TO STAY COMPLIANT WITH REGULATIONS first means you must interpret the regulation. You must understand the gap between the regulation and your organization. The next step is coming up with a plan. Finally, you must execute the plan and implement measures to report compliance.

Without compliance laws and industry regulations, compliance means adhering to an organization's internal policies. However, it is likely that—whatever your industry—compliance laws exist to which you must adhere.

Many industry standards and government regulations affect IT operations. Remember each country has its own laws and regulations. Thus, the number of compliance laws and regulations expands greatly. In this chapter, you will learn about many of the major regulations. Keep in mind that you are only scratching the surface. Other compliance regulations exist and are often specific to a particular industry.

Dealing with regulatory requirements is a hard task for many organizations. Troubles come from two directions. First, information technology personnel rarely have a legal background. Second, most requirements lack technical depth. This is because people drafting the regulations lack the information technology background. Many regulations are vague in their requirements. Therefore, proper technologies, depth of controls, and control frameworks become an important tool. Part 2 of this book provides an overview of different frameworks you can leverage.

Nevertheless, it is first important to understand why these requirements exist. In addition, you must have a broad understanding of which requirements exist.

Regulatory requirements exist at different levels. Those levels include state, federal, and international. In addition, industry consortiums propose requirements. It is important to know which regulations apply to your organization. This helps you ensure you stay compliant and prevents trying to solve the same problem twice. In most cases, you should consult corporate counsel or legal to help identify which regulations apply.

Warning

There is an irony in regulatory compliance laws. Although the laws might appear complicated, they make high-level points that are simple to understand. A problem occurs when people interpret regulations in different ways.

So what sources do people consult for IT compliance requirements? In 2005, the Burton Group asked attendees at one of its conferences this very question. The results were as follows:

Text of laws, 28 percent

Administrative code, 13 percent

External auditors, 23 percent

Internal auditors, 18 percent

Industry associations, 13 percent

Third-party guidelines, 5 percent

Warning

If you do business in other countries, you need to consider the requirements and compliance laws of those foreign countries. In addition, many U.S.-based companies rely on foreign, third-party service providers. This could result in noncompliance with U.S. regulations.

Regulatory compliance is nothing new. However, government oversight and strong compliance regulations greatly increased in the early 2000s. This was mainly due to corporate scandals—Enron, WorldCom, and others. Consider how quickly the Web and other information technologies advanced. Then, the increased focus on IT and IT security becomes more apparent. Yet regulatory requirements and industry standards are not without their critics. Critics accuse requirements regulating publicly traded companies of putting U.S. corporations at a disadvantage. At the same time, they discourage listing on the U.S. stock exchanges. Further, critics describe laws regulating federal information systems as bureaucratic without helping security. Furthermore, consider the payment card standards. Critics call these standards unfair for small businesses, and criticize the standards for failing to provide enough security.

The Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA) is contained within the E-Government Act of 2002, Public Law 107-347, as Title III. This act grants the importance of sound information security practices. It also controls the interest of national security and the economic well-being of the United States.

The purpose of FISMA is to do the following:

Provide a framework for effective information security resources that support federal operations, data, and infrastructure.

Accept the interconnectedness of IT. Ensure effective risk management is in place.

Ensure coordination of information security efforts between civilian, national security, and law enforcement communities.

Facilitate the development and ongoing monitoring of required minimum controls to protect federal information systems and data.

Provide for increased oversight of federal agency information security programs.

Recognize that information technology solutions may be acquired from commercial organizations. Leave the acquisition decisions to the individual agencies.

The need for FISMA started during the 1990s. Government agencies became more like commercial organizations. They started to transition from traditional mainframe computing to internetworked systems. As the Web became commonplace, federal agencies started to develop their own Web sites and offer online services. There was a sudden awareness that systems were more open and vulnerable than before. This eventually got the attention of Congress.

FISMA tasked the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to develop and set standards and guidelines. These apply only to federal information systems. Standards help categorize information and the systems. They are based on a risk-based approach. They include the minimum information security controls. For example, standards include the management, operational, and technical controls to apply to the information systems.

Warning

FISMA provides for what NIST cannot develop. NIST standards and guidelines apply to federal information systems. However, they do not apply to national security systems. According to FISMA, standards and guidelines for national security systems "shall be developed, prescribed, enforced, and overseen as otherwise authorized by law and as directed by the President."

In support of FISMA, NIST developed the following publications:

FIPS Publication 199, "Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems"

FIPS Publication 200, "Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems"

NIST Special Publication 800-18, "Guide for Developing Security Plans for Federal Information Systems"

NIST Special Publication 800-30, "Risk Management Guide for Information Technology Systems"

NIST Special Publication 800-37, "Guide for the Security Certification and Accreditation of Federal Information Systems"

NIST Special Publication 800-39, "Managing Risk from Information Systems: An Organizational Perspective"

NIST Special Publication 800-53, "Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems"

NIST Special Publication 800-53A, "Guide for Assessing the Security Controls in Federal Information Systems"

NIST Special Publication 800-59, "Guidelines for Identifying an Information System as a National Security System"

NIST Special Publication 800-60, "Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories"

To comply with FISMA, the appointed inspector general of the agency performs a separate, annual evaluation. The evaluation first tests the value of the IT security policies, procedures, and practices. A subset of the information systems within the particular agency is tested. If no inspector general exists, an independent external auditor performs it. The external auditor submits the results to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The OMB is a cabinet-level office within the Executive Office of the President of the United States with oversight responsibilities. The OMB compiles the data from each agency. The OMB then prepares an annual report to Congress on compliance with the act.

Tip

The annual reports submitted to Congress from the OMB concerning FISMA compliance are publicly available online. You can find them at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/legislative_reports.

