Think big, start small, learn fast

Why you need to constantly experiment to test your ideas to destruction – or greatness

‘Life is trying things to see if they work.’

Ray Bradbury, author

Superpower: Collaboration

Dance Step: EXPERIMENT

Igniting questions:

- What should I do when I don’t know what works?

- How do I test my ideas?

- Which ideas do I choose to pursue?

4Cs value: What works, what doesn’t?

We all know it was Thomas Edison who invented the light-bulb. But, there’s a small problem with this well-worn myth: it’s not actually true. Many inventors were working on the replacement for gas lighting in the late 1870s. Gas lanterns could only deliver a flickering light source, not to mention the trifling issue of thousands of suffocations, fires and devastating explosions. Twenty-three different light-bulbs were developed before Edison even began. Some were so good they were already being used to light streets and buildings.

The technical challenge was the same for all would-be light-bulb designers: pass a sufficiently powerful electric current through a strand of material to make it glow, but without setting it on fire. The greatest difficulty was coming up with the best substance that could serve as a long-lasting filament. Edison’s team tested thousands of alternatives, including over 6,000 types of plant materials. The commercial question was just as tricky: how could a bulb perform for long enough – and at the right cost? Eventually, Edison discovered the best substance was carbonised cotton thread. It delivered over 13 continuous hours of light. He filed a successful patent on 27 January, 1880.

So you see, Edison didn’t invent the first light-bulb, he invented the best one through highly structured trial and error. Arguably, the light-bulb is not his greatest achievement. Nor are his pioneering advances in electricity, motion pictures, telecommunications, batteries and sound recording. It’s how he did all those things. His most impressive contribution is not his inventions but the procedure that brought them about at his Menlo Park laboratories in New Jersey: a process to manage thousands of small, deliberate experiments. To Edison, a company was first and foremost an ‘experiment factory’. He famously observed: ‘I didn’t fail 1,000 times. The light-bulb was an invention with 1,000 steps.’ Experiments may feel like something for scientists, rather than a technique you can use in real life. Here, we’ll see how the opposite is true. In this chapter, we’ll learn why experimentation is the most appropriate response when the world is unpredictable and the outcomes of your actions are unknowable. Experiments come in handy when you can’t forecast the future.

In CONNECT, we explored how your thinking can be improved through cooperation and feedback. EXPERIMENT is the final Dance Step because, at some point, you’ll need to trial your ideas. Experiments reveal if your concepts are likely to fly, or flop. Crucially, this approach allows you to move forward with the smallest possible risk before staking your reputation, time and money in a more substantial way.

The best lack all conviction

Despite the predictive power of AI, we still don’t know which new-fangled ideas and products will take off and which will crash and burn. When describing the movie business in his memoirs, Hollywood screenwriter William Goldman concluded that ‘nobody knows’ which film will be successful, and which will sink without trace. Creativity researcher Dean Keith Simonton puts it this way: ‘What is especially fascinating is that creative individuals are not apparently capable of improving their success rate with experience or enhanced expertise… creative persons, even the so-called geniuses, cannot ever foresee which of their intellectual or aesthetic creations will win acclaim.’1 In other words, even the most gifted people have no idea which of their ideas are any good. Experiments help because it’s impossible to predict the strength and validity of many ideas before you test them.

Forecasting is very difficult. However, even when it’s obvious that humans can’t envisage the future, we like to think we can. Experimentation pierces this bubble of fake certainty we tend to inhabit. Our tendency for self-deception was demonstrated in a two-decade study by psychologist Philip Tetlock. In 1984, as the most junior member of the National Academy of the Sciences, he was charged with working out what President Reagan’s response should be to the Soviet Union’s strategic moves in the Cold War. He studied what the experts prophesied and was struck by a common factor: they all disagreed. He went on to analyse nearly 300 authorities on political and economic trends. He asked them to make predictions on what might happen, then patiently waited to see if their guesses came true. He discovered that specialists, as you might expect, did better than a control sample of undergraduates with no expertise. However, he revealed deep expertise didn’t translate into anything close to perfect forecasting. In fact, in one striking example, experts on Canada turned out to be better at predicting events in Russia than the real ‘experts’ on Russia.2

Arguably, the future is now less foreseeable than it’s ever been. We constantly seem to experience astonishing outcomes in technology, business and politics. For example, the vast majority of our financial authorities did not see the devastating credit crunch coming in 2008. Eight years later, in 2016, the UK’s vote to exit the European Union was similarly unheralded by most veteran political pundits. In the same year, experienced pollsters failed to foretell the victory of Donald Trump in the US presidential elections. Despite this, many people still prefer to reside in a self-filtered bubble of bogus certainty. They sustain a misguided faith in their ability to foresee what’s coming. The British poet W.B. Yeats hit the nail on the head when he elegantly described this tendency in his poem The Second Coming: ‘The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.’ Those who lack this conviction prefer to experiment, as it can reveal what works in reality.

