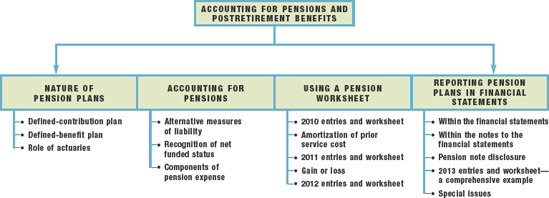

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

A pension plan is an arrangement whereby an employer provides benefits (payments) to retired employees for services they provided in their working years. Pension accounting may be divided and separately treated as accounting for the employer and accounting for the pension fund. The company or employer is the organization sponsoring the pension plan. It incurs the cost and makes contributions to the pension fund. The fund or plan is the entity that receives the contributions from the employer, administers the pension assets, and makes the benefit payments to the retired employees (pension recipients). Illustration 20-1 shows the three entities involved in a pension plan and indicates the flow of cash among them.

A pension plan is funded when the employer makes payments to a funding agency.[348] That agency accumulates the assets of the pension fund and makes payments to the recipients as the benefits come due.

Some pension plans are contributory. In these, the employees bear part of the cost of the stated benefits or voluntarily make payments to increase their benefits. Other plans are noncontributory. In these plans, the employer bears the entire cost. Companies generally design their pension plans so as to take advantage of federal income tax benefits. Plans that offer tax benefits are called qualified pension plans. They permit deductibility of the employer's contributions to the pension fund and tax-free status of earnings from pension fund assets.

The pension fund should be a separate legal and accounting entity. The pension fund, as a separate entity, maintains a set of books and prepares financial statements. Maintaining records and preparing financial statements for the fund, an activity known as "accounting for employee benefit plans," is not the subject of this chapter.[349] Instead, this chapter explains the pension accounting and reporting problems of the employer as the sponsor of a pension plan.

The need to properly administer and account for pension funds becomes apparent when you understand the size of these funds. Listed in Illustration 20-2 (on page 1051) are the pension fund assets and pension expenses of seven major companies.

As Illustration 20-2 indicates, pension expense is a substantial percentage of total pretax income for many companies.[350] The two most common types of pension plans are defined-contribution plans and defined-benefit plans, and we look at each of them in the following sections.

In a defined-contribution plan, the employer agrees to contribute to a pension trust a certain sum each period, based on a formula. This formula may consider such factors as age, length of employee service, employer's profits, and compensation level. The plan defines only the employer's contribution. It makes no promise regarding the ultimate benefits paid out to the employees. A common form of this plan is a 401(k) plan.

The size of the pension benefits that the employee finally collects under the plan depends on several factors: the amounts originally contributed to the pension trust, the income accumulated in the trust, and the treatment of forfeitures of funds caused by early terminations of other employees. A company usually turns over to an independent third-party trustee the amounts originally contributed. The trustee, acting on behalf of the beneficiaries (the participating employees), assumes ownership of the pension assets and is accountable for their investment and distribution. The trust is separate and distinct from the employer.

The accounting for a defined-contribution plan is straightforward. The employee gets the benefit of gain (or the risk of loss) from the assets contributed to the pension plan. The employer simply contributes each year based on the formula established in the plan. As a result, the employer's annual cost (pension expense) is simply the amount that it is obligated to contribute to the pension trust. The employer reports a liability on its balance sheet only if it does not make the contribution in full. The employer reports an asset only if it contributes more than the required amount.

In addition to pension expense, the employer must disclose the following for a defined-contribution plan: a plan description, including employee groups covered; the basis for determining contributions; and the nature and effect of significant matters affecting comparability from period to period. [2]

A defined-benefit plan outlines the benefits that employees will receive when they retire. These benefits typically are a function of an employee's years of service and of the compensation level in the years approaching retirement.

To meet the defined-benefit commitments that will arise at retirement, a company must determine what the contribution should be today (a time value of money computation). Companies may use many different contribution approaches. However, the funding method should provide enough money at retirement to meet the benefits defined by the plan.

The employees are the beneficiaries of a defined-contribution trust, but the employer is the beneficiary of a defined-benefit trust. Under a defined-benefit plan, the trust's primary purpose is to safeguard and invest assets so that there will be enough to pay the employer's obligation to the employees. In form, the trust is a separate entity. In substance, the trust assets and liabilities belong to the employer. That is, as long as the plan continues, the employer is responsible for the payment of the defined benefits (without regard to what happens in the trust). The employer must make up any shortfall in the accumulated assets held by the trust. On the other hand, the employer can recapture any excess accumulated in the trust, either through reduced future funding or through a reversion of funds.

Because a defined-benefit plan specifies benefits in terms of uncertain future variables, a company must establish an appropriate funding pattern to ensure the availability of funds at retirement in order to provide the benefits promised. This funding level depends on a number of factors such as turnover, mortality, length of employee service, compensation levels, and interest earnings.

Employers are at risk with defined-benefit plans because they must contribute enough to meet the cost of benefits that the plan defines. The expense recognized each period is not necessarily equal to the cash contribution. Similarly, the liability is controversial because its measurement and recognition relate to unknown future variables. Thus, the accounting issues related to this type of plan are complex. Our discussion in the following sections deals primarily with defined-benefit plans.[351]

Defined-contribution plans have become much more popular with employers than defined-benefit plans. One reason is that they are cheaper. Defined-contribution plans often cost no more than 3 percent of payroll, whereas defined-benefit plans can cost 5 to 6 percent of payroll.

In the late 1970s approximately 15 million individuals had defined-contribution plans; today over 62 million do. The following chart reflects this significant change. It shows the percentage of companies using various types of plans, based on a survey of approximately 150 CFOs and managing corporate directors.

Although many companies are changing to defined-contribution plans, over 40 million individuals still are covered under defined-benefit plans.

The problems associated with pension plans involve complicated mathematical considerations. Therefore, companies engage actuaries to ensure that a pension plan is appropriate for the employee group covered.[352] Actuaries are individuals trained through a long and rigorous certification program to assign probabilities to future events and their financial effects. The insurance industry employs actuaries to assess risks and to advise on the setting of premiums and other aspects of insurance policies. Employers rely heavily on actuaries for assistance in developing, implementing, and funding pension funds.

Actuaries make predictions (called actuarial assumptions) of mortality rates, employee turnover, interest and earnings rates, early retirement frequency, future salaries, and any other factors necessary to operate a pension plan. They also compute the various pension measures that affect the financial statements, such as the pension obligation, the annual cost of servicing the plan, and the cost of amendments to the plan. In summary, accounting for defined-benefit pension plans relies heavily upon information and measurements provided by actuaries.

In accounting for a company's pension plan, two questions arise: (1) What is the pension obligation that a company should report in the financial statements? (2) What is the pension expense for the period? Attempting to answer the first question has produced much controversy.

Most agree that an employer's pension obligation is the deferred compensation obligation it has to its employees for their service under the terms of the pension plan. Measuring that obligation is not so simple, though, because there are alternative ways of measuring it.[353]

One measure of the pension obligation is to base it only on the benefits vested to the employees. Vested benefits are those that the employee is entitled to receive even if he or she renders no additional services to the company. Most pension plans require a certain minimum number of years of service to the employer before an employee achieves vested benefits status. Companies compute the vested benefit obligation using only vested benefits, at current salary levels.

Another way to measure the obligation uses both vested and nonvested years of service. On this basis, the company computes the deferred compensation amount on all years of employees' service—both vested and nonvested—using current salary levels. This measurement of the pension obligation is called the accumulated benefit obligation.

A third measure bases the deferred compensation amount on both vested and non-vested service using future salaries. This measurement of the pension obligation is called the projected benefit obligation. Because future salaries are expected to be higher than current salaries, this approach results in the largest measurement of the pension obligation.

