Chapter 4

The Business Analyst’s Facilitation Toolkit

In This Chapter:

Group Analysis Skills

Group Communication Skills

Group Process Skills

Brad Spangler specifies the skills required of an effective facilitator:1

Facilitators must have a variety of skills and techniques to be effective. Strong verbal and analytical skills are essential. Facilitators must know what questions to ask, when to ask them, and how questions should be structured to get good answers without defensiveness. Facilitators must know how to probe for more information when the initial answers are not sufficient. They must also know how to rephrase or “reframe” statements to enhance understanding, and to highlight areas of agreement and disagreement as they develop.

Other skills include redirecting questions and comments, giving positive reinforcement, encouraging contrasting views, including quieter members of the group, and dealing with domineering or hostile participants. Nonverbal techniques include things such as eye contact, attentiveness, facial expressions, body language, enthusiasm, and maintaining a positive outlook. A facilitator must also develop the ability to read and analyze group dynamics on the spot in order to guide the group in a productive way.

According to Miranda Duncan, effective meeting facilitation requires skill in three areas:2

Analysis

Analysis Separating content from process

Separating content from process Identifying interests

Identifying interests Framing problems or opportunities

Framing problems or opportunities

Communication

Communication Choice of words

Choice of words Ability to listen, summarize, and reframe

Ability to listen, summarize, and reframe Using questions to stimulate thinking and control the process

Using questions to stimulate thinking and control the process

Group process models

Group process models Group leadership

Group leadership Decision-making and consensus-building

Decision-making and consensus-building Keeping the meeting on track

Keeping the meeting on track

The remaining sections of this chapter explore the facilitation skills required to successfully perform as a competent business analyst and suggest using the most-often-used tools and techniques to apply when facilitating groups.

Group Analysis Skills

Before making decisions, the group almost always needs to conduct a certain amount of analysis. The business analyst as facilitator leads the group through a process to define the problem or opportunity at hand, identify options, determine criteria by which to evaluate the effectiveness of each option, apply the criteria to each option, and step back and look at the data. Only after discussing the pros and cons of each option should the group make a decision. Until the group performs the analysis, it should not focus on or commit to any specific plan of action on the content. The business analyst as facilitator encourages the group to understand and separate the process from the content and prompts the group to determine the process to analyze the business problem or opportunity first and then move on to the goal or content issues. Analyzing involves:

Separating content from process

Separating content from process Identifying interests

Identifying interests Framing problems or opportunities

Framing problems or opportunities

Separating Content from Process

As previously noted, it is imperative for the business analyst to fully understand the art and power of facilitation so as to remain objective and not unduly influence the group’s decisions. The skilled facilitator focuses on what the meeting is about, the subject or issue at hand, and analysis of the content. In the business analyst’s world, the content of a typical requirements elicitation meeting is the definition of the business need and the process is how the business analyst works with the group to define the business need accurately and analyze it completely. The business analyst provides opportunities for content experts to present information and influence group decisions. The subject matter expert likely uses a presentation style to impart his expertise. Conversely, the business analyst likely uses a facilitating style to confirm and validate the information and to seek input from others as to their perspectives. There is a distinct dichotomy between a presentation leadership style and a facilitating leadership style, as demonstrated in Table 4-1.3

Table 4-1—Presentation Style versus Facilitating Style

| Presentation Style | Facilitating Style |

| Mostly one-way communication | Multiple-way communication |

| Presentation format | Participation format |

| Tell-and-sell approach | Problem-solving approach |

| Ideas presented and defended | Ideas generated by group members |

| Suitable for passing on information | Suitable for productive group work |

| Limits on group creativity | Maximization of group creativity |

Identifying Interests

Another critical analytic skill is the ability to recognize an underlying interest and bring it out into the open so it can be discussed and negotiated. For instance, a key subject matter expert (SME) might not want to discuss a particular agenda item with the full group, claiming it is an unnecessary drain on time and resources. The underlying interest, however, might be that the SME does not want to be embarrassed by his lack of progress on the issue. The facilitator should respect the validity of the SME’s reluctance to push forward with the discussion by asking questions such as: “How can we involve the members of the requirements definition team without the meeting degrading?” Once group analysis techniques are put into place to prevent his being discredited, the SME will be quite willing to involve the team in the analysis and decision as to how to move forward.

Framing Problems or Opportunities

Business problems and opportunities must be stated clearly and analyzed sufficiently prior to drafting requirements for the business solution. The problem/opportunity statement is worded without bias so that participants with differing viewpoints accept the description.

Framing business problems. If the project has been commissioned to solve a business problem, steps typically include the following:

Document the problem in as much detail as possible.

Determine the adverse impacts the problem is causing within the organization; quantify the impacts in terms of lost revenue, inefficiencies, etc.

Determine the immediacy of the resolution and the cost of doing nothing.

