Reputational Risk

When banks go wrong: cases of punishment and penalties

Managing reputational risk: the experience of the MDBs

The integrity ‘red flags’ checklist and the due diligence investigation tools

Where you see the WWW icon in this chapter, this indicates a preview link to the author’s website and to a training film which is relevant to the AML CFT issue being discussed.

Go to www.antimoneylaunderingvideos.com

MANAGING REPUTATIONAL RISK

As we noted at the beginning of the book, money laundering and terrorist financing risks to organisations aren’t just confined to the possibility that your organisation is actually used by criminals and terrorists to launder money and finance terrorist acts. There is a significant risk to the reputation of your organisation if you are found to have fallen short of the standards which are required of you, and this takes the form of financial penalties, public censure by regulatory authorities and of course negative media coverage.

The UK’s Financial Services Authority defines reputational risk as:

‘the risk that the firm may be exposed to negative publicity about its business practices or internal controls, which could have an impact on the liquidity or capital of the firm or cause a change in its credit rating.’

The US Federal Reserve defines it thus:

‘reputational risk is the potential loss that negative publicity regarding an institution’s business practices, whether true or not, will cause a decline in the customer base, costly litigation or revenue reductions (financial loss).’

Clearly, then, reputational risk involves a potentially uncomfortable meeting point between what you do as an organisation on the one hand, and how people judge what you have done on the other. The way you run your business, the actions you take, the risks you assume, the policies you implement (or don’t implement, as the case may be), and the values which you espouse (or say you espouse) must pass the test of third party opinion, be it shareholders, customers, governments and regulators, politicians, NGOs and pressure groups, your fellow industry players and counterparties, the media, members of the public and – let’s not forget this – anyone in possession of a blog, a Facebook page or a Twitter account. In a world of globalised markets, volatile share prices and instant communication, what people think about you and what they are saying about you matters as much as almost anything else you can think of. And when it comes to your dealings with (suspected) criminals, money launderers, terrorists and proliferators of weapons of mass destruction, it’s not hard to see how the sensitivities can become extreme.

One of the things the organisation you work for is almost certainly trying to do is to demonstrate to the world that it is an organisation of integrity, that it is an organisation which they can trust. Failing regulatory tests and engaging in associations with those of a dark reputation are not ways to achieve such an objective.

It’s crucial to note here an important distinction, however, which can sometimes be lost in the scramble to reduce reputational risk. Integrity and reputation are not the same thing. With professional management of an issue, it’s possible to have an excellent reputation whilst actually being an organisation or a person of very little integrity. This is significant in two respects. First, if your organisation is caught out managing its reputation in this way – enjoying the financial benefits of selective lapses whilst milking its overall compliance for all it is worth – then the consequences are likely to be much worse. Secondly, and equally importantly, it must be remembered that customers, too, are aware of the benefits of reputation management and will often employ sophisticated techniques to bamboozle relationship managers and risk functions into thinking that they are a certain type of person when in fact they are the very opposite.

Ideally, therefore, in order to manage reputational risk effectively your organisation requires not only effective policies and controls combined with a genuine determination to apply them at all times (even when there are negative financial consequences to doing so), but also the capability to detect reputation management in applicants for business, and to respond appropriately through effective due diligence.

WHEN BANKS GO WRONG: CASES OF PUNISHMENTS AND PENALTIES

To demonstrate the wide range of areas in which financial institutions have been criticised and sanctioned for failing to meet recognised AML standards, below are brief examples of some major instances in recent years.

Example: Bank of Ireland (BOI)

These events at the Bank of Ireland in the UK occurred between 1998 and 2002, by which time there was already a heavy emphasis on AML standards in OECD countries. The regulatory requirements enforced in the UK at the time required that banks should operate ‘such procedures of internal control and communication as may be appropriate for the purposes of forestalling and preventing money laundering’, and that they should adopt ‘reasonable care in countering financial crime’. They also stressed that special care was necessary for high-risk products and cash, and that a complete audit trail of beneficial ownership was essential. During the period in question the BOI operated a ‘drafts outstanding account’ in which a customer was allowed to deposit cash in exchange for BOI bank drafts (instruments drawn on the bank itself without reference to any underlining customer account), made payable to the BOI itself, which could then be deposited at other BOI branches in exchange for cash.

In fining BOI £375,000, the regulator, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) noted that by issuing drafts to itself, BOI broke its own internal controls in relation to the issuing of drafts and that the use of drafts was outside the customers’ normal business activity. The FSA also noted that cash did not actually pass through the customers’ accounts and was not, therefore, auditable. It found that staff understanding was incomplete and untested and extended only as far as the account opening process and the need for identification. For four years neither line management, peer review, nor audit identified the suspicious transactions despite ‘cash for drafts’ being identified as a potentially suspicious transaction type since 1994, in the bank’s own policy manual.

Source: Information drawn from http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/final/boi_3laug04.pdf

Example: Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS); Bank of Scotland (BOS)

These events occurred one after the other in 2002 and 2004 and both related to failings by the institutions concerned to retain proper records, particularly identification records.

In both cases the key regulatory requirement was that banks ‘must take reasonable steps to find out who their clients are by obtaining sufficient evidence of the identity of any client’ and ‘to retain copies of identity evidence and records of where that evidence is kept’. Record-keeping standards also required maintaining account opening records for five years following the closure of the account and transaction records for five years following the transaction. In the case of RBS, the regulator’s (FSA) inspection revealed that in 89 of 181 accounts sampled, there were insufficient identity documents, including a failure to retain copies of any details at all on some files. In the case of BOS, the FSA found a failure rate of 55 per cent across sampled accounts, with a particular concern being on the bank’s apparent inability to identify at which point of the document process the deficiencies had occurred.

It is notable that both banks reported the deficiencies to the regulator having discovered them themselves, yet this was not sufficient to escape censure and punishment. It is also worth noting that the costs of remediation in both banks, amounting to millions of pounds, have vastly outweighed the predicted costs of implementing and enforcing proper procedures in the first place.

Source: Information drawn from http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/final/rbs_12dec02.pdf and http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/final/bos_12jan04.pdf

Example: Raiffeisen Bank

Raiffeisen Bank’s (RZB) London branch operated in a regulatory environment which required that banks ‘must set up and operate arrangements including the appointment of a Compliance Officer, to ensure that it is able to comply and does comply with the rules’. Those rules were wide ranging, covering the areas described already, and others. The regulator (FSA) visited RZB’s London branch in September 2002 and discovered that the bank’s anti-money laundering procedures had not been updated since June 1999. This was despite the fact that there had been major regulatory changes in the interim period, particularly dealing with recommended identification procedures. The regulator warned the bank that an inspection would take place later in that year, and that particular areas of concern were higher-risk areas such as agents, overseas corporations and trusts, non-European Union financial institutions and customers from Non-cooperative Countries and Territories (NCCT), third-party payments and non-face-to-face customers. In terms of identification records there was a failure rate of more than 50 per cent on sampled accounts. The inspections revealed the problems which RZB had had in retaining an effective Compliance Officer. A Compliance Officer had resigned in October 2001; a new one had resigned in July of 2002 and a third one, appointed in August 2002, had then not revised the bank’s procedures in time for the inspection.

