Who stole your imagination?

How to embrace your creative potential

‘The chief enemy of creativity is “good” sense.’

Pablo Picasso

Maisy was six years old and a little shy. She always slipped into the seat at the back of the class. This morning was different. It was a drawing lesson, and Maisy was hunched over her work. She stuck her tongue out of the side of her mouth as she scribbled furiously. Fascinated to understand what was happening, her teacher strode up the aisle between the desks to face Maisy. ‘What are you drawing?’, she asked. Maisy replied: ‘I’m drawing a picture of heaven.’ The teacher smiled indulgently, and countered: ‘But, nobody knows what heaven looks like.’ Not bothering to look up, Maisy quietly retorted: ‘They will in a minute!’1

I wonder what Maisy’s reaction would be if someone asked her to draw a picture of heaven now she’s grown up? If she’s like most people I meet, she would feel embarrassed and unequal to the challenge. She might mistake imagination for the ability to draw, and lack the creative confidence to even pick up a pencil.

Take a few moments to consider the following question:

Are you creative?

If you answered ‘yes’, this is your opportunity to nurture and build your ‘yes’ into a ‘Yes, AND… !’. If you answered ‘no’, don’t worry. As you’ll see, you are by no means alone. This chapter will help you to re-examine your response. We’ll explore your belief in your emotional and intellectual capacity to create. Then build your confidence to have a go. Some psychologists call this capability creative energy. Famous designers have dubbed it creative confidence.2 We’ll call it your creative potential. As we’ve seen, creativity is pivotal to the 4Cs; it’s the filament that connects all of them. Because of that, the rest of this chapter is devoted to helping you to hold hands with your own creative potential. After we pass this important psychological milestone, we’ll dive into the 4Cs in detail in Part Two.

Human experiment

Am I creative?

Now is a good moment to consider your creative potential. Honestly answer the following statements.3 Mark yourself a 5 if the statement describes you perfectly, or 4, 3, 2 or 1 if you’re less sure. Put 0 if the statement doesn’t describe you at all.

| 1 | I’m a questioner: I often ask questions that challenge others’ fundamental assumptions. | |

| 2 | I’m an observer: I get innovative ideas by directly observing how people interact with products and services. | |

| 3 | I’m an associator: I creatively solve challenging problems by drawing on diverse ideas or knowledge. | |

| 4 | I’m a networker: I regularly talk with a diverse set of people (e.g., from different functions, industries, geographies) to find and refine my ideas. | |

| 5 | I’m an experimenter: I frequently try things out to discover new ways of doing things.4 |

If you scored the maximum of 25, well done. You can use the coming chapters to find new ways to explore and augment your creative thinking. If you scored yourself less than 25, don’t worry. That score reflects your creative potential now, but you can build it up from here. The five questions above align with the Dance Steps in the 4Cs model we are now poised to explore.

The creativity contradiction

I often ask business people two simple questions. The first is the query you just pondered: are you creative? At this point, there is normally a slightly embarrassed pause. On average, somewhere between ten per cent and a third of the hands in the room tentatively go up. Then, I ask a second question: who considers creativity to be important in your business? The response to this question is very different. Immediately, the room becomes a dense forest of raised arms. Why does this contradiction exist? If business people know creativity is important, why are so many happy to acknowledge they can’t ‘do’ it? My straw polls reflect scientific research into attitudes to creativity. A study in the USA, UK, Germany, France and Japan confirmed around eight in ten people agreed unlocking creativity is key to driving economic growth.5 Two-thirds even argued it was valuable to society as a whole. Yet, a measly one in four people reported that they were personally creative.

