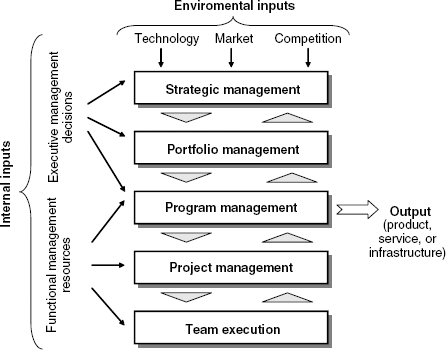

Historically, the primary managerial functions and processes of product, service, or infrastructure development have been defined and viewed as independent entities, each with its own purpose and set of activities. For example, executive management normally performs the strategic processes that set the course of action for the organization. Portfolio management and project selection are commonly thought of as senior and middle management responsibilities. Program planning and execution processes are performed by the program manager and core team, while project managers and team leaders are responsible for project planning and execution processes. Each of these functions and processes is executed separately by a different set of people within the organization. At best, the strategic element feeds the portfolio element, the portfolio element feeds the program management element, and the program management element feeds the projects and team execution that delivers the products, services, or infrastructure outputs. In many cases, this still results in projects that are not tied directly to either the business strategy or the organization's portfolio.

Companies invest much time, money, and human effort into refining and improving each of their independent functions and processes, only to come to the inevitable conclusion that they are not coming any closer to effectively and efficiently turning their ideas into positive business results. Increasingly, this fact is leading business leaders to the realization that their independent variables cannot remain independent. Rather, they must be transformed into a set of interdependent elements that form a coherent development system.

This chapter uses the systems concept to explain and demonstrate how program management, and other critical managerial functions and processes within an organization, must be defined and executed as elements of an integrated management system. It explains how an organization can be viewed as a holistic, coherent system that is composed of critical managerial elements and processes. In doing so, this chapter will help senior executives, program managers, and project managers accomplish the following:

Build an integrated management system model

Deploy the strategic and tactical elements of the integrated management system

Effectively align the strategic and tactical elements of the integrated management system

By taking a systems approach through an integrated development model, an organization can realize improved business alignment between execution output and business strategy. As we demonstrate in this chapter, the program management discipline plays a pivotal role in aligning the tactical work output of multiple project teams with the mission and strategy of an enterprise.

We define a system as an assemblage of interrelated elements or subsystems comprising a unified whole. It can be visualized as a simple entity consisting of four primary elements: inputs, output, interdependent subsystems, and an environment within which the system operates. Figure 3.1 illustrates the generic systems model.

The nature of the system elements are unique to each problem that the system resolves. The subsystems are highly interactive and interdependent on one another. The role of the subsystems is to utilize the inputs provided by the environment to produce a desired output. Both the inputs and the output are heavily influenced by the particular environment within which the system exists.

When one looks at an entire business from a systems perspective, a holistic view of the enterprise emerges. Within the business enterprise system, key subsystems such as the corporate mission, strategic objectives, organizational functions, organizational structure, critical processes, and programs exist to effectively and efficiently convert the business inputs into the desired outputs—technological advantage, cost value leadership, or profits. Like any system, the subsystems are highly interdependent upon one another. For example, the mission of the business enterprise influences the strategic business objectives defined; moreover, the objectives define the functions that are needed to achieve the objectives, as well as how the enterprise is organized. The strategic objectives, functions, and organizational structure all have a direct influence on the selection of the critical processes and tactics utilized to convert inputs to outputs.

Finally, the business enterprise operates within, and is influenced by, a dynamic environment. Examples of environmental factors that have an impact on the mission, structure, operation, and output of the business enterprise system include shareholder expectations, domestic and world economic conditions, technology trends, customer usage models, and competitor actions.