Source: http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/final/r20_5april04.pdf

Example: Abbey National

Now part of the Banco Santander Group, Abbey National was one of Britain’s largest mortgage lenders. The regulations in force required banks to take reasonable steps ‘to ensure that any internal report of potentially suspicious activity was considered by the Compliance Officer’ and, further, that if the Compliance Officer suspected money laundering, then they should report that promptly to the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU). The regulations also require ‘reasonable care in countering financial crime’. Abbey National had introduced a ‘self-certification’ process for Know Your Customer (KYC) measures in November of 2000. This included a capability for branches to self-certify their retention of identification records. In March 2003 an internal audit revealed failure rates on samples of 32 per cent in the identification documentation of new customers. The regulator (FSA) found that Abbey’s failings were indicative of ‘wider systems and controls failings across the group over a prolonged period of time’. Furthermore, there were serious shortcomings in the effectiveness of suspicious activity reporting. Some 58 per cent of reports were sent to the FIU more than 30 days after the internal reports had been filed with the compliance department. Of those, 37.6 per cent were sent up to 90 days after the initial report, and 8.4 per cent were actually sent up to 120 days after the internal report, with a further 12 per cent being sent more than 120 days after the initial internal report had been filed. This example proves the clear importance of having systems and procedures in place which facilitated the speedy processing and reporting of suspicious activity.

Source: http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/final/abbey-nat_9dec03.pdf

Example: ABN AMRO

ABN AMRO fell foul of the US AML regulatory system, which required that banks must have a programme ‘reasonably designed to assure and monitor compliance’. ABN’s North American clearing centre in New York dealt with 30,000 fund transfers a day and had clients that were deemed to be high risk including hundreds of shell banks (a shell bank, it may be recalled, is a ‘virtual’ bank with no physical presence in its country of incorporation and which is not part of a larger banking group). Upon inspection, FINCEN (the US’s Financial Intelligence Unit) found that violations of the Bank Secrecy Act ‘were serious, long standing and systemic’. Only one person was in charge of monitoring this activity. There had been sporadic manual monitoring to start with and when suspicious activity reporting was automated, many reports were produced which, however, were never acted upon. There was inadequate due diligence on bank customers from higher-risk jurisdictions or in connection with higher-risk transactions, despite the fact that there had been numerous regulatory warnings about such customers and transactions. A poor record of suspicious transaction reporting, a non-existent training programme and no proper system of internal controls compounded the problems. ABN was fined $30 million along with other fines.

WWW

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/20/business/worldbusiness/20bank.html and http://www.fincen.gov.news_room/nr/html/20051219.html

Note: a training film dealing with this case and the one below can be previewed at http://www.antimoneylaunderingvideos.com/player/punishments.htm.

Example: Lloyds TSB

In 2009 the UK-based bank, Lloyds TSB, was fined in the US after admitting to falsifying information on hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of international wire transfers – the electronic messages through which payments are made between counterparties in different countries. The wire transfers in question involved companies in countries that were the subject of sanctions by the US government. US investigators were probing links between the Iranian government and two Manhattan-based companies when they stumbled on a trail of Iranian money entering the city via Lloyds. The UK branch of an Iranian bank would send an electronic payment message to Lloyds via the SWIFT system. However, knowing that the suspicion of the US authorities would be alerted if the payment message made reference to Iran or to an Iranian company as the source of the funds, Lloyds staff would then re-key the data in the SWIFT message, leaving out any reference to Iran, before sending it on to the US. This process was known as ‘stripping’. It didn’t come about through the misdemeanours of a few rogue staff. Rather, it happened under standing operating instructions.

The US authorities have electronic filters to detect wire transfers from sanctioned countries, but the lack of identification details meant that the Lloyds transfers could get through, especially since they came from a reputable UK bank. Taken with other transactions involving another sanctioned country, Sudan, when confronted by the US authorities Lloyds admitted to over $350 million of illegal transactions between 2001 and 2004. The transfers in question were made to buy goods and services from US companies and from companies in other countries that wanted payment in dollars. The Manhattan District Attorney’s Office said that they feared that some of the funds ‘may have been used to purchase raw materials for long range missiles’. Lloyds was hit with a fine of $350 million – at the time the biggest penalty ever against a single financial institution for breaches of sanctions legislation. The bank also had to conduct an audit of a wide range of other transactions over the period in question to determine their legitimacy.

Source: http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Documents/lloyds_agreement.pdf

WWW

Note: a training film dealing with this case and the one above can be previewed at http://www.antimoneylaunderingvideos.com/player/punishments.htm.

Citibank Salinas: a seminal case study

Most of the above examples didn’t involve actual proven money laundering but were instead breaches of applicable laws and international standards. The case below did involve actual money laundering. It was one of a series of cases affecting the same institution, Citibank, which put severe pressure on its reputation and arguably contributed to the changes that have taken place in the private banking sector in relation to AML issues since then. It counts as a seminal case and for that reason in 2007. I wrote the detailed article, below, for Lesson’s Learned’s house magazine.

Example: Citibank

With increased scrutiny and with seemingly ever greater due diligence expectations being placed on the world’s banks and investment institutions, now seems like an appropriate time to revisit one of the classic archive cases – Citi-Salinas – and ask yourself some searching questions; namely, ‘What has my institution learned from this?’;‘How can I be sure that our policies are being followed?’; and, always the most sombre, ‘Could it happen to us?’

It is more than 15 years since Raul met Amy and started opening the various Salinas accounts with Citibank in New York, Switzerland and elsewhere.

Below, we recount the facts of the case as revealed by the 1999 US Senate hearings, before turning to the lessons learned.

A PEP comes calling

Raul Salinas was the brother of the former President of Mexico, Carlos Salinas. For five years during the late 1980s he was Director of Planning for Conasupo, a Mexican state run agency regulating certain agricultural markets, with an annual salary of up to $190,000. From 1990 until mid-1992, he was a consultant at a government anti-poverty agency called Sedesol.

In January 1992, Carlos Hank Rohn, a prominent Mexican businessman and long-time client of Citibank’s private bank, telephoned his private banker, Amy Elliott, and asked her to meet with him and Raul Salinas that same day. Elliott was Citi’s most senior private banker in New York handling Mexican clients. At the meeting in New York, which was also attended by an even more senior private banker, Reynaldo Figueiredo, Carlos Hank provided the bankers with a strong personal reference for allowing Salinas to open an account. In May 1992, Elliott flew to Mexico and duly obtained Salinas’ signature on account opening documentation. She proposed accepting him as a client without investigating his employment background, financial background or assets, and waiving all references other than the one provided by Mr Hank. The head of the Western hemisphere division of the private bank, Edward Montero, approved the opening of the account. Such was the secrecy involved that the private bank’s country head in Mexico, Albert Misan, was not consulted and apparently did not even learn of the existence of the account until 1993. In June 1992 Elliott wrote in a monthly business report that the Salinas accounts had ‘potential in the $15 to 20 million range’.

Account set-up

After accepting him as a client the private bank opened multiple accounts for Mr Salinas and his family. The New York office opened five accounts and the private bank’s trust company in Switzerland talked to him about opening additional accounts in the name of a shell corporation (a nameplate company existing as a purely legal entity, not as an operational one). A Confidas employee wrote in June 1992:

‘The client requires a high level of confidentiality in view of his family’s political background ... This relationship will be operated along the lines of Amy’s “other” relationship; i.e., she will only be aware of the “confidential accounts” and will not even be aware of the names of the underlying companies ... Please note for the record that the client is extremely sensitive about the use of his name and does not want it circulated within the bank. In view of this client’s background, I think we will need a detailed reference from Amy, with Rukavina’s [Hubertus Rukavina – the head of the private bank and a Confidas board director] sign-off for our files ...’

