The Role, Structure and Positioning of the AML/CFT Compliance Function

Best practice in higher-risk products and services

Management of internal suspicion reporting

Where you see the WWW icon in this chapter, this indicates a preview link to the author’s website and to a training film which is relevant to the AML CFT issue being discussed.

Go to www.antimoneylaunderingvideos.com

STRUCTURE AND CULTURE

Core activities for the AML/CFT role

These can be summarised as follows:

- securing senior management support

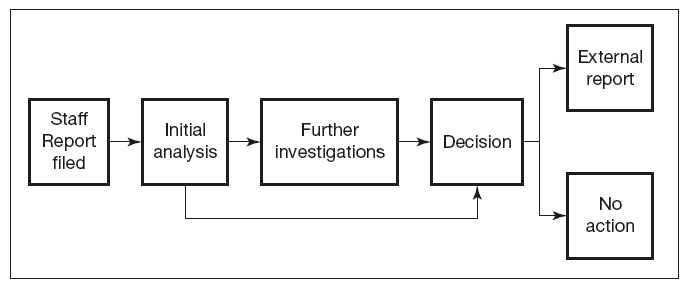

- receiving and analysing internal disclosures of suspicious activity from staff

- making external disclosures of suspicious activity to the authorities

- producing, monitoring and updating policies and procedures

- using international findings and UN and other watchlists

- staff training and awareness

- reporting on AML and CFTto senior management

- responding to information requests from competent authorities

- general oversight of the bank’s overall AML/CFT effort.

Key policies and procedures

These should include the following as a minimum:

- name screening (client acceptance)

- risk assessment (client acceptance)

- identification (client acceptance)

- due diligence and enhanced due diligence

- account monitoring

- sanctions and prohibited transactions

- suspicion recognition and reporting

- records maintenance

- training, awareness and communication

- incorporation of international findings

- staff screening.

Position of the AML/CFT role within the organisation’s structure

The exact place of the AML/CFT compliance role within the overall structure of the organisation is not prescribed internationally, and so will depend upon any national requirements and on the preferences of the organisation and its senior management.

In the largest international banks, the position of Head of AML and CFT is a senior position which is well remunerated and offers enough direct access to senior management to be able to function effectively. Typically the AML/CFT function will fit within one of two models:

- As part of a wider financial crime function. In this model, AML and CFT sit within a specialist unit which also deals with fraud prevention and other types of financial crime such as insider trading, market manipulation, tax evasion and, more recently, proliferation financing.

- As part of a wider legal and compliance function. In this model the AML/CFT function sits within a wider unit which, apart from AML and CFT, also deals with issues such as:

- compliance with other banking rules and laws

- compliance with the organisation’s code of conduct dealing with issues such as conflicts of interest and other ethical matters relating to integrity and anti-corruption.

It is of course also possible for the unit to sit completely independently, as a statement of the importance attached to it. If that is the case, then the reporting line of the head of the unit should be at least to Executive Director level and preferably to the Chief Executive Officer, in order to avoid the risk of the unit being bypassed in important decision-making processes.

AML/CFT units are rarely part of the audit function. This is because they must themselves be subject to scrutiny and oversight in relation to the effectiveness of the way in which they perform their duties. This would not be possible if they were part of the audit function, whose job it is to provide management with assurance that different functions in the organisation are doing their jobs efficiently, including the AML/CFT function.

The so called ‘three-line defence model’ for AML and CFT sees the organisation setting up three tiers of protection against the various risks posed. These are:

- First line of defence – at line management level. Relationship managers, branch managers and supervisors and their front line staff comprise the outer armour of the organisation’s defences. They are relied upon to be aware of the risks and to apply policies and procedures as they have been laid down, for example in relation to issues such as identification, account monitoring, name screening and suspicion reporting.

- Second line of defence – AML/CFT unit. The AML/CFT unit itself forms the second line of defence. The unit exercises general oversight of all AML and CFT activities within the organisation including:

- designing policies

- conducting training

- engendering senior management support

- monitoring and reviewing the application of policies within the business units.

- Third line of defence – audit department. The organisation’s audit department provides the third line of defence, conducting full audits not only of business units (which should also include AML and CFT checks and sampling) but also of the AML/CFT function itself, to provide assurance to the Board and Audit and Risk Committees that it is doing its job properly.

Organisation of the AML/CFT role

In terms of who does what within the AMT/CFT function, in a small organisation one or two people may handle everything from business queries to training, to writing policy, to arranging IT support for name screening, etc. As an organisation gets larger and more complex, however, this clearly becomes inappropriate and a division of responsibilities becomes necessary.

The precise nature of the division, if not prescribed by local law, is a matter for the Head of the AML/CFT function to decide. For example, a Head in a reasonably large organisation might split the responsibilities of the function as follows or, where resources are tight, allocate clusters of them to individuals:

- regulatory and FIU liason and reporting

- receipt and analysis of internal Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs)

- sanctions, blacklists, name screening and client acceptance

- policy, training and international compliance

- day-to-day operational advice to business units.

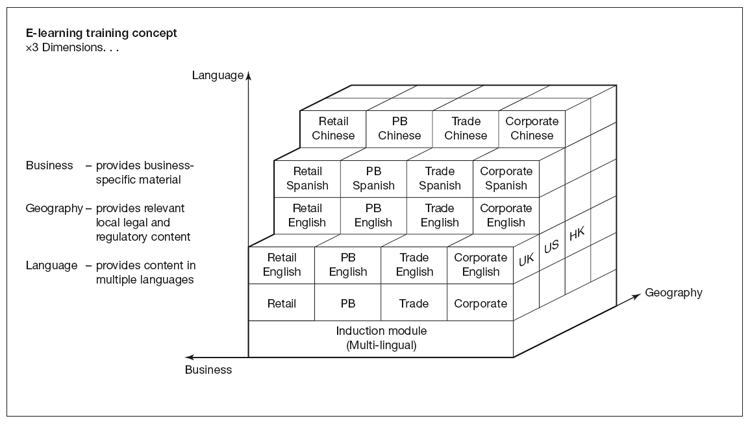

The very largest organisations will need to operate matrix structures in which different roles are performed across multiple products in different business streams across multiple jurisdictions (if the organisation is expanding internationally). These structures may, for example, see different heads of AML/CFT distributed through the organisation on a business or geographic basis, with double reporting lines to both the general managers of those businesses and into a main, centralised AML/CFT function sited in head office.

In such cases, the more complex the structure needs to become, the more important it is that there is great clarity as to who is responsible for what – in particular the statutory responsibilities laid down under national law and, of course, clarity within the organisation as to whom suspicious transactions should be reported.

Importance of a strong compliance culture

Whereas all core activities in the AML/CFT role are important there is one activity in particular which is paramount, and that is securing senior management support. Compliance starts from the top and without the commitment of senior management the role of the AML/CFT Compliance Officer becomes that much more difficult, and some might even say impossible.

Why is this? The answer is that the senior managers in organisations occupy positions of such power that effectively they determine the culture of the organisations which they lead. Whether it is because subordinates want to impress them, or because they are fearful for their jobs, or because they act purely from habit may differ from case to case. But the general indication is that people’s propensity to follow orders at work and ‘go with the flow’ is extremely high.

