9

The political effects of mass communication

JAY G.BLUMLER AND MICHAEL GUREVITCH

Public concern about mass communication is chiefly focused on the potential effects of mass media content on audience members. Parents are anxious to protect their impressionable children from the assumed consequences of exposure to extensive portrayals of ‘sex and violence’ on television; selfappointed guardians of public morality set themselves up as watchdogs, aiming to shield society from the pernicious influence of less savoury media materials; spokesmen of numerous institutions, interest groups and social causes—ranging from the police to trade unions, industry, women's liberation, the elderly, racial minorities, etc.—often rail against broadcast and press distortion or neglect of their affairs; politicians seem to think that ten minutes ‘on the box’ are worth dozens of hours on the hustings; advertising agencies make a handsome livelihood out of their clients’ faith in the persuasive efficacy of the media. Underlying all these reactions is a common assumption: that the mass media do indeed have considerable influence over their audiences; that in this sense they are powerful. It could appear self-evident, therefore, that a priority task of communication research should be to study the effects on people's outlook on the world of the large amounts of time they spend watching television, listening to the radio, going to the movies and reading newspapers and magazines.

Among academics, however, the claims to respect of media effects enquiry are nowhere near so straightforward. Although some communication scholars, particularly those based in the United States, are heavily committed to this line of research, others tend to scorn it as misguided or unenlightening. As a result, media effects research is probably the most problematic sub-area of the field, as well as the one which has changed course most often over the years, partly in response to the ebb and flow of debate over its merits. This chapter, which deals with the political effects of mass communication, is accordingly shaped by the four-fold aim of introducing readers to:

1. Some sources of conflicting evaluations of media effects research as such;

2. the main phases in the historical evolution of different ways of investigating and interpreting media effects in politics;

3. some key examples of recent empirical work on such effects; and

4. discussion of the prospects for a convergence of approach even among opposed schools of thought towards the study of audience responses to political communications.

CONTRARY ASSESSMENTS OF MEDIA EFFECTS RESEARCH

Why is the quest for evidence of media effects on audiences so contentious? Particular lines of effects research are sometimes castigated for resting on naive theory or using unreliable methods. Yet if that was all that was wrong, the solution would lie in more mature theorizing and the adoption of improved methodologies—the familiar slow road to gradual progress in all social science endeavour. A root-and-branch scepticism towards effects research, then, must have deeper origins. We believe these can be found in a mixture of technical, ideological and cultural considerations.

Technically, whereas the design of effects research is inevitably intricate and demanding, the evidence that emerges from it often seems ‘dusty’—i.e. complex in pattern, difficult to interpret, possibly inconclusive and rarely supportive of a picture of media impact as overriding, uniform or direct. In reaction to this state of affairs, some investigators recoil as if despairing that such a difficult game can ever be worth the candle, while others welcome the very challenge of facing and gradually mastering the inherent complexities of audience response. It is true that different views of the role of theory in social science may also play a part in these contrasting reactions. Most committed effects researchers have not conceived of theory as a valid world-view to be confirmed and filled in by empirical support. They have tended instead to deploy it like a mobile searchlight, hopefully illuminating an ever-increasing range of interrelated phenomena for inclusion in wider understandings. Something like the latter position probably underlies the comment of McLeod and Reeves (1980) that:

There are abundant number of…processes and concepts that have been suggested as modifying or interpreting media exposure to effects relationship…. For the most part, the most interesting communication theory results from the unravelling of these conditions and interactive relationships, not from the simple assertions that the media set public agendas or that children learn from television. (McLeod and Reeves, 1980, p. 28)

The magnitude of the technical problems of effects research design may be appreciated by considering some of the steps an investigator of political communication impact might have to take. He would probably need to embark on at least the following activities:

1. Specify the sources of media content that he expects to exert an influence on audiences, which might be divisible into different media (TV, press, radio, inter-personal discussion, etc.), or in the case of TV, say, different programme-types (party broadcasts, news bulletins, current affairs and discussion programmes, etc.), or perhaps the appearances of different types of speakers (Conservative, Labour, Liberal, professional journalists, experts, etc.).

2. Measure the exposure of audience members to the chosen contents, no mean task in circumstances where political messages may be surrounded by much nonpolitical matter (e.g. entertainment programmes on TV) and exposure may be due more to habit than choice, entailing low levels of attention in turn.

3. Postulate likely dimensions and direction of audience effect to be tested, which could include the following foci, each presenting unique measurement problems: policy information; issue priorities; images of politicians’ qualities as leaders; attitudes to the various parties’ strengths and weaknesses; voting preferences.

4. Specify whatever conditional factors might facilitate, block or amplify the process of effect—such as, say, those of sex, age, educational background, strength of party loyalty, motivation to follow a campaign, acceptance of a medium's political trustworthiness, etc.

Yet after taking all this trouble, the research worker is unlikely to contemplate a sizeable difference of outlook between groups more and less exposed to the relevant media stimulus. It should not be concluded from the modesty of such findings that, say, political campaigning in the mass media is normally ineffectual or that messages and images transmitted through the media are powerless to alter audience perspectives. As we shall see later in this chapter, researchers who in recent years have entered the political field to harvest evidence of effects have not returned entirely empty-handed. But their results have not in the main been simple or clear-cut, and overall may be summarized as showing (1) that the media constitute but one factor in society among a host of other influential variables; (2) that the exertion of their influence may depend upon the presence of other facilitating factors; and (3) that the extent and direction of media influence may vary across different groups and individuals. As Comstock (1976) has put it, commenting especially on the impact of television:

There is no general statement that summarizes the specific literature on television and human behaviour, but if forced to make one, perhaps it should be that television's effects are many, typically minimal in magnitude, but sometimes major in social importance. (Comstock, 1976)

Ideological differences also divide certain proponents and critics of media effects research. Liberal-pluralists are initially more likely than Marxists to pursue research into the political effects of mass communication for a variety of reasons. They are more prepared to regard an election, for example, as a meaningful contest between advocates of genuine alternatives, the rival campaigning efforts of which merit study. They will tend to define political communication as a process in which informational and persuasive messages are transmitted from the political institutions of society through the mass media to the citizenry to whom they are ultimately accountable. They can thus postulate a certain measure of autonomy for the different institutional domains of society, allowing questions to be raised, then, about the influence of materials processed in the media domain on the political and other sectors. They can happily look for the impact of media materials on individual audience members, sampled in surveys or recruited for participation in experiments. They can regard the phenomenon of media power as turning very much on the influence of communication on the outlook of such individuals. Above all, they can treat the issue of media effects—their direction, strength and precise incidence—as essentially constituting an empirical question, one, that is, that is not bound to be settled in a certain way in advance.

To many Marxists, however, the conduct of effects research may seem a dubious or unnecessary enterprise. In their eyes, election campaign rivalry is merely a sort of sound and fury whipped up by Tweedledum and Tweedledee. They are unhappy about the ‘methodological individualism’ of effects research, believing that history is shaped by confrontations and shifting power relations between opposed social classes. They are little interested in many of the fine-grained informational and attitudinal media effects reported in the literature that seem to them to ignore the predominantly ideological role of mass communication in society. Thus, for Marxists the political communication process is conceived largely in terms of the dissemination and reproduction of hegemonic definitions of social relations, serving to maintain the interests and position of dominant classes—a conceptualization which does not easily lend itself to translation into the form of effects design that was sketched out in a previous page. It also follows that for Marxists the ultimate source of media power is to be located, not at the content/audience interface, but in how media organizations are owned and controlled. Finally, although most Marxists do assume that the mass media exert a significant influence on the political thinking of audience members, for them the issue of its direction is a less open question, requiring empirical probing and determination, than it is for pluralists. They are more likely to take it for granted that mass media materials are typically designed to support the prevailing status quo.

