2. Becoming a Strategic Organization

“Adventure is just bad planning”

Roald Amundsen, Antarctic Explorer

“I may not have proved a great explorer, but we have done the greatest march ever made and come very near to great success.”

Robert Falcon Scott, Antarctic Explorer

Dr. Geoffrey Cromarty, Ed.D., is Vice President and Chief Operating Officer at Philadelphia University, where he has also served as Vice President of Planning and Institutional Research, Interim Dean of the School of Design and Engineering, and Executive Assistant to the President. At Philadelphia University, Cromarty led the University’s first strategic planning effort as well as the University’s master plan, landscape plan, and capital plans. He has worked at the University of Pennsylvania, Drew University, and the State of New Jersey. He has earned the Ed.D. and M.G.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and the B.A. from Western New England University.

Until 1911, the South Pole was still one of the last explored places on earth. The dramatic race to the pole ended on December 14, 1911, when a Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen, accomplished the goal, one month ahead of fabled British voyager Robert Falcon Scott, who died on his journey back, just 11 miles from his base camp. Amundsen’s success is not only one of endurance, but, most significant, one of intentional strategy and planning.1 Though Amundsen did not announce his intention to reach the pole until 1908, he began preparing and planning for the journey nearly a decade earlier, in 1899. Scott’s failure, however well-planned his attempt had been, was the result of poor implementation and the “Fallacy of Detachment.”2 Scott did not fully understand the environment and therefore failed to develop a plan that would enable him to succeed (or, in this case, live).

Becoming a successful, strategic organization, like polar exploration, also requires the strength and discipline to foray into areas outside comfort zones while respecting and understanding the environment, including history and competencies. Transformational success, however, takes place when the strategic plan supports the mission, it is intentional and flexible, and implementation is adaptable. Preparation, execution, and the ability to adapt have a critical impact on success and achievement.

Telling Stories

We learn best through stories. Storytelling is not a reliable strategy for transferring skills, but it is effective in sharing information that cognitive scientists say will be more memorable—and therefore more effective.3 In this chapter, our approach will be to use the Philadelphia University story as a tool for any organization to use in developing, refining, or improving their process—through either planning or implementation—to become a strategic organization.

A Model for Planning: Philadelphia University

Philadelphia University’s emergence as a strategic organization was born of necessity, change, and market demand. Higher education accreditation standards necessitated a strategic plan.

The reason for change was simple: a change in University leadership after the retirement of a longstanding president and the selection of a businessman/scholar who was committed to transforming an institution. He made it clear that strategic planning would be his first priority, and he wanted a plan that would honor the University’s past but propel it into greatness. Managing strategy, in higher education, government, or business, keeps the organization focused on key objectives and working toward their achievement, particularly in environments (most) with scarce resources. Leveraging resources toward strategic goals enhances the bottom line, whether it is education, services, or shareholder profit. It is critical, therefore, to develop a strategic plan that is supported and supportable.

Philadelphia University’s Planning Culture

Until that transition in 2007, Philadelphia University had thrived without a strategic plan. Created in 1884 as Philadelphia Textile School to educate America’s textile workers and managers, the College developed into a comprehensive university, granting bachelor’s and master’s degrees in professional fields, preparing professionals to be leaders in their chosen fields. It enjoyed demand for its diverse offerings, even in the crowded Philadelphia higher education marketplace; it had not needed a strategy to succeed.

For decades, planning at Philadelphia University meant facilities master planning. Campus facilities are important to traditional undergraduate students; the competition to develop better facilities has created an arms race among competing colleges and universities. The successful Disney organization sells experience through its theme parks, much the same way in which higher education sells education; facilities are a key component in delivering on the brand, though not necessarily the primary driver for consumer decision making.

The University had developed a series of increasingly sophisticated facilities plans to address pressing infrastructure needs. A handful, but representative group, of campus leaders organized the planning efforts. This planning history is common in higher education: In 1965, the Society of College and University Planners originally had primary interest in physical and facilities master plans.4 Integration of higher educational planning, to include budgeting and assessment, followed through the decades, becoming a requirement for college and university by accrediting bodies early in the twenty-first century. Likewise, corporate strategic planning, adopted from military planning, did not become prevalent until after World War II.