The ‘detailed reference’ was never obtained and neither was Rukavina’s sign-off, yet Citibank in the Cayman Islands activated a Cayman Islands shell corporation called Trocca Ltd to serve as the owner of record for private bank accounts benefiting Mr Salinas and his family. Cititrust used three additional shell or ‘nominee’ companies to function as Trocca’s board of directors, Madeline Investments SA, Donat Investments SA and Hitchcock Investments SA, and a further three nominee companies to serve as Trocca’s officers and principal shareholders, Brennan Ltd, Buchanan Ltd and Tyler Ltd. Cititrust controlled all six companies which were routinely used to serve as directors and officers of shell companies owned by private bank clients. Approximately one year later Cititrust also established a trust, identified only by a number (PT-5242), to serve as the owner of Trocca. The result of this elaborate structure was that Mr Salinas’ name did not appear anywhere on Trocca’s incorporation papers. Separate documentation establishing his ownership of Trocca was maintained by Cititrust in the Cayman Islands, under secrecy laws restricting its disclosure. Even Amy Elliott was not aware of the name of the shell corporation and Mr Salinas was not referred to by name, but by the acronym ‘CC-2’, or ‘Confidential Client No. 2 (CC-1 being Carlos Hank Rohn).

After Trocca was established the private bank opened investment accounts in London and Switzerland in the name of Trocca and later, in 1994, a special name account was opened for Mr Salinas and his wife in Switzerland under the name of ‘Bonaparte’.

Movement of funds

After his accounts were first opened, Mr Salinas made an initial deposit of $2 million via the account of Carlos Hank, who told the bank that these were monies provided by Salinas in respect of a business transaction which never proceeded. The funds were divided between the Salinas accounts in New York and the Trocca accounts in London and Switzerland. But it was in May 1993 that the arrangements under which the bulk of the Salinas funds were to be moved were set up. Elliott met with Salinas and his mistress (later to become his fiancée), Paulina Castaňon, at his home in Mexico, where he explained that he wished to move funds out of Mexico to avoid the volatility which traditionally accompanied Mexican elections. In order to provide maximum confidentiality on this undertaking, it was also agreed that Ms Castaňon, using an alias ‘Patricia Rios’ (Rios being her middle name) would deposit cashiers’ cheques with Citibank’s Mexico City branch, from where the funds would be wired through to a Citibank account in New York, for onward transmission to the London and Switzerland accounts. Although senior management in Mexico denied knowledge of the arrangements, Elliott herself cooperated fully, even setting up a meeting between herself, Castaňon/Rios and a service officer at the Mexico City branch to explain the arrangements and ensure that the cheques would be accepted.

Cashiers’ cheques were a form of instrument, similar to a bank draft, which were drawn on the banks themselves and which did not, therefore, reveal the beneficial owner of the funds in question, and the New York account to which the funds were then to be wired (marked for Amy Elliott’s attention) was a ‘concentration account’ – an account which commingled the funds of various clients with other funds belonging to Citibank itself, without revealing who owned what. Given that neither Salinas nor Castaňon/Rios held any accounts with Citibank in Mexico City (which must therefore have received the funds into its own nostro accounts), and given that the Salinas accounts in London and Switzerland were trust company or code name accounts, these arrangements had the effect of disguising completely the beneficial ownership of whatever volume of funds would eventually pass through them (see p. 173).

These funds turned out to be substantial, and in any event way above the initial ‘$15–20 million range’, referred to by Elliott in her June 1992 business report. The sums involved were very large and were deposited within very short periods. For example, in May and June 1993, in a period of less than three weeks, seven cashiers’ cheques were presented to the Mexico City branch totalling $40 million, and over a two-week period in January 1994 four cashiers’ cheques totalling $19 million were deposited. By the end of June 1994 the total funds in the Salinas accounts originating from Mexican cashiers’ cheques amounted to $67 million. A further $20 million was transferred using other methods, leading to a grand total in excess of $87 million. In June 1993, Elliott emailed a colleague in Switzerland:

Source: http://www.gao.gov/archive/1999/os99001.pdf

‘This account is turning into an exciting and profitable one for us all. Many thanks for making me look good!’

The Salinas arrests and the private bank’s reaction to them

In early February 1995, the Mexican press started to report that Salinas was under suspicion of murdering his former brother-in-law, Luis Massieu, a leading Mexican politician. Questioned by a presumably concerned Elliott, Salinas claimed that the charges were politically motivated and untrue. Then, on 28 February 1995, he was arrested and imprisoned in Mexico on suspicion of murder. (After a lengthy trial, a conviction followed, which was upheld on appeal in 1999.) Nine months later, on 15 November 1995, Salinas’ wife was arrested in Switzerland and the following day the Swiss authorities froze more than $130 million sitting in Salinas controlled accounts with various banks – including Citibank. The rumours were that the Swiss authorities were investigating allegations that Salinas had been involved in laundering the proceeds of illegal narcotics and, sure enough, three years later in October 1998, proceedings in Switzerland were commenced on that basis.

The private bank’s reactions to this reputational disaster unfolding before it have since become well documented, as has Amy Elliott’s role as the classic relationship manager ‘caught in the middle’ of a corporate environment that claimed that anti-money laundering (AML) and client due diligence (CDD) policies were important, but which also, at that time, apparently did not enforce them consistently enough. They are revealed in detail within the pages of the report on the hearings of the Senate Committee on Investigations on private banking and money laundering in November 1999, and show the following.

- Initial reactions: in March 1995, soon after Salinas had been arrested for murder, tape transcripts of conversations between the bank’s New York, London and Swiss offices reveal that the initial instincts of the bankers, far from making life more easy for the law enforcement investigations which were bound to follow, were rather to make it in practice more difficult for them. For example, the then head of the private bank, Hubertas Rukavina, mooted sending the funds held in the London accounts over to Switzerland so as to make their discovery more difficult – an option which was considered but rejected, apparently, however, primarily on the grounds that the transfer would be obvious in London’s books. The same transcripts also reveal that the bankers discussed calling in loans which had been made to Trocca against its deposits, so as to ensure that the bank was not out of pocket in the event that the Trocca funds were frozen.

- Absence of due diligence records: it became clear during the hearings that despite the existence of clear policies requiring that information on clients’ backgrounds and sources of wealth be collected within the bank’s CAMS (Client Account Management System), in fact no entries had been made at all regarding Salinas. There had been a complete blank throughout the three-year period of the relationship.

- Backdating of due diligence records: it then became clear that what records there were had only been completed ex post facto by Elliott in early March 1995 following Salinas’ arrest, apparently at the behest of private bank senior management in London who wanted to feel ‘more comfortable’ about the source of wealth on the account, upon which in fact there was very little knowledge. Furthermore, faced in November 1995 with a request for information from the Swiss authorities following the arrest of Salinas’ wife in Switzerland, the bank’s legal department (who by now had operational control of the accounts) had effected further, after-the-event changes to the CAMS entries. They incorporated reference to a belief that Salinas had sold a construction company – something which Elliott had not included in her own initial attempts at completing the CAMS profile back in March 1995. None of the information had been verified to the extent required by bank policy.

- Absence of effective enforcement of due diligence policies: the senate hearings record how: ‘during this same period, 1992 until 1995, top leadership in the Western Hemisphere division had sent numerous strongly worded memoranda urging, and ultimately ordering, its private bankers to complete and update information on their client account profiles’ and how ‘Several internal audits had specifically identified incomplete client profiles as a problem.’

- Yet apparently nothing effective had been done to ensure that these instructions were followed. None of the senior managers who waived additional personal references for Salinas beyond the Hank reference, enquired as to what other background checks were being made on Salinas and Elliott herself clearly believed that senior management – right up to the very top of the organisation – was both aware of and approved of the Salinas accounts, regardless of whether or not due diligence information was available. The account had earned $2 million in fees and interest for the bank and tapes of conversations made on the day after Salinas’ arrest recorded Elliott saying: ‘Everybody was on board on this ... I mean this goes in the very, very top of the corporation, this was known, okay? ... We are little pawns in this whole thing, okay?’