The choice between these measures is critical. The choice affects the amount of a company's pension liability and the annual pension expense reported. The diagram in Illustration 20-3 presents the differences in these three measurements.

Which of these alternative measures of the pension liability does the profession favor? The profession adopted the projected benefit obligation—the present value of vested and nonvested benefits accrued to date, based on employees' future salary levels.[354] Those in favor of the projected benefit obligation contend that a promise by an employer to pay benefits based on a percentage of the employees' future salaries is far greater than a promise to pay a percentage of their current salary, and such a difference should be reflected in the pension liability and pension expense.

Moreover, companies discount to present value the estimated future benefits to be paid. Minor changes in the interest rate used to discount pension benefits can dramatically affect the measurement of the employer's obligation. For example, a 1 percent decrease in the discount rate can increase pension liabilities 15 percent. Accounting rules require that, at each measurement date, a company must determine the appropriate discount rate used to measure the pension liability, based on current interest rates.

Companies must recognize on their balance sheet the full overfunded or under-funded status of their defined-benefit pension plan.[355] [3] The overfunded or underfunded status is measured as the difference between the fair value of the plan assets and the projected benefit obligation.

To illustrate, assume that Coker Company has a projected benefit obligation of $300,000, and the fair value of its plan assets is $210,000. In this case, Coker Company's pension plan is underfunded, and therefore it reports a pension liability of $90,000 ($300,000 − $210,000) on its balance sheet. If, instead, the fair value of Coker's plan assets were $430,000, it would report a pension asset of $130,000 ($430,000 − $300,000).

As recently as 2004, pension plans for companies in the S&P 500 were underfunded (liabilities exceeded assets) in the aggregate by $158.4 billion. In 2007, by slowing the growth of pension liabilities and increasing contributions to pension funds, the S&P 500 companies reported aggregate overfunding (assets exceeded liabilities) of $61.9 billion.[356]

There is broad agreement that companies should account for pension cost on the accrual basis.[357] The profession recognizes that accounting for pension plans requires measurement of the cost and its identification with the appropriate time periods. The determination of pension cost, however, is extremely complicated because it is a function of the following components.

Service Cost. Service cost is the expense caused by the increase in pension benefits payable (the projected benefit obligation) to employees because of their services rendered during the current year. Actuaries compute service cost as the present value of the new benefits earned by employees during the year.

Interest on the Liability. Because a pension is a deferred compensation arrangement, there is a time value of money factor. As a result, companies record the pension liability on a discounted basis. Interest expense accrues each year on the projected benefit obligation just as it does on any discounted debt. The actuary helps to select the interest rate, referred to as the settlement rate.

Actual Return on Plan Assets. The return earned by the accumulated pension fund assets in a particular year is relevant in measuring the net cost to the employer of sponsoring an employee pension plan. Therefore, a company should adjust annual pension expense for interest and dividends that accumulate within the fund, as well as increases and decreases in the market value of the fund assets.

Amortization of Prior Service Cost. Pension plan amendments (including initiation of a pension plan) often include provisions to increase benefits (or in rare situations, to decrease benefits) for employee service provided in prior years. A company grants plan amendments with the expectation that it will realize economic benefits in future periods. Thus, it allocates the cost (prior service cost) of providing these retroactive benefits to pension expense in the future, specifically to the remaining service-years of the affected employees.

Gain or Loss. Volatility in pension expense can result from sudden and large changes in the market value of plan assets and by changes in the projected benefit obligation (which changes when actuaries modify assumptions or when actual experience differs from expected experience). Two items comprise this gain or loss: (1) the difference between the actual return and the expected return on plan assets, and (2) amortization of the net gain or loss from previous periods. We will discuss this complex computation later in the chapter.

Illustration 20-4 shows the components of pension expense and their effect on total pension expense (increase or decrease).

The service cost is the actuarial present value of benefits attributed by the pension benefit formula to employee service during the period. That is, the actuary predicts the additional benefits that an employer must pay under the plan's benefit formula as a result of the employees' current year's service, and then discounts the cost of those future benefits back to their present value.

The Board concluded that companies must consider future compensation levels in measuring the present obligation and periodic pension expense if the plan benefit formula incorporates them. In other words, the present obligation resulting from a promise to pay a benefit of 1 percent of an employee's final pay differs from the promise to pay 1 percent of current pay. To overlook this fact is to ignore an important aspect of pension expense. Thus, the FASB adopts the benefits/years-of-service actuarial method, which determines pension expense based on future salary levels.

Some object to this determination, arguing that a company should have more freedom to select an expense recognition pattern. Others believe that incorporating future salary increases into current pension expense is accounting for events that have not yet happened. They argue that if a company terminates the plan today, it pays only liabilities for accumulated benefits. Nevertheless, the FASB indicates that the projected benefit obligation provides a more realistic measure of the employer's obligation under the plan on a going concern basis and, therefore, companies should use it as the basis for determining service cost.

The second component of pension expense is interest on the liability, or interest expense. Because a company defers paying the liability until maturity, the company records it on a discounted basis. The liability then accrues interest over the life of the employee. The interest component is the interest for the period on the projected benefit obligation outstanding during the period. The FASB did not address the question of how often to compound the interest cost. To simplify our illustrations and problem materials, we use a simple-interest computation, applying it to the beginning-of-the-year balance of the projected benefit liability.

How do companies determine the interest rate to apply to the pension liability? The Board states that the assumed discount rate should reflect the rates at which companies can effectively settle pension benefits. In determining these settlement rates, companies should look to rates of return on high-quality fixed-income investments currently available, whose cash flows match the timing and amount of the expected benefit payments. The objective of selecting the assumed discount rates is to measure a single amount that, if invested in a portfolio of high-quality debt instruments, would provide the necessary future cash flows to pay the pension benefits when due.

Pension plan assets are usually investments in stocks, bonds, other securities, and real estate that a company holds to earn a reasonable return, generally at minimum risk. Employer contributions and actual returns on pension plan assets increase pension plan assets. Benefits paid to retired employees decrease them. As we indicated, the actual return earned on these assets increases the fund balance and correspondingly reduces the employer's net cost of providing employees' pension benefits. That is, the higher the actual return on the pension plan assets, the less the employer has to contribute eventually and, therefore, the less pension expense that it needs to report.

The actual return on the plan assets is the increase in pension funds from interest, dividends, and realized and unrealized changes in the fair-market value of the plan assets. Companies compute the actual return by adjusting the change in the plan assets for the effects of contributions during the year and benefits paid out during the year. The equation in Illustration 20-5, or a variation thereof, can be used to compute the actual return.

Stated another way, the actual return on plan assets is the difference between the fair value of the plan assets at the beginning of the period and at the end of the period, adjusted for contributions and benefit payments. Illustration 20-6 uses the equation above to compute the actual return, using some assumed amounts.

If the actual return on the plan assets is positive (a gain) during the period, a company subtracts it when computing pension expense. If the actual return is negative (a loss) during the period, the company adds it when computing pension expense.[358]

We will now illustrate the basic computation of pension expense using the first three components: (1) service cost, (2) interest on the liability, and (3) actual return on plan assets. We discuss the other pension-expense components (amortization of prior service cost, and gains and losses) in later sections.

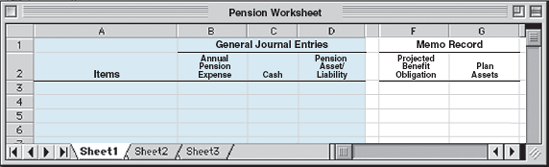

Companies often use a worksheet to record pension-related information. As its name suggests, the worksheet is a working tool. A worksheet is not a permanent accounting record: it is neither a journal nor part of the general ledger. The work-sheet is merely a device to make it easier to prepare entries and the financial statements.[359] Illustration 20-7 shows the format of the pension worksheet.

