7 Healthy eating and behaviour change

Geke Ludden and Sander Hermsen

Introduction

Every day, we encounter a broad range of information about what food to eat (‘eat this butter for improved heart functioning’, ‘eat five portions of fruit and vegetables every day’) and about what not to eat (‘drink less sugary drinks’). These messages are supported by a growing body of knowledge about nutrients and their effect on our health. However, despite the increase in available knowledge about our food and how it may influence our health, there is an ongoing rise in lifestyle-related diseases directly associated with our food intake.

Worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975 (WHO, 2017) and the number of people affected by type II diabetes and cardiovascular diseases is rising steadily (Lee et al., 2012). Statistics from countries such as the UK and the US (Bates et al., 2014; Stark Casagrande et al., 2007) tell us that only a small proportion of people meet general dietary recommendations (consuming little saturated fat, added sugars and salt and eating enough fruit and vegetables). Eventually, these unhealthy nutrition patterns will negatively affect the wellbeing of many people and lead to an ever-increasing demand for health care, with an associated increase in cost. Healthy nutrition, therefore, is key to people’s health and vitality. This chapter makes a contribution to Design for Wellbeing that focuses on how to support people in changing their eating behaviour in order to improve their wellbeing.

In recent years, efforts to raise people’s awareness of the importance of living a healthier life as well as to support healthier food intake have widened from traditional information campaigns to monitoring and coaching systems, changes to the public environment and the design of other artefacts for healthy eating (Ludden, 2017; see also Ludden & Hekkert [2014] for a more thorough categorisation). In this chapter, we will explain why many efforts that aim to stimulate healthy eating have limited or even adverse effects on changing people’s eating behaviour. We do so by adopting four views that are relevant to design. For each view, we will discuss relevant literature and the role that design has played and could play when adopting that particular view. Finally, we discuss what bringing the different views together might mean for the future of how to design for healthy eating.

Current efforts to design for healthy eating behaviour

Similar to what Clark (2010) has described as the ‘agency divide’, all efforts to design products and services that support people to adopt healthier eating behaviour can be placed on a continuum with purely informative, non-directive designs targeted at individuals on the one end, and interventions in the public environment that remove all freedom of choice on the other end. We will use this continuum to provide an overview of current design for healthy eating behaviour. A similar categorisation was made for design for behaviour change approaches by Niedderer, Clune & Ludden (2017).

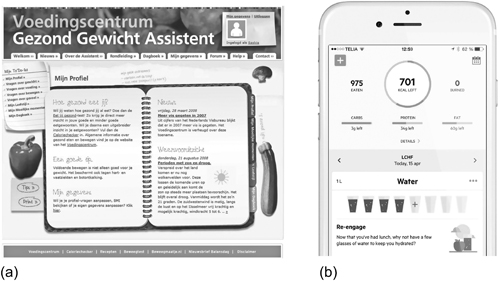

One end of the continuum consists mostly of designs that communicate a norm or try to increase our knowledge. We are probably all familiar with traditional campaigns raising awareness of the importance of eating fruit and vegetables on television, in schools or in the public domain – these include ‘2 Fruit ‘n’ 5 Veg Every Day’ in Australia, see Dixon et al. (1998), and ‘5 a day for Better Health’ in the US, see Kramish Campbell et al. (1999). Valuable initiatives to support people who have decided they want to change their eating behaviour – or at least who want to have better insight in what they are eating on a daily basis – are web-based eating diaries and mobile applications such as the Healthy Weight Assistant and Lifesum (see Figures 7.1a and 7.1b).

Figure 7.1 (a) Healthy Weight Assistant (left); and (b) Lifesum (right).

The Healthy Weight Assistant (Kelders et al., 2011) is an online tool aimed at adults with a healthy weight or who are slightly overweight. It provides users with healthy recipes, provides the opportunity to keep a nutrition diary and supports planning healthy eating goals. An evaluation of this tool (ibid.) shows users were mainly female and highly educated, which is a recurring pattern in eating behaviour interventions: they typically tend to reach only high-socioeconomic status audiences, whereas the problems are more serious among low status groups, at least in industrialised countries (Wang & Lim, 2012). Moreover, adherence to this intervention was as low as 3 per cent; low adherence is another recurring phenomenon in eating behaviour interventions.

The other end of the continuum consists of efforts to influence eating behaviour in the public environment, ranging from healthier (school and business) canteens to attempts at regulating the number of fast-food outlets in inner city areas. Like mass media campaigns, such interventions can potentially reach large groups of people, simply because they can be placed in environments where many people encounter them, but unlike these campaigns, these interventions generally limit the freedom of choice people have. Their potential efficacy is large because, in general, environments influence our behaviour more than our intentions or attitudes (Marteau, 2018). Changing the availability and pricing to promote fruit and salad purchases in cafeterias may be seen as an example of a true environmental intervention. One such intervention (Jefferey et al., 1994) consisted of doubling the number of fruit choices, increasing salad ingredient selection by three and reducing the price of salad and fruit by 50 per cent, with very positive results; both fruit and salad purchases increased markedly. When the interventions were removed, fruit and salad purchases dropped again to remain slightly above baseline. Hanks and colleagues (2012) came up with another example of an environmental intervention, following the strategy of making healthy choices more convenient relative to less healthy choices by arranging one of two lunch lines in a cafeteria as a convenience line that only displayed healthier food and beverage options. They found that as a result of their intervention sales of healthier foods increased and that of unhealthier options decreased.

