5

Large corporations and the control of the communications industries

GRAHAM MURDOCK

INTRODUCTION

The communications industries produce peculiar commodities. At one level they are goods and services like any others: cans of fruit, automobiles or insurance. But they are also something more. By providing accounts of the contemporary world and images of the ‘good life’, they play a pivotal role in shaping social consciousness, and it is this ‘special relationship’ between economic and cultural power that has made the issue of their control a continuing focus of academic and political concern. Ever since the jointstock company or corporation emerged as the dominant form of mass media enterprise in the latter part of the last century, questions about the nature of and limits to corporate power have occupied a key place in debates about the control of modern communications. This paper sets out to review the major strands in this debate and to evaluate the contending positions in the light of recent research. Although most of my examples and illustrations will be drawn from contemporary work on Britain, the general arguments are applicable to all advanced capitalist economies.

CORPORATE CONTROL IN THE CONGLOMERATE ERA

The potential reach and power of the leading media corporations is greater now than at any time in the past, due to two interlinked movements in the structure of the communications industries—concentration and conglomeration.

As I have shown elsewhere (Murdock and Golding, 1977) production in the major British mass media markets is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few large companies. In central sectors such as daily and Sunday newspapers, paperback books, records, and commercial television programming, two-thirds or more of the total audience are reading, hearing or looking at material produced by the top five firms in that sector. Other markets, notably cinema exhibition and women's and children's magazines are even more concentrated, with the lion's share of sales going to the top two companies in each. Even areas such as local weekly newspapers where production has traditionally been highly dispersed are now showing a significant increase in concentration. In 1947 for example, the leading five publishers of national newspapers accounted for only 8 per cent of the weekly market. By 1976, their share had risen to 25 per cent (Curran, 1979, p. 64). As well as illustrating the growth of concentration within particular media sectors, this example also points to the other major source of the large corporations’ increasing control over the communications industries—conglomeration.

Conglomeration is a product of the merger movement which has been accelerating since the mid 1950s. In the ten years between 1957 and 1968 for example, over a third (38 per cent) of all the companies quoted on the London Stock Exchange disappeared through mergers and acquisitions (Hannah, 1974). Since then the pace has quickened still further. In 1967–8 for example, there were 1709 mergers among manufacturing and commercial companies. By 1972–3 the figure had risen to 2415 (Ministry of Prices, 1978, p. 16). As well as reinforcing the dominance of the leading firms in most major sectors, this ‘takeover boom’ (as it is popularly known) has produced a distinctly new kind of corporation—the conglomerate—with significant stakes in a range of different markets, which may or may not be related to one another.

S.Pearson and Son provides a good example of one of the two main types of conglomerates. Although the firm was already highly diversified by the end of the Second World War with sizeable interests in ceramics, oil, banking and local newspapers, in common with most conglomerates it has acquired its major stakes in communications since the mid 1950s. In 1957, the Group bought The Financial Times from the Eyre family and took a substantial minority holding in Lord Illiffe's press company (BPM Holdings) which is currently the country's fifth largest publishers of provincial evening papers. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s they also made a series of smaller acquisitions to strengthen their stake in the weekly and bi-weekly market, and by 1974 they had a total of 96 titles (treble the number they had in 1941) making them far and away the most important force in the sector. In the late 1960s the company branched out into book publishing with the acquisition of Longman in 1968 and the merger with the country's leading paperback house, Penguin Books, in 1970. More recently, they have diversified into the general area of leisure provision with the purchase of Madame Tussauds, and the London Planetarium in 1977 and Warwick Castle the following year. Pearson is an example of a general conglomerate whose interests in communications (although significant for the relevant media sectors) are secondary to its interests in other areas of industry and commerce. General conglomerates have recently been most active in Britain in the field of newspaper publishing with Trafalgar House's acquisition of the Beaverbrook Group, and Lonrho's purchase of The Observer and takeover of Scottish and Universal Investments with its important Scottish press interests.

Communications conglomerates on the other hand, operate mainly or solely within the media and leisure industries, using the profits from their original operating base to buy into other sectors. In Britain the profits from commercial television have provided a particularly important source of finance for this kind of diversification. In addition to operating one of Britain's five network television companies for example, the Granada Group Ltd own the country's second largest television rental chain and the fourth largest paperback publishing group, and have interests in cinema, bingo clubs, motorway service areas, and music publishing. Similarly, the Midlands contractor ATV has branched out into the music business, film production and cinema exhibition, while London Weekend Television has recently bought the major publishing house of Hutchinson with its successful Arrow paperbacks division. Other leading communications conglomerates like EMI, were built on the profits from other bases in the post-war boom in leisure and entertainment spending.

Although EMI was the dominant force in the British record industry throughout the 1950s, its activities remained concentrated in the music business and certain sectors of electronics. Then in the early 1960s the company signed The Beatles and a clutch of other beat groups, and reaped enormous profits from the subsequent pop explosion. This sudden inflow of cash provided the base for a massive programme of diversification, notably into the film and television industries. In 1966 EMI bought the Shipman and King cinema chain, and two years later they launched their bid for Associated British Pictures. Their success brought them another 270 cinemas, the Elstree Studios, a major film distribution company, and a quarter share in Thames Television, the company that had secured the lucrative London weekday franchise in 1967. By 1970, EMI had bought up sufficient extra shares to give them a controlling edge over their other main partner in Thames, Rediffusion (a subsidiary of a major industrial conglomerate, British Electric Traction). EMI continued to diversify throughout the 1970s, buying bingo halls, hotels, sports clubs, and a range of other leisure facilities. In December 1979 however, the company was itself taken over by another leading conglomerate, Thorn Electrical Industries, and a new corporation Thorn-EMI formed.

At the present time, then, the communications industries are increasing dominated by conglomerates with significant stakes in a range of major media markets giving them an unprecedented degree of potential control over the range and direction of cultural production. Moreover, the effective reach of these corporations is likely to extend still further during the 1980s, due to their strategic command over the new information and video technologies (see, for example, Robins and Webster, 1979). Nor does their influence end there. As the recent history of the BBC illustrates, in addition to the market power they wield directly, the major media corporations increasingly structure the business environment within which public communications organizations operate.

The BBC is one of the largest culture-producing institutions in Britain, and through its national television and radio networks and its regional and local studios, its products reach most members of the population on most days of the year. However, it is misleading to see the BBC as an equal or countervailing force to the leading communications conglomerates. On the contrary, their activities and goals are determinant and exercise a significant influence on the Corporation's general allocative policies. In surveying the BBC's relationship to its operating environment, however, recent commentators have tended to gloss this over and to concentrate instead on the ‘special relationship’ between the corporation and the government of the day, although, here again, some aspects have received more attention than others. Recent work has focused particularly on instances of political interference in programme making (see Tracey, chaps. 8–10, and Briggs chap. 4) and on the growth of internal controls on production as a mechanism for forestalling further intervention. Rather less attention has been given to the government's potential influence over policy through its control of the compulsory licence fee which finances the corporation's activities.