The "General Journal Entries" columns of the worksheet (near the left side) determine the entries to record in the formal general ledger accounts. The "Memo Record" columns (on the right side) maintain balances in the projected benefit obligation and the plan assets. The difference between the projected benefit obligation and the fair value of the plan assets is the pension asset/liability, which is shown in the balance sheet. If the projected benefit obligation is greater than the plan assets, a pension liability occurs. If the projected benefit obligation is less than the plan assets, a pension asset occurs.

On the first line of the worksheet, a company records the beginning balances (if any). It then records subsequent transactions and events related to the pension plan using debits and credits, using both sets of columns as if they were one. For each transaction or event, the debits must equal the credits. The ending balance in the Pension Asset/Liability column should equal the net balance in the memo record.

To illustrate the use of a worksheet and how it helps in accounting for a pension plan, assume that on January 1, 2010, Zarle Company provides the following information related to its pension plan for the year 2010.

Plan assets, January 1, 2010, are $100,000.

Projected benefit obligation, January 1, 2010, is $100,000.

Annual service cost is $9,000.

Settlement rate is 10 percent.

Actual return on plan assets is $10,000.

Funding contributions are $8,000.

Benefits paid to retirees during the year are $7,000.

Using the data presented on page 1058, the worksheet in Illustration 20-8 presents the beginning balances and all of the pension entries recorded by Zarle in 2010. Zarle records the beginning balances for the projected benefit obligation and the pension plan assets on the first line of the worksheet in the memo record. Because the projected benefit obligation and the plan assets are the same at January 1, 2010, the Pension Asset/Liability account has a zero balance at January 1, 2010.

Entry (a) in Illustration 20-8 records the service cost component, which increases pension expense by $9,000 and increases the liability (projected benefit obligation) by $9,000. Entry (b) accrues the interest expense component, which increases both the liability and the pension expense by $10,000 (the beginning projected benefit obligation multiplied by the settlement rate of 10 percent). Entry (c) records the actual return on the plan assets, which increases the plan assets and decreases the pension expense. Entry (d) records Zarle's contribution (funding) of assets to the pension fund, thereby decreasing cash by $8,000 and increasing plan assets by $8,000. Entry (e) records the benefit payments made to retirees, which results in equal $7,000 decreases to the plan assets and the projected benefit obligation.

Zarle makes the "formal journal entry" on December 31, which records the pension expense in 2010, as follows.

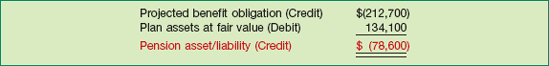

The credit to Pension Asset/Liability for $1,000 represents the difference between the 2010 pension expense of $9,000 and the amount funded of $8,000. Pension Asset/ Liability (credit) is a liability because Zarle underfunds the plan by $1,000. The Pension Asset/Liability account balance of $1,000 also equals the net of the balances in the memo accounts. Illustration 20-9 shows that the projected benefit obligation exceeds the plan assets by $1,000, which reconciles to the pension liability reported in the balance sheet.

If the net of the memo record balances is a credit, the reconciling amount in the pension asset/liability column will be a credit equal in amount. If the net of the memo record balances is a debit, the pension asset/liability amount will be a debit equal in amount. The worksheet is designed to produce this reconciling feature, which is useful later in the preparation of the financial statements and required note disclosure related to pensions.

In this illustration (for 2010), the debit to Pension Expense exceeds the credit to Cash, resulting in a credit to Pension Asset/Liability—the recognition of a liability. If the credit to Cash exceeded the debit to Pension Expense, Zarle would debit Pension Asset/Liability—the recognition of an asset.

When either initiating (adopting) or amending a defined-benefit plan, a company often provides benefits to employees for years of service before the date of initiation or amendment. As a result of this prior service cost, the projected benefit obligation is increased to recognize this additional liability. In many cases, the increase in the projected benefit obligation is substantial.

Should a company report an expense for these prior service costs (PSC) at the time it initiates or amends a plan? The FASB says no. The Board's rationale is that the employer would not provide credit for past years of service unless it expects to receive benefits in the future. As a result, a company should not recognize the retroactive benefits as pension expense in the year of amendment. Instead, the employer initially records the prior service cost as an adjustment to other comprehensive income. The employer then recognizes the prior service cost as a component of pension expense over the remaining service lives of the employees who are expected to benefit from the change in the plan.

The cost of the retroactive benefits (including any benefits provided to existing retirees) is the increase in the projected benefit obligation at the date of the amendment. An actuary computes the amount of the prior service cost. Amortization of the prior service cost is also an accounting function performed with the assistance of an actuary.

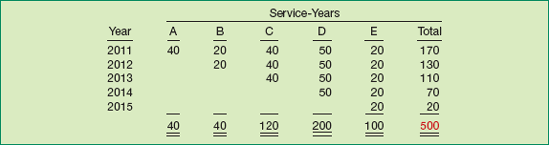

The Board prefers a years-of-service method that is similar to a units-of-production computation. First, the company computes the total number of service-years to be worked by all of the participating employees. Second, it divides the prior service cost by the total number of service-years, to obtain a cost per service-year (the unit cost). Third, the company multiplies the number of service-years consumed each year by the cost per service-year, to obtain the annual amortization charge.

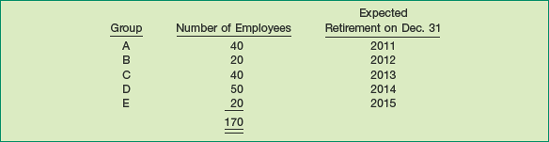

To illustrate the amortization of the prior service cost under the years-of-service method, assume that Zarle Company's defined-benefit pension plan covers 170 employees. In its negotiations with the employees, Zarle Company amends its pension plan on January 1, 2011, and grants $80,000 of prior service costs to its employees. The employees are grouped according to expected years of retirement, as shown below.

Illustration 20-10 shows computation of the service-years per year and the total service-years.

Computed on the basis of a prior service cost of $80,000 and a total of 500 service-years for all years, the cost per service-year is $160 ($80,000 ÷ 500). The annual amount of amortization based on a $160 cost per service-year is computed as follows.

An alternative method of computing amortization of prior service cost is permitted: Employers may use straight-line amortization over the average remaining service life of the employees. In this case, with 500 service-years and 170 employees, the average would be 2.94 years (500 ÷ 170). The annual expense would be $27,211 ($80,000 ÷ 2.94). Using this method, Zarle Company would charge cost to expense in 2011, 2012, and 2013 as follows.

Continuing the Zarle Company illustration into 2011, we note that the company amends the pension plan on January 1, 2011, to grant employees prior service benefits with a present value of $80,000. Zarle uses the annual amortization amounts, as computed in the previous section using the years-of-service approach ($27,200 for 2011). The following additional facts apply to the pension plan for the year 2011.

Annual service cost is $9,500.

Settlement rate is 10 percent.

Actual return on plan assets is $11,100.

Annual funding contributions are $20,000.

Benefits paid to retirees during the year are $8,000.

Amortization of prior service cost (PSC) using the years-of-service method is $27,200. Accumulated other comprehensive income (hereafter referred to as accumulated OCI) on December 31, 2010, is zero.

Illustration 20-12 presents a worksheet of all the pension entries and information recorded by Zarle in 2011. We now add an additional column to the worksheet to record the prior service cost adjustment to other comprehensive income. In addition, as shown in the last two lines of the "Items" column, the other comprehensive income amount related to prior service cost is added to accumulated other comprehensive income ("Accumulated OCI") to arrive at a debit balance of $52,800 at December 31, 2011.

The first line of the worksheet shows the beginning balances of the Pension Asset/Liability account and the memo accounts. Entry (f) records Zarle's granting of prior service cost, by adding $80,000 to the projected benefit obligation and decreasing other comprehensive income—prior service cost by the same amount. Entries (g), (h), (i), (k), and (l) are similar to the corresponding entries in 2010. To compute the interest cost on the projected benefit obligation for entry (h), we use the beginning projected benefit balance of $192,000, which has been adjusted for the prior service cost amendment on January 1, 2011. Entry (j) records the 2011 amortization of prior service cost by debiting Pension Expense for $27,200 and crediting Other Comprehensive Income (PSC) for the same amount.

