Chapter 8

Tax Policy: Does Cutting Taxes Cure All Ills?

When it comes to government policy, nothing causes more arguments than taxes. Everyone knows that to provide services you have to pay for them. But what are “good” taxes, if there actually are such things, and which ones should be cut is a totally different story. Basically, everyone wants their taxes cut while keeping taxes on everyone else.

But even if you cut taxes, you can do it the right way or the wrong way. Some tax cuts can create significantly more economic activity but many other do almost nothing to improve the economy.

We need also recognize that cutting taxes is expensive, as every person or company is eligible for the tax if they meet certain conditions, regardless of whether they make use of that extra money. Some firms get a tax break even if they continue operating exactly the same as they before the tax break happened. And since households of varying income levels spend the extra income from reduced taxes at a different pace, who gets the tax break makes a significant difference. Therefore, the distribution of income is a major player in the effectiveness of tax policy. In other words, if the tax cut doesn't make economic sense, it simply becomes a way to redistribute income, not a way to expand growth.

But politicians still love to say that all you have to do is cut taxes and everything will be right with the world, which is why one of our favorite sayings is: if you get your tax policy from a politician, you get the tax code you deserve.

There Is No Such Thing as a Free Tax Cut

Benjamin Franklin is credited with saying that “in this world nothing can be said to be certain except death and taxes.” That may be true, but few people like to pay taxes so we do everything possible to escape them.

Tax reform, or how we should cut taxes and who should get those tax cuts, will forever be a hot-button issue. This anger about taxes is not something the modern Tea Party, invented as it came from the original Tea Tax protesters. But the fact that a tax is cut doesn't mean the tax cut makes any economic sense. Indeed, there are many examples of abusive tax subsidies hidden in the tax code that did little other than benefit a specific firm, industry, or group.

Since most of us cannot afford the best tax lawyers to scour every nook and cranny of the tax code to ensure that we pay the least amount possible, we demand tax breaks through the ballot box. That raises the question, “What taxes should be cut?” The usual response is “mine”! Unfortunately, that is not the best answer for the economy.

How, then, do you determine when a tax break makes economic sense? Use the Acid Test for tax changes: That is, Only cut a tax if it adds significantly to economic activity and if a current tax break doesn't, it should be repealed. A tax break that does not pass the Acid Test is a social welfare program that transfers money from the Treasury to those who get the break.

This is a simple concept that hinges on the basic fact that there is no such thing as a free tax cut. When you reduce a tax, to start with, the government loses revenue, and either households or corporations have more money in their pockets or banks. It is what is done with those additional funds and the cost to the government of providing those breaks, in other words, the benefits versus the costs of the tax cuts, that determine if the action on the part of our elected officials to provide tax relief actually accomplishes anything.

The purpose of the tax cut is to generate more spending on the part of either households or businesses. If personal income taxes are reduced, people find their paychecks are fatter. Individuals have the capacity to buy more goods or services, and that would, at least in theory, grow the economy. Businesses that benefit from the greater consumer demand can hire more people, adding to personal income and ultimately creating additional consumption.

When corporate taxes are cut, the company has more cash. A business tax reduction could, in theory, allow firms to expand production, hire more people, or invest in machinery, software, or even a new plant. That, too, should lead to greater economic growth.

All that makes total sense, as long as the tax cut actually achieves those goals. But not all tax cuts actually generate very much additional economic activity. If they don't, there are still some people or businesses that have more money, but the economy doesn't grow very much as a result, and tax revenues fall, expanding the budget deficit.

There are many examples of tax reductions that on the surface seem to make a lot of sense but in reality don't do a lot. Here are three:

Example 1: The inheritance/estate/death tax. A reduction or ending of this tax completely would add absolutely nothing to economic growth. Nothing. Nada. And there is no way around that. This is purely a social welfare program for the heirs of those who have created lots of wealth. That may not be bad, but that is all it is.

Why doesn't cutting the inheritance tax make any economic sense? Simple. The key is that the tax falls on the heirs, not on those who actually create the wealth. They are dead, thus the moniker death tax.

Since the wealth creators don't pay taxes as long as they are alive, it does not affect their economic or business decisions. Successful businesspeople don't sit around saying they will not create more wealth because after they die their heirs might have to pay more taxes. They may hire tax specialists to protect their wealth, but they will not stop creating it.