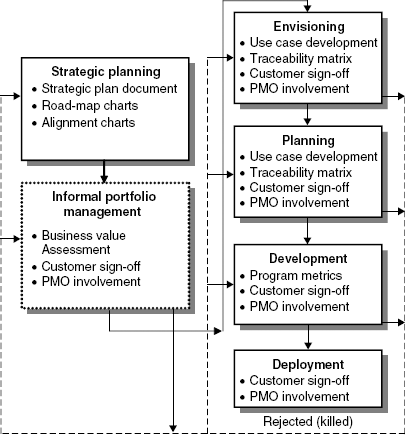

The heart and engine of growth for the business enterprise system is the development component that consists of the management functions and critical processes needed to convert inputs into an output.[35] We refer to the set of functions and critical processes as the integrated management system. The integrated management system, shown in Figure 3.2, is the mechanism from which new products, services, or infrastructures are conceived and developed to realize the mission and strategic objectives of the business.[36]

It is common practice to view the primary subsystems of the integrated management system within a business as independent entities, each with its own set of activities, processes, and tools. Additionally, in practice, there tends to be a real separation between the strategic and tactical subsystems of the development system. This leads to misalignment between the business objectives and the work output of the organization, which may result in an unfulfilled mission and strategic objectives (see box titled, Three Beer Drinkers as a System).

Contrary to this common practice, it is important to view the integrated management system as a collection of interdependent subsystems. In doing so, a holistic perspective to product, service, or infrastructure development becomes possible. Among the advantages in viewing the functions as an integrated system—instead of a set of loosely dependent elements—is that the system becomes more flexible and receptive to improvement when an organization is looking to gain additional efficiencies. By taking the ad hoc approach, an organization finds itself chasing and attempting to cure a set of symptoms, instead of taking a systems approach that will most likely lead to root-cause analysis and cure of overriding problems.

This is analogous to actions one may take if his or her automobile is performing poorly and exhibiting problems such as fuel inefficiency or rough idling. By taking an ad hoc approach to the problem, one may try to treat the poor fuel efficiency by adding an oxidization additive or replacing the filter. To treat the poor idling problem, one may change the spark plugs or adjust the engine timing. Any or all of these actions may yield an improved performance for a period of time, but they will not solve the root problem if the automobile is in need of an overall tune-up. By viewing the engine and ignition functions of the automobile as a system, a holistic approach to diagnosing and resolving the root problems becomes possible.

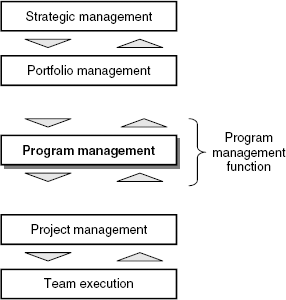

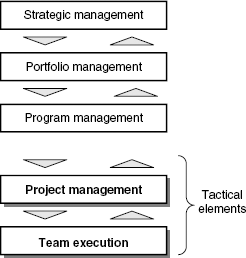

The subsystems of the integrated management system are categorized into the following three types: the strategic subsystem, the tactical subsystem, and the program management subsystem. The strategic subsystem consists of the strategic management and portfolio management processes. The tactical subsystem includes the project management and team management functions. The program management subsystem is the organizational glue that translates strategy into actionable plans and tactics that achieve the desired business results. The following sections will look at each of the three subsystems that make up the integrated management system.

The strategic subsystem of the integrated management system is comprised of two primary processes normally performed by the senior management team of an organization—strategic management and portfolio management (see Figure 3.3).

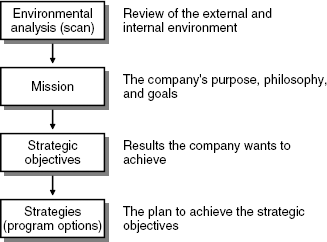

The strategic management process involves definition of the company mission, analysis of the internal and external environment, identification of the strategic objectives, and definition of strategic options to fulfill the objectives. The portfolio management process includes the review and selection of the strategic options that will be implemented and also evaluates the success of the current process. The following sections explore the strategic and portfolio management elements of the strategic subsystem in detail.

Strategic management is defined as a set of decisions and actions that result in the formation and implementation of plans designed to achieve a company's objectives.[37] It includes the following three primary elements: the business mission, strategic objectives, and strategy. The mission statement is a broadly framed statement of intent that describes why the company exists in terms of its purpose, philosophy, and goals. Strategic objectives define what the business wants to achieve over a specific time horizon, which is typically three to five years. Strategy is the business's game plan that reflects how it will accomplish the objectives. It is imperative that all three elements of strategic management be in place to properly frame the direction of the organization. Figure 3.4 shows a generic strategic management process flow.

