In this chapter we present the case for program management as a primary business function within firms that develop products, services, and infrastructure capabilities. In doing so, we evaluate program management on the basis of how it adds value by creating competitive advantages for a company. In creating these advantages, program management itself becomes a source of competitive advantage that a company can use to outplay rivals.

Eight common critical business problems that plague companies today are presented first. Then, explanations about how the program management discipline has been successfully implemented to overcome each of the problems are provided. These explanations encompass the eight elements of the business case for program management. Finally, the value proposition of program management is summarized in the form of advantages, concluding that it is a relevant way to build a great company.

This chapter seeks to help executives in charge of program management, and practicing program and project managers understand the following:

Why a project management-only approach creates business problems when applied in some critical business situations

How program management helps as an integrating mechanism for business-model deployment by aligning execution activities with business strategy

How program management helps tame the fuzzy front end of development by aligning market and technology research

How program management can be used to manage increasing complexity and accelerated time-to-money goals, mitigate business risk, and manage the business's return on development investment

How program management helps a company create a competitive advantage to outplay business rivals

The message of "it's about the business" is repeated throughout this book. Program management is a primary business function that coordinates and aligns the execution work of multiple functions in multiple interdependent projects toward the achievement of a firm's strategic business objectives.

Over the past few decades, companies have invested an enormous amount of time and resources on improving their project management capabilities to gain products, services, or infrastructure development efficiency. Most senior managers within these companies agree that the investment in project management methods, tools, and practices has had a moderate to significant effect on improvement in the planning and execution of development projects. However, many managers and executives whom we have spoken with expressed several significant problems with using a project management-only approach to develop new capabilities in their organizations. The following list describes their concerns:

Lack of business integration: A company's business model deals with whether the revenue, cost, and profit target economics of its strategy demonstrate the viability of the enterprise as a whole.[18] The crucial point then is the realization of strategy. Since we know that only 10 percent of all concocted strategies are realized and 90 percent fail, it is clear that the real difficulty is with the implementation of the strategy, not the development of the strategy.

Implementation of strategy involves many business functions and processes that need to be coordinated and integrated into a synchronized business action that will hit the desired revenue, cost, and profit target. Project management was engineered to be a coordinating and integrating mechanism. The trouble is that project management has become tactically focused on the triple constraints—time, cost, and quality—and many times fails to serve as the business integrator focused on the implementation of strategy.

Misalignment between strategy and execution: In a large number of organizations, a misalignment exists between companies' strategic objectives and the corresponding abilities to effectively identify, manage, and execute the projects targeted to deliver the objectives.[19] There is often a chasm between business objectives and project management activities. Projects may be efficient and "on target" with respect to time, cost, and quality but fail to achieve anticipated business results such as increased market share or increased worker productivity.

Misalignment of market and technology research: A related problem to the issue addressed above is the poor track record of companies successfully and consistently integrating market and technology research to produce compelling concepts that are focused toward the attainment of desired business objectives. The early definition phase of the development life cycle is commonly called the fuzzy front end and is a complex and difficult stage for any company. A firm's ability to successfully identify the right product, service, or infrastructure capability to develop is critical to the future lifeblood of an organization. To frame the problem succinctly, if a company is developing the wrong product, service, or infrastructure solution, it doesn't really matter if the project management processes are efficient and effective.

Poorly managed ROI: With multiple development efforts in various stages at any one time, GMs of business units are unable to manage the investments in all development budgets and resources. This responsibility falls on the project managers. However, most project managers are challenged to adequately manage the business aspects of products, services, or infrastructure development efforts because the bulk of their training and experience focuses on operational execution of projects.

Increasing complexity: Due to the amount of complexity required to meet customer demands for performance, features, and customization, development efforts are often beyond the scope of a single project.[20] The days of stable, slow to evolve designs are a thing of the past. Today, multiple projects with tightly linked activities and deliverables are required to deal with the complexity of solutions demand from customers. This requires the simultaneous management of multiple, highly interdependent projects, which a project management-only approach is challenged to provide.

