Chapter 1

Emotional Intelligence: The New Science of Success

Jimmy's mom glanced at his report card and frowned. “Look at these grades! Do you realize that this is going into your permanent school record?” The dreaded parental warning played over and over again in Jimmy's 10-year-old mind.” Have I really just blown my opportunity to be successful in life?” he wondered.

Do you recall your school report cards? If you attended grammar school before the 1980s you likely would not have received quarterly progress updates via the electronic, computer-generated version so familiar today. Certainly grades for each course were issued, but they were handwritten in black, blue, or red ink. The long journey home from school even found some youngsters frantically trying to find the right color ink, so that the C in Social Studies could be converted into a B, or possibly even an A. Of course the hope was to avoid whatever the inevitable punishment was going to be for achieving grades lower than expected. Unfortunately, these report cards contained something much more difficult for these children to deal with, something that no one could change or avoid—the teacher's comments scrawled in the margins of the report.

Who knew then, that the most important predictor of young Jimmy's success had little to do with the grade itself, but was more a factor of those handwritten notes in the margin?

Jimmy plays well with all the students and is the most popular boy in school. He is a natural leader. Unfortunately, he is using his popularity to influence other children to stay late on the playground during lunch, instead of coming to math class on time. His grade in math has slipped to a “C.”

If Jimmy was slightly more precocious and allowed to get away with it, he could turn to his parents and say, “Did you know that getting along well with others is a component of emotional intelligence, which research shows is more important for success than my 4th grade math scores?”

Unfortunately, Jimmy can't quite pull that off, and his low grade in math may lead him to be grounded from playing with his friends for a few days. The truth is that the life skills Jimmy learns on the playground are just as important as his academic training in helping him to successfully achieve his goals and get what he wants out of life. When Jimmy is older and enters the workforce, he will discover that a basic level of technical skill and academic achievement are necessary to get his “foot in the door.” He will realize that in some ways school never ends. All employees are expected to develop expertise by learning and improving on the job. But beyond these basic, threshold requirements, the crucial skills that are necessary for his achievement and success are all related to emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1998):

![]() listening and oral communication

listening and oral communication

![]() adaptability and creative responses to setbacks and obstacles

adaptability and creative responses to setbacks and obstacles

![]() personal management, confidence, motivation to work toward goals, a sense of wanting to develop one's career and take pride in accomplishments

personal management, confidence, motivation to work toward goals, a sense of wanting to develop one's career and take pride in accomplishments

![]() group and interpersonal effectiveness, cooperation, and teamwork; ability to negotiate disagreements

group and interpersonal effectiveness, cooperation, and teamwork; ability to negotiate disagreements

![]() effectiveness in the organization, wanting to make a contribution, leadership potential.

effectiveness in the organization, wanting to make a contribution, leadership potential.

Daniel Goleman (1998), who has conducted studies in over 200 large companies, says: “The research shows that for jobs of all kinds, emotional intelligence is twice as important an ingredient of outstanding performance as ability and technical skill combined. The higher you go in the organization, the more important these qualities are for success. When it comes to leadership, they are almost everything.”

Emotional intelligence then, is the x-factor that separates average performers from outstanding performers. It separates those who know themselves well and take personal responsibility for their actions from those who lack self-awareness and repeat the same mistakes over and over. It separates those who can manage their emotions and motivate themselves from those who are overwhelmed by their emotions and let their emotional impulses control their behaviors. It separates those who are good at connecting with others and creating positive relationships from those who seem insensitive and uncaring. It separates those who build rapport, have influence, and collaborate effectively with others from those who are demanding, lack empathy, and are therefore difficult to work with. Above all, emotional intelligence separates those who are successful at managing their emotional energy and navigating through life from those who find themselves in emotional wreckage, derailed, and sometimes even disqualified from the path to success.

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE: THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SUCCESS AND DERAILMENT

Two stories will be presented. One ends successfully; the other does not. Both of these stories represent emotionally charged situations in which the primary difference between one's success and the other's derailment is emotional intelligence. In each situation, emotional arousal offers two possible outcomes:

Success = Being aware of your emotions and managing them so your behaviors are intelligently and proactively driven, resulting in intentional and successful outcomes.

Derailment = Losing control of your emotions so your behaviors are impulsively and reactively driven, resulting in unintended and potentially costly outcomes.

