Chapter 05 /

Participative Building and Materiality: Scarcity of Resources and a Platform for Communication

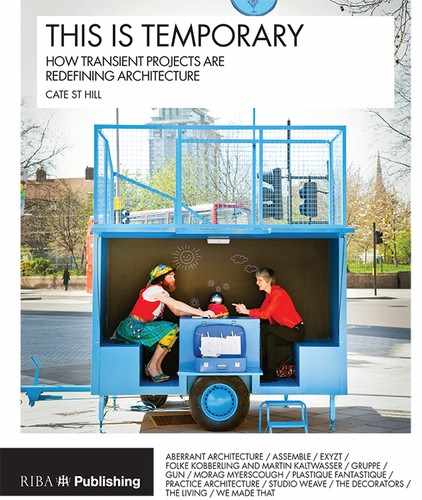

FIGURE 5.1: previous / the Emotion Maker, an inflatable structure by Plastique Fantastique at Clerkenwell Design Week in 2011

INTERVIEWS: FOLKE KÖBBERLING AND MARTIN KALTWASSER [GERMANY] / PLASTIQUE FANTASTIQUE [GERMANY]

When a structure is only around for a short amount of time, what it’s made of and how it’s made can become incredibly important. One-off installations can initially seem like a waste of resources, and the consideration of what’s going to happen to the materials afterwards all too often an afterthought. But, as the saying goes, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure: from scrap material and found objects to blow-up bubbles formed in a matter of minutes, this chapter looks at how two practices are using materials to gather and empower people to think about sustainable, self-initiated ways of building.

Interviewed in this chapter, Berlin-based artist duo Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser, in their own idiosyncratic way use throwaway objects and discarded materials, found and collected themselves, to create ad hoc, self-built urban interventions. Using very few resources – a hodgepodge of timber pallets, bulky refuse, hand-me-down stage sets and junk picked off the street, obtained from local building sites or donated by friends and neighbours – these improvised, site-specific projects comment on issues ranging from consumption and grass-roots participation to sustainability and the scarcity of resources. Often assembled by a close-knit team of volunteers and students, on derelict urban sites and the last few remaining gaps in the city with unrestricted access, they’re examples of empowerment – a call to action for collaborative, collective, participatory design. Against a backdrop of the privatisation of public space and surveillance, these impromptu structures also share a social concern for facilitating spontaneous encounters in urban public spaces. In their 2009 book Hold It!, Köbberling and Kaltwasser comment: ‘Our projects seek to challenge conventional and tendentiously backward-looking approaches in planning and building, conditioned by social segregation, and formally executed in an architectural language that idealises historical precedence. Using a build-it-yourself approach to set up constructions and buildings made from found surplus and reject materials, we are positing alternatives in experimental, open and communicative urban planning strategies that transcend familiar eurocentrist and historical concepts.’

FIGURE 5.2:above / the Jellyfish Theatre by Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser was a temporary theatre created on a school playground in Southwark for the Oikos Theatre Festival in 2010

Their projects take on a form of their own, shaped by the back-to-basics building process. As they explain in the interview, with little, if any, fixed technical drawings or models to guide them, structures are literally made up as they go along, often dependent on what materials are available to hand. ‘We always go with the material,’ Köbberling says. ‘We never create models because we don’t know what the thing will look like. You can shape it a little but you never know how a façade will look until you’re there. A lot of people don’t like that process because it’s so situationalist, a little bit chaotic and much more time consuming.’ Adds Kaltwasser: ‘After having completed the basic structure we make the cladding, the building of walls, doors and interior design from found material. In this stage of building we act very freely, very sculptural.’

The Jellyfish Theatre, for example, was a squat, spaceship-like temporary theatre created on a school playground in Southwark over one summer for the Oikos Project and the London Festival of Architecture in 2010. Built by more than 100 volunteers, it was the first theatre building in London made completely from scrap material. The 120-seat construction, made of discarded theatre sets and hundreds of humble timber pallets sourced from New Covent Garden market, hosted a series of climate change-based plays drawn up by The Red Room Theatre Company. Without any electricity on site, uncut pallets, sheets of wood and old doors were hammered haphazardly by hand onto a steel structural frame, gaining a life of their own and seemingly exploding out behind the dressing rooms to form the ‘tentacles’. ‘The bankers and businessmen passed by our stone-age site construction site and they could feel and smell that we were the nicest, best, most enthusiastic and funniest construction site in the whole of London!’ enthuses Kaltwasser.

