7

Focus groups

7.1 Introduction

Still at the ‘consult’ point of the spectrum, focus groups are a versatile and effective means of gaining insight into people’s opinions, feelings, preferences and experiences. The group dynamic is key; it gives participants the opportunity to see matters in new ways, hear different perspectives and discuss challenging questions. The aim is to encourage group responses more than individual viewpoints, and the facilitator’s role is vital in maximising participants’ involvement to yield good material. This chapter looks at setting aims and structure for focus group sessions, some practical and interpersonal issues to consider, running a group, and collecting, managing and analysing material.

Focus Groups

Methodology type:

qualitative

Level of participation:

consult

Time/resource needed for data collection:

medium

Time/resource needed for data analysis:

high

Useful for:

understanding site context

understanding attitudes/perceptions/values/feelings

testing/getting opinions/feedback

understanding behaviour/interactions/use of space

site planning/generating ideas

design development

7.2 Focus Group Research

Focus groups differ from the other group activities covered in these pages, in that the design team selects the participants. Whether to provide variety, balance or homogeneity, participants are chosen for a reason. (A group discussion open to anyone isn’t a focus group.) Focus groups are relatively inexpensive and simple to run, and the format suits a wide range of types of participants and topics. At the start of a project, less structured focus groups allow participants to set the agenda and discuss the issues that matter to them, which provides information that designers can use straight away. Further on in the design process, a more structured format can gather feedback on the work in progress and responses to design options.

For participants, focus groups are an opportunity to express themselves on their own terms and in their own words. Questions are mainly open-ended, and the relatively natural, conversational format means that sessions can (and should) be enjoyable for participants. Of course, not everyone feels comfortable talking to a group of strangers and there will always be participants who are less forthcoming; feeling they lack the knowledge or vocabulary to contribute, or nervous about disagreeing with majority views or dominant group members, for example. However, these dynamics can be managed by an experienced facilitator.

There’s no doubt that the facilitator’s ability is a significant factor in the success of a focus group. Getting maximum yield from the session requires considerable skill. Good listening and observation skills are vital, including for example, the ability to concentrate on what’s being said and not being said, picking up on verbal and non-verbal cues, probing, asking for details and explanations, and observing participants’ reactions during discussions.

Interpersonal skills are equally important to put everyone at ease and manage any tensions. Furthermore, the facilitator also needs a good understanding of the issues under consideration, as well as to be able to pick up on potentially significant matters that weren’t included in the prepared topic schedule. Recalling the impartiality ethic (see section 2.2) the facilitator must maintain a neutral position in discussions, and keep their feelings and opinions to themselves. On this basis, my advice is to use independent facilitators, rather than have staff running focus groups on projects in which they are involved.

7.3 Preparation

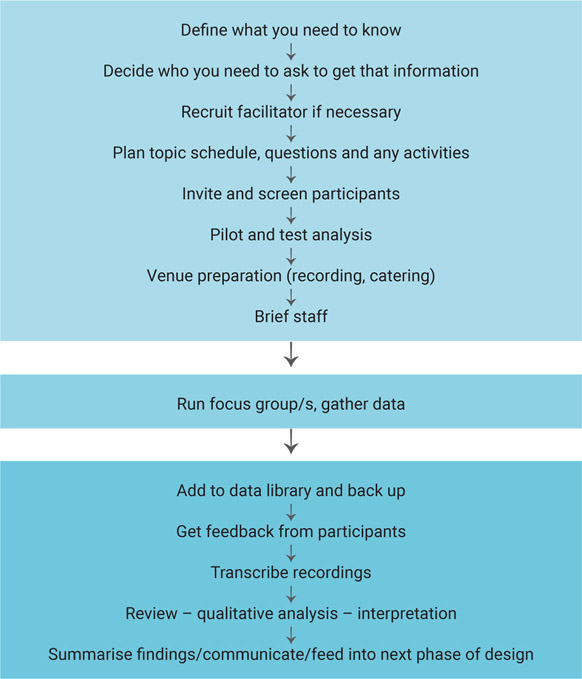

Figure 7.1

Suggested focus group process

Aims and structure

Before working out the who, where, when and how of setting up a focus group, start with the why. Its purpose must be clear. What is it meant to achieve? What are the questions that need answers? Figure 7.1 suggests a process for preparing and running a focus group. Whether using a structured format or not, prepare a list of topics to guide the session. Less is more; covering a few key topics in depth will yield better information than squeezing lots of issues into the time available. Having said that, the group make-up can play a part here. Homogenous groups can get through a list of topics quicker, as there tends to be greater consensus, whereas more mixed groups usually have a wider range of views and more potential for debate. So take these factors into account in working out what to cover in the session.