However, the level of the licence fee only sets the limit points to allocative decision making. Within these parameters the options for resource allocation and overall programme policy are crucially influenced by the BBC's involvement in markets where the terms of the competition are set by the large corporations. They determine the general level of production costs, both directly through their role as suppliers of equipment, raw materials and programmes, and indirectly by fixing the market price for creative labour and technical expertise. Hence the BBC is locked in a constant competition for talent in which the dynamics of inflation put it at a permanent disadvantage since unlike the commercial companies it cannot pass on increases in costs by raising the price of its services. On the other hand, it cannot cut production costs significantly since it is competing for audiences.

In order to sustain its claim to the compulsory licence fee and justify requests for increases, the BBC cannot let its total share of the audience slip below 50 per cent for any length of time, and so it is drawn into a battle with the commercial companies in which it has to offer comparable products. Consequently, the heartland of its popular programming (BBC 1 and Radio 1) is increasingly commandeered by the same sorts of formats and content as dominate the commercial sector, while the public-service function is increasingly concentrated in the minority sectors such as adult education and Radio 3. Nor is the BBC an isolated example. Public broadcasting in France and Italy is already under similar pressures from the newly introduced commercial sector, and West Germany seems set to follow suit in the near future.

The increasing reach and power of the large communications corporations gives a new urgency to the long-standing arguments about who controls them and whose interests they serve. As we shall see, a good deal of this debate has centred around the changing relationship between share ownership and control of corporate activity, and it is this central issue that I want to concentrate on here. Unfortunately however, discussions in this area have been dogged by loose definition so, before we examine the main strands in the debate, we need to clarify the two main terms: ‘control’ and ‘ownership’.

DEFINING CONTROL AND OWNERSHIP

Following Pahl and Winkler (1974, p. 114–15), we can distinguish two basic levels of control—the allocative and the operational. Allocative control consists of the power to define the overall goals and scope of the corporation and determine the general way it deploys its productive resources (see Kotz, 1978, p. 14–18). It therefore covers four main areas of corporate activity:

- The formulation of overall policy and strategy.

- Decisions on whether and where to expand (through mergers and acquisitions or the development of new markets) and when and how to cut back by selling off parts of the enterprise or laying off labour.

- The development of basic financial policy, such as when to launch a new share issue and whether to seek a major loan, from whom and on what terms.

- Control over the distribution of profits, including the size of the dividends paid out to shareholders and the level of remuneration paid to directors and key executives.

Operational control on the other hand, works at a lower level and is confined to decisions about the effective use of resources already allocated and the implementation of policies already decided upon at the allocative level. This does not mean that operational controllers have no creative elbow-room or effective choices to make. On the contrary, at the level of control over immediate production they are likely to have a good deal of autonomy. Nevertheless, their range of options is still limited by the goals of the organizations they work for and by the level of resources they have been allocated.

This distinction between operational and allocative control allows us to replace the ambiguous question of ‘who controls the media corporations?’ which is often asked, with three rather more precise questions: ‘where is allocative control over large communications corporations concentrated?’, ‘whose interests does it serve?’ and ‘how does it shape the range and content of day-to-day production?’.

The answer most often given to the first of these questions is that allocative control is concentrated in the hands of the corporation's legal owners—the shareholders—and it is their interests (notably their desire to get a good return on their investment by maximizing profits) that determine the overall goals and direction of corporate activity. However, as with ‘control’, we need to distinguish between two levels of ‘ownership’: legal ownership and economic ownership (see Poulantzas, 1975, p. 18–19). This distinction draws attention to the fact that not all shareholders are equal and that owning shares in a company does not necessarily confer any influence or control over its activities and policies. For legal ownership to become economic ownership, two conditions have to be met. First, the shares held need to be ‘voting’ shares entitling the holder to vote in the elections to the board of directors—the company's central decision-making forum. Second, holders must be able to translate their voting power into effective representation on the board or that sub-section of it responsible for key allocative decisions (since each share usually carries one vote, the largest holders are normally in the strongest position to enforce their wishes). As a result, economic ownership in large corporations is typically structured like a pyramid with the largest and best organized voting shareholders determining the composition of the executive board who formulate policy on behalf of the mass of small investors who make up the company's capital base. Associated Communications Corporation (the parent company of ATV Network) provides a particularly clear example of this structure. According to the last published accounts the legal ownership of the company is highly diversified with some 54.2 million ‘A’ ordinary shares in circulation, divided up among over thirteen thousand separate investors, mostly in small parcels of between a hundred and a thousand units. Economic ownership on the other hand is highly concentrated with the company's three key executives holding a majority of the voting shares. The founder and current chairman, Sir Lew Grade, has a total of 27 per cent while the two managing directors hold a further 25 per cent between them, giving the three men a numerical majority over the other voting shareholders. However, it is not necessary to hold over 50 per cent of the voting shares in order to exercise effective allocative control. Where the other main blocs of voting shares are small and fragmented, a wellorganized individual or group can assert control with less than 5 per cent.

When we are talking about the relationship between control and ownership then, we are talking first and foremost about the connections between allocative control and economic ownership. Unfortunately, as we shall see presently, a number of commentators have failed to make these crucial distinctions with the result that there has been a good deal of arguing at cross purposes. Nevertheless, when the confusions of terminology have been cleared away there remains a fundamental division of opinion over the relative importance of share-ownership as a source of command over the activities of the modern corporation and the general direction of the corporate economy.

FOUR APPROACHES TO CORPORATE CONTROL

Approaches to the control of large corporations can be usefully divided up according to the general conception of the socio-economic order that underpins them (capitalism v. industrial society) and the primary focus of their analysis (whether it emphasizes action and agency or structural context and constraint). This produces the basic classification of approaches summarized in Table 1.

Action approaches to corporate activity revolve around the concept of power. They focus on the way in which people, acting either individually or collectively, persuade or coerce others into complying with their demands and wishes. They concentrate on identifying the key allocative controllers and examining how they promote their own interests, ideas and policies. Structural analysis, on the other hand, is concerned with the ways the options open to allocative controllers are constrained and limited by the general economic and political environment in which the corporation operates. The pivotal concept here is not power but determination. Structural analysis looks beyond intentional action to examine the limits to choice and the pressures on decision making.

Table 1: Varieties of approach to corporate control

Focus of analysis |

Conception of the socio-economic order |

|

Capitalism |

Industrial society |

|

ACTION/POWER Asks the question: ‘Who controls the corporations?’ |

Instrumental Approaches stress the continuing centrality of ownership as a source of control over the policies and activities of large communications corporations. They operate at two levels: (a) At the specific level they focus on the control exercised by individual capitalists to advance their own particular interests. (b) At the general level they examine the ways in which the communications industries as a whole operate to bolster the general interests of the capitalist class, or of dominant factions within it. |

Pluralist approaches start from the position that ownership is a relatively unimportant and declining source of effective control over the activities of large modern corporations. They also operate at two levels: (a) Specific approaches emphasize the use and power of the managerial strata and the relative autonomy of creative personnel within communications corporations. (b) More general analyses stress the autonomy of media élites and their competitive relation to other institutional élites. |

STRUCTURE/DETERMINATION Asks the question: ‘What factors constrain corporate controllers?’ |

Neo-Marxist political economies focus on the ways in which the policies and operations of corporations are limited and circumscribed by the general dynamics of media industries and capitalist economies. |

Commercial laissez-faire models stress the centrality of ‘consumer sovereignty’ and focus on the ways in which the range and nature of the goods supplied is shaped by the demands of consumers expressed through their choice between competing products in the ‘free’ market. |

There has been a tendency for these two approaches to develop separately and even antagonistically. As I have argued elsewhere (Murdock, 1980) this is a false dichotomy. An adequate analysis needs to incorporate both. A structural analysis is necessary to map the range of options open to allocative controllers and the pressures operating on them. It specifies the limit points to feasible action. But within these limits there is always a range of possibilities and the choice between them is important and does have significant effects on what gets produced and how it is presented. To explain the direction and impact of these choices however, we need an action approach which looks in detail at the biographies and interests of key allocative personnel and traces the consequences of their decisions for the organization and output of production. As Steven Lukes has pointed out, the concept of power is a necessary complement to structural analysis.