Slow time to money: Acknowledgement by firms that time to money can be a significant competitive advantage has made historical methods of product, service, or infrastructure development obsolete.[21] The project hand off or waterfall approach in which project management ownership is transferred (or sometimes thrown over the wall) from one functional project team to the next is too slow to gain time to money competitive advantage. A purely concurrent development method in which functional development occurs in parallel is also inefficient because of the high potential for significant rework late in the project. Eventually, the efforts have to synchronize to reach an integrated solution. This synchronization many times occurs just before or in the early part of final validation and testing. When the interfaces between the concurrent development efforts are not properly defined, communicated, or managed, rework is required and time to money advantage is lost.

Unmitigated business risk: Business risk encompasses all unknown and uncertain events that may prevent an enterprise from executing its strategies, meeting its performance goals, and achieving its business objectives. It also includes anything that may negatively impact the well-being of the enterprise itself. Project-oriented risk-management practices, methods, and tools are effective in managing technical risks and providing valuable information for scope, budgets, and schedule trade-off decisions. However, they are not very effective in identifying and managing the greatest threats to the business success of a company. Current project management curriculums often fall short on providing the necessary business skills that project managers need to fully comprehend the link between strategic business objectives and the output of projects. As a result, many project managers do not possess the breadth of knowledge and experience necessary to identify and manage risk across multiple interdependent projects which can threaten the success of the enterprise.

Ineffective global collaboration: The world is flat. This is how Thomas L. Friedman, in his highly acclaimed book titled The World is Flat, describes the phenomenon that began in the 1990s and continues today whereby knowledge work can be digitized, disaggregated, distributed, produced, and reassembled across the globe.[22] The flattening of the world has enabled the remote development of products, services, and infrastructure capabilities, allowing people in countries like India, China, and Russia to participate in knowledge work with partners across the world. This has created a new business model in which horizontal collaboration is required across the globe to remain competitive. However, many companies have historically operated under a silo, or stove-piped, business model, in which horizontal collaboration across the operating functions that make up the stove pipes is foreign, let alone collaboration across the globe. One by one these companies are being forced to adopt a horizontal, cross-functional business model. Most are struggling with this because of a lack of knowledge and required capabilities.

The problems outlined in the last section are business problems.

They are not project execution problems, and the project management-only approach has shown little capacity to solve them. Organizations that have instituted a program management model to develop products, services, or infrastructure capabilities have done so to address some or all of the problems described above. Therefore, program management is meant to be viewed and deployed as a primary business function within the organization.

How do organizations that have deployed a program management model address the business problems described in the previous section? We focus on the answer to this question in the following section by presenting the program management value proposition for each of the business problems and, in the process, building the business case for implementing the program management model within an organization.

A company's business model deals with whether the revenue, cost, and profit (or efficiency, cost, and profit) economics of its strategy demonstrates the viability of the enterprise as a whole. To elaborate, a business model is the mechanism by which a company generates revenue and profits and serves its customers through the deployment of both strategy and implementation. In particular, a business model includes the following elements.[23]

Selecting customers

Acquiring and keeping customers

Creating value for its customers

Presenting to the market through promotion and distribution strategies

Defining and differentiating its products, services, or infrastructure offerings

Defining and managing the tasks to be performed

Utilizing its resources effectively

Capturing profit

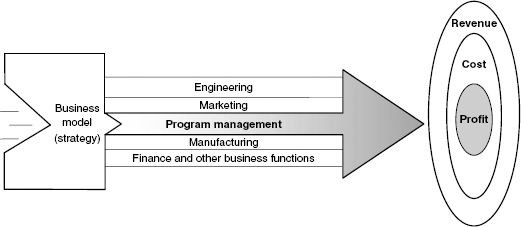

What is the role of program management in the deployment of the business model? Program management is the mechanism by which the work of the various operating functions within a company is integrated to create an effective business model. For example, consider the business functions of marketing, engineering, manufacturing, and finance. Each function has its own language and jargon. For instance, marketing language talks about the four Ps (product, price, place, promotion), finance discusses discounted cash flow, engineering discusses baud rate, and manufacturing is interested in yield. To say that experts from different functions often don't understand one another is an understatement (horror stories about inter-functional misunderstandings abound). A program manager, however, can understand and speak all functional languages.