Toward the end of the long-standing president’s tenure in 2007, Philadelphia University began overtures toward a strategic plan by revising its mission statement5 through an informal process that allowed widespread input, but maintained control with the senior leadership. The president said, “It is healthy and constructive for any forward-thinking institution to revisit its mission statement, particularly as a tool for developing strategic, institutional goals.” The president invited comments from the campus community to get its feedback. The president then shared a draft with the campus and invited final input. The only comments were stylistic.

The campus community reaffirmed the mission: It remained unabashedly committed to preparing students for careers. The revised mission statement provided flexibility to grow, yet remained true to the University’s history and tradition. “In short,” the president said, “I believe this mission statement provides us with the tools to plan for student success.”

The commercial world offers many similar examples.

IBM was once International Business Machines:

• “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.” (Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, 1943)

• “IBM dreams of a computer in every home and every classroom.” (1974)

• IBM sells personal computer business to Lenovo, 2005.

Each statement was strategically sound in its time. IBM survived and even grew because it was willing to reexamine assumptions, question conclusions, and nimbly pivot to meet market needs.

IBM’s mission statement:

At IBM we strive to lead in the invention, development, and manufacture of the industry’s most advanced information technologies, including computer systems, software, storage systems, and microelectronics. We translate these technologies into value for our customers through our professional solutions and services and consulting businesses worldwide.

Google’s more succinct mission statement:

To make the world’s information universally accessible and useful.

In 2007, Apple dropped the word “Computer” from its name and became “Apple, Inc.” With a portfolio that spanned software, retail, online distribution of electronic media, home entertainment, cellphones, and computers, the name change was a subtle but clear signal that Apple would continue its relentless move into the wider field of consumer electronics.

An organization that is mission-driven is better prepared for change than one motivated by transactions.

Core Competencies

The Board of Trustees of Philadelphia University selected a new president in June. On his first day as the new president in September 2007, he immediately made the adoption of a strategic plan his top priority.

Developing a planning process for an institution that had no experience in strategic planning presented a challenge, yet it proved liberating because the University community had no tradition or allegiance to any planning process. The President’s Council explored step-by-step models,6 consulted with peer institutions, and researched planning methods to find a process that would create an implementable, measurable, and meaningful strategic plan. The new president, who spent more than a decade running a successfully franchised business, and another 14 years teaching entrepreneurship, brought discipline, expectations, and a demand for accountability to the process; however, he wanted the plan to be aspirational. Senior leadership adopted a vision for the plan: Create the model for professional university education in the twenty-first century. That bold statement guided all planning efforts.

The President’s Council identified three strategic areas on which a university-wide planning committee would focus—and created committees that would develop plans to support them:

1. Academic excellence

2. Excellence in the student experience

3. Alumni and community engagement

In essence, Philadelphia University was defining the required “core competencies” of the organization. C. K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel, in 1994 in their article “The Core Competence of the Corporation,” asked readers to think of a diversified organization as a tree: the trunk and major limbs as core products, smaller branches as business units, leaves and fruit as end products. Nourishing and stabilizing everything is the root system: core competencies.

To make the process transparent, the president invited the campus to volunteer or nominate someone to serve on a committee. Engaged stakeholders created a system of checks and balances and support; this approach also avoided the perception of a top-down plan from the new president. The Board provided input throughout the process. The planning structure was important. Broad participation can become endless debate. Input is good but decision making is essential. Representation, findings, and focus were channeled to a decision-making body.

The President’s Council worked with the chairs to identify the Strategic Planning Committee membership; it was a process intended to achieve balance and fairness—to ensure institutional perspective. Each of the committees had the responsibility to establish subcommittees based on the critical areas they identified. There were no constraints, but only the mandate, “Think big.” A Strategic planning website carried updates on the progress and substance of the planning process. Each committee approached its task differently: The Chairs managed the committees around their organizational and leadership strengths, not by a process dictated by success at other universities. A mission supported by core competencies was the common platform for planning. Committees were encouraged to be entrepreneurial.

Know Your Strengths

The University invited external academic consultants to initiate and guide the process. The president did not attend: “Presidents have a way of repressing the flow of ideas in the kind of setting [the consultants] have designed.”

The University developed a hybrid approach to traditional strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. At a retreat to begin the process, the consultants provided an overview of the state of higher education (opportunities and threats), and invited the attendees to begin thinking broadly about strategic issues. They asked for adjectives to describe the University (strengths and weaknesses), generated themes around the vision, and surveyed participants on “the University—the way we see it” and “the University—as it should be.” This exercise provided valuable data about perceptions and expectations. The participants developed themes that would guide the process. Importantly, the University conducted the “as is, should be” survey every other year for six years.