Another project, Amphis, is an octagonal, two-storey theatre, also made of discarded materials, created in just six weeks by 40 volunteers on the site of Wysing Arts Centre in Cambridgeshire in 2008. The 6m-tall structure was built on a falsework made from pallets and timber beams, filled with compressed sand and rubble because concrete was too expensive.

FIGURE 5.3: above / the Amphis Theatre coming together, with the help of 40 volunteers

Rejected material, including teak, came from nearby Cambridge University, while the large central timber-panel ground floor had previously served as a stage dance floor. Its black lino surround was made from discarded college worktops. Says Kaltwasser: ‘As soon as we start a construction, we communicate a lot with passersby and visitors, and then a snowball effect starts. After a short time, everybody knows we need material and sometimes we are literally overflooded with free building material.’ Now that it has become a favoured refuge of local birds of prey, due to several openings that cannot be shut, the structure still stands, five years after it was supposed to be dismantled. ‘The thing with temporary structures is that you can experiment more and then you think, “Yes, this is really working, let it stand there”,’ says Köbberling.

FIGURE 5.4: above / inside the Emotion Maker by Plastique Fantastique, the stark white bubble created a reflective, intimate experience

However, Köbberling and Kaltwasser reveal in the interview that they are finding it increasingly difficult to create these ad hoc structures due to more and more rules and regulations putting constraints on experimentation and improvised designs. There are very few sites in our cities now that can be built on at a whim, without permissions or planning consents; the architect or designer has less opportunity to work autonomously, but often needs to involve the city, municipal controls, institutions and organisations. Overly cautious health and safety nets also mean that projects need to be thoroughly planned and vetted before they are built. Indeed, it is interesting that Köbberling and Kaltwasser are now going their separate ways, because for Köbberling: ‘The freedom of creating is missing and then you are totally into architecture. You cannot work with the material any more. If you don’t like something, you cannot just exchange it.’ Plastique Fantastique, meanwhile, has made its name by sticking religiously to just one building material – polyethylene, otherwise known as plastic. Its approach was first developed when founder Marco Canevacci was faced with the task of heating an empty factory he had rented in Berlin. ‘It’s quite a cheap material; you can easily seal it and create these kind of basic bubbles,’ explains Canevacci in the interview. ‘We filled it with warm air and that was it. They were the first rooms we produced, in 1999. That was the beginning, and afterwards I realised the potential of designing these kind of architectures. I think there’s something magical about a structure popping up in 20 minutes and at the same time disappearing as fast as it inflates itself.’

It’s the immediacy that excites Canevacci: ‘I’m interested in this because standard architecture takes a really long time to express yourself and after a couple of years you might have something different in your mind.’ These inflatable or pneumatic structures play with the potential of urban context, augmenting our perception of the city and animating the senses by squeezing themselves into narrow streets or inside buildings. Seemingly space-age and slightly alien in nature, they also play with transparency, fluidity, surfaces and layers. At the same time, they demand interaction and engagement from their users. ‘Most of our installations are quite playful works [which] creates a communicative environment at once. It’s a public thing, because people who don’t know each other start to interact, communicate and interchange the experience you may have in this context,’ says Canevacci.

FIGURE 5.5: above / Aeropolis, a project for the Metropolis Festival 2013 in Copenhagen, took one pneumatic structure around 13 different locations in the city

The Emotion Maker at London’s Clerkenwell Design Week in 2011, for example – a collaboration between Plastique Fantastique, sound designer Lorenzo Brusci and musician Marco Barotti – created a temporary performance chamber that housed an all-consuming, interactive sound installation. Participants were able to pick and choose from hundreds of music samples to create a composition of their own, while the stark white of the bubble created a reflective, intimate atmosphere that aimed to break down the formalised boundaries between people and their participation within a public space in the city. Says Canevacci: ‘Only two people were allowed to enter the installation at one time, it took 10 minutes, and the experience inside was always a different one. It’s funny because in most cases the two people didn’t know each other.’