Program management integrates a company's functions through the use of a PLC that coordinates the functional plans into one synchronized program plan. It integrates all actions into a synchronized program that smoothes out the interfaces between project teams.

Here is what David Churchill, vice president/general manager of Network & Digital Solutions Business Unit for Agilent Technologies, said about the role of program management:

Most firms have the right product ideas, technical talent, and marketing capability to support their business strategies. Organizations many times have difficulty performing to expectations when they cannot turn their strategies into successful execution. Program management is strategic to the firm because it provides the ability to convert business plans into actions that will achieve the intended objectives; it helps bridge the gap between strategy and execution.

Hence, we see program management as a key part of a company's business model. When it is properly conceived and implemented, it helps deploy the business model and execute business strategies to give a business competitive advantage, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

The second aspect of the business case for program management is the alignment of business strategy and operational execution. Many organizations engage in yearly strategic planning activities that focus on the identification of long-range business objectives, as well as high-level plans on how to achieve them. Good strategic management practices identify what an organization wants to achieve (strategic objectives) and how they will be achieved (strategies) over the time horizon, which is typically three to five years. Strategic objectives may include revenue growth, market share increase, decreased cost of goods sold, or technology advancement. For product development companies, strategy consists primarily of a collection of product ideas that, when turned into tangible products, contribute to the achievement of the primary business objectives. For service-oriented companies, strategy consists of a set of services that collectively contribute to the achievement of the business objectives. And for infrastructure development organizations, strategy consists of a suite of infrastructure capabilities that collectively contribute to the attainment of the strategic business objectives.

As we explained in Chapter 1, program management is strategic in nature, but project management is meant to be applied more tactically. Practitioners and researchers have observed that a project management-only approach to development often leads to a misalignment between a company's strategic management process and its output. Plainly stated, the products, services, or infrastructure capabilities that the company delivers may not contribute to the attainment of the strategic objectives that it has targeted. Chapter 3 discusses this identified gap between strategic elements of the development process and project execution.

We view program management as the organizational glue that can translate strategic business objectives into actionable plans that, if managed properly, can be used to achieve the desired business results. The gap between strategic elements and project execution is then effectively eliminated—a clear competitive advantage.

Management teams in successful and innovative companies fully understand that some of the greatest opportunities reside in the fuzzy front end, or definition phase of the PLC.[24] The ability to accurately forecast future customer and market needs and then integrate those needs with leading edge technologies is critical for companies to survive in their respective industries.[25] This work is never simple and the fuzzy front end of product, service, or infrastructure development has served as a test in frustration and a lesson in patience for many. The high failure rates associated with a weak definition have led to negative connotations toward the fuzzy front end.[26] However, this phase is a natural part of every development program and, if managed effectively, can provide great business opportunity and competitive gain. There is no shortcut to creating a strong definition; therefore, companies looking to successfully produce competitive products, services, and infrastructure capabilities on a consistent basis must learn to effectively harness the innovation and research engines involved in the front end of the development process.

The key to realizing the opportunities that the fuzzy front end presents is to "tame" the fluid and ambiguous nature of this phase. This can be accomplished by establishing a framework and well-defined targets to provide focus and employing effective leadership to cut through the ambiguity and competing agendas that characterize the fuzzy front end.[27] The program management model provides both of these things.

To converge on a viable product, service, or infrastructure definition as rapidly as possible, the program manager can establish a framework of targets to be used as motivators and to focus the effort of the cross-discipline team. The targets must concentrate on both time and business. Time-focused targets consist of regularly scheduled review meetings with senior management to demonstrate continued convergence progress in the development of the concept. Business-focused targets include the relevant objectives that drive the need for the solution (for example, time-to-market window, key technologies, and cost targets) and shape the final concept. These targets are the early success criteria that form the basis of the program strategy that provides the guiding direction to achieve business success.