Integration

In developing initiatives, the committees first asked how the strategic goals would define the Philadelphia University experience. They considered the physical, financial, fundraising, technological, and human resources needed to implement the plan; they also looked for ways to integrate the objectives with those of other committees and developed initiatives that can be measured. In essence, the University was creating a business model.

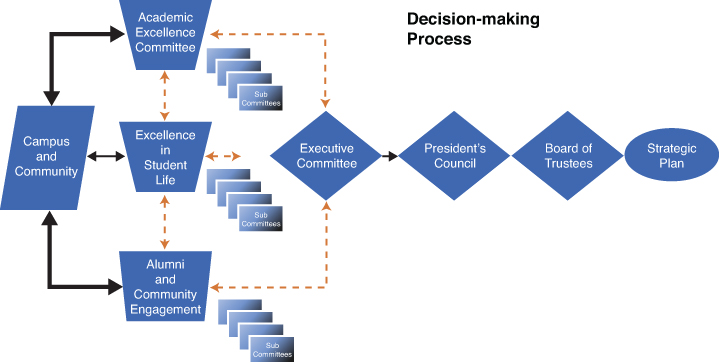

The subcommittees presented ideas from their deliberations to the relevant committee; the committee prioritized initiatives. Members of the three committees discussed these initiatives with the Executive Committee, which identified major themes for the committees to explore further and to integrate with other committees, as articulated in Figure 2.1. Critical to this process were the double-sided arrows, which mandated communication and integration by all the committees. Chairs and committee members evaluated initiatives from subcommittees looking for commonality and institutional priority.

The president allowed the process to evolve. He was a lively participant in Executive Committee meetings, pressing the Committee Chairs to bring initiatives that did not just improve the status quo but would differentiate the University—“add value”—and make the University the model for professional education in the twenty-first century. It was essential to make the University stretch; it was critical to honor the University’s history and strengths.

The subcommittees continued refining their goals with the guidance of the committees, while the Executive Committee directed the committees to work together closely to develop a far-reaching strategy. With a June Board of Trustees meeting scheduled to consider a draft of the strategic plan, the University scheduled a retreat to review the initiatives that had emerged so far.

Two of the themes that presented themselves at the January retreat—“signature” learning and interdisciplinary program opportunities—again rose to prominence at the retreat, to surprise and satisfaction.

The draft plan translated the concept of interdisciplinary learning to a practical “new” concept: the creation of the College of Business, Engineering, and Design—three schools together. One attendee, who had been skeptical about the process, believing there would be a top-down edict from a new, autocratic president, threw up her hands at the proposal. She finally had proof; the idea was a complete surprise to her and reflected nothing that she had heard in her committee.

A 41-year member of the faculty, who had seen more change at the University than anyone at the retreat, corrected the objector. She said that she had been collaborating with faculty from other schools her entire career. This proposal, she said, reflected the best, most active collaborations on campus and what industry sought in hiring employees.

The concept had support; the debate that followed focused not on whether it should be done, but on whether it would require an “über” dean to lead it. In the weeks ahead, University planners further developed the conceptual framework for what ultimately became the College of Design, Engineering, and Commerce, officially spawning the formalization of innovation.

The president shared with the Board of Trustees the draft plan in June 2008. The Board endorsed the concept of the College of Design, Engineering, and Commerce. Many were business leaders who saw the long-term benefit to job opportunities, growth, and innovation from people who could understand the realities of working in and among disciplines.

Throughout the summer, refinement of the initiatives continued; the Executive Committee drafted the plan for Board consideration in a meeting specially scheduled to adopt the University’s first strategic plan. The Board unanimously approved the historic document on October 2, 2008.

Absent from the initiatives are the kinds of insular plans of other, less strategic, plans, in which internal stakeholder interests are often included. Although those interests were well represented in the planning process, they were incorporated into the concepts that took shape into the broader university strategy. With so much involvement and communication in the planning process, it was clear to community members how initiatives that individuals proposed became incorporated into broader strategies.