At first, it appears only federal agencies need to worry about compliance, but this is not true. Federal agencies, for example, must care about their own systems as well as the systems of other contractors or organizations supporting the agencies. Any company or organization that expects to conduct business with the federal government needs to concern itself with FISMA.

The United States Department of Defense (DoD) is a federal department. It is responsible for all agencies of the government relating to national security and the military. The DoD imposes many requirements upon the management of their information systems for both DoD-related systems. The same goes for organizations that work with, contract, and provide services for the DoD. These requirements are within many federal laws and regulations. These laws span over a period of decades. Given the fast-paced change around information technology, requirements have been rapidly evolving. This is especially true as systems have moved from traditional mainframe computing to more distributed and interconnected computing.

Information resource management (IRM) is the process of managing information resources to improve performance and accomplish the mission of defense agencies. The Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980 introduced IRM into law. This act provides the OMB with oversight concerning IRM. This oversight assumes that within the OMB's policies, individual agencies can maintain their own IRM.

In later years, various amendments strengthened the original implementation of the law. Most notably, agencies needed to develop processes to acquire, control, and assess information systems. In spite of these laws, the 1990s saw a large rise of distributed networking technology. This only created more IT management issues for the DoD.

In 1996, Senator William Cohen led further reform. The reform streamlined the process of acquisition of IT resources. The position of chief information officer (CIO) was formed within federal departments and agencies. This CIO position was previously the senior IRM official. Now the title was more like the civilian role and reported directly to the agency head. This gave it a more strategic focus with greater accountability to solve the IT problems plaguing the agencies.

There are many laws and regulations to the DoD. These laws are both external and internal. They guide the operation, management, and protection of information systems. A summary of the key laws, regulations, and policies include the following:

Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995—Furthers the goal of the original act to have federal agencies take more responsibility and be held more publicly accountable in reducing the paperwork on the public

Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996—Formerly the Information Technology Management Reform Act, it improves the acquisition, use, and disposal of federal IT resources

House of Representatives Report 104-450 Conference Report—Contains provisions for acquisition and management issues related to IT

OMB Circular, A-130, Management of Federal Information Resources—Includes procedural guidelines for the management of federal information resources

OMB Circular A-11, Section 53, Information Technology and E-Government—Allows the agencies and OMB to review and assess IT spending across the federal government to provide for more effective operations, including ensuring privacy and compliance with other acts

Designation of the Chief Information Officer of the Department of Defense memorandum—Designates the role of CIO within the DoD

10 U.S.C. Section 2223, Information Technology: Additional Responsibilities of Chief Information Officers—Assigns additional responsibilities for CIOs

10 U.S.C. Section 2224, Defense Information Assurance Program—Provides for protection and defense of DoD information and information systems, and ensures availability, integrity, authentication, nonrepudiation, and rapid restoration of information and information systems

Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA)—Establishes a framework for effective information security in regard to information resources that support federal operations

E-Government Act of 2002—Improves the management of electronic government services by establishing a framework that requires using the Internet and related technologies to improve citizen access to government information services

DoD Directive 5144.01, Assistant Security of Defense for Networks and Information Integration/DoD Chief Information Officer—Assigns responsibilities, functions, relationships, and authorities to the DoD CIO

DoD Directive 8000.01, Management of the Department of Defense Information Enterprise—Provides guidance for creating an "information advantage" for the DoD and those that support its mission

As part of FISMA, all federal systems and applications must adhere to well-known security requirements. These requirements are documented and authorized. This process is known as Certification and Accreditation (C&A). It is essentially a process of auditing federal systems before putting them in a production environment. C&A recertifies every three years. The C&A process ensures that efforts are made to mitigate risks. Security controls on information systems must be properly implemented and maintained. It supports risk-management activities. At a high level, C&A allows the government to conduct consistent and repeatable assessments of security controls. They also gain awareness into risks and allow authorized officials to more confidently accredit or validate a system. The accreditation aspect is an accountable process. An official reviews the applied security controls. Then, the official approves or accepts risks to the system and organization.

Accreditation holds you accountable for the decision. Therefore, it is important to make the decision after reviewing documentation and supporting evidence. All must be complete, valid, and accurate. This is the certification part of C&A. Certification includes the technical controls as well as the management and operational controls.

Certification and Accreditation use three methodologies:

DoD Information Assurance Certification and Accreditation Process (DIACAP)

National Information Assurance Certification and Accreditation Process (NIACAP)

NIST Guide for the Security Certification and Accreditation of Federal Information Systems

Of the three, most agencies, including civilian organizations, embrace the NIST methodology.

All three methodologies are similar in their intent and require a thorough review of the systems. The information system owner submits a package of documents or accreditation package. The accrediting authority audits the package. A decision is made about accreditation for the information system. An accreditation package includes the following documents:

System security plan—The requirements, agreed security controls, and supporting documents. Examples are network diagrams, data flows, and risk assessment.

Security Assessment report—The evaluation results of security controls. This report might also include recommendations.

Plan of action and milestones—The details mitigating controls. You may plan or apply controls to reduce vulnerabilities. You can also plan or apply measures to correct any deficiencies.

Conducting the C&A process requires four phases. Assigned individuals carry out the various tasks in each phase. Figure 2-1 illustrates the following four phases:

Initiation—Before certification begins, initiation ensures all parties are in agreement with the plan. Initiation also ensures that appropriate documentation is completed.

Security certification—Security certification involves the process of actually assessing the security controls on the information system. It assesses controls to ensure they are implemented and operating as planned. A subsequent plan notes and addresses any deficiencies for remediation. When the assessment is done, the security certification documentation is created.

