KYC and the Risk-based Approach

Background to the risk-based approach

Components of the risk-based approach

Constructing a risk-based approach for your organisation

Example risk assessment frameworks

Constructing a CDD framework for financial institutions

Constructing a CDD framework for retail/consumer banking business

Constructing a CDD framework for private banking

Excerpts from Recommendations 1 and 10 of the FATF 40 Recommendations (February 2012) and the Interpretive Note there to:

‘countries should apply a risk based approach to ensure that measures to prevent or mitigate money laundering and terrorist financing are commensurate with the risks identified.’ (R1)

‘Financial Institutions should be required to apply each of the CDD measures ... above ... but should determine the extent of such measures using a risk based approach (RBA)...’ (R10)

‘There are circumstances where the risk of money laundering or terrorist financing is higher and enhanced CDD measures have to be taken. When assessing... money laundering and terrorist financing risks [relevant factors are] types of customers, countries or geographic areas, and particular products, services, transactions or delivery channels.’(R10 Interpretive Note)

www.fatf-gafi.org copyright © FATF/OECD. All rights reserved.

BACKGROUND TO THE RISK-BASED APPROACH

The requirement for a ‘risk based approach’ has generated probably the most radical overhaul in AML/CFT strategy to have been seen since the inception of global standards shortly after FATF was formed in 1989.

The so called risk-based approach, having been initially adopted within the economically developed nations which originally formed the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is now a general global requirement. It may be helpful for Compliance Officers in emerging markets (where AML and CFT standards may only have been adopted very recently) to understand not only the principles of its operation, but also its background. In doing so, they may better understand the industry and other pressures that are likely to confront the AML and CFT regimes put in place in their own countries.

Historically the various AML measures required by the original 40 Recommendations were not welcomed with open arms by the financial community. They were seen as bureaucratic and cumbersome, costly to maintain, not user friendly and hostile to good customer relations. In particular there were concerns regarding the ability of inflexible AML standards to distinguish between different types of customer, and it is this concern especially which the development of a risk-based approach has been designed to address.

For example, non risk-based principles would require a financial institution to treat a retired state pensioner in her seventies in the same way as a businessman in his forties receiving large funds from a country known for the production of blood diamonds. That is to say that, if one did not weigh the differences between these individuals, then the same identification, Know Your Customer (KYC) and account monitoring principles would apply to both of them, even though it is clear from a risk perspective that their profiles are entirely different.

Faced with the risks, what most countries and financial institutions ended up doing was applying a ‘one size fits all’ approach, which was viewed as being exceedingly harsh on the vast majority of customers who actually posed very slight money laundering risks. It also meant that scarce resources were not being applied as effectively as they might be in tackling higher-risk customers and relationships. By spreading the effort equally over all customers, it was argued that 90 per cent of that effort was in effect being wasted on the 90 per cent of customers who were very unlikely to have any involvement at all with crime or money laundering, with only 10 per cent of the effort being directed at the higher risk accounts (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 AML: the traditional approach

Would it not be better, so the argument went, if a risk-based system could be introduced which reversed these odds and enabled financial institutions to apply 90 per cent of their available resources towards the 10 per cent of their business which actually constituted the most serious risk? This would mean less bureaucracy, less paperwork, less form filling and of course a more welcoming experience for most customers (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 AML: the risk-based approach

It is of course the case that higher-risk customers tend to be (but are not always) wealthier, more international and worth more on an individual basis as customers. It is important to note, therefore, that from a business perspective the risk-based approach requires a considerable degree of finesse in its application to these higher-risk customers, so that they do not end up feeling that they are being discriminated against.

Pressure from the financial services industry within the developed economies led, in the early part of this century to discussions regarding a risk-based approach. These discussions manifested themselves first as proposals and then as revised recommendations and standards. Risk-based principles have now been embodied not only in the FATF 40 Recommendations, but also in other standards and in laws and regulations such as:

- the EU Third Money Laundering Directive

- the revised Wolfsberg principles

- the revised standards of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

- the national Regulations of all EU member states

- the USA Patriot Act, as amended.

COMPONENTS OF THE RISK-BASED APPROACH

Risk indicators

How do you decide whether a customer is high or low risk from a money laundering perspective? The FATF Recommendations refer to ‘customer risk factors’, ‘Country or geographic risk factors’ and ‘Product, service, transaction or delivery channel risk factors’ and then go on to list some relevant factors which create ‘potentially higher-risk situations’. From a practical perspective, a key requirement is a series of questions in relation to a number of important areas.

Type of customer

- Individual or business?

- High income or low income?

- Politically exposed or not?

- Introduced or brand new?

- Anomalous circumstances (e.g. geographic distance between financial institution and customer)?

- Non-resident?

- Corporate asset holding vehicle for an individual?

- Company with bearer shares or nominee shareholders?

- Complex ownership structure?

Type of business

- Which sector (industrials, trade, import/export, diamonds, arms)?

- Cash intensive?

- Does the business act solely for itself or does it represent others (e.g. investment or professional firms)?

- Type/identity of counterparties – which third parties is the customer doing business with and what is its risk profile?

Geography

- Where is the customer located (modern, developed country with advanced laws, or developing country with a developing legal system)?

- Is the customer a non-resident?

- In what other countries does the customer do business or have contacts?

- Is cash the normal medium of exchange within the country in which the customer is doing business?

- Is it a country known for the production of drugs or other high levels of criminal activity?

- Is it a country experiencing conflict or high levels of terrorist activity or insurgency?

- Is the country subject to sanctions or identified by credible sources as providing funding or support for terrorist activities?

Type of product and distribution channel

- What products is the customer using and how is access to those products being provided?

- Are those products more attractive or unattractive from a money laundering perspective (e.g. do they provide anonymity, such as with cash)?

- Do the products allow immediate access to funds?

- Do they allow for instantaneous international transfer of funds (e.g. SWIFT and telegraphic transfers)?

- Do they allow deposits to be made by third parties?

- Does the product facilitate the disguise of customer identity and transaction ownership (e.g. special use accounts, omnibus accounts, bearer instruments, beneficiaries, etc.)?

- Is the product distributed directly to the customer by the financial institution’s branches, or via a network of independent salespeople/intermediaries?

- Does the product attract customers without face-to-face interaction (e.g. via the internet)?

- Does the product provide enhanced levels of discretion and security (e.g. private banking)?

Transaction types

- Are transactions on the accounts typically in very high amounts?

- Is there an especially high transactional volume?

- Are they ‘payable through’ transactions (i.e. where the account is neither the originator nor the ultimate beneficiary)?

- Are the economic reasons for the transactions clear and justifiable (e.g. bill payment, purchase of goods, etc.)?

All the above indicators will affect a particular relationship’s susceptibility to money laundering and terrorist financing. Under the risk-based approach, what financial institutions then need to do after risk analysing their customer relationships, is to design and implement management and operational controls that are appropriate for and commensurate with the level of risk identified.

MITIGATING CONTROLS

In management and operational terms there are various aspects of policy and control that can be adjusted according to perceived risk levels, with more stringent, enhanced controls being applied to higher-risk relationships and less stringent, simplified controls being applied to lower-risk categories.

Identification requirements

For lower-risk relationships, a single form of identification and address verification may be appropriate. For higher-risk relationships, a greater degree of background research (and corresponding supporting documentation) as to identity, history, residence and other aspects of a customer’s identity may be deemed necessary.

Management approvals required for customer acceptance

If a customer is categorised as low risk, there ought not to be any need for senior management approval before they are accepted as customers. For higher-risk customers, however, the approval of more senior management may be appropriate and necessary and for the highest-risk customers, it may even be appropriate for the board of directors to sign off on the account.