What is the evidence for this? Much research has been done in this area but two psychological studies conducted in America in the 1960s are particularly worthy of mention. The first, undertaken by Stanley Milgram, placed subjects in a situation where they thought they were taking part in experiments to determine a person’s capability to follow simple instructions, with a small electric shock being administered if the person followed the instruction incorrectly. They were assigned the task of the ‘teacher’ and had to administer these small electric shocks to the ‘student’ who was situated on the other side of a pane of glass, the two being separated by a contraption described as an ‘electric shock machine’. The arrangement is shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Milgram’s famous experiment

In fact there were no electric shocks and the real subjects of the experiment were the ‘teachers’ who were being asked to administer what they believed to be increasingly severe electric shocks to the ‘students’ (who were in fact actors) for no other reason than that they had got the answer to a simple question wrong. As the ‘shocks’ increased the ‘students’ displayed increasing amounts of distress. Milgram’s ‘teachers’ were accompanied by authority figures in white coats (the experiments were conducted at Yale University in the US) to whom they frequently appealed during the experiments for permission to stop. Always, however, the answer came back calmly but firmly to proceed with the administration of the ‘electric shocks’. Milgrim was interested to test how far people would go in following instructions from an authority figure. The results were extraordinary. Very high percentages of the subjects (sometimes up into the 70 per cent bracket) would proceed to administer what they believed to be lethal electric shocks to the ‘students’. This led Milgram to his chilling conclusion: ‘A substantial proportion of people do what they are told to do, irrespective of the content of the act and without limitations of conscience, so long as they perceive that the command comes from a legitimate authority’. (Source: www.stanleymilgram.com/quotes.php)

If Milgram’s experiment dealt with people’s propensity to follow orders, then the experiments conducted by another American psychologist named Solomon Asch graduated more towards people’s willingness (or otherwise) to speak out in a group when they believe that something is wrong. Asch sat his single subjects in groups with 11 others, all of whom knew the true purpose of the experiment, with only the subject unknowing. A group would be shown different images of lines of differing lengths and were asked to state which line was longer, which was shorter, etc. Each member of the group would state his or her opinion in turn. The subject was always in the latter half of those asked, such that the majority in the group had already given their opinion by the time it came to the subject. The differences in the line lengths were quite obvious. For a couple of rounds in each group, the majority of those asked ‘Which was the longer line?’ gave the correct answer, as did the subject. However, at a certain point the majority gave wrong answers and, again, in surprisingly high numbers the subjects would agree with the majority even though the evidence of their own eyes was telling them quite clearly that the opposite was true.

These two experiments demonstrate what most of us have probably already experienced: that in organisations people tend to do as they are told and are, by and large, very reluctant to speak out when they receive an instruction which they believe to be ‘wrong’. Applying this to an AML/CFT culture it becomes easy to see how such a culture would be weak and ineffective unless senior management is not only ‘talking the talk’ but also ‘walking the talk’, i.e. insisting upon adherence to necessary standards, even where that may mean giving up a short-term revenue gain.

Example: The case of the rising star

In one financial institution there was a policy which stated very clearly that: ‘In case of doubt we do not hesitate to reject potential customers or terminate business for AML concerns, even if it means losing profitable business. Consequently we accept from staff a critical attitude with regards to new customers.’ A young relationship manager, aware of the policy, was publicly criticised by his manager in team meetings when he raised concerns about certain new customers and the origin of their wealth. He was told, ‘Go and join the Compliance Department, you’d fit in better there than you do here,’ and he was overlooked for promotion and received a lesser bonus than some of his colleagues. He raised the matter privately with the Compliance Department who, after getting nowhere with the business manager concerned, escalated the matter to the CEO, explaining that in its view it was essential that the business manager should get a clear message from the CEO that the AML policy was meant to be followed in practice. The business unit run by the manager was, however, performing extremely well. Its revenues were at record levels and undoubtedly the manager was partly responsible for this.

In spite of several subsequent requests, the CEO took no action, choosing rather to issue a generally worded memo to all staff about the importance of the AML policy. A month or two later, another manager in the business unit informed Compliance that the manager had treated the matter humorously in a subsequent team meeting, quipping that the CEO needed him more than he needed the Compliance Department. The second manager said, ‘Everyone knew what had happened and everyone knew what the outcome had been. From that moment on nobody was in any doubt that, whatever the AML policy said, the view of their manager, backed by senior management at the highest level, was that whenever the policy jeopardised profits, it could be overlooked.’

Gaining senior management support

Genuine support from senior management is so essential that nothing good or effective will be achieved without it. There are some obvious things that you can do on a personal level to foster support from senior managers, such as:

- communcating with senior managers regularly, both orally and in writing

- regularly sharing information with senior managers about different aspects of AML/CFT compliance (but don’t become a bore)

- inviting senior managers to contribute to discussions about AML/CFT compliance (e.g. at department meetings or training sessions)

- ensuring that news of positive developments reaches key senior people, whilst also ensuring that any ‘bad surprises’ are flagged up as early as possible, together with options and recommendations for resolution

- developing good relationships with regulators whose views senior management must take note of.

However, AML/CFT compliance officers must appreciate that it is insufficient simply to write lots of memos and other communications pointing out what the laws and regulations say. To achieve real commitment and all the good things that flow from it the AML/CFT function must adopt an approach that is business-focused, one that casts AML/CFT compliance as something that is there to help the business succeed, rather than as a ‘blockage’ to be got around or ignored.

The foundation stone for your business-focused approach should be a desire to achieve (or, if a great one exists already, to maintain) the right culture within the organisation. This will not be a culture in which the business views compliance as being the Compliance Department’s problem, but rather a culture in which the business takes ownership of compliance for itself and incorporates it seamlessly into its business processes, with the support and help of the CEO and senior management team and the Compliance Department. This type of culture is typically achieved by:

- a business-owned governance structure that puts a heavy emphasis on business responsibility for compliance

- a complete set of policies that can be ‘seamlessly’ integrated into each business unit’s operating procedures and that apply in practice as well as on paper

- adherence to current best practice, demonstrating a commitment to anticipate and keep pace with a rapidly developing regulatory environment

- IT systems designed to assist the organisation in fulfilling its obligations and in meeting its AML/CFT objectives

- a continuous training and communication programme emphasising the importance of AML/CFT compliance and equipping staff so they can comply with both organisational policy and national law.

- A proactive, business-friendly approach from AML/CFT Compliance Officers, with an emphasis on efficient and effective suspicion reporting management.

Business ownership

What practical steps can you, the Compliance Officer, take to embed responsibility for AML/ CFT compliance within the business itself? In terms of corporate governance there are a variety of possible measures, outlined below.

Policies

Corporate policies should state clearly that responsibility for compliance lies with business units. For example:

‘Business heads are responsible for ensuring that procedures and controls commensurate with these standards and guidelines are in place for all units under their control.’

Anti-Money Laundering Group (AMG)

It is not sufficient that business managers’ responsibility for compliance should simply be incorporated within policy documentation. Managers will need reminding on a constant basis that responsibility is theirs. A good mechanism for achieving this is a regular AMG meeting, comprising the heads of the major business units concerned, briefed to discuss AML and CFT issues specifically. The AMG should be chaired by the chief executive or general manager and would consist of the heads of businesses, the Chief Operating Officer, the Compliance Officer and any other key personnel. An example agenda is shown below:

Example: AMG AGENDA

for the meeting to be held on [date] at [place]

- Minutes and action points from last meeting on [date].

- Update on Suspicious Activity Reporting (Compliance Officer) and ‘live issues’ from business units.

- Progress on staff training and awareness and other initiatives within the anti-money laundering strategy (each Business Head).

- Policies and procedures – any points arising.

- Legal and regulatory update – including global/international developments (Compliance Officer/MRO).

- A.O.B.

- Next meeting.

Chaired by the Chief Executive Officer, or in his absence the Deputy CEO or Chief Operating Officer (COO).