The reality is that lowering the inheritance tax will not encourage any additional wealth-creating economic activity. Consequently, an inheritance tax cut simply amounts to a transfer of income to the heirs. Worse, if the tax is repealed, it could lower activity by ending the need for the tax-planning industry. Now we are not arguing that there is any economic value derived from having all those tax accountants and lawyers running around devising ways of preventing the government from getting its hands on their clients money, but to the extent that that they are no longer needed and their businesses fail, the economy is negatively affected.

Regardless, the Acid Test argues that this tax should not be lowered.

Example 2: Carried interest. Carried interest is, in simple terms, a reduced tax rate available to those who manage alternative investments, usually private equity and hedge fund managers. Part of their income is taxed at the lower capital gains rate rather than the higher wage rate.

Should this tax break exist? It is hard to see why. Does anyone really believe hedge fund or private equity managers would get out of the business if they had to pay regular income taxes rather than the reduced rate? Really, come on now.

But let's say some managers do quit—would that even matter? Since they are investing other people's money, their investors would simply have to find new managers who have remained in the business. And there will be many other very successful investment advisers and managers who would be glad to take the money from their former competitors and employ those funds.

There could be some short-term dislocations as investors transition from one hedge fund to another, but ending the carried interest deduction would not reduce the availability of capital or economic activity significantly.

The Acid Test argues that the carried interest break should be terminated, as all it does is transfer money to a special class of money managers by lowering their tax rate.

Example 3: Mortgage interest deduction. The mortgage interest deduction is supposed to lower homeowner payments, thus increasing housing demand. Wrong. Interest payments are only one part of the “price” of a home: Homebuyers look at total monthly payments, which include principal and taxes as well as interest. Critically, mortgage companies don't qualify people on the basis of after-tax payments.

But, more important, when making their monthly mortgage payments, do homeowners really perceive they are paying less? Doubtful. Instead, when they file their taxes, they see it as lower tax payments or higher refunds, not a reduction in housing costs. That is, homeowners don't look at their tax returns and say that the tax refund that could be ascribed to the mortgage deduction all goes to the house. They allocate it across their entire living expenses, of which housing is just a part.

Ending the mortgage interest deduction would not significantly affect housing sales so the Acid Test would say end it.

There are many other examples of major tax breaks, including the investment tax credit, reduced dividends tax rates, zero taxes on municipal bonds, and lowered rates for interest and capital gains, which fail the Acid Test. These sound good on the surface, but when you look at their economic effects, their value disappears.

But it is not just a specific type of tax that could fail the Acid Test. How the tax is implemented, that is, who gets the tax break and how much, is always critical.

How Much Do Americans Make and What Are They Taxed?

Here are some things that are not very common: blue moons; nohitters in baseball, and income tax increases.

Yes, read my lips, Congress does occasionally raise taxes on Americans' paychecks. It's painful for many legislators to raise taxes, but sometimes they are left with few places to get some revenue.

A recent case in point: a piece of legislation called the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA), passed by Congress on New Year's Day 2013. That's also the bill that temporarily prevented the United States from going over the so-called fiscal cliff, a series of across-the-board tax increases and spending cuts that would have been implemented if Congress did not act.

As it turned out, two months later, the automatic cuts went into effect but the ATRA maintained what is referred to as the Bush-era cuts and increased taxes on high-income wage earners, specifically for couples earning more than $450,000 a year or single filers earning more than $400,000 a year. Their top tax rate went from 35 percent to 39.6 percent. They also got hit with a higher capital gains rate that went from 15 percent to 20 percent. And they ended up paying a surcharge on income of over $250,000 for a couple ($200,000 for singles) related to President Obama's health care bill.

But, most taxpayers avoided higher income taxes though they did once again pay their full share of Social Security taxes, which had been reduced. How much more will higher income wage earners have to pay in taxes?

In July 2013, the Tax Policy Center (TPC), a joint venture of the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution, published a model estimating Americans' incomes and tax burdens for tax year 2014. For its computer projection, the TPC incorporated a variety of factors such as historical tax records, government revenue estimates, and the economic projections of the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, which projected the gross domestic product would grow by a moderate 3.4 percent in 2014. In estimating income, the TPC used a broad measure that included the value of employer-provided benefits, interest from tax-exempt bonds, and money saved for retirement that is not subject to taxation. In estimating taxes, the TPC included four federal taxes: income taxes, payroll taxes (Social Security and Medicare), the individual share of corporate taxes, and the estate tax.

