Chapter 11

Standard Speech System

There are many kinds of speeches, but as the title “standard speech system” indicates, I'm not being overly specific here. For the purposes of this chapter, a speech is defined as any sort of spoken presentation, toast, message, sermon, or lecture that has been prepared in advance. This system is very flexible and can be used in many different settings. With some practice, you should be able to adapt it to your specific needs.

Because it is the first system, we'll take a little longer with it, but this discussion is still very brief. If you want a more complete treatment, please see my book Write to Speak, from which this chapter is adapted.1

Getting Started

Julia Andrews, playing Maria in The Sound of Music, said—sang, actually—that the beginning is a very good place to start. While that may be true of learning musical notes (though I never personally learned them), it's not true of writing a speech. The beginning is pretty much the very worst place to start. Why? Two reasons:

- First, you can't really write the introduction until you know what you're going to say in the rest of the speech. The introduction is actually the last part you'll write in this system.

- Second, the beginning is also the hardest part to write. You'll experience the pressure to find the perfect opening sentence and struggle to settle on the right first word. Before you know it, you're paralyzed with second guesses and bingeing Game of Thrones sounds much better than writing. It's better to start with something that builds momentum, not stops it. However, if some burst of inspiration for the intro hits you, you should write it and keep going as long as it flows. Stop when it stops and go back to what you were doing.

So, if you're not supposed to start at the beginning, where should you start? Read on for the six steps of the standard speech system.

1. Start with the Questions

The questions are:

- Why am I giving this speech? Why do I care?

- What is the purpose of the speech?

- Who is the audience?

- Why should they care?

- What is the point?

Do those sound familiar? If you're old enough or know your classic movies, you should be hearing Mr. Miyagi saying, “Wax on, wax off” right about now. (And if you have no idea what I'm talking about, you need to watch Karate Kid, vintage 1984, which is the source material for Cobra Kai on Netflix.) The point is that all the lessons you've learned in this section have intentionally led to this. If you did your work in Chapters 8 and 9, you've basically completed this first step.

a. Why Am I Giving This Speech? Why Do I Care?

On the top of the first page of your speech, write “I am giving this speech because ____.” This question brings your speech back to your identity—because you are the message (Chapter 2). Don't settle on surface answers like, “My boss told me to” or “It's my duty as the maid of honor.” Instead, dig deeper and connect it to your mission and values (Chapter 4), such as communicating something you believe in, honoring your best friend, or providing clarity to your colleagues.

The goal of this question is to ground your speech in something you care about because you'll be confident in what you care about. Conviction amplifies confidence.

Conviction amplifies confidence.

So, if I were preparing a speech on using systems for speech writing, I might write, “My mission is to help people realize their potential. I believe this tool can help them reach new heights.”

b. What Is the Purpose of the Speech?

Next, write, “The purpose of my speech is to_____.” Use action words—like persuade, inform, motivate—followed by the content. So, it may read, “The purpose of my speech is to convince my listeners to use my systems for writing their speeches.”

The verb you choose will be driven by what kind of speech you are giving. Here are the four broad categories and some of the action words you could use with each:

- Informative speech: Inform, show, demonstrate, prove, or educate.

- Persuasive speech: Persuade, prove, motivate, convince, sell, or pitch.

- Entertainment speech: Entertain, make laugh, or lighten moods.

- Special event speech: Honor, eulogize, celebrate, or connect.

Try to make this purpose statement as brief, clear, and specific as possible. The longer, vaguer, and more confusing it is, the less effective it will be.

c. Who Are the Audience?

Under the purpose, write, “My audience will be_____.” You don't need to write a multipage profile, just enough to summarize the research you did from Chapter 9. So, I might write, “My audience will be middle‐management professionals who are intimidated by writing speeches.”

d. Why Should They Care?

Write, “The reason they care is____.” Do not skip this step. It's the key to an eager audience and keeps you focused on serving them. This in turn increases confidence in your message. So, I could write, “The reason they care is because great public speaking skills make them more valuable and can enhance their earning potential.”

e. What Is the Point?

