13

TAX NOTICES, AUDITS, AND COLLECTION NOTES

Blood’s not thicker than money.

—GROUCHO MARX

This chapter will walk you through some of the routine or terrifying interactions you will have with the IRS. Whenever you get notices about audits or owing money, don’t just ignore the notices. Always address them. If you are afraid or uncomfortable about dealing with the IRS alone, engage the services of a good local tax professional who understands how to handle audit or collections issues. Not all tax pros do. Ask them to tell you how much experience they have—and if they’ve been successful. If they complain about all their problems with the IRS, move on. The real pros know how to get right to the key people who can help you.

Dealing with Basic Tax Notices for Individual Returns

When you file a tax return—or don’t file—sometimes, there may be errors or you will have a balance due. The IRS has a series of standard notices it sends you. Each notice has a little CP code on the top right-hand corner of the first page of the letter. CP stands for “computer paragraph.”

The notices are issued in a particular timed sequence by the IRS computer. If you don’t respond in time for someone to receive your response and key it into the computer, it will automatically spit out the next notice. If you are mailing a response right at the end of the response period, call the IRS immediately. Ask the agency to put a hold on any collections actions until it receives your information. Let me repeat—call the IRS. Don’t just hope it will get your response in time. And when you call, always be sure to write down the name of the person you speak with, his or her IRS employee number, and the date and time of the conversation. (The person will give you that information at the beginning of each conversation. But he or she will say it quickly, so don’t overlook it. If necessary, ask the person to repeat the name slowly—and to spell it for you.) Follow up with a written note to the IRS or that employee, summarizing your conversation.

Incidentally, if you get the right person (or the right group), he or she may be able to accept your information over the phone and the fax. If a person has helped you, it’s always nice if you send a thank you letter. Remember, even though the agency is the big, bad IRS, you are dealing with real live people who have jobs and families. A nice letter in their file does two things. First, it could help them get a raise or a promotion. Second, a copy stays with your file, too, and alerts the IRS that you are a nice person. In the future, that could work in your favor.

The IRS has added many more notices to its repertoire. It has also been redesigning its notices. A San Francisco Chronicle journalist and I were puzzling over the changes. We weren’t sure they were really improvements. But the IRS is trying.

A Key to Certain IRS Notices

To look up your notice, look for the notice number or letter number (usually CP-[something] or LTR-[something]) in the top, right-hand corner of the letter. Then come to this page on the IRS website and enter the notice or letter number—http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_Notices. Incidentally, some of these notice numbers come in a series, like CP12, CP12A, CP12E, etc. Below is a list of common notices you can expect to receive. There are lots more—and a whole set of notices just for businesses.

• CP05–CP06 Series. Your income and Premium Tax Credits. Your refund is being held up while the IRS verifies your income, and whether or not you qualify for the Premium Tax Credit—or have to pay it back. The IRS is cross-referencing databases to verify your earnings. Your refund might be held up for as much as two months (or more) due to the extensive fraud in the system.

• CP08—Additional Child Tax Credit. You may qualify for the additional child tax credit and be entitled to some additional money.

• CP11—Changes to Tax Return, Balance Due. Generally based on the math in your return. You probably owe this. Pay it.

• CP11A—Changes to Tax Return and Earned Income Credit, Balance Due. Generally based on the math in your return and information the IRS has cross-referenced about your dependents. Or you have not provided information about the dates of birth of your dependents. Call the IRS to see if you can provide better information about your dependents to save your earned income credit.

• CP12—Math Error—Overpayment of $1 or More. You still have a refund coming, but it may be lower than you expected. Look for child tax credit adjustments or disallowed dependents because of a Social Security number mismatch. You have 60 days to respond or pay. Compare the numbers on the notice with those on your tax return. The IRS’s adjustment may be wrong. Or you may never have gotten a check from the IRS. Respond in writing before the deadline, with your explanation.

• CP14—Balance Due, No Math Error. This is the computation of the underpayment penalties and interest to your tax return. It may also include late filing or payment penalties. You have 21 days to respond or pay. You can reduce the underpayment of estimated tax penalty if most of your income was received toward the end of the year. Use the annualized income installment method of computing your penalties, found on page 4 of Form 2210, Underpayment of Estimated Tax by Individuals, Estates, and Trusts.

• CP23—We Changed Your Estimated Tax Total, You Have an Amount Due. Perhaps one or more of the checks you thought were estimated payments were something else (perhaps payments for last year’s tax). It’s also possible that you sent a check but didn’t write the correct year, form number, or Social Security number on it. The IRS may have your money but hasn’t applied it to any specific year. Find your canceled check and make very clean photocopies of both the front and back. Send the check to the IRS with the notice and your explanation. You have 21 days to respond or pay.

• CP24—We Changed Your Estimated Tax Total, You Are Due a Refund. Quite often, you either haven’t recorded a payment to the IRS or didn’t remember that you applied last year’s refund to this return. The second page of the notice will show a list of the payments and dates the checks were received by the IRS. There is no need to reply. By the time you get the notice, the IRS will already have sent the check. However, it may be giving you credit for a payment you intended for a different year. Since you’re getting the money back, you might not care. But it may involve an estimated payment that you had made on time for the current year—and now you’ll get hit with underpayment of estimated penalties. To avoid this problem in the future, make sure you always write the following three pieces of information on each check you send to any government agency. TaxMama’s acronym FYTIN may help you remember:

º F. The form number.

º Y. The tax year you’re paying (use a separate check for each year).

º TIN. The taxpayer identification number (TIN)—your Social Security number (SSN) or employer identification number (EIN)—to credit with this payment. If you are paying money in toward a married filing joint return, list both SSNs.

If the IRS sends you a refund for a payment that was intended as an estimate and you shouldn’t have gotten the refund, do this: (1) Write “VOID” on it. (2) Make a copy. (3) Send it back to the IRS, via Certified Mail with proof of delivery, with a letter explaining that you want that money applied to your account. Specify the tax form and year. This may prevent penalties for a tax you did mean to pay. Better yet, stop mailing in your estimated tax payments. Use the IRS’s DirectPay system—https://www.irs.gov/payments/direct-pay.

• CP 45—Unable to Apply Your Overpayment to Your Estimated Taxes. The IRS found math errors in your tax return; or you included withholding or estimated tax payments that were not on record. That means your estimated taxes will be underpaid. Check your records to see if you made a payment last year that the IRS does not show. If so, contact the IRS and send copies of the canceled check or other proof of payment. If it is not an IRS error, make additional payments using Form 1040-ES.

• CP 49—Overpaid Tax Applied to Other Taxes You Owe. The IRS will send you this notice if you owe money for prior years. You might also get one of these if you owe back child or spousal support, state income taxes, or motor vehicle fines. These are called offsets. The IRS will also grab your refund if you’ve defaulted on student loans or owe money to the Social Security Administration. The notice will spell out which years or debts are being paid. Often, the money isn’t staying with the IRS. When the money is sent to another agency, you’ll have to get a release from that agency. When that’s the case, don’t even waste your time trying to get more information about the outstanding debt from the IRS. It won’t have it. You’ll have to go to the source, for instance, the motor vehicle department, the district attorney’s office, and so on. You’ll need to contact the agency that initiated the lien on your refund. Sometimes you get an unpleasant surprise, learning about an old IRS balance you didn’t know about or forgot. Track down the details. While the IRS may have only grabbed $39 this year, don’t just shrug it off as being too small to matter. It might take $3,000 next year.

