7

Estimating the Work

Estimating. Nothing else symbolizes the challenges of project management better. Negotiate with senior management and customers to prevent “ball park” estimates from becoming your targets; team with subject matter experts (SMEs) and knowledge workers to develop accurate estimates for work that has never been done in these conditions, with these tools, by these people; assess your risks; educate stakeholders on the estimating process; and continuously manage the time-cost-quality equilibrium. Plus, you likely must do all of this in an organization that has not made the investment to improve estimating accuracy. Is it any wonder we love this job? For most people and most organizations, you would need a moving truck to carry all the baggage that comes along for the ride when estimating is discussed.

The baggage accumulates from political battles, misunderstandings, a sense of no control, and past troubled projects. As a result, there are complete educational courses and books in the marketplace that cover nothing but estimating—not to mention the many reputable therapists that can improve your emotional and spiritual well-being (just kidding; it’s not that bad).

This chapter shows you how to leave that moving truck behind and take control of the estimating process. It can be done. First, we review how estimating the work fits in with the overall schedule development process and how it is an integral part of how we manage risk on the project. Then, we examine the key estimating techniques and methods and how to use them. And finally, we discuss the common reasons for poor estimates and review the golden guidelines of estimating. This will enable you to improve your estimating accuracy and get it right the first time.

Next Step in the Schedule Development Process

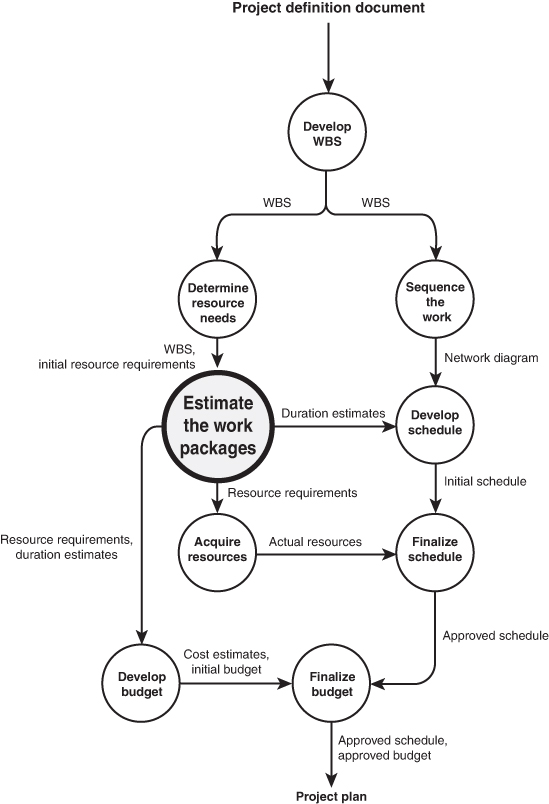

Before we get into the details of estimating, let’s make sure we are clear on where estimating falls in the schedule development and planning process. If someone stopped you on the street and asked you for an estimate, what is the minimum information that you would need? You would need to know what the estimate is for—what work is to be done. And you would need to know who is going to do it—what type of resources will be involved in performing the work. This flow is shown in Figure 7.1. Estimating the work should occur after you have identified the work and after you have thought about what resources are needed for the project.

FIGURE 7.1

The step of estimating the work in the development of the project schedule.

It sounds so simple, doesn’t it? Then why is this so tough? Well, we cover this in more detail later in this chapter, but these two basic prerequisites are where most estimating woes originate. There is often not a clear or complete understanding of the work to be performed by the person doing the estimate, and the relationship between the work estimate and the resource doing the work is not defined or communicated. In addition, there is the challenge of estimating work that has not been done before in exactly these conditions.

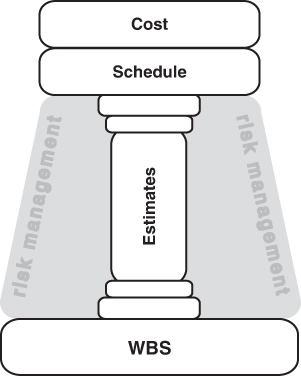

Yet, estimating the work effort is a cornerstone activity for planning the project. From these work estimates, we determine the project costs (see Chapter 9, “Determining the Project Budget”), develop the project schedule (Chapter 8, “Developing the Project Schedule”), and identify key project risks. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 7.2.