Finally, write, “The point of my speech is_____.” As I said in Chapter 8 and 9, the point should tie the speech's purpose with the audience's reason for caring and be expressed as the singular thing you want them to know/do. So, I might write, “The point of my speech is that, by using my system, my audience can write better speeches in less time, increasing their confidence and effectiveness.”

(Note: You can download a template of these questions at connect.mikeacker.com.)

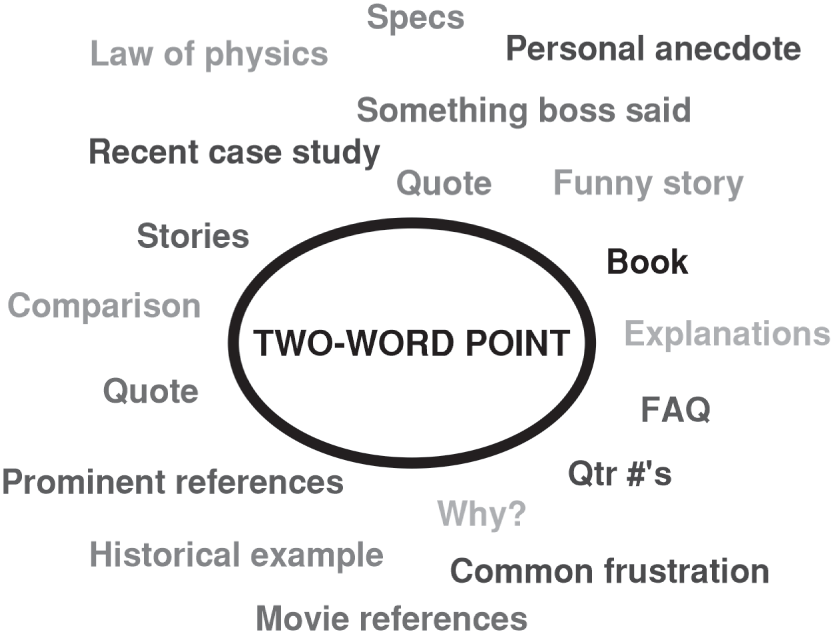

2. Brainstorm Using a “Mind Map”

A mind map is simply a diagram used for the purpose of visually organizing information. It's been around for a while, but I've found it works especially well as a brainstorming tool. Because it is a tool, you shouldn't feel chained to a specific method, but start with this one and then figure out what works best for you.

Mind mapping is primarily a brainstorming session, and the most important principle of brainstorming is no filter. Write whatever comes to your mind without editing—yet. In his presentation on creativity, Monty Python's John Cleese talked about the two modes of thinking and their respective value:

We all operate in two contrasting modes, which might be called open and closed. The open mode is more relaxed, more receptive, more exploratory, more democratic, more playful, and more humorous.

The closed mode is the tighter, more rigid, more hierarchical, more tunnel‐visioned. Most people, unfortunately, spend most of their time in the closed mode. Not that the closed mode cannot be helpful.

If you are leaping a ravine, the moment of takeoff is a bad time for considering alternative strategies. When you charge the enemy machine‐gun post, don't waste energy trying to see the funny side of it. Do it in the “closed” mode.

But the moment the action is over, try to return to the “open” mode—to open your mind again to all the feedback from our action that enables us to tell whether the action has been successful or whether further action is needed to improve on what we have done. In other words, we must return to the open mode because in that mode we are the most aware, most receptive, most creative, and therefore at our most intelligent.2

His point throughout the presentation is that open and closed thinking are necessary at certain times. Create in open. Evaluate the creation in closed. Brainstorming must be done in open mode—stream of consciousness, quantity over quality, there is no such thing as a bad idea, and so forth. You need to get into an almost playful mindset to brainstorm well. Yes, this even applies to more serious topics, such as quarterly reviews, board presentations, and memorials. It can open your mind to unexpected insights.

When brainstorming, I use a mind map to both gather and guide my work. A mind map can be created electronically, using a computer or tablet, or by using a physical medium (such as paper or sticky notes on a board). Both have their advantages and disadvantages. The electronic form is easier to save, edit, and share but is more prone to distractions (such as technical difficulties and having easy access to the internet). The simplicity of paper and the tactile nature of handwriting allow creativity to flow, but it's easily lost and harder to edit. Experiment with each and see which works best for you.

