Chapter eight

Being and becoming masterful

•••

Now we will explore the nature of masterful coaching practice and the experience of being, play, not knowing, impartiality, holding and flow. Also, how the faculties of intention, intuition, imagination and integrity emerge together with qualities such as compassion to inform the presence of the masterful coach.

•••

We seem to look everywhere else for the key to mastery except in our own hands.

You and no one else hold the key to your masterful practice right here, right now; the master key is already in your hands

• Ending the search •

The more we try to coach, the less our success. Mastery is found when you realise that there is nothing more you need to find. Mastery is the confidence and self-reliance that you discover when you place your trust in your own natural and innate ability to coach. When you permit yourself the freedom of not striving, you can begin to experience and enjoy these talents and discover and employ the essential inner toolkit of the masterful coach.

It is a fascinating revelation to the coach that we can spend our whole lives searching for mastery, only to realise that being masterful is the natural consequence of ending our need to search.

• Accepting fallibility •

To end your need to search and start your progress to mastery, there are certain things you must allow yourself to be, or allow into your life, and being fallible is one of them.

While writing this book I accepted an opportunity to teach a group of counsellors and psychotherapists who wished to explore coaching practice. The details of this workshop, which was to run over three months, were set and advertised.

One morning, out of the blue (or so I thought), the course director called. He asked very anxiously, ‘Where are you?’ ‘At home’, I replied. A part of me froze with his next comment: ‘Andrew, your students are waiting for you!’

To my horror I had by mistake put the wrong date in my diary and the course had started without me! My students were waiting and some had travelled long distances to attend. On a scale of 1 to 10 of nightmare situations, I experienced this to be about an 8.

We worked out a strategy where the director would ask the students whether they were willing to start the course the following day. If so, I would drive to London immediately. As I put the phone down, I started a process of self-reproach and felt simply mortified by my error. I couldn’t quite believe how I had got this so wrong.

The director returned thirty minutes later to say that all the students were willing to begin the course the next day. So my journey down to London began. Only when I was in my car and breathing more deeply did I begin to reflect and consider what might be happening.

Over twenty years of coaching, I could not recall missing an appointment and yet I had got this date completely wrong. Might this error in some way be important and could it inform my teaching of the course?

The next morning I woke very early, to be absolutely sure that I would be there on time. The moment arrived when my participants entered the room. I started:

Let me begin by saying how truly, truly sorry I am about yesterday. It was entirely my error and I realise that I left you stranded here as a result. I am truly sorry about that and I am grateful for your willingness and flexibility to work today and tomorrow. When I realised my mistake, I was over four hours’ drive away. Once more, please accept my sincere apology.

I took time to explore how my absence had impacted each person and then turned to the group and expressed clearly:

This experience has brought me in close touch with my own fallibility. I wonder how important fallibility is to the work of the coach? Might we consider this as an important context to the course over the next three months, since its presence is so visible as we begin?

And so we did, and what an insightful context it turned out to be.

We drew the illuminating conclusion together:

When we accept our fallibility, our limitation, our imperfection, we no longer strive to become someone other than our most natural self. We are free and can relax into the discovery of a deeper centre of identity – the original self – and it is there that we can meet with the masterful coach.

Fallibility takes comfort in imperfection and finds joy and wonder in the ordinary. Acceptance is the key that can unlock and free your mastery.

Maybe the masterful coach is your most authentic identity as a human being

Fallibility and the organisational coach

The permission to be fallible may at first seem at odds with the demands of high-level business. The need of organisations is for employees to access more of their hidden potential and resourcefulness to become increasingly productive – often I will hear the leadership message, ‘We need to do more with the same or less’. Underlying this message is a fear of making mistakes. Mistakes are no longer permitted. But being infallible and not being permitted mistakes are inconceivable. Only when we accept our fallibility does striving end and a door inwardly open, through which we can explore and access our inner resourcefulness and so help others to do the same.

We can now see how the invincible and infallible analytical eye imprisons its own potential and creative possibility. Only when the analytical aspect is combined with the appreciative to form the creative eye can it see beyond its own blindness. This is the way we can unlock the unlimited potential of the masterful coach.

Pause point

Consider the consequences of accepting your fallibility as a coach. How does your fallibility actually inform your practice?

• Experience of mastery •

How can we describe and discern mastery? I think of mastery as something similar to discovering a secret recipe. We suddenly realise the vital ingredients that combine together to offer masterful practice.

Being

We have already considered how, in striving continually to get somewhere else or to be someone else, we create the experience of an isolated, partial and incomplete self. The masterful coach realises that, in searching for something more outside ourselves, we lose sight of something vital within – the source from which our power to change originates. When we can end our need to search, we realise the full possibility and prospect of the present moment.