Conduct root cause analysis to determine the underlying source of the issues.

Determine the potential areas of analysis required to address the issues.

Draft a requirements statement describing the business need for a solution.

Framing business opportunities. If the project has been commissioned to take advantage of a new business opportunity, steps typically include the following:

Define the opportunity in as much detail as possible; include the events that led up to the discovery of the opportunity and the business benefits expected if the opportunity is pursued.

Quantify the expected benefits in terms of increased revenue, reduced costs, etc.

Determine the immediacy of the resolution and the cost of doing nothing.

Identify the opportunity cost of pursuing this opportunity versus another being considered.

Determine the approach to be undertaken to complete the analysis required to understand the viability of the opportunity.

Draft a requirements statement describing the business need for a solution.

Analysis Techniques

As the business analyst facilitates the group in defining business problems and opportunities and presenting, describing, analyzing, refining, and validating the requirements under consideration, several tools and techniques are commonly used, including:

Facilitated discussions

Facilitated discussions Presentations

Presentations Break-out groups

Break-out groups Flip charts

Flip charts Storyboards

Storyboards Gap analysis

Gap analysis SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis

SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis

Facilitated Discussions

The power of the facilitator lies in the ability to draw out the knowledge and expertise of participants, encourage creativity and innovation, and drive the group to the best decision using the skills presented here. Typical guidelines to facilitate effective discussions include:4

Prepare for the discussion

Prepare for the discussion Open the discussion

Open the discussion Listen intently

Listen intently Ask for clarification

Ask for clarification Manage participation

Manage participation Summarize the discussion

Summarize the discussion Manage time

Manage time Corral digressions

Corral digressions Close the discussion

Close the discussion

Presentations

As we have discovered, presentations are typically one-way communication. They are, however, essential to the group process to level set the group. Persons within the group that have less information than others feel at a disadvantage and, as a result, might shut down. The facilitator plans the use of presentations delivered by selected subject matter experts carefully. The meeting will begin to degrade if presentations are too lengthy or mired in detail. Be sure to allow time for a facilitated discussion after the presentation for the group to process the information and understand its relevance to the meeting objectives.

In addition, the business analyst might be called upon to give presentations on the status of the requirements activities. Giving an effective presentation can often determine the level of continued support for the effort. The business analyst may present requirement status to the project team, the project sponsor, members of management, or members of the customer group. To create an effective presentation, the business analyst would be wise to follow the steps below. Be brief and concise, and remember the Golden Rule: tell them what you are going to tell them, tell them, and summarize what you have told them.5

Assess listener needs.

Write a clear purpose of the presentation.

Develop three or four main points.

Create visuals.

Organize the sequence.

Develop an introduction.

Write a summary and conclusions.

Break-Out Groups

When planning large meetings and workshops, the business analyst should consider using break-out groups for small teams to work together, capture their ideas on their own flip charts, and report back to the full group of participants. If you have all the break-out groups work on the same issue or question, you will see themes emerge from the different groups during the out-brief, thus revealing the consensus thinking of the group. If you have the break-out groups work on different issues and have concurrent work going on, you can quickly gather information on several different topics. During the break-out group out-briefs, be sure to facilitate a discussion and capture the additional thinking of the entire group.

Flip Charts

Skilled use of this low-tech tool is perhaps the most essential business analysis skill. There is power in the act of recording a person’s idea and allowing the group to ask questions for clarity, refine the idea for improvement, and build on it to add value and creativity to the concept. As this process ensues, the idea becomes owned by the group, not only its originator. As ideas are captured on flip charts and posted around the room, the participants begin to see how productive they have been, which is motivating and energizing.

The flip chart information serves as the output of the meeting. After the meeting, the business analyst works with the meeting scribe to capture all the information created by the team into the first iteration of requirements documentation. Here are some simple suggestions for using flip charts effectively:

Learn to write legibly and neatly across the paper (lined paper helps); print rather than writing in cursive.

Learn to write legibly and neatly across the paper (lined paper helps); print rather than writing in cursive. Use color to help distinguish between ideas.

Use color to help distinguish between ideas. Number ideas for ease of discussion.

Number ideas for ease of discussion. Use the sticky type of flip chart paper to avoid having to use tape to post the flip chart sheets on the wall.

Use the sticky type of flip chart paper to avoid having to use tape to post the flip chart sheets on the wall. Listen carefully to the idea being presented, summarize it in a brief phrase, and ask the originator if what you have recorded accurately describes the idea.

Listen carefully to the idea being presented, summarize it in a brief phrase, and ask the originator if what you have recorded accurately describes the idea. Once you have captured the idea to the satisfaction of the originator, ask the group for questions, comments, and recommendations; encourage the group to add to the idea.