While that project placed the inflatable structure in an open public square, another project, Sound of Light (2014), pressed the bubble into the tight confines of an existing building, a 19th-century music pavilion in Hamm, Germany. ‘If you take it as it is, it’s just a geometric shape, but if you try to squeeze it into the existing environment it starts to change its shape and become something different, something you can apply to endless situations,’ says Canevacci. Because the original pavilion in which it was constructed is relatively open, with two parallel rows of slender columns, the inflatable structure bulged out of all the gaps in between, giving the appearance of a rather strange silver worm ready to burst its seams. In just a few minutes, Plastique Fantastique had altered not only the existing architecture but the people’s perception of that ordinarily open space, creating a totally new form and context. ‘The structure is actually a tool to play with the urban landscape, so you use the bubble as a tool and then you have to add something on to it… like an installation,’ explains Canevacci. In this case, Plastique Fantastique used a digital camera to transform sunlight into audio frequencies, effectively creating a ‘giant vibrating loudspeaker’. Six hanging, coloured, inflatable ‘columns’ received the different frequencies from the sky above and converted the input from visible to audible via a series of woofers. By flooding the senses with colours, shapes, sounds and vibrations, Plastique Fantastique orchestrated a transitory dream-like experience, an altered reality transporting users to a new, never-experienced-before place.

At first glance, plastic might not seem like the most sustainable option. Yet, while temporary architecture raises serious concerns about reuse and recycling – often seen as quick, sporadic bursts of resources that are then quickly dismantled and thrown away – Plastique Fantastique’s inflatable structures create endless possibilities for shapes, forms, and ultimately experiences, each new, spontaneous situation being entirely different from the one that went before. They can be reused time and time again to form a whole host of diverse, weird and wonderful urban interventions. Indeed, now Plastique Fantastique believes their potential can be more fully realised by focusing on placing these impromptu structures between existing buildings, narrow streets or squashed under highways, rather than the bubbles creating their own shapes in open spaces. ‘You can place a bubble in a narrow street and it changes its shape and the street changes character as well. You don’t have the street itself, you have something in between that is offering an experience or some weird shapes,’ notes Canevacci. As such, it’s about creating an open dialogue between users of the city and public space – a reinterpretation of the formal boundary between exterior and interior.

A project for the Metropolis Festival 2013 in Copenhagen, called Aeropolis, for instance, took one pneumatic structure around 13 different locations in the city. The same material adapted itself and changed shape depending on the location, from a silent disco at a noisy intersection of the city, to meditation and yoga sessions by a lake. These inflatable structures, dotted around our cities, could almost be seen as flash mobs, bringing people together when all too often we barely swap eye contact, let alone interact, on our urban streets.

Each practice, Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser, and Plastique Fantastique – incidentally both from Germany – use materiality in two unique ways to facilitate experimental, open and communicative design processes, empowering imaginative, spontaneous, new encounters in urban public spaces. Both invite audiences, especially students, to help during set-up, motivating and inspiring them to think about the city in alternative ways, while also using the structures as a platform, or indeed catalyser, for debate and free-flowing conversation between various participants during their short-lived manifestation. As Köbberling and Kaltwasser say: ‘The built environment should be everyone’s concern. Architects and artists could help to convey how to do things yourself, how to experiment and how to harness creative potential. This could be just the trigger.’

FIGURE 5.6: previous / the entrance to the Jellyfish Theatre

Interview 10 / Köbberling / Kaltwasser

MARTIN KALTWASSER / FOLKE KÖBBERLING

Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser are an artist and architect duo based in Berlin, Germany, who have been working together since the late 1990s. They use discarded material and found objects to create projects in public spaces that question issues such as our pressure to consume, growing surveillance and the ever-increasing motor traffic that is threatening to change the appearance of our cities in a fundamental way. They have lectured extensively in design schools in Germany as well as the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design in Vancouver, the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, the Technical University of Vienna and Chelsea College of Art and Design in London. They are now going their separate ways to concentrate on different interests.

How did you start working together and what made you decide to use throwaway objects and discarded materials in your projects?

Folke Köbberling: In 2002, a long time ago now, we were asked to do a lecture evening in the Volksbühne – a theatre on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz in Berlin – and an exhibition on the informal housing in Istanbul. We did a lot of theoretical research and got really familiar with their construction techniques and the law, which comes from the Osmanian times, there, that you can build a house overnight. In Turkish it is called ‘gecekondu’ (from ‘gece’ meaning ‘night’ and ‘condu’ meaning ‘house’). In the end we thought we would like to take this experience back to Berlin and see what the reaction would be like. We started to look for a space and found one in front of Gropiusstadt, a totally planned area in Berlin where 600,000 inhabitants live.

