142,000 items. The approaches of the stores vary some. Costco and Sam’s Club, for example, target small business owners along with the general public. Costco features a smattering of high quality products, such as Godiva chocolate and Waterford crystal, at bargain prices. Target has differentiated itself within the general merchandise big-box category by featuring more attractive stores with a slightly higher quality mix of merchandise.

The category killers follow much the same strategy but focus on a single category, such as electronics, pet supplies, sporting goods, or toys. While a category killer store, such as Best Buy or PetSmart, is not as large as a Wal-Mart or Costco, the advantage they have is an ability to zero in on a single category and provide better product knowledge. By focusing on a single category, the category killers are also able to generate more passion among their customers than the general merchandise stores.

Behind the scenes, the lower prices the big-box stores offer are made possible by volume sales, supply chain efficiencies, aggressive negotiations with vendors, and low overhead. The big-box concept also relies on Wal-Mart’s original notion of "value loop" retailing as shown in Figure 6.1. The basic idea behind value loop retailing is that low prices generate healthy sales and profits. If a portion of the profits are reinvested in still lower prices, the prices will generate still higher sales and profits. If a portion of these profits are reinvested in still lower prices, sales and profits will continue to rise and so on and so on.1 There is, of course, a limit to how much sales can go up and prices can go down, but it’s easy to see the gist of the strategy.

Figure 6.1. Key to big-box retailers’ success: Value loop pricing

Along with low prices and a broad selection, the big-box stores also pursue a saturation strategy. Wal-Mart has literally blanketed the country with over 1,075 Wal-Mart discount stores, 2,250 Wal-Mart SuperCenter’s, 580 Sam’s Clubs, and a growing number of Wal-Mart Neighborhood Markets. Target now has over 1,500 stores, and Costco has 490. In the category killer group, Home Depot has 1,900 stores, Best Buy has 820, PetSmart has 900, and Beth Bath & Beyond has 815. These stores are not confined to urban areas. As mentioned earlier, Wal-Mart now has SuperCenters in towns as small as 10,000 in population, and the other big-box retailers are following suit. In most parts of the country, consumers have several big-box stores in their immediate shopping areas.

Vulnerabilities of the Big-Box Stores

The big-box stores have several vulnerabilities. The general merchandisers feature a product strategy that is a mile wide and an inch deep, which limits their ability to provide a wide selection of products or superior product knowledge in any one area. The basic idea is to sell the most popular products in as many categories as possible to value-minded consumers. While this approach allows the general merchandisers to achieve economies of scale (think of how many bottles of Tide Wal-Mart sells in a day), it leaves gaps in the marketplace, as explained in Chapter 5. The general merchandise stores are also vulnerable in regard to customer service, product knowledge, and their ability to develop one-on-one relationships with customers. The very nature of Wal-Mart, Kmart, and Costco’s low-cost approach limits the amount they’re willing to invest in customer service, and the sheer number of products they sell makes an intimate knowledge of each product impossible. The large size of their stores is also wearisome for many shoppers, who tire of crowded aisles, long checkout lines, an inability to find what they’re looking for, and the lack of assistance when needed.

The same vulnerabilities that apply to the general merchandise stores apply to the category killers to a slightly lesser degree. Although the category killers, like Home Depot and PetSmart, are generally better at customer service and product knowledge than the general merchandise stores, they’re still trying to sell the most popular products to mainstream consumers, which leaves gaps in the marketplace for others to fill. For example, Dick’s Sporting Goods offers an impressive selection of sporting goods and apparel, but it can’t offer everything. This reality provides an opening for a company like Just For Girls Sports, which is an online store that specializes in products that are especially designed for athletic girls, teens, and women. The category killer stores are also subject to the same criticism that general merchandise stores experience as a result of their size. While some people enjoy browsing around a large store like a Best Buy or a Dick’s Sporting Goods, other people find the experience irritating and tiring.