Zarle makes the following journal entry on December 31 to formally record the 2011 pension expense (the sum of the annual pension expense column), and related pension information.

Because the debits to Pension Expense and to Other Comprehensive Income (PSC) exceed the funding, Zarle credits the Pension Asset/Liability account for the $77,600 difference. That account is a liability. In 2011, as in 2010, the balance of the Pension Asset/Liability account ($78,600) is equal to the net of the balances in the memo accounts, as shown in Illustration 20-13.

The reconciliation is the formula that makes the worksheet work. It relates the components of pension accounting, recorded and unrecorded, to one another.

Of great concern to companies that have pension plans are the uncontrollable and unexpected swings in pension expense that can result from (1) sudden and large changes in the market value of plan assets, and (2) changes in actuarial assumptions that affect the amount of the projected benefit obligation. If these gains or losses impact fully the financial statements in the period of realization or incur-rence, substantial fluctuations in pension expense result.

Therefore, the FASB decided to reduce the volatility associated with pension expense by using smoothing techniques that dampen and in some cases fully eliminate the fluctuations.

One component of pension expense, actual return on plan assets, reduces pension expense (assuming the actual return is positive). A large change in the actual return can substantially affect pension expense for a year. Assume a company has a 40 percent return in the stock market for the year. Should this substantial, and perhaps one-time, event affect current pension expense?

Actuaries ignore current fluctuations when they develop a funding pattern to pay expected benefits in the future. They develop an expected rate of return and multiply it by an asset value weighted over a reasonable period of time to arrive at an expected return on plan assets. They then use this return to determine a company's funding pattern.

The FASB adopted the actuary's approach to dampen wide swings that might occur in the actual return. That is, a company includes the expected return on the plan assets as a component of pension expense, not the actual return in a given year. To achieve this goal, the company multiplies the expected rate of return by the market-related value of the plan assets. The market-related asset value of the plan assets is either the fair value of plan assets or a calculated value that recognizes changes in fair value in a systematic and rational manner. [4][360]

The difference between the expected return and the actual return is referred to as the unexpected gain or loss; the FASB uses the term asset gains and losses. Asset gains occur when actual return exceeds expected return; asset losses occur when actual return is less than expected return.

What happens to unexpected gains or losses in the accounting for pensions? Companies record asset gains and asset losses in an account, Other Comprehensive Income (G/L), combining them with gains and losses accumulated in prior years. This treatment is similar to prior service cost. The Board believes this treatment is consistent with the practice of including in other comprehensive income certain changes in value that have not been recognized in net income (for example, unrealized gains and losses on available-for-sale securities). [5] In addition, the accounting is simple, transparent, and symmetrical.

To illustrate the computation of an unexpected gain or loss and its related accounting, assume that in 2012, Zarle Company has an actual return on plan assets of $12,000 when the expected return is $13,410 (the expected rate of return of 10% on plan assets times the beginning of the year plan assets). The unexpected asset loss of $1,410 ($12,000 − $13,410) is debited to Other Comprehensive Income (G/L) and credited to Pension Expense.

For some companies, pension plans generated real profits in the late 1990s. The plans not only paid for themselves but also increased earnings. This happens when the expected return on pension assets exceed the company's annual costs. At Norfolk Southern, pension income amounted to 12 percent of operating profit. It tallied 11 percent of operating profit at Lucent Technologies, Coastal Corp., and Unisys Corp. The issue is important because in these cases management is not driving the operating income—pension income is. And as a result, income can change quickly.

Unfortunately, when the stock market stops booming, pension expense substantially increases for many companies. The reason: Expected return on a smaller asset base no longer offsets pension service costs and interest on the projected benefit obligation. As a result, many companies find it difficult to meet their earnings targets, and at a time when meeting such targets is crucial to maintaining the stock price.

In estimating the projected benefit obligation (the liability), actuaries make assumptions about such items as mortality rate, retirement rate, turnover rate, disability rate, and salary amounts. Any change in these actuarial assumptions affects the amount of the projected benefit obligation. Seldom does actual experience coincide exactly with actuarial predictions. These unexpected gains or losses from changes in the projected benefit obligation are called liability gains and losses.

Companies report liability gains (resulting from unexpected decreases in the liability balance) and liability losses (resulting from unexpected increases) in Other Comprehensive Income (G/L). Companies combine the liability gains and losses in the same Other Comprehensive Income (G/L) account used for asset gains and losses. They accumulate the asset and liability gains and losses from year to year that are not amortized in Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income. This amount is reported on the balance sheet in the stockholders' equity section.

The asset gains and losses and the liability gains and losses can offset each other. As a result, the Accumulated OCI account related to gains and losses may not grow very large. But, it is possible that no offsetting will occur and that the balance in the Accumulated OCI account related to gains and losses will continue to grow.

To limit the growth of the Accumulated OCI account, the FASB invented the corridor approach for amortizing the account's accumulated balance when it gets too large. How large is too large? The FASB set a limit of 10 percent of the larger of the beginning balances of the projected benefit obligation or the market-related value of the plan assets. Above that size, the Accumulated OCI account related to gains and losses is considered too large and must be amortized.

To illustrate the corridor approach, data for Callaway Co.'s projected benefit obligation and plan assets over a period of six years are shown in Illustration 20-14.

How the corridor works becomes apparent when we portray the data graphically, as in Illustration 20-15.

If the balance in the Accumulated OCI account related to gains and losses stays within the upper and lower limits of the corridor, no amortization is required. In that case, Callaway carries forward unchanged the accumulated OCI related to gains and losses.

If amortization is required, the minimum amortization is the excess divided by the average remaining service period of active employees who are expected to receive benefits under the plan. Callaway may use any systematic method of amortization of gains and losses in lieu of the minimum, provided it is greater than the minimum. It must use the method consistently for both gains and losses, and must disclose the amortization method used.

In applying the corridor, companies should include amortization of the net gain or loss as a component of pension expense only if, at the beginning of the year, the net gain or loss in Accumulated OCI exceeded the corridor. That is, if no net gain or loss exists in Accumulated OCI at the beginning of the period, the company cannot recognize pension expense gains or losses in that period.

To illustrate the amortization of net gains and losses, assume the following information for Soft-White, Inc.

Soft-White recorded in Other Comprehensive Income actuarial losses of $400,000 in 2010 and $300,000 in 2011.

If the average remaining service life of all active employees is 5.5 years, the schedule to amortize the net gain or loss is as shown in Illustration 20-16.

As Illustration 20-16 indicates, the loss recognized in 2011 increased pension expense by $21,818. This amount is small in comparison with the total loss of $400,000. It indicates that the corridor approach dampens the effects (reduces volatility) of these gains and losses on pension expense.

The rationale for the corridor is that gains and losses result from refinements in estimates as well as real changes in economic value; over time, some of these gains and losses will offset one another. It therefore seems reasonable that Soft-White should not fully recognize gains and losses as a component of pension expense in the period in which they arise.

However, Soft-White should immediately recognize in net income certain gains and losses—if they arise from a single occurrence not directly related to the operation of the pension plan and not in the ordinary course of the employer's business. For example, a gain or loss that is directly related to a plant closing, a disposal of a business component, or a similar event that greatly affects the size of the employee work force, should be recognized as a part of the gain or loss associated with that event.

For example, at one time, Bethlehem Steel reported a quartererly loss of $477 million. A great deal of this loss was attributable to future estimated benefits payable to workers who were permanently laid off. In this situation, the loss should be treated as an adjustment to the gain or loss on the plant closing and should not affect pension cost for the current or future periods.