Begin by writing the one‐ to two‐word version of your point in the middle of the page.

Now, brainstorm any material you might want to share about your topic. Here are some questions to get you started. The purpose of your speech may affect which questions are more relevant, but don't try to guide your brainstorming (remember, you're in open mode now):

- What do my listeners need to know about my topic?

- Why do I care about it? What is my personal history with it?

- What sort of things do I tend to say about my topic in casual conversations?

- What proof or evidence do I have?

- What are some common objections?

- What are some supporting materials—statistics, examples, stories, analogies, etc.—I can use?

- What are some parallel ideas to my topic?

- What have others said about it?

- How has my topic shown up in the business world or popular culture?

Notice that I didn't use full sentences or complete thoughts. You only need enough to remember what you meant. As you brainstorm, you might see some sort of order develop. Maybe certain ideas easily lend themselves to ones already on the page, so you cluster them around each other. This is where the sticky note method can be advantageous.

Ideally, you shouldn't do all your brainstorming in one session. Your brain will keep working in the background even when you walk away. It's not uncommon to get your best material in the second session—or even when you're doing something completely unrelated.

When are you done? The short answer is when you have a good deal more material than you'll need. Think of it this way: Imagine that you're building a tree fort in your backyard. The cost of the materials is no issue, but the hardware store is two hours from the house. If at all possible, you want to get all of your supplies in one trip, so you get extra of everything. Better too many nails than a trip back to the hardware store. At the same time, you wouldn't want to go crazy because you'll have to sort and carry everything you buy. You'll basically keep your purchases proportional to the size of the tree house you have planned. That is to say, the longer and more complex the topic, the more material you'll need.

3. Organize Your Points

Once you're satisfied with your material, you'll need to shift from open to closed mode. It's time to evaluate, categorize, and organize everything you did in the last step. First, a general word about the structure of speeches. The specifics will be driven by the purpose of your speech, but every speech consist of three parts:

- The introduction functions the same as the introduction of a book. Its one purpose is to hook the audience and keep them listening. An introduction shouldn't offer any complete ideas but only make promises about what the body will provide.

- The body contains all the actual content of the speech and does the heavy lifting.

- The conclusion should not contain any new information. Its purpose is to summarize what has been said and tell the listener what to do/feel/think next.

The introduction and conclusion each get their own steps, so we're not going to worry about them too much now other than setting aside any brainstorming material that seems useful. Because the body is longer and more complex than the other parts, it can seem more intimidating. But it only has to be as difficult as you make it.

If you're a student of design, you've heard of things like the golden ratio, the rule of thirds, the Fibonacci Sequence, and the principle of symmetry. There are some arrangements that are more naturally pleasing to the human eye and mind. The number three holds the same power in communication. For whatever reason, we are naturally inclined to express and—more importantly—remember things in groups of three. One example is the adage that “bad things come in three.” It's not at all true, but we naturally group events in threes (especially in the Western world). The point is you can use this inclination to your advantage by sticking with the three‐point speech.

Humans are naturally inclined to express and remember things in groups of three.

Sometimes, my clients question my suggestion of three‐point speeches. I can't blame them. I did the same for years. Three‐point speeches seemed so ordinary. Over the years, I've experimented with all kinds of “more creative” speeches. Sometimes, they worked; more often they flopped, and they always took way more time and effort. Remember, your goal isn't to write the next Gettysburg Address. You just want a really good speech that will effectively communicate your main point with minimum hair‐pulling.

Here's the painless way to organize your speech. Begin by going through all your material from the 10,000‐foot view to get a sense of the overarching ideas. Look for the three most important ideas, which will become your three points. What if you can't narrow it down to three? Hang on to the extra ones for now, but keep looking for ways to combine them. You may not be able to—a speech about the six steps of the standard speech system will require six steps. But remember this: The more points a speech has, the less likely your audience will be able to remember them. As I said in Chapter 7, you can't change how much listeners is able to retain, but you can change the likelihood of them remembering the things you want them to.

The more points a speech has, the less likely your audience will be able to remember them.