Once you have captured the idea to the satisfaction of the originator, ask the group for questions, comments, and recommendations; encourage the group to add to the idea. Do not change the verbiage of the idea presented without the originator’s permission because doing so might alter the intended meaning.

Do not change the verbiage of the idea presented without the originator’s permission because doing so might alter the intended meaning. Ask questions for clarity if you do not understand the idea (if you don’t understand it, others are likely to be confused as well).

Ask questions for clarity if you do not understand the idea (if you don’t understand it, others are likely to be confused as well).

Storyboards

Storyboards are an effective way to document group work in a manner that is easily followed and graphically interesting. A storyboard is a series of panels used to depict elements of a project or process. Initially developed by Walt Disney Studios, storyboards are used extensively in the film industry to depict scenes, copy, and shots for commercials and movies. They are also used extensively in the engineering arena to accompany project proposals. The project manager often uses storyboards as a series of diagrams and text to show how a project to develop a new business solution will look.

The business analyst could use the storyboard in two ways. The first is to describe the steps in the requirements elicitation, analysis, specification, documentation, and validation processes, using one box for each major activity. Each box would contain some text explaining the purpose of the activity, measures of success, deliverables, and schedule, and would be accompanied by a graphical depiction of the process, output, or both (see Figure 4-1 for an example). The second use of storyboards is as a powerful communication tool during requirement review meetings, providing a visual summary of business requirements captured to date. Storyboards might indeed become the first iteration of requirements documentation. Tips for creating a storyboard can be seen in Table 4-2, and a sample storyboard can be seen in Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1—Example of a Storyboard

Table 4-2—Tips for Creating a Storyboard

| Do | Don’t |

| Keep the text brief | Use long or complex verbiage |

| Use lots of visuals | Make the visuals too complex |

| Construct the storyboard in a flowchart style accompanied by a sequence of boxed information | Make the storyboard too long |

| Make sure each box represents a major step in the business function or process | Get too detailed with the first iteration |

Gap Analysis

The gap analysis is a valuable business analysis tool. A gap analysis can be used to:

Benchmark or otherwise assess general expectation of performance in industry, compared with current organizational capabilities.

Benchmark or otherwise assess general expectation of performance in industry, compared with current organizational capabilities. Determine, document, and evaluate the variance or distance between the current and desired future business process.

Determine, document, and evaluate the variance or distance between the current and desired future business process. Determine, document, and approve the variance between business requirements and system capabilities in terms of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) packaged application features (also referred to as a deficiency assessment).

Determine, document, and approve the variance between business requirements and system capabilities in terms of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) packaged application features (also referred to as a deficiency assessment). Discover discrepancies between two or more sets of diagrams.

Discover discrepancies between two or more sets of diagrams. Analyze the gap between requirements that are met and those not met (again, referred to as a deficiency assessment).

Analyze the gap between requirements that are met and those not met (again, referred to as a deficiency assessment). Compare actual performance against potential performance, and then determine the areas that need improvement.

Compare actual performance against potential performance, and then determine the areas that need improvement.

The steps to conduct a gap analysis are typically:

Describe the current state of the business process undergoing change. This is often accomplished by developing a storyboard, a process flowchart, or a workflow diagram.

Describe the future state of the business process.

Compare the current state with the future state.

Document the changes (gaps) needed to get from the current to the future state.

SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis is a valuable tool to quickly analyze various aspects of the current state of the business process undergoing change. The steps are as follows:

Draw a grid similar to the one in Figure 4-2.

Describe the issue or problem under discussion at the top of the grid.

Conduct a brainstorming session (described in detail later in this chapter) to complete each section in the grid.

Facilitate a discussion to analyze the results. Remember that the group has identified only potential characteristics of the problem. Further analysis is needed to validate the actual characteristics, ideally confirmed with data.

Once the characteristics of the issue or problem have been validated, the group brainstorms potential solutions to solve the problem.

Figure 4-2—SWOT Chart

Force Field Analysis

Force field analysis is a powerful tool used by a facilitator to identify and address driving and restraining factors when solving a problem or implementing organizational change. Once a team has selected an option, this tool focuses the team on implementation issues. Typically, the business analyst facilitates a brainstorming session to identify forces that will help or hinder implementing the selected option. After this list is generated, the business analyst combines like ideas, prioritizes them, and develops actions to deal with key forces. To develop the force field analysis:

Write the idea (problem or planned change) on a flip chart or white board.

Draw two columns below the idea; label the left column “driving forces” and the right column “restraining forces,” similar to the sample shown in Figure 4-3.

Brainstorm forces in each column; encourage creativity.

Determine which restraining forces could be removed or weakened and which driving forces can be strengthened.

Figure 4-3—Force Field Analysis Diagram

Force field diagrams can also be used to list pros and cons, strengths and weaknesses, what is known and what is unknown, and perceptions of parties in conflict and to compare the current and target situations.