The difference between the actual return on plan assets and the expected return on plan assets is the unexpected asset gain or loss component. This component defers the difference between the actual return and expected return on plan assets in computing current-year pension expense. Thus, after considering this component, it is really the expected return on plan assets (not the actual return) that determines current pension expense.

Companies determine the amortized net gain or loss by amortizing the Accumulated OCI amount related to net gain or loss at the beginning of the year subject to the corridor limitation. In other words, if the accumulated gain or loss is greater than the corridor, these net gains and losses are subject to amortization. Soft-White computed this minimum amortization by dividing the net gains or losses subject to amortization by the average remaining service period. When the current-year unexpected gain or loss is combined with the amortized net gain or loss, we determine the current-year gain or loss. Illustration 20-17 summarizes these gain and loss computations.

In essence, these gains and losses are subject to triple smoothing. That is, companies first smooth the asset gain or loss by using the expected return. Second, they do not amortize the accumulated gain or loss at the beginning of the year unless it is greater than the corridor. Finally, they spread the excess over the remaining service life of existing employees.

Continuing the Zarle Company illustration, the following facts apply to the pension plan for 2012.

Annual service cost is $13,000.

Settlement rate is 10 percent; expected earnings rate is 10 percent.

Actual return on plan assets is $12,000.

Amortization of prior service cost (PSC) is $20,800.

Annual funding contributions are $24,000.

Benefits paid to retirees during the year are $10,500.

Changes in actuarial assumptions resulted in an end-of-year projected benefit obligation of $265,000.

The worksheet in Illustration 20-18 (on page 1068) presents all of Zarle's 2012 pension entries and related information. The first line of the worksheet records the beginning balances that relate to the pension plan. In this case, Zarle's beginning balances are the ending balances from its 2011 pension worksheet in Illustration 20-12 (page 1062).

Entries (m), (n), (o), (q), (r), and (s) are similar to the corresponding entries in 2010 or 2011.

Entries (o) and (p) are related. We explained the recording of the actual return in entry (o) in both 2010 and 2011; it is recorded similarly in 2012. In both 2010 and 2011 Zarle assumed that the actual return on plan assets was equal to the expected return on plan assets. In 2012, the expected return of $13,410 (the expected rate of return of 10 percent times the beginning-of-the-year plan assets balance of $134,100) is higher than the actual return of $12,000. To smooth pension expense, Zarle defers the unexpected loss of $1,410 ($13,410 − $12,000) by debiting the Other Comprehensive Income (G/L) account and crediting Pension Expense. As a result of this adjustment, the expected return on the plan assets is the amount actually used to compute pension expense.

Entry (t) records the change in the projected benefit obligation resulting from the change in the actuarial assumptions. As indicated, the actuary has now computed the ending balance to be $265,000. Given the PBO balance at December 31, 2011, and the related transactions during 2012, the PBO balance to date is computed as shown in Illustration 20-19.

The difference between the ending balance of $265,000 and the balance of $236,470 before the liability increase is $28,530 ($265,000 − $236,470). This $28,530 increase in the employer's liability is an unexpected loss. The journal entry on December 31, 2012, to record the pension information is as follows.

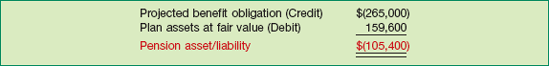

As the 2012 worksheet indicates, the $105,400 balance in the Pension Asset/Liability account at December 31, 2012, is equal to the net of the balances in the memo accounts. Illustration 20-20 shows this computation.

The chart below shows what has happened to the financial health of pension plans over the last few years. It is a real roller coaster.

At the turn of the century, when the stock market was strong, pension plans were overfunded. However the bubble burst, and by 2002 companies in the S&P 500 saw their pension plans funded at just 85 percent of reported liabilities. In recent years, plans have bounced back, and by 2007 pension plans were overfunded again. However, due to recent downturns, plans may be soon under-funded again.

A number of factors cause a fund to change from being overfunded to underfunded: First, low interest rates, such as those experienced in the early part of this decade, decimate returns on pension plan assets. As a result, pension fund assets have not grown; in some cases, they have declined in value. Second, using low interest rates to discount the projected benefit payments leads to a higher pension liability. Finally, more individuals are retiring, which leads to a depletion of the pension plan assets. In short, the years 2002 and 2003 produced the perfect pension storm. Since 2003, companies have increased contributions to their plans and curtailed benefits promised to employees, which have helped the plans bounce back.

Sources: David Zion and Bill Carcache, "The Magical World of Pensions: An Update," CSFB Equity Research: Accounting (September 8, 2004); and J. Ciesielski, "Benefit Plans 2007: Close To The Edge—And Back," The Analyst's Accounting Observer (April 25, 2008).

As you might suspect, a phenomenon as significant and complex as pensions involves extensive reporting and disclosure requirements. We will cover these requirements in two categories: (1) those within the financial statements, and (2) those within the notes to the financial statements.

Companies must recognize on their balance sheet the overfunded (pension asset) or underfunded (pension liability) status of their defined-benefit pension plan. The over-funded or underfunded status is measured as the difference between the fair value of the plan assets and the projected benefit obligation.

No portion of a pension asset is reported as a current asset. The excess of the fair value of the plan assets over the benefit obligation is classified as a noncurrent asset. The rationale for noncurrent classification is that the pension plan assets are restricted. That is, these assets are used to fund the projected benefit obligation, and therefore noncur-rent classification is appropriate.

The current portion of a net pension liability represents the amount of benefit payments to be paid in the next 12 months (or operating cycle, if longer), if that amount cannot be funded from existing plan assets. Otherwise, the pension liability is classified as a noncurrent liability.[361]

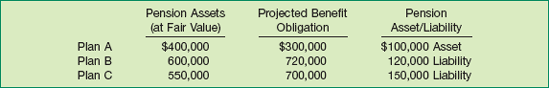

Some companies have two or more pension plans. In such instances, a question arises as to whether these multiple plans should be combined and shown as one amount on the balance sheet. The Board takes the position that all overfunded plans should be combined and shown as a pension asset on the balance sheet. Similarly, if the company has two or more underfunded plans, the underfunded plans are combined and shown as one amount on the balance sheet.

The FASB rejected the alternative of combining all plans and representing the net amount as a single net asset or net liability. The rationale: A company does not have the ability to offset excess assets of one plan against underfunded obligations of another plan. Furthermore, netting all plans is inappropriate because offsetting assets and liabilities is not permitted under GAAP unless a right of offset exists.

To illustrate, assume that Cresci Company has three pension plans as shown in Illustration 20-21.

In this case, Cresci reports a pension plan asset of $100,000 and a pension plan liability of $270,000 ($120,000 + $150,000).

Actuarial gains and losses not recognized as part of pension expense are recognized as increases and decreases in other comprehensive income. The same type of accounting is also used for prior service cost. The Board requires that the prior service cost arising in the year of the amendment (which increases the projected benefit obligation) be recognized by an offsetting debit to other comprehensive income. By recognizing both actuarial gains and losses and prior service cost as part of other comprehensive income, the Board believes that the usefulness of financial statements is enhanced.

To illustrate the presentation of other comprehensive income and related accumulated OCI, assume that Obey Company provides the following information for the year 2010. None of the Accumulated OCI on January 1, 2010, should be amortized in 2010.

Both the actuarial liability loss and the prior service adjustment decrease the funded status of the plan on the balance sheet. This results because the projected benefit obligation increases. However, neither the actuarial liability loss nor the prior service cost adjustment affects pension expense in 2010. In subsequent periods, these items will impact pension expense through amortization.

For Obey Company, the computation of "Other comprehensive loss" for 2010 is as follows.

The computation of "Comprehensive income" for 2010 is as follows.