The TPC's estimates of Americans' incomes and taxes are shown in Table 8.1. All the tax rates are permanent unless Congress decides to change them again.

While the Distribution of Income Is Good or Inevitable, It Still Matters When It Comes to Tax Policy

Consider the issue of income distribution and how it could affect the way we tax income. This is not a class warfare issue; it is an economic activity issue. If you start with an economy that is largely dependent on consumer spending, you want an economy where as much of the income earned will be spent. That is where income distribution becomes a real factor in the level and make up of consumer spending.

Table 8.1 Estimated Income and Taxes for 2014a

Economists have a term called marginal propensity to spend, which comes into play when you deal with the issue of consumption and income distribution. This is really a very simple concept wrapped around a complex term. Essentially, it comes down to this: how much does an individual spend when he or she gets another dollar of income? Okay, it's not just another dollar; it could be a hundred or a thousand or a million dollars, but you get the point.

The theory argues that low-income households tend to spend just about all the income they earn because they have to. Most of the money is used for essentials such as food, shelter, heating, transportation, and clothes. The poorest frequently don't even have enough money to cover their basic needs. Therefore, any additional funds that these households receive generally get spent. Their propensity is to spend everything.

As incomes rise and people can meet their basic needs, they start buying discretionary goods. They don't need them, or at least all of them, but they like to have them. Whether it's a shoe fetish or the desire to have different shirts for every day of the year, once incomes reach a significantly high enough level, people purchase products they want rather than need.

Once a household's funds reach what we will call “middle-income” levels, families have the choice to save some of their earnings or spend it all—or more, which is the issue of debt that we have discussed. Generally, some of the income is saved, even if it is a small amount. That is, as middle-income households get more money, their propensity is to spend most but not all of their income. It is lower than the poor but often not that much lower.

Finally there are “upper-income” households. They can buy all they need, all they want, and still have some left over. They save a lot, generally by investing their extra funds. That is good because these are resources that the capital markets can make available to households and businesses to borrow. However, it also means that propensity to consume by the household that earns tons of money is a lot lower than those who are either middle income or lower income. Very simply, the higher the income, the more that is saved, and therefore the less that is spent.

The Occupy Movement made Wall Street a symbolic target in its effort to highlight income disparity. But lower Manhattan is not the only place where households have large incomes.

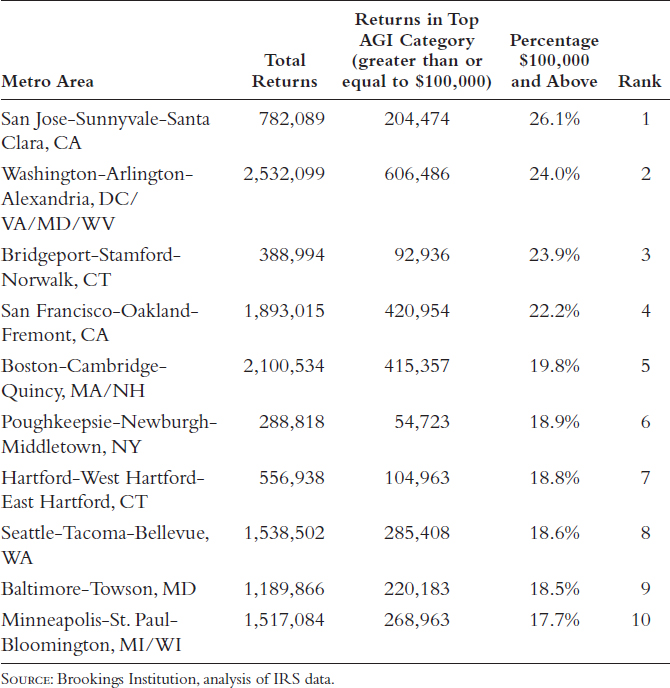

In September 2013, the Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program, using IRS data from taxes filed for 2011, looked to see where those with the highest incomes lived.

Although the Occupy protestors focused on the top 1 percent, the IRS does not break down income on the basis of zip code until $100,000 because of privacy concerns. What that reveals is where the top 12 percent live, calculates the TPC.

The Metropolitan Policy Program found that 75 percent live in the 100 largest metropolitan areas as opposed to rural areas. In some of the metro areas, wealthy suburbs help to boost incomes such as the suburbs around Washington, D.C., or the Cambridge area of Boston.