Historico-cultural differences between the United States, on the one hand, and many Western European countries, on the other, may also help to explain the much greater involvement in effects research of media academics in North America (see Blumler, 1980). In many European societies, fundamentally opposed ideological options have not only been canvassed in the writings of intellectuals, but have also been organizationally translated into partisan cleavages, involving radical challenges to prevailing distributions of wealth and power, as in the case of Socialist and Communist movements. Yet, since the end of World War II, the reality of socio-political advance towards greater equality in many of these countries has appeared slight and negligible, leaving almost unaltered the seemingly unyielding system of social stratification. Some Europeans have wondered why this should have been so and whether mass communication has played some part in dampening radical impulses among even the working-class ‘victims’ of inequality. The United States, however, is a society in which the clash of fundamentally opposed ideological and political options has always seemed muted and as if overridden by the appeal of the American dream of equality of opportunity for all. Yet in the latter part of the post-war period, one societal sub-sector after another has been disturbed by unpredictable surges of social change. Even media scholars are accustomed to describe the 1960s and 1970s as a period of ‘America in political and social transition’ (Becker and Lower, 1979), mentioning such changes in this connection as the decline of the cities, the nation's involvement in and extrication from the Vietnam war, the emergence of unconventional life-styles and sexual mores, and an ever-deepending erosion of confidence in government.

Quite different formulations of the social and political role of mass communication seem to be connected to this contrast. In Europe, academics of a Marxist and radical bent typically regard the mass media as agencies of social control, shutting off pathways of radical social change and helping to promote the status quo. In the United States, however, such formulations permeate the literature less pervasively, and the mass media are more often seen either as partial cause agents of social change; or as tools that would-be social actors can use to gain publicity and impetus for their pet projects of change; or as authoritative information sources, on which people have become more dependent as the complexities of social differentiation and the pressures of a rapidly changing world threaten to become too much for them (DeFleur and Ball-Rokeach, 1975). On the whole, a social change perspective is more suited to the conduct of mass media effects research than is a social control perspective.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF STUDIES OF POLITICAL COMMUNICATION EFFECTS

Research into political communication effects has undergone at least two major shifts of direction since its inception. In an initial phase, which lasted from approximately the turn of the twentieth century to the outbreak of the Second World War, the mass media were attributed with considerable power to shape opinion and belief. In the second period, from approximately the 1940s to the early 1960s, they were believed to be largely impotent to intitiate opinion and attitude change, although they could relay certain forms of information and reinforce existing beliefs. And in the current third stage, the question of mass media effects has been reopened; certain previously neglected areas of possible effect are being explored; and a number of freshly conceived roles for communication factors in the political process are being elaborated.

Before telling this story in greater detail, however, it may be useful to identify here certain shifts of paradigmatic or methodological character that seem more central to the state of the art as it is increasingly being conceived

- A shift from focusing on attitudes and opinions in the study of media effe to a focus on cognitions. Some examples of studies which represent this new emphasis will be presented on pp. 250–60. This change of focus raises, however, an important question, namely whether changes in cognitions are, indeed, prerequisites for changes in attitudes. While there is no doubt that the two are related, the causal links between them, so far little explored, may be rather

- A shift from defining effects in terms of particular changes to defining them in terms of a structuring or re-structuring of cognitions and perceptions. This is related to the previous shift, and is probably most clearly demonstrated in research into the so-called ‘agenda-setting function’ of the mass media, as well as the role of the media in audience ‘constructions of social reality’.

- A proliferation of models of the mass communication process, which have yielded alternative definitions of the nature of effects. The linear model, which specified the components of the communication process as comprising a source, a channel, a message and a receiver, and focused on changes in receivers’ mental states induced by stimuli relayed through prior phases of the process, has been complemented by other approaches, including: ‘uses and gratifications’ studies, in which the emphasis is placed on members of the audience actively processing media materials in accordance with their own needs (Blumler and Katz, 1974); convergence and co-orientation models, which emphasize the exchange of information among individuals in interaction so as to move towards a more common or shared meaning (McLeod and Chaffee, 1973); and a ‘chain reaction’ model of communication effect, in which the impact of the mass media is found not only in the addition of effects upon individuals but also in how other people throughout the social structure react to the influenced individuals’ example (Kepplinger and Roth, 1979).

- In considering the sources of communication effect, some shift away from an earlier preoccupation with partisan advocates, as originators of messages that might or might not influence voters, to an interest in the less purposive but potentially more formative contributions to public opinion that stem from the political news and reports fashioned by professional communicators. In the earlier view, the professionals were conceived of chiefly as ‘gatekeepers’, admitting or shutting out those messages of advocates that might eventually affect the audience. In recent work, however, they figure more often as ‘shapers of public consciousness’ in ways that may even dictate what advocates must do to stand a chance of winning electoral acceptance.

- A broadening of focus away from the near-exclusive concentration of earlier research on election campaigns, as sites of measurable political influence, to the study of political effects of media coverage in a variety of more everyday non-election circumstances as well.

This last point merits further elaboration. Since highly influential impressions of the scope of the mass media to affect voters’ political views have often stemmed from research into election campaigns (in the United States and elsewhere), it is worth noting some of the properties that explain their attraction as a repeated object of study. To begin with, an election is a special, infrequent, yet quite decisive event, during which members of the electorate are subjected to greater outpourings of overtly political communication than at almost any other time. This enables researchers to prepare their fieldwork well in advance. It also produces an outcome (i.e. votes cast for different political parties) which is known, exact, measurable and can be readily related to measures of other variables. Findings of successive campaigns can also be related to each other, thus yielding measurements of trends over time. Moreover, since an election campaign is an occasion for the launching of intensive attempts at persuasion, researchers can not only observe how voters sample and react to the various political offerings, but also put their theories about such processes to a stringent empirical test.

Two limitations of this focus have also attracted criticism. One is that it directs attention to short-term effects (over the campaign period) at the expense of the more gradual cumulation over a longer span of time of media influences on people's political beliefs. Another is that it deals only with manifestly political messages and ignores the more diffuse but possibly more pervasive ideological implications of other forms of media content—such as soap operas, family comedies, adventure serials, advertisements, etc. Some social scientists, however, have attempted to counteract these shortcomings. For example, long-term panel designs, involving interviews with the same voters across several elections, are becoming more common. And at least one major American research programme is devoted to the task of what its initiators call ‘cultivation analysis’, i.e. an attempt to determine how far certain descriptions of social reality, shown by content analysis to be projected frequently in popular television programmes of all kinds, are accepted as valid by heavy viewers of the medium. Meanwhile, the field continues to develop partly (though not so exclusively as in previous times) through studies of campaign effects. This is understandable, for when citizens are placed in a situation of electoral choice, a whole host of political orientations—information levels, attitudes to parties and leaders, impressions of the issues of the day, policy preferences, perceptions of the wider political system—are brought to the surface and exposed to possible influence.