There have as yet been only a few ‘true’ environmental interventions for healthy eating. Most interventions involve some form of self-management. The ETE-plate by Annet Bruil, for instance, uses coloured lines to provide eaters with guidance of preferred portion sizes for balanced meals. The plate has sections for proteins, vegetables and starch-based food, and is designed to accommodate both European and South-East Asian cuisines. A recent study among hospital staff in Singapore showed that, even after six months, users of the plate ate more vegetables and fewer carbohydrates than a control group who did not use the plate (De Korne et al., 2017). The design of the MindFull plate and bowl (Andereae, 2017, see Figure 7.2) follows a different approach following from the idea that how full we feel depends more on how much we think we have eaten than on the actual amount of food consumed. Mindful exploits errors in sensory perception to influence people into feeling full.

Figure 7.2 The MindFull soup bowl seems bigger than it actually is. This illusion is meant to trick people into feeling fuller than they actually are.

Although diverse and plentiful, many interventions for healthier eating tend to lack effect; a fact that is partly hidden by publication bias: unsuccessful interventions more often than not end up in the proverbial filing drawer (but see, e.g., Dassen et al., 2017, on an ineffective gamified training for overweight individuals, or Lloyd et al., 2018, on a failed lifestyle programme to prevent obesity in UK primary school children). This shows that changing eating behaviour is complex and difficult. In many cases, merely suggesting that we should change our eating behaviour (think of, for example, a school council that suggests to parents that they should prepare healthier food for their children), can cause quite some resistance. One reason for this resistance is the strength of cultural and emotional connotations of eating. Food is connected to social contexts, cultural values and identities that we are reluctant to let go of or change in any way.

The next sections will introduce four views on why the effects of current designed interventions to changing people’s eating behaviour are limited: (1) the knowledge view, (2) the automaticity view, (3) the social/cultural view and (4) the engagement view. From our analysis of how these different views can explain the limited effects of current interventions, we will distil design directions for more effective designs.

(1) The knowledge view: Too much focus on knowledge of healthy eating

The majority of designed artefacts aimed at healthier nutrition consist of designs that inform us about what, when and how much we eat or should eat. This approach seems logical, considering the lack of knowledge some people seem to have about these subjects and the increasing knowledge that is available about how our nutrition affects our health.

Many designers and health professionals therefore consider knowledge to be the key issue for healthy eating and see teaching nutritional facts as the preferred strategy for behavioural change designs. This is most apparent when we look at designs aimed at children, such as the Alien Health Game (Johnson-Glenberg & Hekler, 2013), in which children make food choices. The (correct) healthier choices improve the alertness and health state of an alien avatar. Although the game evidently led to a greater knowledge about healthy nutrition in the participants, this approach has some problematic aspects that illustrate why, generally, an approach aimed at increased knowledge has only limited success.

First, while it seems obvious to start teaching about nutrition at a young age, we should not overestimate how much influence children have over their diets. Parents and – in many cultures – schools and daycare centres determine children’s diets. Adults, too, often have only limited control over their diets. We will address the importance of integrating social systems and environments in interventions for healthy nutrition later in this chapter.

Second, when you attempt to sow knowledge, you are likely to harvest a reaction. Many adolescents, for example, eat unhealthily. At first glance, this seems to be a knowledge problem: adolescents have a low risk perception of (the consequences of) their unhealthy diet (Hermans et al., 2017). But attempting to increase their knowledge will only lead to their rejection of your persuasive attempt. Adolescents feel that others may be in danger, but they certainly are not. Moreover, they are seeking food choice autonomy, and will reject any limitation of that autonomy (ibid.).

This process of attitudinal bolstering does not limit itself to adolescents. Adults are also likely to resist persuasion. Reactance to the persuasion attempt is often accompanied by scepticism about the reliability of the source. When the Netherlands Health Council (2015) published new guidelines for healthy nutrition, they encountered some prime examples of both reactance (‘they are always trying to deny me nice things’) and scepticism (‘this is the food industry talking’).

Third, more often than not, there is no lack of knowledge, even though it seems that way. Often, we do know what is right for us, but we fail to act in an appropriate manner: the famous intention-behaviour gap (Sheeran, 2002). This gap between what we know and how we would want to act on the one hand, and our actual behaviour on the other hand, can be seen in many parts of our eating behaviour. Research shows a gap between knowledge and proliferation of hygiene standards in the kitchen (McCarthy et al., 2007), of knowledge of and adherence to healthy diets at work (Mhurchu, Aston & Jebb, 2010) and of parental intentions when it comes to children’s snacking and their actual behaviour (Larsen et al., 2018).

Even though knowledge is often not the problem, and even though knowledge often leads to reactance, food and eating education can still be successful in some cases. A good example is the Child Feeding Guide, developed by researchers from Loughborough University in the UK (Haycraft, Witcomb & Farrow, 2016). This app and the website provide parents with tips and tools to deal with picky eaters. During evaluation, caregivers commented that using the Child Feeding Guide had made them aware of how their feeding behaviour can inadvertently affect their child. For instance, when introducing new food to a picky child’s diet, most parents will give up after less than ten attempts. However, research suggests that it can take 15 to 20 exposures before children are willing to put new foods in their mouths. In this case, factual knowledge makes it easier for parents to remain patient when dealing with their child’s choosiness. When knowledge is evidently lacking, there is a reasonable chance that more knowledge will lead to different behaviour, and the chances of reactance are limited because your design directly supports people to achieve their goals.