Security accreditation—With the security certification information, the system might receive accreditation. Remaining system vulnerabilities are considered. If the resulting risk is acceptable, accreditation results in one of three ways:

Authorization

Denial of authorization

Interim authorization

Continuous monitoring—Continuous monitoring provides ongoing assurance that the security controls stay in place. Configuration management and security monitoring alerts the authorizing authority if changes affect systems.

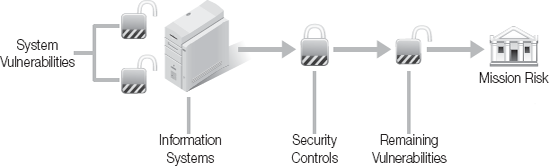

Security certification and accreditation pertain to a specific information system. They don't determine the risk level to the agency. To determine risk at the higher agency level, you must take a more holistic view. This must consider all information systems. Figure 2-2 shows how information system controls and vulnerabilities relate to the agency's mission risk.

Department of Defense Directive 8500.1 establishes policy and assigns responsibilities under Section 2224 of title 10 USC. They achieve DoD information assurance (IA) through defense in depth and integrating personnel, operations, and technology. IA includes all DoD-owned and DoD-controlled information systems that use DoD information. This is regardless of sensitivity. Information assurance is the controls that protect and defend information and information systems by ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and availability. It also provides authentication and nonrepudiation.

DoD needs to protect information and the systems that support that information. Information assurance grasps the natural vulnerabilities in systems that transmit, store, or process data. The vulnerability stems from the following:

Reliance upon commercial information technology solutions and services

Increased complexity through interconnectedness

Fast pace in which technology changes

Distributed and nonstandard management structure of a global network

Low cost of entry for attackers

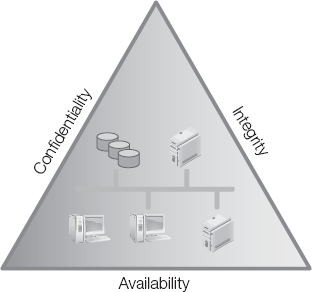

Protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability are common security objectives for information systems. This forms the foundation for information assurance.

Note

Confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) are often referred to as the security triad or the CIA triad.

Confidentiality—Ensuring that information is not disclosed to unauthorized sources. Loss of confidentiality occurs when data is open to some unauthorized entity or process.

Integrity—Ensuring the protection against unauthorized modification or destruction of data. Integrity also includes the quality of an information system regarding logical completeness and reliability of the hardware, software, and data structures.

Availability—Ensuring the timely and reliable access to data and services for authorized users.

Figure 2-3 shows these three security objectives as a protective triangle. If any side of the triangle fails, security fails. In other words, threats to the confidentiality, integrity, or availability represent risk.

In addition, the DoD considers authentication and nonrepudiation as two additional measures. These two are joined along with confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Authentication establishes the substance of a transmission, message, and originator. It also verifies an entity that has authorized access to information. Nonrepudiation provides assurance of proof of delivery and proof of identity. This way, neither party can later deny having processed or received the data.

You can easily describe implementing information assurance as a system for managing risk. It is built upon five principles defined within DoD Directive 8500.2, "Information Assurance (IA) Implementation," These five competencies are as follows:

The ability to assess security needs and capabilities

The ability to develop a purposeful security design or configuration that adheres to a common architecture and maximizes the use of common services

The ability to implement required controls for safeguards

The ability to test and verify

The ability to manage changes to an established baseline in a secure manner

In 1996, a U.S. federal law called the Information Technology Management Reform Act of 1996 was passed. The goal was to improve how the federal government acquires, uses, and disposes of information technology. The act is now called the Clinger-Cohen Act (CCA), named after its cosponsors. The CCA worked with other related legislation to spawn the DoD's Acquisition of IA strategy, DoD 5000.02 to ensure compliance. The Acquisition Information Assurance Strategy provides the groundwork for Certification and Accreditation. However, it is a separate process, which requires compliance. Information assurance compliance is required for any IT system, including those IT-based processes that are outsourced.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, also known as Sarbox or SOX, is a U.S. federal law. It is the result of the Public Company Account Reform and Investor Protection Act and Corporate Accountability and Responsibility Act. Sarbanes-Oxley dramatically changed how public companies do business.

The bill stems from the fraud and accounting debacles at companies such as Enron and WorldCom. Former President Bush characterized the act "as the most far reaching reforms of American business practices since the time of Franklin Delano Roosevelt." The act's primary purpose was to restore public confidence in the financial reporting of publicly traded companies. As a result, the act mandated many reforms to enhance corporate responsibility, enhance financial disclosures, and prevent fraud. Sarbanes-Oxley consists of the following 11 titles:

Title I, Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)—It establishes the PCAOB. The PCAOB has several responsibilities, including overseeing public accounting firms, defining the process for compliance audits, and enforcing SOX compliance.

Title II, Auditor Independence—It establishes the conditions of services an auditor can perform while remaining independent. For example, a public accounting firm that performs external auditing services cannot provide financial information systems design or internal audit outsourcing services.

Title III, Corporate Responsibility—It requires the formation of audit committees. It also establishes the interactions between the committee and external auditors. Perhaps one of the more notable mandates of SOX is contained in Section 302, which requires the chief executive officer (CEO) and the chief financial officer (CFO) to take individual responsibility in certifying and approving the integrity of the company's financial reports.

Title IV, Enhanced Financial Disclosures—It addresses the accuracy and features of financial disclosures. For example, this title specifically addresses and prevents what Enron did, such as selling liabilities on its balance sheet as assets to Special Purpose Entities (SPEs). This title also contains the controversial Section 404. Section 404 requires companies to report the adequacy of their internal controls.