A vulnerability that applies to both categories of big-box stores, which is most pronounced when a Wal-Mart or a Home Depot enters a smaller town, is a lack of ties to the local community and a perception that the larger store is a threat to local merchants. This issue has resulted in town meetings across the country as local communities have wrestled with the pluses and minuses of allowing big-box retailers to locate in their towns. While big-box stores provide employment and offer consumers access to lower-priced products, they also impact local businesses and take money out of a community. Both of these latter points have been affirmed by careful studies. A study conducted by Kenneth Stone, an Iowa State University economist, found that in the 10 years after a Wal-Mart opened, general-merchandise sales in Iowa towns with a Wal-Mart rose by 25% (mostly from Wal-Mart), while general-merchandise sales in surrounding towns dropped by 34%. During the same period, sales for both clothing stores and specialty stores dropped by 15% to 28% in both Wal-Mart towns and surrounding communities.2 Similarly, economic impact studies have found that a much lower percentage of money spent at a chain store stays in the local community opposed to money spent at a locally owned business. A study conducted in the Andersonville district of North Chicago found that $68 of every $100 spent at a local firm stayed in the Chicago area while only $43 of every $100 spent in a chain store stayed in the community.3

The upshot of this discussion is potentially heartening for prospective business owners. While the big-box retailers clearly win on price, and to lesser degree on selection, they are vulnerable on product quality, product knowledge, customer service, convenience, ties to the local community, and other variables. Because they can’t carry everything, they also leave gaps in the marketplace, providing the opportunity for other businesses to fill them. Luckily for new businesses, because the big-box retailers compete primarily at the low end of the market on price, the gaps they leave are generally at the high end of the market where profit margins are larger. Several of the businesses discussed in this book fit this description, including Wadee (handmade children’s toys), J.J. Creations (designer bags and backpacks), and Real Cosmetics (skin care products for women of all nationalities). These businesses sell higher-margin products that don’t fit the traditional product mix of a big-box retailer.

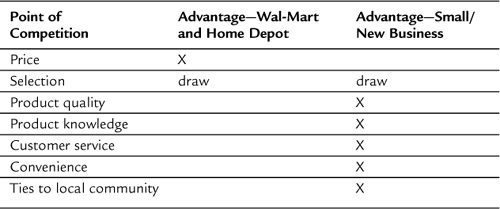

Table 6.1 illustrates the impact of this collection of insights on a potential new business. Imagine you are thinking about opening a nursery to sell plants, shrubs, trees, and lawn and garden supplies, but are hesitant to move forward because Wal-Mart and Home Depot are in your area and are selling similar products. Assuming that you’re knowledgeable, willing to provide a high level of customer service, willing to promote the idea that you’re a locally owned company, and otherwise capable of running a sound business, the checklist here shows the areas in which you can win and the areas that you’ll most likely lose in competition with Wal-Mart and Home Depot. As shown in the table, while Wal-Mart and Home Depot will invariably win on price and selection might be a draw, you can potentially win every other category (and serve customers that find these categories important). This is the general circumstance in which new firms and existing businesses compete successfully against big-box retailers.

Table 6.1. Garden Nursery Versus Wal-Mart and Home Depot

The next section of this chapter talks about the three most common approaches employed by small businesses to compete successfully against big-box retailers.

Approaches for Competing Successfully Against Big-Box Retailers

There are many lessons those wanting to start their own businesses can learn from existing firms about competing successfully against big-box retailers. The primary lesson is to take the threat seriously and not leave things to chance. If you plan to open a store or sell products or services that will compete directly against a big-box retailer, you should have an explicit strategy for dealing with the big-box threat. Small businesses don’t always do this. A pattern researchers have noticed in retailers that go out of business when a Wal-Mart or other big-box store comes to town is they don’t adjust their strategies. In fact, one study of 62 small retailers in southwestern Virginia found that 52% of store keepers didn’t adjust their product lineup, 42% didn’t adjust their pricing, and 21% didn’t adjust their service levels when a Wal-Mart opened in their area.