WHEN THE MASS MEDIA SEEMED OVER-RIDINGLY POWERFUL

The assumption, widely accepted before the 1940s, of massive propaganda impact for the persuasive contents of the mass media, and a concern to test this through effects research designs, had many sources. There was the seeming ease with which World War I war-mongers and Fascist regimes in Europe of the 1930s had manipulated people's attitudes and bases of allegiance and behaviour. That impression was compatible with theories of mass society, current at the time the study of media effects began to take shape, which postulated that the dissolution of traditional forms of social organization under the impact of industrialization and urbanization had resulted in a social order in which individuals were atomized, cut off from traditional networks of social relationships, isolated from sources of social support, and consequently vulnerable to direct manipulation by remote and powerful élites in control of the mass media. Thus, the explosive growth of the media at the beginning of this century, and the global socio-political upheavals in which they were perceived to have played a part, lent urgency to the need to explain systematically and scientifically the role of this new social force and the mechanisms of its power and influence. However, an interest in the effects of assumed-to-be powerful media developed from more ‘benign’ and pragmatic concerns as well. It was hoped, for example, that the potential of the media could be used for civic education, cultural enlightenment and the diffusion of socially beneficial innovations, while advertisers and politicians hoped to learn more about the design of media messages for marketing purposes and political mobilization. The emergence of effects research in response to both policy problems and practical applications was further facilitated by the academic development of socialpsychological concepts, techniques of measurement and statistical methods of survey sampling and data analysis. Once the notion of ‘effects’ was equated with authoritarian, benevolent or competitive actors initiating changes in audience members’ attitudes and opinions, it was almost inevitable that social psychology should become its main disciplinary home.

SOME EXAMPLES OF EARLY ELECTION STUDIES DESIGNED TO TEST THE PRESUMPTION OF MEDIA POWER IN POLITICS

Perhaps the most famous election study conducted in the 1940s was the one carried out by Lazarsfeld, Berelson and Gaudet on the 1940 US Presidential elections, and published under the title, The People's Choice (1944). This investigation found that only limited change had occurred during the campaign. About half the electors knew six months before the elections how they would vote, and maintained their party preferences throughout the campaign. Another quarter made up their minds after the parties’ nominating conventions in the summer. Only about a quarter of the voters made their decisions during the supposed period of the campaign. Yet political messages seemed little involved even in their decisions. On the whole, late deciders and switching voters paid less attention to the campaign than did more stable ones. Findings concerning the tendency of voters to expose themselves selectively to political messages, i.e. to attend more to political spokesmen and messages with which they agreed than to those of the opposite side, also emerged from this study.

Later in Britain, Trenaman and McQuail (1961) conducted a most carefully designed study of the General Election campaign of 1959. According to their findings, attitudes (as distinct from votes) did undergo a definite swing (in fact favouring the Conservatives), yet no significant association could be found between that movement of opinion and how the voters had followed the election campaign through any of the communication channels they used. In the authors’ words: ‘within the frame of reference set up in our experiment, political change was neither related to the degree of exposure nor to any particular programmes or argument put forward by the parties’ (p. 191).

The image of an election campaign as an occasion for parties and leaders effectively to persuade and influence voters seemed, then, to have been exploded by these and similar studies. Little wonder that two social scientists were moved to remark when discussing this vein of research: ‘After each national election students of political behaviour comment on how little effect the mass media appear to have had on the outcome’ (Lang and Lang, 1966, p. 455).

REINFORCEMENT AS THE MAIN EFFECT

The leading investigators of campaign communication did not stop short, however, at presenting their finding of little or no communication effect on the voters. They also sought to explain why this was so. Out of these efforts emerged the reinforcement doctrine of political communication impact. This doctrine had several dimensions.

First, the typical outcome of the communication experience was succinctly expressed by Joseph Klapper (1960) in his overview of the then available literature on media effects: ‘Persuasive mass communication functions far more frequently as an agent of reinforcement than as an agent of change’ (p. 15). In other words, Klapper maintained, when people are exposed to mass media coverage of political affairs they are more likely to be confirmed in their existing views than to be fitted out with new or modified ones.

Second, Lazarsfeld and his colleagues, in their study of the 1940 Presidential election, described the spirit in which voters supposedly attended to political materials thus:

Arguments enter the final stage of decision more as indicators than as influences. They point out, like signboards along the road, the way to turn in order to reach a destination which is already predetermined…. The political predispositions and group allegiances set the goal; all that is read and heard becomes helpful and effective in so far as it guides the voter towards his already chosen destination. The clinching argument thus does not have the function of persuading the voter to act. He furnishes the motive power himself. The argument has the function of identifying for him the way of thinking and acting which he is already half-aware of wanting. (Lazersfeld et al, 1944, p. 83, 2nd edn)

Consequently, certain mechanisms of audience response to political messages were invoked to explain the reinforcement process. Given such labels as selective exposure, selective perception and selective recall, their linking thread was the idea that many people used their prior beliefs, both as compasses for charting their course through the turbulent sea of political messages, and as shields, enabling them to rehearse counter-arguments against opposing views.

Third, it was recognized, of course, that there was a group of ‘floating voters’ whose prior political anchorages were not firm enough to conform to this reinforcement model. Nevertheless, the findings of early research seemed to suggest that political persuasion was virtually irrelevant to many members of this group who, because they tended to be less interested in political affairs, were also less likely to be reached by political messages.

Finally, a key linchpin of this edifice of interpretation concerned the role of party loyalty in mass electoral psychology. It was assumed that most voters tuned in to political communication through some underlying party allegiance. Typically, this would (a) be acquired early in life; (b) persist through one's lifetime; (c) be echoed among many members of the individual's social circles, such as his family, friends, workmates and so on; and (d) guide the majority of the electorate through the maze of issues and events which appear on the political stage.

A ‘NEW LOOK’ IN POLITICAL COMMUNICATION RESEARCH

The reinforcement doctrine of political communication reigned supreme and virtually unchallenged in academe for a number of years. Even sceptics (e.g. Lang and Lang, 1966), who considered that the dominant perspective overlooked important media roles in shaping public opinion between elections, tended to accept the validity of its interpretation of short-term campaign processes. For example, they tended to agree that ‘the minds of most voters’ were likely to be ‘closed even before the campaign opens’. And since electioneering politicians would be striving mainly to ‘activate partisan loyalties’, the campaign period was ‘inherently…less a period of political change than a period of political entrenchment’ (pp. 456–7).

It is striking to find, therefore, that from the late 1960s onwards an increasing number of investigators began to proclaim that the book on political communication effects should not be closed after all. The literature began to resound with ever more frequent references to a ‘new look in political communication research’ (Blumler and McLeod, 1974), to ‘new strategies for reconsidering media effects’ (Clarke and Kline, 1974) and even to ‘a return to the concept of powerful mass media’ (Noelle-Neumann, 1974). This new mood reflected three ground-swells of change, each undermining an essential prop of the reinforcement doctrine. These changes inhered in trends in the political environment, in the media environment and in the academic community itself.

Changes in the political environment

The reinforcement doctrine of political communication was part and parcel of an overall view that placed far more emphasis on the underlying stability of the world of politics than on its flux. As Lazarsfeld (1948) put it (p. xx, 2nd edn): The subjects in our study tended to vote as they always had, in fact as their families always had.’