Root Cause Analysis

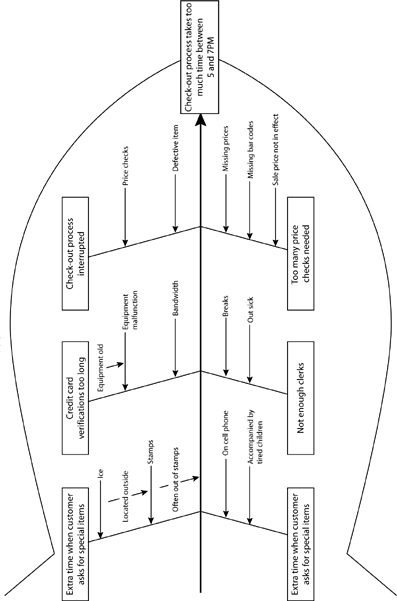

Root cause analysis uses a structured process to identify a problem, gather information, identify and chart root causes, generate recommendations, and develop an action plan to take corrective action. Two techniques are most commonly used, the cause-and-effect diagram, also referred to as the Ishikawa or fishbone diagram, and the five whys.

When using a team approach to problem solving, it is helpful to capture the team’s brainstorming on root causes visually. A cause-and-effect diagram is used to identify and organize the possible causes of a problem. This tool helps the group to focus on the cause of the problem instead of the solution. The technique organizes ideas for further analysis. The diagram serves as a map depicting possible cause-and-effect relationships (refer to Figure 4-4 for an example of a cause-and-effect diagram). Steps to develop a cause-and-effect diagram include:

Capture the issue or problem under discussion in a box at the top of the diagram.

Draw a line from the box across the paper or white board (forming the spine of the fishbone).

Draw diagonal lines from the spine to represent categories of potential causes of the problem. The categories may include people, process, tools, and policies.

Draw smaller lines to represent deeper causes.

Brainstorm categories and potential causes of the problem and capture them under the appropriate category.

Analyze the results. Remember that the group has identified only potential causes of the problem. Further analysis is needed to validate the actual cause, ideally with data.

Brainstorm potential solutions once the actual cause has been identified.

Figure 4-4—Cause-and-Effect Diagram

The five whys approach repeatedly asks questions in an attempt to get to the root cause of the problem. The five whys is one of the simplest facilitation tools to use when problems have a human interaction component. To use this technique:

Write the problem on a flip chart or white board.

Ask “Why do you think this problem occurs?” and capture the idea below the problem.

Ask “Why?” again and capture that idea below the first idea.

Continue with Step 3 until you are convinced the actual root cause has been identified. This may take more or less than five questions.

The five whys can be used alone or as part of the fishbone diagram technique. After all ideas are captured in the diagram, use the five whys approach to drill down to the root causes.

Group Communication Skills

Communication skills are discussed in detail in numerous books and papers. Refer to From Analyst to Leader: Elevating the Role of the Business Analyst for a detailed discussion of communication skills. In this book we focus on the following important business analysis communication techniques that are used when leading discussions:

Choose words carefully.

Choose words carefully. Listen, summarize, and reframe.

Listen, summarize, and reframe. Ask pointed questions.

Ask pointed questions.

Choose Words Carefully

It is important for the business analyst to be knowledgeable about the culture and politics of the organization. In some groups, unfortunate words, so-called red-letter words, can cause powerful emotions because of past occurrences. The business analyst can use certain strategies to avoid inciting negative feelings due to an unfortunate choice of wording:

Familiarize yourself with the business and technical areas as much as possible.

Familiarize yourself with the business and technical areas as much as possible. Ask questions and patiently listen for the entire answer.

Ask questions and patiently listen for the entire answer. Actively seek input from the participants.

Actively seek input from the participants. Encourage questions and different opinions.

Encourage questions and different opinions. Reframe and restate information, choosing your wording carefully.

Reframe and restate information, choosing your wording carefully. Refrain from changing the words the participants used unless the words are ambiguous.

Refrain from changing the words the participants used unless the words are ambiguous. Encourage participants to take ownership of issues, ambiguities, problems, and selection of the appropriate terminology.

Encourage participants to take ownership of issues, ambiguities, problems, and selection of the appropriate terminology.

Listen, Summarize, and Reframe

To ensure that effective communication is occurring, the business analyst predominantly relies on listening intently, summarizing, restating, and asking questions to progressively elaborate requirements. As the discussion unfolds, the business analyst replays the message back to the group for clarity and understanding and captures the key points on a flip chart for all to see, review, and refine. Referring to the flip chart, the business analyst summarizes the discussion that has occurred thus far, asks for approval of the wording, and encourages the group to move on. This technique is particularly useful when the group begins to digress. Alternatively, the business analyst can ask someone in the group to summarize. Then the group moves on to the next planned agenda item or activity.