• CP53—The IRS can’t provide your refund through direct deposit, so they are sending you a refund check by mail.

• CP90—Final Notice—Notice of Intent to Levy and Notice of Your Right to a Hearing. You will only get this notice if you have ignored all the other notices. You have 30 days to respond or pay. If you know you owe the money, call the IRS to work out a payment plan or an offer in compromise (OIC). Ask the IRS to put a hold on the collections activity until you either file the OIC or start the payment plan. Once you’re on the plan, the IRS will hold off as long as you’re current on your payments.

• CP91—Final Notice Before Levy on Social Security Benefits. See CP90 above. The IRS will grab up to 15 percent of your Social Security benefits if you don’t communicate with them and start dealing with your outstanding taxes.

• CP161—No Math Error—Balance Due. This is the business version of CP14.

• CP501—Reminder Notice—Balance Due. You have 10 days to respond or pay.

• CP504—Urgent Notice—We Intend to Levy on Certain Assets. Respond within 10 days or lose your state tax refund. The IRS will also start locating and levying bank accounts, wages, or other funds it knows where to find. (If you have a government contract or 1099s have been filed under your Social Security number—watch out.) Note: If your bank or employer calls to tell you your wages or bank account has been levied or garnished, don’t panic. The bank and your employer must hold those funds for 20 days to give you time to fix the problem. How can you solve the problem? First get a copy of the levy notice they received. Then call the IRS immediately. If you can set up a payment plan or get the agency to agree to give you some time (typically 30 to 45 days), you’ll be able to get the IRS to release the levy.

º Good news. The bank levy only lets the IRS grab the money in the account on the day it receives the levy. Any money deposited afterward is safe—until the next levy.

º Bad news. If wages are garnished, that deduction continues until you get the IRS to release the garnishment or until you pay the balance in full.

• CP523—Notice of Default on Installment Agreement (IA). When you signed the IA, you gave the IRS your bank account numbers and the permission to levy if you didn’t make your payments. Now it will. Call immediately. (See CP90 above.) You have 30 days to sort this out. If you have a problem, the IRS is willing to help you modify your IA or put it on hold if you are unemployed or disabled.

• CP2000—Notice of Proposed Adjustment for Underpayment/Overpayment. This notice results from the IRS’s computers matching up all the W-2s, 1099s, 1098s, and K-1s issued under your SSN. Quite often, the notices are wrong. Or they are reporting stock sales on which you had losses anyway. The information is reported somewhere on your tax return. Review the notice carefully. If the IRS is wrong, call the phone number on the form immediately and ask for another 30 days to respond. That way, if it takes a while for your response to reach the IRS, it won’t already be billing you. When the IRS is right, it’s because you left off employment income (perhaps a brief job early in the year) or dividends you forgot about. If the IRS is correct, just pay the bill. You don’t need to file an amended return. You have 30 days to respond or pay. However, if there was an error, you must file an amended return with your state. Sure, your state will get notified about the error from the IRS. But some states will waive the penalties if you file the amended return yourself within six months of the IRS revision.

• LT18—Reminder—We Have Not Received Your Tax Return. The IRS’s records show that you have income and should have filed a tax return for the year. Prepare and file the return. Or if you have already filed it, clearly, the IRS doesn’t have it. So send it again. Be sure to stamp it as a copy (or write “Copy” over it). Sign it, dating it the same date that you originally filed it. If you never filed a return—prepare one and file it now.

More Notices

We don’t have room to list all the notices. You will find the current list on the IRS website at http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_Notices.

Anytime you get a notice, the IRS recommends you call the phone number listed on the letter within the deadline shown on the letter. Yes, sometimes you only have a few days because the notice was mailed late. The IRS computer doesn’t know when it was mailed, so it will take the next action on schedule. Don’t argue with the IRS staff person who answers the phone. He or she isn’t at fault. Be pleasant and polite, and the person will be more apt to help you.

IRS Audits

Sooner or later, just about all businesses get audited. Not that often, though. The IRS does happen to be behind on its audits. But it released an announcement in April 2004 about rolling out its new, more aggressive audits of businesses—which are still going on.

During the IRS’s fiscal year 2002 (covering your 2001 tax return), the IRS audited less than half a percent of all tax returns filed.1 That makes you feel great, right? Think again. In fiscal year 2014, IRS audit activities increased and became more focused due to the tax gap. Nearly 5 percent of tax returns with an adjusted gross income of zero or less were audited.2 Nearly 33 percent of tax returns showing over $1 million in income were examined (16.22 percent over $10 million). In between? About 5 percent of tax returns with incomes in the $200,000 to $1 million range. The average tax return, between $1 and $200,000, was hit about 0.5 percent to 1 percent of the time.

With the tax gap being in the hundreds of billions of dollars, the IRS believes that a large part of the unreported income, or underpaid taxes, is coming from small businesses. In fiscal year 2015, the small business audits on both individuals and S corporations have been increasing because the IRS knows it can assess taxes due to the many failings of small business and their accounting practices.

Why am I boring you with these statistics? Because it will help you with two areas of your business. First of all, it will help you determine what business format you want to adopt. Second, it will help you understand just how much risk there is of your transactions being scrutinized. So if you’re thinking of doing something questionable—you know the risk.

What Is Most Apt to Attract the IRS’s Attention?

As a small business, inconsistent information on your tax return will generate an audit. For instance:

• You have an office in home, but you are also taking a deduction for rent. You can’t have both. At least not without an explanation. (See Chapter 7.)

• You are an S corporation with a profit, but no officer wages. Major red flag! (See Chapters 3 and 9.)

• Your adjusted gross income is very low, but you are able to afford to live in a high-rent district (zip code), with expenses that substantially exceed your reported income.

Anticipating an Audit: Laying the Groundwork

Knowing you’re being audited is usually simple. You get an audit notice. If you’ve moved frequently and haven’t updated your address with the IRS by filing Form 8822, you might not have gotten the notices. If this happens, some nice Fed in a dark suit might come knocking on your front door. You’ll go running out the back door to call your tax professional. (Yes, one client of mine really did that. It’s not a good idea.)

Whether you deal with the audit yourself or turn it over to a pro, you need to understand the process. After all, you’ll be gathering all the documents. Following the guidelines here will save you hundreds of dollars off your professional’s invoice.

Your Return Is About to Be Scrutinized

What will the IRS want to know? The primary goal is not to see if you have receipts for the expenses you reported on your tax return. What the agency is really looking for is unreported income. You’re about to get some insider information on how to handle audits.

Unless you have a simple tax return, don’t handle the audit yourself. Send a seasoned tax professional to the audit instead. In addition to the paperwork, if you are there, the auditor will be looking you over during the audit. Avoid that part of the scrutiny. Let them look you over on paper, instead. The examiner will focus on five fundamental audit issues:

1. Your financial lifestyle

2. Your standard of living and reasonableness of business operations costs

3. Your spending habits and new purchases (conspicuous consumption)

4. All your bank deposits

5. Whether you reported all income from 1099 or W-2 reports

If these factors don’t match your tax return (or industry practices), the IRS will suspect unreported income, inflated expenses, or worse, though your source of funds may simply be nontaxable income or savings. When you’ve done nothing wrong, you don’t want your intermingled accounts to get you into trouble.