Another way of looking at the big-box phenomenon is that there are many businesses that it benefits. Local businesses often supply products and services to help the big-boxes operate. In addition, if your business offers a product line that complements rather than competes against a big-box retailer you might actually benefit by locating it in close proximity to the larger store. This strategy is pursued by Sally Beauty Supply, which appears in 26% of U.S. Wal-Mart anchored shopping centers. Explaining the rationale behind this strategy, Sally Beauty Supply spokeswoman Jan Roberts said:

"Wal-Mart generates an enormous amount of traffic, and we like to feed off that. We do have a few similar products, but we offer much more selection. If someone is looking for specific beauty items, we are more likely to have them...like the 400 (personal) appliances we carry, such as blow-dryers and curling irons."4

Now let’s look at the three most common approaches that small businesses utilize to compete against big-box retailers.

Operate in a Niche Market

As mentioned in Chapter 5, a niche market is a place within a larger market segment that represents a narrower group of customers with similar needs. It’s normally smart for a business that will compete against a big-box retailer to operate in a niche market so it can position itself as a "specialist" and provide a compelling reason for customers to shop at its store. This is what Sally Beauty Supply has done. It offers a very deep line of one product—beauty supplies. As a result of this singular focus, it can position itself as the "place to shop" for beauty supplies in a local community.

This same philosophy can be pursued in virtually any product category, as long as there are enough potential customers to support the business. An example is Paige’s Music in Indianapolis. The company, which has been in business since 1871, sells musical instruments to school bands and orchestras. The musical instrument industry is a tough industry, as mentioned in Chapter 5, and sales are down nationwide for a variety of reasons. Competition is also intense. Wal-Mart and Costco sell musical instruments, and there are several national musical instrument chains, including Guitar Center and Sam Ash Music. Despite these threats, Paige’s Music continues to grow, largely because of its laser focus on selling to school bands and orchestras, which is a niche market. "There are plenty of opportunities for the small local store to succeed against the big boys," says Mark Goff, owner and president of Paige’s Music, "but you’ve got to hit ’em where they ain’t."5 Paige’s primary market is the 400 school bands and orchestras in Indiana, along with the 36,000 students who are enrolled in music classes in Indiana schools. The store’s salespeople regularly call on the band and orchestra directors they sell to. This is a tactic that will most likely never be matched by Wal-Mart, Costco, or one of the national musical instrument chains.

If the business or store you’re contemplating will have some of the characteristics of a general merchandiser or category killer, you can still benefit by serving niche markets within the context of a larger business. For instance, in the example of the prospective nursery provided earlier, along with competing against Wal-Mart and Home Depot on factors other than price, the nursery could also become a specialist in one or more areas. For example, it might "specialize" in providing hedges, shrubbery, and sod for new construction and try to develop relationships with local builders and contractors. This is a niche market within the larger lawn and garden supply industry. It might also become the "place to go to" to purchase outdoor or indoor fountains. The overall point is that if the nursery couples its focus on the potential points of advantage along with becoming a specialist in one or two areas (while still selling its entire line of products), it will enhance its chances of success.

Differentiate

Once a business selects a niche market, it must differentiate itself from larger stores that sell similar products. Selecting a niche market, such as indoor and outdoor fountains or beauty supplies, is only the first step in separating your business from your larger rivals. The second step is to create meaningful forms of differentiation. Sally Beauty Supply relies on depth of product line and product knowledge as its forms of differentiation. Anyone who has shopped at Wal-Mart and Sally’s knows that Sally’s has a much broader and deeper line of beauty supplies. This doesn’t mean that everyone will buy their beauty supplies from Sally’s. But Sally’s provides people who want a larger selection of beauty supplies to choose from, a clear alternative to Wal-Mart. The biggest mistake that new firms and existing businesses make when trying to compete against big-box retailers is not drawing a sharp enough contrast between what they have to offer and what the big-box stores have. This notion is affirmed by Kenneth Stone, the Iowa State University economist mentioned earlier in the chapter. After spending 12 years studying the impact of the entry of Wal-Mart stores on small communities in Iowa, Stone concluded that businesses that adjusted and offered something different than Wal-Mart actually benefited from the spillover of additional traffic, while businesses that sold items similar to Wal-Mart lost sales unless they repositioned themselves.6