Understanding the current and future environment that the firm will be operating in is critical to the strategic management process. The senior management team must have a comprehensive knowledge of the following: the future direction of the economy in the company's market, the impact of potential technological breakthroughs, local and foreign political climates of countries in which it operates or wishes to operate, the size and stability of its supplier base, and the firm's own resource capability and limitations. This knowledge of the current and future state of the external and internal environments will influence the company's marketing scheme, as well as its choice of strategic objectives and strategies.

Some have argued that a company mission is of little use because big visions are rarely realized.[38] However, without a mission, a company lacks the overriding statement of purpose for the business; its philosophy toward its customers, employees, and competitors; and its goals such as survival, growth, and profitability. Most importantly, without a mission, there is no basis to judge the relevancy of opportunities, threats, and program options presented to a company's management team. All possibilities would have equal value.

In our view, defining the company mission is perhaps one of the most important responsibilities of the senior management team. The mission statement defines why the business exists, what the strategic intent of the company is, what its core values are, and how the management team measures success. The company mission statement should be designed to accomplish several outcomes, as follows:

Ensure that everyone within the organization understands the company purpose

Provide the basis for allocating the organization's resources

Establish the guidance to translate company objectives into programs, projects, and work elements

Specify the means for which attainment of company objectives can be assessed and assets controlled.

The mission statement should describe the company's products, markets, and technological areas of emphasis in a way that demonstrates the values, priorities, and goals of the management team.[39] For most companies, financial and economic goals greatly influence the strategic direction of the enterprise. This may be either explicitly or implicitly stated in the company mission statement. Take, for example, these two mission statements. The first, from Proctor & Gamble, explicitly includes sales and profits as part of its mission statement. The second, from Merck, implicitly implies profit as a superior rate of return.

Here is Proctor & Gamble's mission statement.

We will provide branded products and services of superior quality and value that improve the lives of the world's consumers. As a result, consumers will reward us with leadership sales, profit, and value creation, allowing our people, our shareholders, and the communities in which we live and work to prosper.[40]

Here is Merck's mission statement:

The mission of Merck is to provide society with superior products and services by developing innovations and solutions that improve the quality of life and satisfy customer needs, and to provide employees with meaningful work and advancement opportunities, and investors with a superior rate of return.[41]

A good mission statement promotes a sense of shared expectations among all members of the organization; provides common purpose, direction, and goals for the company; and defines a company's intent for shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, and the community in which it operates.

As stated earlier, the strategic objectives define what the company wants to achieve within a multiyear period. To achieve long-term prosperity, management teams commonly establish strategic objectives in the following seven areas[42]:

Profitability: The ability to survive and achieve a company's other strategic objectives depends greatly on its ability to meet its profitability objectives. Profitability objectives may include increased level of profits, return on assets or investments, and profit growth normally expressed as earnings per share for publicly traded enterprises.

Productivity: These objectives normally focus on how efficient an organization is in creating output from input and may focus on decreasing cost of goods produced, reduced throughput or cycle time, minimization of factory defects, or increased reuse of components or software.

Competitive position: A business's relative dominance in the marketplace as compared to its competitors; it is normally measured in total sales and/or percentage of total market share. Examples of competitive position strategic objectives include increasing market share by one percent per year, increasing yearly sales by opening new markets, or increasing quality to strengthen brand image.

Employee development: Career growth and new opportunities for the employees of the enterprise, primarily to foster the development of future leaders and reduce overall employee turnover.

Employee relations: The purpose is to increase company loyalty and employee productivity; it includes improved working environment and conditions, implementation of rewards and bonuses based on company performance, and consistent access to senior management.

Technology leadership: If a company chooses to position itself as a technology leader, it must establish aggressive objectives to provide technology improvements and changes in its products or services. Objectives may also include investment in improved manufacturing technologies to lower production costs, integration of several discrete technologies into a single solution, or funding research activities to increase security and safety.