Remember, the IRS is the nation’s tax collector. It knows that people will do anything to reduce their taxes—even something illegal. The IRS’s main focus is no longer on substantiating expenses—although it will still make sure your expenses are legitimate. The IRS is serious about identifying unreported income and making the audits profitable.

With so many electronic tools and information-sorting technology, it has become easy to pinpoint the right tax returns for audit. Before it sees you, or your representative, the IRS can run a search of your name or your company name on the Internet.

The IRS can find your press releases or newsletters, puffing your company’s successes. It can find your marriage, engagement, birth, and death notices. If you throw a really big confirmation, bar mitzvah, or wedding, chances are your pictures and announcements are online. You may even have a website. Consider this: you’re probably giving the IRS the information yourself. So make sure that the information you’ve put into the public arena matches what the IRS sees on your tax return.

Don’t believe me? Google your name. Now Google your business name. See?

Where Else Will the IRS Look for Information About You?

Take a look at Table 13.1. You’ll find a whole list of sources the IRS can use to find out about you and your industry if the agency is uncomfortable with your audit. Typically, before an audit, the examiner will pull all the information the IRS has on you internally. (See the first section of Table 13.1.) Sometimes, the examiner doesn’t have time to get everything, so he or she asks you to bring things—like prior-year returns. If you notice errors on prior-year returns, don’t fix them. Sooner or later the examiner will pull the actual return that was filed—and you want them to match. Right?

TABLE 13.1 How the IRS Knows More About You Than Your Return Shows

Incidentally, most tax professionals will tell you that we rarely bring a prior-year tax return to a client’s audit. Generally, we are able to handle the average (very) small business audit in one meeting and settle it—if we have done our homework.

The IRS will only dig into the sources in the second section of Table 13.1 if it feels you’re holding back information. If the examiner doesn’t believe your story about that $10,000 deposit being a loan from Dad, he or she will start digging into city, state, or credit resources to see if there is evidence of business income you’re not reporting.

Remember, the IRS is the arm of the U.S. government that caught Al Capone, Wesley Snipes, Christina Ricci, and Richard Hatch (from the TV show Survivor). The agency has access to substantial internal and external resources about people—especially in today’s computer age.3

How Do You Overcome the IRS’s Advantage?

In order to be the most successful in an audit, make sure your representative knows as much about you as the IRS knows. You never want your representative going to an audit only to have him or her learn that the IRS has communications from you that your pro is ignorant of, or that the IRS knows about income or bank accounts that your tax pro doesn’t know about.

Be sure to disclose all income sources to your pro. Pull a copy of your own credit report to see what the IRS will find.

If you have unexplained or suspicious transactions, you may want to consider hiring an attorney instead of hiring an enrolled agent or certified public accountant.

Keep in mind: your reputation and credibility with the IRS are your best assets if you want to minimize audit damage. If you’re caught in a lie, the IRS won’t help you reduce the impact of your errors.

If you have inadvertently not reported income, there may be a good reason for your oversight. If the IRS understands it wasn’t intentional, the agency may help you avoid fraud and other penalties. Really. I actually had an IRS revenue agent (auditor) help me with a partnership audit. She made me look really good to the partners. (I have lots of stories of getting help from the revenue agents or examiners during audits.)

What Will Happen During the Audit?

First, you should have received a letter telling you what items on your tax return will be examined.

Look carefully at the pages that outline what the IRS wants to see. If you don’t understand the letter, you may call the IRS office before you get there and ask for clarification. That ought to shock the office. Few people ever do that besides tax professionals.

During the audit, your examiner will ask a series of questions about you, your past audits, your personal circumstances, and so on. Answer the questions as honestly as you can. Never lie, and don’t argue or evade the questions. The examiner is just filling out a form. If you don’t know an answer, say so.

Note: When you have a tax professional do this for you, there is one question we generally don’t answer. We don’t give the IRS your phone number or other contact information. When we have your power of attorney to represent you, we are there to prevent the IRS from bothering you.

Once finished with the general questions, the auditor will focus on the tax return. The first concern is how much income you received. After that number makes sense, then he or she will look at your expenses or the other areas under consideration.

The auditor will have a printout of the 1099s issued to you. Those 1099s show interest-bearing bank accounts and money market accounts, with account numbers. The IRS will already know about your accounts, so bring all the bank statements requested to the audit.

The Most Important Item to Prepare—Proof of Cash

The auditor will look at your income first. To see what the auditor will see, prepare your own proof of cash. When overlooked by taxpayers or tax professionals, this one step can cause more trouble in audits than any other.

When the IRS takes all your bank statements, from all your accounts, and adds up the deposits, what will it find? If you’re as casual about what goes into your bank accounts as most people, the IRS will find much more money showing up as deposits than you ever earned.

The total deposits will include loans, gifts, cash advances, inheritances, repayments of loans by family or friends, insurance proceeds . . . Are you getting the picture? In fact, one of the biggest sources of bank statement inflation is transfers from one account to another. If you leave it up to the auditor, it will look as if you did not report income.

What happens if you leave it up to the IRS? Let me tell you about George.

George owned about 25 low-income residential buildings when he got audited one year. He went to the audit without any real preparation. When the auditor did the proof of cash, she discovered more than half a million dollars of unreported income. The tax, with penalties and interest, was more than $300,000. His tax preparer went back to the IRS and requested an audit reconsideration. While the tax pre- parer didn’t do a great job preparing his second audit, he did get the tax balance due cut by $20,000. That still left $280,000 due. Worse, the state of California would probably add another $100,000 when it was notified about the audit results.

George got lucky. He ran into a sympathetic IRS collections officer—Marta—who had an audit background, too, and listened to George when he insisted that he never had that kind of income. Marta helped us to find the obvious transfers and nonincome items. We found several, including proceeds from mortgages when he refinanced two buildings and pulled cash out. Unfortunately, there was still $300,000 to identify. George was adamant it wasn’t income. We found the answer when George remembered that he had borrowed money from the bank using his certificates of deposit as security. We couldn’t provide records of the transactions. He had none. George’s bank had burned down in the Rodney King riots in April of 1992.4

How did we convince the IRS that the $300,000 wasn’t income? We located his old bank manager and had her write a letter saying that she knew he made a regular practice of borrowing against those certificates of deposit. The IRS dropped the rest of the assessment.

In George’s case, if he or his tax pro had simply done the proof of cash during the initial audit, they’d have known about the large discrepancy before the audit. They could have rescheduled the audit until he tracked down all the nonincome items. It would have saved him thousands of dollars of professional fees. More important, George would have avoided the stress and fear that comes when the IRS keeps trying to attach your bank accounts, wages, and investment accounts for a year or two.

While this story might seem a bit dated, the concepts are important—and quite current. In fact, trying to reconstruct data is a big part of what tax professionals do when clients are in trouble. This is especially important when dealing with people who have not filed tax returns for many years—often because they were missing information and didn’t know how to proceed. If you need more ideas on how to reconstruct missing information, drop by CPELink and take the course I am teaching with Kris Hix, EA, NTPI, called Cohan or Bust: How to Reconstruct Missing Information—http://www.cpelink.com/teamtaxmama.