If several focus groups are planned, consider the level of question standardisation between them. Asking the same questions in each session means the material can be aggregated, but it can reduce the scope to pursue other interesting topics. Another option is a rolling question schedule. Participants discuss a set of topics in the first session, then issues arising from that session are brought to the second session, then the third session includes new topics that arose in the second, and so on. Although it allows less comparison between sessions, the groups will be able to cover more issues and generate more material (this may not necessarily be seen as an advantage at the analysis stage however!).

Using the funnelling technique described at section 6.4, start a session with general and easily answered questions and get everyone to contribute; then address more challenging topics. It’s sensible to cover the most important issues relatively early on while participants are still fresh and there’s plenty of time. When presenting information about the proposal, remember that participants may be unused to discussing planning and design issues in depth, so explain any terminology that might be unfamiliar, use everyday concepts and vocabulary, and keep checking for understanding. Discussing controversial or emotionally charged topics can be strenuous for participants, so this should also be factored into the schedule and followed by a break or a more enjoyable activity. Allow about 90 minutes maximum for the session overall.

Aim to gather information about participants’ experiences, opinions, feelings and preferences, with a good amount of content in each category. This means asking lots of open-ended questions, starting with, ‘What’s your experience of …’, ‘What do you think about …’ or ‘How would you feel if …’, for example. Ensure that questions are relevant to the group, that everyone will understand and will be able to answer them, and remember to ask follow-up questions for more details or explanations: ‘Why do you say that?’, ‘Could you say a bit more about what happened?’ And a question that’s always worth asking: ‘Does anyone have a different view?’

Selecting participants

Having drafted a workable session strategy and time plan, the next step is to put together a good group of people to answer the questions. Send a short screening survey to prospective participants first, explaining the objectives and gathering some details to help select the people who can most usefully contribute. Also include information about recording the session, confidentiality, details of the time and venue, accessibility, length of the session and what will be covered, and check they’re happy with these arrangements.

Normally the optimum group size is eight to twelve, although homogenous groups can work with slightly fewer or more than this. The group composition depends on the research objectives. Demographically similar groups will be needed for some issues, but a general mix is suitable when a broad range of perspectives is wanted. Demographic factors play a part in group dynamics, which in turn affects the responses offered. For instance, it’s been shown that men tend to dominate discussions in mixed-gender focus groups (Stewart and Shamdasani, 2014), something for the facilitator to monitor.

Venue

Choose a venue that’s fully accessible, that everyone can easily reach and where everyone will feel comfortable. Quiet and privacy are essential, so there are no interruptions or distracting background noise. Focus groups are more focused in rooms with natural light. Room size and layout also affect interactions, as people are more relaxed and forthcoming when they have a good amount of personal space, whereas smaller spaces tend to produce more intense debate and polarised opinions (Sanoff, 2000). Discussions flow better when everyone can see each other, so a round table is ideal. The facilitator’s position also influences dynamics; if they’re positioned outside the group, participants are more likely to talk to each other.

The day will run more smoothly with one or two colleagues helping out: greeting people as they arrive, taking care of refreshments, setting up recording equipment and making notes. They will also be able to help review and analyse material afterwards. Recording the session is essential, whether audio or video, and the equipment must be tested before the session to ensure it will pick up everyone’s voices clearly; a digital voice or audio recorder, or a video microphone with an omnidirectional setting works best with groups. Try and position recording equipment unobtrusively so participants are not conscious of it. Make sure batteries are fully charged and spares are on hand, that enough memory is available and that there’s a back-up option just in case.

If it’s possible to provide refreshments, then do so; participants will feel appreciated and more relaxed, and it helps create a more congenial atmosphere for discussion. For longer sessions it’s almost always necessary, and can provide a welcome break. But don’t have refreshments on the table during the session; eating and drinking sounds can easily obliterate the discussion!

Figure 7.2a

Figure 7.2b

Figure 7.2c

7.4 Running Focus Groups

Everything about the session should be designed to put participants at ease, from the venue and room layout to a friendly welcome on the door and decent refreshments. This isn’t just a matter of courtesy; relaxed participants yield good material. If people feel uncomfortable, they can become less forthcoming or more oppositional.