In striving to remember the past or visioning the possibility of the future, we actually lose our concentration and attentiveness, and the present moment can pass us by. The present moment is the only place we can change; past and future are virtual realities. We cannot choose from any other place but the present moment. In fact, this is all we ever have – I think of it sometimes as my ever-present now.

For the masterful coach, every moment is fulfilling and a destiny in itself. Making each moment a destiny in itself, we focus our vision on the here and now. What we learn is how to savour and notice things that previously we would have missed. We become the most attentive, playful and deeply caring observer, a lover of watching and listening. When we surrender our need to be someone else or somewhere else, we begin to remember the original self and recognise the true identity of the masterful coach.

Play

Have you noticed how the best questions seem to be asked by children, with their endless curiosity about themselves and the world around? A child is spontaneous and has no uneasy hesitation; questions are asked openly and honestly. Children have a freedom that is commonly lost to the adult. Their creativity is unbounded and a joy to observe.

My great niece Millie came to my house to play. Millie is six years old. While we were in the garden, Millie decided to dance and sing me a song. She took hold of the sweeping brush as a microphone and proceeded to dance and sing (her own composition) on the theme of tulips.

I was astonished and marvelled at her creativity, sense of freedom and enjoyment. There was no hesitation with words or rhymes, everything just flowed. She danced freely as she sang, loving the whole experience. I noted how endearing she was in her sense of freedom and play. Through her rendition I reconnected with the importance of the child to the work of the masterful coach. The coach can learn a great deal from children and, in the course of the coaching journey, I believe we often do.

When I coach I am often reminded of the child within me, who is keen to play and be free, inviting me to share in this experience. This is not a childish presence. Through the innocent eyes of my child I seem to see the world afresh. My sense of humour and fun are awakened, and there is endless curiosity and questioning. No question in fact seems out of bounds, and I feel a sense of wonder. I can more deeply appreciate the beauty of ordinary things. I am often spontaneous and highly intuitive.

Pause point

Imagine the value of the child to your work as a coach. Do you ever free the child when you practise?

The freedom, curiosity and playfulness of the child are important traits associated with the discovery of the masterful coach

My playful child and compassionate adult can be a very powerful and insightful partnership. When I coach I can give challenging feedback with humour, honesty, care and a lightness of touch. Let me share a few recent examples from my own coaching practice.

The adult can often have a great hesitancy around what one should do, or must do, that is absent from the child. When I coach, mindful of the child and the importance of play, I seize that endearing honesty and playfulness and often feel inspired to act in the moment.

I was working recently in a group supervision setting with a number of coaches. I realised that one member of the group, Paul, was dominant and a little intimidating. I wondered how this aspect of Paul’s persona might influence his coaching relationships. While working with the group, I suddenly turned to Paul.

Coach: | Paul, do you know you are a bit scary (laughing)? Has anyone ever told you that before (laughing)? |

Paul: | (Laughing also) No, am I really? |

Coach: | Yes, just a touch, just a smidgen. |

I feel playful and quite spontaneous in giving this important feedback. John, another member of the group, intervenes.

John: |

You are a bit (smiling). |

Paul: | I didn’t realise. Might I scare my clients? |

Coach: | You might, I don’t know (smiling). What do you think? |

Paul: | I need to explore this, I think. |

Coach: | Good. We can let you know if we experience you as scary, if that would help, can’t we folks? This may help you to get to know that part of yourself a little better – more consciously maybe. Does that work for you? |

Paul: | Yes that would be helpful. |

Paul did some good work getting to know this dominant characteristic of his persona. As he recognised this aspect, the group observed and mirrored how Paul’s persona softened.

Not knowing

We seem to believe that life is a search for the answer and yet the single most important revelation leading to the discovery of the masterful coach is how, in cultivating the capacity to not know, we can remember our motivation to change and realise our creative potential and possibility.

The masterful coach is quite comfortable in not having to know the answer. Normally this experience of not knowing causes anxiety, fear and sometimes panic. From my experience, our capacity for not knowing is key to development and growth. Paradoxically, not knowing provides the client with the chance to expand awareness, discover new choices and accept creative insights. In the coaching relationship, the client can practise not knowing with someone trustworthy. This is a vital opportunity for learning and growth.

By being present to another, to walk beside or guide someone else, to truly help another to develop and grow, we are invited to let go of knowing and having the answer.

It is a courageous act to share not knowing with someone else to help them to rediscover their desire to change and grow

It is an act of faith where we decide to get lost together, trusting that the answer will emerge from within through the courage and freedom of not having to know.

In Chapter 7 we explored the different roles of the coach, and one in particular again comes to mind – the wayfarer. When you coach you take an adventure with someone else – you decide to enter into the unknown in order to potentially help another to grow. The masterful coach is certainly a wayfarer: someone who is willing to enter wholeheartedly into the adventure of not knowing, paradoxically in order to know something more about the generative nature of self and the coaching relationship. In our willingness to explore, we help our clients to forget who they think they are and instead discover who they might truly be.