Four out of the top 10 metro areas in terms of percentage of filers with returns of over $100,000 are on the West Coast. Think of the entertainment industry in Los Angeles, Silicon Valley in northern California, the financial and creative hub of San Francisco, and Seattle, home of Microsoft.

Elizabeth Kneebone, a fellow at Brookings who put together the analysis, observes that the metro areas with the highest incomes have certain characteristics: a high level of education, an entrepreneurial bent, the proximity to a major financial or creative center, and an industry or corporate entity that pays its employees relatively high wages.

“Many of the areas have a highly skilled and highly educated concentration of workers,” says Kneebone, who is the co-author of Confronting Suburban Poverty in America (Brookings Institution Press, May 2013).

The New York metro area is not in the top 10 on the basis of share of filers earning over $100,000. It ranks fourteenth. However, many people who work on Wall Street actually live in coastal Connecticut, which ranked third. In addition, as Kneebone notes, New York has over 1.4 million people making over $100,000, the most numerically of any metro area.

Using the $100,000 or higher criteria, Table 8.2 shows the Brookings Metropolitan Policy's top 10 most wealthy areas.

Table 8.2 Shares of Tax Filers with Adjusted Gross Incomes of $150,000 or Higher in Tax Year 2011

Why should income distribution matter? An example is the best way to show how income distribution and spending matters. Let's assume that a household gets an additional $10,000. Someone living in poverty is likely to spend just about all of it. It is enough to allow them to buy what they need but not enough to make them rich, however that is defined.

Meanwhile, if it's the middle-income household who gets the extra money, they are likely to save some of it but still spend a significant portion of it. They have lots of discretionary items they would like to purchase. They can afford to put some away for a rainy day, which they are likely to do. Thus, they spend less of the extra money than a poor family would.

What about upper-income households? The extra money is nice but does not change the standard of living a whole lot. They are already buying all the necessities and discretionary items they want and they are still saving and investing extensively. Not much of the extra funds, if any at all, get spent.

Given this example, what happens to spending if incomes go up by $10,000? It depends on who gets the money. If it goes to the poor, probably all of it gets spent, so demand rises robustly. If it goes to middle-income households, most of it is spent, and demand goes up strongly. If it goes to upper-income households, little is spent, so demand barely rises.

Now consider the distribution of income. This is something that has been worrying economists, politicians, and average households for years. Basically, it should seem clear now that how the income that is earned in the economy gets distributed between income groups can have a major impact on economic growth.

That raises the basic question of whether there is a good distribution of income. While there may be implications for growth of different types of income distributions, it is difficult to say that over time one type of distribution is best. However, when it comes to economic growth, some are better than others.

For example, if 1 percent of the population gets 99 percent of the income and those “1-percenters” don't spend a lot of the money, economic growth is likely to be quite sluggish. However, if everyone has the same income, there may be limited savings, and that could reduce capital availability and investment, reducing future growth. Clearly, somewhere between equal distribution and total concentration of income is a “good” one, but it is hardly clear what that is.

In addition, there may be nothing that can be done about it even if we wanted to. Technological change, which puts a premium on high-skilled workers, is a major factor. Technology also reduces the demand for lower-skilled employees, keeping their wages in check.

Similarly, the globalization of economies is creating tremendous restraining pressures on wages as labor supply is now international in scope, not just domestic. If you can produce anywhere, workers all across the globe become potential employees. That allows owners of capital to keep wages down and reap a larger share of the returns. Since there is no turning back on globalization or technical change, the changing patterns in income distribution may be inevitable.

That doesn't mean there is no reason to consider the changes in income distribution: it creates political issues and problems even outside the economic concerns. The Occupy Wall Street movement, which came and went quickly, should not be dismissed. It represented a group of disenfranchised individuals that may not have moved a lot of people to action but whose ideas may be present in a lot of workers.

Disenfranchised employees are not nearly as productive as those who feel they can make their way up the corporate and income ladders. They do their jobs, but a firm doesn't make a lot of profits because a worker gives them a dollar's day of work for a dollar's pay. It is the worker that goes the extra mile that creates the added product and ultimately the most earnings. Profits come from firms paying for a day's work but getting more than a day's output.