Title V, Analyst Conflicts of Interest—It fosters public confidence in securities research. This title defines code of conducts between firms.

Title VI, Commission Resources and Authority—It provides greater authority to the SEC to fault or bar a securities professional from practice. This title also addresses the prevention of fraud schemes involving low-volume, low-price stocks.

Title VII, Studies and Reports—It requires the comptroller general and the SEC to conduct studies and report their findings. Examples include studying the effects of the consolidation of public accounting firms as well as studying previous corporate fraud and accounting scandals.

Title VIII, Corporate and Criminal Fraud Accountability—It provides the ramifications for corporate fraud and addresses the destruction of corporate audit records. This is a direct response to the auditing firm, Arthur Andersen, for shredding documents.

Title IX, White Collar Crime Penalty Enhancement—It reviews the rules and penalties regarding white-collar criminal offenses.

Title X, Corporate Tax Returns—It simply states that the CEO should sign the company tax return.

Title XI, Corporate Fraud Accountability—Also known as the Corporate Fraud Accountability Act of 2002, this title provides additional guidelines regarding consequences of corporate fraud. It also provides the SEC with the authority to freeze the funds of companies suspect in violating laws.

Sarbanes-Oxley is quite large and contains many reforms to rally public confidence. It also improves corporate accountability and helps to avoid corporate fraud and dishonesty. Two sections receive much of the attention, especially of IT. The first is Section 302, "Corporate responsibility for financial reports." The second is Section 404, "Management assessment of internal controls." These two sections place vast constraints on IT security. Although neither section mentions IT or IT security, financial accounting systems rely heavily on IT infrastructure. Thus, it has strongly driven the subject of IT security into the boardroom.

Section 302 requires the CEO and CFO to personally certify the truthfulness and accuracy of financial reports. They start and make internal controls. Then, they must assess and report upon the internal controls around financial reporting every quarter. Section 404 goes a step further. Section 404 requires the company to provide proof. Again, they must assess the effectiveness of their internal controls, to which a public accounting firm must audit and attest. They then publish this information in the company's annual report.

SOX is lengthy and is specific in many areas, for example, criminal penalties for noncompliance. It still is very high level and leaves a lot of room for interpretation, especially concerning IT controls. SOX does not directly address IT control requirements. As a result, you need to become familiar with a couple of publications. These include the auditing standards created by the PCAOB and the SEC's release on management guidance—17 CFR Part 241. In this codification, the SEC issued further interpretation and guidance regarding Section 404. It provides "an approach by which management can conduct a top-down, risk-based evaluation of internal control over financial reporting." PCAOB also made a formal process to further define the criteria within Section 404. This process became Auditing Standard No. 2. This standard supersedes Auditing Standard No. 5. Some notable changes to provide greater clarity and a more prescriptive approach include the following four areas:

Aligning Auditing Standard No. 5 with the SEC's management guidance, mostly in regard to prescriptive requirements and definitions

Adjusting the audit to account for the particular circumstances regarding the different size and complexities of companies

Encouraging auditors to use professional judgment, particularly in using a risk-assessment methodology

Following a principles-based approach to determining when and to what extent the auditor can use the work of others to obtain evidence about the design and effectiveness of the control

The standard also states that the auditor should use the "same suitable, recognized control framework" as the management of the company they are auditing. Furthermore, it even goes as far to suggest a suitable framework. That framework is the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) of the Treadway Commission. Chapter 4 explores frameworks such as COSO and others in greater depth.

Also known as the Financial Modernization Act of 1999, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) repeals parts of the Glass-Steagall Act from 1933. The Glass-Steagall Act prohibited banks from offering investment, commercial banking, and insurance services all under a single umbrella. GLBA deregulates the split of commercial and investment banking.

GLBA also provides provisions for compliance within Sections 501 and 521 to protect the financial information held by the industry. This protection is on behalf of the consumers. GLBA generally applies to financial institutions or any organization "significantly engaged" in financial activities. Examples include banks and securities firms. More examples are firms dealing with mortgages, insurance, tax preparation, debt collection, and much more. The FTC maintains and enforces GLBA.

To protect personally identifiable information (PII), GLBA divides privacy requirements into three principal parts. Those parts are the Financial Privacy Rule, Safeguards Rule, and Pretexting provisions:

The Financial Privacy Rule governs the collection and disclosure of customers' personal financial information.

The Safeguards Rule requires financial institutions to develop, maintain, and implement policies. These policies should tell how they will protect customer information.

The Pretexting provisions protect consumers. This protection is from both individuals and organizations that obtain personal financial information under false pretenses.

The Financial Privacy Rule requires financial institutions to provide notices to their customers. The notices explain their privacy policies, specifically covering the information collection and sharing practices of the company. The consumer is also given control over limiting the sharing of their information or opting out. If the financial institution changes its policy, they must provide another notice to the consumer.

The Safeguards Rule requires financial institutions to develop an information security policy to consider the nature and sensitivity of the information they handle. The plan must include and the company must comply with the following:

Designate at least one employee to coordinate an information security program.

Assess the risks to customer information within each pertinent area of the company's operation. Evaluate the effectiveness of the current safeguards and risk controls.

Implement a safeguard program. Regularly monitor and test it.

Choose service providers that can maintain appropriate safeguards, and govern their handling of customer information.

Evaluate and adjust the security program in view of events and changes in the firm's operations.

Likely, most organizations will protect against pretexting as part of their information security program. The best defense against pretexting is not technical, but rather awareness and training. Training is for both employees and customers. The Pretexting provision makes it illegal to do the following:

Make a false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation to obtain customer information from the financial institution or from their customers.

Use forged, counterfeit, lost, or stolen documents to obtain customer information from the financial institution or from their customers.