Nowadays, however, party loyalty, once the linchpin of electoral psychology, seems to have lost much of its power to fix voters in their usual places. Political scientists in one democratic country after another have documented evidence in recent years of accelerating rates of electoral volatility. In the US, for example, there has been a steady downward trend in ‘Presidential elections since 1952 (only slightly reversed in 1976) in the capacity of self-disclosed ‘party identification’ to predict how people will actually vote. There has also been a concomitant rise in the number of those identifying themselves as ‘Independents’. Similar trends have been reported from Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Belgium and Holland. For Britain, Butler and Stokes (1974) have assembled an impressive array of evidence indicating ‘far greater volatility of party support’ in the 1960s than in earlier post-war years. Continuing their work into the 1970s, Crewe (1973 and 1976) has documented further falls, both in shares of the eligible electorate obtained by the Conservatives and Labour at successive elections, and steep declines (ranging from 46 per cent in 1964 to 23 per cent in 1974) in the percentages of voters professing to be ‘very strongly’ identified with some political party.

Moreover, a number of signs suggest that the combination of weak partisanship and higher volatility rates is no passing phenomenon. For one thing, the power of social class to predict the ultimate destination of voters’ ballots is on the wane. That means that people are less likely to encounter a consistent and consistently reinforcing pattern of party loyalties in the work and social circles in which they move. For another, family socialization processes may no longer be capable of transmitting life-long partisan affiliations from parents to children as effectively as had been supposed in the past. It is striking to note in this connection not only that the number of Independent identifications among new entrants to the US electorate went up steadily from 1952 to 1972, but also the lack of evidence that as the newly eligible mature politically they are abandoning their Independent stances for some form of partisan affiliation. So far at least, as they age, the new electors are remaining as Independent-minded as they were when they first acquired voting rights.

It is also important to note that the enlarged group of floating voters can no longer be regarded as consisting only of people who have opted out of the political communication market. Rather are they quite often at least as well informed and politically interested as the typical party loyalist. Some recent studies have even shown a greater use of media information by those making up their minds how to vote during an election campaign than by those with stable preferences throughout a campaign period (Chaffee and Choe, 1980).

There are also indications that more people may be judging political affairs in ways that cut across party lines. They may think in terms of the issues which matter to them, or may look to attractive leadership personalities, or simply respond to political parties with grudging scepticism and mistrust. These increase the uncertainties with which the parties are confronted during election periods, and the parties often respond by redoubling their electioneering efforts and by putting themselves in the hands of public relations and advertising professionals. In these conditions, the probability that political communication will exert an influence appears to increase.

Changes in media environment

At the same time that voters were becoming more footloose, developments in the media were re-shaping the sources of people's political information and impressions. The most important of these was the increasing prominence of television as a medium of political communication.

In terms of the audience, the intervention of television into politics has been dramatic. There is increasing evidence not only that television has by now established itself as the prime source of information about political and current affairs for the majority of the population, but also that reliance on it to follow political arguments and events is particularly heavy and widespread at election times. But more important than its overall dominance is how television has helped to restructure the audience for political communication in ways that are at odds with the reinforcement thesis. First, television reaches with a regular supply of political materials a sector of the electorate that was previously less exposed to these materials. In Katz's (McQuail, 1972, p. 359) words ‘Large numbers of people are watching election broadcasts not because they are interested in politics but because they like viewing television.’ Katz supposed that the forging of a special relationship between television and the less politically-minded electors was largely beneficial: Television has “activated” them; they have political opinions and talk to others about them. It can be demonstrated that they have learned something—even when their viewing was due more to lack of alternatives than choice.’ But more important, the less interested and less well-informed also constitute a new site for persuasion, since their defences against persuasion are liable to be relatively frail.

A second consequence of the coming of television has been a reduction in selectivity in voters’ exposure to party propaganda. A medium which is constitutionally obliged to deal impartially with all recognized standpoints, and which offers favourable time-slots for the screening of the parties’ broadcasts, affords little scope for viewers selectively to tune in only to their side of the argument. Moreover, innovations in the formats of election broadcasting, such as face-to-face debates between party leaders, as between the Presidential candidates in the US, further reduce the possibilities of selective exposure.

But perhaps the most potent consequence of television's intervention into politics stems from its seemingly most innocuous feature—its need to maintain an above-the-battle stance in its relationship to party-political conflict. Since broadcasting may not support individual parties, it is obliged to adhere to such non-partisan—perhaps even anti-partisan—standards as fairness, impartiality, neutrality and objectivity, at the expense of such alternative values as commitment, consistent loyalty and readiness to take sides. Thus television may tend to put staunch partisans on the defensive and help to legitimate attitudes of wariness and scepticism towards the politicial parties. Perhaps that explains why some writers have postulated a causal connection between the ascendancy of television and increasing electoral volatility. Butler and Stokes (1974), writing about Britain, for example, conclude: ‘It should occasion no surprise that the years just after television had completed its conquest of the national audience were the years in which the electoral tide began to run more freely.’ (p. 419, 2nd edn)

Changes in conceptualizing media effects

The third major impulse feeding the renewed interest in the impact of the mass media has been a shift in the conceptual underpinnings of political effects inquiry. In the earlier post-war years, political communication research was almost coterminous with persuasion research. More recently, however, greater interest has been shown in the cognitive effects of political communication. Instead of focusing on attitude change through exposure to persuasive messages, researchers, pointing out that much political output of the mass media comes in the form of information, have aimed to analyse the political impact of mass communication in terms of its informationtransmittal function.

This observation accords with a certain feature of audience psychology. Where overt persuasion is recognized, audience members may be on their guard. But media contents may be received in a less sceptical spirit if people perceive them as information, i.e. as if they have no specific axe to grind. Indeed, when people are asked why they follow political events in the mass media, they tend to give ‘surveillance’ reasons more often than any other, as illustrated in the following table, which comes from Blumler and McQuail's (1968) study of the 1964 British General Election.

Table 1: TV owners’ reasons (per cent) for watching party election broadcasts:

1. To see what some party will do if it gets into power |

55 |

2. To keep up with the main issues of the day |

52 |

3. To judge what political leaders are like |

51 |

4. To remind me of my party's strong points |

36 |

5. To judge who is likely to win the election |

31 |

6. To help make up my mind how to vote |

26 |

7. To enjoy the excitement of the election race |

24 |

8. To use as ammunition in arguments with others |

10 |

In addition, a number of recent studies of mass communication content have produced evidence of ‘patterning and consistency in the media version of the world’ (McQuail, 1977, p. 81). The argument here is that the mass media, on the whole, present a consonant view of certain portions of social reality (e.g. in reporting of race relations, industrial relations, deviance, etc.), thus rendering one view dominant, and encouraging audience members to accept it as if ‘obvious’ or ‘natural’.

The crucial conceptual distinction that has arisen from these reflections is between attitudes and cognitions. As Becker, McCombs and McLeod (1975) have defined these terms: ‘Attitudes are summary evaluations of objects by individuals’; ‘cognitions are stored information about these objects held by individuals’. They recognize that evaluations may be based on cognitions and that their interrelations may be complex, but they suppose that cognitions can be measured independently of attitudes and can be assessed ‘against some external objective criterion of communicated information’. Hence, the shift in research focus towards a greater stress on how the mass media project definitions of the situations that political actors must cope with, than on attitudes toward those actors themselves.