- Restricted reporting to the authorities: the exact reporting obligations of any bank in the situation in which Citibank found itself, in terms of timing and content, will always be a matter of a legal interpretation dependent on a number of factors. But the senate documents make the point that when the bank filed a criminal referral form with US law enforcement officials on 17 November 1995 – the day after the freezing of the Swiss accounts – the report only referred to the New York accounts, which held only $200,000, and not to the London or Swiss accounts which held over $50 million.

- Failure to identify discrepancies between actual and expected account activity: Elliott had stated in her earliest business report that the account had potential in the ‘$15–20 million range’, yet when the funds actually passing through the Salinas accounts topped $87 million – more than four times what was apparently expected – this did not trigger alarm bells or generate any action to validate the source of this apparently unanticipated stream of wealth.

The case concludes

Having started with a bang, the Salinas case concluded more quietly. The US District Attorney’s Office initiated an investigation into whether money laundering charges should be filed against Citibank or any of its employees, but decided against it – presumably because there was no evidence that anyone in Citibank had suspected wrongdoing and therefore participated willingly in any scheme. It is always difficult being judged by new standards and it is possible to argue that, as the banking industry emerged from the world of ‘anything goes’ into the new era of regulation and public scrutiny, that this was the position which Citibank effectively found itself in. Its Chief Executive, John Reed, who apart from his appearance before the Senate Committee was also forced to endure the indignity of a day in the company of the Justice Department being interviewed about the affair, wrote to the Citibank board:

‘Much of our practice that used to make good sense is now a liability. We live in a world where we have to worry about “how someone made his/her money”, which did not used to be an issue. Much that we had done to keep private banking private becomes “wrong” in the current environment ...’

Amy Elliott, too, in some ways found herself betwixt two worlds, and paid a very public price for it. After describing the positive perceptions of the Salinas family which she had built up over the years, and the habits of Latin American elites in moving sometimes vast sums overseas in order to escape market volatility caused by political turmoil, she stated in her written testimony before the Committee:

‘It is easy to ignore the context I have described and instead to focus on isolated details in this matter and make them seem questionable. The world in which I operated as a relationship manager in the early 1990s was different from the private banking environment today. Procedures, technologies and safeguards are very different today at Citibank ... I only ask you, with all due respect, to keep in mind the broader picture I have described as you frame your enquiry to me.’

Lessons learned

The world was surely different back then, and if you’re a financial crime professional, re-reading the case makes you realise just how far things have come since the early to mid-nineties; Wolfsberg, the Patriot Act, EU III, the risk-based approach have all come into being. And yet despite the passage of time, some of the issues this case raises are timeless.

- If you have a state-of-the-art compliance policy, what good is it if it isn’t followed at the ‘coal face’?

- If mixed messages are being sent out with firm AML policies on the one hand but a failure to deal with non-compliance on the other, where does that leave the relationship managers – the ‘poor bloody infantry’ who have to deliver both compliance and revenue?

- If the corporate culture is perceived by staff as prizing revenue above all else, then where does that leave the organisation as a whole in terms of its reputational exposure when things go wrong?

Shortfalls identified included:

- no proper identification of the customer

- no effective KYC on the customer relationship

- adequate documentary links between client identity and ownership of assets were not maintained

- information on sources of wealth were not obtained

- the substantial discrepancy between expected versus actual funds volume was not spotted ...

- and as a result, suspicious activity was not reported

- there was a delay in making a suspicious activity report for six months

- account documentation was doctored after the event to make it look as if proper KYC had been done

- staff were not supervised properly to ensure the KYC policy was being implemented

- senior management ignored multiple audit warnings.

Source: Parkman, T. (2007) The Salinas Case ‘AML/CFT and Due Diligence Training for Global Markets’, published in Lesson’s Learned’s house e-magazine.

WWW

Note: the training film Too Good to be True dealing with many of these issues can be previewed at http://www.antimoneylaunderingvideos.com/player/tgtbt.htm.

The Riggs Bank/Augusto Pinochet real case

A second ‘real’ case which retains its relevance today actually saw one of the oldest names in US banking brought low and eventually disappear under the weight of regulatory disapproval and public censure. As the events of the Arab Spring continue to reverberate at the time of writing, the Riggs Bank/Augusto Pinochet case demonstrates just how badly things can go wrong when you miscalculate the effect of a banking relationship with a high-profile and controversial political figure such as a head of state.

Example: Riggs Bank

Riggs Bank was a Washington DC-based prestige bank which had built up its reputation over 150 years. It had served 20 US presidents including Abraham Lincoln and had supplied gold for the Alaska purchase in 1867. A major line of business for Riggs was the operation of accounts for foreign embassies in the US capital. Often this extended into private banking for diplomats, their family members and sometimes other officials from the country in question.

Under the US Bank Secrecy Act, banks at that time, and indeed now, were required to maintain an extensive compliance programme which included requirements that they perform due diligence against their customers, that they identified suspicious transactions involving funds of potentially illegal origin and that they report suspicious transactions to the authorities. Riggs’ own Bank Secrecy Act compliance programme policies and procedures stated that:

‘Riggs Bank will conduct business only with individuals, companies, trusts (beneficial owners) and grantors/power holders of such trusts that we know to be of good reputation and, through proper and thorough due diligence, we know to have accumulated their wealth through legitimate and honorable means.’

Augusto Pinochet Ugarte was a boy from a middle-class Chilean background who rose to become a general in the Chilean army and who seized power from the elected president Salvadore Allende in a bloody coup in 1972. Several years of violent repression followed with some reports putting the number of deaths under Pinochet’s regime as high as 3,200, with tens of thousands imprisoned and tortured. During his rule, until his resignation in 1989, he was also accused of having connections with drug trafficking and illegal arms sales, and of corruptly accruing $28 million. But Pinochet still wasn’t a ‘bad guy’ that everyone could agree on. Millions of Chileans and many in the West supported him because they believed he had saved the country from Communism and directed it firmly and safely to the path of economic growth and prosperity.

It was against this background that in 1994 a senior delegation of Riggs Bank executives visited Chile to solicit General Pinochet’s business. His first personal account with Riggs was opened shortly thereafter, an account which saw balances ranging up to $1.2 million over the next few years. The Riggs Bank approach came despite the fact that General Pinochet was already known internationally as a controversial figure and despite this, in all that followed, no evidence was ever found of any KYC documentation on his account created or maintained by Riggs Bank. Some 18 months after the account was opened, Pinochet was indicted in Spain for crimes against humanity.

Between 1994 and 2002 Riggs opened three more personal accounts for Pinochet, these being a money market account which held balances up to $550,000, a checking account and a ‘NOW’ account, which contained balances of up to $1.1 million. Riggs also established corporate accounts with complex structures for the Chilean ex-president. These included offshore shell corporations (i.e. corporations with no real physical presence, employees or staff) for the receipt of certificates of deposit which benefited General Pinochet and his family. The companies, Ashburton Limited and Althorp Investment Co Limited, all had nominee shareholders (a function which was performed by Riggs Bank (Bahamas) and directors and officers from the accounting firm which was managing the affairs of Riggs Bank in the Bahamas). So Pinochet’s name didn’t appear anywhere on the incorporation papers. At times, these corporate accounts held balances up to $4.5 million.