U.S. Congress enacted the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in 1996. The primary purpose of the statute is twofold. First, it provides for helping citizens maintain their health insurance coverage. Second, it improves efficiency and effectiveness of the American health care system. It does so by combating waste, fraud, and abuse in both health insurance and the delivery of heath care. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is responsible for publishing requirements and for enforcing HIPAA laws. However, the Office of Civil Rights, a subagency of HHS, administers and enforces the Privacy Rule and Security Rule of HIPAA. These laws are divided across five titles, which include the following:

Title I, Health Care Access, Portability, and Renewability

Title II, Preventing Health Care Fraud and Abuse, Administrative Simplification; Medical Liability Reform

Title III, Tax-Related Health Provisions

Title IV, Application and Enforcement of Group Health Plan Requirements

Title V, Revenue Offsets

Warning

Hippo has the letter "P" in it twice—not HIPAA. Surprisingly, many vendors that sell HIPAA solutions and even the government are guilty of misspelling the acronym for the legislation incorrectly in printed literature and on Web sites.

Much of the focus around HIPAA is within the first two titles. Title I offers protection of health insurance coverage without regard to pre-existing conditions to those, for example, who lose or change their jobs. Title II provides requirements for the privacy and security of health information. This is often referred to as Administrative Simplification. The broader law calls for the following:

Standardization of electronic data—patient, administrative, and financial—as well as the use of unique health identifiers

Security standards and controls to protect the confidentiality and integrity of individually identifiable health information

As a result, the HHS has provided five rules regarding Title II of HIPAA. These include the Privacy Rule, the Transactions and Code Sets Rule, the Security Rule, the Unique Identifiers Rule, and the Enforcement Rule. These five rules impact and affect information technology operations within organizations. Specifically, the Privacy Rule and Security Rule affect information security. HIPAA is primarily concerned with protected health information (PHI). PHI means individually identifiable health information. PHI relates to physical or mental health of an individual. It can also relate to the delivery of health care to an individual as well as payment for the delivery of health care.

The Privacy Rule went into effect in 2003. It regulates the use and disclosure of PHI by covered entities. A covered entity, for example, includes health care providers, health plans, and health care clearinghouses. In many ways, the Privacy Rule drives the Security Rule. Under the law, covered entities are obligated to do the following:

Provide information to patients about their privacy rights and how the information can be used.

Adopt clear privacy procedures.

Train employees on privacy procedures.

Designate someone to be responsible for overseeing that privacy procedures are adopted and followed.

The Security Rule followed the Privacy Rule. Unlike the Privacy Rule, however, the Security Rule applies just to electronic PHI (ePHI). The Security Rule provides for the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of ePHI, and contains three broad safeguards. These safeguards include the following:

Administrative safeguards

Technical safeguards

Physical safeguards

Each of the preceding safeguards consists of various standards. All are required or addressable. Required rules must be implemented, but addressable standards provide flexibility. This way, an organization can decide how to reasonably and appropriately meet the standard. Bear in mind, however, that addressable does not mean optional.

Administrative safeguards primarily consist of policies and procedures. They govern the security measures used to protect ePHI. Table 2-1 provides a summary of the administrative safeguards, including the required and addressable standards.

Table 2-1. HIPAA administrative safeguards and implementation specifications.

SAFEGUARD | IMPLEMENTATION SPECIFICATION | REQUIRED/ADDRESSABLE |

|---|---|---|

Security management process | Risk analysis Risk management Sanction policy Information system activity review | Required Required Required Required |

Assigned security responsibility | Not applicable | Required |

Workforce security | Authorization and/or supervision Workforce clearance procedure Termination procedures | Addressable Addressable Addressable |

Information access management | Isolating health care clearinghouse function Access authorization Access establishment and modification | Required Addressable Addressable |

Security awareness and training | Security reminders Protection from malicious software Logon monitoring Password management | Addressable Addressable Addressable Addressable |

Security incident procedures | Response and reporting | Required |

Contingency plan | Data backup plan Disaster recover plan Emergency mode operation plan Testing and revision procedures Applications and data criticality analysis | Required Required Required Addressable Addressable |

Evaluation | Not applicable | Required |

Business associate contracts and other arrangements | Written contract or other arrangement | Required |

Physical safeguards include the policies, procedures, and physical controls put in place. These controls and documentation protect the information systems and physical structures from unauthorized access. The same goes for natural disasters and other environmental hazards. The physical safeguards include the four standards shown in Table 2-2, along with the implementation specifications.

Technical safeguards consist of the policies, procedures, and controls put in place. These safeguards protect ePHI and prevent unauthorized access. Table 2-3 lists the five safeguards and corresponding implementation specifications.

Although covered entities must comply with the previously listed safeguards and implementation specifications, there isn't a safeguard listed that should surprise organizations. In fact, most of these safeguards are addressed through best practices for any sensitive information.

In 2006, the Final Rule for HIPAA was issued—the Enforcement Rule—and set the penalties to be levied as a result of HIPAA violations. The Enforcement Rule also established the procedures for investigations and hearings into noncompliance. The potential for increased enforcement of noncompliance to HIPAA was later introduced in 2009 when the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act was signed into law. HITECH was signed in as part of the American Recover and Reinvestment Act (ARPA). In addition to laying the groundwork for increased enforcement, HITECH also adds requirements for a breach notification. The notification is what an organization puts in action should PHI becomes disclosed in a readable, that is, nonencrypted, format.

Table 2-2. HIPAA physical safeguards and implementation specifications.

