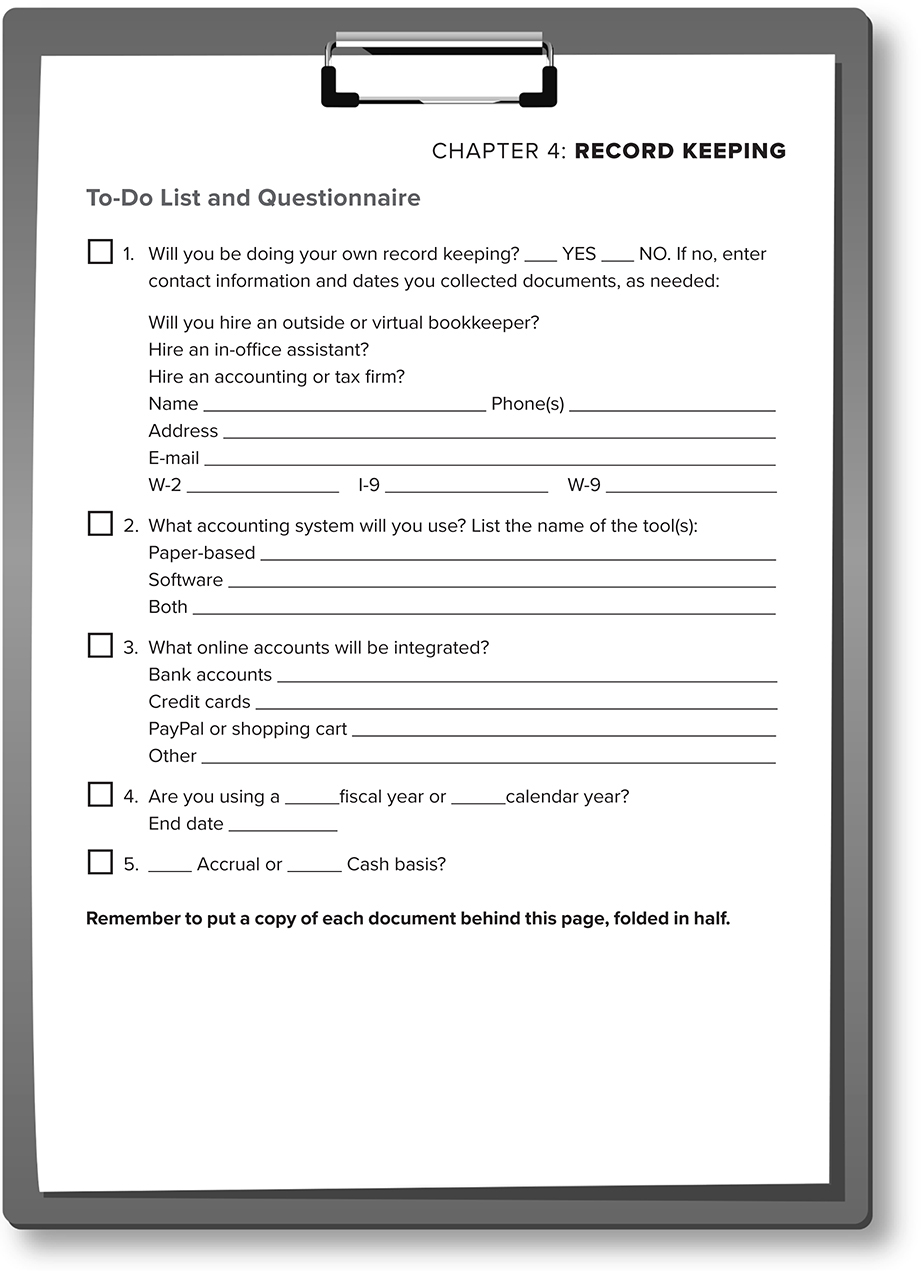

4

RECORD KEEPING

Delegate your record keeping. But more importantly, make sure the person you are delegating to has impeccable ethics and independent oversight by a quarterly accounting audit.

—ADRYENN ASHLEY OF WOWISME.COM

You’ve probably never thought about it this way, but record keeping is a language. In fact, it’s a series of different languages, depending on who will be using or reading your records. In Chapter 3, you made the big decision. You picked out the body your business will be wearing—even if it’s just for the short term. Now, it’s time for you to learn to communicate properly for the body you’ve chosen.

While the languages are different, they have the same roots. Just as French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian all come from Latin (Romance languages—because of the Roman roots), English also has a strong Latin influence. If you listen closely to those other languages, you’ll find you can understand them a little because you speak English.

It’s the same thing with your records. The basics are the same across the board. The words used to describe concepts and transactions are the same, but the nuances and details are different the higher up the food chain your business gets. Refer to the glossary later in this chapter to demystify the terminology that tax professionals and accountants use.

Keeping Records Is a Pain!

Many small business owners are so busy trying to run their businesses, hold it all together, and keep the bills paid that there just isn’t time for bookkeeping, too. Besides, who knows how to do it correctly? If you can’t do it correctly, it can be daunting, can’t it?

But you have to do it. Really, really, you do. If you don’t keep decent records, how can you possibly know how your business is doing?

Some people operate on the principle that if there is money in the bank account, everything is fine. One set of business owners I knew used to call up the bank in the morning to find out their balance. (Today, of course, you can look it up online.) If there was money in the account, they wrote checks. They didn’t take into account the fact that the checks they wrote yesterday had not cleared yet. As you can imagine, they were bouncing checks all over town without understanding why. Their employees understood. The minute they got paid, they ran to the bank to cash their paychecks before any of the owners’ wild checks hit the bank.

Making It Painless

Adryenn Ashley has some tips for you. Adryenn is an award-winning author, filmmaker, and speaker, and the founder of Wow! Is Me (http://wowisme.net).