Think big, start small, learn fast

Experimentation is action-based. The objective is to verify your assumptions about an assumed idea or fact to make a ‘go! or ‘no-go!’ decision on your creative project. The art is to burn up the smallest possible amount of time, money and effort to learn the most about what works – and what doesn’t. As the French philosopher Denis Diderot wrote: ‘There are three principal means of acquiring knowledge… observation of nature, reflection, and experimentation. Observation collects facts; reflection combines them; experimentation verifies the result of that combination.’

Similar to curiosity and creativity, experimentation is a philosophy on the world. This method of decision making is summed up by the slogan: ‘Think Big, Start Small, Learn Fast!’. Experiments amend the old saying: ‘Always look before you leap!’ They replace it with: ‘Take a small hop, then carefully observe what happens.’ They might suggest bubbling test tubes, unexpected explosions and blackened faces. However, if designed correctly, they shouldn’t be perilous. They’re all about reducing overall risk to its lowest possible level. In essence, an experiment is an attempt to map the fastest route to the truth – the path that offers the least risk of metaphorically falling off a cliff, with the best view of the subject you’re interested in.

By experimenting, you demonstrate a willingness to acknowledge your ignorance. The British historian Arnold Toynbee was known for his prodigious output of articles, speeches and presentations. People could not understand how he accomplished so much. When asked, he replied: ‘I learn each day what I need to know to do tomorrow’s work.’3 The Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping advised that when the currents of uncertainty swirl around you, ‘cross the river by feeling the stones’ under your feet. The Silicon Valley entrepreneur Eric Ries neatly summed it up in his book The Lean Startup when he defined experiments as a tool for ‘validated learning’. Experiments allow you to stay grounded and grope your way forward, bit by bit.4 To know just enough to take the next step. It requires courage to admit you don’t know how things will work out. Perhaps this is why experimentation has not yet been widely utilised by business managers, who are often keen to pretend they’ve got all the answers. As the Nobel Prize winning Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger admitted: ‘In an honest search for knowledge, you quite often have to abide by ignorance for an indefinite period.’5

Human experiment

Write your own press release

Experiments don’t need to be complicated. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos encourages staff to validate their ideas by simply writing a press release. The release is composed for the very first internal discussion of the potential product, rather than just prior to the product’s launch. The goal is to see the new idea through the eyes of a customer before months of expensive development and marketing activity consume cash.

Take a few minutes to write a half-page press release on your favourite value-adding idea. This disciplined approach helps to: 1. clarify your thinking; 2. quickly articulate how your idea benefits others; and 3. place you firmly in the shoes of a potential product user.

Planning versus improvising

Imagine two friends arranging to have lunch. If they were both born before 1980 they’re ‘digital immigrants’. 1980 is the approximate year when computers became ubiquitous. Anyone born prior to this has acquired their limited digital competence during their lifetime, like learning a foreign language. These friends would most probably plan the time, place and date of their lunch beforehand via text message or phone. However, if it was a person born after 1980, she is more likely to be a ‘digital native’. She can’t remember a time without computers in her life. As far as she’s concerned, she probably had an Internet-enabled screen in her crib. She is far more likely to go about organising her lunch in a very different way. First, she’d feel hunger pangs. Then, find the nearest restaurant using the location services on her smartphone. Finally, she’d announce her position via social media to see which of her friends might be able to eat with her. Younger people don’t plan, they naturally improvise.6 As my insightful colleague and generational researcher Tammy Erickson likes to joke: ‘If you plan, you’re probably old!’