(2) The automaticity view: Eating behaviour is largely automatic, but we design for reflective processing

One reason for the relatively small effect of knowledge on eating behaviour lies in the fact that a very large part of our daily eating behaviour is automatic. Eating-related behaviour often occurs (at least partially) outside conscious awareness, are executed regardless of intent and are hard to control or stop through conscious scrutiny. We describe two different kinds of largely automatic eating behaviour: habits and impulses. Both have their unique impact on healthy eating. To change these different forms of automatic eating behaviour requires different kinds of design solutions.

Habits, defined here as ‘behaviour prompted automatically by situational cues, as a result of learned cue–behaviour associations’ (Wood & Neal, 2009, p. 580), determine the major part of our eating behaviour. Habit strength predicts our consumption of fruit and vegetables, soft drinks, meat, fish, snacks and crisps (see Van ‘t Riet et al., 2011, for an overview). Our habits help us to come to terms with the enormous complexity of everyday life, by taking away the burden of conscious deliberation from many uncritical decisions. Unfortunately, many of our habits have detrimental effects on our health (Hermsen et al., 2016). These undesired habits are hard to change because the rigid cue – response chain of a strong habit overrides contradictory behavioural intentions.

Eating rate, the speed at which we take in our food, is an example of a habit that is so deeply engrained, that it is nearly impossible to change by will power alone. A high eating rate is strongly associated with stomach disorders and being overweight (Robinson et al., 2014), which in itself causes a range of debilitating health issues, such as diabetes type 2 and some forms of cancer (Berenson, 2011). Conscious scrutiny is unable to change this kind of habitual behaviour, but a design that disrupts the habitual behaviour may enable us to slow down our eating rate. The 10sFork (SlowControl, Paris) gives gentle vibrations when we eat too fast (i.e., taking more than one bite per 10 seconds). New evidence (Hermsen et al., 2018) suggests that even a relatively short, one-month training period with the fork may be enough to slow down a person’s eating rate, with training effects still visible after two months without eating with the fork.

Changing existing habits is difficult; easier gains can be made with the introduction of new, beneficial feeding habits. For instance, many Australian schools take part in a program called Crunch & Sip, a set time during the school day to eat vegetables and fruit and drink water in the classroom. Children bring their own vegetables and fruit to school each day for the Crunch & Sip break. Each child also has a small clear bottle of water in the classroom to drink throughout the day to prevent dehydration. This is a simple, but powerful way to routinely establish an increased habitual consumption of fruit and vegetables. Similar interventions in scientific research have shown that even a short training period involving parents and children is able to instil healthier feeding habits that may very well last a lifetime (McGowan et al., 2013).

Habitual behaviours are automatically executed regardless of context. Other automatic eating behaviours, on the contrary, are more impulsive and completely set off by environmental cues. A powerful example of such impulsive behaviours can be found in supermarkets, where music, store design, product placement, advertisements, etc. influence food purchasing behaviour in ways that people cannot recognise or resist (Cohen & Babey, 2012). Key factors in our environment associated with overconsumption are the availability and easy accessibility of tempting, often high-calorie foods, the presence of overly large food portion sizes and price and marketing strategies that persuade purchasers to buy even more high-calorie or low-nutrient-dense products: ‘if you buy this, we will add a large soft drink for only €1’ (Poelman et al., 2014).

All these cues towards overconsumption are the result of designed interventions, be it in the form of marketing, urban planning or product and service design. If design can be used to drive us towards unhealthy eating, then designs that nudge us towards a healthier diet, or increase our awareness of our eating patterns, could also have great potential benefits. An example is the placement of products at the checkout counter. When unhealthy food at the checkout counter is replaced by healthy alternatives, two things happen. The strongest effect comes from removing the unhealthy cues and creating a new ‘default’ situation that does not invite you to do unhealthy impulse purchases. A smaller beneficial effect lies in an increase in sales of the healthy alternatives. Evidence for whether this latter strategy actually works is mixed, with some studies (e.g., Van Gestel, Kroese & De Ridder, 2017) finding support, and some studies (e.g., Chapman & Ogden, 2012) finding contrary results.

All in all, we can expect good designs that influence impulsive eating behaviour to be effective, but we cannot expect miracles. This is largely because our designed interventions have to compete with a myriad of other impulses. Moreover, it is useful to make a distinction between ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ interventions for healthy behaviour (Verplanken & Wood, 2006). Downstream interventions enable the easier performance of desired behaviour, such as improved designs for crossroads that speed up the circulation of traffic. Unfortunately, most interventions for healthy eating are ‘upstream’, i.e., aimed at avoiding or disrupting undesired behaviour. Poelman et al. (2014) list 32 different strategies to improve our food consumption, but all of them depend on a certain amount of willpower to succeed. To empower individuals to cope with the impulses generated by our food environment, we need to provide people with designs that improve their ability to self-regulate the amount of food they select and consume. How we achieve this remains a challenge.