Public Responsibility: Businesses have learned that company image translates to brand value. Brand value provides a company the opportunity to charge premium prices—relative to their competitor's—for their products or services. Objectives may include increased adherence to land, water, and air contamination to decrease pollutants, increased funding for community charities and public education programs, and sponsorship of community activities and events.

It should be pointed out that a business normally does not strive to identify strategic objectives in all seven areas presented above, but rather only in those areas that align with and fully support attainment of the corporate mission. Additionally, strategic objectives should possess a number of attributes for effectiveness. A strategic objective must be specific in nature by stating what will be achieved, when it will be achieved, and how it will be measured. An objective must be challenging enough to raise the bar on corporate performance but attainable to prevent employee frustration and lack of motivation. Finally, it must be flexible to adapt to changes in the organization's operating environment.

Strategy defines how a business will achieve the strategic objectives it has established. Strategy consists of the portfolio of ideas that, when fully developed, will contribute to the attainment of the strategic objectives[43]. Superior products, services, and infrastructure capabilities are the means to build technology leadership advantage over competitors, expand market share, increase revenue, decrease operating costs, and strengthen brand value (see box titled, "If You Don't Know Where You're Going, any Road Will Get You There").

To be credible and achievable, the organization must manifest the various strategies into programs that the company intends to fund and resource. The sum of the program outputs will provide the combined means to achieve the desired objectives. Business, technology, and market strategies must culminate in a program strategy to be executed.

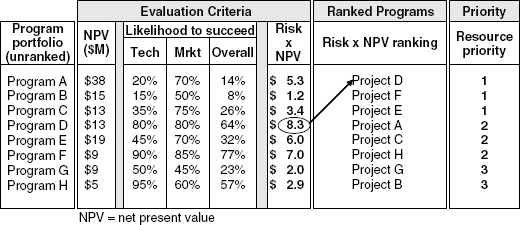

The second strategic element of the integrated management system is the portfolio management process. Portfolio management is defined as a dynamic decision process, whereby a business's list of active programs is constantly updated and revised.[44] As is usually the case, organizations have many more products, services, or infrastructure ideas than available resources to execute them. As a result, resources become overcommitted, and an organization must find a way to broker competing demands for its limited resources. Portfolio management is an effective process for identifying and prioritizing products, services, or infrastructure programs that best support attainment of the strategic objectives. Programs are ranked and prioritized based upon a set of criteria that represents value to the customer and the organization. Resources are then assigned to the highest value and most strategically significant programs. Low-value programs must be cut, returned for redefinition, or put on hold until adequate resources are available.

According to the model developed by Cooper, Edgett, and Kleinschmidt, the three fundamental principles of portfolio management are as follows: maximize the value of the portfolio of programs in terms of company objectives, achieve a balance of programs based upon a number of vectors, and establish a strong link between the portfolio and organizational strategy. Accomplishing these principles should also result in matching the number of selected programs with the available resources. This is sometimes referred to as resource capacity planning.

The foundation for an effective portfolio management process is based on the ability of the management team to determine the factors that constitute program value for their organization. The team must also establish a prioritization system to evaluate one program against the others. Once it gets beyond this hurdle, which is sometimes monumental, the organization will have accomplished the following two things: a real understanding of how value is defined and a prioritized portfolio of programs that clearly differentiates between those that provide the most and least value to the business. Thus, maximization of the portfolio is established. The punch line of portfolio management is now possible. The management team can allocate and concentrate its resources to the programs that provide the most value to the organization', therefore, achieving maximum output from a limited input.

Figure 3.5 is an example of a prioritized portfolio of programs from a manufacturer of Internet communication products. Resource allocation occurred in priority order, with priority one programs receiving full allocation of resources, priority two programs receiving full allocation of resources once priority one programs are fully staffed, and priority three programs receiving full resources once priorities one and two programs are fully staffed.

Creating a balanced portfolio involves making thoughtful decisions at the macro level about which types of programs the company chooses to invest in and the levels of investment. This is analogous to the decisions one makes concerning personal financial portfolios. One decides which types of investment to make (for example, stocks, bond, mutual funds, cash, and so on) and at what percentage. Similarly, companies decide which programs to invest in—platforms, new products, iterations, and research—and at what percentage (see Figure 3.6). The objective is to balance investment so that both the current and future value propositions to customers are secured and the strategic objectives of the company are funded.