Due diligence and KYC information

If a customer is in a lower-risk category, there may be very little point in making extensive enquiries about their background, the nature of their income and their activities and operations. For higher-risk customer groups, however, these types of enquiries make a great deal of sense because they increase the financial institution’s understanding of the customer and hence its capability to detect unusual and potentially suspicious behaviour. Enquiries might relate to, for example, further information on the nature of the business relationship, source of wealth, the reasons for intended and performed transactions, etc.

Frequency and depth of account monitoring activity

For lower-risk customers it may be appropriate to do virtually no monitoring at all. For higher-risk categories more frequent monitoring is required, the depth of which may also vary according to perceived risk. For example, sample sizes can be increased and transaction thresholds reduced to provide closer monitoring. In the highest-risk cases it is possible to conceive of 24/7 monitoring, but at those extreme risk levels one would have to query whether a relationship should exist at all.

Audit/independent testing

The audit level of the three-line defence model described in Chapter 3 should be adjusted according to risk. For example, higher-risk businesses should be audited with greater frequency and to a greater width and depth of sampling than lower-risk businesses.

Communication, training and awareness

Within the overall control environment it would be appropriate to focus greater resources on training and awareness within higher-risk business units at the justified expense of those businesses deemed to be lower risk, provided that all statutorily required basic training requirements for the organisation have been covered.

REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

The risk-based approach effectively represents a trade-off between regulated firms and regulators. In return for a more business focused, less bureaucratic form of regulation, financial institutions have accepted a greater burden to analyse risks effectively and act accordingly. The implication is that if they fail to do this then the censure and punishment they face will be even greater than before.

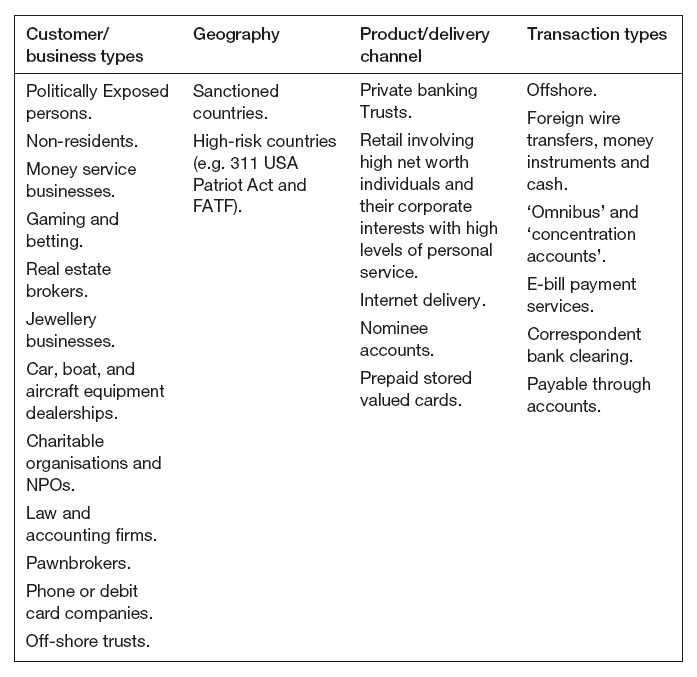

Table 4.1 shows an example of what one particular financial institution considered to be high-risk characteristics from an AML perspective. Read the categories and then take a moment to consider how appropriate it is for your own organisation. Consider whether there are any items that you would add or delete from any of the columns with regard to your own business.

Table 4.1 High-risk characteristics

SPECIAL CATEGORIES: POLITICALLY EXPOSED PERSONS (PEPS)

A category of high-risk customer that receives particular attention in the various international standards and guidelines (FATF 40, BIS, Wolfsberg, EU Third Directive, USA Patriot Act) is that of Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs). PEPs are defined in the FATF 40 recommendations (interpretative notes section) as follows:

‘Foreign PEPs are individuals who are or have been entrusted with prominent public functions in a foreign country, for example heads of state or of government, senior politicians, senior government, judicial or military officials, senior executives of state owned corporations, important political party officials. Domestic PEPs are individuals who are or have been entrusted domestically with prominent public functions, for example heads of state or of government, senior politicians, senior government, judicial or military officials, senior executives of state owned corporations, important political party officials.

Persons who are or have been entrusted with a prominent function by an international organization refers to members of senior management, i.e. directors, deputy directors and members of the board or equivalent functions.

The definition of PEPs is not intended to cover middle ranking or more junior individuals in the foregoing categories.’

Source: www.fatf-gafi.org copyright © FATF/OECD. All rights reserved.

Why are such figures considered higher risk from an AML perspective? The reasons stem mostly from the high profile that such individuals hold. They tend to attract a great deal of interest from business people, some of whom may have criminal connections or may even be criminals themselves. They often have substantial decision-making powers (or, in democratic states, the prospect of obtaining these powers through the political process) including the power to allocate vast state funds to particular companies through the award of government contracts. This therefore makes them vulnerable to bribery and corruption. In the worst instances, they may even themselves be of a criminal disposition whereupon they will be well placed to misappropriate public funds. Finally, of course, by virtue of their positions they are likely to be in possession of sensitive non-public information which could enable them to benefit in a criminal manner at the expense of others (e.g. insider trading), should they choose to use it that way. And because PEPs are aware of the scrutiny which their activities are likely to be subject to, they may use family members, associates and, completely unknown ‘fronts’ as conduits through which to conduct their transactions and escape scrutiny.

Recommendation 12 requires that financial institutions should, in relation to both foreign and domestic PEPs, and in addition to performing normal due diligence measures, have appropriate risk management systems to determine whether the customer is a PEP. Once such a determination has been made, then in relation to all foreign PEPs and in relation to domestic PEPs whom they have assessed as being higher risk, financial institutions should:

- obtain senior management approval for establishing business relationships with such customers

- take reasonable measures to establish the source of wealth and source of funds, and

- conduct enhanced ongoing monitoring of the business relationship.

Clearly, the capability of an organisation to determine whether a prospective customer is a PEP is an important one. But how do you determine whether an account holder is a PEP? There are various methods available:

- Seek information directly from the individual.

- Review sources of income including past and present employment history and references from professional associates.

- Review public sources of information (e.g. databases, newspapers, microfÎche records, etc.).

- Check the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) online directory of ‘Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments’ (www.odci.gov/cia/publications/chiefs/index.html).

- Check the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index.

- Check private vendor sources (e.g. World Compliance/Regulatory DataCore (RDC), Factiva and WorldCheck).

CONSTRUCTING A RISK-BASED APPROACH FOR YOUR ORGANISATION

Basic model examples

The risk-based approach (as described above) is already a regulatory requirement in many jurisdictions and will progressively spread to all jurisdictions, as they move towards full compliance with international AML and CFT standards. Care needs to be taken that risk-based solutions which are in keeping with international standards are nevertheless still consonant with national regulatory requirements.

Conceptually, it is helpful to think of the process of designing risk-based controls in terms of having two dials, X and Y. The X dial is connected to antennae capable of gathering relevant information and it records risk according to the various criteria discussed above. The Y dial is adjustable and sets control levels. It can be calibrated, according to the risk information received from the X dial, so as to provide the optimum control environment for the institution. This model is depicted in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Risk-based approach assessment and control model

In terms of risk assessment, clearly organisations must be able to harness as much high-quality information as possible in order to make a meaningful assessment of risk. Questionnaires, therefore, for completion by the customers themselves or by bank staff, paper-based or electronic, will be an important medium through which information about the customer is acquired. Other important data-gathering media include well structured interviews, background research (where this is justified) and, in extreme cases, private vetting via investigations agencies (more on this in Chapter 5, which deals with the subject of reputational risk).