SAFEGUARD | IMPLEMENTATION SPECIFICATION | REQUIRED/ADDRESSABLE |

|---|---|---|

Facility access controls | Contingency operations Facility security plan Access control and validation procedures Maintenance records | Addressable Addressable Addressable Addressable |

Workstation use | Not applicable | Required |

Workstation security | Not applicable | Required |

Device and media controls | Disposal Media reuse Accountability Data backup and storage | Required Required Addressable Addressable |

Table 2-3. HIPAA technical safeguards and implementation specifications.

SAFEGUARD | IMPLEMENTATION SPECIFICATION | REQUIRED/ADDRESSABLE |

|---|---|---|

Access control | Contingency operations Facility security plan Access control and validation procedures Maintenance records | Required Required Addressable Addressable |

Audit controls | Not applicable | Required |

Integrity | Mechanisms to authenticate ePHI | Addressable |

Person or entity authentication | Not applicable | Required |

Transmission security | Integrity controls Encryption | Addressable Addressable |

The Children's Internet Protection Act (CIPA) is a federal law introduced as part of a spending bill that passed Congress in 2000. The FCC maintains and enforces CIPA. This act addresses concerns about children's access to explicit content online, such as pornography at schools and libraries, by requiring the use of Internet filters as a condition of receiving federal funds. CIPA is a result of previous failed attempts at restricting indecent content. The Communications Decency Act and the Child Online Protection Act faced Supreme Court challenges over the United States First Amendment. The reason was the act violated the right of free speech contained within the Constitution.

CIPA does not provide for any additional funds for the purchase of mechanisms to protect children from explicit content. Instead, conditions are attached to grants and to the use of E-Rate discounts. "E-Rate" is a program that makes Internet access more affordable for schools and libraries.

CIPA requires schools and libraries to certify compliance to implement an Internet safety policy and implement "technology protection measures." This means having technology in place that blocks or filters Internet access that is either obscene, harmful to minors, or represents child pornography. This includes implementing a safety policy and controls that address the following:

The safety and security of minors when using electronic communication such as e-mail, chat rooms, and instant messaging

Unauthorized access and unlawful activities by minors

Unauthorized disclosure, use, and dissemination of personal information regarding minors

Measures restricting minors' access to harmful materials

Prior to implementing the policy and controls, however, the law also requires schools or libraries to first provide public notice and to hold a public hearing to address the proposed Internet safety policy.

You might have noticed that the term "inappropriate matter" could be considered vague and controversial. As a result, the act is clear in stating that the government may not establish the criteria for making such a determination. The act states that the determination is made at the local level by the school board, local educational agency, or library.

Finally, schools and libraries must comply with one more step before they can receive the E-Rate. They must certify they have an Internet safety policy in place meeting the preceding requirements. Noncompliance with the law occurs if there is a failure to submit for certification. In this case, the institution will not be eligible for services at the discounted rate. In addition, failure to ensure the use of the computers in accordance with a certification will be required to reimburse all funds and discounts for the certification period.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) of 1974 is a U.S. federal law. FERPA protects the privacy of student education records. It also provides parents certain access rights to the student's educational records. Parental access rights stop once the student enters post-secondary education or the student turns 18 years old. The regulation applies to educational institutions that receive federal funding from the U.S. Department of Education.

Educational agencies or institutions should notify parents or eligible students of their rights under the law annually. The notice includes the right to do the following:

Review the student's educational records. Under most situations, the school is not required to provide copies. They may charge to provide copies.

Seek correction or revision of the educational records if believed to be inaccurate or a violation of privacy. If the school doesn't make any amendments, a formal hearing may be requested. If the school still doesn't make any changes, the parent or eligible student may place a statement regarding the content in question.

Consent to disclosure of educational records. Schools, however, may disclose "directory information." However, schools must give parents or eligible students opportunity to restrict disclosure of the information. Disclosure of educational records and nondirectory information without consent is provided under certain conditions of the law.

File a complaint with the department in regard to failures to comply with the act.

As the name implies, directory information is personal data that you can find in publicly available sources. For example, a publicly available source could be a phone book or yearbook. Such information is not considered a harmful invasion of privacy. Examples of directory information include the following:

Name

Address

Telephone number

Date and place of birth

Honors and awards

Date of attendance

Warning

You may never disclose Social Security numbers as directory information, under the FERPA regulations. You cannot even use the last four numbers of your Social Security number, which is common across other industries.

Nondirectory information, on the other hand, includes, for example, Social Security numbers and transcripts.

In 2008, two relevant documents were published. The first was "Joint Guidance on the Application of the Family Educational Rights." The second was the "Privacy Act (FERPA) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) to Student Health Records." Many schools and universities operate health clinics. Thus, it is important that educational and health records kept at health facilities on campus are only subject to FERPA and not HIPAA. If the institution is a post-secondary school that provides health care to nonstudents, the health information of the nonstudent patients is subject to HIPAA.

Compliance with the law is typically the responsibility of the registrar's office, which in turn works with legal counsel. However, IT professionals should be involved in the process and understand FERPA to ensure compliance. The act was originally drafted in 1974, so distributed, networked computer technology was not around yet. Therefore, interpretation of the law is sometimes needed. Recent changes do help accommodate this technical evolution. Consider that the real meaning of FERPA is access and confidentiality. Access in that parents or eligible students must be permitted access to their records. Confidentiality in that education records must be protected and not released without written consent. Then, consider the number of electronic records relating to students that are likely to be stored on file servers and within databases. It is more difficult because IT makes tasks so easy, such as submitting and retrieving grades electronically, Web-based financial aid, and course registration.

Under the FERPA Final Rules issued in 2008, FERPA does address further requirements and guidelines around information systems.

Note

In the past, FERPA did not allow student ID numbers to be disclosed as directory information because they are used to both identify and authenticate the student. If a student identifier is not used to access records or used for authentication, such as a password, it may be treated as directory information.