We thought it would be nice to build there and have all the surrounding high-rise buildings look down on us, like an annex almost, so that it would have a similar feeling to the housing in Istanbul. We looked on a construction site in the middle of Berlin for scrap material and beams. The size of the materials was the base for the construction. In the end we built a house overnight, with all its difficulties of lack of light and power. In former times, and still now, we use almost always scrap materials, even for our own homes – you just use what you can get in the street.

FIGURE 5.7: above / Hausbau was an entire family home built on a disused meadow overlooking a housing estate in 2004

What was the reaction to that first project?

FK: Everybody in the high-rises could see us building the house overnight and the reactions were very positive. The people living there had to walk past us every day and because we lived there with our two children, there was already a level of communication. We used this temporary structure to connect with people and talk about housing and sustainability. Were they alienated in their high-rises or would they like to have a house like we had there, even though it was only very temporary, even though it was only standing there for one week?

So in 2005 we planned it over a longer time and invited friends and students to do a bigger settlement. We looked and collected material for three months, which we exhibited in an exhibition space before we started to build six individual buildings by six different architects and city planners. We wanted to see what would happen if nobody communicated with each other; it was an experiment in how city planning works if you don’t talk, if you never have a meeting. It was really interesting because we all didn’t really react to each other: everyone just looked for the best place, and in the end the settlement was very spread out.

Also, we wanted to get in contact again with the community of the Gropiusstadt. We were there the previous year and now we came to the site with many more people. So the barrier for the people of Gropiusstadt to cross was much higher than the year before. Afterwards we took the material down and brought all the scrap material to the

FIGURE 5.8: above / Hausbau was made of discarded timber found on Berlin’s many building sites

FIGURE 5.9: above top / Musterhaus (Model House) was a one-family prefab home built in front of the Martin-Gropius-Bau museum in 2005

FIGURE 5.10: above bottom/material found for free throughout Zürich was sorted, stacked and displayed on the eighteen shelves of Köbberling and Kaltwasser’s buildings materials centre

Martin-Gropius-Bau, a museum, where we built a project called the Musterhaus on the parking lot. Built on a green area of the Martin Gropius Bau premises in Berlin, the Musterhaus (Model House) is a one–family prefab model house. In its cube shape it rather resembles the T–Com House, a high-tech house, which a manufacturer of prefabricated houses had put on show in central Berlin to advertise the delights of suburban life.

In contrast to this, we made the Musterhaus from materials widely available on Berlin’s streets, disused lots and building sites: bulky scrap, used materials, random finds and construction waste. The Musterhaus, just a stone’s throw from Potsdamer Platz, formed a marked contrast to the Berlin monoculture of block buildings and the rigid plans for the city’s urban development.

How easy is it to get hold of discarded materials for your temporary projects?

FK: I would say we really became experts in finding material. You look for materials in each city, on the street. If you also think about fairs and biennales, you already know there will be millions of booths, where people come, build something, and end up with 90% of the material in the trash. We really try to make the logistics transparent. We lectured at the Berlin University of the Arts in 2008 and tried to make an internet platform where the leftover material from installations and structures at fairs could be made available, free, for everybody. Unfortunately we did not have enough resources to make it work, but nowadays there are more platforms that specialise in scrap material.

In the UK we have websites such as Freecycle for domestic objects, but I wonder whether, like you say, there should be a similar platform for discarded material from exhibitions or the temporary structures being discussed in this book.

FK: Exactly. We tried to really make it professional because there are so many exhibitions and exhibition constructions, but they have to come down at the end, and you can count on this. If you go on the street or a construction site, you never know what you will find.

There is also a difference in finding materials in different cities. In Berlin it’s very hard because everybody takes material from the street, but in Munich it’s easier because they’ve been building more – there it’s a paradise. Then, for example, in Zürich it’s really difficult because when you go on to a construction site they’re very efficient with materials. On the other hand, they are also tearing down whole areas of cities.

Let’s talk about the Jellyfish Theatre at Union Street in London’s Southwark, produced for the London Festival of Architecture 2010. How did that project come about?