Information about the customer needs to be married with an assessment of the product risk and country risk, as discussed above.

Product risk assessment – test your instincts

What makes a product more or less risky from an AML and CFT perspective? We looked at some of the features earlier on and now we will try to put these into practice. Below are some product descriptions from different areas of financial services. Look at these descriptions and for each product assess whether you consider that product to be either higher or lower risk.

Banking

Product: Personal current account – high or low risk?

Product: Personal current account

Description: Ordinary account for daily living

Surrender/withdrawals: Yes

Payment methods: Cash, cheque, draft or transfer

Third-party payments: Yes

Additional payments: Yes

Minimum periods: None

Complex structures: Possible

International: Possible

Other controls: Identification requirements on account opening

This product may be high risk for placement and layering activity, but will only normally be considered high risk if the amounts going through it are large. It satisfies many of the launderer’s requirements. It can receive money, in cash if needs be, and from third parties, and send it anywhere in the world to other third parties. There are no limits to the amounts which can be put through it (subject to staff suspicions) and no minimum periods or lock-ins.

Product: Letter of credit/documentary credit – high or low risk?

Product: Letter of credit/documentary credit

Description: Trade finance product through which bank pays exporter for goods and reclaims funds from importer

Surrender/withdrawals: Yes, value is exchanged at the point where bank accepts reimbursement from importer

Payment methods: Cheque, draft or transfer

Third-party payments: Yes

Additional payments: No, but multiple credits possible for single clients

Minimum periods: None

Complex structures: No

International: Yes

Other controls: Fraud controls on import/export documents

These products are lower to medium risk within the banking sector due to the fact that a customer will have to undergo intrusive scrutiny (e.g. credit checks) to discover whether it is a proper trading company, or through a registered office visit to verify that the business is as it claims to be. Letters of credit can be and are used for money laundering (typically layering), despite being vulnerable to discovery from vigilant trade clerks who may e.g. recognise that the import documents are fake.

Product: Credit card – high or low risk?

Product: Credit card

Description: Running credit account based on point-of-sale credit transactions, with balances and/or interest repaid monthly

Surrender/withdrawals: Yes, value is exchanged at the points where (1) goods and services are purchased, and (2) debit balances incurred are repaid

Payment methods: Cash, cheque, draft or transfer, but amounts are usually small, less than €5,000.

Third-party payments: Yes, but would be considered unusual

Additional payments: Yes, payments are made monthly

Minimum periods: None

Complex structures: No

International: Yes

Other controls: High predictability of profile on most accounts allows easy identification of unusual card usage

Credit cards are lower risk because they are not as flexible as, say, a current account (you can do fewer things with them.) But they can be used by criminals at the integration stage – particularly at the platinum end of the market – for unlimited spending, with funds of criminal origin used to repay the card. Credit card frauds can also be used to finance terrorist attacks.

Product: Corporate treasury foreign exchange services – high or low risk?

Product: Corporate treasury foreign exchange services

Description: Conversion and transfer of currency deposits, both for trade/commercial purposes and as part of speculative/trading strategy. Often large sums involved (more than €1 million)

Surrender/withdrawals: Yes

Payment methods: Cash (rare, given amounts), cheque, draft or transfer

Third-party payments: Yes

Additional payments: Yes

Minimum periods: None

Complex structures: Often

International: Yes

Other controls: Services often offered only to limited pool of well-known institutions

These products are higher risk, given the large sums involved and the international nature of the business, allowing substantial cross-border payments to be made to and from an account. The Risks can be mitigated by limiting availability, as above.

Fund management

Product: Hedge funds – high or low risk?

Product: Hedge funds

Description: Non-discretionary investment for sophisticated investors with high-risk appetite (e.g. may involve derivatives trading and short selling)

Surrender/withdrawals: Yes, but usually a lock-in for a set period (e.g. five years)

Payment methods: Bank draft or electronic transfer

Third-party payments: Yes

Additional payments: Yes

Minimum periods: Five years and beyond

Complex structures: Yes

International: Yes

Other controls: No

These products, are higher risk, due to the fact that they allow a diverse range of investors, as well as the use of complex investment structures and some offshore tax havens with a lower degree of regulatory scrutiny.

General insurance

Product: Personal household insurance – high or low risk?

Product: Personal household insurance

Description: Household insurance for contents and buildings insurance

Surrender/withdrawals: Upon a claim

Payment methods: Monthly or annually

Third-party payments: By the broker

Additional payments: For increases in contents liability

Minimum periods: Annually

Complex structures: No

International: Possibly, subject to permissions in the overseas country

Other controls: Fraud claims. If payment stops so does policy.

This would be low risk, due to the fact that payout only occurs after assessment. Also a police crime reference number has to be provided. If premiums cease so does the cover. Fraud controls will also be in place.

Adjusting product controls to the overall level of the relationship risk

As we have seen, AML and CFT risk is about more than just the product. It also encompasses the type of customer, geographic issues and business issues. In order to make the risk-based approach work, organisations need to construct methodologies for applying particular control regimes to a particular type of risk – assessed relationships. At a basic level, one can imagine a process as follows:

- consider product, distribution channel, customer and domicile

- consider whether high-risk elements shift the relationship into a higher-risk category (e.g. a high-risk customer using lower-risk products)

- adopt increasing control strengths according to whether a relationship has been assessed as either ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’. For example:

- Low risk = A + B (i.e. minimum legal requirement of customer identification (A) and address verification (B))

- Medium risk = A + B + C (i.e. identification plus address verification plus source of funds check (C ), i.e. where the funds have originated from – e.g. bank, private account)

- High risk = A + B + C + D (i.e. identification, address verification and source of funds check as above, plus source of wealth check (D), i.e. what economic activity has generated the customer’s wealth?)

Monitoring activities are also adjusted accordingly, such that very limited monitoring takes place on low-risk accounts, more monitoring takes place on medium-risk accounts and very frequent monitoring occurs on high-risk accounts.

It is important to note that a low-risk product could be placed in a higher-risk category if the customer is perceived as a high risk (e.g. a politically exposed person using a credit card).

Relationship risk classification – test your instincts ...

Using the above methodology, we can now review some relationship examples and try to ascribe a risk assessment rating (low, medium or high) and a corresponding control regime (A + B; A + B + C; or A + B + C + D) to each example. Note that at this stage we are not using a consistently applied calculating mechanism (that comes later). Rather, we are exploring how different combinations of customer, product and geographic risk factors affect our assessment of risk and the different control responses required accordingly,

Scenarios

Scenario 1

An individual customer from a FATF member country wants a credit card, which will be repayable from their current account at an EU regulated financial institution. The predicted average monthly spend on the card will be around €800.

This scenario involves a low-risk product, a low-risk customer, a low-risk jurisdiction, with low regular payments from a regulated financial institution in a low-risk jurisdiction = a low-risk relationship. So A + B would be appropriate – identity check and address verification, with the least intensive monitoring.

Scenario 2

A government official from a highly corrupt country wishes to open a numbered deposit account with your private bank, with the initial funds being transferred from the accounts of nominee companies owned by him in various offshore locations, some of which have been associated with tax evasion. The initial expected receipt is for US$2 million.

This scenario involves a high-risk product, a high-risk customer, a high-risk jurisdiction, a very large initial deposit (given the applicant’s occupation) = a high-risk relationship. In fact, even allowing for A + B + C + D (identification, verification, source of funds and source of wealth checks) – query whether you should be doing this business at all unless you can get some compelling evidence on the legitimacy of the applicant’s source of wealth.