By employing program management principles in the fuzzy front end, an organization will realize the following three key benefits: the leadership necessary to effectively integrate customers, technology, and business perspectives; a framework to enable rapid convergence toward a viable product, service, or infrastructure concept; and a business champion and leader who ensures the product, service, or infrastructure definition fully supports the strategic objectives set forth by senior management.

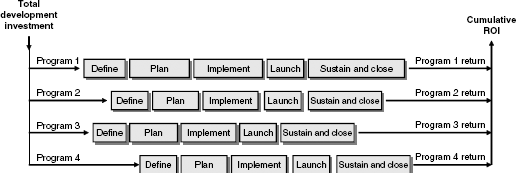

Within a development organization, the general manager makes decisions concerning investments (in the form of products, services and infra- structure) that will help achieve the anticipated business results. The investment normally comes in the form of monetary funding and human and non human resources. The GM nearly always invests in multiple programs that are managed concurrently but with varying life cycles. The total investment budget is divided among the various programs within the organization's development portfolio (see Figure 2.2).

Once a product, service, or infrastructure capability is delivered, it begins generating the intended return (for example, revenue, market share, increased productivity). The cumulative return of each program represents the organization's ROI.

The difficulty and challenge for the GM comes in managing the investment of all development efforts of the organization, in addition to the existing products, services, or infrastructure capabilities already launched and operational. Unless the company is a start-up with a single focus, it is not possible for one GM to manage the business aspects of a development program. He or she must hand this responsibility off to the program manager. In effect, the program manager serves as the GM Proxy for his or her piece of the business investment. A primary role of the program manager, therefore, is to manage the business on the program to ensure the ROI is achieved.[28]

In many aspects of life, humans have a tendency to push the norm or current status quo. Our ever-increasing wants and desires drive our collective environment toward more challenging and exciting ends. This is true in our careers, relationships, activities, and especially in the products and services we utilize.[29] Consumer demand for customized solutions is a continual cycle; once a new product or service becomes status quo, the opportunity arises for a company to develop the next generation solution. This translates into a decrease in a product, service, or infrastructure's life cycle but an increased opportunity for continual refresh. This can keep a company's revenue stream constant and growing, if it continually provides competitive solutions to the markets and customers it serves.

Along with the opportunities described above, the increase in product, service, or infrastructure complexity caused by the demand for customized solutions presents some significant challenges. Complexity in development manifests itself in the following areas: designs have become more complex as features and integrated capabilities increase; the process to develop and manufacture the solutions; the ability to integrate multiple technologies with end user wants; and the current global, multinational approach to development.

Companies that are succeeding in managing these issues are doing the following two key things: adopting a systems approach to development and adopting the program management model to effectively integrate complex solutions. Early adopter companies in the automotive, aerospace, and defense industries continue to utilize the systems and program management approach for their products under development. More recently, companies such as Intel, Tektronix, and Hewlett-Packard have found great success in utilizing systems and platform concepts coupled with the program management model to develop their products, services, and infrastructure capabilities.

Besides demanding increasing complex solutions, consumers also want accelerated delivery of new technologies. It is a well-known fact that in today's highly competitive world, time to money is a critical factor in gaining an advantage over one's competitors. For most companies, gaining time to money advantage means decreasing the cycle time required for developing a product, service, or infrastructure capability. This requires the adoption of new development models. Historically, the two most dominant development approaches were the project hand-off and concurrent methods. A brief overview of each approach is included in the following section, along with an example from the medical product industry that chronicles the company's struggle to find a development model that meets accelerating time to market demand.