• Impartiality •

Most of the case studies I have included show how we and our clients commonly get stuck and are unable to choose a way forward. We somehow get caught in the duality we create. The masterful coach can clearly see and yet not react to division, duality and difference. This parallels the ability of the coach to accommodate the paradoxical nature of reality. Let us explore in more detail what I mean by this.

The masterful eye is an impartial eye. It can look at either this or that and consider the pros and cons. It can also see, sense and articulate a deeper, often hidden, relationship between apparently contradictory elements. This offers the masterful coach the rare ability to contextualise. The vision of the masterful coach can sometimes see and conceive of the larger whole in which the client’s experience is a part. It is the work of the masterful coach to conceive and discover these larger contexts to offer the clients the chance to understand more deeply their apparent dilemma, to make meaning of their journey, and to grow.

When I coach, I gradually see how a client may be limiting their vision and potential by judging and dividing – wanting either this or that. I will often smile and plant the seed: ‘Have you considered if you might be able to have it all?’ Providing the larger context – naming the paradox and reframing the current situation and scenario – is once more not about giving the client the answer. Instead, it helps the client to see the potential and possibility within the present moment. In realising our potentiality we remember our innate mobility and desire to change.

When I plant seeds it is an invitation to the client to discover, through the shared eyes of the coaching relationship, a larger context that may bring learning, development and meaning to their journey. This essentially provides an opportunity for the client to step beyond division and conflict to consider if there is a deeper, more creative and meaningful resolution. In discovering the masterful coach we can help the client to step out of conflict and reconnect with their innate desire to change and grow.

The coach reminds the client of their potentiality and can transform a sense of ‘feeling stuck’ into the prospect of mobility and desired change

Let me demonstrate what I mean by recalling an earlier case study.

Susan, you may remember, has a dilemma of ‘being’ and ‘doing’. Susan’s temptation was to split these twins and to focus on either being or doing. Having weighed up both, her favoured choice was doing, because this allowed her the joy of activity. Her moment of realisation happened when the seed was planted that she might be able to ‘have it all’ – was there value and meaning in considering how her being may exist at all times within her doing?

Like the eye of a storm, do we find stillness within each busy moment? Rather than split, Susan was able to embrace her paradoxical nature – the being in her doing – and see the value and learning opportunity presented by this larger context. Her learning strongly influenced and informed her coaching practice as well as her personal development.

When we discover the masterful coach we can operate from a place within that is beyond duality and conflict. From this platform, rather than react to division and difference, the coach can offer the client impartiality – the unconditional opportunity to meet with and consider both sides equally. This allows the client to look beneath and beyond the immediate challenge to discover whether a deeper, more peaceful, resolution exists. It opens the possibility that if we can see past the temptation to judge and split, we can discover new potentiality and the prospect for growth. Through the shared eye of the masterful coach, apparent problems can transform into opportunities for development and growth, and provide the chance to discover a deeper and more meaningful context to our life and work.

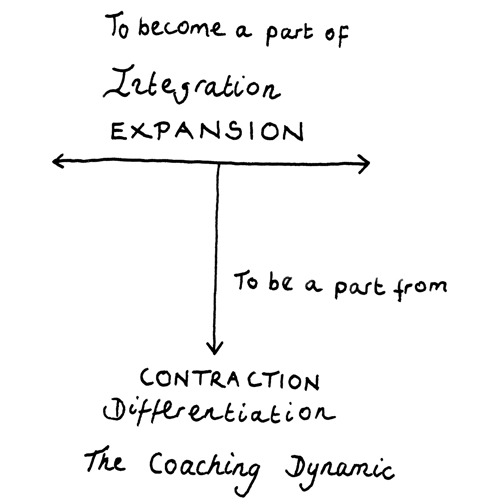

The masterful coach reminds the client of the dynamic relationship and potentiality that can be realised by acknowledging our partial wholeness. We are singular in seeking to differentiate and see ourselves as distinct – apart from others. We are also plural in ever seeking to find our place and belonging – a part of something larger. This defines our innate and dynamic potentiality that motivates change (see Figure 18, opposite).

Figure 18

• Holding •

In moments of mastery we also discover a quality of holding. This is a capacity of the coach to recognise an aspect of which the client is unaware, and to purposefully hold this new awareness until the client is ready and able to accept it. The masterful coach knows the importance of timing and will consciously hold certain aspects of this potential gift until the time is right to share. Let me use a recent case study to illustrate this holding capacity.