(3) The social/cultural view: Too little focus on the (social) role of eating and its cultural connotations

Adding to the challenge sketched above is that food is about far more than just regulating our impulses and habits to optimalise the nutritional values that we consume. There is more than just an instrumental relationship between food and health, where food is seen as the instrument that can help us to acquire or sustain good health. The role that food plays in our daily lives is much more significant; food is connected to social contexts, cultural values and identities (Nordström et al., 2013).

Writing this just after the festive December month, it is very apparent how many socially and culturally defined food moments we encounter on a daily basis. The more traditional food moments during the end-of-year festivities are especially notable. In the Netherlands, for example, we eat ‘oliebollen’ (literally: ‘oil spheres’) at New Year’s – these are made by dropping a spoon full of dough into a deep fryer with hot oil. Certainly not the healthiest of traditions but we all indulge, later strengthening our New year’s resolutions to make up for our unhealthy behaviour. It’s the many smaller social and cultural food traditions that we encounter throughout the year that make it hard to stick to these resolutions. People are essentially social beings and from a very early age, we learn how to behave socially, including how, what, when and with whom we eat.

Starting at a very early age, cultural connotations and social interactions (with parents, siblings, friends) influence what children eat. Behaviour at the dinner table, parents’ own ideas about what constitutes a healthy meal, as well as their ideas of what constitutes a palatable meal, all influence what and how children eat. The Loughborough Child Feeding Guide mentioned earlier therefore not only provides knowledge about what is healthy, but also about how social interactions influence eating. As an example, Walton et al. (2017) describe that parents of children who will not eat vegetables, eat fewer vegetables themselves as well.

Later in life, our peers more often than not influence our food choices. People are very sensitive to social norms, and are always, consciously and unconsciously, on the lookout for potential norm violations. Social modelling in eating behaviour is a robust and often-replicated phenomenon (Robinson et al., 2014). We automatically adapt our portion size, and even our menu choices, to those around us, regardless of whether we know or like those who influence us (Christie & Chen, 2018).

This implies that, even if we have made the decision to adapt to a healthier lifestyle, it is extremely difficult to balance this with the cultural and social norms we are confronted with. The mere desire to live a healthier life introduces food dilemmas on a daily basis. This can cause people to stay in a phase of contemplation, thinking about a desire to change while not being able to actually make any sustained changes (Ludden et al., 2017). A ‘process of change’ that people reported to have used to progress through the contemplation stage is self-reevaluation (Prochaska et al., 1992) which involves cognitive reappraisal of how behaviour change is part of one’s identity. This process has, for example, been found to be important for women’s decisions to eat more fruit (Chung et al., 2006). Lifestyle interventions might be more successful if this concept is integrated in their design in a way that it connects to people’s direct social environment.

While the social and cultural ties to our decisions to consume food are complex and strong, understanding them offers new prospects for designed interventions. For example, we might incorporate social modelling in our designs. There is no better way to get toddlers to accept new foods than repeatedly seeing parents eat them, and there is no stronger influence on adolescents’ and adults’ behaviour than seeing peers or idols perform the desired behaviour. When Dutch researchers (Zeinstra, Kooijman & Cremer, 2017) exposed children to movie clips of famous, well-liked TV stars eating carrots, this increased the number of carrots the children ate, even after nine months. However, as with all designs aimed at unconscious processing, the effects of such designs may be limited by competing impulses. Evidence tells us that we adapt the amount we eat to those we eat with (Hermans et al., 2008), but this effect is mitigated by a range of factors such as the weight, gender and familiarity of the co-eater, the quality of the social interaction between co-eaters and the initial hunger rate (see Houldcroft, Haycraft & Farrow, 2014, for an overview of sources).

Difficulties notwithstanding, any design that does not take cultural and social aspects into account will never be successfully, let alone sustainably, adopted. Social and cultural food traditions such as those described in this section are of course defined by and often limited to a specific group of people (living in a cultural tradition, family, etc.). This means that any designed intervention should take into account the specific traditions of the group it is designed for. All efforts aimed at designing one healthy behaviour guide for everyone are bound to fail.

(4) The engagement view: Designed interventions aimed at healthy eating are often unengaging and frustrating

The automaticity of much behaviour related to eating and the strong cultural and social connotations associated with eating, make it hard to change undesired nutritional behaviour for the better. This problem calls for engaging designs, that optimally support people in their behaviour changes. Unfortunately, most designs for healthy eating have engagement issues that can be explained by looking at the key components of engagement: involvement and enjoyment (Crutzen, Van ‘t Riet & Short, 2016; Perski et al., 2017). Involvement relates to the actual use of the intervention (behavioural component) and enjoyment relates to positive affect and feelings of control (experiential component).

Looking at these components, it is not difficult to find examples of how current design interventions aimed at healthier eating are not engaging. The 10sFork may be an effective tool in decelerating eating rate, but it has trouble engaging its target group. Self-perceived fast eaters with eating rate-related complaints such as overweight and stomach problems, often will not consider using the fork: they tend to see using the fork as just too much hassle. Besides, eating rate, however detrimental, is not seen as a priority by this group (Hermsen et al., 2016).

As another example, consider the SmartBite-system, a device that is placed in the mouth only when eating. It reduces the volume within the mouth while supporting more mindful eating. The device showed promising effects: people using the SmartBite-system lost weight (Ryan et al., 2017). However, the system faced serious adherence problems despite the good results that were obtained. Apparently, people were not willing to use the device for longer periods of time, possibly because it diminished their joy and comfort while eating.