Scenario 3

A trading company wishes to open letters of credit for products being exported from a FATF country to a neutral country (i.e. neither FATF nor ICRG). Payments under the credits are to be received from the importer’s local bank. The products in question are perfume and certain other fancy goods.

This scenario involves a low to medium-risk product, a low-risk customer, and a medium-risk counterparty (the paying bank) from a medium-risk jurisdiction = a medium-risk relationship. So A + B + C would be appropriate – identity check, address verification and source of funds check. You would also need to conduct due diligence against the importer’s bank.

Scenario 4

An established institution from a FATF country wishes to make a medium-sized investment in one of your property funds (an investment fund containing a portfolio of commercial property and producing income from rental streams and profits on sales from properties located in the EU, the US and Hong Kong; investment range from US$10m to 25m)

This scenario involves a relatively low-risk product, a low-risk customer, low-risk jurisdictions and a moderate investment sum = a low-risk relationship. A + B only are appropriate – identity check and address verification, with minimal monitoring

Scenario 5

A previously unknown firm of investment consultants from an offshore tax haven states that it represents a group of international private investors with a high-risk appetite and a very large amount of money for investment in your best performing hedge fund.

This scenario involves a high-risk product, a high-risk customer, a high-risk jurisdiction and large investment amounts = a high-risk relationship. A + B + C + D is required – identity check, address verification, source of funds check and source of wealth check.

Taking it to the next level of detail

Figure 4.4 Digging deeper for information

Building upon the principles outlined in this chapter, you should think of due diligence as a process of digging for information (see Figure 4.4). If a relationship is very straightforward and low risk, then you’re not expected to dig very deep and a simplified form of due diligence (denoted as Simplified Due Diligence – SDD Figure 4.4) will be appropriate, involving only a restricted number of the information elements listed above. Depending on the business profile of your institution, this may actually be a relatively small minority of the overall number of customer relationships. There will then be those customers and relationships where the risks are of a medium nature with much more digging required in many more of the key information elements listed above (designated as Normal Due Diligence – NDD). Again, depending on the specifics of the institution’s business profile, this category may turn out to encompass a significant majority of its overall customers and relationships.

Finally, there will be those relationships which are classified as high risk, for the various reasons that we identified earlier on in this chapter. These will require the greatest depth of digging. The purpose of this digging is not just to increase the chances of identifying information and previously unknown risks that may affect your decision to take the customer on or affect your treatment of them, if you are already in a relationship with them; The digging also ensures that you can demonstrate to the world at large that you took greater precautions when you perceived higher degrees of risk. For these high-risk relationships the full range of information types outlined above would need to be collected. This level of quite intensive ‘digging’ is designated as Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD in Figure 4.4).

THE CORE COMPONENTS OF CDD

Information collection

Whatever risk assessment framework you are operating, the due diligence which your company undertakes will comprise the base level elements of information collection and information verification.

The type of information which it may be relevant to collect for due diligence purposes is wide ranging. Details could be required, for example, in relation to any or all of the following.

Personal information

- Name – including any aliases, shortened versions and variations in the order of the words in the name (e.g. ‘John Vey Atta’, also known as ‘Atta John’ or ‘Vey John’).

- Address – including alternative addresses where these exist.

- Date of birth.

- Nationality.

- Occupation.

- Source of funds – i.e., the location (country/city) and bank or other institution from which funds entering the account have originated.

- Account purpose – the reason why the account is being opened (e.g. to receive salary; to purchase a new car; to set aside funds for investment, etc.). This is a critical piece of information which, all too often, is completed by relationship managers in insufficient detail. Answers which the author has seen on customer acceptance documentation have included ‘general’, ‘N/A’ and even ‘bank account’.

- Anticipated account activity – i.e. the types, size, volume or frequency of transactions anticipated to take place on the account.

- Source of wealth – the economic activity which has generated the funds or other assets which the institution is handling for the client (e.g. inherited wealth, wealth from the sale of a business, investment income, etc.).

Personal information of a corporate nature

It is not just for personal accounts that you may need to obtain personal information. Individuals obviously hold or perform key positions and functions in corporations and other legal entities, in which case the following information may be required:

- Names and identities of directors and partners.

- Names of registered and beneficial owners holding (25 per cent or more significant percentage of the shares or voting rights in an entity) (‘Beneficial owners’ may not appear on share registers, and are natural persons – not corporate entities – who ultimately own or control the entity, or for whose benefit or on whose behalf transactions are conducted).

- Names of all authorised signatories.

- Names of settlers, trustees and beneficiaries.

Corporate (non-personal)

Finally, there is information about the customer entity itself when it is an artificial person, such as:

- Name.

- Registered number/tax identification number.

- Type of entity – e.g. private corporation, public/state-owned entity, partnership, etc.

- Registered office.

- Business address (if different).

- Country of incorporation.

- Purpose of account.

- Anticipated account activity.

- The nature of the business – i.e., the business sector in which the entity is involved and any specialist products or services it provides.

- Countries where the entity conducts business – this would include, for example, export destinations and import origination, as well as details of overseas offices and branches, with special reference to high-risk countries and countries which are a subject of sanctions.

- In case of financial institutions, information on internal AML and CFT policies and controls.

- Details of reputation in terms of corporate activity.

- Quality of supervision.

- Reason for opening account.

- Source of wealth.

All of the above adds up to quite a lot of information and would impose significant burdens on most institutions if all of that information had to be collected in each and every case. Thankfully, because of the application of risk-based principles, this isn’t necessary.

Verification

What do we mean by ‘verification’? Verification refers to the process by which we provide proof or reassurance that a piece of information is true.

If your institution has account opening discussions with a representative of a company who tells you that the name of the company is Bertoli Communications Ltd, how do you prove it? Because remember, if you didn’t prove it and the company was actually a different company or, more likely, non-existent, then money could be laundered through its accounts, those accounts could be emptied, everybody would disappear and there would be nothing left to go on.

If the representative of the company tells you that its business is the import and export of mobile phones and other electronic communications equipment, how do you prove it? If you don’t, then it’s possible that it could be a shell company and that all the activity on its account represents money laundering.

If the representative tells you that the beneficial owners of the company are Mr X and Mrs Y, how do you prove it? Because if you don’t, how can you say that the company isn’t owned by an organised crime syndicate or a corrupt politician?

Verification doesn’t stop accounts and relationships being used for money laundering, but it is an important barrier, an inconvenient additional hurdle which criminals and launderers must overcome if they are to achieve their objectives.Verification involves the collection and retention of evidence in the form of official documentation (e.g. passports, constituent documents of companies and other artificial legal persons, print-outs from websites), certification (e.g. certifying copies as being true copies of originals which have been sighted, and stamping documents as such, obtaining official letters from embassies, notaries, solicitors or attorneys regarding the truth and reliability of documents and copies of documents), reportage (e.g. a report prepared by a relationship manager of a visit to an address, confirming that the company is actually operating a business from that address) and electronic data (with the emergence of the data-driven economy over the past 10 or so years, increasingly now in a growing number of countries there are reliable, independent databases which can serve as a means of electronic verification of, for example addresses and telephone numbers against names and dates of birth).

The extent of information verification will, like the collection of the information itself, be undertaken on a risk-sensitive basis. The higher the perceived level of risk, the more extensive the degree of verification that is required. As we shall see, in the highest-risk relationships involving, say, politically exposed persons or companies operating in very high-risk sectors or countries, the required information and verification levels may be quite extensive and will involve asking lots of questions and checking the answers against a wide range of documents such as trade agreements, financial returns, solicitors’ letters, press articles, business sale agreements and property deeds. There are also multiple sources of publicly-available information which can be used to check the consistency of information which has been provided to you, though it should be remembered that the easier it is for the information provider to manipulate such sources, the less reliable they are. Examples include:

- company website and literature

- newspapers and other media (including their websites)

- industry magazines and websites

- local and industry contacts and other third parties

- subscription information services such as WorldCheck.