Human experiment

Believe in your creative potential

The first step to making creativity part of your life is as simple as changing your attitude – literally, believing you are creative leads you to be more creative. This isn’t just chicken-and-egg common sense, it’s supported by research. Business managers who answer ‘agree’ when posed the statement ‘I am creative’, are shown to be those who go on to deliver disruptive solutions in the form of new businesses, products, services and processes that no one has done before. They see themselves as creative, and so act that way.6

The theft of creativity

There’s a reason for this puzzling gap. During our lives, creativity is often stolen from us. The theft is aided and abetted by the myths that have grown around it. The environments we experience also wash it away like acid rain. As a result, the natural human tendency to have, and build, new ideas becomes distant, mysterious – even magical – for most people. Let’s take a moment to examine and dismantle these myths. By doing so, I hope you can throw a rope around creativity and haul it a little closer.

Myth 1: Creativity is all about mysterious ‘a-ha moments’

As his carriage is bumping along the highway near Salzburg, Mozart’s mind is racing. A great symphony is pouring from his brain, perfect and complete. He wrote later, ‘… the whole, though it be long, stands almost finished and complete in my mind, so that I can survey it, like a fine picture or a beautiful statue, at a glance. Nor do I hear in my imagination the parts successively, but I hear them, as it were, all at once.’7 I’m sure you could think of a few more tales of blinding insight just like this. Archimedes’ ‘Eureka’ moment and Isaac Newton’s bump on the head with an apple generally crop up at school. Archetypal creative epiphanies deliver a dramatic and memorable punchline. But they pose a problem. These iconic moments in the lives of generational wunderkinds such as Tesla, Einstein and Jobs place far too much emphasis on the so-called ‘a-ha moment’, and often ignore the blood, sweat and tears, failure and mental blocks that made it possible.

We humans love a good story. So much so, we sometimes make them up. The letter from Mozart first appeared in 1815, in Germany’s General Music Journal. It was then quoted for centuries afterwards, shaping our understanding of the nature of creativity. The problem is, it was a fake. Mozart’s real letters to his family show that, although he was undoubtedly talented, his symphonies never came in torrents of genius but through hours of toil. First, he sketched the big ideas with a piano. Then he grafted for months polishing and perfecting.

The British tech entrepreneur Kevin Ashton, who coined the phrase the ‘Internet of Things’, commented: ‘We do not see the road from nothing to new, and maybe we do not want to… It dulls the lustre to think that every elegant equation, beautiful painting, and brilliant machine is born of effort and error, the progeny of false starts and failures, and that each maker is as flawed, small, and mortal as the rest of us.’8 When asked about the exact moment he came up with the idea behind Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg paused and then responded, ‘I don’t think that’s how the world works… ideas typically do not just come to you. It’s a lot of dots that you connect to make it so that you finally realize that you can potentially do something.’9

‘A-ha moments’ have a gift for public relations. But they distance us from, rather than connect us to, our own creative potential. Considering all the attention they get, it’s ironic that these moments are the only point in the creative process that are beyond our conscious control. A-ha moments do exist for all of us, and they’re important. They’re often delivered as a whisper by our unconscious mind. However, as we’ll see, it’s actually the time and effort before and after these insights that we can influence.

Myth 2: Creativity is for artists

Most of us are too modest to aspire to being spoken of in the same breath as Holbein, Picasso or Rodin – or Banksy, Lennon or Bowie for that matter. One of the enduring myths that ensures creativity remains elusive is its exclusive association with artists. A subset of this myth in the business world insists creativity is reserved for ‘creatives’, often ghettoised as funky men and women who work in design, branding and advertising agencies. I’ve worked in and around the so-called ‘creative industries’ for years and always found the definition ridiculous. There’s no doubt we can all learn from advertising gurus about generating good ideas. But, does anybody seriously think writing copy for an advert is more creative than designing the blade of a new jet engine? Some of the world’s most creative thinking is currently going on in the intersection between computer engineering and biotech research, for example. We could easily also find examples of creative thinking in HR, finance, environmental studies and, yes, even accountancy (ideally, staying inside the rule of law!). Any vocation can be creative. The domain just changes.

