Introduction /

CATE ST HILL

Temporary architecture has been getting a bit of stick in recent years. It’s often been misrepresented as a flimsy trend, fuelled by a frenzy of meanwhile projects following downturns in construction inactivity and developers cashing in to avoid longer-term problems and difficult questions. It’s been seen as a photo-ready quick fix: easy, entertaining, and often, mistakenly, cheap – a marketing ploy to attract investment in an area and show the world it’s ‘hip’. It is now synonymous with shipping containers, street food and music festivals, and that advertising buzzword ‘pop-up’. But there is a long history, continuing today, of a more holistic temporary architecture that deals with fundamental questions of how we might live, work and play more harmoniously together. These structures, situations and events quickly appear and disappear but they are designed to invest and embed themselves in a community, public space or set of ideas. They open up possibilities, test scenarios and subvert preconceptions of what our cities should be like and how we should behave in them. Their architects and designers, often young, are pushing the boundaries of architecture and taking the city back into their own hands.

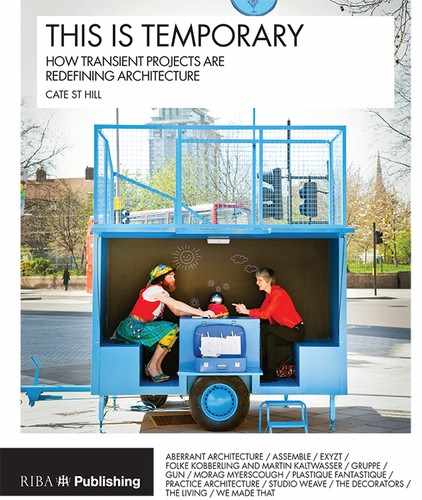

So, what can we define as temporary architecture? And is it anything new? Temporary architecture in the context of this book can be labelled as purposely short-lived structures, exhibitions and programmes that create experimental sites for interaction and engagement, ranging from a tiny travelling theatre and floating cinema to a community lido on an abandoned railway site and a theatre made entirely from scrap material. Sometimes they are designed for specific biennales, festivals and commissions, but they can also be self-initiated, do-it-yourself building and grass-roots platforms for collective, participatory design. Usually they’re experimental and innovative, questioning the form of permanent architecture gone before. Always they’re for public use and involve the public as key protagonists in their formation and performance.

If we take temporary architecture to be something that is not permanent, then it has been around, in one form or another, since time immemorial, from prehistoric wooden huts and shelters, through medieval stage sets, circuses and world fairs, to the mobile home and post-war prefabs, and wartime and disaster relief. In contemporary architecture we are more familiar with temporary exhibitions and pavilions: Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s L’Esprit Nouveau Pavilion (1925), Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion (1929), Alison and Peter Smithson’s House of the Future for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition in London (1956) and Charles and Ray Eames’ IBM Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair (1964-65) – prototypes for modern living that showed their creators’ provocative ideas on the future of architecture and urbanism. They were also about transforming architectural forms into compelling, memorable visual images – a form of advertisement. Archigram also challenged conventional approaches with mobile, inflatable or temporary components, pods and capsules in the 1960s and 1970s, with projects that embraced the digital information revolution including Walking City, Plug-in City and Instant City (although these remained unbuilt). The Smithsons, however, saw temporary architecture as following in the tradition of the centuries-old theatrical structures that defined tastes and trends:1

These concepts and ideas about rethinking society, seen in these pavilions, are similar in many ways to the temporary structures featured in this book – building ‘alternative possible worlds’, not entirely real, not entirely fictional, as The Decorators’ Mariana Pestana notes in her essay on page 141. Yet the architecture here is also somehow different: they’re not prescribing or dictating specific ways to live in the future; nor are they prototypes to be repeated on a grander scale. Instead, each is a unique (and sometimes bizarre), rule-breaking structure, a vehicle for playing with thoughts and ideas – and it is these thoughts and ideas, and often not the physical thing itself, that could have an impact on the future of architecture. It’s also more about the process of building and the political nature of architecture, as we shall find out.

This book features 13 interviews with 13 architects and designers, ranging widely from the more traditional small architecture practices and studios to multidisciplinary collectives and cross-discipline designers, spread across the world from New York and Santiago to London, Berlin and Zürich. All have started their own firms and continue to work on their own terms. Each has, in his or her own way, inspired new definitions of architecture, not just in terms of their physical outcomes, but also in the way that they go about creating them – and that’s why they’ve been singled out here. I have tried to avoid some better-known, medium-sized practices that also do temporary architecture, mainly because I wanted to include smaller, younger architects and designers that are collectively ‘emerging’ as a sort of new generation of subversive, socially minded practices.