While there are reasons to consider the impacts of the income distribution, the attempts to politicize the issue, especially the incessant use of the phrase class warfare, hides the economic discussions. It is not whether the distribution of income is good, but what are the implications for economic growth, consumer and government spending, the budget deficit, and the availability of capital of the changing income distribution.

With that in mind, in the short term, the shifting distribution is already having real economic implications. In the United States, the income distribution has been moving more toward upper-income households. This has been nicknamed the “bar-belling” of income as more gets concentrated in upper- and lower-income groups.

A report by Linda Levine for the Congressional Research Service concluded that “inequality has increased in the United States as a result of high-income households pulling further away from those lower in the distribution.”1 It is in that context that the economic implications need to be discussed.

The winnowing out of the middle class is restraining consumer spending and therefore economic growth. The middle class has been the driving force for the economy since the 1950s. They are the key to the consumer-based spending. But as income flows upward and more people move down the income ladder, consumption growth potential declines.

The more income that moves to households with lower propensities to consume, the lower the growth of the economy since the share of income going to spending would decline. That is particularly worrisome for an economy that depends heavily on household spending.

In addition, there is a potential change in the types of goods demanded both in terms of categories and where they are produced. Upper-income households buy more discretionary products and fewer necessities. Are more of those goods imported, or are they produced domestically? Since most food and housing are domestically sourced, changing income patterns might lead to rising imports. That is not clear, but it is a potential outcome.

While income distribution per se is not the most important factor in the economy, how incomes change matters. Thus, understanding how the economy is growing requires not just income growth but also income distributional issues. The context or income change—when and how quickly that is occurring—makes context once again a key factor in evaluating the economy.

Indeed, was it any surprise that the economic recovery was so slow given that workers' incomes hardly kept up with inflation but management and business owners' profits soared? If it was, it was because observers didn't account for who was getting the earnings from the growing economy, only that those earnings were expanding. They missed the whole idea of income growth in the context of who gets the growing income.

Is the Answer to Every Economy Ill to Cut Corporate Taxes?

We talked about the reality that businesspeople respond in ways that are similar to households in that their reactions to tax policy is greatly affected by the context in which those policies were implemented and their corporate financial outlook. If the Acid Test is to be used, those factors need to be considered when corporate tax changes are considered.

Since companies create jobs, helping firms along is always a popular approach to economic policy. The problem is that tax cuts are very expensive because of the way they are structured: everyone who is qualified gets the tax break even if the tax break doesn't induce them to do anything differently from what they would normally do.

Consider the investment tax credit. The logic of this break is to increase the level of investment in the economy. That makes total sense, as improving technology and production expands the economy's capacity and therefore its growth potential. There is nothing better for long-term growth than robust business investment.

How could implementing something like an investment tax credit be anything but good? While the purpose of a tax cut is to induce additional spending, it is not limited to only those firms who are incented to invest. Anyone who actually invests gets to take advantage of the reduced costs.

A simple mathematical example can best illustrate the issue. Let's say that business investment is running at $1 trillion a year and the economy needs a boost. Let's also assume that without an investment tax break, we would still have only $1 trillion in investment. That is, the level of business investment would be flat without some government incentives.

It would seem that the prospects of no growth in capital spending would be a really good time to cut business taxes, and it would be. And let's say it works extremely well so that instead of zero additional investment, capital spending grows by a whopping 15 percent. The tax break creates $150 billion more spending. Wow, what a great move, right? Maybe. Maybe not.

Before you take out the axes and start cutting investment taxes like crazy, you also have to consider the costs to the Treasury of reducing the tax. Here is where the difference between economics and politics can be seen the clearest. An economist would say that you only give the tax break to those firms who would not have invested in the new machinery but because of the reduced costs decide to make the investment. The politician says you cannot do that (and in reality it would be impossible to make that determination), you have to give everyone who invests the deal.

It's the universality of the tax break that creates the real problems with tax policy. The government has not only reduced taxes on the firms that decided to purchase the additional $150 billion of new capital, but it has also given a tax break to all those companies that were going to invest anyway. Remember, without the cut, there still would have been $1 trillion in capital spending.

Without the tax break, the firms that spent the first $1 trillion on capital would pay the government the old, higher tax rates. Instead, the Treasury collects reduced taxes from those companies, again, not because they were induced to invest but because they did what they were going to anyway. That is, the government's tax take from all those companies is reduced.