Probably the most representative example of this approach can be found in attempts to study the so-called ‘agenda-setting function’ of the mass media. These aim to explore what it means to have a media system that determines which issues, among a whole series of possibilities, are presented to the public for attention. The central concern of agenda-setting research is to test the hypothesis of a ‘strong positive relationship between the emphases of mass media coverage and the salience of these topics in the minds of individuals in the audience’ (Becker, McLeod and McCombs, 1975, p. 38). What is more, the relationships involved are assumed to be causal. As Shaw and McCombs (1977) have put it in a book entirely devoted to this type of research: ‘increased salience of a topic or issue in the mass media influences…the salience of that topic or issue among the public’ (p. 12). As such formulations imply, the bulk of agenda-setting studies have focused on ‘issues’—their prominence and frequency of display in media portrayals in comparison with their place in audience members’ orders of priority. Certain other concerns have also occasionally featured in such research, however, including studies of (a) popular awareness of proposed solutions to the problems arising in key issue domains; (b) how issues get into media agendas (say, from voters’ prior concerns, or through politicians’ speeches and pronouncements, or via professional journalists’ own outlook on society); and (c) the impact of agenda setting on voting behaviour. This last focus reintroduces the complexity of the relationship between attitudes and cognitions. If, for example, immigrants are portrayed in the media as sources of social conflict and problems for society, white audience attitudes toward them may eventually become less favourable (Hartmann and Husband, 1974). Or take the case of American television coverage of the Vietnam war: if in the late 1960s Americans perceived US armed forces as losing ground in the war, even erstwhile hawks might have eventually lost their appetite for continuing involvement (Braestrup, 1977). Thus, media portrayals of social reality may ultimately induce attitude changes towards the various issues portrayed.

SOME EXAMPLES OF RECENT WORK ON POLITICAL COMMUNICATION EFFECTS

The perspectives described above have so far been presented in terms of possibilities of media impact. But what evidence have researchers managed to produce of media effects on the political outlook of audience members? Some examples of recent studies and findings are outlined below.

Agenda setting during the American Presidential election of 1972

According to agenda-setting theory, an audience member exposed to a given medium's agenda will adjust his or her perceptions of the importance of political issues in a direction corresponding to the amount of attention paid to those issues in that medium. A problem that may interfere with attempts to test this hypothesis arises when there are few or no differences between different media in the issues emphasized by them. In such a case there will be no ‘variance’ to measure.

During the American Presidential election of 1972, however, McLeod, Becker and Byrnes (1974) managed to conduct an agenda-setting study in a city (Madison, Wisconsin) which was served by two rather different newspapers—one quite conservative in outlook, the other more liberal. A content analysis of the papers confirmed that their election agendas were indeed different: the more conservative paper devoted more space to America's world leadership and to the theme of combating crime, while the liberal paper paid more attention to the Vietnam war and the theme of ‘honesty in government’.

The investigators’ task was to devise a procedure which would test whether the issue priorities of readers of the two papers diverged along lines similar to those of the papers they read. Thus, they had to relate exposure to the different newspapers to a measure of agreement with the issue agenda set by the papers. They interviewed two samples, one of first-time young voters and another of older voters. For the members of both samples, in addition to finding out what papers people read and their rank ordering of the importance of six campaign issues, they ascertained the degree of partisanship, interest in the campaign and degree of reliance on the press as an election-information source.

The findings were mixed. Generally, the data supported the agendasetting hypothesis in the case of the older sample, while the results for the younger sample were in the right direction, though falling short of statistical significance. That is, readers of the conservative paper put more stress on problems of crime and America's role in the world than did readers of the liberal paper, who gave more weight to Vietnam and corruption in government. Less interested voters seemed more open to agenda-setting influence than were the more politically involved ones. Those who were more dependent on the press as an information source were also more influenced by their paper's agenda. The authors concluded that there might be:

two different types of agenda-setting, one a kind of scanning orientation process common to the less involved voters of all ages, and the second a kind of purposive justification confined to the older respondents whereby poorly informed partisans with strong political commitments scan their newspapers as means of filling in information required by that commitment. (McLeod, Becker and Byrnes, 1974, p. 161)

Television and attitudes to the Liberal Party in the British General Election of 1964

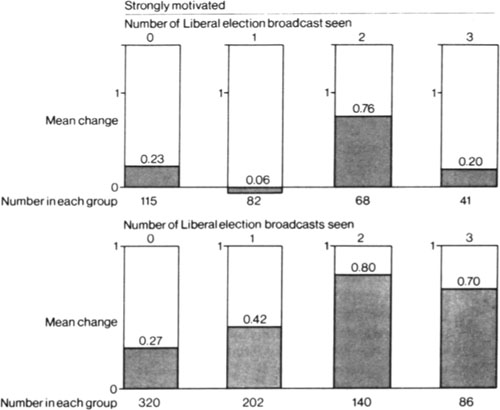

Blumler and McQuail (1968) interviewed a sample of Yorkshire voters before and after the British election campaign of 1964. Their findings were among the first to call into question the presumed supremacy of the reinforcement doctrine. Two special features of their study proved crucial. They traced movements in voters’ attitudes toward the Liberal Party, as well as to the Conservative and Labour Parties, and they devised a measure of the strength of voters’ motivation to follow the election on television. Their assumption was that exposure to campaign messages would have different effects on those who viewed out of political interest, from those who watched political programmes simply because they see a lot of television generally and have little else to do at the time.

As in the British 1959 election study that preceded it (Trenaman and McQuail, 1961), the results showed little sign of an impact of campaign exposure on voters’ attitudes to the Conservative and Labour Parties. The relationship between television use and changing attitudes toward the Liberal Party, however, was strikingly different. Overall, attitudes toward the Liberals had improved during the campaign—on average by about half a point on a +5 to—4 scale. When, moreover, the sample was divided according to the amount of exposure to political broadcasts on television, it was found that the rate of shift in favour of the Liberals progressively increased as levels of exposure to Liberal Party broadcasts increased.

Next, strength of motivation to follow the campaign was injected into the analysis. Its effect is shown in Figure 1 (p. 252), which deals separately with those who were rated strong in motivation to follow the campaign, and those whose motivations were medium or weak. The figure suggests that the introduction of a motivational variable has transformed a modest relationship between television exposure and pro-Liberal shift into a strong relationship, and one that was concentrated among the less interested voters. The zig-zag pattern for the more interested voters indicates that there was no consistent pattern between the development of pro-Liberal views and the number of Liberal programmes viewed. But among the less interested (see bottom bars of the figure) there was a strong and progressive relationship between exposure to Liberal programmes and a pro-Liberal shift. The implication is that viewers who were in the audience less out of political interest and more because of attachment to their television sets were most open to influence in their attitudes toward a party about which at the outset they probably had little knowledge and few well-formed opinions.