What they all have in common, apart from being relatively young in architectural terms and infectiously passionate about their craft, is a concern for engaging people and enriching local communities, and for collaborative, participatory ways of designing, making and building. These architects aren’t daydreamers: they’re making extraordinary things happen. The projects here are inventive, experimental and playful, but at the same time they’re also well-considered and empowering ways to create animated, deeply rooted places in the neglected, disused and sometimes inaccessible parts of our cities. The book is divided into six themes or features: Young architects’ programmes; Public realm and engagement; Playful storytellers; Collectives and self-initiated projects; Participative building and materiality; and The art world and temporary architecture. It is organised so that each chapter represents two or three practices that exemplify one of these features. Many of the practices’ work crosses over these themes and the placing of a particular practice within one chapter rather than another is purely for the purposes of drawing out similarities and connections between groups, and organising the content into a cohesive whole.

These 13 architects are just a fraction of the whole picture; they are not meant to comprise an exhaustive list but to illustrate the temporary architecture phenomenon today. They are largely confined to urban areas, most predominately big cities such as London, Paris, Berlin and New York, but that is not to say that temporary architecture is not happening in more peripheral situations or rural locations. If a study were to be done of all the little temporary installations, events and exhibitions taking place across the world, by architects and laymen alike, the list could go on indefinitely. This book is simply a succinct representation of the temporary situation in this moment in time.

The first chapter deals with young architects’ programmes, namely the MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program, an inspiring annual competition open to emerging architects and students that requires them to design a temporary structure for the summer on a site in Long Island City, New York. It has since expanded to similar initiatives across the world in Rome, Santiago, Istanbul and Seoul. The programme allows young architects the freedom and support to test out ideas, experiment with innovative structural approaches and materials, and put their previously unrealised methods into practice. This chapter aims to show how programmes like these are creating unique opportunities for small, young practices with limited previous built experience, such as New York-based The Living and Chilean-German practice GUN Architects, and how they can be formative to those practices developing their own manifesto.

Chapter 2 looks at architecture practices that are creating public realm projects, urban studies and area strategies in order to develop a deeper understanding of an urban area and to engage local communities in long-term change. This chapter includes London-based We Made That and multidisciplinary team The Decorators (made up of an architect, an interior designer, a psychologist and a landscape architect). Both practices have developed creative, tailor-made programmes for neglected, run-down high streets and sites across London, from Poplar’s Chrisp Street Market to Croydon’s restaurant district. Initiatives include a radio station for broadcasting debates, an online town team to help crowd-source ideas and a toolkit to help communities create their own temporary and meanwhile projects in empty shops and vacant land. This chapter aims to show how temporary architecture isn’t purely concerned with temporary structures, but can comprise a whole host of initiatives – a complicated sum of vibrant parts. Similarly, but perhaps a bit more playfully, the third chapter focuses on imaginative, young practices creating temporary structures backed up by rigorous research into the history of a place and the construction of whimsical narratives. Profiled are Studio Weave and Aberrant Architecture, who both share deep social aspirations to connect these physical structures with people and place.

The fourth theme centres on multidisciplinary collectives who are pioneering a self-initiated style of building that engages local communities in the making process, and relies on collaborative, hands-on teamwork. Here, we meet French collective EXYZT, a motley team of architects, artists, graphic designers and photographers that completely inhabit a project for the few weeks or months that it is around, as well as London-based Assemble and Practice Architecture, who were both influenced by working with EXYZT on Southwark Lido in 2008. All three groups are redefining the scope of conventional architectural education and practice, showing how post-recession young architects can forge their own path and have a profound impact on our cities. Taking this idea further, Chapter 5 looks at two Berlin-based teams also challenging preceding traditions: artist-duo Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser, and Plastique Fantastique. Both use materials to gather and empower people to think about sustainable, self-initiated acts of building.

The final chapter deals with the blurring lines between disciplines, namely the art world and the architecture world, in the creation of temporary architecture. Case studies here include Zürich-based GRUPPE and London-based Morag Myerscough, who trained in graphic design but has since gone on to collaborate with architects and developers on temporary pavilions, installations and wayfinding projects. This chapter aims to illustrate how temporary architecture can slip between disciplines, none superior to any other. Instead, it’s about opening up creative possibilities, expanding design processes and embracing collaboration – architecture as a cultural movement.

All the chapters attempt to depict alternative modes of practising architecture that go slightly against the norm and challenge the conventional role of the architect. In this book, I hope to show that although only around for a short amount of time, these temporary projects can, for an intense moment, provide shared, valuable experiences in urban public spaces. They are not just about appearance, but about the evolution of ideas and processes. Finally, I hope to show that temporary architecture is more than just a trend – rather, it is a sustainable model of building for the future.