Conclusion /

CATE ST HILL

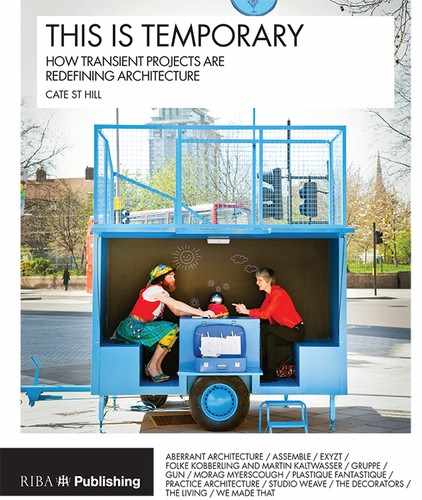

For years now, the word pop-up has been bandied about, implying a circus of tricks used to advertise and popularise, to provoke spectacle and pageantry, to create an immediate, photo-ready frenzy. In its simplest form, temporary architecture can be trite, quick and cheaply put together – but this book has shown that there is a group of imaginative, original, young architects and designers who are creating more intuitive gestures in the built environment, backed up by rigorous research, community engagement and much deeper social ambitions. They’re making studied responses to contemporary lifestyles and changing cityscapes, and in the process they’re causing a subtle but profound shift within the architecture profession. Alternative modes of practising architecture are invariably emerging from temporary architecture, ranging from multidisciplinary, research-based design to collaborative, participative building and self-initiated, self-built projects. In these cases, the role of the architect is expanding to include storyteller, historian, urban planner, psychologist, facilitator and communicator. Collaborations are further blurring these boundaries. Neither is it always necessary to go through the traditional rigmarole of architectural education any more.

One concern highlighted in the book is what happens to the materials of these structures once their temporary existence has ended. Some architects had designed projects to be dismountable and reusable; some had components still dotted around their studios and back gardens waiting for the next opportunity; others didn’t know what had happened to their structures at all. ‘What I think is a bit of a shame with temporary architecture is that there’s no recycling process,’ notes Aberrant Architecture’s Kevin Haley. ‘At the end of Clerkenwell Design Week, if we had said no, we didn’t want the Tiny Travelling Theatre, they were literally just going to bin it.’ While across the world there are grass-roots online platforms such as Freecycle that allow people to give (and get) domestic paraphernalia for free, perhaps in today’s throwaway society there should also be a similar initiative for discarded material, not just from temporary architecture, but from exhibitions, arts fairs, theatre sets, music festivals and so on – something that Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser tried (unfortunately unsuccessfully) to do in 2008. For the most part, though, the architects and designers here didn’t see their projects as wasteful throwaway objects, but meaningful investments into a space or into the development of longer-term ideas.

Also looking past the impermanence of these projects, another fundamental question that came up time and time again throughout the interviews was that of what we define as temporary. How long is temporary? Is it five minutes, six months, a year? Or could it be 20 years, even 100 years? Many of the projects included in this book have indeed stayed in place far longer than their initial time frame proposed. Morag Myerscough’s Movement Café was meant to be in Greenwich three months but lasted a year; Studio Weave’s Paleys upon Pilers had planning permission for six months, but stayed for two years; Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser’s Amphis for Wysing Arts Centre in Cambridgeshire was likewise supposed to be around for two years, but has stayed for eight; Practice Architecture’s Frank’s Cafe has reappeared each summer since 2009; and EXYZT has returned to the same vacant site in Southwark three times over a period of seven years. Meantime, Aberrant Architecture is working on a public arts commission in Swansea that is purportedly permanent, but will only be there for 20 years. Similarly Studio Weave’s Lullaby Factory at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London will be in position for 15 years.

In fact, many buildings in our cities that were meant to be short-lived have stayed – the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the London Eye and the Millennium Dome in London, and the postwar prefabs from south London to Newport, Wales, to pick just a few examples. The Serpentine Pavilions are sold after each summer turn, and have been transformed into beachside restaurants, private garden follies and a theme park marquee. Many of these constructions (in our public spaces) would probably not have been approved if they had been permanent from the outset: people are wary of anything new that might make mistakes and blight our cities – but once we get used to something, we become attached to it and hate to see it disappear. As Studio Weave’s Eddie Blake suggests in Chapter 3, ‘That’s to do with people thinking they’re going to hedge their bets and just say it’s temporary – they get to like it and it’s actually a scary decision to say, “This is going to last a hundred years.”’

Perhaps it’s time to rethink the dividing line between temporary and permanence. Perhaps it doesn’t need to be so prescriptive and portioned off into categories. ‘Short-life projects can be a great way to test an idea that can then grow in strength, demonstrate itself, and potentially evolve into something more permanent,’ says Practice Architecture in Chapter 4. ‘Over the years, our ideas about what the space of impermanence means have gone through quite a shift. We have an increasing desire to make things that are solid, embedded, invested – that have longevity and that represent an investment in and expression of a geographical community.’ Indeed, just because temporary architecture is only around for a short time, that doesn’t mean that it can’t be as considered as something more longer-term. The projects shown here have the ability to catalyse subtler and wider-ranging effects, as shown for instance by The Decorators’ project for Chrisp Street Market. That scheme, which involved setting up a ‘Town Team’ to meet regularly, as well as more tangible changes such as new market furniture, has gone on to act as a pilot for two other attention-starved London markets in need of rejuvenation.

As the projects in this book illustrate, temporary architecture can do all the things permanent ‘bricks and mortar’ architecture can do, and more besides: it can test new technologies and materials, it can be innovative and experimental, it can be sustainable, reusable and recyclable, it can enrich and engage communities, and it can help foster a sense of place. And all of this without the risk and constraints of permanence: if it’s a mistake or doesn’t work, then just dismantle it and think again. It’s not that much different from the demolition of the 1960s and 1970s Brutalist monoliths, 10, 20, 50 years after their construction. In this way, temporary architecture may not seem like a waste of resources at all.

The interviews in this book have also shown how the process of temporary architecture is essentially no different to that of a permanent project. For these architects and designers, temporary projects involve the same design processes, the same ideas about architecture and the city, the same aesthetic concerns, the same social and political issues, just in a more condensed form. ‘If you let go of the exclusive emphasis on structure and think about what was produced as a way of working, a set of relationships, a demonstration of possibility, the temporariness starts to look more background,’ notes Assemble. Yet, temporary architecture has much to teach permanent architecture about breaking the rules slightly, thinking outside the box and making our built environment accessible, open, intuitive, unrestrictive and that little bit playful. These should be standards for every project. Much of the work here is inherently democratic, with communities and volunteers invited to take part in their conception and thus reconnecting us to the process by which our urban spaces are made. With temporary architecture, as EXYZT says, ‘everybody can be the architects of our world’.