Martin Kaltwasser: This was in collaboration with The Red Room Theatre Company, who went through the whole country looking for temporary structures and found our previously built theatre, Amphis, at Wysing Arts Centre in Cambridge. The idea was to create a temporary structure to host the Oikos Project, the first theatre festival in the UK to thematise climate change. It was also part of the London Festival of Architecture, organised by the Architecture Foundation, where visitors from all over England took part in building parts of the theatre in a two-day workshop.

The Jellyfish Theatre became the first theatre building in London completely built from scrap material. We chose the name because the jellyfish is both one of the most poisonous and the most beautiful creatures on Earth. The theatre was built by more than 100 volunteers in the shape of a jellyfish – with an organic body and tentacles. The use of found and recycled material, using hand tools, the minimal budget, and endless fun with building, joking and creating – all in the neighbourhood of one of the world’s biggest financial centres – was a totally outstanding experience.

It was incredible because it was built in Southwark while the Shard was under construction. The bankers and businessmen passed by our stone-age construction site and they could feel and smell that we were the nicest, best, most enthusiastic and funniest construction site in the whole of London! The Jellyfish Theatre was mostly made out of pallets, which we got from the New Covent Garden Market as well, and old theatre sets, event sets and a lot of private material donations. It’s our experience that as soon as we start a construction, we communicate a lot with passersby and visitors, and then a snowball effect starts. After a short time, everybody knows we need material and sometimes we are literally overflooded with free building material.

Did you ever return to the project after it had been completed and was being used as a theatre? Are you often involved in the events programme that accompanies your temporary structures?

FIGURE 5.11: above / the Jellyfish Theatre was made of discarded theatre sets and hundreds of humble timber pallets sourced from New Covent Garden Market

MK: It’s different for each project. For the Jellyfish Theatre, Red Room organised the Theatre Festival and, together with the Architecture Foundation, the application for the whole building permission. It is completely different now with the Ding Dong Dom, which is the younger sister of the Jellyfish Theatre. The Ding Dong Dom is a temporary theatre in the middle of Berlin, which we started building in summer 2013 in collaboration with the avant garde performance group Showcase Beat Le Mot on the site of the Holzmarkt, near Alexanderplatz. It is a work-in-progress situation: the theatre will not be completed until 2016 or thereabouts, but in May 2014 the Month of Performance Art took place in the ‘unfinished’ space, which had already a roof, and walls made out of more than 400 recycled windows – so it was a glass house. Many events, happenings and performances took place that summer of 2014, because everybody who came there was totally enthusiastic about the non-perfect setting, the unfinished situation, which seemingly motivates and inspires people more than a perfect situation. Therefore you can say that the perfect situation is the construction site. Maybe this is much closer to our experience in life than perfect settings.

FIGURE 5.12: above / the Jellyfish Theatre was formed organically by hand, with limited pre-prepared plans or models, and exploded outwards behind the dressing rooms to form the ‘tentacles’ of the jellyfish

FIGURE 5.14: above bottom / section through the Jellyfish Theatre

The Amphis in Cambridge, which you made in 2008, is still there. Would you say, then, that it is temporary or permanent?

FK: Well, this is the funny thing, it only had a permit for two years. After that two-year period it was still in really good condition – and also we have to say that it is on private land. It’s a really beautiful theatre and it has an incredible acoustic quality that no one knew about when we were building it; they have a lot of musical festivals in August and the director said she loves the acoustics because it’s like a dome or a church.

If took us three weeks just to do the ground work because we made it double the size than we first thought. It's really polished because we got incredible materials. We got a lot of teak wood, mainly from the colleges: half the façade is made of teak, as well as the floor and beams. People just brought us incredible materials. The thing was that an owl also made it his home, so we weren't allowed to take the structure down. It’s now under this protection somehow and nobody asks any more. Now it’s permanent but it was never meant to be. Maybe we would have built it differently had we known, but the thing with temporary structures is that you can experiment more and then you think, ‘Yes, this is really working, let it stand there.’

Is that perhaps why temporary structures appeal to you – because you like to experiment, and because you also build the structures yourselves, you’re almost making it up as you go along?

FK: We always go with the material.

MK: Of course we make drawings, create an idea about the structure, make plans – sometimes less precise, sometimes very detailed – and then we build a basic skeleton for the theatre, the house, the shelter. This basic skeleton structure is mostly built from, solid timber, mostly new, bought material, or we even use scaffolding as the basic structure (as we did for Jellyfish Theatre, Ding Dong Dom and Musterhaus). Then after having completed the basic structure we make the cladding, the building of walls, doors, and interior design from found material. In this stage of building we act very freely, very sculptural.