The investment buckets approach to balancing a portfolio is the most common method we have seen in our experience. The selection and structure of the investment buckets are unique to each business and are highly influenced by a company's strategic objectives, market segmentation, and product, service, or infrastructure types. Cooper, Edgett, and Kleinschmidt offer seven possible dimensions of how to define an organization's investment buckets, or portfolios, as follows:[45]

Strategic objectives

Product line

Market segment

Technology type or platform

Program or project type

Familiarity matrix

Geographical region

A financial industry software company we worked with, for example, defines its investment buckets from a strategic standpoint. Its portfolio structure was established on the basis of funding the company's mission. The mission was defined as follows: Drive material impact on (our) margin, growth, and influence by bringing to market software solutions and services and delivering and influencing technologies that enhance the value of (our) platforms. The investment buckets (or portfolio of programs) and allocated funding levels for this organization are shown in Figure 3.7.

Balancing the portfolio achieves the following two primary things for the business: It allocates funding based on strategic intent, and it dedicates funding and resources to specific portfolios. As a result, the company's strategic objectives are adequately funded in priority order, and resources are focused within the investment buckets defined, eliminating cross-portfolio resource contention.

The third principle of portfolio management establishes the fundamental imperative that resource allocation must be driven by strategic intent. Strategic objectives must influence how the company spends its investment money, which is normally in the form of a research and development (R&D) budget. As Cooper et al. so eloquently explains, "Well meaning words on a strategy document or mission statement are meaningless without the funding and resource commitments to back them up."[46]

Ensuring strategic intent can be accomplished through implementation methods for maximizing the value of the portfolio and establishing balance. When strategic elements are included in the program prioritization criteria, the value of each program becomes apparent and the results are greater. Also, by utilizing strategic objectives and the mission to define the investment buckets of the enterprise, the overall structure of a company's portfolio solution becomes aligned to its strategic objectives. Then, by allocation of funds and resources to the investment buckets, an organization can be confident that its resources are assigned to programs that provide the greatest strategic value.

Executing good decisions that give the portfolio a robust set of programs that reinforce the business strategy requires strong leadership from executive management. Executives must ensure that the process is effective and that, at the end of the day, the tough choices are made. Without strong leadership, an organization will continue to overcommit its resources and underachieve attainment of its strategic objectives. The box titled, "Do You Agree with This Portfolio Verdict?" is an example of such a scenario.

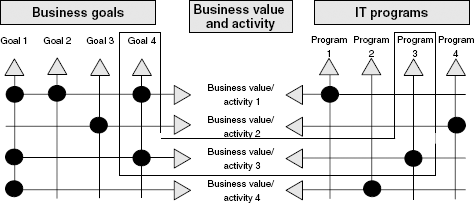

At the heart of the integrated management system is the program management function, as shown in Figure 3.8.

The program manager does not create the mission or strategic objectives. This is the role of senior management. The program manager does not plan and execute the project deliverables. This is the role of the project managers and project team members. The program manager does ensure the attainment of the value proposition identified by the portfolio management process by delivering an integrated solution through the collaboration and coordination of multiple interdependent projects. If the value proposition is attained, alignment between business strategy and project execution is achieved.

So then, what does it mean to say a company's programs are aligned with its business strategy? What elements of program management align to which elements of business strategy? And, how do you align them? The following section addresses these questions.

First, what is alignment? Alignment is the degree to which priorities of an organization's program management practices are compatible with that of its business strategy. Second, what gets aligned? The focus and content of the program management elements are aligned within attributes of the business strategy. Let's first determine what the program management elements are and then define their focus, content, and attributes.

These following six elements make up the program management subsystem:

Strategy

Organization

Processes

Tools

Metrics

Culture

Program strategy is defined as the approach, position, and guidelines of what to do and how to do it to achieve the highest competitive advantage and the best value from the program.[47] As previously mentioned, business, technology, and market strategies must culminate in a program strategy to be executed, as illustrated in Figure 3.9.