FIGURE 7.2

The foundational role that the WBS and the work estimates play in the overall planning process.

Managing the Risk, Managing the Estimates

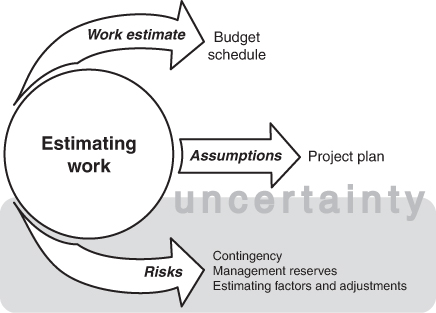

There lies the key challenge. How do you manage the uncertainty that is naturally involved with the estimating process? Because these estimates form the foundation for the project schedule and the project budget, you must implement techniques and approaches that enable you to properly manage this risk and the expectations of your stakeholders.

Although this subject of estimating and risk could easily slip into a review of statistics, probability, standard deviations, skewed distributions, and Monte Carlo analysis, we will not go there. In many real-world environments, these advanced concepts and techniques are not utilized to estimate work and to manage the associated risk, and these topics would be outside the scope of this book. Our focus is understanding the impact that estimating work has on our overall risk management approach and what we can do to minimize those risks.

Estimating the work is a fundamental risk analysis step. Not only do you estimate work efforts, but you also identify the assumptions that support the estimate and the key risk factors that might affect the accuracy of those estimates. These key outputs are depicted in Figure 7.3.

FIGURE 7.3

Estimates are key inputs for scheduling, budgeting, and risk management.

Reasons for Estimating Woes

Before we review the key estimating techniques and methods that we need to know to best plan our projects and manage our risk, let’s first take a deeper look at the common reasons for estimating woes on many troubled projects:

Improper work definition—The number one reason for inaccurate work estimates is inadequate definition of the work to be performed. This includes the following:

Estimates based on high-level or incomplete requirements.

Estimates based on incomplete work—work elements (packages) not accounted for in the WBS.

Estimates based on lack of detailed work breakdown.

Estimates made without understanding the standards, quality levels, and completion criteria for the work package.

Wrong people estimating—Another key reason for inaccurate work estimates is that the wrong people make the estimates. Although it might be appropriate for management to make ballpark estimates during the early defining and planning stages, when firm commitments must be made, it is best to have the people who have experience doing the work make the estimates (or at least review and approve any proposed estimate made by someone else).

Poor communications—This reason hits on the process of facilitating estimate development. This category includes events such as

Not sharing all necessary information with the estimator.

Not verifying with the estimator what resource assumptions and other factors the estimates are based on.

Not capturing and communicating the estimate assumptions to all stakeholders.

Wrong technique used—We cover this in greater detail in the next section, but this category includes events such as

Making firm budget commitments based on top-down or ballpark estimates rather than bottom-up estimates.

Not asking for an estimate range or multiple estimates.

Not leveraging the project team.

Not basing estimates on similar experiences.

Resource issues—This is a specific case where it’s not really an estimate issue but an issue with the assumptions supporting the estimate. This is when the person assigned to do the work is not producing at the targeted level or when there are performance quality issues with any of the materials, facilities, or tools. Without documented assumptions, these issues can appear as inaccurate estimates to stakeholders.

Lack of contingency—In many cases, especially on projects involving new technologies and new processes, the identified risk factors are not properly accounted for in the work estimates. The uncertainty level in specific work estimates needs to be identified and carried forward into the project schedule and budget as part of the contingency buffer or management reserve.

Management decisions—In many situations, senior management influence and decisions impact the estimating accuracy level. This category includes events such as

Senior management making firm budget commitments based on initial, high-level estimates and not accounting for accuracy ranges.

Senior management not willing to invest time or resources to get detailed, bottom-up estimates.

Estimators factoring their estimates for senior management expectations rather than the actual work effort.

Management requesting that estimates be reduced to make the work meet the budget or schedule goals.

Management decisions to bid or accept work for less than estimated cost.

No use of management reserve to account for risk or uncertainty.

Powerful Estimating Techniques and Methods

There are several key estimating techniques you should know about. Table 7.1 lists these techniques and summarizes the key characteristics of each.