For attendance – Heads of Businesses, COO and any other key personnel agreed.

Link to performance

Responsibility for AML/CFT compliance should also be built into the organisation’s performance management framework, thus ensuring that observance of AML/CFT good practice is one of the measures against which managers’ work performance is assessed. Specific AML/CFT objectives can be included within a business manager’s overall personal performance objectives. Similar provisions can be cascaded down into the objectives of more junior staff. This will highlight the importance of AML/CFT compliance and signals clearly that bonuses may be at risk if compliance performance objectives are ignored. An example for a senior business manager might be as follows:

Example: Anti-Money Laundering objectives

During the assessment period, actively to assist the bank’s drive against money laundering and to provide business leadership on money laundering prevention by:

- attending and contributing at the senior management AML meetings

- implementing action points agreed upon and decisions made at AML meetings

- attending and, where appropriate, introducing staff training sessions on AML

- achieving a score of 18 or more in the 20 questions AML ?self-assessment test administered by compliance.

Compliance Champions

It is rare that an AML/CFT function will have sufficient resources and personnel to have an employee present in each business unit. Even if it did, as representatives of the Compliance function such employees may be viewed as separate from the business. A ‘Compliance Champion’ therefore is an employee who sits within the business and undertakes certain specific activities such as:

- distributing information (e.g. articles or briefing notes) about a particular topic received from the AML/CFT Compliance Officer

- helping in the organisation and delivery of formal training sessions and training programmes on AML- and CFT- related topics, in conjunction with the Compliance Department

- providing the AML/CFT Compliance Officer with direct feedback on the effect of certain policies and procedures on the business, and making suggestions for improvement

- periodically meeting up with the AML/CFT Compliance Officer and Compliance Champions from other business areas to discuss compliance issues and problems and recommend practical solutions which will work at the point of business

- delivering short, informal briefings on compliance-related topics at, for example, business team or management meetings.

Because of their proximity to the business, Compliance Champions are unable to undertake any kind of independent assessment of compliance standards. This must be done either by the Compliance Officer or the Audit Department in accordance with the three-line defence model discussed earlier.

Communication of requirements

Setting up a business ownership structure as outlined above requires communication – from the Compliance Officer to the Chief Executive, and from the Chief Executive to business heads. Shown below are examples of the documents that might have a role to play in such a strategy, based around the three themes of:

- creating a ‘culture of compliance’

- embedding responsibility for compliance within business units

- the development and maintenance of sound AML and CFT policies and procedures.

Clearly the Compliance Officer should discuss their overall approach with the CEO beforehand and obtain their support for the approach, but otherwise these memos are practical documents which, when taken in conjunction with a senior management presentation and a staff briefing, for example, could form the basis of an effective communication strategy to explain the business ownership approach advocated here.

Example

MEMO TO CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER RECOMMENDING ACTION STEPS ON MONEY LAUNDERING RISK

Re: Money laundering risk – Action going forward

1. I refer to our discussions regarding the above, and now set out formally, as requested, my observations on how [Name] Bank should best deal with the management of money laundering and terrorist financing risk going forward.

2. In common with other regulated banks and financial institutions in [Country], we have been complying with [Central Bank] regulations regarding the opening of customer accounts, the mandatory reporting of certain transactions and the reporting of unusual or suspicious transactions for some time. However, in view of international trends in relation to money laundering prevention, which clearly indicate:

- a significant tightening of regulatory standards

- a significant increase in the reputational damage likely to be suffered by defaulting banks, and

- a significant increase in likely penalties to be imposed upon defaulting banks – including possible denial of access to the financial system in key areas such as the US, EU etc.

I believe we (the senior management team) now need to adopt a strategic approach to this issue, and to formalise the general increase in awareness which we have all felt, into a concrete and comprehensive plan of action which is visible to staff, customers and regulators alike. The medium- and long-term aims and benefits of doing this will be substantial and will include: - a reduced risk of use of our bank by criminal elements

- in the event that such use does occur against our best efforts, a much greater ability to defend ourselves from criticism, due to our having initiated voluntarily a programme of best practice measures which complement the minimum regulatory requirements

- as a result, a strengthening of our overall risk management capability.

3. I believe that our strategy should concentrate on three broad and complementary areas or ‘themes’ of action, and I outline what these are below, together with some of the practical measures which we can implement to bring them to life.

THEME 1: BUILDING ‘A CULTURE OF AWARENESS’ AMONGST STAFF IN RELATION TO MONEY LAUNDERING

In best practice benchmark organisations, all staff – but particularly those in key areas – are aware of the risks posed by money laundering and terrorist financing, and of the steps which are expected of them in trying to prevent and/or to identify it. This means much more than just making the relevant laws and policies (see below) available to staff. It means imbuing them with an instinctive vigilance which they, whilst remaining hungry for business, then apply to all customers and all transactions. Actions to achieve this objective would include:

- regular training (suited to job, grade, etc.)

- regular distribution of relevant materials and resources

- periodic surveys to measure awareness

- periodic assessments to test knowledge

- suitable treatment of the issue during the staff induction process

- ‘stress testing’ of vigilance in, for example, branches

- overt and unequivocal senior management support for the anti-money laundering message.

THEME 2: EMBEDDING RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING COMPLIANCE WITHIN BUSINESSES

In organisations where the primary responsibility for ensuring anti-money laundering compliance is seen to rest with the Compliance/Risk function, businesses never fully accept their role in preventing money laundering. Management time is wasted as businesses and risk functions adopt ‘us and them’ postures. Risk is increased as, freed from responsibility for the ultimate outcome, businesses attempt to accept business which they may be less than sure about. Genuine revenue opportunities are lost as compliance/Risk functions, feeling pressured and under attack, veto business which might otherwise be accepted.

In best practice benchmark organisations, however, primary responsibility for compliance lies with the businesses, where such compliance is seen as an integral part of the business cycle. Actions to achieve this objective would include:

- specific CEO memorandum to business heads, setting out their responsibilities [see ‘BusinessACMem.doc’]

- policies and procedures which specifically include statements of business responsibility and accountability [see ‘Policy’.docs (various)]

- ensuring that policies and procedures are observed day-to-day, by rewarding compliance and punishing non-compliance

- the launch of a senior management group, called the Anti-Money Laundering Group (AMG) to oversee [Name] Bank’s overall anti-money laundering effort [see ‘BusinessACMem.doc]; such group to include heads of businesses

- inclusion of a specific anti-money laundering objective in the personal job objectives of business heads and all other staff, with performance against this objective being included in a person’s annual appraisal

- during anti-money laundering training, a continuous emphasis on the personal responsibility of staff for the prevention and identification of money laundering

- the appointment of specific people at a more junior level within businesses to act as ‘Compliance Champions’ (this role to be ‘double hatted’ with their existing roles), assisting the Compliance Officer/Risk Manager with various tasks such as training and the dissemination of relevant materials and resources.

THEME 3: THE [DEVELOPMENT OF] [MAINTENANCE AND ENHANCEMENT OF OUR] ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING POLICIES AND PROCEDURES

We must [develop] [maintain and enhance our] policies and procedures in key areas connected with the fight against money laundering, so as to ensure that [Name] Bank’s position on anti-money laundering is clearly spelled out, and that staff have clear standards to follow. These must be adapted to be specifically relevant to each type of business and should [be updated to] cover the following issues:

- screening against international, regional and national ‘blacklists’

- customer identification and risk assessment

- ‘know your customer/business’ procedures, according to risk

- account monitoring, according to risk

- records retention

- identification of suspicious transactions

- reporting of suspicions

- handling of customers under suspicion

- use of ‘material deficiency’ findings

- internal auditing and compliance monitoring

- pre-employment screening

- staff education and training.