The program strategy manifests itself into four important elements of the program:

The product, service, or infrastructure definition

The program business case

The program success criteria

The integrated program plan

Every development program relates to a product, service, or infrastructure capability. The development process begins with ideas and conceptualization. Developing the product, service, or infrastructure definition includes synthesizing end user, technology, and market research to establish a conceptual idea to address the business, technology, and market strategies of the organization. These elements are instantiated in the definition.

The business case is the most vital part of the strategy. It establishes the degree of likelihood that the concept will help to achieve the strategic objectives of the organization. It spells out rationale as to why the customer will buy or use the product, service, or infrastructure capability and what makes it better than other alternatives. The business case also presents the competitive advantage. For example, the advantage may be a combination of product attributes, functionality, performance, and quality.

The program success criteria establishes the business criteria with which to define and measure program success, and, in effect, set the tactical targets to achieve the strategic objectives. The criteria makes it clear in advance how the program results be evaluated. Success and failure criteria will be outlined in detail and the different success dimensions will be judged, such as business, technology, cost, and timing. The business perspective is the dominate criteria that, depending on the type of program, may include the growth pattern of sales, market share, profitability, or increased worker productivity during a period of several years.

The integrated program plan sets the program scope and defines how the objectives will be obtained via the delivery of a product, service, or infrastructure capability. Scope defines the program boundaries, the final deliverables on the program level, and the work that will and will not be done on the program. It also includes an estimated resource profile and overall budget needs. Therefore, the integrated program plan defines the program deliverables and shows the integrated time, resource, and budget needs.

Program organization consists of the structure that is needed to successfully deliver the intended results. The most common error companies make in implementing program management is failing to understand the difference between a program structure and a project structure. Chapter 5 will describe in detail the two critical factors to consider when structuring a program, that is, the structure must support the highly integrated and interdependent nature of the projects within the program, and the structure must support the fundamental elements of team success.

Program processes such as the PLC, schedule management, financial management, risk management, and so on, help to make the operational aspects of the program more efficient and effective (see Chapter 8). Most importantly, program processes help to ensure that the work of the multiple project teams is being managed consistently and in a coordinated manner.

Program metrics (or performance measures) gauge how well the program strategy works, how much progress is being made toward selected goals, or how well programs are performing to date (for example, profitability index and staffing levels).[48],[49],[50],[51] The intent is to focus attention on the business aspects of the program (see Chapter 9).

Program tools are the procedures and techniques that process the data involved in a program and extract the information necessary to determine progress toward achievement of the program objectives and support important program decisions (see Chapters 10 and 11).[52]

Program culture refers to the behavioral norms and expectations shared by members of a program.[53] The essence of culture is to have a sense of identity with the program organization and to accept investing both materially and emotionally in the success of the program (see Chapter 14).[54]

Figure 3.10 illustrates how program management elements should be driven by the business strategy of a company. A company chooses a strategic direction by selecting competitive attributes of its strategy (for example, time to market, quality, cost leadership, or product feature set).

These attributes, in turn, are used to drive the focus and content of the program management elements for a particular program. For example, if the competitive attribute of time to market is chosen, the primary strategic focus of the program becomes schedule driven, and the elements are configured to support this strategy. Examples of program management element configuration used by different companies are shown in Table 3.1.

To extend the alignment process further, the focus and content of the program management elements shape the project management elements of the tactical subsystem of the integrated management system. Project management elements (organization, processes, tools, and culture) must follow the same configuration as the program management elements to gain consistency across the projects. Through this process, systematic alignment between business strategy and tactical execution is achieved.