To use the vocabulary of power in the context of social relationships is to speak of human agents, separately or together, in groups or organisations, significantly affecting the thoughts and actions of others. In speaking thus, one assumes that, although the agents operate within structurally determined limits, they nonetheless have a certain relative autonomy and could have acted differently. The future, though it is not entirely open, is not entirely closed either. (Lukes, 1974, p. 54)

A full analysis of control then, needs to look at the complex interplay between intentional action and structural constraint at every level of the production process.

As well as this division between action and structural approaches, the analysis of corporate control has been caught up in the basic opposition betwen what Giddens has called ‘theories of industrial society’ and ‘theories of capitalism’ (see Giddens, 1979, p. 100–1). These theories offer fundamentally opposed models of the socio-economic order produced by industrial capitalism. The basic positions began to polarize in the mid-nineteenth century with Marx on the one side, and Saint Simon and his personal secretary Auguste Comte (one of the founding fathers of modern sociology) on the other (see Stanworth, 1974).

Although both ‘theories’ start from an analysis of the economic system, they approach it in very different ways. Marx begins with the unequal distribution of wealth and property and its convertibility into productive industrial capital through the purchase of raw materials, machinery and labour power. For Marx, the defining feature of the emerging industrial order was that effective possession of the means of production was concentrated in the hands of the capitalist class, enabling them to direct production (including cultural production) in line with their interests, and to appropriate the lion's share of the resulting surplus in the form of profit. However, Marx argued, capitalists are not free to do exactly as they like. On the contrary, he suggests that they were in much the same position as ‘the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells’ (Marx and Engels, 1968, p. 40). The economic system created by the pursuit of profit has, he argued, a momentum of its own which produces periodic commercial crises and social conflicts which threaten profitability. Consequently, many of the actions of capitalists are in fact reactions—attempts to maintain profits in the face of the pressures exerted by shifts in the general economic and political system. Marx's general model, therefore, contains both an action and a structural approach to control over the cultural industries and both these strands have been pursued by later writers.

The action strand in Marxism focuses on the way in which capitalists use communications corporations as instruments to further their interests and consolidate their power and privilege. In its simplest version, this kind of instrumental analysis concentrates on how individual capitalists pursue their specific interests within particular communications companies. The second main variant, however, works at a more general level and looks at the way the cultural industries as a whole operate to advance the collective interests of the capitalist class, or at least of dominant factions within it. Marx's best-known statement of this position occurs in one of his earliest works, The German Ideology, where he argues that:

The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production…. Insofar as they rule as a class and determine the extent and compass of an epoch, they do this in its whole range, hence among other things (they) also regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age: thus their ideas are the ruling ideas of the epoch. (Marx and Engels, 1974a, p. 64–5)

As Marx saw it, then, the owners of the new communications companies were members of the general capitalist class and they used their control over cultural production to ensure that the dominant images and representations supported the existing social arrangements. Subsequent work has attempted to develop this general argument by looking in more detail at the ideological and material links between the communications industries and the capitalist class. At the ideological level commentators have tried to specify the ways in which the dominant media images bolster the central tenets of capitalism, while at the material level studies have focused on the economic and social links binding the key controllers of communications facilities with other core sectors of the capitalist class. Marx himself provided a model for these kinds of analyses in his article, ‘The Opinion of the Press and the Opinion of the People’, which he wrote for the Viennese newspaper Die Presse, on Christmas Day 1861.

The American Civil War was at its height at the time and Marx was trying to explain why the leading London newspapers were calling for intervention on the side of the South when popular opinion seemed to support the North. His answer was that intervention was in the interests of a significant sector of the English ruling class headed by the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, and that this group was able to influence the press coverage through their ownership of leading newspapers and their social and political connections with key editors.

Consider the London press. At its head stands The Times, whose chief editor, Bob Lowe, is a subordinate member of the cabinet and a mere creature of Palmerston. The Principal Editor of Punch was accommodated by Palmerston with a seat on the Board of Health and an annual salary of a thousand pounds sterling. The Morning Post is in part Palmerston's private property…. The Morning Advertiser is the joint property of the licenced victuallers…. The editor, Mr Grant, has had the honour to get invited to Palmerston's private soirées…. It must be added that the pious patrons of this liquor-journal stand under the ruling rod of the Earl of Shaftesbury and that Shaftesbury is Palmerston's son-in-law. (Marx and Engels, 1974b, p. 124–5)

By pointing to the various links between newspaper editors and proprietors and the Palmerston circle, Marx usefully underscores the need to see the ownership and control of communications as part of the overall structure of property and power relations. (As we shall see, this is an important point of difference between Marxists and the proponents of ‘the managerial revolution thesis’, who tend to focus on the balance of power within media corporations.) At the same time, however, Marx's argument illustrates the fundamental problems with this kind of instrumentalist approach.

He begins the article by asserting that the fact that the London newspapers had faithfully followed every twist and turn in Palmerston's policy provides clear evidence of his control over the press. But this argument mistakes correlation for causality. By showing that there is a close correspondence between Palmerston's views and press presentations, Marx simply poses the question of control; he does not offer an answer. Nor is one provided by his description of the economic and social ties linking press personnel to the Palmerston clique. While this exercise points to potential sources of control and influence and identifies possible sources along which it might flow, it does not show whether this control was actually exercised or how it impinged on production. This problem of inference, from patterns of ownership and interconnection to processes of control, has dogged every subsequent analysis of this type. For as Connell has rightly pointed out:

Studies of networks of directors and family ownership provide evidence not of organisation itself, but of the potential for organisation. From inferring that they could function as systems of power within business, it is a long step to showing that they do. This requires a case-by-case study. (Connell, 1977, p. 46)

Marx himself, however, never relied solely or even mainly on this type of analysis, and alongside the action-oriented strands in his work he developed a powerful structural approach.

Analysis at this level is focused not on the interests and activities of capitalists, but on the structure of the capitalist economy and its underlying dynamics. For the purposes of structural analysis, it does not particularly matter who the key owners and controllers are. What is important is their location in the general economic system and the constraints and limits that it imposes on their range of feasible options. As Marx put it in a wellknown passage:

The will of the capitalist is certainly to take as much as possible. What we have to do is not to talk about his will, but to inquire into his power, the limits of that power, and the character of those limits. (Marx and Engels, 1968, p. 188)

It is this structural strand in Marx's thought that has provided the main impetus behind the various neo-Marxist political economies of communication.