Experimentation is a close cousin to improvisation. It certainly resides at the other end of the certainty spectrum to planning. Planning is useful for projects with a fixed outcome, such as arranging lunch at a specific time and place – or launching a rocket to the moon. You locate the moon and then work out how to get there with a detailed plan of action. Life used to be a little more amenable to planning. When I was a strategy consultant in the early part of this century, we forecast on a three-to-five-year time horizon. It’s a measure of how rapidly times have changed that this now seems faintly ludicrous.

Experimentation is not like a mission to the moon. It’s more like driving a car. You know the road you’re currently on and the direction you’re travelling. Experiments are the constant, ongoing feedback loop between the edge of the road and the small alterations you make to the steering wheel to stay on course.7 Experiments rely on what we can observe right now, not at some imagined point in the future. In a fast-changing world, experimentation is essential because it makes more sense to try things and see how they turn out, rather than plan far into an uncertain future.

When to experiment

Experiments are not advisable in all walks of life. Imagine if you were just going under anaesthetic on an operating table. Your heart surgeon leans in, just as you’re drifting off, and excitedly informs you of the fascinating, but risky, procedure he’s going to try out on your internal organs. You might have the same alarmed reaction if a firefighter arrived at your burning home with a novel approach to dousing the flames. Experiments are best applied to new products, inventions and untested ideas, when the risk of failure can be mitigated. Not on the night shift at a nuclear plant.

This still leaves huge expanses of our lives where experiments can add value. The American aviators Orville and Wilbur Wright took five sets of parts with them each day they tested their pioneering flying machine. They would fly, crash, work out what happened, use the spare parts and take off again.8 In 1928, Robert E. Wood, the CEO of US department retailer Sears, opened two competing stores in Chicago. Asked why, he said it was to make sure he picked the right location – and the right store manager.9 In the 1960s, two brothers Dick and Mac McDonald were figuring out the best design for a ground-breaking assembly line for a kitchen called the Speedee Service System.10 Being entrepreneurs, they didn’t go to the expense of building the restaurant itself. Instead they repeatedly designed and redesigned different configurations of burger flipping stations, fryers and mayonnaise dispensers on a local tennis court with a humble piece of chalk. To test the system’s interaction with kitchen workers, they persuaded some local boys to pantomime cooking burgers and fries for an afternoon.11 From this humble experiment the global fast-food franchise McDonald’s was born.

One of the reasons Rich Fairbank targeted the loan and credit card industry in 1988 was because it was an obvious opportunity for interesting experiments. He co-founded the credit card business Capital One because it allowed him to: ‘… turn a business into a scientific laboratory where every decision about product design, marketing, channels of communication, credit lines, customer selection, collection policies and cross-selling decisions could be subjected to systematic testing using thousands of experiments’.12 Capital One now conducts 80,000 such tests every year to feed what Fairbank calls his ‘information-based strategy’. It’s propelled the company to become the fifth-largest provider of credit cards in the United States.13 Many of the iconic tech businesses of Silicon Valley have used an experimental philosophy to drive their success. A software ‘beta test’ is simply an up-to-the-minute app that encourages customers to try out new features. Experimentation is one of the reasons the likes of Google, Amazon and Netflix regularly outmanoeuvre their rivals.

Facebook even experiments on its own staff. When management found employees were eating unhealthy portions of free M&MS they unleashed a team of behavioural scientists. The PhDs spent time observing snacking patterns and cross-referenced this with academic papers on food psychology. They hypothesised that if the company kept the M&MS hidden in opaque containers, while prominently displaying healthier options such as dried figs and pistachios, it would lessen the problem. The result: the 2,000 employees in the New York office scoffed 3.1 million fewer calories from M&MS over seven weeks, a decrease of nine vending machine-sized packs for each person.14 Not surprisingly, a number of mainstream global corporates are now embracing experiments in an attempt to develop a more entrepreneurial culture. Over the last five years, at London Business School we’ve worked on business experiments with organisations in oil extraction, automotive, manufacturing, recruitment, chemical production, banking and insurance, to name just a few.

Innovate or die!

Imagine a game we’ll call ‘Innovate or Die!’. The playing area is like a chess board but bigger: a 10 × 10 grid made up of 100 squares in total. This represents 100 ways in which any problem can be solved. You have 10 chips to bet on the 100 squares. The winning square is decided by a roulette wheel with 100 different slots. This game is a perfect means to understand the difference between a planning and an experimental approach.