FK: We never create models because we don’t know what the thing will look like. You can shape it a little, but you never know how a façade will look until you’re there. The Jellyfish Theatre was supposed to look totally different; some things didn’t work or they weren’t allowed, or you suddenly find a different material. For the Amphis Theatre in Cambridge it was also like this: we had volunteers and they created the façade. You never know how it’s going to turn out until the end.

Is the appearance of your temporary structures important to you?

FK: Somehow it’s always a struggle because of course it’s important what it looks like, especially from inside, but sometimes you have to make compromises, or sometimes it’s really hard and you have to rework elements.

Do you see these temporary structures as art, installation or architecture, or something in between?

FK: I am an artist. My role was really to look for a site or for materials. Maybe you don’t have to see it as art or architecture; maybe it’s an effort to create something that you would like to have in a city, maybe you don’t need this big planning permission. In Germany we have this word

FIGURE 5.15: above / the structure of the Amphis Theatre was built on a falsework of pallets and timber beams, filled with compressed sand and rubble because concrete was too expensive

FIGURE 5.16: above top / Amphis Theatre is an octagonal two-storey theatre on the site of Wysing Arts Centre in Cambridgeshire made of discarded materials, built in 2008

FIGURE 5.17: above bottom /part of the façade of Amphis Theatre is made up of old salvaged doors and windows

‘Möglichkeitssinn’ that means the sense of possibilities or opportunities – that something is possible but you would never have thought it. For example, with the Jellyfish Theatre, it was just, ‘Wow, here is a structure for £5,000, standing right in front of the Renzo Piano building which costs billions.’

Are there any constraints or challenges to a temporary project?

FK: The more regulations we have, the more you have to calculate everything and in the end it becomes impossible to work with recycled material. As soon as a project gets a special status and becomes more public, we cannot take responsibility any more, or an institution can’t take responsibility, and as soon as it goes to the municipality, it’s really difficult because then who takes responsibility?

In fact, I don’t want to do this any more and Martin is going more and more in this direction, because for me, the freedom of creating is missing and then you are totally into architecture. You cannot work with the material any more. If you don’t like something, you cannot just exchange it. If you have a planned building, everything is clear, but as soon as you work with the material it’s a totally different process. A lot of people don’t like it because it’s so situationalist, a little bit chaotic and much more time consuming. On the other hand, what we’ve always said is that you’re getting structures you never expect, because all of a sudden the structures form. Sometimes it’s just down to coincidence. If you have a totally planned process you’ll never have those coincidences.

FIGURE 5.18: above / discarded material picked up from the streets of Zürich was used to create this site-specific ‘palais’ in 2007

FIGURE 5.19: above / with its wide, overhanging roof, the structure became a popular meeting place in this Zürich square

FIGURE 5.20: previous / the shape of Aeropolis was able to adapt around existing structures and squash itself in between trees and lamp posts

Interview 11 / Plastique Fantastique

MARCO CANEVACCI

Plastique Fantastique is a Berlin-based platform for temporary architecture, founded by Marco Canevacci, which samples the performative possibilities of urban environments. Established in 1999, Plastique Fantastique has been influenced by the unique circumstances that made the city a laboratory for temporary spaces and has specialised in creating pneumatic installations as alternative, adaptable, low-energy spaces for temporary and ephemeral activities. The transparent, lightweight and mobile shell structures relate to the notion of activating, creating and sharing public space and involving citizens in creative processes. At the moment Plastique Fantastique develops project-oriented teams to realise a wide range of projects worldwide, from London’s Clerkenwell Design Week to a recent teaching workshop in Cyprus.

How did you start Plastique Fantastique?

Marco Canevacci: The real beginning was in the early 1990s. I moved to Berlin in 1991 and I was studying architecture at the technical university. At the same time I was quite impressed with the underground life there: you had this special sensitivity about temporary spaces since the East German state collapsed, so everybody was proposing a mix of cultural and hedonistic activities in all the abandoned areas you might find in the middle of East Berlin, which were quite a lot. I had come from Rome, which was quite the opposite situation.