Table 3.1. Aligning program management elements to strategy

Strategy | Program focus | Program management |

|---|---|---|

Competitive attributes | Content of program management elements (examples) | |

Time to market | Schedule driven | (Strategy) Dropping features if necessary in a trade-off situation, spending additional money to recover projects if they slip |

(Organization) Building a flexible structure to facilitate the speed of project execution | ||

(Process) Overlapping and combining phases, milestones, activities | ||

(Metrics and tools) Focusing on schedule | ||

(Culture) Building schedule-oriented program culture (for example, rewarded speed) | ||

Superior quality | Quality driven | (Strategy) Delaying schedule if necessary in a trade-off situation |

(Organization) Building a flexible structure to ensure the quality level of the product | ||

(Process) Having a sequential, iterative process | ||

(Metrics and tools) Focusing on scope/risk | ||

(Culture) Building quality-oriented program culture (for example, rewarded quality) | ||

Cost reduction | Process-improvement driven | (Strategy) Focusing on process improvement |

(Organization) Having a flexible structure and adapting it to changes in process improvement, with the ultimate goal of saving costs | ||

(Process) Having a standardized process with templates | ||

(Metrics and tools) Focusing on schedule/cost | ||

(Culture) Building cost-oriented program culture (for example, rewarded cost) | ||

Innovative feature and cost | Feature and cost driven | (Strategy) Focusing on features with the major concerns of program cost and schedule |

(Organization) Having a flexible structure to ensure the innovative features at minimum cost | ||

(Process) Having a standardized but flexible process | ||

(Metrics and tools) Emphasizing feature tracking and cost | ||

(Culture) Building an innovative and cost-oriented program culture (for example, rewarded innovation) | ||

Superior quality and cost | Quality and cost driven | (Strategy) Focusing on quality with the major concerns of cost and schedule (Organization) Having a flexible structure to ensure the best quality at minimum cost |

(Process) Having a standardized process with the aim of minimizing cost and ensuring superior quality and service | ||

(Metrics and tools) Focusing on quality, cost, and schedule | ||

(Culture) Building quality- and cost-oriented program culture (for example, rewarded quality and cost) | ||

Science and cost | Science and cost driven | (Strategy) Focusing on science with the major concerns of cost |

(Organization) Involving technical teams to ensure that the science goals are met at minimum cost | ||

(Process) Having standard guidelines with the aim of checking that the science goals are met within the expected cost | ||

(Metrics and tools) Focusing on technical, cost, and schedule | ||

(Culture) Building science- and cost-oriented program culture (for example, rewarded science goals) |

However, once a company achieves alignment between strategy and tactics, it does not mean that it no longer has to focus attention on the alignment. The focus and content of the program strategy, as well as the program organization, processes, metrics, tools, and culture, need to be periodically reviewed and checked against the competitive attributes and strategy of the business.

The operating conditions (the actual conditions of program implementation) may or may not be the same as those assumed in the planning phase of the program because of changes in the environment. The actual operating conditions may differ significantly from the original (or intended) business strategy and need to be changed to remain realistic. This process provides strategic feedback and helps a new strategy emerge.[55] An example of what can happen when this step is not followed is provided in the box titled, "Asleep at the Wheel."

Tactical elements of the integrated management system include project management and team execution, as illustrated in Figure 3.11 Project management and team execution form the basis for planning, implementing, and delivering the interdependent elements of products, services, or infrastructure capabilities.

This is where the real hands-on work gets completed. The functional project managers are responsible for the detailed planning and execution of the deliverables pertaining to their respective operating functions (for example, hardware engineering, software engineering, and marketing). Each functional project manager, along with his or her respective team members, develops a specific project plan and schedule. The results of this planning will be further refined and combined between the program manager and the functional project managers for the overall program. They will ensure that all of the interdependencies, gaps, and overlaps are appropriately addressed and integrated into the master program plan. Once the program plan is approved, each project team executes their part within the program structure, with the oversight of the program manager.

Project management and team execution are the subjects of volumes of books. Thus, we will not attempt to summarize the details of project planning and execution in this book. However, the key differences between project management of an independent project versus one within a program are worth noting. The projects within a program are highly interdependent; therefore, a significant amount of cross-project collaboration is required of the project managers. Obviously, this is not the case for independent projects. Additionally, project managers for a program are directed by a program manager who has full responsibility, authority, and accountability for the success of it and all the projects.

Program management is an effective means to bridge the chasm between organizational strategies and project execution. It is a core business function that integrates the work of multiple project teams and focuses that work on the attainment of the company goals. Throughout the development life cycle, program management methods measure the work output against the goals of the organization.