Let's say that the tax credit reduces corporate taxes by 10 percent of the cost of capital. That would mean the government loses roughly $100 billion –10 percent of $1 trillion. But only an additional $150 billion is spent by firms. That implies the government pays for about two-thirds of the cost of the new capital. What a deal!

The dirty little secret of corporate tax cuts is that firms benefit simply because they exist. Believe it or not, lots of politicians actually think it is a perfectly acceptable thing for the government to pay firms for doing nothing, but that is precisely what happens with tax breaks.

Clearly, this is just an example, and there are a lot of other factors that go into determining the benefits and costs of a tax cut. For example, the additional spending would multiply though the economy and could generate more than $150 billion in growth. The taxes on that would offset some of the lost revenue. But the point still holds: When government reduces taxes, everyone benefits even if they do not change their behavior one bit. And that costs the Treasury real money. The economic research on tax cuts is clear: they do not pay for themselves, at least in the first few years after they are implemented.

Should we ever cut taxes on businesses? The answer is yes, but you need to get a really big bang for the bucks that the Treasury loses. The best time is early in a recovery, as the impact will be multiplied. The impression that the economy will strengthen because of the increased investment activity caused by the tax breaks would lead to rising corporate confidence. That could generate significant additional growth even in unrelated industries, as most business leaders build a better economy into their business plans. But once there is a solid, broad-based expansion and most sectors are standing on their own, those added impacts are limited and business tax cuts only transfer income from the Treasury to businesses. It is a form of income redistribution.

That said, there are some taxes on businesses that really do need to be reexamined extremely closely. One is the so-called double taxation of small-business owner income. Basically, most small-business people pay personal, not corporate, income taxes. As such, all revenues their businesses earn are essentially personal income.

Unfortunately for the average small-business owner, when they take home a paycheck, they pay taxes for Social Security (FICA) and Medicare twice. First, they pay it out of their own paycheck. But that is not enough for the government. Since small-business owners are also employers, they have to pay the business share of FICA and Medicare taxes, which as it turns out is exactly the same as the employee pays.

What does that mean? The Social Security tax rate is 6.2 percent of income up to a cutoff point. The Medicare portion is 1.45 percent on all income. Thus, the small-business owner pays 12.4 percent for Social Security (6.2 percent for being an employee and 6.2 percent as the employer) and 2.9 percent for Medicare (1.45 percent for being an employee and 1.45 percent as an employer). The result is that before paying anything else, including income taxes, small-business owners pay the federal government 15.3 percent of their income up to the Social Security maximum.

Since most small-business owners earn less than the Social Security maximum, the starting tax rate is a real business killer. What that tells us is that one of the best ways to generate more hiring is to allow small-business owners to be responsible for only the employee portion of the payroll taxes. That would generate significant savings. Since most small-business owners plow much of their earnings back into the business, they will likely be able to afford more inventories and/or part-time workers.

The lack of rational approaches to small-business taxes makes no sense at all. These firms create most of the jobs. At times during the first few years of the recovery from the Great Recession, ADP, a payroll services company, indicated from their surveys that almost all the private-sector payroll increases came from firms that employed less than 500 workers.2 Similar results can be seen in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Business Employment Dynamics reports for the past few years. Indeed, the importance of small businesses in job creation has not just been during the recovery but BLS's data show that between 1993 and 2013, nearly 64 percent of the net new jobs came from businesses of employing fewer than 500 workers.3 If you don't pay more than lip service to small businesses, you don't get much growth.

These issues of income distribution and the costs of tax breaks matter because of their impacts on the deficit. Basically, if you lose tax revenues through a tax change, the deficit widens. That growing debt can be paid in just three ways: by reducing spending, raising other taxes, or borrowing. Each has redistributional impacts.

Let's assume that the rising budget deficit that results from an inefficient tax cut is dealt with through cutting spending. We cannot afford to pay for everything, so let's eliminate some programs. While that sounds good, government spending cuts don't come without a price. Some person, group, or company loses.

If the government reduces its purchases of goods and services, businesses that had contracts to supply those products now are looking at reduced order books. Their incomes fall and they cut back on employees and buy fewer inputs. That reduces economic activity further. We have a redistribution of income from those firms that lose business and their employees and suppliers to those who pay lower taxes.