This same division between structural approaches on the one hand and actionoriented approaches on the other, is also evident in the ‘theories of industrial society’ which have provided the main counter to Marxist models of modern capitalism.

In contrast to Marxist accounts, ‘theories of industrial society’ start with the organization of industrial production rather than the distribution of property and the fact of private ownership. The central argument was already evident in the writings of Marx's contemporary Saint Simon, who saw property as a steadily declining source of power. As the new industrial order developed, he argued, ownership would become less and less significant, and effective control over production would pass to the groups who commanded the necessary industrial technologies and organizations: the scientists, engineers and administrators. This theme of the declining importance of ownership and the rise of property-less professionals as a key power group, was pursued by a number of later writers. But it found its most powerful and influential expression in Adolf Berle and Gardiner Mean's book, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, published in 1932. According to their analysis, the modern corporation had witnessed a bloodless revolution in which the professional managers had seized control. They had quietly deposed the old captains of industry and become the new rulers of the economic order—‘the new princes’. For Berle and Means:

The concentration of economic power separate from ownership [had] created new economic empires, and delivered these empires into the hands of a new form of absolutism, relegating ‘owners’ to the position of those who supply the means whereby the new princes may exercise their power. (Berle and Means, 1968, p. 116)

This argument made an immediate impact and was widely taken up in books like James Burnham's The Managerial Revolution, whose title provided the popular tag by which this thesis came to be known. This idea of a ‘managerial revolution’ in industry is still very much with us and commands support from a number of eminent political and economic commentators, including John Galbraith, who made it one of the major themes in his best-selling book, The New Industrial State.

Seventy years ago the corporation was the instrument of its owners and a projection of their personalities. The names of these principals—Rockefeller, Mellon, Ford—were known across the land…. The men who now head the great corporations are unknown…(they) own no appreciable share of the enterprise. (Galbraith, 1969, p. 22)

As we shall see later, the ‘managerial revolution thesis’ is open to a number of empirical and conceptual criticisms. Not least, it tends to blur the crucial distinctions between the levels of ownership and control we distinguished earlier.

Despite these problems, however, it has had an enormous influence on current thinking and has supported two important currents of analysis which correspond to the two levels of instrumentalism in the Marxist approach. The first of these concentrates on the balance of power and influence within individual corporations. Where Marxists emphasize the continuing power of effective possession operating directly through specific interventions in the production process or indirectly through the limits set by allocative decisions, managerialists stress the relative impotence of owners and the autonomy of administrative and professional personnel. At the second, more general level managerialism feeds into pluralist accounts of power. Where Marxists insist that the capitalist class is still the most significant power bloc within advanced capitalism, pluralists regard it as one élite among a number of others composed of the leading personnel from the key institutional spheres—parliament, the military, the civil service, and so on. These élites are seen as engaged in a constant competition to extend their influence and advance their interests, and although some may have an edge at particular times or in particular situations, none has a permanent advantage. Hence, instead of seeing the effective owners of the communications corporations as pursuing the interests of a dominant capitalist class (as in the Marxist version of general instrumentalism), pluralists see the controllers of the various cultural industries as relatively autonomous power blocs competing with the other significant blocs in society, including industrial and financial élites.

This pluralist conception of the power structure is linked in turn to the laissezfaire model of the economy which provides the basis for the structural level of analysis within the theory of industrial society. Both conceptions are dominated by the image of the market. Just as there is a competition for power and influence between institutional élites, so media corporations are seen as having to compete for the attention and loyalty of consumers in the market. And, in the final analysis, so the argument goes, it is the demands and wants of consumers that determine the range and nature of the goods that corporations will supply. Like the capitalists in Marxist accounts, the ‘new princes’ of managerialism are not free to pursue their interests just as they like; their actions and options are limited by the power and veto of consumers. This notion of ‘consumer sovereignty’ is central not only to many academic analyses but also to the rationalizations that the communications industries give of their own operations. Here are two recent examples, the first from the eminent British journalist John Whale, and the second from the American marketing analyst, Martin Seiden:

The central truth about newspapers (is) that they cannot go beyond the range of their readers. It is therefore the readers, in the end, who are the figures of power…. That is the answer to the riddle of proprietorial influence. Where it survives at all, it must still defer to the influence of readers…. The broad shape and nature of the press is ultimately determined by no one but its readers. (Whale, 1977, p. 82–5)

It is with the audience and not with the media that the power resides…. By being constantly polled, the audience determines the type of programming that is offered by television. Because the audience's attention is so essential to the success of the system, its influence over the media is exercised in its day-to-day operation rather than as some vague, intangible desire on the part of those who own the media. (Seiden, 1974, p. 5)

Having outlined the main approaches to the question of corporate control we can now begin to examine them in more detail and see how adequate they are conceptually and how well they fit the available empirical evidence.

BEYOND CAPITALISM? THE IDEA OF ‘THE MANAGERIAL REVOLUTION’

The second half of the nineteenth century saw an important shift in the nature of industrial enterprise. Whereas in the earlier part of the century most firms were owned by individuals or families, the Victorian era saw the rapid development of the joint-stock company or corporation in which entrepreneurs expanded their capital-base by selling shares in their enterprises to outsiders with money to invest. These shareholders became the legal owners of the company. As the century progressed, this new system rapidly gained ground in all sectors of industry including the major mass medium of the time—the press. With the repeal of the newspaper taxes and the changes in company law in the mid 1850s, investing in newspapers became both easier and more attractive. The next thirty years saw the launching of well over four hundred press companies and by the end of the century most publishers had adopted some form of joint-stock organization (Lee, 1976, p. 79–80). By then, a number had also begun to offer shares not only to small groups of select investors but to the general public. The first significant media company to ‘go public’ in Britain was Northcliffe's Daily Mail in 1897.

As well as dispersing the legal ownership of companies among a steadily widening group of shareholders, the rise of the modern corporation significantly altered the relationship between ownership and control. Unlike the old style owner-entrepreneurs who had actively intervened in the routine running of their enterprises, the new shareholder-proprietors tended to be ‘absentee owners’, who left the business of supervising production to paid professional managers. Marx was one of the first commentators to highlight this development, noting that:

Stock companies in general have an increasing tendency to separate this work of management from the ownership of capital…the mere manager who has no title whatever to the capital performs all the functions pertaining to the functioning capitalist…and the capitalist disappears as superfluous from the production process. (Marx, 1974, p. 387–88)

Along with other types of enterprise the press of Marx's day was also caught up in this general shift in industrial organization. Whereas in the earlier part of the century it had been common for newspaper proprietors to double as editors, as the scale of newspaper organizations increased, so more owners relinquished their control over day-to-day operations and left the routine management of their papers to full-time editors.

Marx saw the rise of professional managers simply as a further elaboration in the division of industrial labour. He did not see it as the basis for a shift in the locus of control within corporations. Although they had delegated operational control, he argued, the leading owners still retained their effective control over overall policy and resource allocation through the board of directors which they elected and on which some of them sat. Consequently, the managers’ operational autonomy (and their continued employment with the company) ultimately depended on their willingness to comply with the interests of the owners.