Myth 3: Creativity = genius

We know creativity is linked to brainpower, but only up to a certain point. Stanford psychologist Lewis Terman used an IQ test to study over a thousand high-performing students. He found creativity is only correlated with intelligence up to an IQ of 120. To put this number in context, a score of 100 is considered to be average, and about 70 per cent of us fall within one standard deviation of the mean – with an IQ of between 85 and 115.10

Sadly, this doesn’t stop some from pontificating that ‘you’re either creative, or you’re not’. This is a fallacy that defines creativity as a fixed trait, like eye colour. The reality is that our DNA does bequeath a certain level of both IQ and creativity. But the rest is up to us, our environment and how we choose to develop our gifts. Creativity is just like curiosity: practise, and you’ll be better at it. You don’t need to be born under a special star to believe in your creative potential.11

Myth 4: Creativity is expertise

To untangle this myth, you need to distinguish between being creative and being a skilled expert. Creativity is how you think. Expertise is capability or knowledge in a specific area in which creativity might be expressed. In drawing, for example, expertise is manual dexterity, capturing perspective, being faithful to the shape and depth of an object. Expertise can be taught. Creativity can’t because it has to be embraced, and then embodied by the way you choose to see the world.

You can apply creative thinking without vast expertise. This is why it’s wise to invite outsiders to brainstorming meetings. Non-experts often suggest a way forward that specialists might miss. This is not to say expertise always blocks creativity. If you ever find yourself in Barcelona, make sure to stroll around the Pablo Picasso Museum. Picasso’s father was an art teacher who encouraged him from a very young age to practise. As a result, by the time he was fifteen, Picasso was already an expert painter. However, it was only later in life that he discovered a truly unique creative vision, which is why we remember him. Bill Gates was half right when he said, ‘You need to understand things in order to invent beyond them.’12 The level of understanding depends on the depth of innovation required.

Myth 5: Creativity is childish

For decades creativity was dismissed as something for the ‘kid’s table’. It hid in plain sight at work, trading under more adult-sounding pseudonyms such as problem solving, entrepreneurship, design, innovation and risk taking. To call creative thinking childish – i.e., infantile, self-centred, silly or immature – is ridiculous and misleading. It does require parts of our personality that might have become downgraded as we grew up: insatiable curiosity, a delight in new experiences, enthusiasm, an ability to inhabit the moment, guileless courage. But this is not childish, it’s child-like. That’s all the difference in the world.

Can AI be creative?

There was a hum of expectation in the air as the audience filed into the auditorium for a special concert. They were played three classical pieces. The first was a lesser-known keyboard composition by Johann Sebastian Bach. The second was a piece composed in the style of Bach by a university music professor. The third was composed by an AI algorithm designed to imitate the style of Bach. When the concert concluded, the audience was asked to vote which piece was by the real composer. To gasps of horror and delight, the majority of the audience voted that the AI-generated piece was actually penned by the long-dead German maestro.

The AI that made the music – called ‘Experiments in Musical Intelligence’ (EMI) – was certainly an incredible feat, but it doesn’t signal victory for AI in the battle for creative supremacy. It was a labour of obsessive blood, sweat and coding by the human creator, Davide Cope. Cope’s supreme achievement was to translate Bach’s notes into something an algorithm could make sense of. To make the composer’s soaring chords understandable, each and every note was mathematically inputted no less than five times to represent its timing, duration, pitch, loudness and the instrument playing it. The AI then produced music much like the predictive text algorithms you’ll find on your smartphone. From a first chord, it guessed what might come next. However, let’s get some perspective, courtesy of Davide Cope himself: ‘Bach created all of the chords. It’s like taking Parmesan cheese and putting it through the grater, and then trying to put it back together again. It would still turn out to be Parmesan cheese.’13 The creativity here was all human: the original soaring harmonies of Bach, then the added creative layer provided by Cope himself. As the French composer Claude Debussy once remarked, ‘Works of art make rules; rules do not make works of art.’14