In traditional planning mode you choose what you think is your best option from the 100 squares based on analysis, past experience and informed guesswork. I call this ‘decision making by clairvoyance’. You place all 10 of your chips on this single square and cross your fingers you’ve got it right. You put all your eggs in one basket. If you’re correct, this is a perfect approach. It’s both fast and effective, and has huge and immediate payback for your remarkable prescience. If you’re wrong, it’s enormously costly.

In experimental mode your approach is quite different. You cheerfully admit you don’t know which of the squares is the winner. The only logical way to proceed is to split your chips into the smallest possible increments: one chip per square. You place your first chip on one of the squares to see if it wins. Of course, the process takes a little longer, as it will take you 10 turns to test 10 squares in this methodical fashion. It’s slower, but the upside is you’re learning what works and what doesn’t at a far cheaper rate. In this experimental approach you have redefined failure. You have not avoided it, nor have you made it attractive. You’ve simply made it survivable. In experimental mode, failure comes in two flavours: either spending too much time getting to the solution, or trying too few squares and then giving up before you know the winner.

To translate our imaginary game back into real life, think of the single-chip approach as your MVE – the minimum viable experiment, which can test the validity of your latest idea. The ‘4Ss’ of this MVE approach are easy to remember: the smallest, speediest, simplest and safest route to greater learning.15 The only way experiments can fail is if the cost of failure outweighs the value of what you’ve learned. Buckminster Fuller, the innovative architect who invented the geodesic dome, neatly summed it up: ‘There is no such thing as a failed experiment, only experiments with unexpected outcomes.’ So, the only route to disaster is to badly design your experiment. We’ll now find out how to avoid that misfortune.

Human experiment

Design a minimum viable experiment

Think of an idea in your life you’d like to test with the least possible time, effort and risk. Use the ‘4Ss’ (small, speedy, simple and safe) to dream up a trial in the form of an MVE.

Keep it simple

Experiments are trial and error with a structured plan.16 It’s best to keep them as simple as you can. They can be as unassuming as making a rudimentary prototype, mock up, or dummy version of what you’re considering. When Capital One marketeers are trying to figure out which version of an email, font or brand colour works best to illicit a response from their customers, they employ tiny experiments called ‘A/B tests’.17 The marketing team send out two versions of the same email and work out which one gets the biggest response rate. In the software industry, entrepreneurial teams sometimes don’t make a product at all – they merely write a description of the benefits of the product and offer an invitation to try it out. It’s one baby step before the Amazon press release approach I described earlier. The software designers then monitor how many people click on the link to leave their name as a potential buyer of the product.

Human experiment

Make a quick prototype

‘Thinkering’ is a combination of thinking and tinkering. It’s a memorable verb coined by the writer Michael Ondaatje in his novel The English Patient. How might you start ‘thinkering’ to develop a tangible prototype for one of your ideas? This is the decisive, action-based step IDEO designers call ‘getting out of your head’. In some ways, it’s what differentiates our thinking style from AI: we have amazingly dexterous hands that help us to think more physically.

You might make a cheap and cheerful protype out of what is to hand: cardboard, tape, foam, LEGO, kitchen-roll tubes. Fast prototyping is often used in design thinking to quickly test the pros and cons of a product. It doesn’t have to be a physical 3D object. You might simply sketch the solution to make it more real for you and your collaborators. When thinking through a less-tangible service product, I‘ve witnessed business people roleplay the interaction between themselves and a potential customer. In doing so, they’ve ironed out all sorts of glitches – and stumbled on opportunities – along the way. A quick demo is always more convincing than a theoretical business plan.

Exciting problems

Earlier you were encouraged to find ‘killer questions’ that unveil conundrums, glitches and bugs you’d love to solve. Experimentation closes this curious–creative thinking loop to test solutions to these exciting problems. Chances are you’ve already conducted experiments in your life. You may just not have used the word. Here’s a simple, real-life example from my week. Yesterday, I turned on a light switch in my office and the bulb didn’t work:

| • | Problem: The light won’t come on. | |

| • | Question: Is the light bulb blown? | |

| Idea: Replace the bulb. | ||

| • | Hypothesis: If I replace the bulb, then the light fitting will work as it should do. | |

| • | Experiment: Find a new bulb and screw it in. | |

| • | Proof: Does the bulb light up, or stay dead? | |

| • | Outcomes: | |

| A | The bulb does light up (validates hypothesis). | |

| B | The bulb stays dead (hypothesis is invalid so there must be something else wrong, is it the wiring, the fuse… ?). What’s my next experiment? | |