4. Our policies and procedures must be living documents, which are updated regularly so as to remain relevant to new products and risk areas, and which are an integral part of the way in which each business is run.

5. The three themes complement each other. A strong culture of awareness amongst staff will make it easier for businesses to assume responsibility for compliance, just as the assumption of that responsibility will help develop the desired culture. Clear, relevant and up-to-date policies and procedures will help – and be helped by – both.

6. If you are in agreement with the above, the next step would be for us to have discussions with the business heads concerning this new strategy, before convening the first meeting of the AMG to agree a more detailed plan of how and in what order to launch and implement the various initiatives.

Sincerely, etc.

Example

CEO’s MEMO RE: BUSINESS RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING COMPLIANCE

To: All Business Heads [and e.g. COO]

| Re: | 1. Business responsibility for anti-money laundering compliance |

| 2. Launch of Anti-Money Laundering Group (AMG) |

The purpose of this note is to outline the responsibilities which you and your businesses bear in relation to the prevention and detection of money laundering and terrorist financing in [Name] Bank in [Country] , and to set out the terms of reference for a new senior management group which I have decided to form, to be called the Anti-Money Laundering Group (AMG), to assist in the planning and implementation of a comprehensive anti-money laundering strategy for [Name] Bank in [Country].

- Business responsibility for anti-money laundering compliance

Primary responsibility for compliance lies with the business, and not with the compliance officer/risk manager. As discussed with each of you individually, I view your responsibilities as follows:- To oversee the devising and implementation of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing policies and procedures suitable for your business, and to keep them updated and relevant to new products and changes to local laws and circumstances and international conditions.

- To ensure that these policies, procedures and laws are observed day-to-day, for example by rewarding compliance with them, and by punishing non-compliance.

- To ensure that a specific anti-money laundering objective (in the form attached at the Appendix) is included within your own personal job objectives, and that suitably adapted versions appear within the objectives of other key identified staff, with performance against this objective being included in annual appraisals.

- To ensure that anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing training is undertaken for all relevant staff, with a repeated emphasis being placed on the personal responsibility of staff members for the prevention and identification of money laundering.

- To appoint, in consultation with the compliance officer/risk manager, a specific person within your business, to act as a ‘Compliance Champion’ (this role may be ‘double hatted’ with their existing role), assisting the Compliance Officer/Risk Manager with various tasks such as training and the dissemination of relevant materials, information and resources in relation both to money laundering and to compliance generally.

- To ensure that relevant staff, when considering customers, business and transactions, give due consideration and weight to money laundering and terrorist financing risk. In particular, that they do not abdicate their own personal responsibility for ensuring the suitability of business.

- Launch of Anti-Money Laundering Group (AMG)

The AMG will be the senior body within [Name] Bank in [Country] for the management of money laundering and terrorist financing risk. Comprised of the heads of businesses, [the chief operating officer (COO)], the compliance officer/risk manager and myself, it will have the following terms of reference:- The broad objective of the AMG will be to implement an anti-money laundering strategy, specifically:

- to help create a ‘culture of awareness’ amongst staff within [Name]Bank in [Country], in relation to money laundering risk;

- to help embed responsibility for anti-money laundering compliance deep within the businesses of [Name] Bank in [Country]

- to help [develop] [maintain and enhance] effective anti-money laundering policies and procedures in [Name] Bank in [country]

- to help ensure that [Name] Bank in [Country] takes considered and appropriate action in response to [Name] Bank, national or international issues arising in connection with money laundering.

- The AMG will meet at least once every two months, or more frequently should it be required.

- The standard agenda for AMG discussions will be as per the document entitled AMGAgenda.doc, but other topics may be included as required.

- The broad objective of the AMG will be to implement an anti-money laundering strategy, specifically:

The first meeting of the AMG will take place on [date] at [time], when we will attempt to establish priorities and timings for the various initiatives.

In conclusion, I cannot over-emphasise the devastating effect which even inadvertent involvement in a money laundering and/or terrorist financing scandal would be likely to have on our business and reputation [in the current environment]. Nor can I overstate the critical importance of your providing firm leadership on this issue within your respective businesses [and functions]. I know I can count on you to work with me to ensure that our anti-money laundering strategy is a success.

Sincerely, etc

APPENDIX – FOR INCLUSION IN STAFF PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES

During the assessment period, actively to assist the Bank’s drive against money laundering and terrorist financing, and to provide business leadership on money laundering and terrorist financing prevention by:

- attending and contributing at the senior management AMG meetings

- implementing action points agreed upon and decisions made at AMG meetings

- punishing mistakes of non-compliance appropriately

- attending at and, where appropriate, introducing, staff training sessions on money laundering

- achieving a score of 80 per cent or more in the money laundering self-assessment test administered by compliance/risk management.

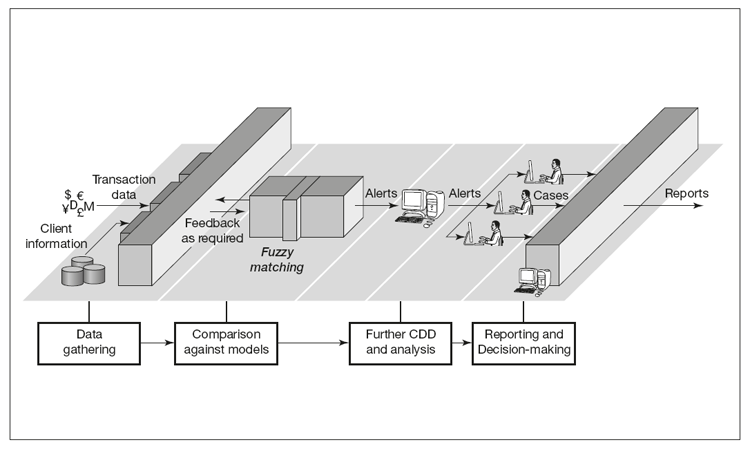

AML/CFT policies, procedures and systems

With the assistance of the AML/CFT Compliance Officer, businesses will need to implement complete policy, procedure and system solutions to the AML/CFT risks which they face. The precise scope and content of these polices, procedures and systems will be influenced by local law and regulation, but in order to comply with international standards they will need to deal with at least the following areas:

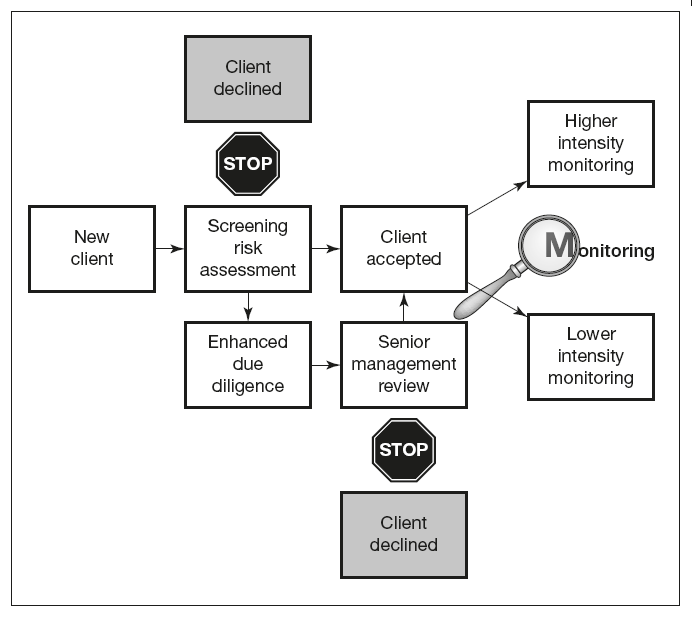

- Customer acceptance and black list screening. How the organisation takes on a new client and determines that the client is not on any international black lists.