TABLE 7.1 Estimating Techniques

Estimating Technique | Key Characteristics | Notes |

|---|---|---|

Analogous (top-down) estimating | Used in early planning phases and project selection. Utilizes historical information (actual duration periods from previous projects) to form estimates. | Reliable if WBS from previous projects mirror the WBS needed for this project. |

Bottom-up estimating | Used to develop detailed estimates. Provides estimate for lowest level of the WBS (work package). Provides the most accuracy. | Best technique for identifying risk factors. Takes most time and money to develop. |

Effort distribution estimating | Uses project phase percentages to estimate. Example would be Initiation Phase—10% Plan Phase—10% Elaboration Phase—20% Construction Phase—40% Deploy Phase—20% | Used in organizations that use common methodology and/or that do similar projects. Can be used if enough information is known for one of the major project phases. |

Heuristic estimating | Based on experiences. “Rule-of-thumb” estimating. Frequently used when no historical records are available. | Also known as Delphi technique and expert judgment. |

Parametric estimating | Uses historical data and statistical relationships. Developed by identifying the number of work units and the duration/effort per work unit. Examples include the following: Lines of code for software development. Square footage for construction. Number of sites for network migration. | Also known as quantitative-based estimating. Can be used with other techniques and methods. |

Phased estimating | Estimates the project phase by phase. Provides for a detailed, bottom-up estimate for the next phase and a higher level, top-down estimate for the other phases. Best technique to use on high-risk and agile projects. | Incorporates “re-estimating” as part of the management approach. Best use of estimating resources. Excellent risk management tool. |

For each estimating technique (approach), there are one or more methods that can be leveraged. Table 7.2 lists these methods and summarizes the key characteristics of each.

TABLE 7.2 Estimating Methods

Estimating Method | Key Characteristics | Notes |

|---|---|---|

Expert judgment | Relies on SME in targeted work area. | Used most effectively with bottom-up estimating. |

Historical information | Relies on actual durations from past projects. The three types are project files, commercial databases, and project team members. | Many organizations do not accurately capture this information. Recollection of project team members is the least reliable source. Critical to improving estimate accuracy in an organization. |

Weighted average (PERT) | Uses three estimates for each activity (weighted average): optimistic, most likely, pessimistic E = (O + 4M + P) / 6 Each estimate is captured for each activity. | Used mainly on large-scale or high-risk projects. Excellent risk management technique. This technique is time consuming. PERT = Program Evaluation and Review Technique. |

Risk factors | Adjusting an original estimate based on one or more risk factors. Used in conjunction with other methods. | Common risk factors affecting effort estimates include complexity (technical, process), organizational change impact, requirements (volatility, quality), and resources (skills, costs, and so on). |

Team (consensus) estimating | Uses multiple SMEs to develop independent estimates. Facilitation meeting used to reconcile differences and develop consensus estimates. | Best for identifying assumptions and other risk factors. Avoids one person being accountable for estimate. Allows for multiple historical perspectives to be taken into account. Allows SMEs from different backgrounds to complement one another. |

As with all other planning activities, work estimates are refined and improved as more is learned about the project. At a minimum, each project (or project phase) should be estimated three times. Each estimate provides a greater degree of accuracy. To better understand this concept and to better educate others in your organization, see the three levels of estimate accuracy recognized by PMI in Table 7.3.

TABLE 7.3 Estimate Accuracy Levels

Level | Accuracy Range | Generally Used During |

|---|---|---|

Order of magnitude | –25% to +75% | Initiating (defining) phase |

Budget | –10% to +25% | Planning phase |

Definitive | –5% to +10% | Planning phase |

Best Practices

Now that we have an overview of the estimating techniques and methods that are available to us, and we have a feel for the estimating mistakes that are commonly made, let’s review the estimating best practices of successful organizations and projects:

Should be based on the work breakdown detailed in the WBS.

Estimating should be performed (or approved) by the person doing the work.

The work estimates for lower-level WBS items should be less than the standard reporting period for the project (typically one or two weeks).

As discussed in Chapter 6, “Developing the Work Breakdown Structure,” if the work estimate is not less than this, it is a good sign the task needs further decomposition.

Estimating should be based on historical information and expert judgment.

Estimates are influenced by the capabilities of the resources (human and materials) allocated to the activity.