Other designed interventions, which are less invasive, also face serious adherence problems that can be related back to a lack of engagement. Generally, 80 per cent of health apps are abandoned in the first week (Chen, 2015). Using designs for healthy eating is often hard, boring work and not at all enjoyable. For example, tracking food intake still requires manual input of every bite we take. So far, we haven’t been able to develop sensors that do this task for us although serious efforts to solve this problem have been made recently (Tseng et al., 2018). The amount of effort that is required to use the currently available interventions combined with the lack of joy and the feeling of not being in control stands in the way of the sustained use of such interventions. Arguably, there have been efforts to increase enjoyment while using health behaviour change interventions, but these have mostly focused on introducing (elements of) gaming in interventions and as such do not really make the change itself more enjoyable (Hopkins & Roberts, 2015).

Current efforts also lack an important further dimension that comes into play when longer-term use of interventions is warranted: dynamics. O’Brien and Toms (2008) critically deconstructed the term engagement in design and describe four different phases within a process of engagement: the point of engagement, the period of engagement, disengagement and re-engagement. These phases are supported by different attributes, which means that what makes a person engage for the first time (point of engagement) might differ from what keeps a person engaged. From a design perspective, this makes perfect sense: we need to design for the way people actually behave, and not for the way designers or policy-makers and health professionals want them to behave (Norman, 2007). This may seem contradictory, since the aim of these interventions is to change people (or at least their behaviour). However, if we see people’s behaviour as dynamic rather than static, and design interventions that can adapt to such changes, we might be able to come to sustained engagement.

Conclusion and discussion

The previous sections have made clear that lifestyle behaviour change (specifically, adopting healthier nutrition behaviour) is difficult to accomplish. Together, the four views that we have discussed lay out the challenges that people face in trying to follow healthy nutrition patterns. Unhealthy nutrition behaviour is not only a matter of (lack of) knowledge or of the attitudes of an individual. The social/cultural view described above has shown that it is also affected by social (eating and being physically active are often social activities), cultural and societal (e.g., (un)healthy food availability, built environment) conditions.

The four views adopted thus show how our complete food system works against adopting healthy nutrition patterns. Parkinson and colleagues (2017) have introduced the food system compass that introduces different levels in the system of food consumption. Next to a way of mapping how our food system can work against adopting healthy food patterns, we can also use it as a starting point for thinking about how to connect the different levels through design in order to support healthier eating behaviour. The most successful endeavours to change people’s behaviour have combined interventions in multiple environments (at home, at school, at the sports club) and have focused on groups rather than on individuals (Arden-Close & McGrath, 2017; Steenkamer et al., 2017). If we see behaviour as a consequence of both environment and the individual acting in that environment it makes sense to design interventions that include both of these rather than focusing on one or the other. Design and technology, as contextual factors, can take a mediating role in human interaction with the environment. Promising opportunities to create change lie in designing for both ends of the agency divide as well as in the interaction between the two. Monitoring and coaching technology has developed towards personalised solutions but have so far not always included environmental and social context. Arguing from the other end of the continuum, larger numbers of people can be reached by designing (interventions in) the environment as a trigger and connecting to personal interventions once the trigger has worked, using a sequential design.

In the next sections, we will discuss a series of promising avenues for design to initiate change at different levels of the food system in a more creative and more holistic way.

Food design aimed at healthy eating behaviour

The design of food itself offers a largely untapped potential to influence the way we perceive food. Whereas the food industry has for decades focused on innovating food so that people would find it most desirable (sweet, fat), they are now to some extent taking responsibility by trying to find solutions to decrease percentages of sugar and salt while preserving taste. Schifferstein (2016) has elaborately discussed what design can bring to the food industry. Indeed, independent designers and researchers are using health as well as sustainability challenges as starting points to design alternative food products. Think for example of the different view on food and health that Naomi Jansen presents with her ‘chocobombes’ (www.chocobombes.nl), a series of boxes with chocolates designed to provide pregnant women with much needed moments of comfort whilst pointing out the benefits of healthy nutrition during pregnancy. Or, consider the variety of ways in which food designer Marije Vogelzang creates new perspectives on food by design, for example by designing new vegan eating experiences (e.g., Plantbones, www.marijevogelzang.nl). Alternative strategies for food (and food packaging) designers lie in the application of insights from research on multisensory perception. Research on cross-modal interactions have indicated that these can influence our perception of food (Harrar & Spence, 2013; Spence, 2017; Becker et al., 2011). There is much to be gained in designing improved experiences of taste, texture and smell of healthy nutritional alternatives to readily available snacks, for example. Such designs do not overly rely on knowledge, can contribute to encourage healthier impulsive eating, are not affected by social and cultural functions of eating and increase engagement.