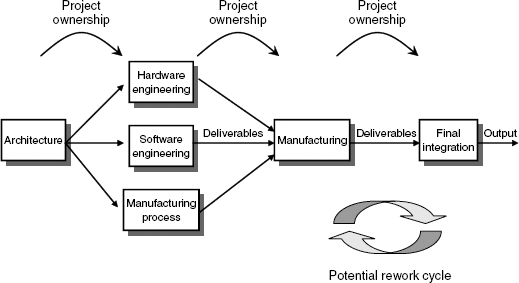

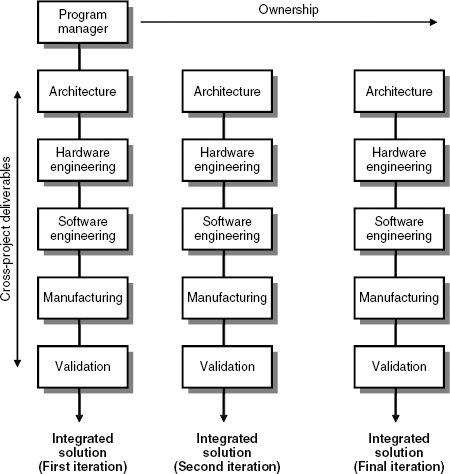

In the project hand-off approach (also called the relay race), each functional team sequentially works on their element of the project, then hands both the work output and project ownership over to the next functional team in line (see box titled, "The Perils of the Project Hand-off Method"). This concept is illustrated in Figure 2.3.

The primary problem with this approach is that the development work accomplished at each hand off occurs within a single function. Errors introduced upstream have to be reconciled downstream, resulting in multiple rework cycles that consume time to money advantage.

The concurrent development method was created to decrease cycle time—an improvement over the project hand-off method.[30] It involves the various functional teams working simultaneously to deliver their elements of the product, service, or infrastructure capability under development (see Figure 2.4). The concurrent development approach, however, has been found to be less than optimal in reducing development cycle time because of what we call the "big bang event" that inevitably has to occur in concurrent development.

The big bang occurs when the concurrently developed elements are integrated. Great inefficiencies can occur due to rework caused by poor requirements definition, lack of change management in the functional development efforts, poor communication between the concurrent development teams, and so on. As a result, it is common for development teams to spend as much or more time performing integration and testing as on concurrent development of the elements (see box titled, "Little Gain with Concurrent Development"). Depending on the extent of any misalignment of the functional outputs being developed, the concurrent method may actually lead to an increase in cycle time over a hand-off approach.

So the question becomes how do companies achieve a significant reduction in development cycle time? The best in-class companies that we've seen, worked for, and have been engaged with accomplish it through an integrated development approach, which is driven by a true program manager.

In the integrated approach, the cross-discipline teams work shoulder to shoulder through the development life cycle, from conception to end of life. The work of each team is coordinated with and reinforced by the work of the other teams. To increase the probability of time-to-money efficiencies, the historically back-end functional activities such as manufacturing, validation, and testing are pulled forward in the development life cycle. Additionally, the front-end activities such as architecture and marketing are involved longer in the development cycle to ensure seamless integration. The big bang phenomenon of integration is replaced by continuous, iterative-design, develop, and integrate cycles (Figure 2.5). The work of all functions involved in the development effort is comprehended in the concept, business case, implementation plan, implementation activities, launch, and support activities. The integrated team takes responsibility for joint consideration of alternatives, decisions that will have consequences to multiple functions, and ownership of the success of the development program.

For the integrated development process to achieve its full potential, the cross-project, multi-discipline team is led by a program manager who can work across the disciplines to ensure their work is indeed fully integrated and aligned to the business objectives. Achieving time-to-money advantage requires tight management of the interfaces, shared risks, and open communication channels between the teams. This involves orchestrating, coordinating, and directing the work of the various functional teams. The program manager brings the required general management, business, and leadership skills required to effectively lead the integrated, cross-project development team (see box titled, "Applying Integrated Development").

Informed risk-taking can provide a means to gain competitive advantage. However, risk taking does not mean taking chances. It involves understanding the risk/reward ratio and then managing the risks, or uncertainties, that are involved in each development effort. Failure to understand the business risk involved can lead to substantial loss for the enterprise. As the business champion for the program, the program manager is responsible for managing business risk.

Good risk management practices allow program teams to move from concept to launch as quickly as possible by removing potential barriers well ahead of the point in which they become impediments to time-to-money goals.[31] To be successful, the program manager must manage risk across multiple, interdependent projects. This requires a different perspective and technique than managing risk for a single project (see Chapter 8); if one of the projects fails, the entire program will likely fail.