The components of other comprehensive income must be reported in one of three ways: (1) in a second income statement, (2) in a combined statement of comprehensive income, or (3) as a part of the statement of stockholders' equity. Regardless of the format used, net income must be added to other comprehensive income to arrive at comprehensive income. For homework purposes, use the second income statement approach unless stated otherwise. Earnings per share information related to comprehensive income is not required.

To illustrate the second income statement approach, assume that Obey Company has reported a traditional income statement. The comprehensive income statement is shown in Illustration 20-24.

The computation of "Accumulated other comprehensive income" as reported in stockholders' equity at December 31, 2010, is as follows.

Regardless of the display format for the income statement, the accumulated other comprehensive loss is reported on the stockholders' equity section of the balance sheet of Obey Company as shown in Illustration 20-26. (Illustration 20-26 uses assumed data for the common stock and retained earnings information.)

By providing information on the components of comprehensive income as well as total accumulated other comprehensive income, the company communicates all changes in net assets.

In this illustration, it is assumed that the accumulated other comprehensive income at January 1, 2010, is not adjusted for the amortization of any prior service cost or actuarial gains and losses that would change pension expense. As discussed in the earlier examples, these items will be amortized into pension expense in future periods.

Pension plans are frequently important to understanding a company's financial position, results of operations, and cash flows. Therefore, a company discloses the following information, either in the body of the financial statements or in the notes. [6]

A schedule showing all the major components of pension expense.

Rationale: Information provided about the components of pension expense helps users better understand how a company determines pension expense. It also is useful in forecasting a company's net income.

A reconciliation showing how the projected benefit obligation and the fair value of the plan assets changed from the beginning to the end of the period.

Rationale: Disclosing the projected benefit obligation, the fair value of the plan assets, and changes in them should help users understand the economics underlying the obligations and resources of these plans. Explaining the changes in the projected benefit obligation and fair value of plan assets in the form of a reconciliation provides a more complete disclosure and makes the financial statements more understandable.

A disclosure of the rates used in measuring the benefit amounts (discount rate, expected return on plan assets, rate of compensation).

Rationale: Disclosure of these rates permits users to determine the reasonableness of the assumptions applied in measuring the pension liability and pension expense.

A table indicating the allocation of pension plan assets by category (equity securities, debt securities, real estate, and other assets), and showing the percentage of the fair value to total plan assets. In addition, a company must include a narrative description of investment policies and strategies, including the target allocation percentages (if used by the company).

Rationale: Such information helps financial statement users evaluate the pension plan's exposure to market risk and possible cash flow demands on the company. It also will help users better assess the reasonableness of the company's expected rate of return assumption.

The expected benefit payments to be paid to current plan participants for each of the next five fiscal years and in the aggregate for the five fiscal years thereafter. Also required is disclosure of a company's best estimate of expected contributions to be paid to the plan during the next year.

Rationale: These disclosures provide information related to the cash outflows of the company. With this information, financial statement users can better understand the potential cash outflows related to the pension plan. They can better assess the liquidity and solvency of the company, which helps in assessing the company's overall financial flexibility.

The nature and amount of changes in plan assets and benefit obligations recognized in net income and in other comprehensive income of each period.

Rationale: This disclosure provides information on pension elements affecting the projected benefit obligation and plan assets and on whether those amounts have been recognized in income or deferred to future periods.

The accumulated amount of changes in plan assets and benefit obligations that have been recognized in other comprehensive income and that will be recycled into net income in future periods.

Rationale: This information indicates the pension-related balances recognized in stockholders' equity, which will affect future income.

The amount of estimated net actuarial gains and losses and prior service costs and credits that will be amortized from accumulated other comprehensive income into net income over the next fiscal year.

Rationale: This information helps users predict the impact of deferred pension expense items on next year's income.

In summary, the disclosure requirements are extensive, and purposely so. One factor that has been a challenge for useful pension reporting has been the lack of consistent terminology. Furthermore, a substantial amount of offsetting is inherent in the measurement of pension expense and the pension liability. These disclosures are designed to address these concerns and take some of the mystery out of pension reporting.

In the following sections we provide examples and explain the key pension disclosure elements.

The FASB requires disclosure of the individual pension expense components (derived from the information in the pension expense worksheet column): (1) service cost, (2) interest cost, (3) expected return on assets, (4) other gains or losses component, and (5) prior service cost component. The purpose of such disclosure is to clarify to more sophisticated readers how companies determine pension expense. Providing information on the components should also be useful in predicting future pension expense.

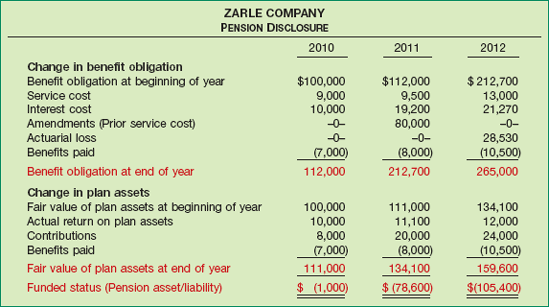

Illustration 20-27 presents an example of this part of the disclosure. It uses the information from the Zarle illustration, specifically the expense component information from the worksheets in Illustrations 20-8 (page 1059), 20-12 (page 1062), and 20-18 (page 1068).

Having a reconciliation of the changes in the assets and liabilities from the beginning of the year to the end of the year, statement readers can better understand the underlying economics of the plan. In essence, this disclosure contains the information in the pension worksheet for the projected benefit obligation and plan asset columns. Using the information for Zarle, the schedule in Illustration 20-28 provides an example of the reconciliation.

The 2010 column reveals that Zarle underfunds the projected benefit obligation by $1,000. The 2011 column reveals that Zarle reports the underfunded liability of $78,600 in the balance sheet. Finally, the 2012 column indicates that Zarle recognizes the underfunded liability of $105,400 in the balance sheet.

Incorporating the corridor computation and the required disclosures, we continue the Zarle Company pension plan accounting based on the following facts for 2013.

Service cost is $16,000.

Settlement rate is 10 percent; expected rate of return is 10 percent.

Actual return on plan assets is $22,000.

Amortization of prior service cost is $17,600.

Annual funding contributions are $27,000.

Benefits paid to retirees during the year are $18,000.

Average service life of all covered employees is 20 years.

Zarle prepares a worksheet to facilitate accumulation and recording of the components of pension expense and maintenance of amounts related to the pension plan. Illustration 20-29 shows that worksheet, which uses the basic data presented above. Beginning-of-the-year 2013 account balances are the December 31, 2012, balances from Zarle's revised 2012 pension worksheet in Illustration 20-18 (on page 1068).

Entries (aa) through (gg) are similar to the corresponding entries previously explained in the prior years' worksheets, with the exception of entry (dd). In 2012 the expected return on plan assets exceeded the actual return, producing an unexpected loss. In 2013 the actual return of $22,000 exceeds the expected return of $15,960 ($159,600 × 10%), resulting in an unexpected gain of $6,040, entry (dd). By netting the gain of $6,040 against the actual return of $22,000, pension expense is affected only by the expected return of $15,960.

A new entry (hh) in Zarle's worksheet results from application of the corridor test on the accumulated balance of net gain or loss in accumulated other comprehensive income. Zarle Company begins 2013 with a balance in the net loss account of $29,940. The company applies the corridor criterion in 2013 to determine whether the balance is excessive and should be amortized. In 2013 the corridor is 10 percent of the larger of the beginning-of-the-year projected benefit obligation of $265,000 or the plan asset's $159,600 market-related asset value (assumed to be fair value). The corridor for 2013 is $26,500 ($265,000 × 10%). Because the balance in Accumulated OCI is a net loss of $29,940, the excess (outside the corridor) is $3,440 ($29,940 − $26,500). Zarle amortizes the $3,440 excess over the average remaining service life of all employees. Given an average remaining service life of 20 years, the amortization in 2013 is $172 ($3,440 ÷ 20). In the 2013 pension worksheet, Zarle debits Pension Expense for $172 and credits that amount to Other Comprehensive Income (G/L). Illustration 20-30 shows the computation of the $172 amortization charge.