At the end of the 1990s I finished my studies and rented an empty factory of 2,000 sq m in the area of Friedrichshain. Since it was impossible to heat it, I, together with some friends (Michael Heim, Pietro Balp, Raffaele Distefano), started to make some bubbles and fill them with hot air. That was the beginning of the experience. Nowadays I work very closely with a musician (Marco Barotti), a sculptor (Markus Wüste) and a designer (Yena Young).

What drove you to work with plastic and these inflated forms?

MC: Actually, it was this situation: the necessity of having a warm place inside this big factory. Plastic – I’m talking about polyethylene – is quite a cheap material; you can easily seal it and create these kind of basic bubbles. We filled it with warm air and that was it. They were the first rooms that we produced, in 1999. That was the beginning, and afterwards I realised the potential of designing these kind of architectures and we started to move around Europe doing different installations.

So the name Plastique Fantastique came out of what you were creating?

MC: The name itself was actually the name of the first installation we did in our empty factory, which in the end transformed itself into a techno club called Deli an der Schillingbrücke. Since then we have kept the name.

What interests you about temporary architecture? Are all your projects temporary?

MC: I think there’s something magical about a structure popping up in 20 minutes and at the same time disappearing as fast as it inflates itself, so you can create an extra architecture in a public space that exists for a limited span of time. I’m interested in this because with standard architecture it takes a really long time to express yourself and after a couple of years you might have something different in your mind.

How do you hope people react to these structures? What do you hope their experience will be?

MC: Most of our installations are quite playful works, so people actually get quite relaxed and start to play within the one they are in as well as outside the bubble. So it creates a communicative environment at once. It’s a public thing, because people who don’t know each other start to interact, communicate and interchange the experience you may have in this context. Of course you can add different layers, performances, audio systems, projections and so on to enhance a project itself.

FIGURE 5.21: above / a gold ring wrapped itself around a building for the Kunst- und Kultur Festival in Berlin in 2011

Let’s talk about the The Emotion Maker at Clerkenwell Design Week in 2011. How did that project come about and what was the idea behind it?

MC: The project was first of all a collaboration between three people: myself, a sound experience designer called Lorenzo Brusci and a musician, Marco Barotti. We wanted to offer a concert which was always changing, so you enter the structure and you can choose from 15 different instruments playing hundreds of music samples pre-recorded by different musicians to create a composition of your own. Only two people were allowed to enter the installation at one time, it took 10 minutes, and the experience inside was always a different one. It’s funny because in most cases the two people didn’t know each other: you have to put your name on a list and then you go inside with the other person. Sometimes we had wonderful concerts, sometimes it was weird, anyhow it was always different.

How much are you involved with the events programmes that go along with your structures? Is that an important side of the project, what goes on during the time the structure is up?

FIGURE 5.22: above / the Emotion Maker housed an all-consuming, interactive sound installation that could be experienced by only two people at a time

MC: The structure is actually a tool to play with the urban landscape, so you use the bubble as a tool and then you have to add something on to it. It can be something like an installation, but it can also be a banquet – you could just invite the neighbours to cook something inside and share food together. We did this project in 2014 called Sound of Light and in this case we offered a synesthetic approach to experiencing light as sound, so basically there is this opaque pneumatic architecture, and once you are inside you have light coming through six different hanging columns, each representing a basic colour: cyan, magenta and yellow, and red, green and blue.

There is a camera mounted on the rooftop of the structure – a music pavilion in Hamm, Germany, that we squeezed the installation into – which films the sky and divides it into the six colours. The output is transformed into sound and converted from visible to audible sensory input. At the bottom of each column, a woofer reacts directly to the sound and the lighting conditions, converting the whole architecture into a giant vibrating loudspeaker.

What happens to your projects afterwards? Do they get reused?

MC: It depends. We have been trying to re-present Sound of Light in different locations, but we have to change it in order for it to fit in other places. It was a fun idea to place it inside a former music pavilion in Germany, a building of 1912, and now we are proposing it in a different context. For example, one is in France, where they also have different music pavilions. We would like to include all of it inside a major structure, so the pneumatic structure sits around the music pavilion, you have to enter it and it becomes a new vibrating architecture – something unusual and something new.