When you’re just starting out, you do your own “expense reports” to give to the bookkeeper. OK, when you’re really starting out, you hand over a shoebox full of receipts with a slightly apologetic look on your face and say, “Can you make sense of this?” Once you have a system in place, then it’s up to you to mark your receipts. Well let me tell you, when you get to a certain earning level, it is actually more practical to have a savvy bookkeeper do it all, import the data from the bank (so that means limiting cash spending and using debit cards for easy tracking), match up the data to appointments in the calendar, and only spend 10 minutes asking you to identify the dozen or so transactions from the month that she can’t figure out. Your time spent on bookkeeping per month? Ten minutes. It all boils down to having a bookkeeper who is a self-starter and understands your habits.

But don’t forget quarterly audits, not done by the bookkeeper, but by a third party. I once discovered my bookkeeper had been writing herself checks (using my signature stamp) for her pay. Rather than putting herself on payroll, she had been deducting herself as office supplies so she wouldn’t get a 1099 at the end of the year! Tsk-tsk! I would never have found that without the audit. So, yes, delegate, but more important, make sure the person you are delegating to has impeccable ethics and independent oversight by a quarterly accounting audit.

I use QuickBooks Accountants edition because I have multiple entities in different segments! I have the bookkeeper come in, and the auditor comes in quarterly on the sly. I don’t want people to behave because they know they’re being watched; I want them to do an honest job because they’re honest people! I love, love, love my bookkeeper now! She’s amazing. She used to work for a bank doing very complex stuff, and so I’m a walk in the park for her.

I hired a more expensive bookkeeper who is a QuickBooks guru to make sure that it was properly done. You can also have your CPA’s office do it. It’s just more expensive. For me, having things in the right category was the most important. I did a full 10-year audit of a company (I was a forensic accountant for the movies for a while), and it was amazing what I found . . . designer sunglasses written off as utilities . . . once you get a feel for how the company runs and what’s normal, the abnormal stands out.

Types of Accounting Systems

It’s very important for you to track your incoming funds and your expenditures if you want to have success as a small business. The simplest of accounting systems is just a summary of your various sources of income and a list of your expenses. Since that’s essentially a list of numbers, there’s no real way to tell if anything’s missing. That’s called a single-entry system. Whether you maintain these records manually or on a computer—using something like Quicken—you have no cross-reference to ensure your books are in balance.

Here’s an example of a single-entry system’s transactions. In August, John fixed his car for $250. He paid his printer $150. John picked up office supplies for $75. His rent was $550. He bought a copy machine for $775 using his credit card. John’s expense records might look like this:

As you can see, there’s nothing to show you how much money came from his bank account, cash in his pocket, or from increasing the balance due on his credit card. There’s nothing to tell you that the copy machine is an asset rather than an expense.

There’s no balancing factor in single-entry systems. Being in balance is an obsession for accountants and bookkeepers. It tells us that all the pieces of the puzzle are there. That’s why businesses generally use a double-entry accounting system. Both sides of each transaction are recorded, and when the numbers don’t balance—we know something’s missing or something’s entered incorrectly. In a double-entry system, John’s transactions for August would look like this (with some more detailed descriptions, of course):

Using a double-entry system, you always come out to zero, because assets = liabilities + capital.

Not everyone will need a double-entry bookkeeping system. Corporations will. Very small businesses can get by with the most casual of records. Although if you start out with a balanced bookkeeping system, even for a tiny business, you’ll already have your system in place when growth is better than you expect. You can save the cost of converting or entering a year’s worth of data—or data for several years.

While paper-based bookkeeping systems are perfectly adequate, I recommend that you don’t use them. If you’re starting a business in this millennium, do your accounting on a computer. It’s much easier and faster to correct posting errors. Reports are at your fingertips whenever a banker, your tax professional, or anyone else asks. The software will give you enough information to prepare budgets or to catch fluctuations in costs or income.

One of the things I love about today’s computerized accounting systems is that you no longer have to sort checks into numerical order or invoices into date order before you enter them. You just enter everything in any order you find it—and the computer puts each transaction into the right order. When working with people who haven’t done bookkeeping for years, this is especially helpful. As I come across checks or invoices from other years, I can enter them into QuickBooks as I go along. I just need to remember to set the paper aside and file it in the box or drawer for the right year. You’ll find that feature very helpful if you have receipts in your car or your kitchen or with your children, your boss, or your staff. You know how you often get receipts and documents from your team in a piecemeal fashion? With a system that operates like QuickBooks, you don’t need to stress about reorganizing the entries to get them to appear in the right month when you get yet one more document they forgot to tell you about.

Another advantage to the computerized system is that it will give you reports for any time period. If you need to get a profit and loss statement for January through May in order to compute your estimated tax payment, it takes seconds with a good software program.

One feature that some of the accounting software companies are offering these days is online accounting. You pay a monthly fee, and they keep the software updated. You can access your accounts from practically anywhere on this planet. You and your tax professionals don’t need to exchange files. You can go online together and discuss the accounting and make revisions or corrections any time you like. The only drawback is that when you use an online accounting system, you can only use it for one company. You must pay separately for each company you operate. When you buy bookkeeping software, on the other hand, you can generally use it for as many companies as you like.

Do yourself a favor and get the computer and the accounting software or use an online system—whatever works for you. Just be sure to automate your accounting.

Doing It by Hand

If, on the other hand, you really prefer to do your bookkeeping by hand, take a look at Tables 4.1 and 4.2, which show how to set up a multicolumn spreadsheet. (If you want to do this on paper, you can buy 13-column spreadsheets.) As you can see in both tables, all the numbers to the right of the totals must be added together to equal the total in Column D, the “Total Check” column.