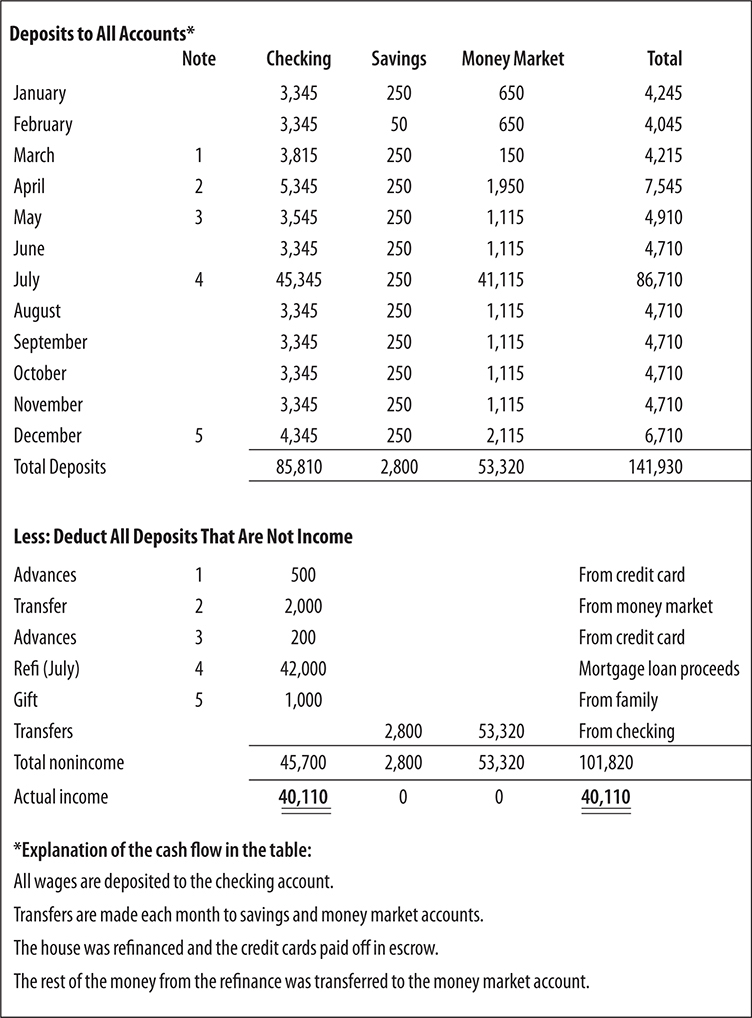

So how do you prepare this nifty proof of cash? It’s really easy. See Table 13.2 for step-by-step instructions.

Now, take a look at an example in Table 13.3. Prepare it yourself on paper or using spreadsheet software. It makes no difference. Just do it neatly.

TABLE 13.3 Proof of Cash Spreadsheet

Looking at the “Total” column, the IRS would have determined that your income was $141,930 based on adding up all the deposits to all the accounts. Look at the actual “income” in the “Total” column. You can see that the net paycheck amounted to $40,110.

Now you understand how the IRS can think you have $100,000 more income than you really do. That’s why it’s so important to be prepared.

OK. You’ve established that you didn’t deposit more money than you reported on your tax return. What’s next during your audit?

Time to Work on Expenses

In ideal situations, when you have a business, you have a profit and loss statement and a balance sheet, along with a detailed general ledger printout. Or you could go in with an accordion file with all the receipts neatly arranged into categories—with each batch of expenses totaled with adding machine tapes attached. You can probably do this when you have receipts that only belong in one expense category. But if the receipt or check needs to be split among several categories, what are you going to do? Think of credit cards. Each statement has auto expenses, office supplies, meals, travel, and entertainment. Unless you can make several photocopies of each statement to attach to each batch, you have a problem.

That’s why it’s important for you to do your bookkeeping before you go to an audit. Do it, even if you never bothered doing it before. (See Chapter 4 for more on record keeping.) Sure, your expenses might come out differently than they appear on the tax return. Don’t worry. If your overall expenses are the same, or similar, you’ll be fine.

What If, After the Bookkeeping, Your Expenses Are Still Way Off?

You’ll need to find ways to come up with additional expenses—legally. Look here:

• Credit cards. Did you enter all the business expenses from each statement? From each credit card? Do you have a personal card that you sometimes used for business? Remember to include those business expenses. Did you skip December’s bill because it has a January date on it? Grab that bill. If the charges were in December, you may use them.

Did you have bad credit and have to use someone else’s card? Get the other person’s statements—and some of the receipts that show you signing for the charges. You may need some proof, but if you show the IRS examiner your really bad credit report, he or she might just smile and understand.

• Cash. Did you pay for things using cash in the normal course of the day but there are no receipts? Make reasonable estimates. Look back through your appointment book. If you traveled, make a list of the dates and places. List all the tips you gave out each day. List the cab fares, tolls, public transportation costs, and so on. Did you pay for parking, meters, pay phones? Using a spreadsheet, just list all the different out-of-pocket expenses. Be sure they don’t add up to more than the cash you drew from your ATM or bank account.

For expenses where the IRS permits you to use standard amounts (auto, mileage, meals, and travel per diems), compare the actual costs with the standard rates. Often, I have been able to bypass a detailed scrutiny of the expenses via one of these methods. Tables with allowances for several years are available on the Internet. Chapter 6 tells you where to find them.

If you’ve pulled everything together and you still find discrepancies—call a tax professional. Find a tax pro with experience in audits, bookkeeping, and your industry. A professional may be able to read your mind and help you remember what you were thinking when you originally came up with the numbers on your tax return.

Unless, of course, you either simply made them up—or lied.

Still coming up short? You’ll know before you go into the audit what you will lose. It won’t be so intimidating when you already know the worst case.

TaxMama’s Tips Do Work!

A client of Rita Devlin Zapko recently faced an IRS audit. Rita reports the result: “Thanks in part to your prep, I just had a client dazzle them with organized, reconciled information on his first retail audit. The IRS accepted his past 6 months’ records, with zero assessment and agreed not to open 2013–2015.”

What If You Don’t Have Any Receipts?

The tax code operates on the “ordinary and necessary” principle. IRC §162 allows the deduction of ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred in carrying on a trade or business.5 If it appears that an activity was entered into for profit, the rules of IRC §162 are applied to each expense.

While the IRS is not always excited about the application of this principle, the courts have ensured that we taxpayers get the benefit of it. There’s the old Cohan rule from 1930, when the appeals court decided in favor of entertainer George M. Cohan.6 Cohan had deducted all his travel, meals, and business expenses without producing receipts. Can’t you just see George M. riding around the country on rickety cars, buses, and trains, with his trunks full of vaudeville gear, costumes, props, and all, and dragging around another huge trunk just for receipts and accounting records? Well, neither could the court. It determined that if the expenses make sense for your line of work, profession, or trade, you should be entitled to reasonable deductions in line with your industry—even if you don’t have receipts.

Due to abuse of this provision, the courts have ruled that they will not allow Cohan if you have not made every reasonable attempt to re-create your records. If you make no attempt at all, don’t count on Cohan to bail you out.