So, now, you (ideally) have three highly focused points, which I call “buckets.” They are the containers that will hold all the speech's key information. They literally give the audience a place to put everything they hear, so they can carry it away with them. Hence, buckets.

Here's how buckets aid remembrance. If you were to ask me what toys my son likes to play with (which would be kind of weird, but let's go with it), I could pull fifty toys off his shelf and announce them one by one. How many of the fifty do you think you'd remember an hour later? Maybe the first couple and the last one (because you were so relieved it was the last) and maybe a few in the middle.

Let's say I understand the power of buckets, so instead I grab about a dozen toys and items and sort them into the three buckets: action figures, Hot Wheels, and DJ equipment (yes, my six‐year‐old son likes to DJ—he offers a special rate for birthday parties, if you're interested) and then talk about each bucket. An hour later, you might still remember all twelve objects. You would've seen fewer of his toys than with the no‐bucket approach but would remember more (that's key—less is more), and you'd have a far better understanding of my son's play habits.

So, once you have chosen your three buckets, go through all your material again, this time examining each piece and placing them in one of six categories:

- Introduction: Material that elicits interest, presents problems that need to be solved, makes promises about the body, etc.

- Bucket 1

- Bucket 2

- Bucket 3

- Conclusion: Material that summarizes the buckets and presents next steps.

- Unsorted: Perhaps the most useful category because it's easier to set aside the one great idea that doesn't really fit than it is to toss it.

This is where the sticky note method is nice—you can physically move them around and try different arrangements. Does the story about the python in your basement go better with Bucket 1 or Bucket 2? Just move it back and forth, and see what feels better.

Once you have sorted all your brainstorming material into one of these categories (and tossed any that didn't make the cut), step away for a while, allowing yourself to return to open mode. Go do something fun, work on a different project, exercise, sleep on it. Your brain will keep working.

When you return, take a fresh look at your categories and the material in them. Does Bucket 1 need less content? Should more material be sent to “Unsorted”? If you have more than three buckets, can any of them be combined or eliminated?

Now, it's time to examine your buckets individually. As I've already indicated, you must be absolutely clear about the central idea of each point. If it isn't clear in your head, it won't be clear to your audience.

If it isn't clear in your head, it won't be clear to your audience.

One of the best tools for focusing your points is naming them, that is, creating titles. A great title will practically write the point. My fourth book began with nothing more than the idea for a title, Lead with No Fear. These titles can describe the content of buckets, present actions to be taken, be pithy one‐liners, or be chronologically or process‐driven (i.e. Step 1, Step 2, Step 3). When it comes to titles, clarity is better than cleverness. It doesn't matter how creative it is if the audience doesn't understand it. If nothing else, start by writing a summary of the point, and then keep editing it down into the minimum number of words possible. If you can get it down to three or four words, you'll have an effective title. More importantly, you'll have personal clarity.

After you know the point of each bucket, look at all three and how they relate to each other and—most importantly—how they relate to the overarching point and purpose of the speech. Do the buckets flow from one to the next? Do they work together to accomplish your speech's purpose? A great point that distracts from the main point is not a good point.

A great point that distracts from the main point is not a good point.

Does this feel like a lot of work? It's a lot less work to find these problems now rather than in the final draft. And it's even worse to realize, halfway through giving your presentation, that one point is completely irrelevant. Believe me.

Once you know the point of each bucket, you'll be able to sort through material in each with one simple question: Does this explain or support my point? If not, toss it. If you can't bear getting rid of it, move it to Unsorted. Now, you can organize the remaining material within each bucket. Here are some possible structures: (Note: Some of these are also useful for organizing your buckets within the larger speech.)

- Problem/Solution/Testimony

- Problem/False solution/True solution

- Theory/Evidence/Action

- Concept/Explanation

- Mystery/Answer

- Idea/Illustration

- Strengths/Weaknesses/Opportunities & Threats

- Past/Present/Future

- Finances/Operations/Personnel

- Need/Product/The Ask

Play with these ideas, and see what fits your situation the best but always remember to stay focused on the point of the bucket. How will each thing you say enforce the point? By the way, this is one of the great strengths of the bucket system. When (not if) you realize mid‐speech that you forget to say something, it won't really matter. So long as they remember the bucket, it's a win.