TABLE 4.1 Company Do-Re-Mi Cash Receipts Journal, November 2016

TABLE 4.2 Company Do-Re-Mi Cash Disbursements Journal, November 2016

If you’re going to do your bookkeeping by hand, be sure to total each page separately. Then have a total page for the month for both cash receipts and cash disbursements reports. Once the month is balanced, total all 12 months to get the whole year.

Use the “Other” column (see Table 4.2) for expenses that are not necessarily recurring. At the end of the month, subtotal each item in the “Other” column. Add those sums together for the year.

Hand over all these pages to your tax professionals, who can review them and use the information to complete your business taxes.

The IRS Says It All

If you prefer not to take a full-blown bookkeeping course, start out by reading (or skimming) two IRS publications. The first one is IRS Publication 583, Starting a Business and Keeping Records (available at https://www.irs.gov/publications/p583/), and the second is IRS Publication 334, Tax Guide for Small Business (available at https://www.irs.gov/publications/p334/). Keep a highlighter pen and a pad of small Post-its handy to mark the passages that apply to you.

Fiscal Year

In general, you will set up your bookkeeping system using a calendar year for most entities. Sole proprietors may only use calendar-year bookkeeping systems. Partnerships and pass-through entities may use the year of the majority owner. If that owner is a person, it will be a calendar year. When corporations or other partnerships own the majority interest, the partnership may use the fiscal year of the owners.

Corporations may select any year that suits them. Once the year is established, however, you may only change it with written approval from the IRS.

Accounting Styles

You have a choice of using either cash or accrual accounting—right? Nope, there’s also the hybrid method and percentage of completion.

The cash method of accounting is the simplest and the most confusing. As with all things tax, there’s always a dichotomy. It’s the easiest method for people to use because you only report income from money you’ve actually received. You only report expenses for bills you’ve paid.

If it’s that simple, why is it confusing? Perhaps it has something to do with the definitions of what is considered “received” and what is considered “paid,” and the exceptions to the rule. Chapter 5 will explain “constructive receipt”—or define when money is considered received. Chapter 6 will explain when the money is considered spent—and the few exceptions that crop up.

A key area of confusion for people who have not studied accounting (in other words, most of the business population) is why they can’t write off bad debts—bills clients or customers never pay.

That’s because you must be on an accrual basis to use bad debt write-offs. Even then, it’s not as useful as you might think. You see, when using an accrual basis, you’re reporting income when you send out the invoice to the client. So you’re paying tax on income you haven’t received—or may never receive. That’s why you may write off bad debts when you can’t collect the money. You’ve already included that debt in income.

Why would anyone want to use accrual accounting (aside from the times it’s required by law)? Because you also get to deduct your bills before you pay them. Some companies have customers who compensate them quickly, so their accounts receivable (money from clients) is low. But they have 60-day or 90-day terms on their accounts payable (bills they pay), so they have large unpaid balances due—that they get to deduct at the end of the year. In other words, when you can deduct a lot of money that you haven’t spent yet but only need to pick up a small amount of income, the accrual system is ideal for you. Unfortunately, most small businesses are not in that position. Worse, if we do get enough credit so we don’t have to pay bills for 90 days or so, it can get us into deep debt. So please be careful.

When is this kind of accounts payable time frame important to your business—and when does it make sense? In two primary instances. When your income comes from government contracts—or you sell large volumes of products to major national retailers like Sears, Walmart, and Macy’s. When you contract with them, you generally have to spend a fortune to produce, package, and deliver your product—but won’t get paid for 90 to 120 days and they feel free to return discards and damaged goods (that they were careless with). In fact, one client who finally got his products into Sears told me that he had to buy up his competitor’s entire inventory (about $1.2 million) before Sears would make room for his merchandise. So even when your contract appears to show a big profit, you need a lot of credit or a lot of cash to carry those accounts receivable—and the other onerous terms of the contract. (Of course, if you know what you’re doing, you could avoid this long delay in getting your money by learning how to get your sales factored . . . now that’s a whole other interesting story! Perhaps for another book.) Remember, we told you to explore factoring in Chapter 1 when we talked about the schmatte business?

Typically, businesses such as medical practices, which have large unpaid accounts receivable balances, should always be on a cash basis. There are always more and more invoices that patients are refusing to pay or paying slowly. And, with Medicare and insurance companies setting limits on fees for various procedures, the medical practices don’t actually ever receive all the fees they bill. By using the cash basis of accounting on its tax returns, a medical practice never has to report all the income it never received.

Let’s pause for a second here. Please understand that my goal is to explain how to handle accounting for tax issues. But, for day-to-day business issues, smart businesses should use an accrual accounting system for their operations. Yes, you may use accrual for operations and the cash basis for tax reporting. That’s not cheating, and it’s not dishonest. It’s perfectly permissible. Just make sure when you pull reports for taxes that they are cash basis—and that the balance sheet and profit and loss statement were printed the same day. (The reports will show the printed date.)

The accrual system means that you enter all the fees, sales, and charges constituting the business’s income—even if you haven’t been paid. You enter all the bills that need to be paid—even if they just arrived and you don’t have to pay them for 20 or 30 days. By putting all these numbers into the system, you can get a variety of important reports.

1. Budgets. Knowing how much your overhead is each month helps you understand how much income you need to generate to cover expenses and give you money to live on and play with.

2. Accounts receivable aging reports. So you know when to send invoices and to whom—and when to send stronger notices or . . . sue.

3. Accounts payable aging reports. So you know how much money you need to have to pay all your bills; or to see which bills are still eligible for the special discounts you can get if you pay quickly.

4. Profit and loss comparison reports. Compare income and expenses by month, quarter, year, and so on. You can see if income has gone down, expenses have gone up; seeing significant changes and patterns can alert you to trouble before it’s too late to fix the problems; you can see if you’re not charging enough for your products and services to cover your costs.