A Success Story

Sarah was 22 years old and had somewhat limited business experience. She was now living on her own, so finding a job (and a source of income) was very important to her. After a series of four interviews for an inside sales and customer service position with a new company, she finally got the call that offered her the position. In her own words she describes the experience:

“I was very excited! This was a new industry in an area of computer technology I was unfamiliar with. It would be an exciting new challenge. Five days before my official start date, I unexpectedly received a plane ticket in the mail from the CEO of the company. I contacted him and asked what it was regarding and was told he would like me to go to Washington, D.C., and assist him with selling the company's computer software at a major tradeshow.

“Initially, I was taken aback with the proposition. I had never met the CEO. I hadn't yet set foot in the office to do even a minute of training. I had no idea how to sell software I had never seen…much less fly to D.C. and sell it there!

“I was nervous. My emotions were telling me to figure out some way to avoid this trip. My gut feeling, however, told me that my decision to go on this trip as requested would set the tone for the rest of my career with this company. It would also establish the CEO's perception of me. Despite feeling scared and quite unprepared for this role, I determined to make the best of it and told the CEO I would be happy to assist him.

“I only had four days to get ready and did not even own a decent business suit. I was on a very limited budget, so I went to a thrift shop to look for an appropriate business outfit. I found the perfect suit. Then I went to the dollar store and found some fake jewelry that looked real enough. I put it all together and managed to look very professional for less than $15.

“When the big day arrived, I flew to D.C. Taking my first taxi ever, I headed downtown to one of the most upscale hotels in Washington. Feeling way out of my league, I checked in and called the CEO to let him know I had arrived. We met at a restaurant in the lobby of the hotel. He was tall and dressed perfectly. My impression was that he set high standards for how he expected others to look. He was professional, friendly, and extremely intelligent. I could tell immediately that he had a low tolerance for incompetence.

“We had a nice dinner meeting, but he offered little in the way of training or information about what I was expected to do. As our dinner ended, he handed me a folder that contained information about the products I would be selling the next morning. It was 11 p.m. I was exhausted and had to go right to bed without time to look over the materials.

“The show started at 7:30 a.m. and I was up at 5 a.m. to give myself enough time to get ready. With little time to spare, I propped up the papers he gave me in front of the bathroom mirror and managed to study the materials while blow-drying my hair! I did the best I could to learn about the software and its features, compatibility issues, technical support solutions, and other details. I relieved some of my nervousness by reminding myself that the CEO would be there to work with me.

“When we met in the tradeshow hall, there were several thousand professionals ready to ask us questions. As it turned out, there would be no “us.” The CEO said I would have to run the show on my own because he had to attend meetings all day. In that moment, I actually wanted to cry! I had no idea what I was doing, and these people all wanted answers. “By about mid-morning, I began to feel more confident. My crash course with hairdryer in hand turned out to be very helpful. Most of the tradeshow attendees showed understanding if I didn't have an exact answer to their questions, and accepted my offer to follow-up with them later.

“At the end of the day when my new boss came back, I was full of smiles. I was proud of myself for all of the accomplishments—arriving, quickly learning the job, and actually selling some software! He inquired, “How did it go?” “Excellent,” I replied. “I did great and we made a lot of money!” His face lit up and he was eager to hear the details. I told him that I sold a $200 piece of software. His face formed a funny smile, the way a parent smiles when a child does something wrong but is too cute to reprimand.

“Now, 10 years later with the same company, I know that $200 for a day is a terrible show. The goal is about $5,000 a day. But in my blissfully ignorant excitement, the CEO was too nice to burst my bubble. It was the foundation for a wonderful 10 years at his company. I am now Director of Operations and oversee a multimillion-dollar business.

“I learned many lessons from that experience in Washington, D.C. Perhaps the most important being that no matter who you are, stretching outside your comfort zone is a formula for success and confidence. Even if I had failed (which in terms of sales numbers I did), I would always be proud that I got on the plane and with a positive, optimistic attitude tried my best! Doing so then and since has ultimately led to a level of achievement I had only imagined.”

A Derailment Story

Ron Artest Jr. was born and raised in the largest public housing development in the United States, the Queensbridge Projects of Long Island City, New York. His success in basketball provided him with his ticket out of the projects. After becoming an NCAA All-American in 1999, he joined the professional ranks, and by 2004, was considered one of the best defensive players in the National Basketball Association. In fact, he was voted the NBA's Defensive Player of the Year for the 2003-2004 basketball season. Unfortunately for Artest, his on-court success has often been be overshadowed by his reputation for having a short fuse.