In certain situations (which we explore in more detail in Chapter 5), it may prove necessary to instruct external agencies and consultants to conduct investigations against individuals and companies in order to establish their bona fides.

Long gone are the days when it was acceptable to ‘take a gentleman at his word’.

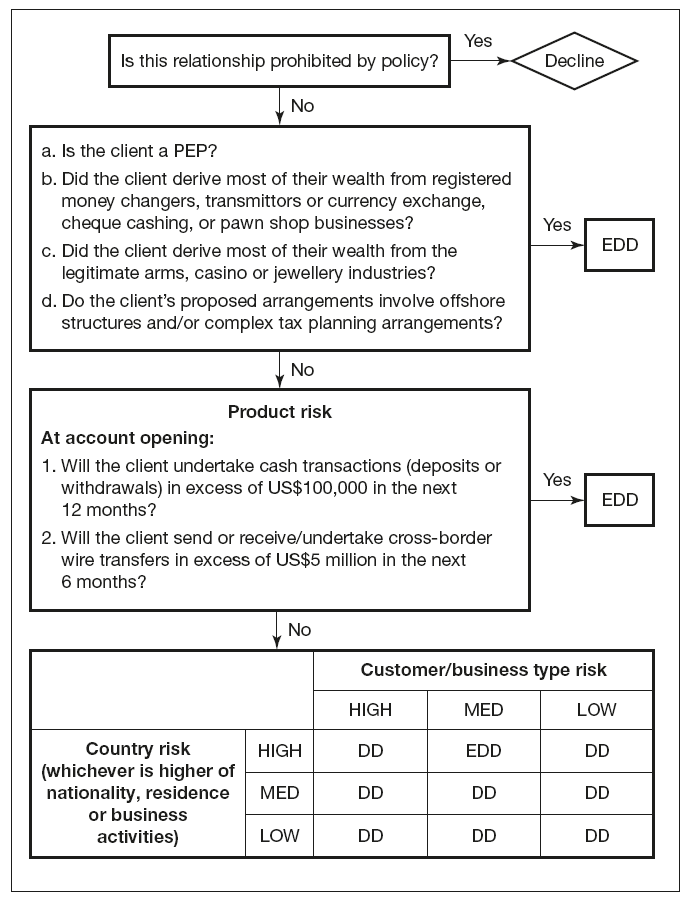

CDD PROCESSES AND TOOLS

In the wholesale/corporate, financial institution, retail/consumer and wealth management/private banking example processes which follow, I have suggested a common framework and some common tools with which to inform a tactical approach to implementing the broad principles of the risk-based approach. This framework is shown in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5 Example CDD process

Figure 4.5 echoes the earlier generic client acceptance process flow described in Chapter 3. At various stages, systems, procedures and controls must be in place to enable your institution to:

- screen applicants for business against a company watch-list of prohibited entities and prohibited account or relationship types

- reach meaningful assessments of country, customer and product risk

- classify relationships into one of three categories which I have designated as simplified due diligence (SDD), normal due diligence (NDD) and enhanced due diligence (EDD)

- calibrate information, verification, approval levels, account monitoring and audit intensity according to the level of perceived risk

- review relationship activity on an ongoing basis (again, risk-sensitive) and recalibrate where necessary.

Unacceptable clients and relationships tool

Apart from your institution’s alert-list requirements, a key tool during the screening stage of the process will be your list of unacceptable accounts and relationships. This will be based upon both generally accepted practice and your company’s own risk appetite based upon its own experience (things which have gone badly, gone well or could go well if they were managed differently, etc.).

Here is an example of one such list:

Example: Institutional list of unacceptable accounts/relationships

- Proscribed entities

- Shell banks

- Unlicensed banks

- Unregulated money service businesses

- Customers with known or suspected involvement in money laundering, terrorist financing, WMD proliferation or tax evasion

- Anonymous or numbered accounts

In other words, this is your institution saying to the world: ‘We are not even going to go to the trouble of assessing risk here, we simply will not do this business – ever.’

Country risk list tools

Clearly you cannot rely on individuals or business units to make their own assessments of money laundering and terrorist financing risks in different countries on an ad hoc basis. They will need a list, updated regularly, which designates every country in the world as either low risk, medium risk or high risk for money laundering, terrorist financing and, latterly, for international tax compliance and proliferation financing. There are companies and commercial websites selling consultancy services and collated publicly-available information that can assist you in determining which category a country should fall into. This is also something which you and your institution should spend some time thinking about. Relevant factors include:

- economic sanctions

- presence on the FATF ICRG list

- offshore status (and if so, current status on the OECD managed tax information exchange agreement process)

- any Moneyval, WorldBank or IMF mutual evaluations or assessments of the strength or otherwise of the country’s AML regulatory regime

- membership of bodies such as the FATF or its regional sub-groups

- membership of the EU

- political unrest, war, insurgency or terrorist threat

- whether a producer or transit country, for example, narcotics, people trafficking or smuggled goods such as weapons, alcohol and tobacco

- any specific features of its financial services industry which make it higher risk (e.g. tax advisory, nominee/trust companies, private banking)

- any institution specific incidents or beliefs relating to that country (e.g. based on knowledge of local business practices).

Country risk lists, particularly those from governmental or regional institutions, are obviously immensely useful in assessing the comparative risks of different jurisdictions. However, the fact that a country is listed on a ‘low risk country’ list is no guarantee that business within that country is automatically low-risk. For example, in the EU a ‘Doctrine of Equivalence’ applies to all member states. In effect what this means is that member states are assumed to have common AML and CFT standards and are therefore entitled to be labelled as ‘equivalent’ jurisdictions. If a jurisdiction is labelled as an ‘equivalent jurisdiction’ then this is usually taken as a heavy pointer towards lower risk assessments for customers based in that country, with all the attendant benefits (cost and time-wise) of lower due diligence levels. Indeed, most EU-based financial institutions carve out a special place in their country risk assessment lists for EU equivalent jurisdictions. But it’s important to remember that just because a country is an EU member state doesn’t automatically mean that financial institutions will necessarily be rating it as ‘low risk’. For example, for different reasons, a number of financial institutions rate Luxembourg and Greece as ‘high risk’, even though they are EU member states and equivalent jurisdictions. Likewise, most financial institutions rate Russia as ‘high risk’ even though it is a member country of the FATF. People form their own judgements and so should you and your institution.

Table 4.2 shows a sample example a country risk-assessment sheet, followed by a list of equivalent jurisdictions in Table 4.3.

Business sector risk tool

Again, your business units will need policy guidance on this, as individual perceptions of risk will differ. What makes a business high- or low-risk for money laundering and terrorist financing purposes? To answer that question one must look at how attractive certain business types are for those who wish to launder money or finance terrorism. Clearly cash-based businesses are attractive for the reasons we have identified earlier, as are any businesses involved in the transmission of money for other people. Import and export companies with a valid business reason for remitting and receiving large sums in their normal course of business will also be high risk for their ‘cover’ potential for money launderers, and we know that the real estate sector also offers attractive opportunities for money laundering. Religious organisations, charities and non-profit organisations (NPOs) are high-risk for terrorist financing.