Designing a healthy food environment

A second promising possibility for design to initiate change towards healthy nutrition lies in designing the environment, both in retail and in public space. Our current obesogenic environment does not encourage healthy eating at all. This situation has direct consequences, especially for those with limited health literacy (Ball, 2015). Groups with lower socioeconomic status often face financial barriers to purchasing healthy food. Furthermore, particularly in the US, they may have limited access to healthy food, have experienced limited exposure to healthy foods in early life, which has negatively shaped taste preferences and habits, and experience a lack of social support and negative social norms related to healthy eating. In many countries, low-status occupations also pose additional challenges, with long, inflexible hours, challenging conditions and low benefits (ibid.). Finally, poverty limits people’s cognitive resources, which decreases their ability to self-regulate behaviour (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). Health disparities, therefore, need addressing at an environmental level, by reducing the availability and attractiveness of unhealthy choices, increasing the availability and attractiveness of healthy alternatives, and placing our designs in environments that are within the reach of less fortunate groups. Such changes cannot be achieved by designers alone. For healthy food environments, policy changes are necessary. The potential for (local) governments to positively affect citizens’ health is large. An example is the effect of the introduction of a sugar tax, which decreased peoples’ intake of sodas in Mexico and some communities in the United States (Roach & Gostin, 2017). All in all, a healthy food environment makes healthy automatic eating behaviour possible and makes it easier to engage with healthy eating without the need for infinite amounts of willpower.

Designing for social systems

Most of our designed interventions for healthier eating are aimed at the individual. However, there is a growing body of evidence that shows that for groups with lower health literacy, only interventions that contain a social element are effective (Cleland et al., 2012). Community-based programmes, or interventions that involve some sort of support group, can be a successful way not only to increase engagement in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, but also to support them in achieving lasting behaviour change. A vital ingredient is the embedding of interventions in existing settings, such as the workplace (with ample support from colleagues and management) or the local supermarket.

A social system that has a profound influence on eating behaviour, and is currently largely overlooked in (design) research, is the family. Families shape our nutritional habits and preferences, and the family setting is the backdrop for most of our eating behaviour. The effect of our ‘individual’ designs on a family setting is an under-researched, but potentially beneficial topic. Does the 10sFork (that reduces eating rate) affect other eaters in a family? Does the MindFull soup bowl ‘work’ in a family setting, or does its trickery get called out? Future research will tell us. In the meantime, designs aimed at the social system will increase engagement, and encourage healthy interpretation of the social and cultural functions of eating.

Healthy eating, greater wellbeing

All in all, designing for healthy eating has great potential to contribute to our wellbeing. Well-designed interventions for healthy eating help us achieve a greater quality of life for a longer period. Furthermore, they can do so without us having to give up enjoyment. Future healthy food designs will hopefully allow us to consume healthy foods and drinks we enjoy without concessions to the self-indulgent, social and cultural functions of eating. To do so, we must carefully orchestrate our designs so that they contain components aimed at knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating, components affecting the social context of our eating behaviour, and components aimed at a healthier food environment.

References

- Andereae, H. (2017). MindFull: Tableware to manipulate sensory perception and reduce portion sizes. In Dr. Elif Ozcan (Ed.), Proceedings of the Conference on Design and Semantics of Form and Movement – Sense and Sensitivity, DeSForM 2017. InTech.

- Arden-Close, E., & McGrath, N. (2017). Health behaviour change interventions for couples: A systematic review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 22(2), 215–237.

- Ball, K. (2015). Traversing myths and mountains: Addressing socioeconomic inequities in the promotion of nutrition and physical activity behaviours. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1).

- Bates, B., Lennox, A., Prentice, A., et al. (2014). National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Results from Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Combined of the Rolling Program (2008/9 – 2011/12). England: Public Health.

- Becker, L., Van Rompay, T.J.L., Schifferstein, H.N.J., & Galetzka, M. (2011). Tough package, strong taste: The influence of packaging design on taste impressions and product evaluations. Food Quality and Preference, (22), 17–23.

- Berenson, G.S. (2011). Health consequences of obesity. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 58(1), 117–121.

- Chapman, K., & Ogden, J. (2012). Nudging customers towards healthier choices: An intervention in the university canteen. Journal of Food Research, 1(2).

- Chen, A. (2015). New Data Shows Losing 80% of Mobile Users is Normal, and Why the Best Apps Do Better. Retrieved 17 May 2016. Available from: http://andrewchen.co/new-data-shows-why-losing-80-of-your-mobile-users-is-normal-and-that-the-best-apps-do-much-better/(archived by Webcite at http://www.webcitation.org/6hjwoLkyM).

- Christie, C.D., & Chen, F.S. (2018). Vegetarian or meat? Food choice modeling of main dishes occurs outside of awareness. Appetite, 121, 50–54.

- Chung, S.J., Hoerr, S., Levine, R., & Coleman, G. (2006). Processes underlying young women’s decisions to eat fruits and vegetables. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 19, 297–298.

- Clark, G.L. (2010). Human nature, the environment, and behaviour: Explaining the scope and geographical scale of financial decision-making. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 92(2), 159–173. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0467.2010.00340.x.

- Cleland, V., Granados, A., Crawford, D., Winzenberg, T., & Ball, K. (2012). Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity among socioeconomically disadvantaged women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 14(3), 197–212.

- Cohen, D.A., & Babey, S.H. (2012). Contextual influences on eating behaviours: Heuristic processing and dietary choices. Obesity Reviews, 13(9), 766–779.

- Crutzen, R., van’t Riet, J., & Short, C.E. (2016). Enjoyment: A conceptual exploration and overview of experimental evidence in the context of games for health. Games for Health Journal, 5(1), 15–20.

- Dassen, F.C.M., Houben, K., Van Breukelen, G.J.P., & Jansen, A. (2017). Gamified working memory training in overweight individuals reduces food intake but not body weight. Appetite.