On November 19, 2004, Artest took center stage in arguably the most infamous brawl in professional sports history. With less than a minute left in the game, Artest's Indianapolis Pacers were well on their way to victory with an insurmountable 97-82 lead over the Detroit Pistons. The brawl began when Artest fouled Piston's Ben Wallace. A frustrated Wallace, upset at being fouled so hard when the game was effectively over, responded by shoving Artest hard with both hands, accidentally hitting him in the nose. A number of Pacers and Pistons squared off, but Artest actually walked away from the fracas and lay on the scorer's table in order to calm himself down. At this point cooler heads could have prevailed, but Wallace continued to instigate. He walked over to the scorer's table and threw his armband at Artest. One of the Piston's fans followed suit by throwing a cup full of ice and liquid that hit Artest on the chest and in the face.

One could argue that Artest was provoked. In his own words, Artest said: “I…was lying down when I got hit with a liquid, ice and glass container on my chest and on my face. After that it was self defense.” In self-defense mode, Artest snapped to attention and jumped into the front-row seats, confronting the man he believed to be responsible. But in the chaos of the moment, he actually confronted the wrong man. The situation quickly erupted into a brawl between Piston's fans and several of the Indiana Pacer players. Artest returned to the basketball court, where he managed to deck a Piston's fan, who apparently was taunting him. The mayhem ended with Detroit fans throwing chairs, food, and other debris at the Indianapolis players while they walked back to their locker room.

In the aftermath, each participant could easily replay the blow-by-blow details that explained and even provoked each successive act of aggression. A flagrant foul provoked a push, a soda-and-ice shower, and some name-calling. A push, a soda-and-ice shower, and some name-calling provoked a brawl in the stands and a fan getting punched. Maybe on some level of playground justice, everybody got what he deserved; perhaps all of the impulsive, uncontrolled emotional behaviors should cancel each other out. After all, it is much easier to critique the actions of others than it is to actually do the right thing in the heat of battle. In moments of honesty we all must admit times when our emotions have unraveled us. It hardly seems fair to single out one player or fan's lack of self-control as being more egregious than the next.

The NBA, however, has rules, and the brawl became a classic case of two wrongs do not make a right. Players are expected to use emotional self-control and rational behavior to maintain the immutable boundary that separates the fans from the court. Given this expectation, the list of guilty participants was indeed extensive. But when the penalties were finally doled out, Artest's penalty was the most severe because of his past history of losing control. He was suspended for 73 games plus playoff appearances, the longest nondrug- or gambling-related suspension in NBA history. NBA Commissioner, David Stern, administered the penalty, stating: “I did not strike from my mind the fact that Ron Artest had been suspended on previous conditions for loss of self-control.”

Regardless of how harsh or unfair this penalty may seem, it serves as a poignant reminder to those who are interested in the field of emotional intelligence. Unmanaged emotional behaviors can be very costly and can derail you from fulfilling your true intentions.

Not only did Ron Artest confront the wrong guy, at the wrong time, and in the wrong way, but that one impulsive act turned out to be tremendously costly. Financially, the suspension cost him $5 million in salary as well as potential endorsement earnings. Emotionally, the suspension cost him an opportunity to compete for a possible NBA championship with a team that might have made it to the finals.

In our success story, Sarah not only recognized the affect that her feelings of anxiety, fear, and insecurity were having on her, but she also managed these emotions in a way that helped her to gain confidence as well as valuable experience in her new job. Had anxiety taken control, she might have missed her flight, offered excuses, pretended that there was a death in her family, or created any number of other reasons for avoiding the very thing that she needed to do in order to be successful.

In our derailment story, Ron Artest actually did recognize that he was agitated and tried to manage his emotions by resting on the scorer's table. This worked until a fan threw a drink on him. Artest defended his actions by claiming self-defense, but there is one significant flaw to this argument—being hit in the face with a cold liquid is not really a severe threat. In fact, many coaches can testify that they have safelysurvived being doused by an entire bucket of ice-cold liquid. There was actually a lesson to learn from this incident and a much more emotionally intelligent way for Artest to have handled this situation. He could have continued to manage his anger and then ask security personnel to escort the offender out of the stadium. Perhaps this alone would have been sufficient to satisfy his anger, but if his anger required even more justice, then he still had the option of pressing charges in a court of law.