Once you're comfortable with your speech's organization, put it on pause and move on to the next step. We'll refine it in step six, giving your subconscious more time to work on it.

4. Write the Conclusion

I call this landing the plane. Done right, your conclusion will summarize your key points, give your audience clear direction for their next steps, and motivate them to go out and do it. Done wrong, it will undo everything you did right in the rest of the speech. No one cares how good the flight was if the plane crashes on landing. A good conclusion has (can you guess?) three components:

a. The Summary

Finish your last point, pause to signal a transition, recap the three points (without adding any new information!), then give a well‐crafted “this is the big idea” statement.

b. The Outcome

Present the desired outcome from your speech. What are the audience's next steps? This could be for them to

- … know something (educational presentations, lectures, lessons, etc.),

- … do something (motivational speeches, action‐oriented sermons, instruction), or

- . . . feel something (toasts, ceremonies, inspirational speeches).

c. The Closing

Finish your speech strong, with one or two well‐crafted sentences that are delivered confidently and with purpose. When you are done, you are done. Don't ruin a perfect landing by adding another mini‐flight.

5. Write the Introduction

As I said at the beginning of this chapter, the introduction is the single most important part of the speech. It is your one opportunity to convince your audience to entrust you with their time and attention. In my experience, you have this much time:

- Eight seconds to give a good first impression.

- Two minutes to capture attention.

- Five minutes to give them a reason to listen to the body.

These are the three phases of the opening, each leading to the next, with the single purpose of preparing your audience to listen to the body of the speech with the highest level of receptivity.

a. First Impression

Eight seconds is roughly the time it takes to walk to the front and say your first sentence (or for you to say your first words coming off of mute on Zoom). By that point, your audience will have already made an initial judgment about you, which is driven primarily by whatever they discern about your identity (another reason we spent so much time on that). Audiences can sense if someone is insecure, disingenuous, or self‐serving. If you're speaking to people who already know you, they'll already have an impression of you, making your first sentence even more crucial for setting the tone.

That to say, your first sentence is a precious commodity, so don't waste it on things like introducing yourself or thanking the emcee: These can be woven into a later part of the speech. Instead, craft a powerful hook, and let that be the first words they hear from you. How do you create a great hook? Read on.

b. Capture Attention

We talk about the honeymoon period to describe the time in any new partnership—a marriage, a new CEO, a new employee—when everyone gives each other the benefit of the doubt. Every speech or presentation is a type of partnership. The audience and speaker are working together for the imparting of ideas, and the audience will typically give you no more than two minutes to demonstrate that you'll live up to your end of the bargain.

The goal in this phase is to hook your audience and create interest by reeling them into the next phase, cementing their impression of you, and laying the foundation for the body of the speech. That last part is crucial. Too many speakers waste their first impression with an irrelevant anecdote. This wastes time and erodes trust.

For that reason, it's vital not to waste time with throat‐clearing—a writing term for unproductive words. Instead, jump right into a killer hook. I've discovered that there are five primary hooks, each of which can be used in one of three different “modes,” yielding fifteen different high‐impact ways to capture attention. The three modes are:

- Being Relatable

This says, “I'm like you, and my material is relevant to you” and is especially valuable when there is an apparent distance (such as age or education) between you and the audience that you want to bridge.

- Being Funny

This says, “I'm likable, and my material is interesting” and is especially valuable when you want your audience to drop their guard and entertain your ideas.

- Being Unexpected

This says, “I'm an interesting person, and my material will engage you” and is especially valuable when your audience (1) has low expectations of you or your speech or (2) is already on information overload, such as at a trade conference.

As you read through the following five hooks, think about how each of them can be used in a relatable, funny, or unexpected mode.

- Question: Starting immediately with a question or series of questions will force the listeners to mentally engage with you.

- Quote: A strong opening quote can invoke the authority of another while holding it at a distance from yourself.

- Statement: A well‐crafted opening statement is like a quote except that it comes from the speaker. This may lessen its authority but shows you're taking full responsibility for the idea.

- Statistic: Used well (and sparingly), statistics can quickly and authoritatively convey a need.