Zarle formally records pension expense for 2013 as follows.

Illustration 20-31 (next page) shows the note disclosure of Zarle's pension plan for 2013. Note that this example assumes that the pension liability is noncurrent and that the 2014 adjustment for amortization of the net gain or loss and amortization of prior service cost are the same as 2013.

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974—ERISA—affects virtually every private retirement plan in the United States. It attempts to safeguard employees' pension rights by mandating many pension plan requirements, including minimum funding, participation, and vesting.

These requirements can influence the employers' cash flows significantly. Under this legislation, annual funding is no longer discretionary. An employer now must fund the plan in accordance with an actuarial funding method that over time will be sufficient to pay for all pension obligations. If companies do not fund their plans in a reasonable manner, they may be subject to fines and/or loss of tax deductions.[362]

The law requires plan administrators to publish a comprehensive description and summary of their plans, along with detailed annual reports that include many supplementary schedules and statements.

Another important provision of the Act is the creation of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC). The PBGC's purpose is to administer terminated plans and to impose liens on an employer's assets for certain unfunded pension liabilities. If a company terminates its pension plan, the PBGC can effectively impose a lien against the employer's assets for the excess of the present value of guaranteed vested benefits over the pension fund assets. This lien generally has had the status of a tax lien; it takes priority over most other creditorship claims. This section of the Act gives the PBGC the power to force an involuntary termination of a pension plan whenever the risks related to nonpayment of the pension obligation seem too great. Because ERISA restricts to 30 percent of net worth the lien that the PBGC can impose, the PBGC must monitor all plans to ensure that net worth is sufficient to meet the pension benefit obligations.[363]

A large number of terminated plans have caused the PBGC to pay out substantial benefits. Currently the PBGC receives its funding from employers, who contribute a certain dollar amount for each employee covered under the plan.[364]

A congressman at one time noted, "Employers are simply treating their employee pension plans like company piggy banks, to be raided at will." What this congressman was referring to is the practice of paying off the projected benefit obligation and pocketing any excess. ERISA prevents companies from recapturing excess assets unless they pay participants what is owed to them and then terminate the plan. As a result, companies were buying annuities to pay off the pension claimants and then used the excess funds for other corporate purposes.[365]

For example, at one time, pension plan terminations netted $363 million for Occidental Petroleum Corp., $95 million for Stroh's Brewery Co., $58 million for Kellogg Co., and $29 million for Western Airlines. Recently, many large companies have terminated their pension plans and captured billions in surplus assets. The U.S. Treasury also benefits: Federal legislation requires companies to pay an excise tax of anywhere from 20 percent to 50 percent on the gains. All of this is quite legal.[366]

The accounting issue that arises from these terminations is whether a company should recognize a gain when pension plan assets revert back to the company (often called asset reversion transactions). The issue is complex: in some cases, a company starts a new defined-benefit plan after it eliminates the old one. Thus, some contend that there has been no change in substance, but merely a change in form. However, the FASB disagrees. It requires recognition in earnings of a gain or loss when the employer settles a pension obligation either by lump-sum cash payments to participants or by purchasing nonparticipating annuity contracts. [7][367]

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. (PBGC) recently announced that it would take over responsibility for the pilots' pension plan at United Airlines, to the tune of $1.4 billion. This federal agency, which acts as an insurer for corporate pension plans, has spent much of the past few years securing pension plans for "Big Steel" (U.S. steel companies), and it looks as if airlines are next.

For example, the PBGC also became the trustee of US Airways pilots' pensions in 2003, and it may soon announce a takeover of that struggling carrier's other three pension plans. The grand total at US Airways? It's $2.8 billion—mere pocket change next to the $6.4 billion the PBGC will owe if it has to bail out all four of United Airlines' plans. To date, the airline industry, which makes up 2 percent of participants in the program, has made 20 percent of the claims. The chart below shows how a $6.4 billion bailout would compare with the PBGC's biggest payouts to date.

Source: Kate Bonamici, "By the Numbers," Fortune (January 24, 2005), p. 24.

Hardly a day goes by without the financial press analyzing in depth some issue related to pension plans in the United States. This is not surprising, since U.S. pension funds now hold over $14.4 trillion in assets. As you have seen, the accounting issues related to pension plans are complex. Recent changes to GAAP have clarified many of these issues and should help users understand the financial implications of a company's pension plans on its financial position, results of operations, and cash flows.

The accounting for various forms of compensation plans under iGAAP is found in IAS 19 ("Employee Benefits") and IFRS 2 ("Share-Based Payment"). IAS 19 addresses the accounting for a wide range of compensation elements— wages, bonuses, postretirement benefits, and compensated absences. Both of these standards were recently amended, resulting in significant convergence between iGAAP and U.S. GAAP in this area.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP separate pension plans into defined-contribution plans and defined-benefit plans. The accounting for defined-contribution plans is similar.

For defined-benefit plans, both iGAAP and U.S. GAAP recognize the net of the pension assets and liabilities on the balance sheet. Unlike U.S. GAAP, which recognizes prior service cost on the balance sheet (as an element of "Accumulated other comprehensive income"), iGAAP does not recognize prior service costs on the balance sheet. Both GAAPs amortize prior service costs into income over the expected service lives of employees.

Another difference in defined-benefit recognition is that under iGAAP companies have the choice of recognizing actuarial gains and losses in income immediately or amortizing them over the expected remaining working lives of employees. U.S. GAAP does not permit choice; actuarial gains and losses (and prior service costs) are recognized in "Accumulated other comprehensive income" and amortized to income over remaining service lives.

The IASB has recently issued a discussion paper on pensions proposing: (1) elimination of smoothing via the corridor approach, (2) a different presentation of pension costs in the income statement, and (3) a new category of pensions for accounting purposes—so-called "contribution-based promises."

The FASB and the IASB are working collaboratively on a postretirement benefit project. As discussed in the chapter, the FASB has issued GAAP rules addressing the recognition of benefit plans in financial statements. The FASB has begun work on the second phase of the project, which will reexamine expense measurement of postretirement benefit plans. The IASB also has added a project in this area, but on a different schedule. The IASB is monitoring the FASB's progress and hopes to issue a converged standard in this area by 2010.

In March 1991 IBM's adoption of a new GAAP requirement on postretirement benefits resulted in a $2.3 billion charge and a historical curiosity—IBM's first-ever quarterly loss. General Electric disclosed that its charge for adoption of the same GAAP rules would be $2.7 billion. In the fourth quarter of 1993, AT&T absorbed a $2.1 billion pretax hit for postretirement benefits. What is GAAP in this area, and how could its adoption have so grave an impact on companies' earnings?

After a decade of study, the FASB in December 1990 issued GAAP rules on "Employers' Accounting for Postretirement Benefits Other Than Pensions." [8] It alone was the cause for the large charges to income cited above. These rules cover for healthcare and other "welfare benefits" provided to retirees, their spouses, dependents, and beneficiaries.[368] These other welfare benefits include life insurance offered outside a pension plan; medical, dental, and eye care; legal and tax services; tuition assistance; day care; and housing assistance.[369] Because healthcare benefits are the largest of the other postretirement benefits, we use this item to illustrate accounting for postretirement benefits.

For many employers (about 95 percent) these GAAP rules required a change from the predominant practice of accounting for postretirement benefits on a pay-as-you-go (cash) basis to an accrual basis. Similar to pension accounting, the accrual basis necessitates measuring the employer's obligation to provide future benefits and accrual of the cost during the years that the employee provides service.