Table 4.2 An example country risk tool

Table 4.3 An example jurisdictions tool

In terms of medium risk, these would be business types which have some potential for money laundering and which, whilst not offering the same level of attraction as the high-risk business sectors above, nevertheless are known to have been involved in money laundering schemes, such as the construction industry, certain categories of business consultancy and professional services (lawyers, tax accountants, company formation agents, etc.) and the sale of computer equipment, mobile phones and technology.

Lower-risk sectors would be those which are not immediately and obviously attractive, or known in the past to have been associated with money laundering activity. As with country risk, consultancies will sell advisory services on business sector risk assessment for AML/CFT purposes. There is also publicly-available information on business sector risk. In terms of how you go about creating the business sector risk list, there is no point in re-inventing the wheel. The best place to start is with the business type lists which your institution already has in place for credit assessments and other forms of business risk and opportunity analysis. An example is shown in Table 4.4.

Source of wealth information checklist tool

There will be occasions when, typically as part of enhanced due diligence (EDD) enquiries, business unit staff will be required to seek information to prove a customer’s source of wealth. Although at first sight this may seem to be a fairly straightforward task of asking and obtaining information from the customer, experience suggests that, in practice, staff – particularly in sales and relationship functions – need to be pushed to do it properly. They often feel that they are putting the overall relationship (and the revenue which comes with it) at risk by asking questions which may be deemed by the customer to be too intrusive. This is particularly so when dealing with the types of wealthy and high-profile clients who are precisely the kind of people from whom such information should be obtained (lest it should turn out that the significant sums which have been entering and leaving their accounts on a regular basis have come from illegitimate rather than legitimate sources). For this reason, such reluctance by staff must be overcome and a good practical way in which to do this is to provide firm and detailed guidance on the questions which they should be asking, as well as more skills-based guidance and training on how to solicit relevant information during the course of normal social interaction. There is more on this in Chapter 5, which deals with reputational risk.

| HIGH RISK (sample) |

| Antique dealers |

| Art dealers |

| Auction houses |

| Computer and computer software/peripheral stores |

| Foreign exchange brokers and dealers (money service bureau – MSBs) |

| Gambling/gaming related services |

| General importers and exporters |

| Manufacturing of weapons and ammunition |

| Motor vehicle dealers (new and used) (retail) |

| Other credit granting |

| Other monetary intermediaries |

| Other recreational activities |

| Precious metals dealers |

| Real estate development – commercial |

| Real estate development – industrial |

| Real estate development – retail |

| Real estate development – residential |

| Real estate development – others |

| Religious organisations |

| Restaurants and bars |

| Retail sale via stalls/markets |

| Retail wine/alcohol stores |

| Sale of used automobile and other motor vehicles (wholesale) |

| Wholesale wine/alcohol |

| Wholesale and retail of gems and jewellery |

| MEDIUM RISK (sample) |

| General/special trade construction of buildings and civil engineering works |

| Construction – residential |

| Construction – industrial buildings |

| Construction – commercial buildings |

| Construction – retail buildings |

| Construction – others |

| Business consultancy |

| Highway, street, bridge and tunnel construction |

| Water, sewers, gas, pipeline construction |

| Construction of dams and water projects |

| Communication and power lines construction |

| Construction of railways |

| Other heavy construction |

| Other building completion works |

| Other building installation activities |

| Retail sale of pharmaceutical and medical products |

| Renting of construction or demolition equipment with operator |

| Sale of motor vehicle parts and accessories (retail) |

| Maintenance and repair of motor vehicles |

| LOW RISK (sample) |

| Land reclamation works |

| Grain farming |

| Oil palm |

| Oil seeds or oleaginous fruit |

| Tobacco farming |

| Rubber plantation |

| Sugarcane farming |

| Cotton farming |

| Manufacture and/or distribution of industrial products |

| Vegetables, horticultural and nursery products |

| Cocoa plantation |

| Coffee plantation |

| Tea plantation |

| Other fruits, nuts, beverage and spice crops necessary |

| Livestock farming |

| Other animal farming, production of animal products |

| Agricultural and animal husbandry service activities |

| IT consulting |

An example of a source of wealth checklist is shown in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5 An example source of wealth checklist

CDD documentation tools

The requirement in the FATF standards is that financial institutions should undertake customer due diligence measures against their customers when establishing business relations and when carrying out occasional transactions which fall within certain parameters. This immediately raises a practical issue. There is a large array of different types of customers of varying legal compositions. It’s possible that your company might have to conduct CDD against any of the following:

- individuals

- smaller companies in the private sector

- more well-established, substantial private sector companies

- publicly listed companies

- governments

- state-owned corporations

- regulated financial institutions and correspondent banks (dealt with in the next section)

- partnerships

- trusts and foundations

- non-government organisations

- charities

- clubs, societies and unincorporated associations

- entities conducting one-off transactions above certain financial thresholds

- if you are a large international group, introductions from other business units in other countries.

Your procedures will need to be very clear in terms of what information and documentation is required in relation to each in different circumstances, and the verification methods used. For these purposes you will require a detailed set of tools which show staff what types of documents must be obtained from customers and about different types of customers during the CDD process, for each of the different due diligence risk classification levels (SDD, NDD and EDD).

All such tools are not reproduced in detail here, but would basically comprise the legally required identification and verification documents for each of the above categories of customer.

The following example shows a CDD documentation tool for corporate customers, showing the different documentation requirements depending on whether the customer is classified as SDD, NDD or EDD.

Example: CDD documentary requirements for corporates

Simplified Due Diligence (SDD)

Identity and due diligence information:

- Company number

- Registered office in country of incorporation

- Business address

- Purpose and reason for opening the account or establishing the relationship (unless obvious from the product)

- The expected type and level of activity to be undertaken in the relationship (e.g. total account turnover, largest expected balance (CR/DR)).

Verification:

- Evidence of listing of publicly quoted companies (e.g. copy of relevant internet page published by the regulated market). Evidence of existence of government entity (e.g. copy of web page from government website).

- The majority ownership status of any subsidiary.

- The licensing and regulatory regime status of the company (e.g. letter from regulator confirming that the company is regulated).

- Authority of authorised signatory(s) to open and operate the account (e.g. board resolution/mandate or government authorising document).

Normal Due Diligence (NDD)

Identity and due diligence information:

- Full name

- Company number or other unique identifying number assigned by government to the entity (e.g. taxpayer identification number)

- Registered office in country of incorporation

- Business address

- Purpose and reason for opening the account or establishing relationship (unless obvious from the product)

- The expected type and level of activity to be undertaken in the relationship (e.g. total account turnover, largest expected balance (CR/DR))

- Names of all directors, partners, proprietors

- Names of all beneficial owners

- Names of shareholders owning at least 25 per cent of the shares or voting rights

- Names of all authorised signatories

- Nature and details of the business

- Whether the customer conducts business with any countries subject to national or international sanctions

- Source of funds

- Copies of recent financial statements.

Verification:

- Identity of business (e.g. relevant company registry search, or certified copy of certificate of incorporation/partnership deed/business registration certificate (or equivalent) or other equivalent independent and reliable sources. The guiding principle is that the documents used have been issued by a government, government body or agency or accredited/regulated industry body. For corporate documents, certification can be by an appropriate authority of the customer (e.g. the company secretary).

- Identity of one controlling director (e.g. managing director), partner or proprietor (see ‘Officers of corporations’, below).

- Identities of all significant beneficial owners owning at least 25 per cent of the shares or voting rights.

- Authority of authorised signatory(s) to open and operate the account (e.g. board resolution/mandate).

- Where the shareholders are not natural persons, the structure should be investigated until the natural persons or a publicly listed company are identified. It should then be established whether any such natural person(s) hold a proportionate interest of 25 per cent or more of the customer or exercise management control over it (i.e. significant beneficial owners).