Marx's own awareness of the limits to managerial autonomy was underscored by his experience of working as one of the New York Daily Tribune's European correspondents. To begin with his articles were very highly regarded and when money troubles forced the paper to lay off its foreign staff, he was one of the two people retained. However, the proprietor, Horace Greely, was becoming increasingly alarmed by Marx's views and he asked the editor, Charles Dana, to sack him. Dana refused, but publication of Marx's articles was suspended for several months and soon afterwards the paper dispensed with his services on the grounds that the space was needed for their coverage of the Civil War. The owners’ interests had finally outweighed respect for Marx's undoubted journalistic skills (see McLellan, 1973, p. 284–89).

This basic imbalance of power between owners and managers has recently been re-emphasized in an interview with Sir James Goldsmith, the flamboyant proprietor of Britain's short-lived weekly news magazine, Now.

Interviewer: If the editor and you disagree, what do you do?

Goldsmith: It's the same as in any other business. If you disagree with the editor, it's give and take—and sometimes you give in, sometimes he gives in. If a disagreement becomes such that you can't live together, then the editor goes, just like a managing director would. (Dimbleby, 1979, p. 230)

Opponents of the Marxist argument might well object to this example on the grounds that Goldsmith's interventionist stance is untypical of ownermanager relations in modern corporations. However, it is by no means an isolated instance. Take for example the case of London Weekend Television. When the British commercial television franchises came up for reallocation in 1967, the company successfully bid for the contract to serve the London area at weekends. Their submission promised innovations in all major areas of programming and pledged that the company would ‘respect the creative talents of those who, within the sound and decent commercial disciplines, will conceive and make the programmes’. On this basis they attracted an experienced and highly-regarded management team headed by Michael Peacock, a former Controller of BBC 1. As economic conditions in the television industry worsened, however, the ‘commercial disciplines’ increasingly prevailed over ‘respect for creative talents’. Programme innovations were shelved and relatively unprofitable drama and arts programmes had their budgets cut and were broadcast at non-peak times. By the spring of 1969, peak-time viewing was almost completely dominated by American material, cinema films, comedy shows and successful series from other companies. Despite this concentration on relatively low-cost, high-audience programmes, however, LWT made a loss of 1.1 million pounds in its first year of operation. Then, in September 1969, under pressure from the leading interests on the board, Michael Peacock's contract was terminated. This action precipitated a crisis among the creative management and six of those in senior positions resigned. As one of them, Frank Muir (the head of Entertainment) explained to the press afterwards:

We thought we had the programme creative element built into their business board with Michael Peacock on it. But, it wasn't enough. What it boils down to is the divine right of boards to have the final say in TV programme companies.

Theorists of capitalism see this and similar instances as confirming Marx's general argument that the interests of owners operating through key members of the board, continue to determine the basic allocative policies of modern corporations. Supporters of the ‘managerial revolution thesis’ on the other hand, strongly oppose this conclusion and insist that the dispersal of shareholding and separation of ownership from management have brought about a fundamental shift in the locus of corporate control. As modern corporations expand and become more complex, they argue, only the full-time executives are in a position to keep track of developments and since they control the flow of information to the board, they can present the available options in ways that favour the policies they would like to see implemented. Moreover, with the progressive expansion of legal ownership through new share issues, the larger holders command a steadily diminishing proportion of the total and are less and less able to enforce their interests. Consequently, although the directors still formally control the corporation on behalf of the shareholders, in reality they are reduced to rubber stamping the strategies and policies devised by the managers. They have replaced owners as the primary allocative controllers.

Managerialists see this shift in the locus of corporate control as laying the basis for a new kind of advanced industrial order which Berle dubbed ‘People's Capitalism’ (Berle, 1960). According to this argument the fact that most managers own few, if any, shares in the enterprises they run separates them not only from the capitalist class but from the underlying aims and interests of that class. Berle and Means, for example, were adamant that the ‘managerial revolution’ raised ‘for re-examintion the whole question of the motive force back [sic] of industry, and the ends to which the modern corporation can or will be run’ (Berle and Means, 1968, p. 9). They were convinced that as managers were progressively released from the demands of shareholders they would develop new aims and motivations. In particular, they suggested that profit maximization would cease to be the major driving force behind industrial enterprise and that as a result corporations would become less exploitative and more socially responsible, more ‘soulful’ to use a contemporary term.

Berle and Means's general thesis gained enormously in credibility from being backed by detailed empirical evidence derived from their research into patterns of ownership and control in all 200 of the top American corporations. The results of this study are still frequently quoted today, and their approach has been widely adopted by subsequent commentators. However, a closer look at their work reveals several major problems.

Critics have attacked the managerialist argument for underestimating the continuing power of capital ownership and for failing to take adequate account of the structural constraints on corporate behaviour. Berle and Means regarded 20 per cent as the minimum holding that an owner needed to enforce his control. Consequently, if the largest identifiable holding of voting shares fell short of this, they defined the corporation as management controlled. Using this criterion, they were able to classify two-thirds of their total sample as under management control. However, there are problems with this impressive-looking finding. Firstly, the fact that they were unable to obtain reliable information on a number of companies means, as they point out, that their ‘classification is attended by a large measure of error’ (Berle and Means, 1968, p. 84). In fact, as Zeitlin has shown (1974, p. 1081–2) their data only allowed them to classify 22 per cent of their total sample and 3.8 per cent of the leading industrial corporations as definitely under management control. In the absence of reliable data either way, they simply ‘presumed’ that the rest were also manager controlled. However, this is a dubious assumption for several reasons. In the first place, the true extent of proprietal holdings is often disguised through the use of ‘nominees’ (usually banks) who hold shares on behalf of owners whose identity they are not required to declare. Prior to the take-over by Thorn of EMI, for example, both of EMI's two largest shareholders were controlled by nominees; Guaranty Nominees with 6 per cent and Bank of England Nominees with 4.6 per cent. But even where the identity of all the major shareholders is known, Berle and Means's method still leads them to underestimate the degree of potential owner control. According to the last shareholders’ list, for example, the largest holding in Thames Valley Broadcasting (the commercial radio station) was Thames Television's 19.88 per cent, which falls just short of Berle and Means's 20 per cent cut-off point for owner control. What was not apparent from the list, however, was that one of the other leading holders, EMI (with 4.52 per cent) also held the controlling interest in Thames TV which gave the company command over 24.4 per cent of the station's total shares, enough for owner control in Berle and Means's terms. This failure to take account of the interconnections between shareholders is symptomatic of a more general limitation in the managerialist approach.

As I indicated earlier, effective economic ownership depends not only on the absolute size of the largest shareholding bloc, but also on the relative dispersal of the other voting shares and on their holders’ capacity for common action and collective mobilization. Hence control is not a quantity but a social relation. Consequently, its analysis requires a dynamic perspective which takes account of the shifting balance of power between shareholders, rather than the static enumerative approach of Berle and Means.