Much of this activity was occurring despite the fact that in 1998 the Spanish courts had issued international warrants for General Pinochet’s arrest and had issued attachment orders against his accounts throughout the world. In the UK, the Pinochet had been arrested pursuant to the Spanish warrant and was subject to an extradition hearing. Yet no suspicious activity reports were filed by Riggs, which continued to operate the Pinochet accounts without the knowledge of the US authorities. In May 2001, a senior executive at Riggs, Stephen Pfeiffer, forwarded a memo to two senior Riggs Bank officials, containing extensive information on Pinochet’s alleged crimes and the litigation surrounding him.

In the spring of 2002, during a routine examination, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) discovered evidence of the Pinochet accounts at Riggs. Initially the Bank resisted cooperating with the investigation, but in the end it did cooperate and finally, in the summer of 2002, the Pinochet accounts were closed. Federal regulators fined and required various contributions from Riggs Bank to a total sum of $53 million and World-Check has estimated that $130 million was wiped from Riggs’ share value as a result of this and other money laundering scandals. In July 2004 Riggs Bank was sold to the PNC Financial Services Group Inc. and the famous 150 year-old name became extinct.

In its reports on the Pinochet accounts and other accounts where Riggs Bank fell short, the US Senate Permanent Sub-Committee on Investigations stated that ‘Riggs has disregarded its Anti-Money Laundering (AML) obligations, maintained a dysfunctional AML program despite frequent warnings from OCC regulators, and allowed or, at times, actively facilitated suspicious financial activity.’

Lessons learned

How should we assess the significance of the Riggs Bank/Pinochet case and what lessons can be learned from it? Clearly it was very significant because it was one of a number of cases which pointed out the very real reputational risks that exist in doing business with controversial political figures. A key lesson learned from the case is the importance of undertaking a comprehensive risk assessment before a relationship has commenced, which covers not just the sources of wealth and the origin of the funds expected to come into the account, but also the wider reputational issues surrounding allegations against the potential client – both current and historic. If Riggs Bank did do this, then clearly they got it badly wrong. Secondly, it is important that with such individuals, such assessments – and the due diligence which goes with them – should not be a ‘one-off’ event, but should take place on a constant and regular basis, such that new evidence concerning the client is taken into account and processed and so that there can be an ongoing assessment about the suitability of a particular client for a continued business relationship. In this regard, the Riggs Bank/Pinochet case also demonstrates the importance of not allowing relationship managers who may have developed a very close personal relationship with a client, or who may be influenced by their own political views, to override the organisation’s wider sensors regarding the continued suitability of a particular account. Finally, failures in suspicion reporting and in the level of KYC and due diligence on an account will always be punished heavily by regulators, and this case was no exception.

Source: Based on facts from www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate/pdf/109hrg/20278.pdf

MANAGING REPUTATIONAL RISK: THE EXPERIENCE OF THE MDBS

Forging a workable policy for managing reputational risk

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and International Financial Institutions (IFIs) have devoted a lot of attention in recent years to developing their management of reputational risk. They face a difficult task. On the one hand, they are mandated to invest and lend in countries which badly need them, such as less developed economies in the former Communist world, parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America. After all, there is no point in such institutions existing if they are not going to make funds available to help improve people’s lives. On the other hand, the very places where the funds are most needed are, almost by definition, high risk. They often have high levels of corruption and crime. Their institutions are either new and less rooted than their equivalents in the developed world or have actually been compromised by corruption and crime for many years. ‘Integrity’ and ‘transparency’ are viewed by many as luxuries in societies where the real way to get on has been to play fast and loose with whatever rules exist and to get as far as you can as quickly as you can.

How, then, should such institutions deal with applications for financing from, say, a private sector entrepreneur whose business plan seems to offer good returns and great benefits (potentially) to the economic development of the country, but whose past is often shrouded in mystery? This is a crucial question when the past activities of the people concerned may come back and bite the ankles of the institution in a very public way. Just as importantly, regardless of the negative publicity, if they lend to or invest in ‘the wrong person’ then the project itself is unlikely to be successful. Are the MDBs then part of the solution or part of the problem?

Integrity due diligence

Commercial banks may not possess the same social and economic development obligations of the MDBs and IFIs. But particularly since the 2008 financial crisis, the social impact of their operations has never been under such close scrutiny. You can argue about the value or otherwise of allegedly ‘socially useless’ proprietary trading and arbitrage activities, but the provision of financial services to wicked despots and dodgy businessmen and politicians is universally unpopular and today’s banks need some kind of framework within which to analyse a range of integrity-related reputational risks. These risks extend beyond money laundering and terrorist financing into corruption, tax evasion and other forms of criminality, political exposure, corporate governance, regulatory investigations and lawsuits, and the general personal and corporate reputations of the people and companies involved.

The advantages of having such a framework are clear. Whilst each case is unique and must be looked at on its merits, passing each through a common framework of assessment and analysis introduces consistency into what might otherwise be a very subjective process. It forces people to ask difficult questions and provides a common way of both finding the answers and assessing the impact of the answers, all looked at through the prism of the organisation’s reputation: ‘doing the right thing’ and (just as important) being seen to be doing the right thing.

In order to gain some perspective on this, we will look now at the type of framework being followed increasingly by a number of the MDBs/IFIs. What is described here is a generalised version of what are in fact a number of different processes which are specific to each institution. Nevertheless the broad principles tend to be the same.

The process is known as the Integrity Due Diligence (IDD) process. Its key components are:

- an integrity red flags checklist – a list of questions designed to elicit relevant information (see pp. 188–90)

- due diligence research tools – ways of obtaining that information (see p. 190)

- IDD assessment guidelines – policy guidance on interpreting the information and making decisions.

In essence the process is as follows.

The IDD process: initial stage

After the project has been proposed in concept form (usually as a result of a proposal by an applicant), a detailed investigation is undertaken by the banking team responsible for the transaction using the red flags checklist and the due diligence research tools. Documents and other evidence are filed and the outcome of the investigation is subject to an initial, conceptual ‘in principle’ assessment, using the IDD assessment guidelines, to determine whether it passes a ‘funnel test’ of policy principles. This stage of the process is depicted in Figure 5.1.

The four filters shown in Figure 5.1 are drawn from the IDD assessment guidelines and stipulate the circumstances which, all else being equal, will effectively prevent the deal from going any further. They are embodied in the following principles:

1. The transaction cannot proceed if beneficial ownership is unclear

This is a base-level requirement – if you don’t know who the ultimate beneficial owner of a business, structure or asset is, then how can you be sure that it is not owned by a criminal, a terrorist or a political figure? Corporate structures must be investigated back up the chain until all significant beneficial owners have been identified. If this cannot be done then the project cannot proceed, period. Sometimes complex structures will be in place which will make discovering beneficial ownership difficult, particularly in environments where record keeping and the availability of public information may be poor. Sometimes (in fact, quite often) beneficial ownership will not even appear on any written record, but will simply be a matter of fact or, more often, of rumour. Whatever, if the project is worth it (see later) then persistence must be deployed and beneficial ownership established. Sometimes complex structures deployed to disguise beneficial ownership may be an indicator of criminal activity (e.g. tax evasion). But equally, they may simply reflect a business reality in the country in question in which business owners must attempt to disguise the full extent of their wealth in order to avoid demands for payments by corrupt officials. So the presence of a complex structure in itself will not necessarily prevent the transaction from proceeding, but lack of knowledge of beneficial ownership will.