- Client Due Diligence (CDD) and risk assessment. How the organisation checks that clients are who they say they are and how they determine the level of money laundering and terrorist financing risk posed by each client (see Chapter 4 for more detail).

- Know Your Customer (KYC). How the organisation builds its knowledge of each customer’s transaction and business pattern so as to be able to discern any unusual activity.

- Monitoring. How the organisation monitors its clients’ accounts for unusual and potentially suspicious activity.

- Suspicious transaction reporting. How the organisation detects and reports (internally and externally) transactions or relationships which are potentially suspicious (including its policies to deal with customers who are under suspicion).

- Mandatory reporting. If the law requires this, how the organisation reports transactions of a certain type or above a certain threshold to the authorities.

- Record keeping. How the organisation creates and stores customer records in accordance with national and international legal and regulatory requirements.

- Ongoing screening. How the organisation screens its existing client base on a regular basis to ensure that it is free of individuals and entities named on relevant lists of proscribed persons.

- Training. How the organisation raises awareness of AML/CFT risks and provides staff with the knowledge and skills necessary to combat them.

- Material deficiency findings. How the organisation detects, responds to and implements the findings of relevant international bodies (e.g. FATF, UN) in relation to areas or geographies of AML CFT risk.

- Staff screening. How the organisation screens key staff ahead of their employment for AML/CFT risk.

- Audit and assurance. How the organisation assures itself that the AML/CFT compliance function and policies and procedures are operating effectively.

AML/CFT BEST PRACTICE

The World Bank and the IMF have produced a guide to best practice, grounded in the original FATF recommendations and in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s international standards and this text is based on its consequential guidelines. In addition there is relevant guidance from other industry-specific bodies and relevant sources including IAIS (insurance), IOSCO (Securities), the Wolfsberg Group (international and private banking), the Joint Money Laundering Steering Group (UK consultative body) and the US Department of Treasury Anti-Terrorist Financing Guidelines (re charities), summarised in composite form below.

Customer identification and due diligence

The global KYC standard outlined here derives from the World Bank and IMF guidance and from the FATF recommendations together with associated regulatory guidance issued in countries such as the UK and US. The standard can be used as a benchmark for the banking sector, as well as a best practice reference point for other financial sectors.

How far should the KYC policy extend?

Whatever regime is introduced at the headquarters of an institution must be applied to its branches and to any majority-owned subsidiaries, both domestically and internationally, unless it clashes with local law in that jurisdiction. If there are differences in regulatory standards between home and host countries, then the more comprehensive/stronger of the two should be applied.

Who is a customer?

Banks need to establish at the outset whether the person with whom they are dealing is acting on their own behalf, or whether there is a beneficial owner of the account who may not be identified in their paperwork. If a bank suspects the customer is representing a third party, it must carry out due diligence on that third party as well.

Third parties may be organisations or legal entities as well as individuals. It can be particularly difficult to establish who the beneficial owner is when ‘tiered ownership’ is involved, with a whole pyramid of companies controlling one another and in some cases a parent company at the top. Again, appropriate due diligence is necessary in such a situation to find out the precise identity of the parent entity.

Customer acceptance procedures

It is necessary for banks to be able to identify which potential new customers represent a high risk in terms of money laundering and the financing of terrorism, by developing high-risk profiles against which they can be measured. Standard risk indicators for money laundering will include factors such as:

- the customer’s country of origin (e.g. from a country notified by the International Cooperation Review Group (ICRG) of the FATF, or a country habitually associated with the production, transit or processing of illegal narcotics)

- the type and country of business activity (e.g. arms, casinos, diamonds, jewellery, money exchange)

- any linked accounts, and whether or not they have a high-profile position and/or are ‘politically exposed’

- the kinds of products which the customer wishes to use, and whether they are of particular use to someone wishing to launder money (e.g. no notice restrictions on withdrawals).

As regards terrorist financing, it simply is not possible to produce a meaningful profile for an individual terrorist financier, but clearly issues surrounding the general profile of an account will be relevant, such as:

- known connections with a conflict area or country associated with terrorism

- business interests in or with such countries/areas

- frequent money transfers to and from such areas and travel to and from them (such as with associated charities and non-profit organisations)

- complex ownership structures leading back to individuals or businesses with connections to such places.

Senior management approval

The risk-based approach generally means that the bank can afford to exercise reduced due diligence with low-risk customers. The IMF/World Bank guidance recommends that the rigidity of the acceptance standards should be in proportion to the risk profile of a potential customer. However, when new customer business deemed to be ‘high risk’ is up for consideration, the onus should be on the senior management to make the decision as to whether or not such business is appropriate for the bank to take on.

Customer identification

Bank staff should verify any new customer’s identification to their satisfaction before an account is opened. Customers are not allowed to open accounts in fictitious names, and nor are numbered accounts permitted unless the usual customer ID procedures and supporting documentation are used as a matter of course.

Once they come to request identification documents, banks should ask for those that are hardest to forge. For individuals the most suitable are official documents such as passports, driving licences, personal ID cards or tax identification documents. An institution’s procedures should specify which of these or other documents might be acceptable for different individuals. For legal entities the suitable documents specified might include a certificate of incorporation, the business’s registered address, its tax identification number and whatever other proof of the business’s legitimacy as an entity is required.

When an intermediary – for example a trustee, financial adviser or nominee – is opening an account or carrying out a transaction on behalf of an individual or a corporate customer, then unless legally sanctioned ‘passporting’ procedures apply (e.g. as in the EU, where business introduced by other EU-regulated entities may be assumed to have been correctly identified already), the financial institution needs to take steps to verify the identification of the beneficiary. This will include the following information:

- the name and legal form of its organisation

- its registered or legal address

- the names of the directors and the principal beneficiaries

- the details of the agent acting on behalf of the organisation and the organisation’s account number with the agent

- the regulatory body to which the organisation answers.

There are sometimes legitimate reasons why a customer may not be able to provide preferred identification such as a passport or driving licence.

Since the purpose of customer identification is not to exclude legitimate customers from having access to financial services, an institution’s identification procedures should therefore include some alternative means of identifying customers to a satisfactory standard.

Detecting forgery

Particular care needs to be taken with the risk of forged identities, since this is a mechanism known to be used increasingly by terrorists, as well as criminal groups. For example:

- When dealing with a new customer face to face, it is important to check that the photo supplied is of the person actually opening the account, and that the date of birth given is realistic in the light of their appearance (an obvious point, but one easily missed in a frenetic retail environment).

- If bank statements from two financial institutions are presented as supporting evidence, check that the two show different transactions (one known method is to ‘cut and paste’ transactions to manufacture a second statement).

- Does the ethnicity of the name seem to match that of the customer?

- Is the content of each document consistent throughout (e.g. do the dates match)?

- Are the document margins straight? (Crooked margins are a red flag for forgery)

- Are there any other signs that the document has been tampered with?

Originator and beneficiary information on funds transfers

Funds transfers of any description should be accompanied by accurate and meaningful originator and beneficiary information – including name, address and account number – and that information should remain with the payment all the way along the payment chain.

Maintenance of KYC information

Knowing your customer is an ongoing exercise, which means that banks have to put some effort into keeping records up to date – for example if there are material changes in the way an account is run, or in the event of significant transactions being made on the account.