If the tax cut is paid for by borrowing, a similar redistribution takes place. Future generations pay for the spending of the current generation. Of course, if those tax breaks do create a lot of new investment that increases society's long-term productive capacity, we could have a trade-off. But, in general, as we saw in the example about all those firms that get the tax break for simply breathing, that is usually a stretch of the imagination.

Finally, we can raise other taxes. That redistribution is very obvious. Those who pay the higher taxes give money to those who pay lower taxes. Is that fair? Only if you are comfortable saying that one group of people should have more money while others have less. And that gets us back to the entire distribution-of-income discussion.

But the discussion of tax changes and their impacts on the economy doesn't stop with the high cost of businesses taxes or the problems of how the distribution of income affects tax policy; there is the key concern about messages that it sends: if tax breaks are given to those activities that are deemed to have special value, what does it say about those activities that are taxed at higher rates? Policymakers are indicating they consider the competing activities to be of lower value.

Think about it. The tax code seems to be saying that people should earn their income from almost any means other than labor. Why? Wages and salaries are taxed at just about the highest rate of any income source. There are special lowered rates for dividends, capital gains, and interest income—especially from state and local debt—but if all you do is make your money from wages and salaries, you pay a higher tax rate.

Consider the tax-free treatment of interest on state and local government securities. Most state and local governments issue bonds for schools, roads, and other infrastructure projects, and no federal income tax means that interest on the securities can be reduced. That increases construction by making the projects more affordable.

Interestingly, the federal government taxes interest paid on its own debt. That creates a strange commentary about federal activities: If you lower the tax to encourage one type of activity but don't lower it on similar types of activity, you are basically saying the higher-taxed activity is less worthy. Do members of Congress really believe that their spending has less value than what municipal governments do? And do we really want to encourage more local construction or borrowing?

It is possible, if all your income is municipal bond interest, that you could pay no taxes at all. At the least, those who earn interest from munis will pay much lower taxes than those who earn the same amount of wages or salaries. What is the government saying? Investing in municipal debt is an awful lot more desirable than working for a living. Quite an interesting message, isn't it?

Similarly, there is the issue of the so-called double taxation of dividends, which are currently taxed at a 15 percent rate rather than the more typical 25 percent to 35 percent rate on income. The argument is that corporations already pay taxes on that income. If the owners of the corporations, the stockholders, have to pay taxes on that income as well, the company income is actually taxed twice.

While the double-taxation argument may have merit, the reduced tax rate affects only those stockholders of companies that pay dividends. Stockholders in so-called “growth” companies, which tend not to pay dividends, don't get that benefit. Is the government really trying to encourage dividend payouts rather than faster business growth? Once again, those who receive income from dividends rather than wages will pay lower taxes.

Finally, there are capital gains, where the reduced tax rate of 15 percent for most filers was supposed to foster saving and investment. However, over the long run, neither households nor businesses invest based on tax rates. Also, capital is raised internationally, so why a lower or higher tax rate would affect a foreign investor is anyone's guess. The result, though, is those who earn income from capital gains pay lower taxes.

By imposing higher tax rates on wages and salaries compared to interest, dividends, or capital gains, the tax code clearly values investment income more than labor income. If Congress really wants to encourage work effort, it should show it by lowering the tax on wages and salaries compared to other income sources. If it doesn't want to show a preference, then it should consider all income as being equal and tax all sources similarly.

When it comes to taxes, it is not clear that cutting taxes is the answer. It could be, but you have to cut those taxes that create the most additional economic value and don't send negative messages to certain groups or businesses. It is not very often that we see our friendly politicians talk about how much more economic activity is generated by their tax proposals or compare the positive impacts on the economy with the costs. Normally, the tax cuts occur in the dead of night when no one is looking so the hard questions don't have to be answered.

Unfortunately for all of us, there are few politicians that haven't seen a tax cut that they couldn't support and explain why it is so great, even if it isn't. Which gets us back to another favorite saying: If you get your tax policy from a politician, you get the tax code you deserve.

While politicians wrestle with taxes, the Federal Reserve often has to adjust its monetary to policy to what it sees happening in the halls of Congress. In the next chapter, we look at how the Federal Reserve tries to adapt and keep the banking system on track.

Notes

1. “The Distribution of Household Income and the Middle Class,” Congressional Research Service, November 13, 2012.

2. ADP National Employment Report, various reports.

3. NFIB Research Foundation. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics, various releases and Supplemental Firm Class Size Tables.