After introductions, the facilitator should briefly outline the event’s purpose and time schedule, then check that everyone agrees to being recorded, ask if there are any questions, and set out confidentiality requirements and ground rules. Emphasise that the group is about sharing ideas, listening, debating and working constructively together: that everyone’s contributions are equally valued, that there are no right or wrong answers, and that everyone should be treated courteously. Clarify that the facilitator’s role is to guide the discussion and to listen, not to chair a meeting or lead the group. Keep preliminaries as brief as possible though; people have come to talk and will be keen to get started.

Bias Issues in Focus Groups

Planning

Exclusion bias | Selection bias

Focus group participants are purposely chosen rather than self-selecting. Consider whose voices will be heard and not heard, and what effect this will have.

Data Collection

Interviewer bias | Procedural bias | Question-order bias

Consider whether the facilitator may have influenced the data by showing positive or negative responses to views expressed, or spending more time discussing favourable rather than unfavourable responses. Are there any practical or logistical factors that could impact on the data, such as time, venue, location or accessibility and assistance issues, which affect who can participate? What effect will the structure of the event have on the data, in terms of question order, covering topics, time allocation, etc?

Analysis

Confirmation bias | Culture bias | Focusing effect | Group attribution error | Observer-expectancy effect | Stereotyping

Does analysis of the qualitative data offer new insights or only find what was expected? Has all data been methodically analysed and considered or have specific aspects become the main focus? Are participants viewed as individuals expressing their personal opinions or as representatives of particular demographic groups?

Participants

Acquiescence bias | Anchoring | Base rate fallacy | Bikeshedding | Concept test bias | Consistency bias | Dominant respondent bias | First speaker bias | Habituation bias | Halo effect | Hostility bias | Ingroup bias | Moderator acceptance bias | Overstatement bias | Reactive devaluation | Shared information bias | Sponsorship bias

A multitude of factors shape the group dynamic, participants’ responses to the substance of the discussion, and their level of engagement with the process – all of which can create bias. A skilled facilitator can identify when these factors come into play and manage them to some extent, but it’s essential to consider their effects in analysis.

See the Appendix for explanations of these types of bias.

Gathering data

The facilitator might start with an icebreaker exercise, depending on the group’s make-up and purpose, or move straight on to the main business. As with the funnelling technique in questionnaires, start with factual and easily answered questions before discussing more complex issues.

Once the session is under way, the facilitator has two main tasks:

- Keeping to time. This means balancing participants wanting to pursue issues of interest with the need to cover the topic schedule within the time available. A good knowledge of the matter under discussion will enable the facilitator to judge the potential value of conversational tangents.

- Ensuring that all participants contribute. Any focus group will include talkative and reticent participants. The facilitator has to involve the reticent members, particularly in mixed groups, and manage the talkative ones. They might ask individuals to hold back so others can have their say, and the group may also self-regulate the discussion. To reduce the influence of more vociferous members and ‘first speaker effect’ (see the Appendix on types of bias) the facilitator can ask everyone to write down their responses to a question, then pool the answers for all to read.

One more thing that requires a facilitator’s constant vigilance throughout a session is their own neutrality. The facilitator should mask their personal reactions to participants’ views, guarding against verbal and non-verbal responses that imply approval or disapproval. As well as keeping comments and body language neutral, they need to give participants equal encouragement and time to speak, whether their comments are favourable or unfavourable, and avoid placing more emphasis on positive comments when summing up. This can be particularly challenging when designers run focus groups to get feedback on their work. But all participants’ responses must be treated equally, and the facilitator should seek to build rapport, listening attentively to everyone and expressing interest through tone of voice and body language. If participants look to the facilitator for validation of their views, as often happens, they can deflect the question back to the group and ask what other people think. This is another argument in favour of the facilitator sitting a little outside the group, reducing the temptation for participants to look for their reactions. Another key aspect of neutrality is avoiding leading questions, which either imply a preferred answer or guide participants away from certain responses. Desired outcomes shouldn’t shape how questions are worded.

The facilitator will need to take written notes during the session, without trying to capture every detail or being over-selective. It makes sense to record things beyond the substance of what was said: people’s expressions, non-verbal responses, group dynamics, comments that caused a notable reaction, and so on. The facilitator can usefully spend a few minutes after participants have left reviewing their notes to check for clarity, adding in detail and explanation as required, highlighting any significant themes or connections, and noting anything unexpected that may need to be looked at further. They should hold off at this stage from forming interpretations, and focus on asking questions about the data rather than trying to find answers.