- Story: Stories can be the most labor‐intensive to craft but are also the most effective for bypassing the head and going straight for the heart.

Were you able to think of how each hook could be used in each mode? Test yourself by going to an exercise at connect.mikeacker.com and connecting the fifteen opening sentences with their hook/mode.

As you craft the introduction, take note that the connection between your hook and point doesn't need to be immediately apparent. We've all heard great speeches where we didn't fully understand the opening until the conclusion.

c. Reason to Listen

The final phase of the introduction is to give your audience a reason to listen. The good news is that you already have this, assuming you “started with the questions” (step one of the system). The fourth question was “Why should they care?” All you are doing in this phase is answering this.

Carnegie called it arousing an eager want. I describe it as “painting the pain.” Your job is to make your audience realize how badly they want something and then promising to give it to them. Of course, the term “pain” is relative. If you're giving a wedding toast, the pain may be no more than teasing them with the promise of a really embarrassing story about the groom. In any case, if your introduction can promise a solution to well‐painted pain, you'll have fully engaged audience. But don't deliver the solution (yet). Like any good cliffhanger, you want to leave them dangling for a little while.

If your introduction can promise (but not yet deliver) a solution to well‐painted pain, you'll have a fully engaged audience.

6. Edit for Flow

The final step, editing, is the easiest in some ways and the hardest in others. It's the easiest because the uncertainty has been removed. The pieces are in place; now all that is left is grunt work. It's the hardest because now it's time to start reading out loud, which you've probably been avoiding. But I can't overemphasize how important this is. Things that look wonderful on paper just don't work the same when spoken. This is the step where you transform the vision in your head into reality. I like to read through my speeches in three separate stages.

a. Read and Reinforce

In the first read‐through, ask, “What's missing?” Don't worry about transitions between ideas; that happens in the next stage. Here you're asking if you've said everything you need to say. Are your points clear? Do they need more illustrations or evidence? The more thorough your mind mapping was, the less work you'll have here.

b. Read and Revise

Get more critical in this read‐through. Examine each point and ask if there's a better way to say it. Always look for ways to make it clearer and shorter. Make sure everything flows in a logical order, and experiment with moving pieces around.

This is the time to examine your transitions. Does each item flow naturally from one to the next? Utilize the KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid) principle here and don't make transitions any more complicated than necessary. Sometimes they can be as simple as a pause (between sub‐points) or a one‐sentence summary of a main point.

c. Read and Refine

This is the fine‐tuning read‐through. Look for any rough edges, anything that catches you as you speak it out loud. Better to fix it now than stumble mid‐speech. This stage can be particularly painful because, 95% of the time, you'll have to cut material. The question is not “Is everything here good?” but “Does everything contribute uniquely to the point I want to make?” If you have two great stories that basically say the same thing, keep the better of the two.

If you haven't already timed your speech, do so now. If you tend to talk fast and stick to your notes, assume your speech will go shorter than you think. If you tend to expand on your outline or ramble, assume it will go longer. The results may mean you need to add or subtract more material.

When are you done editing? When you feel that (1) the main point is clear and the speech accomplishes its purpose, (2) no crucial material is missing, and (3) you can give it to yourself in a mirror comfortably. Don't stop until all those are in place.

7. (Optional) Create a Visual Presentation

If your speech calls for a visual presentation (such as PowerPoint, Slide Deck, etc.), treat it as a part of the speech, not an afterthought and not as the first act. Speak through your visual presentation, not around it. I cover this more in Speak and Meet Virtually, but you want to make sure that your presentation enhances your message and doesn't distract from it. I've also discovered that creating the presentation often improves my speech. Writing a slide with a main point, for instance, forces me to refine its wording.

Speak through your visual presentation, not around it.

____________

As I said at the beginning, this is the standard speech system and is the foundation for all the other ones. In the next chapter, we'll explore systems for speaking when you are unable to prepare.

Notes

- 1. Write to Speak was written over two years ago, and I've continued refining my system. For that reason, there are differences in how I now describe the system here, but the framework is the same.

- 2. “John Cleese on Creativity in Management,” https:///www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pb5oIIPO62g