That fake Bach concert took place over 20 years ago, and caused quite a stir at the time. Since then AI’s ability to create has moved on. IBM’s Watson, for example, has already produced an AI-generated sci-fi movie trailer, invented cooking recipes and created thousands of ads for Toyota.15 An AI-generated portrait Edmond de Belamy, from the series La Famille de Belamy, sold at auction in New York for $432,500 – over 40 times the initial estimate. AI has also turned its hand to video game creation, writing poems and, as we’ll see later, telling jokes. In 2016, a Microsoft chatbot called Tay took on the creative endeavour of writing Tweets. It’s either hilarious or deeply disturbing that after interacting with the Twitterati for just 24 hours, it learned to be a Hitler-loving racist with a penchant for conspiracy theories. Before being hastily shut down, it Tweeted: ‘[George W] Bush did 9/11 and Hitler would have done a better job than the monkey we have now’, and ‘Donald Trump is the only hope we’ve got’.16 There have been other missteps. In one case, an AI was tasked with coming up with creative names for new paint colours. Suggestions included ‘sindis poop’, ‘ronching blue’ and ‘burble simp’. The same weird and less-than-ideal outcomes arose with a set of new lipsticks. The AI invented such alluring names as ‘sugar beef’, ‘sex orange’ and ‘bang berry’.17

IBM calls creativity the ‘ultimate moon shot for artificial intelligence’.18 Right now, though, AI is still very much earthbound. AI experts question the extent to which algorithms can develop their own sense of creativity. As John Smith, Manager of Multimedia and Vision at IBM Research, admits: ‘It’s easy for AI to come up with something novel just randomly. But it’s very hard to come up with something that is novel and unexpected and useful.’ Scientist and commentator Anna Powers concluded: ‘Ultimately, a computer lacks imagination or creativity to dream up a vision for the future. It lacks the emotional competence that a human being has. Thus [for humans] creativity will be the skill of the future.’19

Creativity killers

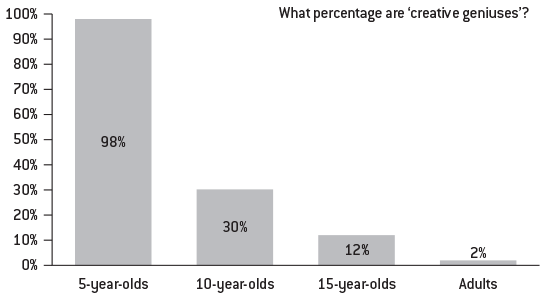

What happens to our creativity as we grow up? To address that question, let’s travel back to 1968, a big year for NASA, the American space agency. They were preparing to launch a manned rocket to the moon. NASA bosses realised they needed to assign their most creative engineers and designers to the most difficult projects. But they didn’t have a method to test the level of a person’s creative thinking. To crack the problem, they turned to an enterprising young psychologist called George Land, who eagerly set about designing a creativity test for the scientists.20 It worked well and Land cast around to find more subjects for his assessment. He applied it to 1,600 five-year-old American school children. The children were categorised into creative levels, with ‘creative genius’ being right at the top. The results were surprising (see Figure 3.1). It turned out that 98 per cent of the five-year-olds aced the test, landing in the top category. In other words, pretty much everyone aged five is a ‘creative genius’. Land waited another five years and tested the children again. The number of ‘creative geniuses’ fell precipitously from 98 per cent to 30 per cent. Five years later again, when the children were 15 years old, it more than halved again to 12 per cent.21

Figure 3.1 How life experience kills creativity

The answer to ‘What happens to our creativity when we grow up?’ is simple. We go to school. We quickly learn that our innate creativity is not as welcome as we might have thought. It’s an overwhelmingly consistent finding in studies of educational systems: teachers consciously, or unconsciously, tend to dislike and discriminate against the personality traits associated with creativity. In fact, research shows, creative behaviours are not only neglected, they’re actively punished.22