As well as neglecting the interrelations between shareholders, Berle and Means also ignore the potential influence of other forms of capital relations on corporate behaviour. In particular, critics have drawn attention to the power of banks and other suppliers of loan capital. As Kotz has argued:

A corporation that requires a large supply of external funds, even if it is financially sound, may have to yield a certain amount of informal influence to a big lender or investment bank…. The ultimate source of power obtained by financial institutions in such situations is the threat of denying further funds, which could prevent the corporation from carrying out its plans. (Kotz, 1978, p. 21)

A good example is provided by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (ATTC), the giant communications corporation which Berle and Means singled out to illustrate the principle of management control. At first sight, it looked like a text-book example. The voting shares were very widely dispersed with the top twenty shareholders accounting for less than 5 per cent (4.6 per cent) of the total between them. Consequently, Berle and Means concluded that the corporation was under complete management control and operated independently of any significant property-owning group. However, a closer look revealed that ATTC was tied in with two of the largest owner groups in the US economy—the Morgans and the Rockefellers. At the time (1932), the Morgans’ influence extended across a quarter of America's corporate wealth, with the Rockefellers running a close second.

Both had significant banking relations with ATTC and both were well represented on the board. No less than fourteen of the nineteen members had links with other Morgan interests, with fifteen representing the Rockefeller interest (see Klingender and Legg, 1937, p. 71). How exactly the two groups influenced ATTC policy is open to dispute, but clearly the social and economic ties between them and the corporation's senior management provided convenient channels along which influence and control might potentially flow. By sticking so closely to what we might call the ‘capitalism in one company’ approach, however, Berle and Means gloss over the existence and extent of these indirect sources of influence, and present a truncated account of the relations between property ownership and allocative control.

This failure to examine the contextural constraints on corporate behaviour provides the starting point for the critiques of managerialism mounted by neo Marxist political economists. As De Vroey has emphasized:

While Managerialists just ask the question ‘who rules the corporations?’, Marxists’ main question is: ‘For which class interests are the corporations ruled?’ Here, one questions the logic of the actions, and this logic goes beyond motivations, being inherent to the mode of production and the place of the individuals within it. (De Vroey, 1975, p. 6–7)

As we saw earlier, supporters of the ‘managerial revolution’ thesis stress the fact that managers do not share the traditional capitalists’ concern with profit maximization. Since most of them have few shares in the companies they run, the argument goes, their motivations tend to revolve around career and promotion rather than profit. Their main concerns are with building up the autonomy and influence of their departments, gaining prestige and status, and advancing the ideas they favour. However, by emphasizing personal motivations this analysis conveniently neglects the ways in which managers’ actions are constrained by the economic context in which they are obliged to operate. No matter who controls the corporations, opponents argue, profit maximization remains the basic structural imperative around which the capitalist economy revolves; hence,

Professional managers have to worry about profits, just as much as the traditional tycoon…. Even if they are subjectively interested not in profits but in the growth of the firm and the power and prestige which this brings them, profits are still essential to secure this growth. Profits provide directly much of the finance for growth; they are also necessary for raising extra funds from outside. (Glyn and Sutcliffe, 1972, p. 52)

This structuralist argument also casts doubt on the idea of the ‘soulful’ corporation. This is not to say that corporations are only interested in making profits or that their support for cultural and community activities is not informed by a genuine philanthropy. However, these activities also bolster the effective pursuit of profit by enhancing the corporation's general image and deflecting criticism of its operations. Atlantic Richfield, the American oil company that owned The Observer, provides a good illustration of this mixture of motives. The company's involvements in arts patronage and social-welfare programmes have been hailed as a prime example of the ‘soulful’ corporation in action, and there is no doubt that these moves are partly motivated by a genuine concern for the quality of communal life. However, as the chairman pointed out to shareholders in 1978, they also help considerably with the main business of profit maximization.

Atlantic Richfield is aggressively seeking out the economic opportunities afforded by our free enterprise system and taking full advantage of them. Despite the social upheaval of the last few years (including increasingly critical appraisals of business), Atlantic Richfield's primary task remains what it has always been—to conduct its business within accepted rules to generate profits, thereby protecting and enhancing the investments of its owners. But…senior management recognize that the Company cannot expect to operate freely or advantageously without public approval. And today the public expects a corporation to contribute to the quality, as well as the quantity, of life—or go out of business altogether. (Atlantic Richfield, 1978, p. 27) [my italics]

Far from replacing the pursuit of profit as Berle and Means had hoped, then, corporate excursions into social responsibility have become a way of pursuing this goal more effectively in an unstable social and political climate.

Analysing the nature of these constraints on profitability and their implications for corporate behaviour provides the basis for the structuralist strand in Marxist approaches to corporate control. In contrast, the instrumentalist's current stresses the continuing centrality and power of individual owners and of the capitalist class.

PATTERNS OF OWNERSHIP: RECENT EVIDENCE

According to the most recent detailed study of the largest 250 firms in the UK economy, well over a half (56.25 per cent) have ‘an effective locus of control connected with an identifiable group of proprietary interests’ and can be classified as owner controlled (Nyman and Silbertson, 1978, p. 80). However, the composition of these proprietary interests has changed considerably over the last two decades. In 1957, almost two thirds (65.8 per cent) of the shares quoted on the London Stock Exchange were held by individuals. By 1975, this proportion had shrunk to just over a third (37.5 per cent). Over the same period, the proportion held by major insurance companies, investment trusts and pension funds, increased from 19 per cent to 42.7 per cent. There was also a small rise in the proportion held by other industrial and commercial companies and by overseas interests (Royal Commission on the Distribution of Income and Wealth, 1979, p. 141). Not surprisingly, communications corporations show the impact of these shifts somewhat unevenly.

As I have shown elsewhere (Murdock, 1980), the national press, as one of the oldest media sectors, is still largely dominated by companies controlled by the descendants of the original founding families and their associates. In fact, five out of the top seven concerns are of this type (they are: Associated Newspapers, The Daily Telegraph Limited, The Thomson Organisation, News International and S.Pearson and Son). However, the resilience of individual ownership is by no means confined to the press or to the British media. The American entertainment industries also boast a number of wellknown instances of proprietal power. They include: Mr Kirk Kerkorian, who has a 25.5 per cent stake in Columbia Pictures and a sizeable stake in another Hollywood major, MGM; and Mr William Paley, chairman and key stockholder in CBS Inc., the major music publishing and commercial broadcasting company (see Halberstam, 1976).

Proprietorial interests are also well to the fore in Britain's commercial television industry. This is a particularly relevant case given the managerialist argument that the withering-away of owner power is a developing trend which is likely to be furthest advanced in the most recently established branches of economic activity.