The primary thing to be mindful of in planning a differentiation strategy is the need to differentiate along lines that are important to customers. Apparently, depth of product line and product knowledge are important to Sally’s Beauty Supply customers, as evidenced by Sally’s success. Another example is Sam’s Wine & Spirits, a wine and liquor store that is sandwiched among a Costco, Cost Plus, Trader Joe’s, and Whole Foods in Chicago. To compete against its big-box rivals, Sam’s Wine & Spirits stresses customer service, product selection, product knowledge, and education. The education piece is the most interesting. To deepen its relationship with its customers, the company has created Sam’s Academy, which offers adult education classes (on wine and liquor), wine tasting experiences, and reward programs for repeat customers. Explaining the rationale for these initiatives, Brian Rosen, one of the business’s owners said, "(Wine) is a knowledge-driven subject, and people want to be educated." Again, the beauty of this form of differentiation is that it’s unlikely to be mimicked by one of Sam’s Wine & Spirit’s big-box rivals.

There are many other ways to differentiate a small business from larger rivals. Some businesses seek out employees who speak the language of their customers—literally. For example, Wheelworks, a large bicycle store in Belmont, Massachusetts (which is near Boston), employs people who speak Spanish, French, Italian, Chinese, and several other languages. This aspect of Wheelwork’s business fits the ethnically diverse nature of its community and provides it an advantage over stores that aren’t as sensitive to this issue. Other companies, like locally owned office supply stores, offer free delivery, day or night, which is something that a Costco, Office Max, or Staples is unlikely to do. Probably the most important form of differentiation is customer service. While almost all companies tout customer service as a point of differentiation, small businesses are able to deliver it in unique ways. For example, remembering the names of frequent customers, writing thank you notes for large orders, and knowing customers’ buying habits is something that small businesses are uniquely capable of doing.

One final note that is particularly encouraging for new or small businesses is that there is growing evidence that price, the factor the big-box retailers rely on the most, might be a fairly fragile form of differentiation. According to the Harvard Business Review, two-thirds of shoppers find the entire Wal-Mart shopping experience not worth the savings.7 A recent Wall Street Journal article affirmed this sentiment by reporting that specialty retailers across all segments are gaining on Wal-Mart despite Wal-Mart’s price advantages.8

Stress "Locally Owned"

A third approach that businesses use to compete successfully against big-box retailers is to stress the locally owned facet of their businesses (if they are locally-owned). This approach tugs at the heart strings of people who are loyal to their local communities and have a natural inclination to want to see local businesses succeed. The strategy is evident in signs that are placed in store windows or in ads that read "Locally Owned Business," "We Sell Locally Made Jewelry," or other similar comments. In fact, this type of strategy is much more than an advertising gimmick. One study of residents in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont found that 17% to 40% of consumers in each state were willing to pay two dollars more to buy a locally produced $5.00 food item.10 Similarly, a study by the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture found that "grown locally" ranked significantly higher than "organic" in regard to consumer preferences for fresh produce and meats.11

Stressing the local nature of a business can also be helpful in building its brand. Many states and regions of the country have placed labels on products originating from their geographic areas to draw attention to their wholesomeness and freshness. Examples include "Tennessee Pride," "Jersey Fresh," and "Iowa Beef." The subtle message conveyed by these labels is not only where the products come from but where they don’t come from. For example, most consumers would probably prefer "Alaskan Wild Salmon" to salmon advertised as coming from a densely populated fish farm in Chile (which is where most salmon in the United States comes from). While the Chilean salmon might be perfectly fine, the freshness factor and the U.S. roots of the Alaskan salmon are likely to give it a leg up for most American consumers.