- De Korne, D.F., Malhotra, R., Lim, W.Y., Ong, C., Sharma, A., Tan, T.K., … and Østbye, T. (2017). Effects of a portion design plate on food group guideline adherence among hospital staff. Journal of Nutritional Science, 6.

- Dixon, H., Borland, R., DSegan, C., Stafford, H., & Sindall, C. (1998). Public reaction to Victoria’s ‘2 Fruit “n” 5 Veg Every Day’ campaign and reported consumption of fruit and vegetables. Preventive Medicine, 27, 572–582.

- Hanks, A.S., Just, D.R., Smith, L.E., & Wansink, B. (2012). Healthy convenience: Nudging students toward healthier choices in the lunchroom. Journal of Public Health, 34(3), 370–376.

- Harrar, V., & Spence, C. (2013). The taste of cutlery: How the taste of food is affected by the weight, size, shape, and colour of the cutlery used to eat it. Flavour, 2(1), 21.

- Haycraft, E., Witcomb, G., & Farrow, C. (2016). Development and preliminary evaluation of the Child Feeding Guide website and app: A tool to support caregivers with promoting healthy eating in children. Frontiers in Public Health, 4.

- Hermans, R.C.J., Larsen, J.K., Herman, C.P., & Engels, R.C.M.E. (2008). Modeling of palatable food intake in female young adults: Effects of perceived body size. Appetite, 51, 512–518.

- Hermans, R.C., de Bruin, H., Larsen, J.K., Mensink, F., & Hoek, A.C. (2017). adolescents’ responses to a school-Based Prevention Program Promoting healthy eating at school. Frontiers in Public Health, 5(309), 1–11.

- Hermsen, S., Frost, J., Renes, R.J., & Kerkhof, P. (2016). Using feedback through digital technology to disrupt and change habitual behaviour: A critical review of current literature. Computers in Human Behaviour, 57, 61–74.

- Hermsen, S., Frost, J.H., Robinson, E., Higgs, S., Mars, M., & Hermans, R.C.J. (2016). Evaluation of a smart fork to decelerate eating rate. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(7), 1066–1068.

- Hermsen, S., Mars, M., Higgs, S., Frost, J., & Hermans, R. (2018, December 12). Effects of eating with an augmented fork with vibrotactile feedback on eating rate and body weight: A randomized controlled trial. Preprint ahead of publication, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/n328p

- Hopkins, I., & Roberts, D. (2015). ‘Chocolate-covered Broccoli’? Games and the teaching of literature. Changing English, 22(2), 222–236.

- Houldcroft, L., Haycraft, E., & Farrow, C. (2014). Peer and friend influences on children’s eating. Social Development, 23(1), 19–40.

- Jefferey, R.W., French, S., Raether, C., & Baxter, J.E. (1994). An environmental intervention to increase fruit and salad purchases in a cafeteria. Preventive Medicine, 23, 788–792.

- Johnson-Glenberg, M.C., & Hekler, E.B. (2013). ‘Alien Health Game’: An embodied exergame to instruct in nutrition and MyPlate. Games for Health Journal, 2(6), 354–361.

- Kramish Campbell, M., Reynolds, K.D., Havas, S., Curry, S., Bishop, D., Nicklas, T., … and Heimendinger, J. (1999). Stages of change for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among adults and young adults participating in the national 5-a-day for better health community studies. Health Education Behavior, 26(4), 513–534.

- Kelders, S.M., Van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C., Werkman, A., Nijland, N., & Seydel E. (2011). Effectiveness of a Web-based intervention aimed at healthy dietary and physical activity behaviour: A randomized controlled trial about users and usage. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(2), e32.

- Larsen, J.K., Hermans, R.C.J., Sleddens, E.F.C., Vink, J.M., Kremers, S.P.J., Ruiter, E.L.M., & Fisher, J.O. (2018). How to bridge the intention-behaviour gap in food parenting: Automatic constructs and underlying techniques. Appetite, 123, 191–200.

- Lee, I.M., Shiroma, E.J., Lobelo, F., Puska, P., Blair, S.N., & Katzmarzyk, P.T. (2012). Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet, 380(9838), 219–229.

- Lloyd, J., Creanor, S., Logan, S., Green, C., Dean, S.G., Hillsdon, M., … and Wyatt, K. (2018). Effectiveness of the Healthy Lifestyles Programme (HeLP) to prevent obesity in UK primary-school children: A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(1), 35–45.

- Ludden, G.D.S. (2017). Design for healthy behaviour. In K. Niedderer, S. Clune, & G. Ludden (Eds.), Design for Behaviour Change – Theories and Practices of Designing for Change. London: Routledge.

- Ludden, G. Ozkaramanli, D., & Karahanoğlu, A. (2017). Can you have your cake and eat it too? A dilemma-driven approach to design for the early stages of health behaviour change. Proceedings of Design4Health, 4–7 December, Melbourne, Australia.

- Ludden, G.D.S., & Hekkert, P. (2014). Design for healthy behavior. design interventions and stages of change. Paper Presented at The Ninth International Conference on Design and Emotion, Bogota, Colombia, October 6–9.

- Marteau, T.M. (2018). Changing minds about changing behaviour. The Lancet, 391(10116), 116–117.

- McCarthy, M., Brennan, M., Kelly, A.L., Ritson, C., De Boer, M., & Thompson, N. (2007). Who is at risk and what do they know? Segmenting a population on their food safety knowledge. Food Quality and Preference, 18(2), 205–217.