The flattening of the world has created opportunities for companies that have learned to take advantage of this new phenomenon. It enables complex systems to be broken down into specialties that are then worked on, reassembled, and integrated into a total solution.[32] Additionally, a company can now take advantage of worldwide resources and alternative methods (such as open-source development) to develop the various elements of the total solution.

However, many of the companies that have adopted forms of distributed horizontal collaboration are struggling to manage the work that takes place around the globe and the clock. Companies that utilize a program management model are consistently succeeding in the management of distributed development efforts that employ outsourcing, open sourcing, in sourcing, and offshoring. The reason? It takes a special type of business model and skill to mold the work of specialists through a high degree of horizontal collaboration to create an integrated solution. As explained in Chapter 1, this is exactly why program management was developed as a business model in the defense and military industries several decades ago—to integrate the work of highly skilled specialists to create and deliver a holistic, complex solution.

The essence of business strategy lies in creating competitive advantages to outplay rivals.[33] Companies have successfully deployed program management to address and resolve the business problems identified in the previous sections. In doing so, they have created competitive advantages over their business rivals who have not deployed program management. To emphasize this point, we evaluate the elements of the program management business case from this perspective:

Integrating the business model elements: Program management is the mechanism by which the work of various operating functions within a company is integrated to create an effective business model. When program management is properly conceived and executed, it helps deploy the business model and strategies much more effectively than an uncoordinated or ad hoc approach.

Therefore, rivals can be outplayed in the long run by a company's ability to execute accurately, timely, and repeatedly through program management practices that integrate and synchronize the work of the operating functions, while focusing on intended business objectives. Program management is very effective in breaking down the functional barriers that can prevent efficient product, service, or infrastructure development.

Aligning business strategy to execution: A company that translates good strategy into successful programs and execution is bound to outplay a rival that has only good strategy. Program management can be viewed as the organizational glue that translates strategic business objectives into actionable plans and then manages the tactics to achieve the desired results. When the program management model is implemented, the gap between strategic elements and project execution is effectively eliminated and the company gains a clear competitive advantage.

Taming the fuzzy front end: The inability of companies to control the fuzzy front end of products, services, or infrastructure development has contributed to a high rate of failure for many development endeavors. However, if managed correctly by employing sound program management practices, the fuzzy front can lead to great opportunity and competitive gain for a business. Program management can establish a sound framework within the fuzzy front end to project accurate forecasts of future customer and market needs and then integrate those needs with leading edge technologies, which creates competitive challenges for business rivals.

Managing ROI: Once a product is launched into the market, or a service or infrastructure capability goes live, it begins generating the return intended. The cumulative return of each product, service, or infrastructure capability represents the organization's ROI. A skilled and competent program manager is the primary business manager for a program and is responsible for focusing on and ensuring that the ROI is met. Program management practices put a continual focus on the business aspects of developing products, services, and infrastructures that lead to better use of investment resources.

Managing complexity: Program management was originally conceived for managing highly-complex development undertakings. It puts a systems structure in place and provides a framework which disaggregates the complexity into manageable elements. By contrast, companies not employing program management practices can and do become consumed by the complexity.

Accelerating time to money: By using an integrated development approach that is driven by the program management function, time-to-money goals are optimized. The program management model is built on the development, management, and delivery of interdependencies between the functional elements of the program throughout the development life cycle. By incorporating and managing the cross-project deliverables through an iterative and integrated development process, a limited rework scenario develops. This translates to faster time-to-money possibilities—an advantage that brings an extended sales cycle, premium prices, higher profits, and faster learning over companies that do not use program management practices.[34]

One company leader we talked with who agrees with this assessment is Gary Rosen, vice president of Engineering for Varian Semiconductor Equipment. Rosen describes the role of program management in accelerating time to money:

If you have a strong program management function, products are closer to what the customers want, and the team spends less time iterating late in the program to meet customer expectations. A program manager adds clarity for the engineering team by balancing market requests with engineering capabilities', therefore, setting realistic customer targets. This results in more efficient use of resources, which allows a program team to deliver what the customer wants the first time and then move on to the next product development program.