The same philosophy can be applied at an individual business level. A locally owned business can tout the wholesomeness and freshness of its products (if applicable) as effectively as a region or state. It can also draw attention to the positive economic impact that locally owned businesses have on a community or local economy.

Specific Tactics That Local Businesses Use to Support Their Independent Status

There are a number of tactics that new and small businesses use to support the general approaches described here and to maintain their independently owned status. A tactic is a method employed to help achieve a certain goal. While most companies have similar broad strategic goals (increasing sales, increasing profits, producing quality products, behaving in an ethical manner, and so on), the ways in which they achieve their goals vary widely. The two tactics shown in the following sections are most applicable to businesses that plan to remain independently owned and are particularly concerned about competing against big-box retailers.

Partner with Other Small Businesses

A common tactic new businesses employ is to partner with other new or small businesses to increase their clout and buying power. Making this happen takes initiative and pre-planning on the part of a prospective business owner. He or she must get to know other business owners and establish relationships before the business is started.

There are several ways that small businesses can partner with one another in an effort to be as competitive in the marketplace as possible. One way is by joining or organizing buying groups or co-ops, where small businesses band together to attain volume discounts on products and services. An example is Intercounty Appliance, a buying co-op for 85 independent appliance stores in the Northeast. The co-op aggregates the purchasing power of its members to get volume discounts on appliances and other items such as flat-screen plasma TVs. An example of a much larger buying co-op is the Independent Pharmacy Cooperative, which was founded in Madison, Wisconsin in 1984. It has since grown into the nation’s largest purchase organization for independent pharmacies with over 3,200 member stores and is one of the major reasons that independent pharmacies are able to compete against Walgreens and CVS. There are similar buying co-ops in other industries. In many cases, the co-ops can get the same pricing on merchandise from a vendor as a big-box retailer. While belonging to a buying co-op doesn’t mean an independent firm will be able to compete against a big-box retailer on price, cutting costs on inventory provides the smaller firm with additional resources that can be used to invest in customer service and other forms of differentiation.

There are many other ways that small businesses partner with one another, from splitting the cost of a booth at a trade show to developing a joint advertising campaign. Many local businesses purchase their supplies and services from other local businesses rather than on the open market. This approach helps build camaraderie among locally owned firms and often encourages reciprocal buying and selling among locally owned companies. Big-box stores, which take their marching orders from corporate headquarters, are much less likely to engage in these types of activities.

Shop the Competition

A second tactic that new businesses utilize, particularly in the context of competing effectively against big-box retailers, is to shop the competition. The basic idea is that once a firm determines how it plans to compete against a larger rival, whether it is on product selection, product knowledge, or some other variable, it should continually assess whether it is maintaining the competitive edge it needs. In many instances, the only practical way to do this is to literally shop at the rival store.

Many business owners are transparent about how they go about this and will literally walk through a nearby Wal-Mart or Home Depot with a pad and pencil in hand. There are normally two objectives in mind when a person shops the competition. The first objective is to check on specific things like a competitor’s product selection and prices. The second objective is to view the competitor’s merchandise, get a sense of the general nature of the store, and get ideas that you might incorporate into your own store. There is nothing inherently unethical or improper about shopping at a rival’s store as long as you are honest and are observing things that are in the open. There are also less intrusive ways to shop the competition, such as looking at its Web site and monitoring its print and media ads.

Business owners vary regarding how bold they are when shopping the competition. Sam Walton was known for frequently visiting Kmart and Target stores during the years he was building Wal-Mart and was reportedly often seen making notes in a spiral notebook or talking into a tape recorder while in a competitor’s store.12 It occasionally irks the manager of a store to see a competitor walking his or her aisle, knowing that comparison shopping is taking place. Some managers see comparison shopping as snooping and actually ask competitors to leave their stores. More often than not, however, it’s a routine practice that doesn’t raise any eyebrows.