- McGowan, L., Cooke, L.J., Gardner, B., Beeken, R.J., Croker, H., & Wardle, J. (2013). Healthy feeding habits: Efficacy results from a cluster-randomized, controlled exploratory trial of a novel, habit-based intervention with parents. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 98(3), 769–777.

- Mhurchu, C.N., Aston, L.M., & Jebb, S.A. (2010). Effects of worksite health promotion interventions on employee diets: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 62.

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much. New York, NY: Time Books, Henry Holt & Company LLC.

- Netherlands Health Council (2015). Richtlijnen goede voeding 2015. The Hague, Netherlands: Gezondheidsraad; Publication No. 2015/24. Retrieved from: https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/sites/default/files/201524_richtlijnen_goede_voeding_2015.pdf. Accessed 08 January 2018. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6wJgIG9BR).

- Niedderer, K. Clune, S., & Ludden, G. (2017). Summary of design for behavioural change approaches. In K. Niedderer, S. Clune, & G. Ludden (Eds.), Design for Behaviour Change – Theories and Practices of Designing for Change. London: Routledge.

- Nordström, K., Coff, C., Jönsson, H., Nordenfelt, L., & Görman, U. (2013). Food and health: Individual, cultural, or scientific matters? Genes & Nutrition, 8(4), 357–363.

- Norman, D.A. (2007). The Design of Future Things. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- O’Brien, H.L., & Toms, E.G. (2008), What is user engagement? A conceptual framework for defining user engagement with technology. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 59, 938–955.

- Parkinson, J., Dubelaar, C., Carins, J., Holden, S., Newton, F., & Pescud, M. (2017). Approaching the wicked problem of obesity: An introduction to the food system compass. Journal of Social Marketing, 7(4), 387–404.

- Perski, O., Blandford, A., West, R., et al. (2017). Behavioral Medicine: Practice, Policy, Research, 7(2), 254–267.

- Poelman, M.P., de Vet, E., Velema, E., Seidell, J.C., & Steenhuis, I.H.M. (2014). Behavioural strategies to control the amount of food selected and consumed. Appetite, 72, 156–165.

- Prochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C., & Norcross, J.C. (1992). In search of the structure of change. In Y. Klar, J.D. Fisher, J.M. Chinsky, & A. Nadler (Eds.), Self Change - Social Psychological and Clinical Perspectives (pp. 87–114). New York: Springer - Verlag.

- van’t Riet, J., Sijtsema, S.J., Dagevos, H., & De Bruijn, G.-J. (2011). The importance of habits in eating behaviour. An overview and recommendations for future research. Appetite, 57(3), 585–596.

- Roache, S.A., & Gostin, L.O. (2017). The untapped power of soda taxes: Incentivizing consumers, generating revenue, and altering corporate behavior. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6(9), 489–493.

- Robinson, E., Almiron-Roig, E., Rutters, F., de Graaf, C., Forde, C.G., Tudur Smith, C., … and Jebb, S.A. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the effect of eating rate on energy intake and hunger. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(1), 123–151.

- Robinson, E., Thomas, J., Aveyard, P., & Higgs, S. (2014). What everyone else is eating: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of informational eating norms on eating behaviour. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114(3), 414–429.

- Ryan, D.H., Parkin, C.G., Longley, W., Dixon, J., Apovian, C., & Bode, B. (2017). Efficacy and safety of an oral device to reduce food intake and promote weight loss. Obesity Science & Practice.

- Schifferstein, H.N.J. (2016). Food design: Connecting disciplines. International Journal of Food Design, 1(2), 79–81.

- Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention – behaviour relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1–36.

- Spence, C. (2017). Gastro-physics. The New Science of Eating. London, UK: Viking. ISBN:9780241270097.

- Stark Casagrande, S., Wang, Y., Anderson, C., & Gary, T.L. (2007). Have Americans increased their fruit and vegetable intake? The trends between 1988 and 2002. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(4), 257–263.

- Steenkamer et al. (2017). Outcome monitor aanpak gezond gewicht 2017. Gemeente Amsterdam, Amsterdam.

- Tseng, P., Napier, B., Carbarini, L., Kaplan, D.L., & Omenetto, F.G. (2018). Functional, RF-trilayer sensors for tooth mounted, wireless monitoring of the oral cavity and food consumption. Advanced Materials, 30(18).

- Van Gestel, L.C., Kroese, F.M., & De Ridder, D.T.D. (2017). Nudging at the checkout counter – A longitudinal study of the effect of a food repositioning nudge on healthy food choice. Psychology & Health, 1–10.

- Verplanken, B., & Wood, W. (2006). Interventions to break and create consumer habits. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 90–103.

- Walton, K., Kuczynski, L., Haycraft, E., Breen, A., & Haines, J. (2017). Time to re-think picky eating?: A relational approach to understanding picky eating. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1).

- Wang, Y., & Lim, H. (2012). The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. International Review of Psychiatry, 24(3), 176.

- WHO (2019). Factsheet Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed September 5 2019.

- Wood, W., & Neal, D.T. (2009). The habitual consumer. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19, 579e592.

- Zeinstra, G.G., Kooijman, V., & Kremer, S. (2017). My idol eats carrots, so do I? The delayed effect of a classroom-based intervention on 4–6-year-old children’s intake of a familiar vegetable. Food Quality and Preference, 62, 352–359.