Low- vs high-risk accounts and transactions

As discussed above, the risk-based approach requires financial institutions to assess the AML and CFT risks attached to different types of customer profile. Similarly, financial institutions need to weigh up the potential for different kinds of product to be misused for criminal activities. For instance, a wire transfer service is a more obvious choice than a 90 days’ notice deposit account in this respect, (though long notice accounts can have their criminal uses too).

For lower-risk categories of customer (e.g. public companies or government enterprises) financial institutions may be able to scale down or simplify the due diligence requirements, for example by requiring fewer details about the business relationship or expected transactions. Nonetheless all customers, even lower-risk ones, should be required to prove and verify who they are. For higher-risk categories, banks should take additional precautions when they carry out customer due diligence. We look more closely at the various types of higher-risk customers, products and services in Chapter 4.

Record-keeping requirements

Minimum periods

As we have already seen, when intelligence services or regulatory authorities are tracing the evidence trail behind a money laundering or terrorist financing discovery, the availability of customers’ financial records (current and/or historic) can be a significant help in the detection and prosecution of the individuals involved. Moreover, the very fact that records are kept as a matter of course is believed in some cases to deter would-be criminals from their original illicit plans.

FATF Recommendation 11 sets a minimum international standard for the period over which banks and other financial institutions must retain records of the identification data obtained from customers (at least five years beyond the end of the customer relationship) and records of the customers’ transactions (at least five years beyond the date of the transaction). National regulation and institutional policy must therefore enforce this or a higher standard of record keeping. The regulators of any country may, of course, choose to extend the minimum five-year holding period for institutions based in their jurisdiction.

Type of information retained

The information retained by banks as a matter of course should include:

- a customer’s name, address and account number

- the date and nature of each transaction

- the currency and amount involved

- any other information that is routinely recorded by the bank and could be relevant in piecing together a criminal evidence trail.

Reporting obligations

Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs)

STRs are the mainstay of anti-money laundering programmes. They place the onus on financial institutions to spot suspicious or anomalous activities among the daily flood of transactions, and despite the difficulty in detecting financing activity at the front end of the terrorist financing chain, they have their place in countering terrorist financing, too. As FATF puts it:

‘If a financial institution suspects or has reasonable grounds to suspect that funds are the proceeds of a criminal activity, or are related to terrorist financing, it should ... report promptly its suspicions to the financial intelligence unit.’

Source: www.fatf-gafi.org copyright © FATF/OECD. All rights reserved.

However, a financial institution should, under no circumstances, alert the customers under scrutiny to the fact that their behaviour has been monitored and reported to the authorities.

Characteristics of suspicious activities

‘Suspicious activities’ can take numerous forms, but many will share certain broad-brush characteristics. Most obviously, as far as money laundering in particular is concerned, they tend to involve transactions out of step with the usual patterns seen on the account in question. So any complex or unusually large deals, or unusual transactions without any obvious commercial or lawful purpose, should be viewed as potentially suspicious and reported internally and, if appropriate, thereafter to the relevant authorities.

As far as terrorist financing is concerned, a variety of indicators may give cause for concern, ranging from problems with identification documents through to, for example, unusual signing arrangements, evidence of ulterior control by undisclosed parties, and wire transfer activity which shows signs of manipulation or structuring in order to evade reporting requirements or disguise ultimate sources of funds information.

Extent of reporting duties

How far does the reporting organisation have to go in its reporting duties? An STR simply comprises of the factual details of a transaction or series of events; there is generally no reason why the reporting bank, insurer or other financial institution should necessarily know anything about what it thinks may be wrong, only that it thinks that something may be wrong. Given that a United States’ Office of the Comptroller of Currency (OCC) guide identified more than 200 predicate crimes for money laundering, of which terrorist funding is just one, anything else would be an unrealistic expectation. In any case, anything more than initial attempts to try to clarify details by asking leading questions of the customer could amount effectively to a tip-off that their account was under scrutiny. Financial institutions’ obligations to report are therefore based on nothing more concrete than suspicions, and once they have filed an STR then any further investigation is generally left in the hands of the authorities, although reporting institutions may cooperate with the authorities in order, for example, to further their investigations and, hopefully, bring about successful prosecutions.

Currency transaction reporting

Given the enduring attractions of cash for money laundering or terrorist financing purposes, which in many ways goes against the global trend towards the use of plastic and the electronic movement of money, there is arguably a case for reporting any cash transaction above a certain threshold, on the basis that if everybody does it, such mass data can then be used for the purpose of trend analysis. The FATF Forty Recommendations go no further than suggesting that countries should consider the feasibility and utility of implementing such a regulation. Some jurisdictions have taken this step (including the US, Russia, and the countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union), but others have not, notably the UK and some other Western European Nations.

For example, the US requires that financial institutions record and report to the authorities any currency or bearer instrument transactions of $10,000 or more as a matter of course, and Australia has a similar A$10,000 threshold. The UK regime is entirely suspicion based, and has no automatic reporting threshold, although KYC procedures are required for one-off transactions above a €15,000 limit. The EU Third Money Laundering Directive extends this to cover other non-financial businesses such as casinos and estate agents, as well as anyone selling goods for which more than €15,000 is paid in cash.

Reporting obligations for transactions involving cash do apply across the board where same-day multiple transactions – known as ‘smurfing’ – occur. This process is used by money launderers as a means of avoiding a designated reporting threshold by breaking up the movement of cash into many smaller transactions. If smurfing is suspected, financial institutions need to report the entire series of transactions to the authorities, even though individually they do not breach any reporting threshold that may exist. Additionally, a single transaction could also be suspected on the grounds that the customer was trying to evade the reporting requirements, if it was for slightly less than the relevant reporting threshold. Again, in such cases the bank should look more closely at the transaction and file a report if it is suspicious.

Duty of confidentiality vs duty to report suspicion and/or other transactions

An important consideration as regards the whole principle of filing reports to the authorities on customer transactions is the concept of what are known in the US as ‘safe harbour’ laws. These are laws that protect financial institutions and their staff from criminal or civil liability arising from the alleged breaking of confidentiality or secrecy laws, provided they report suspicious transactions in good faith; that is, without malice.

Controls and independent audit

All organisations covered by a country’s AML and CFT laws need to set up their own internal policies and procedures to protect themselves against the risk of being criminally exploited in either way. A critical aspect of these internal controls is an independent audit function (whether based within the firm or brought in from outside), which is separate from the AML/CFT compliance function and therefore able to test objectively the adequacy of the overall compliance arrangements.

Staff training

Equally significant is the requirement for ongoing staff training. Whilst regular training programmes on how to recognise potential money laundering activity and what action to take have become a well-established feature of fully compliant financial institutions, much less attention is paid to the specifics of terrorist financing within the formal financial system. In the words of one (anonymous) senior compliance figure in the EU banking industry: ‘There’s not sufficient focus on terrorist financing generally. Banks should be able to point to specific CFT action that staff should take and training which they have undergone.’

Name screening

Prior to 9/11, the sanctions lists produced by international or national authorities focused mainly on specific countries or regimes, with the aim of prohibiting fund transfers to the sanctioned country and freezing the assets of the government, businesses and residents; or else they targeted known political figures (e.g. Slobodan Miloševićc). Since that date, the composition of the lists has changed, as thousands of individuals and organisations suspected of having terrorist links have been added to the lists.

Accessing and making effective use of the lists is a challenging operational requirement for all financial institutions. There are many sanctions lists available. The UN produces a broad global list, applicable to all member states, while the EU consolidated list comprises names featuring in the annexes to various EC regulations. In addition, individual countries may have their own domestic sanctions regimes.