- Companies with an unduly complex structure of ownership should be subjected to EDD. This generally means there are three layers or more layers of shareholding ownership between the company and the ultimate principal beneficial owners.

For company officers

Identity and due diligence information:

- Full name

- Current residential address

- Date of birth

- Nationality

- Identity document number

- Nature and details of the business/occupation/employment.

The preferred document to verify identity would be a government issued document which contains the name, an evidencing photograph or similar safeguard and either the residential address or date of birth. For example:

- passport

- driving licence

- national identity card or

- Electoral ID card.

Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD)

As for NDD, except

- Verify the identities of two controlling directors (or equivalent) that must include the managing director or CEO.

- In addition, fuller investigations into the nature of the entity’s business, and the legitimacy of its business activities and revenues/sources of wealth and funding. (Corroboration of source of wealth could be from actual documents provided by the customer (e.g. the proof of a sale of a property), available public information surrounding the individual or, where appropriate, from a detailed due diligence report of the relationship manager that has included elements of external enquiry and detailed meetings with the customer.)

These tools are really nothing more than a more detailed, granular manifestation of the ‘digging holes’ graphic shown in Figure 4.4. If you look at it, you’ll see that for SDD there is a relatively light amount of information and verification required, but that these requirements increase as the risk classification rises up through NDD and into EDD. Similarly, detailed tools should exist for each of the customer categories outlined above.

EXAMPLE RISK ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORKS

Constructing a CDD framework for corporate/wholesale banking business

Given the complexity of many modern financial transactions and structures, it may not be immediately clear to your staff who the corporate customer actually is, and so this is something which will need to be spelled out in your policy documents and your training.

Who is the customer? In the type of relationship depicted in Figure 4.6, the answer is straightforward. The customer is a company called XCo that is placing deposits with and taking loans from the bank. However, things may not always be so obvious, so here are a few examples of different types of financial transactions which could be included in policy documentation to guide staff on ‘Who is my customer?’

Figure 4.6 ‘Plain vanilla’ banking relationship

Examples

Case 1

AlnaBank buys from K Bank the loan portfolio of WonderTaste Limited, which is in financial difficulties and requires a debt restructuring which K Bank is not prepared to provide. According to the workout deal, in addition to acquiring the existing loans, AlnaBank is also to provide an additional credit line of $20 million.

KBank and WonderTaste are both clearly candidates for CDD. But which of these should the CDD be conducted against, or is it both?

The answer in this case is that CDD must be conducted against both counterparties, KBank and WonderTaste. AlnaBank is receiving and paying for financial assets from KBank, and WonderTaste will actually be opening accounts and (hopefully) repaying loans.

Case 2

The hi-tech fund of AlnaBank Growth Ventures Limited (AGVL), AlnaBank’s private equity arm, receives funds from X Limited, Y Limited and Z Limited and invests them in Advance Software Limited, so as to acquire a 65 per cent stake.

The candidates for CDD then are, respectively, X Limited, Y Limited, Z Limited and Advance Software Limited. But against which one should AlnaBank conduct CDD?

The answer in this case is that CDD must be conducted against X Limited, Y Limited and Z Limited since they are the entities from whom funds are being received as part of the investment process. Normally there would be no requirement to conduct due diligence against investee companies such as Advance Software Limited, nevertheless AGVL would be wise to undertake integrity checks against Advance Software before making the investment (see Chapter 5 on managing reputational risk).

Case 3

Joyful Bank, Beijing branch, sets up SWIFT and tested telex arrangements with AlnaBank in India, which are also to be utilised by Joyful Bank’s New York and London branches. Joyful Bank is incorporated in the People’s Republic of China.

The possibilities for CDD here, therefore, are the three different branches of Joyful Bank in Beijing, New York and London. Against which must AlnaBank conduct CDD?

The answer here (in the absence of more stringent local requirements or separate subsidiary status for each branch AlnaBank would need to check) is that Joyful Bank would constitute a single legal entity, and as such CDD need only be conducted against that entity, i.e. there would be no requirement to conduct individual due diligence against each of the overseas branches.

Case 4

AlnaBank sells corporate bonds issued by Timeless Textiles to Excel Investments Limited, an investment firm. AlnaBank purchased the bonds in the secondary market from Alpha Investments Co Limited.

AlnaBank could conduct CDD against Timeless Textiles, Excel Investments or Alpha Investments. So against whom is CDD required?

The answer in this case is that CDD must be conducted by AlnaBank against both Excel Investments and Alpha Investments, as the subsequent purchaser and initial seller, respectively, of the bonds in question. This is because there is a direct business relationship between AlnaBank and these two entities involving the receipt of funds (from Excel Investments) and assets with value (from Alpha Investments). There is no requirement for AlnaBank to conduct CDD against the initial issuer, Timeless Textiles, because there is no business relationship between the two.

Case 5

The Habibian Brandy Company in Yerevan, Armenia, is exporting brandy to Party Pubs Limited in Thailand. AlnaBank is advising a letter of credit issued by Thailand Bank on behalf of Party Pubs Limited.

CDD would be possible against The Habibian Brandy Company, against Thailand Bank and against Party Pubs Limited. Against whom should AlnaBank conduct its CDD?

The answer in this case is Thailand Bank, since according to the structure of such transactions, Thailand Bank will have instructed AlnaBank, which will be receiving funds from it. There is no customer or other business relationship between AlnaBank and either the Habibian Brandy Company or Party Pubs Limited which, although lying at the commercial heart of the transaction, are not customers of AlnaBank.

Case 6

AlnaBank is the receiving bank on a rights issue being arranged by another bank on behalf of its client, Alpha Limited. In the opening stages of the issue, the following applications are received:

| Applicant name | Amount ($) |

| X Limited | 300,000 |

| Y Limited | 70,000 |

| Mrs Z | 9,000 |

CDD would be possible against all three of the above, but against whom should AlnaBank conduct it? The answer in this case would be X Limited and Y Limited, but not Mrs Z. Why? Because these are one-off transactions and if the issue were oversubscribed, AlnaBank would have to return X Limited’s and Y Limited’s subscription funds which in each case would be above AlnaBank’s maximum threshold for conducting one-off transactions without undertaking customer due diligence (set under the FATF standards at $15,000). This, of course, would be an ideal form of money laundering.

CDD is not required in this case against Mrs Z, however, since the funds which would have to be returned to her in the event of an over-subscription would be below the relevant threshold.

In this case, no CDD would be required against Alpha Limited either, since according to the structure of such transactions, AlnaBank would have no direct business relationship with Alpha Limited as the issuer.

Note: had X Limited’s and Y Limited’s funds come from accounts which they held at regulated financial institutions in countries which AlnaBank deemed to have a good, strong AML regulatory framework, then it would be entitled in its policies to rely on the CDD conducted by those financial institutions (as permitted under Recommendation 17 of the FATF standards). However, AlnaBank would have to satisfy itself that copies of relevant documentation would be available immediately upon request. It should also bear in mind that, notwithstanding its operation of such ‘reliance’ provisions, it would still remain legally responsible for any negative outcome.

Case 7

AlnaBank is the lead manager in the syndication of a loan to Vessyan Textiles, a listed company. The other syndicate banks are Blue Bank, Green Bank and Yellow Bank.

CDD is possible against Vessyan Textiles and the syndicate banks, so against whom should it be conducted?

The correct answer is Vessyan Textiles, which is actually entering into a transactional relationship with AlnaBank. No CDD is required against the syndicate banks since, according to the structure of a syndicated transaction, they do not enter into a transactional relationship with AlnaBank.