Figure 5.1 IDD process – initial stage

2. No transaction can proceed with parties who have been convicted of, or who are currently under investigation for, serious criminal offences

Serious criminal offences basically mean the predicate offences included in the FATF list of crimes which can give rise to money laundering and constitute, therefore, for example people trafficking and sexual exploitation, racketeering, corruption and bribery, fraud, tax evasion, counterfeiting, murder and kidnapping, robbery and theft, smuggling, extortion, forgery, piracy, insider trading and market manipulation as well as participation in drug trafficking, money laundering, terrorism and terrorist financing offences. In many countries the presence of a conviction or an ongoing investigation is not necessarily indicative of either guilt or a serious case to answer, as the case may be. Likewise, the absence of a conviction or an ongoing investigation is not necessarily indicative of innocence and/or no case to answer. Issues such as the nature of the crime, how long ago it occurred and whether or not it was politically or commercially motivated will be relevant. But, generally, the presence of a conviction or an investigation will prevent the transaction from proceeding.

3. A transaction cannot proceed if a party is currently on a recognised blacklist

This is self-evident and lists checked would include those of the United Nations, the US Department of Treasury and the Office of Foreign Assets Control, the FBI, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Financial Services Authority and those of major central banks and other MDBs/IFIs.

4. The transaction cannot proceed where there is credible evidence of existing links to organised crime and criminal activities

In some instances there will be allegations and rumours that a particular individual or group of individuals are or have been associated with organised crime. Here, the issue of ‘credibility’ is important; the most credible evidence will be that which is corroborated by multiple, independent, impartial sources, as opposed to an allegation made by a single individual who is, say, involved in a commercial or political dispute with the person in question. The criminal activities referred to are the same as those discussed in item 2, above.

Tax affairs are becoming an increasingly important consideration. Involvement of complex structures and Offshore Financial Centres (OFC) may offend tax evasion laws and, as we have seen, tax evasion is now included in the list of predicate offences issued by the FATF. It is also the subject of an increasingly active and determined international effort, orchestrated through the OECD Forum, to reduce it and to punish tax evaders. Therefore, any complex tax structure must be understood so as to ensure that it does not offend against relevant tax laws in the jurisdictions concerned and any OFC involved must be one which has been deemed compliant with the OECD Tax Forum’s international standards on tax information exchange.

If the proposed transaction passes this funnel test, and if it is attractive in other terms (see below) then conceptual clearance is given and more detailed investigations conducted during the secondary stage of the IDD process, depicted in Figure 5.2.

The IDD process: secondary stage

Completion of the red flags checklist at first instance will usually have revealed a number of important issues requiring further investigation. At this stage, assuming all available public sources of information have been accessed using the due diligence resources available (see below), if the transaction is worthwhile in terms of the organisation’s mandate then specialist investigations consultants may be instructed to investigate specific areas of concern revealed in the initial research. Here, the assumption is that they will have access to non-public sources of information, although clearly the use and methods of obtaining such information must remain legal. If such investigations harden any of the evidence of the existence of items 1, 2 and 4 above, then a decision is made to drop the project. More often than not, however, despite the added perspective which such investigations usually give, there are no clear answers and a decision has to be made on the basis of the risks versus the mandate.

Figure 5.2 IDD process – secondary stage

In this regard reference is then made to the following types of interpretation and assessment principles.

5. Relationships with PEPs and other high-risk clients require enhanced due diligence

The involvement of a PEP does not necessarily prevent the transaction from proceeding, but for reasons examined earlier, it creates notable levels of risk which need to be managed. All PEPs are not equal, and generally the involvement in a business transaction of, say, a head of state, president, prime minister or a senior cabinet minister, as well as governors of large regions and mayors of major cities is considered too risky and will prevent the transaction from proceeding.

For those PEPs in lower positions, MDB and IFI organisations will generally refrain from transactions if there is an apparent conflict of interest created by a PEP’s interest in the business transaction on the one hand, and their public duties on the other: for example where a minister of transport owns shares in a bus or train company. Compliance with local law is important, as many public sector service rules will prohibit participation by a public servant in a commercial enterprise.

The types of enhanced due diligence investigations regarding source of wealth described earlier on must be undertaken. If a transaction involving a PEP is to proceed, it must also be subject to enhanced ongoing monitoring (to check that the assessment of risks has not changed in the light of new information). The transaction structure should also be constructed with a view to minimising risks. For example, if permitted by local law, the irrevocable transference of share and ownership rights into the control of an independent third party and documented pre-recusals of the PEP from decisions benefiting or potentially benefiting or being perceived to benefit the financed entity. The same rules apply to close family members and associates of PEPs.

Although the due diligence resources must be used in order to determine whether or not someone is a PEP, generally this is less of a problem than the bigger issue which is establishing whether or not someone may actually be fronting for a PEP. Such situations are common; there is a rumour or an allegation that the disclosed owner of a business structure is not in fact the true beneficial owner, but is fronting for Junior Minister X or Senior Civil Servant Y. In such circumstances, unless the available evidence supports the argument fairly robustly that the rumour is unfounded, then the operation of principle 1 (see p. 182) will generally prevent the transaction from proceeding.

6. Mitigating factors can be taken into account when assessing integrity risks

If a particular transaction is attractive from the perspective of the MDB’s or IFI’s mandate, and if it is not blocked by the operation of principles 1–4, but if there are still concerns about some of the issues which have been discovered during the due diligence process, then mitigating factors can be taken into account when deciding whether or not to proceed. Typical mitigating factors include:

- Time – if a significant period of time has elapsed since the last serious allegation.

- Willingness to change – cynics may scoff, but there is a view (borne out in part by history) that some business people who have pursued illegal activities previously, do reach a point where they intend to leave it behind them and move on to an exclusively legal future, unclouded by their illegal past. (The US ‘robber barons’ of the late nineteenth century are the classic examples often cited.) If there genuinely appears to be little chance of repetition of illegal activities in the future – say because the amount of a person’s reputation and capital invested to date makes the costs too high – then, all else being equal, it becomes possible to take a calculated risk on the individual, subject to the next bullet point.

- Ability to mitigate risks – if the applicant is willing, there is often a series of concrete actions which can be taken to mitigate some of the integrity concerns which may have been raised in the red flags checklist. For example, complex ownership structures can be simplified and made more transparent; international accounting standards can be adopted; independent directors can be appointed to the board of a company; a wide range of warranties and covenants can be included within legal documentation requiring the disclosure of wrongful acts and cooperation with investigations by the lender – all linked to events of default which, in turn, are linked to personal guarantees which place personal rather than corporate wealth at stake; and certain companies, individuals (such as agents) and proposed transactional elements or agents and other individuals can be removed from the deal if they are considered too risky.

If integrity concerns can be mitigated using such methods, then this can result in a move towards a decision in favour of the transaction proceeding.

The remaining four principles are effectively operational ones that concern how the inside process must be undertaken.

7. There must be full disclosure of all risks from as early a stage as possible

8. Transactions must be covenanted and documented in a manner which reflects their risk

See 6 above.

9. Integrity risks must be reviewed throughout the life cycle of a project

Information changes over time and risks need to be reassessed and action needs to be taken accordingly. These requirements form an integral part of the portfolio management process.

10. Where a project is potentially controversial, a clear explanation of the organisation’s rationale for undertaking it should be available

Sometimes, even after the application of sophisticated procedures and thinking, decisions will be made on a hair’s breadth one way or the other. No organisation can be expected to get such decisions ‘right’ 100 per cent of the time. On those occasions when the organisation gets it ‘wrong’ – and when it is accordingly subject to public criticism – it pays to be able to state very clearly what steps the organisation took to try to get it right, and the grounds on which the decision to lend or invest were made.

The reputational decision which has to be made in each case is summed up in Figure 5.3.