For the US financial sector, the sanctions authority is the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). The OFAC list should include names listed under the UN sanctions regime, but it will not necessarily contain EU sanction targets. Use of the OFAC lists as well as the national and UN sanctions lists is necessary for all foreign financial institutions dealing directly with the US, and for this reason is generally undertaken by all large banks and indeed should be undertaken by any bank undertaking dollar business.

Pre-lists

In addition to these formal sanctions lists, from time to time the authorities issue warning lists of names deemed to be a source of concern to those institutions where those people are believed to have accounts, even though there are no legally binding sanctions attached at this stage. The purpose of the warning lists is to enable financial institutions to move immediately to freeze the target assets if or when these names are subsequently added to formal sanctions lists.

Initial and subsequent screening

Financial institutions are required to run all new accounts of any sort against the current updated versions of the relevant lists, and similarly to screen all existing accounts on a regular basis. Wire transfers should also be screened as a matter of course (see below) to establish that no person or entity whose name appears on a list is the recipient of the funds. It is a key operational responsibility for the AML/CFT Compliance function to decide which lists their organisation must watch and how often. This latter point will be a matter for each firm’s internal policy, and a reflection of its size and character. For instance, a small insurance firm might choose to scan its database monthly, whereas an international bank opening 10,000 to 20,000 new accounts each day would need to scan on a daily basis. Effectively this means that such institutions must have systems and software that can do this for them and there are a multitude of solutions on the market. Use of such systems is not mandatory under the EU Third Directive, although it is required of banks in the US.

Name match vs target match

Lists should contain any alternative name spellings and aliases used by the suspects in question, but of course it is not possible to conclude that just because someone has a name that features on a sanctions list, that they are the wanted individual. There is a distinction between a ‘name match’, where the organisation has matched the name of an account holder with the name of a target included on a list, and a ‘target match’, where the organisation is satisfied that the account held is that of the actual target of the financial sanctions, that is, the suspected ‘bad guy’.

Action when information is inconclusive

Full details of any target matches should be reported to the authorities and any affected accounts frozen immediately. However, it has to be said that target matches are a relative rarity. It is more likely that a name on the database will match with an entry on a sanctions list but there will be no conclusive evidence that it is the same person or organisation. In that case it is the financial institution’s job initially to look more closely at the KYC information and customer profile on record, and to assess it against the details available on the list. If it is not possible either to confirm or to clear the customer’s name on the basis of available information the financial institution may be able to seek guidance from the sanctions authorities, but in the meantime it is faced with the intractable problem of how to treat the customer’s account. Given the consequences and penalties of making a mistake, many financial institutions will take the view that they have no choice but to adopt the somewhat brutal policy of blocking an account until they have satisfied themselves that they do indeed only have a name match. They will prefer to deal with the customer’s lawsuit rather than a regulatory enforcement action or a criminal prosecution.

It is in these circumstances that the importance of painstakingly and diligently collected KYC information becomes all too clear, not to mention software programs that can analyse such data against list information and, for example, produce ‘target match’ probability scores.

Effective compliance with name screening requirements

As well as conducting the screening process on all new accounts, on existing accounts as often as is necessary and on wire transactions and one-off non-customer transactions, financial institutions need to establish and maintain an effective programme to ensure compliance with the sanctions authority in question. This should include:

- the existence and observance of written procedures for checking transactions against the relevant lists

- open communication lines between internal departments

- regular staff training

- an annual, in-depth audit of the compliance function.

Other considerations include arrangements for maintaining current sanctions lists and distributing them throughout every subsidiary or branch office, both domestically and overseas.

False positives

As well as situations where the available facts are inconclusive, there are also those situations where financial institutions will actually determine, erroneously, that their customer is the person named on the list – the dreaded ‘false positive’ scenario.

In such circumstances it is essential that financial institutions should be capable of demonstrating that even if the outcome was wrong, they followed their full and correct procedure and carried out checks with any other parties involved (e.g. with a remitting bank). It is vital to keep clear records of the decision-making process leading up to any action taken.

BEST PRACTICE IN HIGHER-RISK PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

As discussed earlier, one of the fundamental tenets of a risk-based approach is that financial institutions should make judgements about the risks of misuse attached to each relationship and should then focus the greater part of their attention in those areas where the greater risks lie. In this regard, specific attention should be paid to the following.

International correspondent banking accounts

Correspondent accounts may be maintained between banks, for use in making transactions for customers or between themselves. They are overwhelmingly above board, but certain cross-border correspondent arrangements are at risk of misuse by money launderers and terrorist financiers (the assumption being that due diligence and KYC will be dealt with by the respondent bank in the country of origin). Such accounts maintained with banks based in lightly regulated countries are particularly vulnerable, as they may offer a route for people or organisations to access the global financial system while sidestepping more rigorous checks.

As the IMF/World Bank guidance points out, before entering into such a cross-border arrangement, any financial institution should make an assessment of the respondent bank in question, establishing:

- its location

- the nature of its business

- the purpose of the proposed account

- the bank’s reputation

- the quality of its supervision

- the extent of its in-house AML/CFT policy and training provisions.

The importance of the above cannot be over-emphasised in the training provided to relevant staff. If ‘payable-through accounts’ are to be used, then the financial institution needs to ensure that the respondent bank will verify the identity of its customers and carry out ongoing due diligence on them. More generally, the respective responsibilities of the banks should be established and documented beforehand. Correspondent banking is another area where senior management should take responsibility for approving the business relationship before it actually gets going.

Banks should not set up correspondent banking arrangements with organisations located in certain FATF designated high risk jurisdictions, nor with so-called ‘shell’ banks (banks which are unconnected with any effectively regulated financial system and which are incorporated in a jurisdiction where they have no physical presence or actual staff operations).

Electronic banking

There has been a rapid and dramatic expansion in non-face-to-face business as a result of the development of financial information services and product delivery via electronic means, including ATMs, telephone and internet banking. Although there is no inherently greater risk involved in applications received by phone or internet than in, say, applications by post, a combination of other factors typically aggravate the risks involved.

For example, it is possible to make an application instantaneously, at any time and from any location; it is also easier to make multiple fictitious or anonymous applications without any additional risk and with less danger of detection. Physical documents are not typically required as part of the application process, therefore making it relatively easier to apply by using a stolen identity. All these factors increase convenience for criminals or terrorist groups, and correspondingly, the risks to financial institutions. However, FATF leaves it to individual jurisdictions to work out and put in place appropriate regulatory measures for their financial institutions.

The updated guidelines on customer identification provided by the UK’s Joint Money Laundering Steering Group (JMLSG) are an interesting example of the approach being adopted in some quarters. The JMLSG takes the view that:

‘The extent of verification in respect of non face-to-face customers will depend on the nature and characteristics of the product or service requested and the assessed money laundering risk presented by the customer ...

The standard identification requirement (for documentary or electronic approaches) is likely to be sufficient for most situations. If, however, the customer, and/or the product or delivery channel, is assessed to present a higher money laundering or terrorist financing risk – whether because of the nature of the customer, or his business, or its location, or because of the product features available – the firm will need to decide whether it should require additional identity information to be provided, and/or whether to verify additional aspects of identity.

Where the result of the standard verification check gives rise to concern or uncertainty over identity, or other risk considerations apply, so the number of matches that will be required to be reasonably satisfied as to the individual’s identity will increase.’

Source: www.jmlsg.org.uk

The guidance goes on to provide examples of the additional checks that institutions might use to mitigate, in particular, impersonation risk, but leaves it to the institution to determine how and when these will be applied Additional checks could take the form of, for instance (again, depending on the perceived risk presented by the customer), electronic checks as well as documentary evidence, or a written communication to the customer’s verified home address, or requiring a form to be completed and returned by post.