I tested the theory with a client who also happened to be an entertainer. Barry was audited a couple of years ago for his $50,000 worth of business expenses. Well, like good old George M., Barry had nary a receipt for all his travel, meals, and so on. Besides, he had poor credit and paid for everything in cash. So we couldn’t reconstruct his expenses using credit card statements. Knowing we needed to provide proof of the travels and costs, I did a lot of work. Using various outside documents, like the TV Guide and the postcards he sent me from the road each week, I was able to prove his travels. Using the IRS per diem rates (see Chapter 6), I established reasonable costs. The IRS accepted all the expenses, with no receipts, and better yet, no conflict. It was resolved at the auditor level, right in the office. Of course, it did take a little negotiating.

Negotiating

During an audit, you can negotiate, to some extent, on all levels. You must have a basis for your request. In George’s case, discussed earlier, we were able to get the IRS to believe that $300,000 wasn’t income because we were able to prove a pattern of behavior. In exchange for a letter from a banker (considered third-party testimony or evidence), I was able to negotiate away $300,000.

Having a basis for your request may involve doing research on similar issues and being able to bring copies of those cases to the auditor. It may involve getting statements from objective third parties. It may involve agreeing to give up one set of expenses so that you can keep others that are more important to you in the future. For instance, I had a client whose tax return included an in-home office, while he was an employee, and $15,000 worth of garments he’d bought as samples. Alex was willing to give up the in-home office for that year, as long as the full amount of the garments was accepted as a deduction. He needed those garments as a deduction to support a Tax Court case. We didn’t care about the employee office in home, because the following year he was a full-time independent contractor—and worked from home full-time, in his own business.

The IRS won’t do it just because you ask. Not even if you’re really cute.

TaxMama’s Three Basic Rules of Tax Negotiating (KGB)

1. Know. Before you start negotiating, know exactly what you want to accomplish. (The IRS doesn’t need to know that—but it’s critical that you have it defined in your own mind.)

2. Give up. Have something to give up. (In exchange, be so thorough in your audit preparation that you find all expenses you overlooked. Look at missed itemized deductions—always a good source of errors in your favor!)

3. Backup. Give the auditor or appeals officer something tangible to put into the file to support your position. Providing backup documentation saves the auditor or officer time and makes the person look good to his or her superiors on review.

In George’s audit, we weren’t able to prove that the last $133,000 of deposits were transfers or loans. Since I was able to prove that there was a consistent pattern of behavior, I could negotiate with the IRS about the rest. The IRS would accept the logic and conclude the sum was not income in exchange for my preparing a worksheet with an explanation to provide the auditor for his file. It gave him an excuse to accept my position that the deposits probably were not income.

Office auditors have the discretion to decide what documentation is acceptable. They have to believe the information they see is adequate. Be sure to make an extra set of copies of all the schedules and work papers for the auditor’s file. It provides documentation and makes him or her look better when superiors review the auditor’s determination. Besides, the auditor can write notes on it, too.

Audit Reconsiderations, Appeals, and Tax Court: Some Brief Words

An audit reconsideration7 may be granted when the IRS agrees to reopen an audit that has already been completed and is past all the deadlines for protest on the local level and in Tax Court. It is not an appeal. The audit typically goes back to the same level of examination, often the same office that conducted the original audit. The IRS will not give you reconsideration if you have already signed off, agreeing to the original audit. You must have additional information that wasn’t presented at the first audit. The IRS will also give you this opportunity if you didn’t appear at the original audit. At the time you request the reconsideration, you’d better have at least 80 percent of your material ready. You generally get one shot to present your case. So prepare it well. While the IRS rarely agrees, you can get audit reconsiderations. First, you must have the audit report, generally a Form 4549. If you were working with an examiner, ask him or her for help. If you no longer have that contact information, call the IRS’s main phone number at (800) 829-1040 and make the request. If you still have a contact name, ask the auditor’s group manager for the reconsideration. If that doesn’t work, read this IRS brochure on audit reconsiderations—IRS Publication 3598—https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p3598.pdf. It will tell you what steps to follow. Pick up a copy of IRS Form 12661, Disputed Issue Verification—https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f12661.pdf. This is where you can outline the parts of your tax return you want the IRS to review—and explain what additional supporting documents you have. The brochure tells you where to submit your request and how to proceed.

Naturally, if you get turned down, you won’t be happy. But if you’re really not in the right, drop it and move on. But if you know that you are justified asking for the reconsideration—move your way through the chain of command:

• Write to the branch chief.

• Have your tax professional contact the Practitioner Priority Service (PPS). (It’s a special hotline for the tax professional community.)

• Contact the Taxpayers Advocate at (877) 777-4778.

• Make an appointment at an IRS Problem-Solving Day or Open House.

• Contact the Small Business/Self-Employed Operating Division.

• Contact the deputy director, Compliance Field Operations.

• Contact the director of the IRS.

• Contact your U.S. senator or U.S. representative—or all of them. Sometimes, the only thing that will work is political intervention.

Don’t ever give up. There’s always somewhere to go when you disagree with an audit and you know that you are justified. Sometimes, if it’s worth the fight, you will simply have to pay the assessed taxes and file a claim in a federal court to get heard. That’s the hard way. Not only do you have to pay the taxes, penalties, and interest first, you will probably also face hefty legal fees.

Decide if the cost to fight your battle is worth what you will win. Sometimes, it’s cheaper just to give in to the IRS. But if it’s really a matter of principle and all avenues fail, you may want to look for an advocacy group to take on your case. Sometimes what’s happening to you is happening to enough other people that it’s worth setting up a class action suit or rewriting legislation. You just might end up settling a landmark case—like Edie Windsor v. Commissioner,8 which forced the federal government to recognize same sex marriages for tax purposes.

Should You Use Appeals Only as a Last Resort?

Some tax professionals find the appeals process is sometimes easier to deal with than the IRS’s auditors. While all auditors must have college degrees, the degree does not necessarily have to be in accounting or taxation. Sometimes the auditors are not as well trained as we would like. With the IRS hiring thousands of new employees in this decade, expect to see a lot of people new to auditing.

By the time the IRS agents get promoted to the appeals level, they have extensive field experience, education, training, and the ability to use and understand tax research and research tools. (Currently, the IRS has started to hire tax professionals from outside the IRS. These are seasoned EAs, CPAs, and attorneys with years of representation experience.) You are dealing with a seasoned professional who has more decision authority than the office auditor and many field auditors.

The goal of the Appeals Office is to settle cases without litigation. The appeals officers evaluate your case’s strengths and weaknesses with an eye to how your case will stand up in court. They will pull the relevant court cases, decisions, and precedents (or at least the items the officers think are relevant). Ask them for their citations when you meet. Most important, have your own research ready. Give them a copy of your cases (not just the citations to cases) with your points highlighted. It will enhance their willingness to cooperate with you. You’ve done a big part of their job, and they have objective documentation, in your favor, to put into your IRS file.

Remember, an appeal is not about supporting expenses. It is about tax law and precedents. If deductions were not substantiated during audit, expect the appeals officers to kick the audit back to the original auditor to finish. This is now a nationwide policy called AJAC—Appeals Judicial Approach and Culture.9 If you couldn’t resolve it at that level, do you really want to go back to the field office?