Mitigating business risk: Risk taking is necessary in many industries, if a company is intent on being a market leader. Products, services, or infrastructure capabilities that don't push the risk envelope probably aren't worth the development investment required—unless the company is intent on being a market follower, which is a valid strategy for many companies. Market leaders understand they must run directly toward risk to put distance between themselves and their competitors.

Program risk management methods flush out the business risk involved in a development program, then effectively manage the risk at both the program and project level to maximize the reward/risk ratio.

Navigating the flat world: Companies that utilize a program management model for product, service, or infrastructure development have succeeded in managing highly distributed development efforts that the flattening of the world has made possible. These companies are now able to take full advantage of worldwide specialty resources by effectively managing the horizontal collaboration between the multiple project specialists that are highly dispersed.

Now, back to the question: Can program management be a competitive advantage? We believe that the eight elements of the business case for program management prove that the answer to this question is a resounding yes.

Even though companies have invested an enormous amount of time, money, and resources trying to improve their operational and project management capabilities, many of these companies still face serious problems associated with their development process. The most serious ones identified include the following: misalignment between strategy and execution, poorly managed ROI of development dollars, increasing complexity of design and process, and slow time to money. The program management model is an effective approach companies use to confront these business problems in the development of their products, services, and infrastructure capabilities.

This chapter reviews the following eight elements of the business case for program management: integrating business model elements, aligning business strategy and execution, taming the fuzzy front end, managing ROI, managing complexity, accelerating time to money, mitigating business risk, and navigating the world. These eight elements of the business case for program management create a competitive advantage for companies that employ them. In many instances, they are the "secret sauce" that helps a company transition from good to great.

[18] Thompson, J., Arthur A. and A. J. Strickland III. Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases, 13 ed. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2002.

[19] Morris, P. W. G. and A. Jamieson "Moving from Corporate Strategy to Project Strategy." Project Management Journal 36(4), 2005: 5–18.

[20] Cleland, David I. Field Guide to Project Management, 1st edition. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1998.

[21] Smith, Preston G. and Donald G. Rinertsen. Developing Products in Half the Time: New Rules, New Tools, 2nd edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

[22] Friedman, Thomas L. The World is Flat. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux Publishing, 2006, pp. 439–440.

[23] Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: Wikipedia, (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Business_model):

[24] Smith, Preston G. and Donald G. Rinertsen. Developing Products in Half the Time: New Rules, New Tools, 2nd edition: Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

[25] Koen, P. A., G. M. Ajamian, et al. (2002). Fuzzy front end: Effective methods, Tools, and Techniques. The PDMA Tool Book for New Product Development. P. Belliveau, A. Griffin and S. Somermeyer. New York NY: John Wiley & Sons: 5–35.

[26] Cooper, Robert G. Winning at New Products: Accelerating the Process from Idea to Launch, 3 ed. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books, 2001.

[27] Martinelli, Russ. "Taming the Fuzzy Front End." Project Management World Today (July–August 2003).

[28] Martinelli, Russ and Jim Waddell. "Program Manager Roles, Responsibilities and Core Competencies."Project Management World Today(November–December 2004).

[29] Gharajedaghi, Jamshid. Systems Thinking: Managing Chaos and Complexity. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinmann Publishing, 1999.

[30] Thamhain, Hans. J. Management of Technology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

[31] Martinelli, R. and Jim Waddell. "Managing Program Risk." Project Management World Today(September–October 2004).

[32] Friedman, Thomas L. The World is Flat. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux Publishing, 2005, pp. 439–440.

[33] Hamel, Gary and C. K. Prahalad. Competing for the Future: Breakthrough Strategies for Seizing Control of your Industry and Creating the Markets of Tomorrow. Harvard Business School Press, 1994.

[34] Morris, P. W. G. and A. Jamieson Moving from Corporate Strategy to Project Strategy. Project Management Journal 36(4), 2005: 5–18.