Ask Pointed Questions

The value of asking pointed questions during meetings cannot be overstated. For the business analyst to become skilled at asking good questions, she must be well acquainted with both the business domain and the technical nomenclature used in the organization.

According to Duncan, asking leading and challenging questions is the most powerful facilitation technique for controlling the discussion and stimulating innovation. Duncan writes that a well-formed question is invaluable because it:6

Signals progress by showing that the group is launching into its agenda: “Shall we begin?” “What do you hope to walk away with by the end of the meeting?”

Signals progress by showing that the group is launching into its agenda: “Shall we begin?” “What do you hope to walk away with by the end of the meeting?” Brings the discussion back on track: “Shall we add that topic to the agenda for next time?” “Do we need to make sure we cover the other items before we run out of time?” Or, “Do we need to decide this in order to decide that?” Questions can provide closure: “Is there anything else before we move on?” “What are our next steps?”

Brings the discussion back on track: “Shall we add that topic to the agenda for next time?” “Do we need to make sure we cover the other items before we run out of time?” Or, “Do we need to decide this in order to decide that?” Questions can provide closure: “Is there anything else before we move on?” “What are our next steps?” Stimulates thinking and rethinking. Statements can be perceived as, or actually are, challenges provoking a counter-challenge or assertion of a superior idea. Questions, on the other hand, create a temporary vacuum—a time for reflection.

Stimulates thinking and rethinking. Statements can be perceived as, or actually are, challenges provoking a counter-challenge or assertion of a superior idea. Questions, on the other hand, create a temporary vacuum—a time for reflection. Eliminates much of the superfluous posturing and maintains an air of openness, an attitude of, “Let me hear more before I decide.” Examples: “If you do this, what will happen?” “Could you describe the process of communication you currently use?” “If you could change one thing about this requirement, what would it be?” In other words, questions, rather than directives or advice, are the most potent way to encourage the group to focus on something, rethink a course of action, or evaluate options.

Eliminates much of the superfluous posturing and maintains an air of openness, an attitude of, “Let me hear more before I decide.” Examples: “If you do this, what will happen?” “Could you describe the process of communication you currently use?” “If you could change one thing about this requirement, what would it be?” In other words, questions, rather than directives or advice, are the most potent way to encourage the group to focus on something, rethink a course of action, or evaluate options.

Questions are structured to accomplish a specific goal. The business analyst may formulate a question to define the scope of the problem, gather data about the problem, and finally begin to draft requirements to solve the problem. Questions are also used to assess an issue or to plan the approach to the discussion. Questions not only promote participation from everyone equally but also manage the discussion. Facilitators often use questions to resolve group dysfunctions, identify the true problem, uncover hidden agendas, and finally drive to consensus. The expert facilitator selects the questioning technique depending on the situation:

Probing questions to dive deeper into an idea

Probing questions to dive deeper into an idea Floating ideas to encourage brainstorming and innovation

Floating ideas to encourage brainstorming and innovation Prompting to push an idea further—to think it through

Prompting to push an idea further—to think it through Summarizing or reframing a concept to reinforce the idea and ensure a common understanding

Summarizing or reframing a concept to reinforce the idea and ensure a common understanding Redirecting the conversation to bring the group back on track

Redirecting the conversation to bring the group back on track Focusing questions, also to bring the group back to the agenda item under review

Focusing questions, also to bring the group back to the agenda item under review Facilitating commitment and ensuring that consensus has been reached

Facilitating commitment and ensuring that consensus has been reached

Table 4-3 presents a few tips for using questions to control the meeting discussion and drive the group to consensus.

Table 4-3—Tips to Control Meeting Discussion

| Do | Don’t |

| Test controversial questions on some participants in advance | Ask the foolish question to get the answer you want |

| Ask open-ended and context-free questions | Ask questions that avoid the true issue |

| Begin with broad questions to establish the topic and ask follow-up questions to narrow the topic | Ask questions that are not aligned with the meeting objectives |

| Plan in advance the questions to be asked for each topic | Ask questions that put participants on the defensive |

| Plan questions appropriate for your audience | Direct questions to the participants that are dominating the meeting |

Group Process Skills

Group process skills are an invaluable asset that professional facilitators bring to meetings. As we have discussed, productive meetings require structure and attention to process. We will examine the role of the facilitator in the following essential group process activities:

Group leadership

Group leadership Group decision-making

Group decision-making Group focus: keeping the meeting on track

Group focus: keeping the meeting on track

Group Leadership

Facilitating groups through effective meetings involves motivating the group by encouraging maximum involvement of all participants. The effective meeting facilitator knows the difference between controlling a group and facilitating a group. Fran Rees clearly states the business analyst’s goals when facilitating requirements elicitation and validation meetings: “The goal is not to gain power but to complete the work assigned to the team. The goal is not to divide power into definable pieces but to work together to produce what could not be produced by individuals working alone.”7

Team Facilitation

The business analyst’s facilitation role is different from that of an external professional facilitator brought into an organization to facilitate a single meeting. The external facilitator attempts to understand the audience but is not focused on the development of the team’s maturity. On the other hand, the business analyst works as an integral part of a project team throughout the business solution life cycle (BSLC). In this role, the business analyst is well suited to assist the project leadership team in becoming a high-performing team, as discussed in the previous chapter. In addition, the savvy business analyst will alter her facilitation style based on the current state of the group.