In this forcefield analysis, serious integrity concerns, unproven rumours and allegations, the risks of the organisation’s reputation from getting it wrong and the mission risk (objectives not achieved, money not repaid, etc.) are weighed against mitigating factors such as time, recent behaviour, a willingness to undertake reforms, to adopt sound management practices and to accept and embrace mitigation measures.

Each case will be different, but these principles can bring consistency to the analysis. Ultimately, commercial banks operate within their own defined parameters of corporate social responsibility and in order to preserve and enhance their reputations it is against those parameters that they must make their assessments and their judgements.

THE INTEGRITY ‘RED FLAGS’ CHECKLIST AND THE DUE DILIGENCE INVESTIGATION TOOLS

What types of questions should be asked and hopefully answered during the initial stage of the IDD process? What tools and resources can be used to obtain such information?

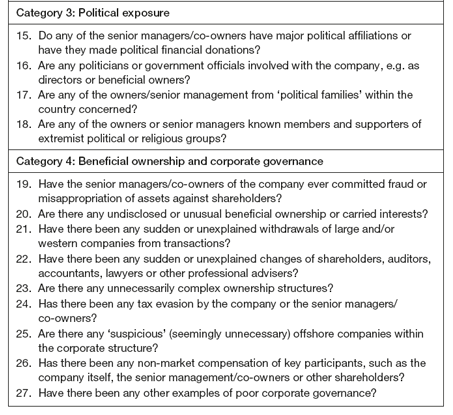

Table 5.1 shows, in checklist format, the areas to be covered and questions to be asked.

Table 5.1 Example ‘red flags’ checklist

The past decade or so has seen a significant increase in the capability of organisations to access, and therefore to analyse, publicly available information through the internet and via various business information products that provide a useful service in information collection and analysis. But traditional methods still count – or should count – for a lot. In all cases, the information needs to be gathered meticulously and either copied and placed on file together with the data research, or recorded as a contemporaneous note. Table 5.2 lists a range of due diligence tools.

Table 5.2 Due diligence tools

PRACTICAL APPLICATION

How might this overall framework apply in a real case? What would the file look like in terms of relevant information and how would the IDD assessment guidelines operate in practice?

We attempt to bring this to life in the form of a fictitious case. First read the project summary to get an initial outline of the proposed project and then access the types of information which you would obtain on such a case were you handling it for real and using the research tools referred to above. Finally, there is an assessment of the project according to the assessment guidelines discussed.

Case: Zubin Deslan and the Belvin Keffl Group

Project summary

- Belvin Keffl (BK) is a former state-owned farming company in the EU candidate country of Moldavia.

- BK diversified after the fall of communism into areas such as food, transport, chemicals, retail and construction.

- It was privatised in 1991 and became owned by the Deslan Group of companies, whose majority shareholder, chairman and chief executive is Zubin Deslan.

- The proposal is for loan financing for the general upgrading and expansion of Belvin Keffl’s truck production facilities in the major cities of Krestinberg and Bantt, which used to produce the old ‘Paka’ state trucks and buses.

- The amount of the proposed investment – €20 million – is to be spent on factory and plant rebuilding using capital equipment purchased from member countries – notably from the Finnish engineering giant, Sarbel Engineering.

- The project has been brokered through the auspices of Peter Valburg, a former Sarbel employee now based in Moldavia and used as an independent consultant throughout the region.

Commercial viability of the project

Commercial viability is good. The market for trucks is likely to remain strong as this robust emerging country continues to grow and the government is a major customer with a constant need for fleet upgrading and renewal. As an oil exporter Moldavia is likely to benefit from high oil prices and this will benefit the economy as a whole. Market research indicates that executives in Moldavian companies are quite patriotic and are prepared to back a national champion if it meets reliability requirements, particularly in the snows of winter, which is where the use of Finnish expertise and matériel will become most useful. Costs are predicted to grow by 6 per cent a year, whilst revenues are estimated to grow by 25 per cent year on year as the business development plan unfolds. There are considered to be potential regional export possibilities, too.

Compliance with environmental policies and strategies

Like many engineering production facilities within the former Eastern Block, BK has suffered from chronic underinvestment, dangerous, outdated facilities, health and safety issues for employees, and high pollution levels, with associated contamination of air, rivers and countryside around the plants. An attractive feature of this project will be bringing the plants up to the latest international standards in these respects.

Moldavian overview

Moldavia has 20 million people, set to grow to 30 million by 2050 with oil and mineral resources. Moldavia is a vast, untapped country which is likely to grow in stature and become a major regional player. It is modernising rapidly and the view is that it is a good country for business, with the current government, formed by the Moldavian National Progress Party (MNPP), apparently committed to the implementation of a full set of market reforms with a view to securing EU membership by 2025. Despite a plethora of government backed initiatives, corruption, however, is still viewed by many foreigners as endemic in everything from the award of business contracts, to the making of regulatory decisions, to the securing of preferment and promotion in both the private and public sectors. Many Moldavians appear to take a relaxed view, nevertheless, at least about ‘soft’ practices such as the giving and receiving of expensive gifts, the payment of small favours to lowly officials in return for expediting bureaucratic processes and the involvement of family members in both business contracts and positions of employment. Practices which they refer to as ‘chaznar traltir’ (literally, ‘greasing the axle’) and which they believe to be globally widespread.

There is a crime problem in Moldavia. It is improving but organised crime undoubtedly exists and the use of intimidation, violence and even murder to resolve political and business disputes, whilst much less common than it was during the 1990s, still occurs from time to time.

Deslan Group overview

The group is substantial in national terms and has shown a strong business performance over a sustained period. There has been undisturbed profit growth year on year since 1993 and an aggressive acquisitions strategy has seen core businesses grow rapidly, particularly following the hard-fought acquisition of AIA Group in 1994. Construction and transport still contributes more than 50 per cent to profits, helped no doubt by continued good relationships with the public sector. The strategy is to continue to grow these businesses strongly, leveraging their excellent market positions, as well as the renewed focus on the trucks business.

The group is organised through a series of divisional structures, with operating companies owned by a series of holding companies, which in turn belong to the main holding company, Deslan Holdings, which is believed to be 80 per cent owned by Zubin Deslan and various family members, all of whom operate through nominees (i.e. legal entities such as companies and trusts which hold on behalf of a beneficial owner). Corporate administration appears sound, with all books up to date, meetings held and minuted, all returns filed within time and no fines or other censure or criticism from the Moldavian Corporate Authority (MCA).

Financially the group appears strong and although it undoubtedly has the funds to finance the proposed project itself, this would mean that it could do virtually nothing else – a situation that makes no sense at all given the multiple opportunities the group is presented with.

Zubin Deslan

Born in 1961. Deslan is the son of a university professor and a teacher and has five siblings. He is quiet and non-demonstrative – not your average Moldavian businessman, who tends to be a ‘larger than life’, street trader, bon viveur type. He got a first class honours in Biochemistry from Krestinberg University, followed by two years’ national service in the air force, 1983–85. His career in the Ministry of Agriculture culminated in a position as a director general of Belvin Keffl in 1989.

Deslan bought Belvin Keffl from the Moldavian government in 1991 (aged 30) apparently using finance raised from contacts he made on a short-term summer management programme at Stanford Business School in the late 1980s and grew the business from then into the conglomerate which it is today. He has successfully raised funds from FFIs in the past, including from Goldman Sachs and UBS. His acquisition of AIA Group in 1994 was bitterly contested and controversial at the time, as victory effectively handed Deslan control of the food and agricultural sectors in Moldavia, as well as giving him a substantial slice of the chemicals and construction sectors. Both Deslan personally and Deslan Group, were financial contributors to the ruling MNPP who won last year’s elections on a wide-ranging (and popular) programme of reform and liberalisation based on getting people to consign the country’s poverty-stricken communist past to the history books, and unite around a bright and prosperous future. The MNPP is bitterly opposed by the other main political party, the Moldavian People’s Power Party (MPPP), which claims that modernisation has been a disaster for the poorest, and advocates a more state-led approach to the economy to protect wages and living standards.