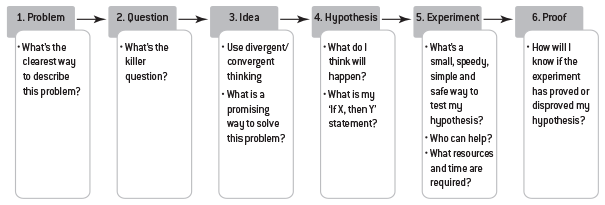

OK, not the hardest problem. And, I’ll admit, my searing insight to replace the bulb is not the idea of the century. But this modest example does clearly explain the experimental thinking process you can apply to almost any situation, as shown in Figure 11.1.

You’ll notice two properties of this experimental process. Firstly, it’s a useful way to validate the consequences of the previous Dance Steps that make up the backbone of this book. The mini-steps here – develop a hypothesis, do an experiment and check the results – drill down into the EXPERIMENT Dance Step to offer a little more structure. Secondly, any robust experiment begins with a well-thought-out hypothesis. In this case, the assumption underlying the hypothesis is that the bulb itself is blown, rather than failing to light because of a power cut, or a loose wire. A good hypothesis is more than a wild guess, but less than a well-established theory. Scientists test a hypothesis in many different ways before it gets labelled as a theory.

Figure 11.1 The experimental process

Human lives are full of unspoken hypotheses. For example, a detective might have a hypothesis about a crime, and a mother might have a hypothesis about who spilled juice on the rug. Here are a few more:

If I fit mudguards on my bike (x), I will get less spray from the road up my back when it’s raining (y).

If a prisoner learns a work skill while in jail (x), then he’s less likely to commit a crime when he’s released (y).

If we introduce homeworking for the HR team(x), then this’ll result in a more productive, flexible and happy workforce (y).

Human experiment

Write a hypothesis

Experimentation is just a method to clearly state your underlying assumptions in order to learn if they are true or false. It’s advisable to use clear, precise language. You’ll notice from the examples above that a hypothesis is always built on a specific sentence format:

‘if we do x, then we think the result will be y’.18

Go back to the MVE you designed earlier. Now, restate the hypothesis at the heart of that potential experiment. You’ll see that the logical language makes it far easier to test the statement with a small experiment.

Throughout The Human Edge I’ve encouraged you to experiment. In this final Dance Step, I’ve simply offered you a more robust way to elevate your explorations to another level. Whether you prefer a more intuitive style of trial and error, or the sort of structured experimentation I’ve described here, one thing’s certain: in a fast-changing world, dumb perseverance is overrated. So is the assumption that you can adequately forecast the future. Small learning steps are far better. Experimentation does not endorse or encourage failure, it simply makes it survivable and useful. Thomas Edison stated: ‘The real measure of success is the number of experiments that can be crowded into 24 hours.’19 Experiments lower the cost of each of your bets. Consequently, if things don’t work out, you’ll have more money left in your bank account for another roll of the dice.

A quick reminder…

- An experimental philosophy is ‘Think Big, Start Small, Learn Fast’.

- Experiments are not advisable in all walks of life, but are well-suited to:

- validating curious and creative thinking;

- the uncertainties of the twenty-first century;

- situations where forecasting has become difficult, and improvising is often the best way forward.

- The art of a well-designed experiment is to spend the smallest amount of time, money and effort in learning the most about what works – and what doesn’t work.

- Experiments make ‘failure’ survivable, and even valuable.

- There are different routes to test a hypothesis, from a simple drawing, a roleplay or a more involved physical prototype – to a full-on collaborative experiment.

- The most effective experiments are simple, small, speedy and safe.

Human experiment: Start now…

Begin a lifetime of experiments

In this chapter you’ve considered the experiments you’d like to conduct, what form they might take and the hypothesis that lies at their heart. Now, try them out. Go ahead and conduct one or more of these experiments.

To help:

- Think about one or more of the ideas you’ve developed while reading this book.

- Apply the experimental approach. Even though it’s written as a linear process, you’ll find you have to go around a thinking circuit a few times to write a hypothesis you are happy with – and to design an experiment that will help you acquire insight.