Larger corporations tend to use the accrual method. This lets them enter all their purchase orders, purchases, and shipping manifests or bills of lading into accounts payable in their accounting system. Doing this makes it easier to match up purchase orders with what was actually delivered. The company then has the invoice in its cash management system and can do a better job of tracking when to pay the bill. Companies on the accrual system also enter all the invoices for their sales into the system. That way, if a customer pays off only part of an invoice, the computer can keep track of the amount of money the customer still owes.

If you use the accrual method and know how much cash you have, how much you expect to come in, and how much you have to spend, it becomes much easier to take advantage of vendors’ discounts. (Do they still give you a 2 percent discount if you pay within 10 days?)

The hybrid method allows a business to use the accrual method for its stock and inventory, but the cash method for everything else.

Percentage of completion is generally used for large projects, like construction and engineering. You report your income and expenses based on the percentage of the project that has been completed. So if 15 percent of the bridge has been built, you’ll report only 15 percent of the contractual income—even if you’ve received 30 percent of the payment. And since you often must buy half the materials in advance, you’ll still only deduct 15 percent. The rest will be inventory.

Records You Must Keep

In our office, we keep everything. Our office and our storage area are overflowing with paper. Why? I don’t trust magnetic media to be readable when I need it. It’s happened in the past, when something we meticulously backed up was corrupted by time or heat or . . . never got backed up properly to begin with. Besides, how many times have you changed your backup devices? You’ve used discs, then ZIP drives, then tapes, then CDs, DVDs, and now—thumb drives. Do you still have a 5¼-inch “floppy” drive to read those old discs? Heck, my tiny thumb drive has more storage on it than they used for the entire space program in the 1960s.1

These days, the technology is better, easier, and faster when it comes to scanning. If you’re smart, you’ll get a scanner with a feeder so that you don’t have to scan each page by hand—or use your smartphone. When you store the images electronically, make sure you get the front and the back, as appropriate. The best format to use for long-term access is Adobe’s PDF file format. Adobe seems to be smart enough to keep its technology backward-compatible. In other words, you can still read a PDF file from 2005 even though the PDF technology has advanced dramatically since then.

What Kind of Documents Should You Keep?

• Most important, make copies of all checks. When customers pay you, copy their checks. Then copy their checks again, this time with your deposit slip. Put the copies of the checks in your customer files, with their invoices. Put the deposit slip into your banking file. Later, when you reconcile your bank account, if you’ve overlooked an entry, you can find the details quickly. (Shhh . . . don’t tell anyone, but this practice also makes it easy to find your clients’ bank accounts if they stiff you and you have to get a court judgment.)

Consider making two copies of the invoices you send to clients, one to go in the client’s file and the other to go into a master invoice file. All the invoices in the master file should be in numerical or date order. If you use numbers on your invoices, make sure you have each one, even if it’s voided. The IRS looks for gaps in numbering sequence. To them, that means you invoiced someone and pocketed the cash off the books. To you, it probably meant your printer ate it or you messed up and prepared a new one. Just reprint it, mark it “void,” and add it to the stack.

Making copies will also help you during an audit if the check you’re depositing happens to be a loan from you or a cash advance. It will be easy to prove to an auditor that this was not income.

• Next, save the canceled checks as a record of your spending. You don’t need to copy them; just be sure to keep them safe and dry. You need them to prove you paid a bill when a vendor says it never received your check. You’ll also need canceled checks for tax agencies. And you’ll need the information for audits. Naturally, these days, we are not getting them from the bank at all. Instead, they provide the copies of the canceled checks in their online database. Get into the habit of downloading those statements and canceled check copies every three to six months. The bank will keep the database open to you for about a year or two. But, if you really need the copies for an audit or lawsuit, you will need something from the closed year, and would have to pay for it. Protect yourself from that problem by establishing smart habits.

• It’s very important to save paid bills. Some people chill my soul: when they pay a bill, they throw it out. Nooooooo! The IRS wants to see what you’re paying, not just how much. Do you like doing this with credit card bills? Please stop. Save all your paid invoices and your credit card statements. You’re buying a lot of things online or electronically these days. Set up a filing system for all those electronic records. The nice thing about being able to save these records is that you can put them into multiple places, in seconds, such as folders for master purchases, all your transactions with that company, and the category of expenditure (software, gasoline, training, etc.).

• Save bank statements. Keep them all—from all accounts.

• Save receipts. Save receipts when you’ve been out of the office shopping. Bring back all the receipts for the money you took from petty cash and for the things you charged on your credit cards. You’ll be able to match up the invoices with the statements. If there are errors, you’ll catch them and get your refunds. Sometimes, the computer system produces posting errors, or it gets hacked. With the receipt in hand, you have proof of the correct charge.

• Keep copies of purchase contracts on all assets. When you buy a car, a copy machine, a computer, or whatever, keep copies of all purchase contracts in a master file. You’ll need copies of those invoices to support your depreciation expenses. Even though the IRS can, technically, only go back and audit you for three years, if there is something on a tax return that was bought six years ago, the IRS has a right to request the original documentation. For instance, you bought an editing machine for $30,000 in 2010. You didn’t need the deduction the first year, so you depreciated it over seven years. Your last year will be in 2017. An auditor comes along to audit in 2015. He or she may audit 2012, but the year 2011 is not permitted. However, you bought this editing machine in 2010, and it’s still generating a deduction. The auditor may ask to see the purchase document, even though you bought it five years before the audit. The auditor is not being unreasonable. After all, you’re still taking a deduction for it. Save time—just have it handy.