Most tax professionals use the Appeals process to their advantage. So can you. When confronted with a particularly troublesome auditor and a group manager who will not intervene, a tax pro would simply call a halt to the whole process. I’d tell the IRS to post its adjustments and walk away.

Before you do that, there is one thing you must take great care to do. As a result of the Appeals current policy, Appeals will no longer accept any new documents about income, expenses, worksheets, bank statements, and so on. If the audit division didn’t have those documents in the file, Appeals won’t accept them from you. So . . . gather up all the documents and records that you feel you need in order to prove your case and ship them off to the auditor you’ve been dealing with. Be sure to make two sets of extra copies before sending them. And send them with proof of delivery. One of the extra sets is for you. The other is for Appeals if the field office loses (or claims not to have received) your documents. This way, you won’t be bringing Appeals any new documents. And if the original exam group refused to consider your proofs, you can now insist that the Appeals office look over the information.

Why is this step so important? For two reasons. First, Appeals won’t look at that mass of data if the examination office has never had a chance to look at it before. Second, by giving the IRS everything it needs to understand your case, and by cooperating with it at every level of the investigation, you have now officially shifted the “burden of proof” to the IRS. Now, if you were to take this case to Tax Court, the IRS will have to defend its position, denying your expenses, or increasing your income. It’s the law—IRC §7491.

Then, I’d do one of two things:

1. Request fast-track mediation. This is handled by the Appeals Office. Fast-track mediation is rarely used, even now. The Appeals Office would like to see it used more often. The Appeals officers will work intensely to reach a resolution at that meeting with you and the original examiner (and perhaps the auditor’s manager). You can find more information about this program at http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_FastTrack.

2. Wait for the audit determination letter (30-day letter). When it comes, it tells you that you can request an Appeals hearing. If you haven’t already, get a good tax professional involved. He or she will do a more efficient job at this level.

When writing the letter requesting the Appeals hearing, briefly include specific areas where the auditor is incorrect and outline the documentation you are going to provide for this hearing. Do not include a harangue of the auditor’s bad qualities or what’s wrong with the IRS or the system.

Meanwhile, get all your Appeals documentation together. You already have all the support for the unresolved income-expense issues. Now, you must do in-depth research on the tax law issues involved. This is where all that work you did on your business plan will pay off. If you have losses, the business plan will prove that wasn’t your intention. But things do go wrong.

Getting Your Case to Tax Court

If you’ve missed your opportunity to go to Appeals after the 30-day letter, wait for the 90-day letter (Notice of Deficiency). Owing less than $50,000 means you’re eligible to file your petition as a small case. But filing as a small case means you cannot appeal the decision if you lose. So, that may not be your best option. You’ll find the most current U.S. Tax Court Petition Kit online at the U.S. Tax Court’s website, http://www.ustaxcourt.gov/forms/Petition_Kit.pdf.

You may work with an attorney, a CPA, or an enrolled agent (EA) to represent you. With a CPA or EA, you’ll need to sign the petition yourself (in pro per). The CPA and the EA are not admitted to practice directly in the U.S. Tax Court unless they have passed the U.S. Tax Court exam. (Only 84 tax professionals have been admitted since 2000,10 and they have the letters USTC after their names.) So why do you want the EA or CPA involved, if he or she can’t practice in the U.S. Tax Court? Because the case will get kicked back to Appeals before the Court will hear it. That’s when your EA or CPA can step in. He or she will handle the Appeals meetings for you. Tax Court cases usually get resolved at this level. I’ve resolved all my clients’ U.S. Tax Court cases without ever going beyond Appeals. In fact, I have been teaching tax professionals how to handle these cases for over a decade. However, be warned. Do not prepare your own U.S. Tax Court petition, or work with an EA, CPA, or attorney who does not have extensive experience with these filings. The most common error when preparing these petitions is that amateurs omit key issues from the petition (like penalties, interest, certain deductions, or credits). If they are not included in the petition in the first place, you cannot add them to the case later.

Reading many Tax Court decisions, it’s clear some cases only went to the U.S. Tax Court because the taxpayers were really rude or unpleasant to Appeals—or their representative wanted to make some extra money. There are also those cases that look simple but were pushed up to U.S. Tax Court to establish a precedent.

Strategy: Use as many of the 90 days as you can to get your records and research as ready as possible. Send your petition in at least 10 days before the end of the 90 days. Enclose the $60 filing fee and mail to:

The United States Tax Court

400 Second Street, NW

Washington, DC 20217

Owing Taxes

All right, you’ve exhausted all logical ways to reduce your audit assessment. Or you filed a tax return and owe money. How do you go about paying it?

Naturally, if you have the money, send the check and get it over with. If you’re not liquid right now, here are some ways to pay.

Credit Card

The first two companies listed below have contracts with the IRS and other government agencies. They have been processing millions of dollars’ worth of government credit card payments for about a decade. (The EFTPS program is part of the IRS.) There are two advantages to using credit cards. The first is that you will have immediate proof of payment. The second is the bonus or mileage points you earn for those charges.

• http://www.OfficialPayments.com. Pay IRS, state, and local taxes online and pay a “convenience fee.”

• http://www.pay1040.com. Make federal tax payments online and pay a “convenience fee.”

• https://www.eftps.gov/eftps/. Pay quarterly estimates, payroll taxes, and business taxes online. Money comes directly from your bank account. There are no fees. But this can take a week or two to set up (see Chapter 1).

• IRS Direct Pay. https://www.irs.gov/payments/direct-pay. Pay your federal income taxes, estimated taxes, and a few others directly to the IRS from your bank account without any fees. There is no set-up time, just log in and pay on the spot.

When using the first two services, the tax agency doesn’t pay the merchant fees— you do. (Merchant fees are the costs the merchants normally pay for accepting your credit card.) These fees will cost about 2.5 to 5 percent of the taxes you pay. (They’re called “convenience” fees—that’s for the convenience of the tax agency, not you.)

Suppose you’d like to use your credit cards but don’t want to pay online. Here are two other ways to use your credit cards:

• Alternative 1. Use your credit card checks (you get all those things in the mail, daily, right?). Read the fine print. See what the company is going to charge you. See if you can get a no-transaction-fee check. Remember to ask for reduced interest or 0 percent interest on the transaction fee. The good news is, with the economy getting better, I have started to see offers with 0 percent fees, and up to 18 months with 0 percent interest. In particular, look for the lower offers at credit unions. You might also get your mileage or rewards points.

• Alternative 2. Call your credit card company and request a cash advance to be deposited into your bank account. It will take a week to 10 days, so do it now. If you cajole sweetly, you might get it without transaction fees—otherwise, expect to pay 2 to 3 percent of the amount charged. Look for a card that has a ceiling on the fee (like 3 percent up to $50). Beware. Most don’t—so read the fine print carefully. Be sure to request low or 0 percent interest and ask about the mileage or reward points. Note: While these 0 percent rates used to be good for up to 18 months, many of them are now only to 6 to 12 months. You will find the most current 0 percent cards here— http://iTaxMama.com/Credit_Cards.

You Can’t Afford to Pay Now, But Will Ultimately

If this is the case, there are three ways to go.