A company that has good business strategy, programs, and execution is bound to outplay a rival that has good strategy but cannot execute. Effective use of the program management element of an integrated management system creates a competitive advantage.

Gary Rosen, vice president of engineering for Varian Semiconductor Equipment, describes the competitive advantage of program management in the following way:

Good program management goes right to the bottom line, it improves a company's P&L (profit and loss). A company that delivers more products, better products, and does so faster wins the competitive race. Program management makes better, faster, and cheaper a reality.

Program management as a business function has a central role in aligning programs with business strategies. The role of program management is the mechanism from which new products, services, or infrastructure are conceived and developed to realize the mission and strategic objectives of the business. The integrated management system includes the following three subsystems: strategic, program management, and tactical.

The strategic subsystem, including strategic management and portfolio management, concocts the business strategy, clearly identifies the strategy's competitive attributes, and chooses a set of programs to accomplish the strategy. The program management subsystem elements (program strategy, organization, process, tools, metrics, and culture) are then aligned with the competitive attributes of the business strategy. Lastly, the tactical subsystem, including project management and team execution, is aligned to business strategy through the program strategy and master program plan.

Program management links and aligns the projects within a program to the business strategy of the company. This enables a company to consistently execute its strategy and create a competitive advantage over its rivals.

[35] Bowen, H.K, Clark, K.B, Holloway, C.A, Wheelwright, S.C. Development projects: The Engine of Renewal. Harvard Business Review 72(3), 1994, pp. 110–120.

[36] Martinelli, Russ and Jim Waddell. "Aligning Program Management to Business Strategy". Project Management World Today (January-February 2005).

[37] Pearce II, John A. and Richard B, Robinson Jr. Strategic Management: Formulation, Implementation, and Control, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

[38] Gharajedaghi, Jamshid. Systems Thinking: Managing Chaos and Complexity. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinmann Publishing, 1999.

[39] King, William R. and Cleland, David L, Strategic Planning and Policy, New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1978.

[40] Proctor & Gamble website, http://www.pg.com

[41] Merck Website, http://www.merck.com

[42] Pearce II, John A. and Richard B. Robinson. Strategic Management: Formulation, Implementation, and Control, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000: pp. 241–244.

[43] Martinelli, Russ and Jim Waddell, "Aligning Program Management to Business Strategy", Project Management World Today (January-February 2005).

[44] Cooper, Robert G, Edget, Scott J. and Kleinschmidt, Elko J, Portfolio Management for New Products. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing, 2001: pp. 3.

[45] Cooper, Robert G, Edget, Scott J. and Kleinschmidt, Elko J, Portfolio Management for New Products. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing, 2001: pp. 87–88.

[46] Cooper, Robert G, Edget, Scott J. and Kleinschmidt, Elko J, Portfolio Management for New Products. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing, 2001: pp. 140–141.

[47] Poli, M. and Shenhar, A.J, Project Strategy: The Key to Project Success. in Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology. Portland, OR: PICMET 2003.

[48] Milosevic, D.Z, Inman, L. and Ozbay, A, "Impact of Project Management Standardization on Project Effectiveness", Engineering Management Journal, 2001. 13 (4): 9–16

[49] Tipping, J.W, Zeffren, E. and Fusfeld, A.R. "Assessing the Value of Your Technology". Research Technology Management, 1995. 38(5): 22–39.

[50] Major, J, Pellegrin, J.F. and Pittler, A.W, "Meeting the Software Challenge: Strategy for Competitive Success". Research Technology Management, 1998. 41(1): 48–56.

[51] Nicholas, John, M, Managing Business and Engineering Projects: Concepts and Implementation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1990.

[52] Aronson, Z.H, et al. "Project Spirit—A Strategic Concept". Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology. Portland, OR: 2001.

[53] Graham, Robert J. and Randall L. Englund. Creating and Environment for Successful Projects. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1997.

[54] Shenhar, Aaron, Strategic Project Management: The New Framework. PICMET, 1999

[55] Mintzberg, Henry, The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. New York, NY: The Free Press, 1994.