There are at least two significant differences between these two stories. First, it is more difficult to manage your emotions when someone is deliberately hostile or offensive as opposed to when someone is simply challenging you to step outside of your comfort zone. Second, there will always be a healthy debate about how ethically right or wrong it is to lose control of your emotions in certain situations. In fact, there is often understanding, not punishment, when you lose control of your emotions because a projectile is thrown at you. At any rate, this book is not concerned with either difference. In other words, it makes sense to live your life in an emotionally intelligent way: No matter how intensely difficult it may be to manage your emotions in certain situations, and no matter how justified you believe it is to lose control of your emotions in certain situations.

Out-of-control emotions can have a tremendous affect on your performance, on how others perceive you, and on how those in power ultimately judge you. The more successful outcome is accomplished when emotional intelligence is applied. This book, then, is all about understanding how to develop into a more fully emotionally intelligent person. In the coming chapters we will guide you through an exploration of the important competencies that are reflected in all emotionally intelligent behavior.

COMPONENTS OF EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

Describing an emotionally intelligent person is like describing a wonderful teacher, an effective counselor, or a successful politician. An entire range of qualities, skills, and behaviors need to be delineated to fully comprehend what the individual is really all about. After all, emotional intelligence, like teaching, politics, or counseling, is a way of being. Concise definitions are possible, but not adequate. We have concisely defined emotional intelligence as:

Using your emotions intelligently to gain the performance you wish to see within yourself and to achieve interpersonal effectiveness with others.

This definition is sufficient as a starting point for understanding EI, as long as one places special emphasis on each component of the definition. Emotional intelligence therefore is

![]() Using your emotions—implies both awareness of and the ability to manage your emotions.

Using your emotions—implies both awareness of and the ability to manage your emotions.

![]() Using your emotions intelligently—implies that you can consciously reflect on your emotions and then choose appropriate responses.

Using your emotions intelligently—implies that you can consciously reflect on your emotions and then choose appropriate responses.

![]() To gain the performance you wish to see within yourself—implies that our emotional energy can serve a special purpose in both motivating and helping us to achieve our goals.

To gain the performance you wish to see within yourself—implies that our emotional energy can serve a special purpose in both motivating and helping us to achieve our goals.

![]() To achieve interpersonal effectiveness with others—implies that our intelligence and sensitivity about emotions can help us achieve better results when relating to others.

To achieve interpersonal effectiveness with others—implies that our intelligence and sensitivity about emotions can help us achieve better results when relating to others.

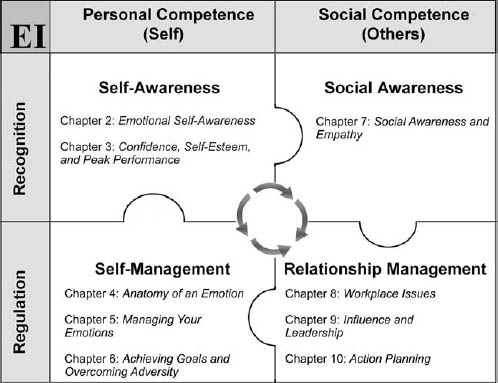

There is both a personal and interpersonal or social component to emotional intelligence. Daniel Goleman, Richard Boyatzis, and Annie McKee (2002) have introduced a model for understanding emotional intelligence that divides personal and social competence into four basic domains. The first two domains are self-awareness and self-management. These domains relate to personal competence. The second two domains are social awareness and relationship management. These domains relate to social competence. According to this model, each domain contains a set of behaviors that can be developed in order for one to become more emotionally intelligent (see Figure 1-1).

UNDERSTANDING AND GROWING YOUR OWN EI

This four-domain model of understanding emotional intelligence will serve as a basic framework for how emotional intelligence is discussed in this book. Each chapter provides a topic that aligns with one of these four domains. At the end of each chapter is a section entitled EQuip Yourself, which includes strategies, applications, and exercises designed to further your development and growth.

Figure 1-1. Goleman, Boyatzis, and McKee's four domains of emotional intelligence; each domain contains a set of emotional competencies.

These four domains of emotional intelligence do not stand alone, independent of one another. Rather, they are interdependent, fitting together like puzzle pieces to present a complete portrait of what an emotionally intelligent person looks like. Emotional intelligence is therefore a comprehensive model that is used to understand how cognitions and emotions affect both personal and interpersonal behaviors. The development of emotional intelligence requires an integration of the competencies and behaviors that make up each domain of this model (see Figure 1-2). As you read this book, many of the examples and illustrations will demonstrate how the integration of all four domains is necessary to achieve an emotionally intelligent whole.

Figure 1-2. The framework for understanding emotional intelligence.

Self-awareness affects self-management and social awareness; self-management and social awareness affect relationship management.