1. File Form 9465, Installment Agreement Request. This is the method the IRS suggests. Think twice before requesting an installment agreement (IA). There is a $120 fee for an IA, which you will have to pay again and again if you default on the agreement. The fee is only $52 if payments are deducted directly from your bank account. (You may qualify for a $43 fee if your income is low enough.) In addition, you give the IRS your bank account numbers and the right to attach your funds if you’re late or miss a payment. In the past, the IRS levied the bank account immediately when you were late. These days, the kinder, friendlier IRS gives you a chance to make good. Or if your financial circumstances have changed, the IRS is willing to revise your IA. If you default, the IRS will levy. Anyone may get an installment agreement, as long as you’re not in default on another balance.

2. Don’t file the Installment Agreement Request immediately. Send the IRS whatever you can afford with the first balance due letter. Save up and send money every time the IRS sends you a balance due notice. If you expect to have enough money to pay the balance off in about six to nine months, this may be cheaper and less invasive than requesting the IA. You’ll still be paying interest on the penalties and taxes, but the interest is in the 3 to 4 percent range these days—that’s probably less than many credit cards.

3. Borrow the money from family or friends. If they love you and trust you—and you’re really reliable about paying them back—it’s the best option. When you’re a few days late, they won’t be attaching your bank account. If you’re going to flake out on the loan, though, don’t borrow the money in the first place. You will destroy valuable relationships and trust. Most important, do not borrow money from family or friends if they have to borrow the money to give to you. After all, if you flake on them, you won’t just destroy your relationships, you could damage or destroy their credit. There are still other options.

When the Balance Is Too Large to Pay Off

The balance is so large that you’re just never going to have the money. Perhaps, you’re elderly and are living on a fixed income. Or you’re insolvent. You can’t even afford a bankruptcy attorney. You’re not hiding any assets or money. If this is the case, call the IRS and tell the truth. The IRS can put a special collections hold on your balance due for six months or a year and will contact you to review the situation, periodically, for the next 10 years. If, during that time, you can never pay it, you’re off the hook.

There is a 10-year limit for the IRS to collect money from you after a tax debt is recorded. Your state may have different limits or no limits at all (meaning they can collect forever). We usually recommend paying off the state. That debt is generally lower, and easier to afford.

Some actions can stop that 10-year clock, but it’s best if you get a good tax professional to help you determine where you stand when you’re in that situation. I always used to have a tax attorney perform those computations. These days, there’s some pretty nifty software available to tax professionals that can help us get definitive information about your deadlines.

Request an Offer in Compromise

Suppose you aren’t really insolvent, but the balance is just so unbearable that you feel beaten down by it. Perhaps you have a job or some sort of steady income from your business, but you’ll never earn enough to pay all the taxes due.

You do have a way out. The Offer in Compromise (OIC) Program might be able to help you. When you file an offer in compromise, you’re asking the IRS to accept a fraction of what you owe on your taxes—and to write off the rest of your debt. But don’t get carried away. There is no promise that your tax debt of $50,000 will get cut to $3,000—despite all those ads you see on television.

The OIC Myth

Washington—The Internal Revenue Service today issued a consumer alert, advising taxpayers to beware of promoters’ claims that tax debts can be settled for “pennies on the dollar” through the Offer in Compromise Program. Some promoters are inappropriately advising indebted taxpayers to file an Offer in Compromise (OIC) application with the IRS. This bad advice costs taxpayers money and time. An Offer in Compromise is an agreement between a taxpayer and the IRS that resolves the taxpayer’s tax debt. The IRS has the authority to settle, or “compromise,” federal tax liabilities by accepting less than full payment under certain circumstances.11

As it happens, after the IRS issued that bulletin in 2004, it shut down several national companies that had been ripping off taxpayers.

Qualifying for an Offer in Compromise

Late-night television, radio, and even some daytime television commercials fill your ears with promises of tax miracles. You’re probably getting lots of e-mails, too. Since the IRS filed a tax lien against you, your mailbox is being filled with solicitations from certain tax firms promising you quick resolution of your problem. Be wary. The truth is most outfits will take far too much of your money—and not help you nearly as much as you’d expect. One promoter even offered a discounted price of $1,500 to give you a do-it-yourself kit, with instructions. That firm was shut down by the IRS, and some members did jail time. Only use firms when you can get a recommendation from someone you know who has used them successfully. Otherwise, go to your own tax professional for help or for a recommendation. If you have no recommendation source, look to smaller, local EAs and CPAs who have experience getting their clients offers in compromise. They won’t have massive caseloads and will be able to provide personal service. The two best places to find some reliable help are:

• NAEA (see Chapter 1)—http://www.eatax.org/. Your best bet is someone whose profile shows that he or she is an NTPI Fellow. That means the person has graduated from all three levels of the National Tax Practice Institute.

• ASTPS (American Society of Tax Problem Solvers)—http://www.astps.org/tax-help/. You will find CPAs, EAs, and attorneys with the CTRS (Certified Tax Resolution Specialist, like me) who have graduated from the ASTPS Boot Camps and annual training, or passed their 11-page, in-depth examination.

Fortunately, I have come to know some of the best people in the country, because I teach the Tax Practice Series and my EA Exam Courses.

The IRS also offers a do-it-yourself kit. It’s free. There’s a Form 656 kit that can be downloaded from the IRS’s website. The IRS even provides workshops on filling in these forms. Check the IRS website at http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_OIC or call the agency at (800) 829-1040 to see if it is offering a workshop near you. But before you do all that, let’s see if you qualify.

What if you don’t qualify for an OIC? Don’t waste your time applying if you don’t meet the IRS standards for applying. Here are some general parameters—not the ones the IRS posts—but the reality it uses when considering your offers:

• Are you young, healthy, and able to work?

• Do you have a college education but are choosing not to pursue work in your own field because you’d rather follow your dream?

• Do you have a steady income?

• Do you have equity in your home? Or an IRA or other retirement account?

• Are you expecting a windfall? An inheritance? Or a great job about to start pouring money your way? Don’t lie. That’s tax fraud. It’s one of the few reasons the IRS will send you to jail.

Look at your own earning capability over the next five years. Even though it may be tight, if there’s enough left over, by living within your means or restructuring your lifestyle, the IRS will reject your offer. It won’t wait while you pursue your dreams and live as a starving artist. It will simply reject your offer in compromise.

Suppose you do qualify and are ready to prepare an OIC. Be thorough. Attach legible copies of all forms, bank statements, and bills requested by the IRS. Enclose three months’ worth. Read the information about how it all works on the IRS website http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_OIC. If you’re not willing to provide the IRS with this much information, don’t even start the process. The IRS now requires a fee of $86 that must be sent in with the application. So you’re wasting your money if you don’t follow through.

The IRS reports that more than 80 percent of applications for offers in compromise are rejected as incomplete. Another 10 percent are rejected because people don’t respond. If you simply attach everything and enclose anything else the IRS wants, you’re already in that small minority that might get accepted.

While I warn you away from unscrupulous representatives, I do recommend that you work with a competent tax professional who has a track record of getting OICs for his or her clients. It is a long, complicated process, and having a pro who has gone through it can help. Since you must provide all the documents anyway, you can save yourself dozens of hours of billable time if you gather them all and organize them yourself. I won’t go into any more detail here; the application packet is remarkably self-explanatory.

But if you want some in-depth training on how to handle your offer yourself, sign up for one or more of my Tax Practice Series classes. The sessions are taught in plain English, and include tricks and tips for the professionals to use for their clients. The whole series costs about the value of a one-hour consultation with a tax professional. See http://www.cpelink.com/teamtaxmama.