• Keep information about loans. Keep a copy of the full loan contract, with all the details on the payoff terms. To verify the interest deduction, the IRS will want to see the contract so it can do its own calculations. Having a copy will also be a big help to you in case the interest charges are in error. I have seen banks and finance companies make errors all too often. You can prove the correct interest using your paperwork and your own loan amortization schedule. Use Bankrate.com’s loan calculators and print out the report. It’s available online at http://www.bankrate.com/calculators/mortgages/loan-calculator.aspx.

• Retailers, keep cash register receipts. Always make sure that you match the information on your cash register receipts with the entries in your accounting system. If your cash register software is properly programmed, it should give you separate totals for cash and for credit card payments by customers. Match that up with your accounting entries. If the cash is short because you kept some of it to use for purchases and errands, record the total income received. Then deduct the amount you kept as a charge to petty cash on hand. Be sure to bring back the receipts. For some reason, I find that with retail establishments, somehow the income on the books rarely seems to match the tape. We spend a great deal of time tracking down inconsistencies. Please make sure your tax professional helps you reconcile any differences.

• 1099-Ks. These come from your merchant credit card companies, PayPal, and other services that you use to collect money from customers or clients. I am hearing from tax professionals that there are often significant discrepancies between the total sales reported on those 1099-Ks and the total sales on businesses’ books. One of the problems is that the 1099-Ks report the income (only) from every transaction. They don’t take into account the refunds or chargebacks, or other reductions of those sales. It’s important for you to reconcile your income to those reports, and not just for tax purposes. But if there are large discrepancies, there might be some serious problems—like employee theft, identity theft (someone using your account to run charges through), or . . . who knows?

• Save tax returns of all kinds. You file paperwork with your city, county, state, and federal governments. Keep copies of each item in its own file in date order with the most recent on top. Add up all your sales tax returns to make sure you’ve reported the same income on your income tax return as you did on your sales tax return. The IRS is on a payroll audit kick. Be sure to keep all your payroll records, time cards, and paychecks or proof of electronic payments. Also, keep copies of all the expense reports and reimbursements—to prove those payments were not payroll.

• Documentation of electronic transactions. As I’ve pointed out, many of your transactions are happening electronically now. I keep hearing lame excuses from people saying they don’t have receipts or records because they paid (or sold) electronically. Don’t BS me or your tax professional. We live in this world, too. And we see the flood of e-mails that come in after each purchase—and the e-mail confirmations that come in after each sale. Get organized and set filters to file these records. If you don’t know how, invest in a techie to set up systems for you. It’s not rocket science . . . well, not yet.

How Long Should You Keep Records?

Keep all tax returns forever. Ignore what anyone else tells you. There have been too many times that the IRS or the state has made demands on tax returns filed 8 or 10 years ago, saying they were never filed. If you have a copy, you can insist it was filed.

If you send money in with those tax returns, keep a copy of the canceled check in the file with the returns. If you got a refund, make a copy of that, too. If the IRS grabbed your refund, you won’t have any check copies, but you’ll have a letter saying it grabbed the refund from a given year. One of these three items will prove that your return was filed. These days a lot of these transactions are happening electronically. Keep a copy of the electronic receipt when you pay online. If the transaction goes directly in or out of your bank account via the IRS’s direct deposit or Direct Pay system, keep a copy of the relevant bank statement with your tax file.

Keep copies of all asset purchases for the life of the asset plus 10 years or for the life of the loan on the asset plus 10 years. If it’s real estate, keep the paperwork until you sell it, plus 10 years.

Basically, keep everything for at least 10 years after its useful life or tax return filing date is past.

You realize, of course, there is this rule in the universe: as long as you keep it, you won’t need it. The minute you throw it out, everyone will need it.

Until two years ago, I kept all my client records from way back in the 1970s. Finally, I got bold and decided to give the records to the clients whose addresses I still had—and to shred the files of people I couldn’t reach. I only shredded files that were at least five years old, plus my own personal records.

One hour after I finished shredding, a client who’d filed bankruptcy a couple of years earlier, owing me money, called. He wanted the paperwork on the money he owed me so he could pay it off. (He had never listed my debt in the bankruptcy.) Well, I didn’t have the papers, so I couldn’t prove what he owed me. If it had been anyone else, I could have waved goodbye to that money. Luckily with Adam, he just shrugged and sent me what he thought he owed me.

Glossary of Bookkeeping Terms

Above the line. Accounting industry jargon for expenses that are deducted on the first page of Form 1040. These expenses are generally deductible as adjustments to income. They reduce your adjusted gross income, which allows you to increase medical expenses and miscellaneous itemized deductions. (Also see Below the line.)

Accounts payable (or A/P). Invoices you’ve received, or are expecting, for things you have purchased or things you have had delivered to your place of business or to your clients. For record-keeping purposes, only accrual basis companies report A/P on their financial statements.

Accounts receivable (or A/R). Money owed to you by your customers or clients after you have sent them an invoice. A/R does not include loans that are being repaid to your business or anything else. It is just income due to you, in whatever form, as a result of a business transaction.

Accrual. An accounting method that includes all your company’s sales and purchases, even if you haven’t collected the money from clients or paid your vendors. Most people in business alone are wise to avoid this method. It involves an assortment of complexities and rules. (See Cash basis.) Accrual accounting is good when your outstanding business debt is high, but your accounts receivable are low.

Adjusted basis. The tax cost of your asset, with improvements added in and things such as depreciation and casualty losses deducted. This is the tax cost after all adjustments mandated by the tax code have been applied to the cost. (See Basis.)

Adjusted gross income (AGI). The last number on the first page of your Form 1040. The lower this number is, the more apt you are to be able to deduct IRAs, take advantage of various credits and losses, and use medical expenses and miscellaneous itemized deductions. Several other numbers use this as a starting point. Please get familiar with AGI.