Information 1 – obtained from a public registry

Information 2 – obtained from the website of Transparency International

Relevant sections from Transparency International’s Anti-corruption

Index, contained in its latest annual report (1 = least corrupt):

123.Moldavia

124.Bulgaria

125.Ukraine

126.India

127.Pakistan

128.Indonesia

Information 3 – obtained from a conference call with the country manager, who obtained it orally from an attorney friend

Information 4 – obtained from a local newspaper by the country manager

Handwritten note faxed over by local manager

Information 5 – obtained from an international newspaper

FINANCIAL NEWS

But Moldavia may yet come to terms with its tumultuous past and, in particular, construct a permanent settlement betweent the state and the private sector concerning the corrupt and self-serving ways in which state assets were sold off after the demise of communism.

PAY YOUR TAXES

The recent statement by Finance minister Egbert Aldoa is a case in point. In a wide-ranging interview for CNN Business, he indicated that the Moldavian Government would no longer be looking to prosecute cases of alleged acquisition at undervalue from the 90s, as long as those suspected behave as good corporate citizens and pay their taxes here and now in the 21st century.

One person who will welcome such statements is undoubtedly Zubin Deslan, creator and CEO of the eponymous Deslan Group, a sprawling Moldavian conglomerate which is into everything from food and agriculture to mines, construction, chemicals and trucks. The previous government tried unsuccessfully to bring corruption charges against him and Agriculture Secretary Henrik Boslan in 1996 in relation to Deslan’s acquisition of the state-owned Belvin Keffl Group (a decision signed off by Boslan) but these failed due to lack of evidence and Aldoa’s ruling MNPP has shown little appetite to resurrect the case, especially since Boslan himself succumbed to terminal cancer last year and Deslan is both an eloquent and generous supporter of the ruling MNPP party.

RIGHT TRACK

Those close to the Moldavian political and business elite now believe that if the country can cement this settlement and continue with the economic reform programme, then the future would be bright, heralding prosperity and, whisper it softly, even power.

“Moldavia has some of the largest oil reserves in the region”, says Patrick Climbe, Head of the Economic Research Institute in Krestinberg. “It has minerals, a sizeable population that is set to be larger than Canada’s by 2050, and is well placed politically to act as a bridge between Russia and the West.”

But others are more sceptical and point to rampant corruption, a simmering historical enmity with neighbouring Moldachia, and an opposition party which is far from weak and which is itching to return to power and settle some old scores. “Moldavia is only ever one election away from a return to state economics and a catastrophic war with Moldachia” says Prof. Marian Divlas of the Chair of international studies at Krestinberg University. “That’s what I tell anyone who starts getting too starry-eyed about the future.”

Information 6 – obtained by country manager from local business people

Information 7 – obtained from the legal department via local lawyers after analysis of the company’s constituent documents

The Bank’s lawyers in Krestinberg, Messrs Panaca Dale, have provided the following assessment of the corporate governance levels of both BK and Deslan Group. Please note that this is the initial assessment and is subject to any further information provided by the company.

“The legal framework and company charter provide for basic shareholders’ rights such as the registration of shares in share registers, the right to transfer shares, to participate in general shareholder meetings and to elect and dismiss board members. However, there are no sufficient mechanisms to ensure protection of such rights or redress in cases of violation. Minority shareholders are not necessarily granted equitable treatment (e.g. the voting rights of different classes of shares are not well defined, insider dealing is not properly regulated etc). Stakeholders’ rights are not necessarily recognised. There are certain disclosure requirements of material information on the company, which however do not allow shareholders to get a thorough understanding of the financial situation of the company, with such information being provided on an infrequent basis. There is little transparency to third parties, which are given limited access to company financial information or its ownership structure. The company board is required to have some degree of accountability to shareholders, although the enforcement mechanisms of such requirement are overall ineffective.”

I would add two more things

The actual shareholdings of Deslan and his family appear to be through nominee companies, meaning less transparency all round.

In this regard I am led to believe that Mr. Deslan himself is prepared (even keen, some say) to follow any suggestions we may make regarding the creation of greater transparency (real and perceived).

I think an early meeting is in order.

Sincerely,

Kate Bryan

Senior Legal Advisor

Information 8 – obtained from the local public registry

Information 9 – obtained from an industry contact

Transcript of telephone conversation with Alan Greenton, a business acquaintance and former US banker with a good knowledge of Moldavia

YOU: What can you tell me about Peter Valburg?

GREENTON: Peter Valburg? Oh I know Valburg quite well. There are a few of these guys knocking around in Krestinberg and Valtana [capital of neighbouring Moldachia] and, well, what can I say? They’re very well connected, they know a lot of people and many would say – and they themselves would say – that they provide a valuable service to people wanting to do business in Moldavia for the first time. They make the introductions, they negotiate the labyrinth of regulations, they know about starting an operation, investment rules, local taxes etc. etc. Cynics, of course, would say that they’re just there to make the FPS (facilitation payments) and, where necessary, the bribes, and to provide the necessary tax deductible invoices to western companies ... And of course, they’re working it both ways. As westerners, they can hop on a plane back to Copenhagen or London or New York or wherever and sell the best deals to the highest bidder ...

YOU: So he’s corrupt.

GREENTON: Well, what’s corrupt these days? Is he walking into the prime minister’s office with suitcases full of cash? No, of course he’s not. But if a local manufacturer with some easy government contracts needs western capital equipment and a guy like Valburg sets up the deal with, say, the British company which was willing to make the largest ‘thank you’ payment, and they get some western bank to finance the whole thing, well is that corrupt? You tell me ...

Information 10 – obtained from a Google search against ‘Sarbel’

Sarbel bribes reached around the world

Evidence from key witness details millions of euros paid in bribes to officials in Nigeria, Russia and Libya

Sarbel, the engineering group at the centre of the biggest bribery scandal in Finnish corporate history, paid millions of euros in bribes to cabinet ministers and dozens of other officials in Nigeria, Russia and Libya.

The payments were made as the company sought to win lucrative contracts for engineering and transport equipment, according to court documents revealed in The Wall Street Journal today.

A ruling by a Helsinki court last month names four former Nigerian telecommunications ministers as well as other officials in Nigeria, Libya and Russia as recipients of 77 bribes totalling about €12 million (£8.6 million). Sarbel accepted responsibility for the misconduct and agreed to pay a €201 million fine decreed by the court.

The court focused on bribes between 2001 and 2004 connected to Kiki Rakkinen, a Sarbel employee who was a manager in a sales unit.

Mr Rakkinen has been charged with embezzlement and is co-operating with prosecutors.

According to separate court documents, Mr Rakkinen has told prosecutors that he knows about bribes beyond Nigeria, Russia and Libya, that were made with the knowledge of senior managers.

His evidence could lead to other criminal investigations and additional fines in other countries where Sarbel is active, including the US. Mr Rakkinen alleges he has knowledge of corruption involving Sarbel managers in more than a dozen countries, including Brazil, Cameroon, Egypt, Greece, Poland and Spain.

If Sarbel is found to have acted corruptly in certain other countries, including the US, it will also face bans on public-sector contracts.