Figure 1a In the sample as a whole, high exposure to Liberal election broadcasts went with attitude change in favour of the Liberal Party

Figure 1b The association between pro-Liberal shift and exposure to Liberal broadcasts was confined to those respondents whose motivation for following the campaign was medium or weak

American newspaper endorsements of Presidential candidates

Preoccupation with the role of television in political communication, especially during election campaigns, may cause the role of another important communication channel, the press, to be overlooked. John Robinson (1974) has argued that the potential influence of the press should not be slighted, especially since newspapers are free to take a political stand, in contrast to television, which is obliged to present all sides of the contest and to assume a ‘neutral’ stance. In his words (p. 588): The newspaper endorsement is a direct message, which appears to reduce the confusing arguments of the campaign to a single conclusion.’ But can this have an effect? The title of his article, The Press as King-maker, provocatively indicates Robinson's answer. This reports his reanalysis of national survey data for five Presidential elections (1956–72) in which the percentages of respondents voting for the Democratic candidate were calculated according to the candidates endorsed by the newspapers those respondents read. However, since the choice of newspaper may depend, in part, on the reader's political preference—a factor which, if not controlled, may obscure the potential influence of the newspaper—the respondents were divided into three subgroups according to their prior party identifications: Republicans, Democrats and Independents. For Republicans, for example, Robinson aimed to see whether, among those individuals taking a paper endorsing a Democratic candidate, there would be more Democratic votes than among those taking a Republican-supporting newspaper.

Table 2 summarizes the results. It presents the percentages of individuals voting for the Democratic candidate among readers of Democratic-supporting, neutral and Republican-supporting newspapers in the three sub-groups determined by prior party preference.

Table 2: Percentages of electors voting for the Democratic Presidential candidate by newspaper endorsement and by party identification, 1956–72

A key column for each group of respondents is the one labelled ‘difference, Democratic-Republican’. This records for each election year the excess of Democratic voters coming from readers of Democratic papers over readers of Republican papers. For example, in 1956, 84 per cent of the Democrats reading a paper endorsing the Democratic candidate, Adlai Stevenson, voted for him; 73 per cent of the Democrats reading a paper endorsing the Republican candidate, Dwight Eisenhower, voted Democratic. Thus, the difference in the rates of support for Stevenson between Democrats reading Democratic and Republican newspapers was 11 per cent.

It can be seen that out of fifteen comparisons, the differential of support for the Democratic candidate among readers of Democratic papers exceeded that for readers of Republican papers in nine cases (that is, wherever a plus sign appears in the difference column). Over all cases the average differential was 9 per cent. Among Independents, the differential was typically much higher—averaging 20 per cent across five elections, suggesting that they were especially likely to vote in line with their newspaper endorsements.

Perhaps two conclusions may be drawn from this evidence: first, that people are more open to influence when exposed to a fairly consistent point of view on a given matter; and second, that on this occasion it was the originally less committed voters who were most responsive to such a source of influence.

Media influence on trust in government

Although much political communication research focuses on election campaigns, some social scientists have argued that the periods between elections are just as crucial for understanding the role of the media in the political life of society. This is reflected in the increasing research attention given in recent years to the influence of styles of political reporting on people's faith in their political institutions. Kurt and Gladys Lang (1966) were the first to postulate such an influence. In their words,

The mass media, by the way in which they structure and present political reality, may contribute to a widespread and chronic distrust of political life. Such distrust is not primarily a mark of sophistication, indicating that critical ‘discount’ is at work. It is of a projective character and constitutes a defensive reaction against the periodic political crises known to affect a person's destiny as well as against what are defined as deliberate efforts to mobilise political sentiment…. How, we may ask, do the media encourage such distrust?…The answers must be sought in the way in which the mass media tend to emphasize crisis and stress it in lieu of the normal processes of decision making. Such distrust also has its roots in the complexity of events and of problems in which the mass audience is involved. For instance, since viewers bring little specialized knowledge to politics, even full TV coverage of major political events does not allay this distrust. In fact it may abet it. (Lang and Lang, 1966, pp. 466–7)

Attempts to explore these matters empirically started when opinion polls in several countries began to reveal steep downward trends in the readiness of voters to trust their political leaders’ management of affairs. A further boost to this line of enquiry stemmed from the Watergate affair.

One example of such research is a study by Michael J. Robinson (1976), an American political scientist who shared the suspicion that certain features of television news-reporting could have been responsible for the sharp decline of popular trust in government in the United States in recent years. He summarized his expectations as follows:

My recent work in television has forced me to build a yet untested theory concerning the growth of political illegitimacy. I have begun to envision a two-stage process in which television journalism, with its constant emphasis on social and political conflict, its high credibility, its powerful audio-visual capabilities and its epidemicity, has caused the more vulnerable viewers first to doubt their own understanding of their political system…. But once these individuals have passed this initial stage they enter a second phase in which personal denigration continues and in which a new hostility toward politics and government also emerges. Having passed through both stages of political cynicism, these uniquely susceptible individuals pass their cynicism along to those who were at the start less attuned to television messages and consequently less directly vulnerable to television malaise. (Robinson, 1976, p. 99)

Table 3: Respondents’ views as to whether or not Congressmen lose touch with constituents after election

|

GROUP A Those not relying on television |

GROUP B Those relying on television |

GROUP C Those relying only on television |

Percent believing |

47% |

57% |

68% |

Congressman does lose touch with constituents |

(402) |

(675) |

(122) |

Controlling for educational level of respondent |

|||

Less than 8 grades |

71% |

75% |

76% |

|

(21) |

(65) |

(25) |

Grades 8-11 |

58% |

66% |

69% |

|

(97) |

(216) |

(48) |

Grade 12 |

46% |

54% |

62% |

|

(127) |

(217) |

(39) |

Some college |

51% |

44% |

71% |

|

(76) |

(108) |

(7) |

College |

29% |

46% |

100% |

|

(56) |

(56) |

(1) |

Some postgraduate study |

32% |

30% |

50% |

|

(25) |

(23) |

(2) |

Source: Robinson (1976)

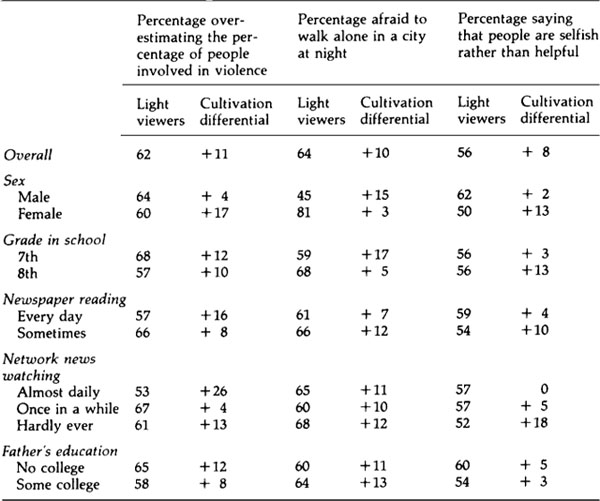

To test this diagnosis Robinson re-analysed data from a nationwide survey of American voters interviewed during the 1968 Presidential election campaign. The respondents were divided into three groups; those relying on media other than television for following political affairs; those relying primarily on television and those relying only on television for following politics. The extent of agreement with several statements expressing trust or mistrust in American political institutions was compared for members of each group. Table 3 presents an example of this work, based on responses to the statement: ‘Generally speaking, those we elect to Congress in Washington lose touch with the people pretty quickly’.

The top part of the Table does in fact show more mistrust among those relying on television to follow political affairs than among those who do not rely on television. The same pattern holds in the rest of the Table, where the data have been controlled for the educational level of the respondents. Such control is necessary, because the association of mistrust of politicians with dependence on television could have been due simply to the fact that the less educated respondents were both more prone to mistrust and heavy users of television. But the bottom part of the Table suggests that mistrust and dependence on television went together even when educational level was held constant.