The changes also recommend "educational agencies and institutions to utilize appropriate methods to protect education records, especially in electronic data systems." The update also addresses several examples of data breaches and the unauthorized disclosure of information. It also expresses concerns that data may be compromised as a result of failure to implement proper security controls. Yet the update does not dictate how to properly safeguard electronic records, but instead offers additional resources, for example, NIST, on how to protect the information.

FERPA now provides suggestions on what to do in the case of an inadvertent release of data on the Internet or other unauthorized disclosure. In case of unauthorized disclosure, FERPA doesn't require notification. That is, the school does not have to issue direct notices to the parents or students. However, it does require the school to maintain a record of the disclosure. FERPA advises that direct notification should occur if the unauthorized disclosure might lead to identity theft. Nevertheless, other laws might still require institutions to provide direct notification.

Chapter 1 introduced you to TJX, a company that suffered a serious breach in which it had millions of credit card numbers stolen. TJX was not the first, however, nor are they the last. Individual credit card companies started formulating programs to prevent breaches from occurring. These programs ensured that merchants meet baseline security requirements for how they store, process, and transmit payment card data.

The five leading credit card companies—Visa, MasterCard, American Express, JCB, and Discover—came together and formed the Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council (PCI SSC) in 2004. To help organizations that process card payments prevent credit card fraud, PCI SSC created the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). PCI DSS is a set of requirements that prescribe operational and technical controls to protect cardholder data.

Adhering to PCI DSS requires three ongoing steps:

Assess—Identify cardholder data as well as all related IT infrastructure and processes. This involves making sure adequate controls are in place and testing for vulnerabilities.

Remediate—Eliminate the storage of unnecessary data and fix discovered vulnerabilities.

Report—Submit validation records and compliance reports.

PCI SSC manages the overall program. However, card vendors have their own programs for compliance and enforcement. Determination of requirements depends upon the volume of card transactions that take place. Any organization, however, that holds, processes, or passes cardholder data must undergo annual assessment. The assessment is required regardless of amount. In general, organizations that process a smaller number of transactions might only need to complete a Self-Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ). Organizations with high-volume transactions must meet other requirements, such as assessment by an independent firm. The firm must be designated as a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA). In addition, requirement 11.2 requires vulnerability scans. The scans are done quarterly and are performed by a PCI Approved Scanning Vendor (ASV).

Tip

There are many acronyms, but PCI DSS, SAQ, QSA, and ASV are some good acronyms to become familiar with. A list of qualified QSAs and ASVs is located at the PCI SSC Web site at http://www.pcisecuritystandards.org. The Web site also has procedures on how to become one.

PCI DSS is unlike most regulatory laws in one way. It is very specific in regard to requirements and expectations. The requirements generally follow security best practices and use the 12 high-level requirements, aligned across six goals, as shown in Table 2-4. Each requirement listed in the table consists of various subrequirements. Also included are procedures for testing. These must be documented as either being in-place or not in-place.

Consider requirement 8, for example. It requires a unique ID to be assigned to each person with computer access. Within the security standard, this requirement actually consists of 21 subrequirements. Many of them are very specific, for example:

Incorporate two-factor authentication for remote access.

Set first-time passwords to a unique value and change immediately after first use.

Remove or disable inactive accounts at least every 90 days.

Require a minimum password length of at least seven characters.

Since PCI DSS started, the Security Council has released several supplemental documents, including the following:

Information Supplement: Requirement 11.3 Penetration Testing—This provides clarification around penetration testing. It also discusses the difference from the PCI DSS-required vulnerability assessments.

Information Supplement: Requirement 6.6 Code Reviews and Application Firewalls Clarified—This recognizes the complexity and the possible unfeasibility of the original requirement. It provides further guidance regarding the intent and alternatives.

Navigating the PCI SSC—Understanding the Intent of the Requirements—This provides further discussion regarding the purpose of each of the requirements.

Information Supplement: PCI DSS Wireless Guidelines—This document provides further guidance and suggestions for deploying 802.11 wireless local area networks (WLANs).

Table 2-4. Goals and high-level requirements for PCI DSS.

GOALS | HIGH-LEVEL REQUIREMENTS |

|---|---|

Build and maintain a secure network. |

|

Protect cardholder data. |

|

Maintain a vulnerability management program. |

|

Implement strong access control measures. |

|

Regularly monitor and test networks. |

|

Maintain an information security policy. |

|

Based upon the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act of 2003, the Red Flags Rule was created to establish procedure for the identification of possible instances of identity theft. The FTC along with the credit union and banking regulatory agencies created the Red Flags Rule. They are also responsible for enforcing it. The Red Flags Rule requires all financial institutions and creditors to implement an Identity Theft Prevention Program. The goal is to detect warning signs or "red flags" of identity theft.

Note

The FTC works for the consumer to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, and unfair business practices in the marketplace. In addition, they provide information to help consumers identify, prevent, and stop such activity.

The law applies to financial institutions, such as banks, savings and loan associations, or credit unions. The law applies to any entity where a consumer has an account that conducts payments or transfers, such as a checking account. In addition, the law also applies to creditors. Creditors extend, renew, or continue credit. Examples include finance companies, mortgage brokers, utility companies, and automobile dealers. In both cases, the law only applies to financial institutions and creditors with covered accounts. Creditors use a covered account when there is a foreseeable risk of identity theft. A common example is an account used for household purposes. This includes such things as credit card accounts, mortgage loans, broker margin accounts, checking accounts, and so on.

To comply with the Red Flags Rule, financial institutions and creditors must follow the four basic elements. These involve having appropriate policies and procedures in place to do the following:

Identify red flags for covered accounts.

Detect red flags.