Pat, a senior scientist and physician, was badly affected by profound organisational changes and a shifting role. Part of her behaviour showed a critical mistrust of authority. When working with Pat, I chose to hold a particular piece of what I considered to be vital feedback for some months, until Pat was in a more generative and stable place, and was able to receive and work with this feedback. Consider the following extracts from my coaching conversation:

Coach: | How are you now, Pat? |

Pat: | Better, more stable and engaging a little more. |

Coach: | On a scale of 1 to 10, where are you in your satisfaction with your current role? |

You asked me this last time and it was 2 or 3– now it’s 5 or 6. | |

Coach: | (We smile) What’s changed? |

Pat: | I have (pause)… I feel with your help – I am more in control of my destiny. |

Coach: | Are you in a good place to progress the coaching work? |

Pat: | (Laughs) Yes. |

Coach: | How do you feel about your boss or bosses now? |

Pat: | I am beginning to engage more, but still keep on the edge. |

Coach: | Is it safer there? |

Pat: | Yes. I’m critical of strategy and don’t fully buy in, so I don’t fully engage. |

Coach: | Good awareness. So you avoid fully engaging and step out of relationship? |

Pat: | Yes. |

Coach: | That keeps you safe? |

Pat: | Yes. |

Coach: | But you don’t engage fully? |

Pat: | No. |

Coach: | Do you make a choice? |

Pat: | No. I don’t fully commit. |

Coach: | How does this limit you, Pat? |

Pat: | (Pause) I’m never fully committed (pause) or a part of anything really. |

Coach: | There’s something I want to bring to your attention. |

I have checked in with myself and the time feels right to share back with Pat something that I have been holding for a while – the potential saboteur.

Yes? | |

Coach: | Are you sabotaging something here? In keeping yourself safe, are you losing something quite precious? |

Pat: | (Long pause) Mmm. I’m setting this up, aren’t I? |

Coach: | Say more. |

Pat: | In not trusting, I think I do sabotage getting more involved and being a part of something – influencing things. |

Pat: | Excellent Pat, your awareness is spot on. You appear to have a saboteur protector. |

The saboteur is made conscious and given back into Pat’s care. I am delighted to see how much Pat is gaining insight and awareness, and am keen to give her encouragement.

Pat: | That’s useful. I am creating the same old sequence, aren’t I, then blaming it on bad leadership? |

Coach: | The leadership may play their part and, yes, you may be recreating something. What about the chance for you to shape your ideal job? Do you have a choice? If you’re not engaged and willing to consider and value your own needs, how can you shape and potentially influence your future and your occupation? |

This feels generative, so I explore how willing Pat may be to work with her choice and be able to shape her ideal role/occupation.

Pat: | (Long pause) I hadn’t realised how much I have been limiting myself and that I have a choice to make it different. |

You can change that now, if you desire? | |

Pat: | Yes (pause), I think it’s the right time. |

The capacity to hold in this way is essential to the work of the coach. If we return to the coaching jigsaw analogy, we are making conscious and giving to the client what may be an important piece of the jigsaw that has been held in our care that may help to complete a section and resolve the puzzle – we are giving this back to the client as a gift.

The coach is effectively helping the client to come to know and accept different aspects of their personality. Authenticity can deepen as a result. After being quite traumatised by a sequence of events and dramatic change, Pat was now reflecting more deeply. She was expressing how her own psychological process was serving and limiting her work, becoming more honest with herself and realising her desire to change.

• Flow •

When we discover the masterful coach we realise the paradox that mobility is the natural consequence of being and becoming still.

The activity of masterful coaching does not deplete energy but revitalises. When we discover the masterful coach and allow this presence to guide our coaching, we do not tire of practice and our energy levels remain topped up. Mastery happens when we realign with a centre and source of our potential for development and learning. We make the discovery of original self and recomplete a circuit whereby our hidden potential becomes available as power. This we experience as being in flow. As we return to our original nature we discover an innate energy – a will that literally moves us. We are inspired to respond spontaneously from the inside out.

The masterful coach can purely focus their attention on the activity of coaching. The activity is fulfilling in itself and serves no other purpose. The quality of relationship between coach and client naturally deepens. The prospect of flow becomes potentially available to the client, as both the client and the coach share the same energy field.

Two of my clients have described the experience of being in flow in coaching sessions. In order to ground learning and harness the potential value, I asked if they would describe this experience in words. Here are extracts taken from both transcripts that, I believe, help to illuminate the experience of being in flow and how this relates to mastery.

Ben is an experienced coach in supervision:

My experience of being in flow is one where I feel I am being carried and inwardly directed. I respond without doubting or questioning. I act immediately in the moment. It’s not difficult and does not involve rational thought or consideration. I don’t weigh things up; the experience is spontaneous. There is some sort of inner knowing. It feels very easy, as if it were the easiest thing in the world really. I feel alive – an inner energy and force moves me.