On the face of it, this pattern seems clear and its interpretation straightforward. Nevertheless, its methodological foundations were attacked by Miller, Erbring and Goldenberg (1976) on two grounds. First, they asked, where is the crucial evidence demonstrating the negative and antiinstitutional quality of television news, which is supposedly productive of viewer mistrust? Without some analysis of the news content of television, they maintained, a vital link in the supposed chain of causation is missing. Second, they argued, subjective statements about reliance on a medium provide no measure of an individual's actual exposure to the medium or to that part of its contents that supposedly act as a trigger of mistrust. Controlling for educational level was also, according to these critics, insufficient to rule out the influence of other factors, since other studies have shown dependence on television to go with low levels of political information and interest, independently of levels of education, and those are characteristics that could be related to cynicism and mistrust. Then, as if to clinch these arguments, they examined the relationship between frequency of television news viewing and attitudes similar to those examined by Robinson, and reported little evidence of any effect.

These authors also presented some evidence of their own on the same subject, striving to apply their methodological prescriptions in practice. For this purpose, they looked at change over time, examining data taken from members of a national sample who had been interviewed first in 1972 and again in 1974 and who had on both occasions responded to five statements comprising a so-called trust in government scale. Within the sample, they compared the readers of two kinds of newspapers—whose front-page stories presented, as ascertained by content analysis, above-average and below-average amounts of criticism of politicians or political institutions—to see whether members of the former group displayed a bigger increase in mistrust of government. Their data suggested that mistrust had in fact increased over the two-year period throughout the American public—even among readers of relatively uncritical newspapers. They also found that the tide of increasing mistrust reached higher levels among those with lower levels of formal education. However, the growth of mistrust over time was greater among readers of critical papers than among readers of the uncritical ones. The differential widened considerably when the analysis was confined to frequent readers of the two sorts of newspapers. It looked as if frequent readers of the more critical papers were especially receptive to their papers’ critical outlook.

The authors concluded their analysis on the following note:

The political meaning of the relationship between newspaper criticism and political cynicism is not entirely obvious. Politics is conflict, and where conflict is involved negativism and criticism will surely exist. Newspaper stories that simply report disturbing events in a fairly objective style will presumably produce discontent. What we have found, however, goes beyond the impact of events and reflects the internal politics of newspapers. The relationships disclosed by the analysis are far too systematic to suggest that they simply reflect a happenstance of presentation style. Only systematic editorial influence could produce such a large variation in degree of criticism across papers. This does not imply only that some newspapers set out to be particularly critical—perhaps to fulfil their function as an adversary press. One must also assume that a systematic avoidance of criticism is occurring in other papers…. Whatever the explanation for the different levels of criticism in newspapers it is quite clear from the evidence that type-set politics have a substantial impact on public attitudes. (Miller et al., 1976)

Two further points are worth noting in connection with these examples. First, they illustrate that research on the political effects of the media need not be confined to the study of election campaigns and indeed can embrace questions other than the impact of the media on voting behaviour. Second, they suggest that the direction of media coverage of political affairs may have repercussions on political legitimacy. Media outlets in a given society may vary considerably in the amount of institutional support or criticism they project, and these may accelerate a growth of mistrust rather than invariably promote the legitimacy of political institutions. This last point stands in some conflict with the premise, shared by some Marxist analysts of the media, that support for the legitimacy of regimes is one of the main consequences of the operation of the media in capitalist societies.

Television and ‘the social construction of reality’

Everybody carries a set of more or less coherent images in his mind of the kind of society he inhabits: what it stands for; what its key institutions and power groups are like; the rules of social order that prevail; how values and rewards are allocated and to whom. Of course such impressions are partly formed by people's direct experiences of life. They also reflect their past and on-going involvement with society's traditional agencies of socialization and centres of ritual and myth—e.g. the family, schools, churches, sporting events, festive celebrations, patriotic ceremonies, etc. But one group of media researchers, George Gerbner and his colleagues at the Annenberg School of Communication in the University of Pennsylvania, maintain that television has become for many people a prime source of socially constructed reality which they define as ‘a coherent picture of what exists, what is important, how things are related and what is right’ (Gerbner et al, 1979, p. 179). Their work, the validity of which is hotly debated, is especially interesting for proposing a way to test the hypothesis that important political influences can stem from messages that in themselves are not in a narrow or conventional sense ‘political’.

The Gerbner thesis rests on four main assumptions (each of which is likely to be challenged by critics of this controversial point of view). One is that in modern society people are becoming more and more dependent on vicarious sources of experience: ‘the fabric of popular culture that relates elements of existence to each other and structures the common consciousness…is now largely a manufactured product’, purveyed through mass communications (Gerbner, 1972, p. 37). Second, it is alleged that television, a mass medium which penetrates all sectors of society, projects a view of the world through repetitive and pervasive patterns that are in themselves organically interrelated and internally consistent. Third, viewers tend to absorb the meanings embedded in this fabric, because they use the medium ‘largely non-selectively and by the clock rather than by the program’ (Gerbner, Gross, Signorielli, Morgan and Jackson-Beeck, 1979, p. 180). A fourth assumption points more directly to the way in which these ideas have so far mainly been tested. This is that ‘violence plays a key role in TV's portrayal of the social order’—an assumption, incidentally, which illustrates this group's concern with all forms of programme output and not just informational broadcasting.

The Annenberg research strategy depends on the fact that TV portrayals of social reality are in some respects distorted or exaggerated. Content analysis can show, for example, that characters in television drama are more likely to encounter personal violence than will the average man in the street, and that murder is a more common crime in programme plots (relative to other offences) than in real life. The Annenberg researchers have accordingly asked surveyed sample members to say which of two different statements about social violence is correct, one which is in line with official statistics and one which corresponds more closely to ‘television reality’. Their hypothesis is that heavy viewers of the medium will more often give the ‘television answer’ to such questions than will light viewers. In addition, they suppose that heavy viewers should draw certain conclusions from what they have seen about how to react to the world of violence. For example, they hypothesize that heavy viewers will more often admit to being afraid to walk alone in the city streets at night and will show more mistrust in their dealings with other people.

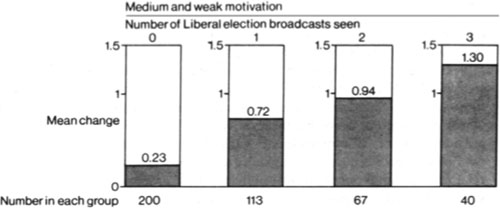

The findings reported by Gerbner et al. in a series of articles have usually confirmed their expectations. Table 4 shows how their results, taken in this case from a New Jersey sample of 447 7th-and 8th-grade school-children (aged 13–14) are usually presented. For each of three sets of data (concerning the prevalence of violence, the danger of urban strolls, and the trustworthiness of other people, respectively) the left-hand column shows the percentage of light TV viewers giving the ‘TV answer’. The difference between the responses of light viewers and of heavy TV viewers has been labelled by Gerbner and his colleagues a ‘cultivation differential’, meaning by this the difference supposedly made by television's ‘cultivation’ of a certain image of social reality. This difference is shown in the right-hand column. The table presents the results, not only for the sample as a whole, but also for a number of separate sub-groups within it, defined by such characteristics as sex, grade in school, father's educational level (signifying the family's socio-economic status) and media use habits. It can be seen that in this sample the heavy viewers, regardless of subgroup, almost always gave the supposed ‘television answer’ in higher proportion than did the light viewers. Heavy exposure to television, claim the researchers, indeed results in acceptance of the view of social reality projected by that medium.