Advances. Loans, often to employees or owners, that will be repaid from their next payroll check or from their draws. They could also be funds given to workers before they go on a trip or to a business event. In that case, the workers must submit an expense report with receipts or mileage data adding up to the amount of money advanced. If they have money left over, they must either return it or have it deducted from their compensation. They may opt to have it added to their compensation and taxed, instead.

AGI. See Adjusted gross income.

Amortization. Derived from the Latin word for “death,” the value of certain designated assets prorated over a period of time. You deduct a portion of it each year, much like depreciation.

Assets. Things the business owns that aren’t part of the product being sold. Assets include bank accounts, investment accounts, inventory, vehicles, loans to people, equipment. They also include intangibles such as patents, copyrights, client lists, and goodwill. Businesses on accrual will also report their accounts receivable under assets. Assets are the first section of the balance sheet.

Audit trail. The details of all the transactions behind a number on the financial statements, including all adjustments. Most consumer accounting or bookkeeping software has good audit-trail features. It lets you run reports and then click on the number to get the details within that account. However, it also lets you correct the entry directly. Once you do that, there is no evidence of the error. Professional accounting software requires you to make a journal entry to correct each error, leaving a history of entries.

Balance sheet (BS). A report that shows the following relationship of your finances: assets = liabilities + capital (or equity). The balance sheet does not include your expenses or income—just the profit resulting from them. The “income” line on the balance sheet must equal the net income line on the profit and loss statement. All prior year’s profits are rolled over into retained earnings.

Basis. Tax cost of an asset. It generally consists of the purchase price. For some assets, the basis is the fair market value (FMV). To keep things interesting, when it comes to depreciating business assets, the basis is the lower of cost or FMV. But for estates, it’s often the higher of cost or FMV. (See Adjusted basis, Fair market value.)

Below the line. Accounting industry jargon for itemized deductions. These are expenses deducted on Schedule A. They don’t reduce your adjusted gross income.

Capital (also called owner’s equity). Capital represents investments in the company. Depending on the type of company, it might include stocks (corporations), shares (LLCs, LLPs, partnerships), or simply owner’s equity. The capital section of the balance sheet includes the money invested in the business, the draws taken from the business, and the profits or losses of the business. It also includes any money spent to buy back company shares or stock from owners or partners.

Cash basis. The most common method of accounting. As income, you only include the money for which you have constructive receipt. (See Constructive receipt.) Under expenses, you include only the bills you’ve paid. Certain things that look like accruals also get picked up—payroll and sales taxes to be paid in January (or at the end of your quarter). Credit card purchases are included in cash basis reporting, even though you have not paid for the purchases. They are treated like loans you’ve taken out at the time you made the purchase.

Check register. That little booklet the bank sent you with your checks. You’re supposed to list all the checks you write and the deposits you make. Add your deposits and deduct your checks and bank fees. Et voilà! You know how much money is in your bank account, at a glance.

Closing the books. When a company finishes the accounting for a month, quarter, or year, and reconciles all the accounts, it closes the books for that period of time. No more entries are made into those ledger or journal pages. If errors are found later, they must be corrected using a journal entry. You can’t just go back and erase the wrong entry. You must either debit or credit the error to get it right. That’s in formal accounting systems. Today’s software doesn’t require that you close the books. It lets you make corrections later, if that’s when you reconcile your bank statements or decide to enter your transactions.

Constructive receipt. Money you’ve received at a specific time, with the right to use it. (See Cash basis.) Usually this is important at year-end. A check was mailed to you by your customer in December, but you received it on January 2. Did you have constructive receipt of that check in December or January? Here are some common examples:

• If someone gives you a postdated check, you don’t have the right to deposit that check until the date.

• On the other hand, let’s say you own a controlling interest in another business. That business owes your company $5,000, but you tell the business to hold on to your money until next year. The IRS considers this as if you have constructive receipt of that money. You’re the one who is in control of when that check is issued.

• A third case is where someone owes you money. You tell the person to pay that money to a third party to whom you owe money. Even though that check never hit your books, the IRS treats that as if you had constructive receipt of the money. You controlled how that money was spent.

Credit. In accounting, a credit is the negative half of an accounting entry (debits and credits). It reduces the balance of the account it’s posted to. On the asset section of a balance sheet, it reduces the asset. A credit to the bottom of the balance sheet increases liabilities or equity. On the profit and loss statement (P&L), a credit increases income and decreases expenses. A credit balance on the P&L means you have a profit. (See Debit.)

Debit. The reverse of a credit. (See Credit.) A debit balance on the P&L means you have a loss—you’re in the red. When you debit your bank account on your books, it means you’ve made a deposit. When the bank debits your bank account on its books, it means you have drawn money from it. Debits and credits are a confusing concept if you can’t visualize both sides of the transaction.

Depreciation. The act of writing off the cost of an asset over a specific period of time, as designated by the tax code. Chapter 6 expands on this issue.

Double-entry bookkeeping. A balanced system in which each transaction has two sides; e.g., when you write a check for office supplies, you reduce the balance in your checking account and increase the balance in an account called office expenses.

Draws. In partnerships or pass-through entities, funds paid to partners or members. They are considered advances against income. This is not income. Draws are reported on the books as a negative amount under capital. At the end of the business year, they are netted against retained earnings—or the owner’s capital account. (See Capital.)

Expense report. A worksheet submitted by employees wanting reimbursements for out-of-pocket expenses. It may also be an accounting for monies advanced before a business trip or shopping trip was made. Generally, receipts are attached to substantiate the expenses.

Fair market value (FMV). The price a stranger would pay for your asset in an arm’s-length transaction. If you put it up for sale, what would someone pay for it? Try to avoid using sample prices you find on eBay as your source for FMV because you’ll end up with a lower value.