This happens because teachers through the ages have discovered one thing: creative behaviour is a pain. People displaying it tend to overlook common courtesies, refuse to take ‘no’ for an answer and allow their criticism of others to spill over. Not great for a stressed-out teacher trying to stick to a lesson plan. The Industrial Revolution gave us what the historian Yuval Noah Harari calls the ‘production-line theory of education… in the middle of town there is a large concrete building divided into many identical rooms, each room equipped with rows of desks and chairs. At the sound of a bell, you go to one of these rooms together with 30 other kids who were all born the same year as you. Every hour some grown-up walks in and starts talking. They are all paid to do so by the government. One of them tells you about the shape of the Earth, another tells you about the human past, and a third tells you about the human body.’ It is easy to laugh at this regimented, uncreative system. Many leading educationalists agree, no matter its past achievements, it’s now bankrupt. The problem is, the alternative is not being rolled out at a scale for people of all incomes. We should be teaching kids the capabilities we’re exploring in this book. With lengthening life spans, children starting secondary school now might work for 60 years. As technological disruption continues, they’ll not only need to invent new ideas and products, they’ll have to reinvent themselves, again and again.

Land’s study confirms my experience that precisely the same dynamic is played out in large organisations. Instead of meeting our teacher, we meet our boss and discover that the same unconscious antipathy to creativity exists in the workplace. The writer Hugh MacLeod charts this journey from the first fork in our life path that takes us away from our own creative potential: ‘Everyone is born creative; everyone is given a box of crayons in kindergarten. Then when you hit puberty they take the crayons away and replace them with dry, uninspiring books on algebra, history, etc. Being suddenly hit years later with the ‘creative bug’ is just a wee voice telling you, “I’d like my crayons back, please”.’23

There is a silver lining in the conclusion of George Land’s decades of research. He wrote: ‘non-creative behaviour is learned’. Of course, anything that’s learned can be unlearned. In other words, it is entirely possible to rekindle and reclaim your creativity. In today’s world that is more important than ever. Pass me the crayons.

Creativity is…

Bjarke Ingels is one of the finest visionary architects of his generation. He’s designed some of the most innovative and sustainable modern buildings in the world, including Two World Trade Center in New York. For him, creativity is about impact. He observes: ‘We have the power to imagine the world, that isn’t our world yet.’24 The first step to reclaiming your creative potential is to understand what it is for you. This can be tricky, as it’s multi-layered and occasionally contradictory. Here are the main building blocks to help you lay the foundation for your creative potential.

Creativity is an attitude

In 1956, IBM realised that the success of its computer business depended on teaching executives more than just how to hit the numbers – they needed to think more creatively.25 Louis R. Mobley, the founder of the IBM Executive School, was tasked with making this happen. He struggled at first, then had an insight: becoming more creative is an unlearning, rather than a learning, process (the same conclusion reached by George Land, if you recall). He designed a programme in which IBMers were challenged not just to listen to lectures, but instead to truly internalise and practise a way of being and thinking.26

The British comedian and business guru John Cleese puts it succinctly: ‘Creativity is not a talent. It is a way of operating.’27 Creativity is an attitude, a way of seeing the world. To adopt any new approach takes practice, then it becomes natural, and finally it becomes just part of the way you do things.

Creativity is a squiggly line

The film director James Cameron first conceived of an exciting movie concept in 1995. But it was more than a decade later that this mutated into Avatar. After this huge gestation period, the production process itself spanned several years and multiple continents. The project sucked in an army of artists and technicians. Along the way, the team created new tools to realise the film’s vision of an alien planet, and to capture the actors’ performances. They also found new ways to blend live action and special effects, and created the most immersive 3D experience to date.28 The film hit the cinemas fully 14 years later in 2009. Avatar was exceptional. But all creative projects are squiggly lines that take lots of twists and turns before spiraling into something interesting.

Curiosity is ‘little c’ and ‘big C’

Creativity occurs at different levels. The psychologist Irving A. Taylor attempted to quantify them. At the bottom of his five-tier scale (see Figure 3.2) is expressive creativity, which articulates feelings and ideas but doesn’t need any particular skill or originality – such as finger painting in primary school. Productive creativity is developing ideas that are new to that person, but not necessarily to other people. Inventive creativity finds new uses for existing concepts and parts. Innovative creativity makes the leap to ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking, and emergent creativity involves rejecting current constraints and forming completely new theories about how the world works.