Deborah is an experienced senior IT leader and manager in a multinational organisation:

It’s quite difficult to explain this experience of being in flow. It’s a tangible feeling that things are happening in a positive way, with actions interlinking and events unfolding as time moves on. It doesn’t feel like there is a predetermined pattern, but more like riding the crest of the wave and being simply able to take opportunities that come along as I am travelling forward. It feels like some sort of magical force is at play, which I have found a way to tap into, and it is giving me the ability to do more and see more than before.

Note how mastery involves little or no effort and it is an inspired activity. The masterful coach within is the source of our motivation to act and guide.

• The emerging faculties •

Discovering mastery seems to be characterised by the emergence of particular faculties – intention, intuition, imagination and integrity. These faculties begin to emerge into more conscious use with the opening of the creative eye and being at one with the inner compass. I often imagine each of these faculties aligning with the directions of the compass, as illustrated in Figure 19, opposite.

Figure 19

These faculties inform how we act and the direction we consciously take. They collectively combine to offer masterful practice and create a fifth faculty – presence.

Intention

The faculty of intention is a conscious setting of a clear direction in the mind of the coach. Setting intention provides the opportunity to plan our life and work in advance by consciously identifying, before we begin, what we would ideally like to happen.

Intention helps the coach to navigate and to plot the way in advance

It provides the coach with clarity of purpose and direction. If intention is not consciously set, then we often fill the space with activity. We fire-fight and feel there is never enough time to complete our work. Intention is like a lamp we consciously light that can illuminate, remind and clarify each step of our journey.

When I begin to coach a client and set the coaching frame, I commonly make my intention clear to the client: ‘I am committed to your development and helping you to fully realise your most desired change. You are my primary focus. You will have my full attention and support. I intend to get to know you well.’ Being clear and stating my intention affirms not only my commitment and the intended direction of the work, but also what the client can expect of me.

An important part of the role of the coach is to help to clarify the intention of the client. This leads to questions such as: ‘Remind me, where, ideally, would you like to get to with this?’ ‘If you could wave a magic wand, what would change for you?’ ‘What does realising your goal look and feel like?’

Pause point

How do you employ intention in your coaching practice? What is its specific value to your work?

In modelling the value of intention, the coach can help the client to realise its value. Let me share an example from a recent coaching session with Simon to illustrate this.

When we first met, Simon told me how he would often go into key business meetings quite unclear of what he needed or wanted. This created the sense of feeling lost and needing other people to set direction for him.

Simon: | I think I’m quite needy, I need a lot of guidance. |

I see how Simon turns to others for the answer and devalues his own ability to answer and set his own course.

Coach: | Who do you trust to guide you? |

Simon: | (Pause) I always feel a little lost and need other people to give me direction. |

Coach: | There’s probably only one person who knows what you truly want and where you would ideally like to get to, is that not true? |

Simon: | Who’s that? (We smile, long pause.) Me? |

Only you. Without a compass and a sense of direction your boat is simply lost at sea. | |

Simon: | Mmm (pause). I never ask myself for direction |

Coach: | Yes I know. How do you feel in your search? |

Simon: | Lost. |

Coach: | How might you set sail differently? |

Simon: | (Pause) By deciding up front what I need, maybe. |

Coach: | Excellent! How might you do that? |

We explored how, rather than asking others continually for direction, Simon could set his own by being much more conscious of what he wanted, and naming this intention from the start in meetings and to the people with whom he interacted.

One month later, in our next coaching session:

Simon: | I had a revelation last time – and it has changed me. |

Coach: | Tell me more? |

Simon: | Intention – setting my intention has changed me. |

Coach: | How? |

Simon: | I feel more in control, my confidence is building and I am trusting in my own judgement much more than before. |

Coach: | What is the difference you experience? |

Simon: | I’m not as needy and people are surprised when I state my intention. I hadn’t realised how I was constantly trying to work out what others wanted and meeting their expectations, forgetting about myself. I have a greater self-worth now. I listen to me more. |

When we met the first time, on a scale of 1 to 10, how were you feeling in terms of self-worth and confidence? | |

Simon: | A 3 or 4. |

Coach: | What about now, after what you have learned around your intention and how you are using this? |

Simon: | It’s a 7. |

Coach: | Taking charge and consciously setting your course has served you well – your confidence and self-worth have shifted. What might make it an 8 or 9? |

Simon: | Practice (we smile). |

Observe the difference that one coaching session can sometimes make to the client’s self-esteem and worth. Part of the work of the coach is to remind the client and help them to utilise their inner resourcefulness, including the power of intention. This is an important faculty of mastery.