Team Leadership

An understanding of the importance of team leadership skills for business analysts is emerging. It is now considered appropriate for the business analyst to only be aware of the technical area of the project, not to be the technical expert. The business analyst’s project focus is on business, rather than technical, objectives. The business analyst understands that projects are technical solutions to business problems that are solved with human intervention and collaboration. Behavioral, people skills are now considered vital for project success.

To complement the team development model presented in the previous chapter, David C. Kolb, Ph.D., offers a five-stage team development model.8 The value of the model is that it describes the ideal facilitator style for each stage of team development. The facilitator learns to adopt a certain role to maximize team effectiveness. Kolb contends that a group facilitator subtly alters her style of meeting facilitation depending on the group’s composition and level of maturity. While continually using basic facilitation skills, the business analyst complements them with mediation, coaching, consulting, and collaborating styles to lead discussions as needed. The experienced facilitator moves seamlessly between these facilitation modes as she observes and diagnoses the team’s performance. The business analyst needs to work to acquire all the team leadership roles mentioned in Table 4-4 and, more important, to know when and how to apply them, because teams dynamically move in and out of development phases during the life of the project. To learn more details about the Kolb model, refer to From Analyst to Leader: Elevating the Role of the Business Analyst, another book in this series.

Table 4-4—Five-Stage Team Development Model

| Development Phase | Facilitator Role |

| Building | Facilitator |

| Learning | Mediator |

| Trusting | Coach |

| Working | Consultant |

| Flowing | Collaborator |

Group Decision-Making

Virtually all group participants will be most familiar and comfortable with making decisions by voting. Voting is appropriate to some situations but is almost never appropriate in the business environment, where decisions are made on the basis of business value to the enterprise as a whole. This is because of the all or nothing, win/lose outcome of decisions by voting. So, when is it appropriate for a facilitator to make decisions based on a vote? Only when the facilitator finds herself in the situation where there has been ample dialogue; the participants are large in number, diverse, and geographically dispersed; and time is of the essence and it is imperative to make a decision and move on.

Several decision-making options are depicted in Table 4-5. Selecting the appropriate approach will make the decision-making process more likely to succeed.

Table 4-5—Decision-Making Options

| Decision Type | Appropriate When |

| Total agreement |

|

| Assigned decision |

|

| Voting |

|

| Compromise |

|

| Consensus |

|

Consensus Decision-Making

Consensus decision-making is the most-often-used approach for teams defining requirements. Clearly, in a business environment where decisions should be made based on business value to the enterprise as a whole, the facilitator’s job is to drive the group to consensus. There is a great deal of confusion about what consensus decision-making is and what it is not. Consensus is reached when debate has taken place, the interests of all participants have been considered, and a decision has been made and will be supported by everyone.

Consensus does not mean that the decision is necessarily everyone’s first choice. It does mean that everyone can live with it and commits to supporting it. If the decision did not come easily, the facilitator probes further by explaining that if anyone still has reservations about the decision, she has the responsibility to raise the issue to the group for further discussion before the final decision is made and the discussion is closed. In effect, everyone has veto power and should use it until she can truly support the decision in the future. Consensus means that all considerations have been discussed and resolved. For very important decisions, the facilitator polls the group one by one, posing the question: “Can you live with it and will you support it?”

Consensus decision-making is difficult for newly formed teams, the members of which have not yet begun to trust one another. The skilled facilitator, however, uses the consensus-building process to unite the group, uncover various perspectives, and foster a collaborative approach to decisions to improve buy-in. When making decisions, use the consensus approach when a large number of stakeholders sense that they are positively or negatively affected by the decision. Be sure to allow adequate time for discussion to understand various perspectives and positions on the problem, and to resolve valid concerns. When consensus cannot be met, the facilitator must determine the next best way to handle the decision from among other alternatives. In most cases, if consensus was required, the facilitator escalates the issue to the next level of management for resolution. Presented in Table 4-6 are a few tips for making decisions by consensus.

Table 4-6—Consensus Decision-Making

Once the decision is made, the facilitator moves quickly to action. Implementation strategies include:

Assign an owner or person responsible for acting on the decision.

Assign an owner or person responsible for acting on the decision. Identify activities and tasks that will support the decision, and work with the project manager to identify resource requirements, timelines, and associated costs.