The IRS is catching up on to its caseload. The latest news is that offers are being settled in nine months or less. Naturally, the “or less” part is for offers that are presented with complete information. The other good news is, with the Fresh Start Program that the IRS introduced a few years ago, the balances you have to pay to settle the offer are more reasonable than ever. The costs? Even if you hire an ethical tax professional to deal with the IRS on your behalf, expect to pay for at least 10 to 15 hours, if you’re organized and cooperative. If you must be chased down and hounded to get documents or if you just dump all your records on the tax pro you hired and expect him or her to do all the work, you’re up to 20 to 40 hours.

How About Filing Bankruptcy?

Perhaps you don’t want to go through the misery of an OIC. You may not want to subject yourself to remarkable levels of stress and frustration, feeling you’re at the mercy of an arbitrary system. You have one last alternative.

Look into bankruptcy. Discharging tax debt isn’t easy. When you qualify, it is faster than an OIC, less intrusive—and much cheaper. Attorneys handling this will typically charge about $3,000.

To discharge your taxes in bankruptcy, you must qualify.

• All your returns have been filed.

• If filed, the taxes due were not based on fraud.

• If filed late, the return was filed two years or more before the bankruptcy petition.

• The tax return, with extensions, was due three years or more before filing of the bankruptcy petition.

• Tax liability was assessed more than 240 days before filing of the petition.

All of those requirements must be met in order to qualify.

There are several complications about how the 240 days are counted or what stops the clock. As with all benefits, this one won’t come too easily.

The biggest hurdle for many to overcome is the emotional one. There is an intense feeling of failure, of self-denigration when you’re reduced to this. But if this is your only—or your best—option, take it. Trust me. I’ve seen the transformation in people who did. Many people spend years trying to resolve their tax debt through the IRS’s channels and simply end up wasting 5 or 10 years feeling worthless, unable to sleep, and unable to maintain their relationships. Yes, taxes do destroy relationships.

Sometimes it’s best to just clean the slate and start fresh. But if you do, make sure you don’t get into trouble again. Please, don’t use tax bankruptcy as part of your regular tax plan.

Summary of IRS Interactions

The information in this one chapter took me more than 20 years to learn—and then another 15 years of constant research, reading, asking, probing, and pressing IRS managers and executives. Thank goodness, they have been remarkably patient with me. I also have the privilege of consulting some of the top experts in the field. Much of my experience came through sheer stubbornness and the refusal to back down to my fear of the IRS. The rest of the information came through lots of audits and thousands of responses to notices. It helped that in the past few years, we really did get a kinder, gentler IRS.

Using the guidelines in this chapter, you’ll never have to be afraid of the IRS or mystified by its confusing notices. You have everything you need in order to know how to respond to the usual notices—and audits.

Tax Notices, Audits, and Collection Notes Resources

Important Acronyms

• FYTIN—form, year, TIN. What you write on all checks to government agencies.

• KGB—Know, give up, backup. An audit negotiating tool.

IRS Resources

• Main reference page to search for IRS notices and explanations. http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_Notices.

• List of IRS notices and explanations for individuals. http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_CP_Indiv.

• Internal Revenue Manual, Part 4, Examining Process. http://iTaxMama.com/IRM_Part4.

• Internal Revenue Service fast-track mediation process for audits and collections disputes. http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_FastTrack.

• Internal Revenue Service offer-in-compromise information. http://iTaxMama.com/IRS_OIC.

• Form 433-A, Collection Information Statement for Wage Earners and Self-Employed Individuals. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f433a.pdf.

• Form 433-B, Collection Information Statement for Business. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f433b.pdf.

• Form 656, Offer in Compromise Application and Instruction Packet. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f656b.pdf.

• Form 2210, Underpayment of Estimated Taxes. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f2210.pdf.

• Form 8822, Change of Address. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f8822.pdf.

• IRC §7491, Shifting the Burden of Proof to the IRS. http://iTaxMama.com/Burden_of_Proof.

Online Credit Card Payment Resources

• IRS Direct Pay. https://www.irs.gov/payments/direct-pay. Pay your federal income taxes, estimated taxes, and a few others directly to the IRS from your bank account without any fees.

• Official Payments. https://www.officialpayments.com/index.jsp. Lets you pay IRS, state, and local taxes online via credit card. There are fees.

• PAY1040.com. https://www.pay1040.com/. Make federal tax payments online via credit card. There are fees.

• EFTPS (Electronic Federal Tax Payment System). http://www.eftps.gov. Pay quarterly estimates, payroll taxes, and business taxes online.

General Bankruptcy and Tax Bankruptcy Resources

• TaxMama. http://taxmama.com/tax-bankruptcy/bankruptcy-freedom.

• U.S. Tax Court. http://www.ustaxcourt.gov/forms/Petition_Kit.pdf. U.S. Tax Court Small Case Petition Kit.

Credit Resources

• Best Credit Card rates. http://iTaxMama.com/Credit_Cards.

• Ilyce Glink—credit and finance books. http://www.thinkglink.com.

• Liz Weston—credit guidance and resources. http://asklizweston.com.

Tax Information Resources

• Kelly Phillips Erb, aka TaxGirl. Excellent tax articles at Forbes.com. http://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb.

• MarketWatch Tax Watch. Eva Rosenberg’s tax articles—http://www.marketwatch.com/topics/journalists/eva-rosenberg.

• TaxMama’s Courses on Resolving Tax Issues. http://www.cpelink.com/teamtaxmama.

• TaxMama’s Course to become an Enrolled Agent. http://irsexams.school/.

• TaxMama’s Quick Look-Ups. http://iTaxMama.com/TM_QuickLookUp. You will find all kinds of useful reference materials, webinars you can replay, e-books, and more.

• Your Business Bible. http://www.yourbusinessbible.com. Look for worksheets, printable checklists, and other goodies and resources.

1 IRS Statistical Reports—Table 10. Examination Coverage: Recommended and Average Recommended Additional Tax after Examination, by Size and Type of Return, Fiscal 2002, available at http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/02db10ex.xls.

2 Table 9b. Examination Coverage: Individual Income Tax Returns Examined, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Fiscal Year 2014 (https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/14db09bex.xls).

3 Love gossip? For more stars in tax trouble, see Kay Bell’s blog http://www.dontmesswithtaxes.com/celebrity/ http://www.dontmesswithtaxes.com/celebrity/.

4 Los Angeles reporter Stan Chambers of television station KTLA writes about the Rodney King and Watts riots, available at http://www.emmytvlegends.org/interviews/people/stan-chambers.

5 IRC §162, available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/162.

6 Cohan v. Commissioner, 39 F.2d 540 (1930).

7 Internal Revenue Manual, Part 4, Chapter 13, “Audit Reconsideration”—Read the IRS’s internal instructions, available at https://www.irs.gov/irm/part4/index.html.

8 http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/windsor-v-united-states-2/.

9 https://www.irs.gov/PUP/individuals/factsheet.pdf.

10 http://taxcourtexam.com/exam-faqs/.

11 IRS Notice 2004-17, dated February 3, 2004, available at https://www.irs.gov/uac/check-carefully-before-applying-for-offers-in-compromise.