One of the reasons companies had not prefunded these benefit plans was that payments to prefund healthcare costs, unlike excess contributions to a pension trust, are not tax-deductible. Another reason was that postretirement healthcare benefits were once perceived to be a low-cost employee benefit that could be changed or eliminated at will and therefore were not a legal liability. Now, the accounting definition of a liability goes beyond the notion of a legally enforceable claim; the definition now encompasses equitable or constructive obligations as well, making it clear that the postretirement benefit promise is a liability.[370]

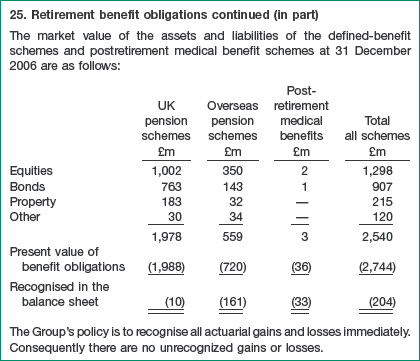

The FASB used the GAAP rules on pensions as a reference for the accounting prescribed for healthcare and other nonpension postretirement benefits.[371] Why didn't the FASB cover these other types of postretirement benefits in the earlier pension accounting statement? Because the apparent similarities between the two benefits mask some significant differences. Illustration 20A-1 shows these differences.[372]

Two of the differences in Illustration 20A-1 highlight why measuring the future payments for healthcare benefit plans is so much more difficult than for pension plans.

Many postretirement plans do not set a limit on healthcare benefits. No matter how serious the illness or how long it lasts, the benefits continue to flow. (Even if the employer uses an insurance company plan, the premiums will escalate according to the increased benefits provided.)

The levels of healthcare benefit use and healthcare costs are difficult to predict. Increased longevity, unexpected illnesses (e.g., AIDS, SARS, and avian flu), along with new medical technologies and cures, cause changes in healthcare utilization.

Additionally, although the fiduciary and reporting standards for employee benefit funds under government regulations generally cover healthcare benefits, the stringent minimum vesting, participation, and funding standards that apply to pensions do not apply to healthcare benefits. Nevertheless, as you will learn, many of the basic concepts of pensions, and much of the related accounting terminology and measurement methodology, do apply to other postretirement benefits. Therefore, in the following discussion and illustrations, we point out the similarities and differences in the accounting and reporting for these two types of postretirement benefits.

For many companies, other postretirement benefit obligations (OPEBs) are substantial. Generally, OPEBs are not well funded because companies are not permitted a tax deduction for contributions to the plan assets, as is the case with pensions. That is, the company may not claim a tax deduction until it makes a payment to the participant (pay-as-you-go).

Presented below are companies with the largest OPEB obligations, indicating their relationship with other financial items.

So, how big are OPEB obligations? REALLY big.

Source: Company reports.

Healthcare and other postretirement benefits for current and future retirees and their dependents are forms of deferred compensation. They are earned through employee service and are subject to accrual during the years an employee is working.

The period of time over which the postretirement benefit cost accrues is called the attribution period. It is the period of service during which the employee earns the benefits under the terms of the plan. The attribution period, shown in Illustration 20A-2 for a hypothetical employee, generally begins when an employee is hired and ends on the date the employee is eligible to receive the benefits and ceases to earn additional benefits by performing service, the vesting date.[373]

In defining the obligation for postretirement benefits, the FASB maintained many concepts similar to pension accounting. It also designed some new and modified terms specifically for postretirement benefits. Two of the most important of these specialized terms are (a) expected postretirement benefit obligation and (b) accumulated postretirement benefit obligation.

The expected postretirement benefit obligation (EPBO) is the actuarial present value as of a particular date of all benefits a company expects to pay after retirement to employees and their dependents. Companies do not record the EPBO in the financial statements, but they do use it in measuring periodic expense.

The accumulated postretirement benefit obligation (APBO) is the actuarial present value of future benefits attributed to employees' services rendered to a particular date. The APBO is equal to the EPBO for retirees and active employees fully eligible for benefits. Before the date an employee achieves full eligibility, the APBO is only a portion of the EPBO. Or stated another way, the difference between the APBO and the EPBO is the future service costs of active employees who are not yet fully eligible.

Illustration 20A-3 contrasts the EPBO and the APBO.

At the date an employee is fully eligible (the end of the attribution period), the APBO and the EPBO for that employee are equal.

Postretirement expense is the employer's annual expense for postretirement benefits. Also called net periodic postretirement benefit cost, this expense consists of many of the familiar components used to compute annual pension expense. The components of net periodic postretirement benefit cost are as follows. [10][374]

Service Cost: The portion of the EPBO attributed to employee service during the period.

Interest Cost: The increase in the APBO attributable to the passage of time. Companies compute interest cost by applying the beginning-of-the-year discount rate to the beginning-of-the-year APBO, adjusted for benefit payments to be made during the period. The discount rate is based on the rates of return on high-quality, fixed-income investments that are currently available.[375]

Actual Return on Plan Assets: The change in the fair value of the plan's assets adjusted for contributions and benefit payments made during the period. Because companies charge or credit the postretirement expense for the gain or loss on plan assets (the difference between the actual and the expected return), this component is actually the expected return.

Amortization of Prior Service Cost: The amortization of the cost of retroactive benefits resulting from plan amendments. The typical amortization period, beginning at the date of the plan amendment, is the remaining service periods through the full eligibility date.

Gains and Losses: In general, changes in the APBO resulting from changes in assumptions or from experience different from that assumed. For funded plans, this component also includes the difference between actual return and expected return on plan assets.

Like pension accounting, the accounting for postretirement plans must recognize in the accounts and in the financial statements effects of several significant items. These items are:

The EPBO is not recognized in the financial statements or disclosed in the notes. Companies recompute it each year, and the actuary uses it in measuring the annual service cost. Because of the numerous assumptions and actuarial complexity involved in measuring annual service cost, we have omitted these computations of the EPBO.

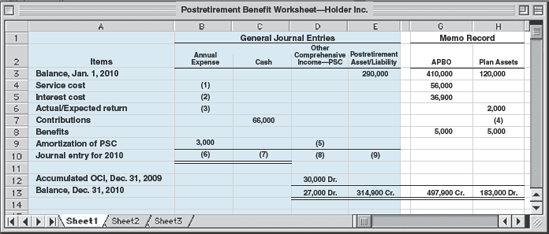

Similar to pensions, companies must recognize in the financial statements items 2 through 5 listed above. In addition, as in pension accounting, companies must know the exact amount of these items in order to compute postretirement expense. Therefore, companies use the worksheet like that for pension accounting to record both the formal general journal entries and the memo entries.

To illustrate the use of a worksheet in accounting for a postretirement benefits plan, assume that on January 1, 2010, Quest Company adopts a healthcare benefit plan. The following facts apply to the postretirement benefits plan for the year 2010.

Plan assets at fair value on January 1, 2010, are zero.

Actual and expected returns on plan assets are zero.

Accumulated postretirement benefit obligation (APBO), January 1, 2010, is zero.

Service cost is $54,000.

No prior service cost exists.

Interest cost on the APBO is zero.

Funding contributions during the year are $38,000.

Benefit payments to employees from plan are $28,000.

Using that data, the worksheet in Illustration 20A-4 presents the postretirement entries for 2010.

Entry (a) records the service cost component, which increases postretirement expense $54,000 and increases the liability (APBO) $54,000. Entry (b) records Quest's funding of assets to the postretirement fund. The funding decreases cash $38,000 and increases plan assets $38,000. Entry (c) records the benefit payments made to retirees, which results in equal $28,000 decreases to the plan assets and the liability (APBO).

Quest's December 31 adjusting entry formally records the postretirement expense in 2010, as follows.

The credit to Postretirement Asset/Liability for $16,000 represents the difference between the APBO and the plan assets. The $16,000 credit balance is a liability because the plan is underfunded. The Postretirement Asset/Liability account balance of $16,000 also equals the net of the balances in the memo accounts.

Illustration 20A-5 shows the funded status reported in the balance sheet. (Notice its similarity to the pension schedule.)