One particular advantage of shopping the competition is that it allows you and your employees to speak more authoritatively to your own customers. Imagine the following scenario: You are the owner of an independent appliance store that sells big screen TVs, which is a product that is one of your biggest money makers. A customer comes into your store with an ad for a 56-inch plasma TV for $2,200 from a big-box store. You sell flat-panel LCD TVs (which use a different technology) and have a 56-inch model for $2,500. Your exchange with the customer might go like this:

Customer:

"How does your 56-inch LCD TV compare to the 56-inch plasma TV I can buy down the street? Your TV is $300 higher."

You:

"Our TV is better," you say without hesitation.

Customer:

"How do you know it’s better? Have you seen the 56-inch plasma TV?"

You:

"No, I’ve never seen the 56-inch plasma TV, but I just know our LCD TV is better. Its brightness and sound quality are rated higher."

Customer:

"But you’ve never seen the difference with your own eyes? I don’t want to pay $300 more for the LCD TV unless it’s really better. It’s hard for me to see a difference."

You:

"Sorry, I’ve never actually seen the 56-inch plasma TV."

Not very impressive is it? It would have been much better if you could have said that you’ve seen the 56-inch plasma TV and then talk about your impressions of the differences between the two TVs. In addition, if you had shopped the competition thoroughly, there would probably be other things you could talk about. For example, if you know you have a cost and convenience advantage over your competitor in regard to delivery and installation, you might say, "Another thing to keep in mind is that the store that carries the plasma TV charges $200 for delivery and installation. We only charge $100. We also deliver and install on weekends and holidays."

Summary

Many small businesses compete effectively against big-box stores, primarily by operating in niche markets and differentiating themselves from what the big-boxes have to offer. There is no denying that the big-box stores are formidable. Stores like Wal-Mart and Target serve hundreds of thousands of customers daily and are growing in stature. But small businesses have an important role to play in the marketplace, too. The most important thing for a new business to understand is how to position itself in a way that avoids direct competition with big-box retailers.

The next chapter focuses on the myth that it’s almost impossible for a new business to get noticed. There are actually many ways for a new business to get noticed, but it takes some familiarity with the options and a willingness to persevere. Many business owners enjoy the process of spreading the word about the products or services they have to sell once they catch on to the most effective ways of going about it.

Endnotes

1. Gary McWilliams, "Wal-Mart Era Wanes Amid Big Shifts in Retail," The Wall Street Journal, October 3, 2007, A1.

2. Kenneth E. Stone, "Impact of the Wal-Mart Phenomenon on Rural Communities," in Proceedings of Increasing Understanding of Public Problems and Policies, 1997 (Chicago: Farm Foundation, 1998), Charts 5, 8, 9, and 11.

3. Andersonville Study home page, http://www.andersonvillestudy.com (accessed October 9, 2007).

4. Steve McLinden, "Who’s Afraid of the Giant?" Shopping Centers Today, June 2006, http://www.schostak.com/table_pages/images/shop_ctrs_today_art.pdf (accessed October 2, 2007).

5. Edward Iwata, "Companies Can Grow In Goliaths’ Shadows," USA Today, November 19, 2005.

6. Stone, "Impact of the Wal-Mart Phenomenon on Rural Communities."

7. Darrell K. Rigby and Dan Hass, "Outsmarting Wal-Mart," Harvard Business Review 12 (December 2004): 22, 26.

8. Gary McWilliams, "Wal-Mart Era Wanes Amid Big Shifts in Retail," The Wall Street Journal, October 3, 2007, A1.

9. B. Ruggiero, "Kazoo & Company Reaches Top 5...Again," TD Monthly, June 2005; J.M. Webb, "When the Tools of the Trade Are Toys," TD Monthly, March 2006.

10. Kelly L. Giraud, Craig A. Bond, and Jennifer J. Keeling, "Consumer Preferences for Locally Made Specialty Products Across Northern New England," (Department of Resource Economics and Development, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH), 20.

11. Giraud, Bond, and Keeling, "Consumer Preferences for Locally Made Specialty Products Across Northern New England," 4.

12. Sam Walton and John Huey, Sam Walton: Made In America (New York: Doubleday, 1992).