Intuition

The second faculty that we more consciously discover together with the masterful coach is intuition. This is when, through our expanded awareness, we suddenly catch a glimpse of the larger field in which we are a part. It seems to be a direct vision and experience of reality simply as it is. Maybe we see wholeness before it is reasoned and rationalised.

The masterful coach is often highly intuitive and conscious of the importance of these sudden glimpses, aware of how they can inform the receptive mind and heart, and offer new important possibilities. Being sensitive and willing to respond to intuition is an essential aspect of the masterful coach. It can give clues and often a deeper insight into what is important to the client.

Pause point

How do you employ intuition in your coaching practice? What is its specific value to your work?

I recently worked with a human resources director, Veronica. In our first session, I intuitively saw her quite transfigured through my mind’s eye. This may seem very strange, but intuition can be. The question is if and how we can work with it. The following extract is taken from our first session.

Veronica: | I have a large business responsibility and too much work. |

From out of nowhere I suddenly saw my client in my mind’s eye wearing a white wedding dress and veil. I immediately connected this with a princess from a fairytale in a Walt Disney production. This happened two or three times while my client was speaking, although Veronica was wearing a formal business suit. I inwardly smiled, recognising my intuition and its strangeness, and, by trusting it, I decided to explore.

Coach: | What are your favourite pastimes? |

Veronica: | I don’t have a pastime with the children. |

Coach: | Mmm (pause). What about your favourite DVD? |

A favourite DVD, film or book can often give insight to the deep aspirations of your client and what they particularly value and care about.

I’m a bit shy to share that. | |

Coach: | Why Veronica? |

Veronica: | It’s a children’s DVD. |

Coach: | I’m curious now. |

Veronica: | It’s called The Princess Bride. |

I was quite astonished that this fitted so well with the wedding dress I’d visualised before with my intuitive eye.

Coach: | Why is the DVD so important to you? |

Veronica: | It’s full of hope and has a happy ending. |

Although I remain deeply curious of the importance of the DVD and the central character to Veronica, we never fully completed the work. Veronica found herself facing a major work change and quite a traumatic period and decided, for whatever reason, to step out of the coaching relationship. Veronica may return to continue with the coaching at some point, but until then I am left very curious about the deeper significance and importance of The Princess Bride.

The masterful coach is able to completely trust and value the client’s intuition as well as their own. The reaction of the analytical eye is to dismiss these irrational thoughts. One of the gifts of the masterful coach is to be able to include what may seem totally irrational as a way to provide an important new context for learning and development. This is demonstrated in the following case study.

I was working with a senior finance director, Sam, a prominent and responsible figure in his organisation. We were exploring the model of the three eyes. We had examined the analytical and appreciative eyes, and were now moving to explore the creative eye.

Sam has a strong rational side, and the vision of the analytical eye can at times dominate his outlook and approach to work and life. Increasingly, he has found that when he created space at weekends he was unable to relax properly. The demanding ‘shoulds and musts’ of the analytical eye were invading his need for down-time. In the following coaching conversation we arrive at an exploration of the creative eye.

Coach: | One way I think of the creative eye is with this (I place a coin out of my pocket on the table in front of Sam and smile). |

Sam: | How does this relate to the creative eye? |

Coach: | The creative eye opens when you consider the analytical and appreciative eyes to be like two sides of the same coin. Their limitations balance out and a new way of seeing is now possible. |

Sam: | It reminds me of university. |

Coach: | Tell me more. |

Sam: | I loved ‘systems thinking’ at university. My tutor used to call finance a safe study. I was very interested in systems thinking and wanted to explore that much more. |

Has my client had an intuition – as systems thinking has just entered his mind seemingly from nowhere? I start to muse about what might be happening and the importance and relevance of this intuition to Sam. Why now?

Coach: | What did your reading on systems thinking give you? |

Sam: | It was different, exciting. I wanted to study it. |

Coach: | I wonder if your chance to read more on this topic is being presented once more? |

How come? | |

Coach: | The creative eye differs from both the analytical and appreciative eyes in that its vision can accommodate a third dimension – the universal.We can expand our vision to appreciate the larger system in which we live and work through the creative eye. |

Sam: | Is that so? |

Coach: | Trust your intuition, it’s not by chance that you have connected with systems thinking – you may be being invited to do so once more. |

Sam: | How interesting. |

Imagination

The writer Thomas Moore kindly composed the preface to my last book and, while doing so, emphasised the central importance of the imagination by reminding us of oculus imaginationis – the all-seeing eye of the imagination. This eye literally gives form to our sense and shapes our thoughts and experiences into new possibility. Through the imagination we encounter the world. Our minds travel to explore imaginatively what might or will be.

Through the imagination we can re-energise, open up and experience something more of the present, past or future. Your past can be re-imagined in the present. Through the active imagination of the creative eye we can feel our way into different situations and places.