Estimates are influenced by the known project risks and should be adjusted accordingly to account for those risks.

When estimating effort for something unprecedented or high risk, where the confidence level in any estimate is low, leverage timeboxing and proof-of-concept models to improve knowledge quickly, so you can derive better estimates. This approach is a key aspect of agile projects.

All bases and assumptions used in estimating should be documented in the project plan.

When asking an SME for an activity estimate, make sure to provide the following whenever possible:

Project definition document (context, approach, assumptions, and constraints)

WBS

Applicable standards, quality levels, and completion criteria for the work package

When asking an SME for an activity estimate, make sure to ask for the following at a minimum:

An estimate range (not just a single value)

Factors driving that range

Assumed resource level, skills, and productivity

Assumed quality level and acceptable completion criteria

Estimates should be given in specific time ranges.

To manage high-risk projects, the following estimating techniques are recommended:

Use of phased and bottom-up estimating techniques

Use of the average weight and team consensus estimating methods

For high-risk projects where the organization lacks significant previous experience or process knowledge, consider outsourcing the planning phase to an outside firm as an assessment engagement.

A project’s time and cost estimates should be based on project needs and not dictated by senior management. The project manager should work with senior management to reconcile any differences.

Reserve time (contingency and buffer) should be added to either the project schedule or to individual activity duration estimates to account for the level of risk and any uncertainty that exists.

Historical information is vital to improving estimates. If you don’t measure actual performance, you will not have the feedback to improve estimating accuracy.

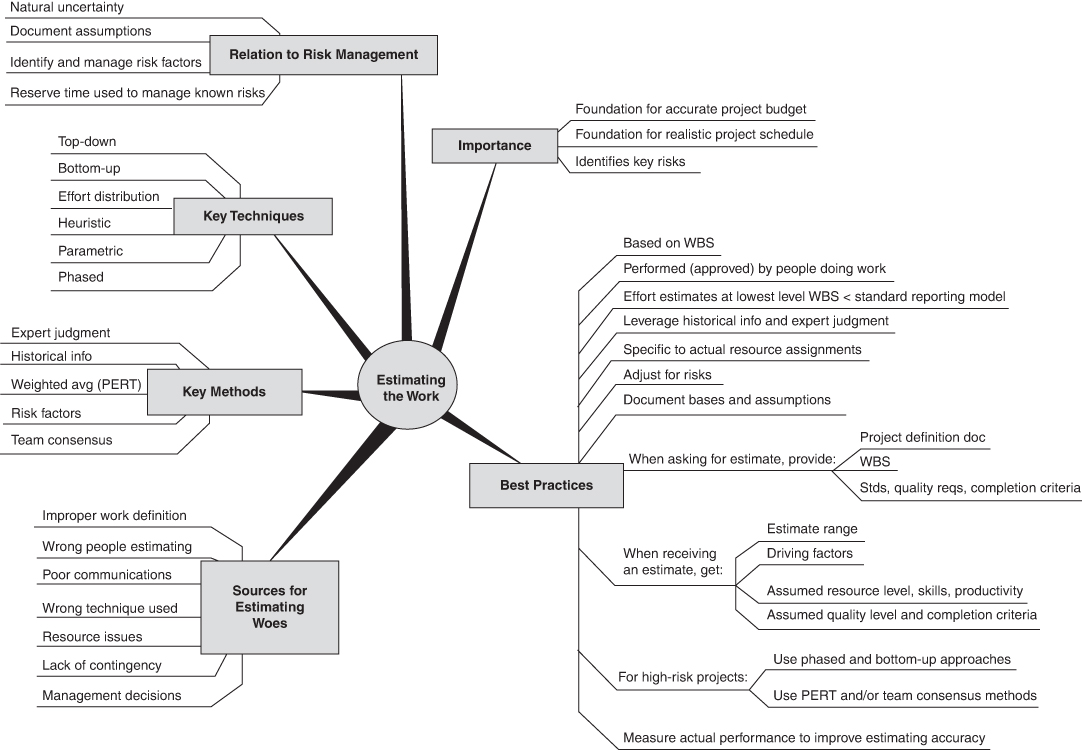

The map in Figure 7.4 summarizes the main points reviewed in this chapter.

FIGURE 7.4

Estimating the work overview.