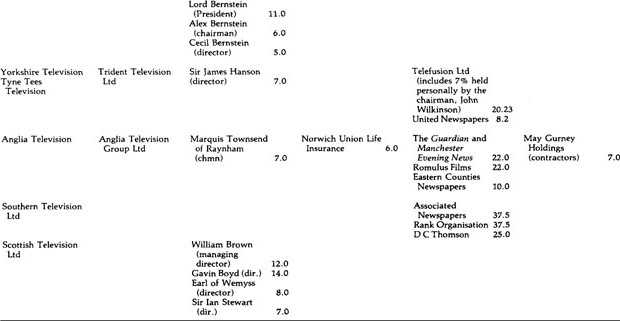

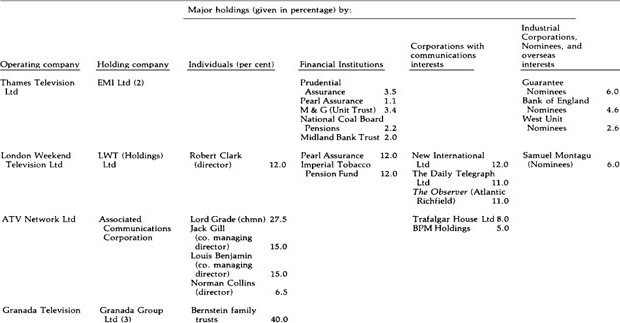

As Table 2 shows, almost all the leading corporations involved in commercial television display a highly-concentrated pattern of ownership centred on identifiable groups of proprietary interests. Indeed, five out of the eight qualify as ‘owner controlled’, even on Berle and Means's restrictive definition. In fact, the only major holding company that approximates to the managerialist model is EMI, although the presence of substantial nominee holdings make it impossible to assess the real extent of owner interests. However, the table also shows that the pattern of ownership is rather more variable than in the press. This reflects both the general shifts in share ownership since the mid-1950s when commercial television was first launched, and the specific characteristics of investment in the industry (notably the heavy involvement of newspaper companies and corporations engaged in set rental and entertainment). In three out of the eight leading concerns (Granada, Associated Communications and Scottish Television) the locus of proprietorial control lies with the leading members of the boards. In all but one of the remainder, control is held by the major institutional investors, operating through their representatives on the relevant boards. The current board of Southern Television, for example, includes the chairmen of two of the major investors—The Rank Organisation and D.C.Thomson (the Scottish press company)—and the managing director of the third, Associated Newspapers. Similarly, Lord Hartwell, the deputy chairman of LWT (Holdings), is also the chairman of one of the company's major shareholders, The Daily Telegraph Ltd, while the Anglia Group is headed by the Marquis Townsend of Raynham, vice-chairman of one of the leading investors, Norwich Union Life Insurance. As I have shown elsewhere (Murdock, 1979), these shareholding and directorial links between media companies and other leading corporations are by no means unique to television. On the contrary, they are part of an expanding network of connections binding the major communications corporations to other core sectors of British capital.

These patterns of media ownership appear to breathe new life into the instrumentalist argument in both its versions. The resilience of individual ownership fits easily into the long-standing debate about the nature and scope of proprietorial intervention in media production, while the intermeshing of communications companies and general capital re-emphasizes the question of how far media corporations operate in the interests of the capitalist class as a whole.

DYNAMICS OF CONTROL

Specific interventions and particular interests

All owners of media corporations have a basic interest in increasing the profitability of their enterprises. They may or may not also be interested in influencing the output in line with their views and values. When commentators talk about proprietorial intervention, however, they mostly have in mind this second, ideological, dimension. Concern about this reached its height in Britain between the two world wars, when the activities of press barons provided almost daily examples of owners using their papers to promote the social and political views they favoured. As Lord Beaverbrook, the celebrated proprietor of the Daily Express, told the 1948 Royal Commission on the Press, he ran the paper ‘purely for propaganda and with no other object’, although he quickly added that a paper is no good ‘for propaganda unless it has a thoroughly good financial position’, and admitted that he had ‘worked very hard to build up a commercial position’ (Royal Commission on the Press 1948, para. 8656 et seq.). For him, high circulations were a means to a mainly ideological end. For the present owners, Trafalgar House Ltd, profitability has become the primary goal, although ideological intervention is not entirely unknown. According to one inside account, Daily Express editors were still subject to pressure from the board, in the person of Victor Matthews, the Chief Executive who

would delight in pouring out home-spun wisdom at considerable length often at the busiest time of the day. This would sometimes have to be recreated by a journalist in the form of an editorial. He would hold hourlong post-mortems, and would discuss at length the main headline on the front page. (Jenkins, 1979, p. 101)

Over and above these sorts of individual interests, recent changes in patterns of ownership have added a new corporate impetus to ideological intervention.

Because of the trend towards conglomeration and the growth of institutional investment, media enterprises are increasingly linked to companies operating in socially and politically contentious areas such as oil and military technology. This, as Neal Ascherson has argued, leads to ‘the increase of potential “no go” areas for critical reporting’ and presentation, as corporations seek to use their media enterprises to promote a favourable image of their other activities (Ascherson, 1978, p. 131). According to Richard Bunce, for example, American communications conglomerates systematically use their television production wings to defend and advance their other interests. By way of illustration he cites a WBC documentary on urban mass transportation-systems which he claims stemmed directly from the fact that the company's parent corporation, Westinghouse Electric, is the country's main supplier of such systems. Similarly, he maintains that the major reason that the three main television networks turned down the first option on the ‘Pentagon Papers’ (exposing American military strategies in Vietnam) was that their parent companies were all heavily involved in servicing the war effort (see Bunce, 1976, chap. 6).

Table 2: Britain's leading commercial television companies: major voting shareholders in the relevant holding companies 1979 (I)

NOTES: (1) Information taken from the last available company depositions at the time of writing. All figures refer to the situation before the reallocation of the franchises in 1980.

(2) Date for EMI Ltd relates to the period prior to the recent take-over by Thorn Electrical Industries.

(3) These holdings may overlap to a certain extent since from the share register it is impossible to separate fully the personal holdings of the various members of the Bernstein

Although such interventions cannot be entirely discounted in a complete account of corporate power, critics have pointed out that very few instances have been convincingly documented and that those that have been are generally atypical. However, the fact that allocative controllers may not intervene in routine operations on a regular basis does not mean that there is no relationship between the owners’ ideological interests and what gets produced. For as Westergaard and Resler have pointed out, the exclusive concentration on the active exercise of control

neglects the point that individuals or groups may have the effective benefits of ‘power’ without needing to exercise it in positive action…. They do not need to do so—for much of the time at least—simply because things work their way in any case. (Westergaard and Resler, 1975, p. 142–3)

According to this view, proprietors do not normally have to intervene directly since their ideological interests are guaranteed by the implicit understandings governing production.

As I pointed out earlier, even where they have absolute operational autonomy, newspaper editors are still bound by the overall policies set by the board. As The Mirror Group told the last Royal Commission on the Press, although

the heavy hand of the proprietor has been generally removed from editors… their freedom is and must always be limited by the traditional policy of their papers…. The editor of The Times is not free for example to convert his paper into a left-wing tabloid. (Royal Commission on the Press, 1975a, p. 21)

Other commentators have pointed to the way that reporters exercise selfcensorship by holding back from investigating areas that might prove problematic for their employing organizations. Here again, the intermeshing of media and general corporate ownership has significantly increased the range of potentially sensitive areas. As one recent American analysis of interlocks concluded:

Because of the tremendous shared interests at the top coverage is limited and certain questions never get asked. Reporters who think about delving into institutional behaviour may think twice. They worry about the editing. They worry about being removed from choice beats, or being fired. (Dreier and Weinberg, 1979, p. 68)

Against this however, there are numerous instances of creative personnel asserting their autonomy and producing material that criticizes or challenges the interests of their parent conglomerates. Penguin Books provide a good example. As we noted earlier, this is a subsidiary of S. Pearson and S.Pearson and Son, a general conglomerate which owns Lazards, the prominent merchant bank, and significant stakes in a range of important British and American industrial corporations. Yet Penguin have regularly published books attacking the activities and interests of large corporations, including those to which Pearson is connected.