The imagination enters the virtual, wanting to make it real

Imagination is the great sculpture and artist and is enlivened and increasingly active through the discovery of the masterful coach. When clients feel stuck they can conjure up an image or metaphor of where they might like to be. That representation of their experience of being stuck can also be a bridge to change. The imagination is our natural bridge between form and experience and is a vital part of coaching practice. Let me share with you an example from recent coaching work.

Pause point

How do you use imagination in your coaching practice? What is its specific value to your work?

Ruby is a senior leader within a major international organisation. She has recently been frustrated and angry, and has behaved badly in senior board meetings. She wishes to explore what’s going on in more detail.

Ruby: | I get angry, frustrated and then start to become quite disruptive. |

Coach: | What does that look like? |

Ruby: | I behave badly in the room. |

Coach: | Have you discovered a saboteur, I wonder? |

Ruby: | Yes, but I didn’t realise just how disruptive I may have been. |

Coach: | Would you like to get to know this character a little more? |

Ruby: | Yes. |

Coach: | Imagine him or her to be a character of some sort, standing here with us now. What sort of character would he or she be – what size, shape, features, colour? |

I invite Ruby to employ her active imagination in order to meet with this character more fully.

Ruby: | He’s dark, very dark. Large, very sharp, incisive and masculine. |

Coach: | Anything more? |

Ruby: | I think he wears a mask. |

Coach: | Do you have a name for him? |

Ruby: | (Laughs) Let’s call him (pause) Darth Vader. |

Coach: | I can certainly see his power to disrupt now (we laugh). How does he limit your work? |

Ruby: | (Pause) He causes problems, he tries to disrupt and spoil things. |

Coach: | So he seems to limit you by being highly disruptive in important meetings. How does he serve you? |

Ruby: | (Pause) I don’t know. |

Coach: | Stay with it Ruby. |

Ruby: | (Pause) He stands up for the part of me that doesn’t get seen. |

Coach: | Say more? |

Ruby: | (Pause) I’ve just realised that he comes out when I feel overlooked and not included. I have a lot to say, but I somehow can’t get in to say it, or don’t feel invited in. I get so angry because of this, and so I send in Darth. |

Coach: | So Darth comes out when you feel excluded and can’t add your significant experience to the discussions? |

Ruby: | Yes. |

So you want to contribute and show your value and if that doesn’t happen you send in Darth to create a little havoc? | |

Ruby: | Mmm (pause). That’s true – exactly so. |

Coach: | I know Darth is serving you, but how is he affecting your reputation, Ruby? |

Ruby: | Wow, well (pause), he’s not doing me any favours. I get so angry. |

Coach: | If your anger had a voice, what would it say? |

Ruby: | (Long pause) I am invisible and I have so much to say. It probably says, help me out! So I can share my experience. |

Coach: | I imagine that’s very frustrating for you. |

Here I am empathising – I can see how hard this experience is for Ruby and how it is troubling her.

Ruby: | It is. |

Coach: | What are you learning from this – in giving Darth shape and form? |

Ruby: | He’s a bit of an overkill and it’s doing my reputation no good. |

Coach: | Could you contract with Darth? |

Ruby: | How? |

Coach: | Can he help you to come in, in some way, rather than trashing the place (smile)? |

Ruby: | Maybe (pause). When Darth comes out and I’m angry, he can maybe remind me that I need to speak out and bring my experience in. Maybe he can stand and guard me while I try? |

Coach: | Would his presence help you in this way? |

Ruby: | Yes, I might not feel so alone. |

So you can contract with him to be a protector and an aid rather than be totally disruptive (smile)? | |

Ruby: | Yes, I can. |

Coach: | May the force be with you (we laugh). |

Note how my client is able to give form, shape and character through her imagination to an aspect of her personality, Darth. Ruby then explores how she might more consciously direct the behaviour of Darth to help her.

As work with Ruby continued, she surprised her senior colleagues by not being disruptive, but asking their help to make sure that she could bring her experience and knowledge into the group. This allowed her to make a significant and important contribution at board level and feel much more satisfied in her work. I still hold a treasured picture of Ruby and Darth sitting together at the board meeting.

Integrity

As you develop your coaching practice, your integrity will deepen. In this way I consider it to be an emerging faculty that we consciously discover together with the masterful coach.

Integrity is the satisfaction that comes from feeling more whole, complete and accepting of our truest nature

Let us briefly revisit and summarise how integrity is deepened through the coaching relationship. We judge and divide the self, rejecting what we label as bad. These banished aspects are pushed away, ultimately beyond our conscious awareness. We create a safe but divided and partial self that longs to be more whole and complete. The client turns to the coach to understand more fully and illuminate their hidden desires and the wish to change and develop. Through this trusting relationship – by examining behaviours, needs and aspirations – these denied and hidden aspects can once more be made conscious and be accepted back.