Identify activities and tasks that will support the decision, and work with the project manager to identify resource requirements, timelines, and associated costs. Determine whether there are any communication or training requirements during the implementation of the decision.

Determine whether there are any communication or training requirements during the implementation of the decision.

Decision-Making Tools and Techniques

Depending on the type of meeting, effective tools can bring about the best group decision to solve a problem or identify the best alternative. Most of these are used during informal working sessions and formal workshops.

Surveys

Distributing a quick questionnaire about the issue to relevant stakeholders often helps to uncover facts and opinions. This technique is useful when there is a significant amount of unknown information. A survey can gather important information quickly. To help drive to the decision, ask questions such as:

What are the differing opinions?

What are the differing opinions? Who is involved or affected?

Who is involved or affected? Why does the issue exist?

Why does the issue exist? When does the decision need to be made?

When does the decision need to be made? What are the possible options or alternatives?

What are the possible options or alternatives? Are there any unrepresented views? Was someone not included in the meeting?

Are there any unrepresented views? Was someone not included in the meeting?

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is perhaps the most-often-used facilitation technique. Brainstorming is a technique for generating a list of ideas about an issue. It promotes innovation, creativity, and out-of-the-box thinking. Before teams make a decision, they should make sure they have examined as broad a range of options as possible. Brainstorming is an easy, enjoyable, and effective way to generate a list of ideas. It truly is a “group brain dump.” This is the process business analysts use most often to promote team involvement, so learn to do it well.

Brainstorming is used to generate lists of problems, issues, ideas, solutions, and items. The facilitator works to make the session quick and enjoyable, generate excitement, and stimulate involvement. A successful brainstorming session lets people be as imaginative as possible and does not restrict creativity in any way. This technique is used to equalize participant involvement. It often results in original solutions to problems. Refer to another volume in this series, Unearthing Business Requirements: Elicitation Tools and Techniques, for additional information about brainstorming.

Brainstorming Guidelines

Encourage everyone to get into the spirit. Don’t hold back on any ideas, even if they seem silly at the time; the more ideas the better.

Encourage everyone to get into the spirit. Don’t hold back on any ideas, even if they seem silly at the time; the more ideas the better. Do not allow any discussion during the brainstorming session. Explain that there will be time for discussion later; the goal now is to identify as many ideas as possible.

Do not allow any discussion during the brainstorming session. Explain that there will be time for discussion later; the goal now is to identify as many ideas as possible. No judgment is allowed. No one is allowed to criticize another person’s ideas—not even with a groan or a grimace. (Note: People don’t usually understand this rule, but it is imperative that no one renders judgment on the ideas as they are presented. Sometimes the wildest idea is the best.)

No judgment is allowed. No one is allowed to criticize another person’s ideas—not even with a groan or a grimace. (Note: People don’t usually understand this rule, but it is imperative that no one renders judgment on the ideas as they are presented. Sometimes the wildest idea is the best.) Encourage people to build on ideas generated by others in the group.

Encourage people to build on ideas generated by others in the group. Write all ideas on a flip chart so the whole group can easily scan them.

Write all ideas on a flip chart so the whole group can easily scan them.

Brainstorming Sequence of Events

Clarify purpose. The facilitator reviews the purpose of the brainstorming session. Write the question on a flip chart or white board, or hand out sheets of paper with the question on them. This way, people can refer back to the question when they want to be reminded of the session’s purpose.

Clarify purpose. The facilitator reviews the purpose of the brainstorming session. Write the question on a flip chart or white board, or hand out sheets of paper with the question on them. This way, people can refer back to the question when they want to be reminded of the session’s purpose. Generate ideas. Give everyone a minute or two of silence to think about ideas. Ask them to jot their ideas down as they come to mind. Ask them to try to think of at least three to five items.

Generate ideas. Give everyone a minute or two of silence to think about ideas. Ask them to jot their ideas down as they come to mind. Ask them to try to think of at least three to five items. List ideas. Go around the room asking each participant for his or her best idea. As you facilitate, enforce the ground rules (“No discussion! Next idea …” Discussion limits creativity.) Write all ideas on the flip chart, or collect and post them if sticky notes are used. Be sure to number each idea. Pause only to check for accuracy. (The scribe may not change the wording unless the presenter agrees.) Encourage participants to build on each other’s ideas. This is when the creativity begins to come into play. Continue until everyone’s list is complete.