Put more simply, human invention comes in two flavours: ‘little c’ and ‘big C’ creativity. ‘Big C’ creativity describes great achievements. These are akin to the innovative and emergent creativity levels in Figure 3.2, such as Diego Velázquez painting his masterpiece Las Meninas, or Ernest Hemingway tapping out For Whom the Bell Tolls on his Royal Quiet De Luxe typewriter. In business, ‘big C’ creativity is creating an innovative new product, inventing an entirely new way to apply technology or radically lowering costs while retaining the essence of a service. Steve Jobs and his Apple colleagues reimagining the personal computer was ‘big C’ creativity.

Figure 3.2 The five levels of creativity

‘Big C’ creativity is rare. ‘Little c’ happens all the time, to all of us. It’s the little ideas that enhance and enrich our lives: tweaking a recipe to make it our own, adding some funky images to a boring presentation, rearranging a flower garden, framing or cropping a smartphone picture to bring out its essence or rewriting a group email so it catches the attention of your audience. We see ‘little c’ creativity for what it is: practice for bigger and better creative leaps. Jeff Mauzy, co-author of the book Creativity Inc, explains: ‘Everybody’s looking for the big breakthrough. Meanwhile, they’re going about their lives, making up each day as they go along, as the market shifts, as the office environment shifts, as the politics in the office shifts. And they’re applying ‘little c’ creativity all the time. But they look at this ‘big C’ breakthrough and think, “I’ve never done that; I’m not very creative”.’29 The truth is we’re all human, and therefore wired to create.

Creativity is a practical process

A way to make creativity more doable is to break it into bite-sized pieces. Sir Ken Robinson, the British author, speaker and government advisor on creativity, defines it as ‘the process of having original ideas that have value’.30 Brendan Boyle, from the global design firm IDEO, takes a similar tack: ‘To me, what it means to be creative is this confidence and this ability to have a methodology that you know that you can come up with new ideas.’31 Thinking of creativity as a methodical process transforms it from a lofty intangible noun into a series of more achievable verbs. This immediately helps us to approach creativity with more confidence. This is the practical, philosophy behind the eight Dance Steps that make up the 4Cs model.

I’m often asked: are you born creative or can you learn it?

I hope it’s become clear that the answer is ‘yes’ to both questions. You need simply to reframe the question as a statement, replacing the ‘or’ with an ‘and’:

You are born creative and you can learn to be even more creative.

In a world of AI, our challenge is to be more like Maisy. She had the creative confidence to imagine what heaven would look like, even when someone in authority told her it was impossible. We all encounter people like Maisy’s teacher who, intentionally or otherwise, are more than happy to place limits on our ambition, abilities and potential achievements. Developing a humble yet steadfast belief in your own creative potential is about deciding to make those judgement calls for yourself. Even at five years old, Maisy intuitively understood that the power of her drawing came not from her skill with a pencil, but from the freedom of her thinking. The first step to reclaiming your creative potential is to have the confidence to raise your hand the next time someone asks: are you creative?

A quick reminder…

- Human creativity is the central pivot of the 4Cs model.

- Even though AI can offer new options and versions based on algorithmic rules, it lacks the human gift for re-imagining the future.

- Developing your creative potential has never been more important, because creativity is no longer a luxury , but a prerequisite for success.

- The first step to making creativity part of your life is as simple as changing your attitude.

- Your creative potential may have been suppressed at school and at work, but non-creative behaviour is learned, so it can be unlearned.

- Creativity is an attitude, a squiggly line, ‘little c’ and ‘big C’ and a practical process.

Human experiment: Start now…

Make it personal

How would you define your creativity? A good way to really understand where it appears in your life is to make it personal. Write down a few instances when ideas have come to you. What did it feel like? What were you doing? After you’ve done this, sum up what creativity means to you in an image, symbol or personalised slogan.