What was hidden or unconscious can be discerned by the shared vision of the coaching relationship and given back to the care of the client.

At the heart of coaching is a process of discovery, acceptance and reintegration

Through acceptance and deepening self-awareness, the client aspires to become more honest to their true nature and to experience wholeness – their original self. This aspiration deepens the authenticity and integrity in ourselves and how we relate. Returning for a moment to the jigsaw analogy, coaching helps the client not only to identify the pieces, but also, if each piece is accepted, how they fit together to become an integrated whole.

• Presence and presencing •

The faculties of intuition, imagination, intention and integrity offer a remarkable sensitivity to orientate, discern, relate and resolve. Collectively they inform the ‘presence’ of the coach. What we mean by the experience of presence is not easy to describe.

Presence has a number of different dimensions. It describes the qualities of mastery in the coaching relationship – for example, your experience of a highly responsive, calm and deeply attentive coach. Presence, or ‘presencing’, may also describe an activity – the coach can help the client to feel the presence of the larger energetic field in which they participate. The coach who has discovered mastery can help to conceive and inform the larger context – the universal field – in which the client participates. The ideal future and the person we most aspire to be are both awaiting our attention and conscious expression. Might these already exist in potential and prospect?

Another way of thinking about the inner process of presencing is that we are drawn through our longing to make conscious the presence of our original being. Presence and being are intimately related.

Presence maybe reflects our capacity to express the original self from which the qualities of mastery originate

To conclude this chapter, let us now explore some of the qualities of mastery that inform presence.

• The qualities of mastery •

Many years ago, as a biochemist, I researched the impact of pesticides on aquatic life. It often involved going out on the Scottish lochs to sample the fish life. My colleagues, guiding the small boat, would remind me that when the weather is bad (as was commonly the case!) the fish go deeper and are much harder to catch. This made fishing much more challenging. Similar to the fish, when our own surface waters are choppy and chaotic, or when we are distracted, our qualities seem to go deeper within and remain hidden. It is only when we discover a period of calm that our deeper qualities, like the fish, can re-emerge, surface and find expression.

The more we learn how to still ourselves through the discovery of the inner compass, the more we can experience the presence and power of our inner qualities in practice. Such qualities may include compassion, peace and wisdom.

With the opening of the appreciative eye, we discover empathy and our capacity to relate. With the emergence of the inner compass, our capacity to be still and attentive deepens. This stillness permits the qualities of compassion, peacefulness and wisdom to emerge into our practice. One very pertinent and enigmatic question to ask is: ‘Is the difference we make through coaching more a consequence of how we are than what we do?’ I recall one rather complex incident in my coaching practice where compassion played a vital role.

Edward is a very senior and visible leader, working at the highest levels of the organisation. We have a strong coaching relationship. One day I received a very distressed phone call from him. In a moment of being placed on the spot facing a large audience, he had spontaneously said something that was deemed by some of the audience to be inappropriate and offensive. Edward was distressed by his mistake and I agreed to meet with him immediately. Never have I seen someone so upset as a result of a mistake. He told me that he stood on the brink of resignation because of his error and the pressure from some key people.

We worked through what had happened and how he had apologised openly and specifically to those concerned and most impacted. I reassured Edward that I would support him through this period and we explored the next steps. I took my own experience of this session to supervision. I was deeply moved by the impact of this error on Edward and, with the guidance of my own experienced supervisor, I found myself asking ‘Where in the organisation is the voice of compassion rather than judgement?’

This was a delicate and complex situation and not an easy one for any coach. I knew Edward’s sponsor well through our coaching triangle – sponsor, client and coach. I contacted Edward and checked if he was OK with my speaking to his sponsor. He was. In that meeting I reflected with Edward’s sponsor the dilemma that Edward faced. Edward had completely accepted his error and misjudgement and had apologised openly. Should this end the very successful career of someone who had made a major contribution to the success of the business and organisation and was quite exemplary to this point? I turned to his sponsor and asked: ‘Where is the voice of compassion within this organisation?’

The sponsor was pensive and receptive and subsequently intervened at the highest levels to ask the same question of some of the key individuals involved. The result was that Edward did not resign and was allowed to stay and to work with his error. He owned his fallibility and grew through this experience. His successful career continues.

The boundaries of the coaching frame between the client and sponsor are not always clear. Ultimately, we may need to remind ourselves of our priorities and why we coach. Compassion is a key quality I strive to express in my work. It is a quality that reminds us of the importance of the conscience of the coach. With compassion, as in this case, we can discover and are humbled by our fallibility, and in accepting fallibility we give ourselves permission to be real and authentic. In becoming real and authentic, we discover the joy and freedom of mastery.