Respond to those red flags.

Update the program periodically.

Financial institutions are first responsible for identifying red flags for covered accounts. The regulation does not demand specific red flags. Instead, it requires the financial institution or creditor to identify and create a list of red flags on its own. The regulation offers guidelines, however, in identifying red flags. Table 2-5 lists the five categories provided by the regulation and includes an example of each.

After creating the list of relevant red flags from the preceding categories, the institutions must then put programs and procedures in place to be able to detect the red flags. The regulation provides very little guidance on how to do this, other than saying what most institutions are already doing. For example, guidance might include getting unique information, verifying the person opening the account gives accurate and real information, and ensuring transactions are monitored. For many organizations, effective detection relies upon technology solutions that specifically focus on solutions around authentication and fraud monitoring.

Table 2-5. Red Flag categories and an example of each.

CATEGORY | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|

Alerts, notifications, or other warnings received from consumer reporting agencies or service providers, such as fraud detection services | A recent and significant increase in inquiry volume |

The presentation of suspicious documents | A photograph or physical description on an identification not consistent with the applicant or consumer presenting the identification |

The presentation of suspicious personal identifying information, such as a suspicious address change | A Social Security number (SSN) that has not been issued or is listed as the number of a deceased individual |

The unusual use of, or other suspicious activity related to a covered account | A notification to the financial institution or creditor that the customer isn't receiving paper account statements |

Notice from customers, victims of identity theft, law enforcement, authorities, or other persons regarding possible identity theft in connection with covered accounts held by the financial institution or creditor | A notification from the customer to the financial institution or creditor of unusual activity |

Next, the financial institutions and creditors must respond to the red flags. This prevents and lessens identification theft. Organizations must respond accordingly. For example, this ranges from contacting the customer to notifying law enforcement.

Finally, financial institutions and creditors should know that risks to customers and themselves are constantly changing. On one hand, business changes can affect its risk tolerance. Examples include mergers and acquisitions as well as changes in the type of accounts offered to customers. On the other hand, methods of identity theft and how it's detected and prevented are constantly changing. A game of cat and mouse is the best way to describe the relationship among fraudsters, law enforcement, and vendors that provide prevention and detection tools.

In addition to private industry standards, such as PCI DSS, companies must be concerned with and comply with many laws. Such requirements might affect only specific industries, whereas others can span across industries. PCI DSS, for example, generally affects any organization that holds, processes, or passes payment cardholder information, regardless of industry. HIPAA, on the other hand, primarily affects the health care industry, and Sarbanes-Oxley pertains to any publicly traded company.

Although compliance to regulations can touch many different groups within an organization, IT departments are increasingly discovering they need to stay abreast of the latest regulations as IT has become pervasive throughout organizations. It might seem overwhelming to keep up with the requirements of all the regulations, not to mention new ones. However, a sound governance, risk-management, and compliance program within organizations using a well-defined framework can make the process much more efficient and effective.

Act of Congress

Approved Scanning Vendor (ASV)

Availability

Certification and Accreditation (C&A)

Children's Internet Protection Act (CIPA)

Confidentiality

Cyber, Identity, and Information Assurance (CIIA)

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA)

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA)

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

Information assurance (IA)

Information resource management (IRM)

Integrity

Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council (PCI SSC)

Pretexting

Protected health information (PHI)

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)

Qualified Security Assessor

Red Flags Rule

Regulatory agencies

Which of the following acknowledges the importance of sound information security practices and controls in the interest of national security?

FISMA

GLBA

HIPAA

FACTA

FERPA

What organization was tasked to develop standards to apply to federal information systems using a risk-based approach?

Public Entity Risk Institute

International Organization for Standardization

National Institute of Standards and Technology

International Standards Organization

American National Standards Institute

Certification and __________ is an audit of federal systems prior to being placed into a production environment.

Which of the following organizations was tasked to develop and prescribe standards and guidelines that apply to federal information systems?

NIST

FISMA

Congress

PCI SSC

U.S. Department of the Navy

What section of Sarbanes-Oxley requires management and the external auditor to report on the accuracy of internal controls over financial reporting?

Section 301

Section 404

Section 802

Section 1107

Sarbanes-Oxley explicitly addresses the IT security controls required to ensure accurate financial reporting.

True

False

Which of the following was established to have oversight of public accounting firms and is responsible for defining the process of SOX compliance audits?

COSO

Enron

PCAOB

Sarbanes-Oxley

None of the above

Which of the following is not one of the titles within Sarbanes-Oxley?

Corporate Responsibility

Enhanced Financial Disclosures

Analyst Conflicts of Interest

Studies and Reports

Auditor Conflicts of Interest

Which one of the following is not considered a principal part of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act?

Financial Privacy Rule

Pretexting provisions

Safeguards Rule

Information Security Rule

Which regulatory department is responsible for the enforcement of HIPAA laws?

HHS

FDA

U.S Department of Agriculture

U.S. EPA

FTC

Which one of the following is not one of the safeguards provided within the HIPAA Security Rule?

Administrative

Operational

Technical

Physical

In accordance with the Children's Internet Protection Act, who determines what is considered inappropriate material?

FCC

U.S. Department of Education

The local communities

U.S. Department of the Interior Library

State governments

While the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act prohibits the use of Social Security numbers as directory information, the act does permit the use of the last four digits of a SSN.

True

False

PCI DSS is a legislative act enacted by Congress to ensure that merchants meet baseline security requirements for how they store, process, and transmit payment card data.

True

False

To comply with Red Flags Rule, financial institutions and creditors must do which of the following?

Identify red flags for covered accounts.

Detect red flags.

Respond to detected red flags.

Update the program periodically.

Answers B and C only

All of the above