Implementation Begins on Day One

The president used the adoption of the strategic plan as the platform for his inaugural address, which the University intentionally delayed for a year in the interest of preparing the strategic plan. Exhausted after a five-day celebration, the president welcomed the campus community on Monday morning with an e-mail, exhorting faculty and staff to begin implementing the strategic plan. The president called on his senior leadership team to develop a detailed implementation plan. He asked for a plan that would include champions, timelines, and measures of success. He asked that the document be made public and progress be reported quarterly to the Board. The objective was to transform planning into action.

Becoming a Strategic Organization

The planning, research, integration, communication, and structure of the strategic planning process created—and can create—a disciplined culture focused on goals and committed to achieving them, as depicted in Figure 2.2. The University leadership continued to show its resolve by taking actions to support the initiatives:

• Developed a budget process that rewarded new initiatives and encouraged reallocating funds in support of strategic plan initiatives, particularly those that resulted in collaboration among disciplines. To further support the process, the university created a budget advisory committee with university-wide representation that advised the CFO on budget priorities and communicated to university constituents.

• Began a process of “action research,” using tools from the first strategic planning retreat to monitor community perceptions about the University’s success in implementing the plan. Critical to this process was the action university leadership took in addressing the opportunities revealed in the data: When, for instance, the data suggested a lack of progress in advancing applied research, the president and others made personnel and funding changes to support the initiative. This process continued to keep the university focused on its core competencies and direction; the data provided valuable market data that enabled the university to respond.

• Initiated a comprehensive fundraising campaign to support the strategic plan. The strategic plan created the “case” for seeking outside investors/donors and further refined the narrative for communicating the message of the strategic plan; again, the fundraising campaign provided an opportunity for the university to tell its story in a memorable way. As a result, donors exceeded the ambitious goals of the campaign well ahead of schedule.

• Communicated frequently. By distributing laminated cards with the strategic initiatives, posters, and intentional, frequent formal and informal communications, leadership enabled the university community to understand the strategic plan and the direction of the university. Soon after the adoption of the strategic plan, one faculty member proposed a new academic program at a meeting of the faculty, making a strong case for support of the program with language in the strategic plan. Language is a powerful tool in shaping a culture and achieving success.

• Continued planning and implementing. By measurable, objective measures, the university had accomplished many of the goals in the strategic plan. Continuing to monitor progress and the external market, campus leaders developed a deeper understanding of where the overall strategy still needed support. The strategy was still critical; over five years of implementation, and with changing external market conditions, the tactics changed. The University developed a “Strategic Build” to continue with the strategy, but to pivot implementation in ways that would support the strategy better. Again, the University created a plan and funding priorities to support the initiatives of the Strategic Build, closing the circular process of renewal and growth.

Philadelphia University’s success in becoming a strategic organization is the result of hard work, discipline, and support, not by a few but by the organization. An organization can have success by knowing its strengths, developing an aspirational vision, gaining commitment to it, continually assessing the plan, supporting the plan with the budget, and changing the plan when conditions require.

Recommendations

Becoming a strategic organization requires an agile and nimble mindset, constant assessment and adjustment, and frequent refinements as conditions, inevitably, change. Specifically we recommend the following:

• Define what is important, possible, and consistent with your mission and vision. Be aspirational and intentional, but be honest and realistic.

• Allow input and delegate decision making; it builds consensus, ownership, and accountability—and results in success.

• Ensure open and constant communication; a well-informed community will be a supportive advocate.

• Test all assumptions: Ask, “So what?” when developing the plan. Ask, “So what else?” when implementing the plan. Assumptions must be translated into measurable goals in order to have an impact on success.

• Be prescriptive, but flexible: adapt the plan instead of forcing the goals, especially if they will not work; know your market and audience.

Endnotes

1. Roland Huntford, The Last Place on Earth (Random House Digital, Inc., 2007).

2. Henry Mintzberg. Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (SimonandSchuster.com, 1994).

3. Walter C. Swap, Dorothy A. Leonard, Mary Shields, and Lisa Abrams, “Using Mentoring and Storytelling to Transfer Knowledge in the Workplace,” Journal of Management Information Systems 18, no. 1 (2001).

4. Jeffrey Holmes, 20/20 Planning (Ann Arbor: Society for College and University Planning, 1985).

5. M. F. Middaugh, Planning and Assessment in Higher Education: Demonstrating Institutional Effectiveness (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2009).

6. Michael G. Dolence, Daniel J. Rowley, and Herman D. Lujan, Working Toward Strategic Change: A Step-by-Step Guide to the Planning Process (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1997).