Activities and exercises

Activities and exercises in focus groups are completely optional. For some groups or topics, discussion alone will yield enough good material; other groups may be more responsive to interactive elements. As always, start with the desired end results, look at what information is required and then work backwards to find the best ways to obtain it. Given the time constraints, any activities should be quickly explainable, short, fun and/or interesting, and easy for participants to complete. (Lengthier and more complex tasks, or idea-generating exercises suit workshops better.) Activities that work in focus groups call for immediate personal responses without needing any prior knowledge, such as:

- Prioritising/sorting exercises using cards, post-it notes, etc.

- Map- or model-based activities. Ask participants to identify things like places that they like and dislike, or routes they prefer and those they avoid.

- Image- or object-based activities. Pictures or artefacts are a good way to generate discussion, and are also effective in working with more sensitive topics. ‘Mood boards’ and collage can help people consider design options and identify preferences.

A useful insight from UX focus group research is that if participants are shown images of a product concept, they can form an opinion, but if they’re given a prototype to examine, they can give much more valuable feedback based on their first-hand experience. There’s certainly scope to use focus groups to consider usability issues more in spatial design, using fly-throughs or physical and virtual models: something for designers to bear in mind.

During group activities, the facilitator should continue observing the proceedings, checking that everyone contributes. The process itself can be revealing and the insights it offers can be as useful as the outcome, so it can help to ask questions as participants work on their task to understand their thinking.

Close the session on a positive note with a simple or light-hearted question or two, especially if there were any difficult dynamics. Ask if anyone has any questions before the group breaks up, and outline what will happen to the material from the session, the next steps in the design and decision-making processes, and further opportunities for participation. Thank the group warmly for their time and input, and generally aim to make everyone feel glad they came. Send a follow-up email shortly afterwards thanking participants again, asking for feedback on the experience, and whether they would like updates on the project and future events Add them to the mailing list if so.

7.5 Working with Focus Group Material

Focus groups create a lot of material to consider. It’s a good idea to produce a summary sheet for each session, detailing who was involved, the material collected, the relevant research objectives and questions, topics covered, and any comments on the session. Add this to the data library along with material produced by the group, video or audio transcripts, any photos and the facilitator’s notes.

Download and back up video and audio recordings straight away. Reviewing and analysing these recordings can take time, which should be factored into the programme schedule. It will help if staff who attended can review a recording together and make an initial assessment of the material, which can start to guide the analysis. Before considering what participants actually said, begin by identifying the subjects that seemed most significant: those that kept cropping up throughout the session, that they discussed the most and that sparked intense discussion. Also notice silences, tensions, body language, looks and other non-verbal cues, which can provide useful information and contextualise participants’ expressed views.

Managing data

There’s no standard procedure for analysing the large amounts of complex qualitative material that focus groups produce, but the ‘Quick guide to analysing qualitative data’ gives some suggested steps. Often the first step is transcribing the discussion. This can take a lot of time (it’s normal to spend an hour transcribing ten minutes of speech), so it may be necessary to select material to focus on, guided by the initial review. The time investment is worthwhile when a deeper analysis is needed, to discover the underlying reasons for people’s attitudes or behaviour, for example (and if less depth is needed, focus groups are probably aren’t the best method).

Analysing data

Qualitative data analysis always entails disassembling and reassembling material. This might involve investigating various themes, questions or types of users, but always using the same approach of taking data apart and rearranging it, and noting patterns and linkages that emerge. The disassembly stage involves pulling out everything relating to a subject, then tagging these data chunks with keywords and adding comments as necessary. Then start on the next subject, pull out all relevant chunks, add new keywords and comments, and repeat with all the remaining subjects.

A common approach to this phase in UX is affinity diagramming. This is an interactive visual method of identifying themes within the data, which starts by summarising each comment on a post-it note, and then clustering together comments relating to specific objectives or themes that emerge during analysis (see Figure 7.3). It works well for smaller datasets, short programmes or where there aren’t a wide range of issues under consideration. For large and/or complex datasets, I recommend coding, employed widely in qualitative analysis in social science. This entails creating a structure of categories and keywords to index the data, and then filtering, sorting, and cross-referencing to identify themes and connections. The ‘Quick guide to analysing qualitative data’ gives more detail. Both approaches can be usefully done as a team, using index cards or post-it notes, maps and plans of the scheme, and the results of desk research and any previous engagement work, for context.