Risk-classifying corporate clients: example methodology

Having decided against whom we need to carry out due diligence, before we can determine what level of information and verification is required, we need a practical methodology for classifying clients as either SDD, NDD or EDD. Such a system:

- should be policy-based, such that decisions made about individual relationships can be referred back to a policy document

- should be capable of being operated by the business units themselves, only requiring separate input from your AML specialists in circumstances required under the policy or in difficult or borderline cases where staff are unclear, and

- must be reasonably robust and flexible, in the sense that it covers multiple different scenarios and is responsive to business needs (whilst, of course, meeting the compliance standards which have been determined).

Corporate banking risk calculator tool

Applying the above, therefore, you need to have a methodology for calculating the appropriate CDD risk level in a relationship which is based on the principles which we have been discussing, and which utilises the country and business sector risk tools described earlier – see Table 4.6.

What the calculator does for business units, therefore, is to provide a systematised, process-driven way to arrive at a reasoned risk-assessment, all else being equal. This last caveat is important because other policy factors will need to be taken into consideration in arriving at the classification. These are dealt with below. It is also important to remember that such processes must be subject to human overview and the application of commonsense.

EDD factors checklist

The following example framework is robust, albeit quite simple (it is possible to construct more complex and sensitive frameworks). Under this framework, relationships are classified for business reasons in the lowest level possible for the perceived business risks which they present. The presence of one or more factors determines that some relationships must always be classified as EDD. These are:

- PEPs, or customers linked to PEPs (unless the PEP is a non-executive director from a low-risk jurisdiction and does not own or control 15 per cent or more of the customer)

- entities involved in gambling/casinos

- entities involved in the arms trade

- entities dealing with diamonds and other precious stones

- offshore trusts

- entities with complex ownership structures (e.g. three or more layers of ownership)

- entities that issue bearer shares (that is, shares of which ownership passes through physical possession of share certificates).

In other words, where any single one of the above features is present in the relationship, that relationship must be classified as EDD, notwithstanding the presence of multiple, other, low-risk indicators.

SDD factors checklist

Relationships which can be classified as SDD (unless any of the compulsory EDD features are present, or there is too great a preponderance of other high-risk features) are relationships with corporate entities that are:

- publicly quoted companies or their subsidiaries listed on a well regulated stock exchange

- companies subject to statutory licensing and industry regulation from low- or medium-risk jurisdictions

- government-owned and controlled bodies from low- or medium-risk jurisdictions.

Again, the presence of one or more of the compulsory EDD features in any of the above relationships would mandate an EDD classification.

In all other cases, according to this framework, you would use the corporate banking risk calculator, the country risk list and business sector risk tools described earlier, in order to arrive at the appropriate risk classification for customers. You would then use the relevant CDD documentation tool to designate in each case what the specific information and verification requirements were for each customer.

Matching information and verification intensity/depth to risk classification

As we saw earlier, the information-seeking and verification activity which you undertake on a relationship should become deeper and more intense as the perceived level of risk rises. The greater the risk, the deeper you need to dig.

We also looked at a range of different types of information relating both to natural persons in corporate roles (directors and officers of legal entities) and to the entities themselves, and the various methods by which such information could be verified.

The CDD documentation tool can be used in order to assign reasonable and appropriate information and verification requirements to the different risk classification categories (SDD, NDD and EDD) for corporate/wholesale banking customers.

Taking all of the above into account, you should now be able to assign a risk classification to different relationships and allocate appropriate CDD requirements to them. So here are some example cases on which to try out your CDD skills.

Case 1 – Ace Construction Limited

Ace Construction Limited is registered in your country and doing business there, specialising in so-called ‘intelligent’ buildings. Through a recently-won large new contract, it is also doing business in Nigeria. The company was founded six months ago by directors and shareholders (who are also the beneficial owners) David Harman and Peter Markin on the back of two initial, specialist, small office construction contracts undertaken for a Nigerian company which wants to use the technology in their new head office building. Herman Taylor, a local lawyer, holds a power of attorney and is also an authorised signatory.

What risk classification would be appropriate for this relationship and what CDD information and verification should be obtained?

The answer in this case is that this is an EDD classified relationship. From the facts, we can determine immediately that it cannot be an SDD account because it does not fulfil any of the criteria for SDD status that we outlined earlier (it isn’t publicly-quoted, it isn’t subject to statutory licensing and it isn’t government-owned or controlled). We also know that it doesn’t have to be EDD, because none of the features triggering mandatory EDD status are present (there are no PEP connections, the company is not involved in the gambling, armaments or diamond/precious metals trade, it is not an offshore trust, it doesn’t issue bearer shares and it doesn’t have a complex ownership structure, as defined). Since it cannot be SDD and need not be EDD, therefore, it could be either NDD or EDD and to determine this we refer to the corporate banking risk calculator. The relevant criteria for using this calculator are country risk (Nigeria = high: remember that the country risk will be the higher of the place of incorporation and place of business, if different), business sector risk (construction = medium) and business age (less than one year = high), according to which the overall classification using the calculator comes out at EDD, as shown in Figure 4.7.

In terms of the information and verification requirements, if we look at the CDD documentation tool we can see that the CDD requirements for this business in the EDD section would therefore be as follows.

Company information

- Full name

- Company number or taxpayer identification number

- Registered office

- Business address (if different)

- Purpose and reason for establishing the relationship

- Expected account activity

- Names of all directors and beneficial owners owning or controlling 15 per cent or more of shares or voting rights

- Names of all authorised signatories

- Nature and details of the business

- Whether the company conducts business with sanctioned countries (Nigeria is not one, in 2011)

- Source of funds

- Copies of recent financial statements.

Verification of company information

- Certified copy of certificate of incorporation

- Certified copy of search at Companies Registry revealing identities of shareholders and directors

- Detailed investigation into the nature of Ace Construction Limited’s business, the types and identities of contracts under which it has earned revenue (and the legitimacy of those contracts), i.e. source of wealth checks, corroborated by information from sources outside of, and independent from, the company.

Personal information

For each of the directors/shareholders David Harman and Peter Markin, and also for the power of attorney holder Herman Taylor, the following:

- full name

- current residential address

- date of birth

- nationality

- identity document number (passport, tax identification number)

- details of any other occupation or employment.

Verification of personal information

For each of the above individuals, sight of an original passport, driving licence or national identity card, with copies certified and retained on the file.

Case 2 – The Golden Export Company

The Golden Export Company is incorporated and registered in your low-risk country. Founded in 1989, it distributes a variety of general industrial products all over the region to low- or medium-risk countries. Its turnover last year was $10 million equivalent and it has a capital and asset base of approximately $25 million equivalent. The company provides generous funding for sports facilities in deprived local areas and desk research shows it to be well-established with a good reputation.

What risk classification would be appropriate for this relationship and what CDD information and verification should be obtained?

The answer in this case is NDD. None of the requirements triggering mandatory EDD status are present, so whilst it could be classified as EDD, it does not have to be. None of the factors permitting SDD status are present, so it cannot be SDD. If you look at the calculator, you can see immediately that the country risk is medium, the business type risk is low and the business age risk is low which, if you track it through, comes out at NDD (see Figure 4.8).

In terms of information and verification, again if you look at the requirements in the CDD documentation tool you can see that they are basically the same as for EDD, with the important exception that it is not necessary in this case to undertake the extensive fuller investigations into the nature of Golden Export’s business and the legitimacy of its sources of wealth. It is also necessary to verify the identity of only one of its directors. (Indeed, for a company of this type – a well-established business with a good reputation and a sizeable balance sheet – some financial institutions might not require identity verification of any directors or officers at all.)

Case 3 – Aeglis Consulting Limited