General journal. Within the bookkeeping system, this is where adjustments are entered.

Journal entry. An accounting entry posted to the general journal. Most entries come into the books via money transactions—deposits or purchases. They are entered in the cash receipts journal or cash disbursements journal. However, corrections, depreciation, amortization, the splitting of payments between loans, and interest—all those noncash or correcting transactions—are entered in the general journal. Year-end adjustments are entered on the books using journal entries.

Liabilities. These represent money the business owes, including unpaid payroll and sales taxes accrued at the end of the year, credit card debt, loans, and monies owed to employees or officers. Accrual basis companies will include their accounts payable here.

Nexus. This is a business presence in a state or tax area. See Chapter 12 for a detailed explanation.

Offshore income. Income held in accounts outside the United States. Offshore doesn’t necessarily mean “on an island.” It could just as easily be in an account right across the border in Mexico or Canada. There are some heavy-duty reporting requirements when you have bank accounts with a total of $10,000 or more in them in any year. Look up FBAR and FATCA in the IRS website.

Owner’s capital account. An account in the equity or capital section of the balance sheet that tracks the partner’s, shareholder’s, or member’s ownership interest in the business. When the investor contributed very little money but has received a lot of draws or losses, his or her capital account may be negative. When capital is negative, an investor is usually not permitted to deduct any more losses.

Owner’s equity. See Capital.

Pass-through entities. Business entities that do not pay federal taxes. They pass through their profits and losses to owners, who report the amounts on their personal tax returns. Chapter 3 explains this concept.

Payroll. Wages and salaries. Payroll is not just any money you hand to the workers. Payroll has a specific meaning. If you use payroll to refer to the compensation you’re paying your freelancers within earshot of an auditor, you’ve just turned them into employees. Chapters 9 and 10 cover this topic.

Percentage of completion. Another accounting method. It is a way of reporting income when you’re on a long-term project and receive progress payments. This is used in construction and engineering projects, among others.

Profit and loss statement (P&L). A financial report summarizing a business’s income and expenses, resulting in either a profit or loss on the bottom line. (See Balance sheet.)

Purchase order (PO). A written document letting a company know that someone in authority approved a particular order. It also defines what was ordered and usually includes a promise to pay for a specific number of units at a specific price.

Quarter. When used in financial reporting, generally a three-month period. There are four each year. You’ll often see quarters noted as Q1, Q2, and so on. They usually run as follows—Q1 January–March; Q2 April–June; Q3 July–September; Q4 October–December. This schedule for quarters is particularly important for payroll, sales taxes, and estimated taxes. The IRS, of course, has a whole different schedule for quarters when it comes to estimated tax payments (see Chapter 11). In the financial world, publicly traded corporations release their profit and loss statements each quarter—to the acclaim or jeers of analysts.

Retained earnings. Profits the business has earned that have not been distributed to owners or shareholders. (See Balance sheet, Draws.)

Tax year (also fiscal year). The accounting year established by your business. In general, it should start on January 1 and end on December 31. However, corporations have the option of selecting their own year-end, to simplify accounting. If taxes will be deferred (delayed) more than three months, the IRS may require the company to pay the difference earlier as estimated tax payments.

Terms. The period of time by which an invoice must be paid; may also include a discount code. For instance, 2/10 means if you pay the invoice within 10 days, you’re welcome to deduct 2 percent of the invoice.

Trades. An advertising industry term that describes formalized barter transactions.

Transposition of numbers (also called “transpo”). A mistake that occurs when writing numbers or keying them into your accounting program—when your fingers get dyslexic and two numbers switch places. Instead of typing “976,” you type “796.” The difference is 180. You can always recognize a “transpo” because the digits in your out-of-balance number will add up to a multiple of three. (For instance, 1 + 8 + 0 = 9, which is 3 × 3.)

Trial balance. A list of all the accounts your company uses in its accounting system, with a balance in each account. When you total up the balances in all the accounts, you should get zero.

Wages. See Payroll.

Record-Keeping Resources

Online Glossaries

• The AICPA (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants). http://www.aicpa.org/press/downloadabledocuments/acronyms_and_abbreviations.pdf. Has a glossary of terms, acronyms, and abbreviations.

• VentureLine. https://www.ventureline.com/accounting-glossary/. Offers an extensive tax and accounting glossary.

IRS Publication

• Publication 583, Starting a Business and Keeping Records. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p583/index.html.

Free Bookkeeping and Record-Keeping Resources

• FreshBooks. https://taxmama.freshbooks.com/signup. Basic bookkeeping. Simple, online way to track your time and your income, do your billing, and get paid quickly. It integrates with many apps to make your life easier. The site has a community forum where you can learn—and even meet new clients, perhaps.

• Outright. http://iTaxMama.com/Outright. Bookkeeping designed for sole proprietors. It’s now called GoDaddy Bookkeeping. Why? It’s a good story. Kevin Reeth and Ben Curren used to work for the QuickBooks folks. They realized how excessively complex the software had become for the really small business owner who simply wants to keep track of records. They did such a great job with the system that GoDaddy bought the company. It lets you import information from your online bank accounts, credit cards, and other applications, such as Shoeboxed, PayPal, eBay, and FreshBooks.

Bookkeeping Resources

• One-Write. http://www.one-write.com (double-entry cash journals). This is one of the older manual systems for small businesses. Basically, it’s designed so when you write your checks, the information is duplicated directly into the cash disbursements journal. At the end of each day, week, or month—depending on how many transactions you have—you simply total up each page. Just follow the formula at the bottom of the page to see if you’re in balance. It’s a little old-fashioned, but I remember having more free time when we used this system. You will still need to enter the data into a general ledger. Or have your tax pro do that for you. One-Write also offers a software system.