There are projects that we’ve done that have been reinterpreted for other conditions, and

FIGURE 5.23: above / the Emotion Maker broke down the boundaries between strangers and the public space within a city

FIGURE 5.24: above top / Sound of Light placed an inflatable structure into an early 20th-century music pavilion in Hamm, Germany in 2014

FIGURE 5.25: above bottom /Plastique Fantastique used a digital camera to transform sunlight from the sky above to audible frequencies with a series of woofers

there are basic geometrical forms that you can use several times. During the Metropolis Festival 2013 in Copenhagen, we had an installation called Aeropolis. The pneumatic structure was designed with two optional tops (one mirrored and one transparent) to allow maximum mobility and flexibility during its tour through 13 different locations around the city. It offered a communication platform for experiencing a sequence of activities with changing scenographies, all curated together with local cultural institutions: astronomy between two climbing walls in Nørrebro, kindergarten and hip-hop hop in front of a supermarket in Valby, meditation and yoga by a lake in Vanløse, performances at Islands Brygge, martial arts at Superkilen, lectures in Amager, a silent disco at one of the noisiest intersections of the city in Nordvest... If you take it as it is, it’s just a geometric shape, but if you try to squeeze it into the existing environment it starts to change its shape and become something different, something you can apply to endless situations. So I’m more interested in squeezing or pressing or playing with the local context than in placing a bubble in the middle of a square.

Do you mean inside a building, rather than in a public space like a street or a square?

MC: I’d rather try to play with the neighbourhood, with the existing buildings or trees or bridges, than place it on a square. I always try to change the shape and the environment itself by having a contact. You can place a bubble in a narrow street and it changes its shape and the street changes character as well – and you can do that in a couple of minutes, half an hour maximum.

That probably also changes a person’s perception or experience of that street or space.

MC: You can wake up, go out and your street has changed, you don’t have the street itself, you have something in between that is offering an experience or some weird shapes.

Do you notice a difference depending on where or in which country you place these structures? Do people react differently in different cities?

MC: Yes, of course. You may have different reactions if you work in the south of Europe or in Scandinavia, but I always realise that there is some basic stuff that doesn’t change. People are always interested in it, they come and ask, and once you’ve asked them to come and experience the installation, they do it. The feedback we get is mostly good and it’s something that’s always quite interesting. Every time we do these projects there is no aggression wherever we work – in Berlin, in Spain. We also always invite people to help us during the set-up, the dismantling and the installation itself, so it’s quite important to be on site, to invite people to check out our work and to deal with it.

FIGURE 5.26: right / the transparent bubble of Aeropolis popped up around different locations in Copenhagen in 2013

FIGURE 5.27: above top / a boxing match takes place outside one of the Aeropolis’s locations in Copenhagen

FIGURE 5.28: above bottom / Aeropolis was made of fireproof PVC, with industrial ventilators to keep the shape blown up

Nowadays we are making lots of workshops, mostly with students, and of course with people that are just passing by. Maybe they get interested and we make a quick introduction about how to use this kind of architecture – the easiest way is to get plastic film taped altogether, then you just need a normal ventilator and that’s it, so I think it’s quite good to offer the basic knowhow to let people create these structures by themselves.

Do you think temporary architecture is becoming more popular with students? What advice would you give to a student wishing to go in a similar direction?

MC: At the moment there is a big revival of all those kind of utopian approaches of the 1960s. I think that most of the architecture or design universities are trying to reapproach this way of working with temporary architecture and inflatable architecture is one-fifth of that, so it’s quite popular. I had a workshop in Cyprus last November, and next week I’m going back to produce, with students, three different structures that will be going around the island of Cyprus over two and a half weeks. We also had an open call with local artists to play with those bubbles.

What else does the future hold for Plastique Fantastique?

MC: There are three main directions. One is all the experiences I am making with students within universities – workshops and the like. The second one is the more artistic projects, for example getting invited to a festival and having the freedom to develop anything you want. And thirdly, there are the more commercial projects, where you just make a commitment to build an installation for an event, fair or presentation. Then there are the collaborations, with different artists and professionals.

What would be your dream project?

MC: To make a science fiction movie with Quentin Tarantino! That’s a good brief isn’t it? I love his movies, because they’re quite ironic and this is my approach. There are lots of directors I would like to work with but I think I would like to work on fiction. When you work with a camera you can choose what to film and what not to film. When there is a performance on a stage or in one of our structures, the public can see everything, but with a camera you choose what people look at.

FIGURE 5.29: opposite / a pneumatic sound installation, titled Space Invaders, is installed between two buildings in the Mitte district of Berlin in 2008