In an attempt to get around the contradictory evidence from particular cases the other major variant of instrumentalism has raised the level of analysis from the specific to the general, and focused on the coincidence between the values and views promoted by the general run of media output and the overall interests of the capitalist class.

Capital sociometrics: the contours of class cohesion

The general version of instrumentalism starts from the celebrated passage in Marx's German Ideology quoted earlier, and follows Ralph Miliband in arguing that although the original formulation now needs

to be amended in certain respects…there is one respect in which the text [still] points to one of the dominant features of life in advanced capitalist societies, namely the fact that the largest part of what is produced in the cultural domain is produced by capitalism; and is therefore quite naturally intended to help in the defence of capitalism [by preventing] the development of class-consciousness in the working class. (Miliband, 1977, p. 50) [my italics]

Supporters of this view have tried to bolster this somewhat bald assertion with two main sorts of evidence. Firstly, they have drawn on the results of content studies to try to show how the routine media fare produced for mass audiences legitimates the central values and interests of capitalism. At its simplest, this argument points to the ways in which media material celebrates the openness and fairness of the present system and denigrates oppositional ideas and movements. More sophisticated versions focus on the less direct inhibitions to the development of critical consciousness. They stress the way the popular media misrepresent structural inequalities and evoke the communalities of consumerism, community and nationality; the way they fragment and disconnect the major areas of social experience by counterposing production against consumption, work against leisure; the way they displace power from the economic to the political sphere, from property ownership to administration; and the way that structural inequalities are transformed into personal differences. And a certain amount of supporting evidence for these arguments can be found in a number of recent content studies, including those conducted by researchers who reject Marxist models of the media.

Having outlined these general trends in popular media output however, instrumentalists are faced with the problem of explaining them and it is at this point that they turn to the evidence on interlocks between media corporations and other key sectors of capital. The aim here is to produce a sociometric map of capitalism on the assumption that shared patterns of economic and social life produce a coincidence of basic interests and result in ‘a cluster of common ideological positions and perspectives’ (Miliband, 1977, p. 69).

Once again, recent research lends considerable support to this general argument. As I have shown elsewhere (Murdock, 1979 and 1980), the ownership pattern noted earlier for commercial television—of conglomeration coupled with growing shareholding links with other leading corporations—is increasingly characteristic of the press and the other major media sectors. Moreover, these direct ownership connections with leading capitalist interests are considerably extended by interlocking directorships. In 1978, for example, nine out of the top ten British communications concerns had directorial links with at least one of Britain's top 250 industrial corporations, and six had links with a company in the top twenty. In addition, seven out of the ten had boardroom connections with leading insurance companies, five had links with major merchant banks, and six shared directors with other significant banks and discount houses. These business links are further consolidated by communalities in social life. In 1978, for example, all fifteen of the top media corporations had board members who belonged to one or more of the élite London clubs. Moreover, the clubs most frequently favoured by directors of media corporations—Whites, Pratts, the Beefsteak, the Garrick, Carlton and Brooks's—were also among the most popular with the directors of leading financial institutions, and to a lesser extent, business corporations (see Whitley, 1973 and Wakeford et al., 1974). As well as offering further points of contact between the major media concerns and other leading corporations, club memberships provide channels for informal exchange between the leading media enterprises themselves. The older-established firms are particularly well connected through the club network. In 1978, for example, S. Pearson and Son was linked by club membership to twelve of the other top fifteen communications companies; and EMI and Associated Newspapers were each linked to ten.

At one level then, the available evidence gives reasonable support to the instrumentalist position. Media corporations are increasingly integrated into the core of British capitalism and the material they produce for mass consumption does tend to support, or at least not to undermine, capitalism's central values of private property, ‘free’ enterprise, and profit. However, this evidence only describes the general coincidence between patterns of ownership and patterns of output. It does not explain it, although instrumentalists often present it as though it did, as in the Morning Star's evidence to the last Royal Commission on the Press.

All the national newspapers have property holdings and substantial links with a wide range of financial and industrial undertakings. They are thus closely integrated with Monopoly Capital as a whole. [Hence] it is not surprising that the national capitalist newspapers strongly defend private enterprise. (Royal Commission on the Press, 1975b, p. 2)

This argument moves from correlation to causality by assuming that the capitalist class act more or less coherently to defend their shared interests. At its crudest, this produces a version of conspiracy theory. At the very least, it has to assume that the owning class intentionally pursue their collective ideological interests through their control over cultural production. There are fundamental problems with this position.

Although it ultimately depends upon an empirical account of influence and control it cannot supply the necessary evidence due to the difficulties of investigating corporate decision making at the higher levels. So in the absence of direct evidence instrumentalists are obliged to fall back on the second-hand sources provided by inside accounts together with what can be gleaned from the publicity surrounding take-overs and board struggles and scandals of various kinds. Apart from their obvious partiality, these accounts necessarily deal with atypical situations and so they cannot offer an adequate base for analysing the routine exercise of power and control. It is very easy to become fascinated by what goes on in the corridors of corporate power, by the personality clashes, the clandestine deals, the backstabbings and so on. But even if a reliable range of relevant information were available, this version of instrumentalism would still be open to the theoretical objections that it concentrates solely on the level of action and agency and that it identifies the core interests of capitalists with the active defence of key ideological tenets.

This second assumption is not absolutely necessary, however. Other variants of instrumentalism stress the centrality of economic interests and see the production of legitimating ideology as the logical outcome of the search for profits. In Ralph Miliband's words:

Making money is not at all incompatible with indoctrination…the purpose of the ‘entertainment’ industry, in its various forms, may be profit; but the content of its output is not by any means free from ideological connotations of a more or less definite kind. (Miliband, 1973, p. 202)

This version avoids slipping into a conspiratorial view of the capitalist class as a tightly-knit group of ideologically motivated men. ‘No evil-minded capitalistic plotters need be assumed, because the production of ideology is seen as the more or less automatic outcome of the normal, regular processes by which commercial mass communications work in a capitalist system’ (Connell, 1977, p. 195). Nevertheless, it remains tied to an action approach, which as Nicos Poulantzas has forcefully pointed out, ultimately identifies the origins of social action with the interests and motivations of the actors involved, operating either individually or collectively (Poulantzas, 1969).

In contrast, structuralist approaches shift the emphasis from action to context, from power to determination. Although recent neo-Marxist political economies of communications have also focused on the pursuit of profit they have concentrated on the ways that this is shaped and directed by the underlying logic of the capitalist system rather than on the identity, motivations and activities of the actors involved.

Demands and determinations

As we noted earlier, commentators differ fundamentally in the way they characterize the external constraints on corporate activity. Opponents of Marxism maintain that the range and content of cultural productions is ultimately determined by the wants and wishes of audiences. If certain values or views of the world are missing or poorly represented in the popular media, they argue, it is primarily because there is no effective demand for them. Hence, this notion of ‘consumer sovereignty’ focuses on the spheres of exchange and consumption and the operations of the market. In contrast ‘theorists of capitalism’ start with the organization of production and the way it is shaped by the prior distribution of property and wealth. They see the structure of capital as determining production in a variety of ways and at a variety of levels.