• Dome. It produces a variety of record books and bookkeeping systems that are inexpensive, including a 13-column pad in a three-ring binder, with tabs for cash receipts pages, cash disbursements pages, payroll journal, and general journal. You can find the products at all office supply stores and at online bookstores, and your tax professional can show you how to set things up. You can find them at most office supply stores.

• Tax MiniMiser. http://iTaxMama.com/EnUSA. Tax MiniMiser allows you to log the usage of vehicles or mixed-use assets. You can use it to track income and expense as a complete, stand-alone, accounting system—on paper.

• TaxPal. http://www.taxpal.net/. A software tool to use with the Tax MiniMiser, or stand alone. It lets you enter mileage and expense data by hand or import it from various apps. It’s still growing and developing and welcoming input from users. The unique thing about this is, it’s built around the questions the IRS asks about each meal or entertainment, trip or deduction. It’s designed to protect you in audits.

º Magical Miles. https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/id817598888. An iOS mileage app that can be imported into TaxPal.

º MileIQ. https://www.mileiq.com/howitworks. The Android app you can use with TaxPal.

• Quicken. http://iTaxMama.com/Quicken. This is a single-entry system with lots of bells and whistles. With its banking and investment tools, it has terrific value for personal use. But don’t use it for business. Buy its big sister, QuickBooks, instead.

• Sage 50c. http://iTaxMama.com/Sage50. This is very popular with larger businesses and accountants but is more complex than QuickBooks. It’s easier to use if you have some accounting or bookkeeping background. Generally, users set it up to work with account numbers, which are harder to use when trying to make entries quickly. The software is slow. I have tried it with various systems, and it is always slow.

• QuickBooks. http://iTaxMama.com/QuickBooks. A full double-entry system for small businesses, QuickBooks is available in many versions, including customized versions for various industries and point-of-sale systems for retail shops. This program can work with online banking systems. Add-on payroll systems are available. When buying the box, instead of using the online version, you may track many companies. It’s one of the most popular systems. Intuit is buying up smaller companies, so a few years from now, it may be the only one left standing. But as improvements are made, it gets more and more confusing to users. Newer versions are not backward- compatible. So to enable your tax pro to review your work, or for you to see your tax pro’s changes, you both have to constantly buy updates, which can be very frustrating. TaxMama recommendation: To avoid the compatibility problem, consider the online version, http://iTaxMama.com/QB_Online. You, or your accountant, can access it from anywhere and make entries even when you’re on the road. QuickBooks does the backups for you. Mac and PC versions are available.

• Xero. http://iTaxMama.com/Xero. A relative newcomer to the scene. But they get it, when it comes to technology. They can make your business life super easy, with lots of drag and drop tools. You can attach documents to your entries for your checks or income. It can make business decisions and audits really easy.

• Acclivity’s AccountEdge. http://www.accountedge.com. This system offers software for both Windows and Mac systems, with accounting software for several countries and currencies. It’s a more sophisticated system, allowing you to add more modules as your business expands to include manufacturing, payroll, and other accounting functions. The company offers free conversions from QuickBooks. (AccountEdge was formerly MYOB.)

• Sage 300c (formerly ACCPAC). http://www.sage.com/us/erp/sage-300. Another step up, this system works best for larger organizations needing a more formal accounting environment. The company offers free conversions from QuickBooks and Acclivity.

• Shoeboxed. http://iTaxMama.com/ShoeBoxed. For those who don’t have the time to record all their invoices, receipts, etc., this is a terrific service. It is especially good for folks who experience total resistance to bookkeeping. Shoeboxed integrates with Outright.com, FreshBooks, and more—and is adding features all the time. In fact, you can even scan receipts directly from your phone.

Tax Resources—Calculators and At-a-Glance Summaries

• CFS Tax Software. https://www.taxtools.com/Default.aspx. This site has an excellent, inexpensive array of tax tools and special calculation tools, including payroll tools, you won’t find anywhere else. Use discount code TaxMama239 to get 50 percent off their TaxTools software.

• Thomson-Reuters Quickfinders Handbooks. http://iTaxMama.com/QuickFinder. Good for daily look-ups on how to handle issues, this book contains worksheets and basic explanations, with index versions for individuals and businesses. Great for at-a-glance information.

• The TaxBook. http://www.thetaxbook.com. TaxMama’s favorite look-up resource. Similar to the Quickfinders Handbook—but better and cheaper. I use the Online WebLibrary in the TaxMama’s Enrolled Agent Exam Review Courses because the subscription includes three years data on individuals, partnerships, corporations, and more. Use code #817 to get a small discount.

Tax Resources—Research and Academia

The following publishers provide tax updates and resources to accounting firms and colleges. You can get a copy of the tax code, regulations, or analyses on any tax issue. They have books for specific industries and entities. Teaching tools and study guides are available, too.

• Bureau of National Affairs (Bloomberg BNA). http://www.bna.com, (800) 372-1033: It provides folios and in-depth analyses of tax issues.

• Wolters Kluwer’s Commerce Clearing House. https://www.cchgroup.com/ (800) 248-3248.

• Lexis Nexis Matthew Bender. http://bender.lexisnexis.com, (800) 227-4908. The original in-depth legal database teamed up with a major analytical publisher. (Super expensive.)

• Thompson-RIA. http://store.tax.thomsonreuters.com/accounting, (800) 950-1216. Publishes in-depth analyses of tax and accounting issues.

• TaxMama’s Quick Look-Ups. http://iTaxMama.com/TM_QuickLookUp. You will find all kinds of useful reference materials, webinars you can replay, e-books, and more.

• Your Business Bible. http://www.yourbusinessbible.com. Look for worksheets, printable checklists, and other goodies and resources.

1 http://www.computerweekly.com/feature/Apollo-11-The-computers-that-put-man-on-the-moon.