Wire transfers

Electronic transfers pose particular concerns for financial authorities and regulatory bodies. FATF’s Recommendation 16 and the Interpretive Note thereto sets out in detail the steps that financial institutions should take when sending money electronically:

- Subject to de minimis thresholds (which cannot be higher than US$/€1,000) cross-border and transfers should contain the names of both the originator and beneficiary and their account numbers used for processing the transaction (or a unique transaction reference number, if accounts are not used in processing), plus the originator’s address or national identity number or customer identity number, or date and place of birth.

- When a single originator bundles a number of transfers destined for various beneficiaries in another country into a single file, and sends them all together, there is no need to include full originator information on every transfer, provided that the batch file contains all the relevant originator and beneficiary identification details, as above.

- Domestic transfers must also include all the originator information, as above, unless the originating bank is capable of providing this on demand, in which case all that needs to accompany the money is an account number or some other effective means by which to identify the originator. ‘On demand’ means within three days of the originating bank receiving the request for information from the receiving bank or the authorities, as the case may be.

- Ordering, intermediary and beneficiary financial institutions all have responsibilities for ensuring that the requirements of R16 are met and for identifying and dealing appropriately with wire transfers which do not contain the necessary information.

Private banking

Private banking relationships are set up not only by wealthy individuals and Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) but also by law firms, investment companies, investment advisers and trusts. Particularly with regard to money laundering, private banking is viewed as a potentially high-risk sector of the banking universe for various reasons – not least because of the typical levels of wealth, the complexity and sophistication of financial services available (in particular, so called ‘secrecy’ products), and the number of advisers and intermediaries that may be involved in a client’s financial affairs. Often, too, the very purpose of starting a private banking relationship is to hide wealth and put it out of reach (whether from corrupt authorities, probing journalists or a vengeful spouse) – a process which is just as effective for criminal proceeds as it is for legitimate funds.

On the other hand, private bankers are likely to have more proactive and personal relationships with their client than would be the case in retail banking, and may therefore have additional insights into anomalous account activity. In this regard it is important to remember that the wealthy client issuing execution-only instructions for transfers of funds between various investments and offshore vehicles could just as easily be a terrorist sympathiser and financial donor, as a genuine client, or a criminal money launderer. Because private banking relationships can be so complex, it is also important that there are effective systems in place within each bank to monitor and report suspicious activity, and that this can be done based on a client’s total activities.

Standards for private banking have been largely driven in recent years by the Wolfsberg Group of international banks, which has drawn up a set of best practice guidelines for global private banking. These set out as the basic principle for client acceptance the requirements that banks will accept only those clients whose sources of wealth and funds can be reasonably established as being legitimate, and whose beneficial ownership is clear. It is the responsibility of the individual sponsoring private banker to make sure this is the case and, indeed, to be alert to suspicious activities on an ongoing basis. Importantly, say the Wolfsberg principles: ‘Mere fulfilment of internal review processes does not relieve the private banker of this basic responsibility.’ (www.wolfsberg-principles.com)

In addition, the principles address other key areas, as follows.

Client identification and due diligence

Crucially, client identification requirements under Wolfsberg extend beyond the actual named client to the beneficial owners of account assets. The private banker is expected to understand the structure of companies and trusts sufficiently to establish who are the main players involved, and they must make a judgement as to whether to carry out further due diligence on the individuals and companies concerned. Due diligence must include:

- the client’s reasons for opening the account

- the client’s expected levels of account activity

- details of the business or other economic activity that has generated the client’s wealth and an estimate of net worth (‘source of wealth’)

- details of the sources of funds to be paid into the account upon opening.

References or other corroboration of the details are also required, where this is possible, and it would normally be expected that a client would meet their banker face-to-face before opening the account.

Enhanced due diligence for higher-risk accounts

Extra caution is necessary, as would be expected, in cases where a client’s money was sourced in high-risk or lightly regulated countries, or where the client is involved in an area of business known to be susceptible to money laundering activities, or where the client is known to send funds to countries associated with terrorist activity or where the client donates to causes in such countries.

PEPs (who tend to favour the bespoke nature and privacy of private banking arrangements) also require additional due diligence (see below), and senior management must approve any new relationship with a PEP. Suspicious transactions (which may include large cash transactions, any account activity out of line with the customer profile, or ‘pass-through’ transactions) might be identified in a number of ways beyond the usual monitoring of the account. Suspicions might be triggered, for example, through third-party information from the media about a client, meetings with the client, or personal knowledge about factors such as the political situation in the client’s country. The onus, according to Wolfsberg, is on the private banker to keep abreast of the ‘bigger picture’, as well as gaining and maintaining a thorough knowledge of the customer and their situation.

Specific counter-terrorist financing principles

The Wolfsberg Group supplemented its original principles, which focused on money laundering and other financial crimes in relation to private banks, with a further statement on best practice dealing with countering terrorist financing. This highlights the importance of name screening:

‘The proper identification of customers by financial institutions can improve the efficacy of searches against lists of known or suspected terrorists [applicable to that jurisdiction].

To that end, it expands on existing identification, acceptance and due diligence best practice. Banks need to implement name-screening procedures and report any matches to the authorities; in addition they need to look at ways of speeding the retrieval of information about a customer if it is required.’

Source: www.wolfsberg-principles.com

Enhanced KYC policies should be in place for any customers involved in business sectors widely misused by terrorist groups, such as alternative remittance systems. Due diligence should be more extensive and rigorous on new business applications from such customers, and monitoring should be increased on both existing accounts and on those new accounts that meet the acceptance criteria. As a basic principle, banks should limit their business relationships with remittance businesses, exchange houses, bureaux de change and money transfer agents to those which are subject to appropriate AML/CFT regulation.

The Wolfsberg statement recognises that there is little chance that account monitoring will be able to identify individual transactions linked to specific terrorist attacks, but it emphasises the importance of continuing to look for and report suspicious transactions on the grounds that such information could provide leads for intelligence services. In particular, it highlights the need to scrutinise more rigorously the account activities of any customer involved with business sectors known to be a conduit for terrorist funds, and the need for banks to try to spot patterns and trends in terrorist financing.

Unusual/purposeless transactions

As well as monitoring the various higher-risk categories of business outlined above, the World Bank/IMF guidelines emphasise the need for financial institutions to be alert, across the spectrum of their customer accounts, to any complex, unusually large transactions, and to unusual patterns of transactions without any obvious lawful purpose.

They are instructed to look more closely at such transactions to establish as far as they can what is going on and why, and to keep a record of their findings. If they cannot obtain the information they want, or if their findings leave them still suspicious, they should consider turning the business away, and if necessary filing an STR.

Just as some kinds of financial services products are more likely than others to be exploited for illicit ends, so financial institutions are also expected to take a view on the likelihood that particular types of customer will pose a higher risk of involvement in criminal activity (including terrorist financing activity), and to adjust their due diligence, KYC and monitoring efforts accordingly.

Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs)

Among the categories identified by FATF, increased due diligence with regard to money laundering would be expected in the case of accounts for PEPs (senior people in prominent public positions and their families or close associates). Bank staff would be expected to identify the PEP and their sources of wealth and funds; any new account in the PEP’s name would have to be approved at senior management level, and more rigorous monitoring of the account would be required.

However, as the World Bank/IMF notes observe, ‘Actually finding out whether a customer is a PEP is often the biggest challenge for a financial institution.’ There is no official list of world PEPs to consult, for example, though ‘rich lists’ and other compilations are produced and updated commercially.

Business through intermediaries