Table 4: Heavy viewers of TV overestimate violence in society and find the world a mean place

Source: Adapted from: Gerbner et al. (1979)

Other scholars are sceptical about these findings. Although their consistency is impressive, the relationship between television viewing and perceptions of social reality that they imply is rather weaker than the Gerbner notion of the medium as a near-sovereign shaper of culture might have led one to expect. Exact definitions of what counts as a heavy or a light viewer are rarely given in the tables. The order of causation is also problematic. Heavy viewers may bring a more simplistic and wary view of the world to their experience of television instead of taking over that point of view from its programmes. So far, very few efforts have been made to chart the acquisition by heavy viewers of such social beliefs over a longer period of time in which the direction of causation could be more closely examined. Most striking is the failure of the Gerbner team to comment on, or to try to make sense of, the many differences between sample subgroups that their detailed results reveal. Why, say, should heavy viewing males be more afraid to walk alone at night than are equivalent women, when the reverse pattern applies to levels of personal mistrust?

Such neglect probably reflects the concern of Gerbner and his colleagues to demonstrate an overall effect of television exposure regardless of population differences. But that is why some critics see them as having naively reverted to ‘mass society’ notions that were discarded long ago by most other students of mass media effects. It is also the target of critics like Hawkins and Pingree (1980) who contend that differences both of individual psychology and in the forms of mass media content that audience members regularly consume must help to determine how people construct social reality and from what main sources. They argue that the influence of television on people's ideas about society should vary according to a number of intervening variables, including their information-processing ability; critical awareness of television; direct experience of other sources providing confirmation or disconfirmation of TV messages; social structural position; and patronage of various forms of programme content. Underlying all this, of course, there lurks a more profound philosophic difference. The Gerbner position tends to regard the mass media as capable of imposing categories through which reality is perceived, by-passing potential neutralizing factors and engulfing the audience in a new symbolic environment. By their critics, however, media influence is regarded as essentially differentiated, filtered through and refracted by the diverse backgrounds, cultures, group affiliations and life-styles of individual audience members. (Note: Since this chapter was written, Gerbner and his colleagues have tilted lances with Paul Hirsch in the pages of Communication Research. In the course of this debate Gerbner and his colleagues seem to have taken a more differentiated view of the ways in which television influences the viewers’ construction of social reality.)

CONCLUSION: TOWARD A CONVERGENCE OF CONCERN OVER AUDIENCE EFFECTS?

The reader of the first part of this chapter will have learned that empirical enquiry into the audience effects of mass communication is not a universally applauded pursuit. Numerous sources of doubt and criticism were identified there, but at the core of the debate was a polarization of outlook between pluralist and Marxist approaches to the analysis of mass communication systems and processes. We argued that different judgements about the scientific pay-off to be expected from effects studies followed logically from differences between pluralist and Marxist views of society and of the role of the mass media in society. One conclusion which might have been drawn from the discussion is that the gap between the two approaches is so wide as to be unbridgeable. Nevertheless, in this concluding section we wish to consider how abiding such a compartmentalization of outlook is likely to prove, and whether any signs can be discerned of the emergence of a measure of agreement between researchers of different persuasions about some of the issues involved in studying the impact of the mass media.

At the outset of this exploratory journey it should be firmly stated that no papering over of the ideological and theoretical incompatibilities of Marxism and pluralism is envisaged. Holders of the former position are bound to postulate a subordination of mass media institutions to the interests of dominant classes, just as scholars in the latter camp will conceive the media as reacting to and impinging on a wider and much more loosely-knit set of socio-political power groupings. It is not merely unrealistic to expect either side to abandon its theoretical core; such a move if it happened would also dilute what is one of the most exciting sources of significant debate in the field at the present time. Rather, the question for review is whether the two schools can converge in studying audience responses to mass communication so as to put their respective theories to an empirical test at that level.

It may be useful to summarize at this point the conceptual obstacles to that form of convergence. Preoccupation with the effects of the mass media follows naturally from the pluralist tradition's view of society as constituting a plurality of potential concentrations of power (albeit not necessarily equal to each other) which are engaged in a contest for ascendancy and dominance. The mass media are then seen as a central means through which this contest is conducted and public support for one or another grouping or point of view is mobilized. Clearly, questions about the effectiveness of the media as sources of influence and persuasion loom large in this perspective, and the attention of media researchers is thus directed to ways of measuring and assessing such influence and to the sociological and psychological variables that intervene in and filter the process of persuasion. The Marxist perspective, on the other hand, starts from Marx's familiar assertion that, The ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas of the epoch’, and so can readily relegate the question of media effects (if defined in terms of their capacity to bring about changes in attitudes and opinions) to near-irrelevance. The social functions of the mass media are conceptualized instead in terms of their ideological role in the production and reproduction of consensus, and the central questions raised focus on explaining how that role is performed and consensus is achieved.

Put in this manner, the differences appear basic. Nevertheless, in some recent work and writing on both sides of the theoretical/ideological divide it is possible to discern the seeds of a measure of agreement, so far as conceptualization of the impact of the media on audiences is concerned, and hence also about the need to study audience-level processes. Interestingly, the first main moves towards convergence of this kind have been taken by those who are actively engaged in empirical effects research. We shall try to illustrate these by briefly looking from this point of view at three alreadydescribed lines of work being currently pursued by effects researchers: studies of the agenda-setting function of the media; studies of mass media constructions of social reality; and examinations of the role of the media in influencing—and typically eroding—public trust in government. We shall then conclude by giving our reading of the evidence of the development of awareness among certain Marxist students of the media of a need to examine the reception of mass-communicated messages by audience members.

In considering recent work in the effects tradition we wish to highlight two emergent themes: (1) media effects are conceptualized primarily in terms of the shaping of the categories and frameworks through which audience members perceive socio-political reality; (2) the impact of the media in producing and communicating these frameworks is treated as rooted in characteristics of media organizations and of the professional practices which prevail in them, rather than in features of the persuasion process. Taken together, these themes tend to cast the media in an ideological role in form (though not necessarily in direction) not unlike that proposed by Marxist analysts.

The main thrust of agenda-setting research assigns to the mass media an ability to signal to their audiences what are the most important issues of the day, and so to construct an ‘agenda for society’. Thus, according to this thesis, while the media may not be able to tell people what to think, they may be effective in telling them what to think about. Such a conceptualization reflects a shift from preoccupation with attitude and opinion change in the earlier stages of media effects research towards a concentration on the contributions of the media to the formation of frameworks through which people regard political events and debates. Furthermore, the mass media are seen to perform this role, not by analysing and arguing the merits of different issues, but by the manner in which they select, highlight and assign greater prominence to some issues rather than to others. The setting of the political agenda is thus seen as an implicit outcome of production practices in the media rather than as the deliberate attempt to determine what the public should think. It is consequently at least partially ‘hidden’ from the audience and may even be ‘hidden’ from professionals involved in news production themselves, who prefer to think of themselves as passing news events on to the audience instead of shaping them up through the application of value judgements and constructed frameworks of perception. Read in this manner, agenda-setting research appears to converge towards the Marxist view that the ideological role of the mass media has structural roots, embedded in routines and practices of media production, which in turn may reflect interpretative frameworks dominant in society at a given time.