Whatever the method, the key tasks are to compare and contrast within the material, looking for similarities and differences, patterns and relationships, consistencies and inconsistencies, and the unexpected and anomalous. Designers and visual thinkers will probably find that sketching diagrams, flow charts, mind maps and so on help in exploring and giving coherence to the data. As visually presented information is more accessible and engaging for many laypeople too, these sketches are worth keeping for future communications. It’s also important to keep questioning throughout this stage. Are we asking the right questions, and the right people? Does this data confirm or contradict findings from other research?

Drawing conclusions

If focus groups are held at the initial stages of a project to understand the general local context, it will be too early to draw conclusions, so it’s best just to summarise the range of topics covered, the main areas of interest or concern, and suggestions for next steps. For focus groups dealing with more specific issues, the interpretation process should be guided by the research questions. It’s important to bring all the relevant content into the interpretation phase, and to resist the temptation to cherry-pick the more interesting material or that which supports a desired outcome. Recalling the validity and reliability imperatives (see section 2.2), analyse data impartially and represent it truthfully. However, remember that focus groups aren’t a microcosm of the wider community, and findings aren’t generalisable; it’s impossible to know whether participants’ views are representative, or how much weight can be given to them. And studies have shown flaws in ‘groupthink’; for example, people can find other group members’ opinions more convincing than the factual information given (Weinschenk, 2011).

Figure 7.3

Affinity diagramming

7.6 Key Points Summary

> Focus groups give insight into people’s opinions, feelings, preferences and experiences, with group dynamics playing an important role in shaping the debate.

The role of facilitator is key; it requires a high level of people skills, as well as an understanding of the local context and the proposal.

A focus group should have a clear aim, reflecting the research objectives with a carefully planned schedule of topics to cover.

Exercise selectivity in inviting participants – they have to be the right people to answer the questions.

Venue and room layout can affect how people respond and interact, and should be chosen with care.

Activities and exercises can complement group discussion and offer different perspectives that talking might not.

Working with the complex data generated by a focus group takes time and skill. It will often need to be transcribed, coded, disassembled and reassembled before any interpretation can begin.

A Quick Guide to Communications

Effective communication starts by putting yourself in another’s position. If you understand where people are coming from, you’ll be able to communicate more clearly, and build trust and rapport.

Respect local knowledge. Local people are the experts on their environment and can offer insight that you don’t have, so ensure there is plenty of opportunity for them to do so.

Be open about the nature of the development and the options for the site. What in the proposal can and can’t be changed, and what the options are, for example.

Get feedback on communications before going live, preferably from non- professionals. Check that information materials, web content, media copy and publicity is engaging and hits the right note.

Proactively reach out to marginalised groups to encourage their participation from the outset. Go and meet them on their own terms first to start a dialogue, and be prepared to work with groups with specific needs separately.

Utilise many communications channels. Maximising selected online platforms is essential, but local print media, posters and leaflets can reach larger numbers of people.

Take care not to present proposals in a way that implies that decisions have already been made when they haven’t. Presenting detailed designs at an early stage of consultations says ‘This is what we are going to do’, rather than ‘This is what we could do.’ Begin a dialogue with the community and get their thoughts before starting any design work whenever possible.

Provide the information people need to make up their own minds about a development from the start, rather than trying to win them over (which can have the opposite effect).

Have visible information about the proposed development around the vicinity of the site, especially for public realm projects, which passers-by and regular users of the space will see.

Use more images and fewer words. Make sure they’re images that are comprehensible to the non-professional, which meaningfully reflect the local area to the people who live there.

Aim for ‘cognitive ease’. Communicate using concepts and illustrations that people are comfortable with. Refer to the familiar, well known and tangible. This helps build rapport and credibility.

All public communications should use clear everyday language that everyone can understand (aim for a reading age of 12). There is no need to dumb down – just avoid jargon, abbreviations, technical terminology, corporate buzzwords and design-speak.

Aim to get a wide range of feedback rather than as many responses as possible. Targeted communications may be needed to engage some groups.

Show empathy and be a good listener. Try to understand the potential effects of the proposed development on local people and listen to their concerns. Ensure they have opportunities to discuss those, even if they can’t be resolved by the design team.

Ongoing communication is essential to build trust and enable continuing discussion. A report on the event, articles in the local press, a newsletter, a dedicated website, social media or a liaison group for bigger projects can facilitate this.

Get feedback on communications whenever possible. For example, ‘What do you think of our website?’ and ‘How did you find completing this survey?’ and act on the responses.