List ideas. Go around the room asking each participant for his or her best idea. As you facilitate, enforce the ground rules (“No discussion! Next idea …” Discussion limits creativity.) Write all ideas on the flip chart, or collect and post them if sticky notes are used. Be sure to number each idea. Pause only to check for accuracy. (The scribe may not change the wording unless the presenter agrees.) Encourage participants to build on each other’s ideas. This is when the creativity begins to come into play. Continue until everyone’s list is complete. Clarify and combine. The facilitator asks if anyone has questions of clarity about any items listed. The person who contributed the idea should be the one to answer questions, but others may join in. The wording may be changed for clarification but only when the person who originally proposed the idea agrees. See if ideas can be combined. Renumber, assigning the same number to like ideas. Ask the members of the group to write down the numbers of the items they would like addressed or selected. Tally the votes. You may do this by letting members vote by a show of hands as each item number is called out, or ask the participants to use markers and put checkmarks beside their top three choices.

Clarify and combine. The facilitator asks if anyone has questions of clarity about any items listed. The person who contributed the idea should be the one to answer questions, but others may join in. The wording may be changed for clarification but only when the person who originally proposed the idea agrees. See if ideas can be combined. Renumber, assigning the same number to like ideas. Ask the members of the group to write down the numbers of the items they would like addressed or selected. Tally the votes. You may do this by letting members vote by a show of hands as each item number is called out, or ask the participants to use markers and put checkmarks beside their top three choices. Prioritize. To reduce the list, eliminate the items with the fewest votes. The objective is to get no more than five to eight ideas. The rule of thumb is this: if it is a small group (5 or fewer members), cross off items with only 1 or 2 votes; if it is a medium group (6 to 15), eliminate anything with 3 or fewer votes; if it is large group (more than 15), eliminate items with 4 votes or fewer.

Prioritize. To reduce the list, eliminate the items with the fewest votes. The objective is to get no more than five to eight ideas. The rule of thumb is this: if it is a small group (5 or fewer members), cross off items with only 1 or 2 votes; if it is a medium group (6 to 15), eliminate anything with 3 or fewer votes; if it is large group (more than 15), eliminate items with 4 votes or fewer. Discuss and refine. If time allows, you may discuss and refine the wording of the remaining ideas. Be sure to be clear what the next steps will be: What are we now going to do with the prioritized list of ideas?

Discuss and refine. If time allows, you may discuss and refine the wording of the remaining ideas. Be sure to be clear what the next steps will be: What are we now going to do with the prioritized list of ideas?

Brainstorming Variations

Brainwriting. Brainwriting, also referred to as the knowledge café, is a tool for small groups to brainstorm and build on each other’s ideas. The business analyst should use this technique to add energy to the group, accommodate large groups, and allow more time for thinking than the typical brainstorming session allows. Using a form or flip chart, groups of five or six people each write three ideas. Then they pass the forms around for other participants to add their ideas. This method generates many ideas in a short time.

Brainwriting. Brainwriting, also referred to as the knowledge café, is a tool for small groups to brainstorm and build on each other’s ideas. The business analyst should use this technique to add energy to the group, accommodate large groups, and allow more time for thinking than the typical brainstorming session allows. Using a form or flip chart, groups of five or six people each write three ideas. Then they pass the forms around for other participants to add their ideas. This method generates many ideas in a short time. Anonymous brainstorming. In this brainstorming technique, participants anonymously write their ideas on a piece of paper. The papers are tossed into a box and drawn out one by one for the team to discuss. No names or group affiliations are identified to keep anonymity and encourage discovery and discussion by all participants.

Anonymous brainstorming. In this brainstorming technique, participants anonymously write their ideas on a piece of paper. The papers are tossed into a box and drawn out one by one for the team to discuss. No names or group affiliations are identified to keep anonymity and encourage discovery and discussion by all participants. Idea mapping. A facilitator uses this graphical tool to identify affected areas, dependencies, and issues related to the problem being solved. See Figure 4-5 for an example of idea mapping.

Idea mapping. A facilitator uses this graphical tool to identify affected areas, dependencies, and issues related to the problem being solved. See Figure 4-5 for an example of idea mapping. 20 Questions. This approach provides the group with a powerful problem-solving strategy. 20 questions is best used when the problem is associated with a single element of a complex system. Referred to as a binary search when it is used to conduct a computerized search, 20 questions is one of the fastest search methods. Lists of items are continually divided in half as yes/no questions are asked. With this tool, a facilitator challenges assumptions and does not directly focus on the cause of the problem.

20 Questions. This approach provides the group with a powerful problem-solving strategy. 20 questions is best used when the problem is associated with a single element of a complex system. Referred to as a binary search when it is used to conduct a computerized search, 20 questions is one of the fastest search methods. Lists of items are continually divided in half as yes/no questions are asked. With this tool, a facilitator challenges assumptions and does not directly focus on the cause of the problem.

Figure 4-5—Idea Mapping

The business analyst builds a list of questions asking if an element of the system can be eliminated as a cause, and begins to ask the questions. Hopefully, half of the alternatives can be eliminated with each question. When most of the potential causes have been eliminated, the business analyst facilitates a discussion to form a hypothesis about what caused the problem. At this point, the fishbone diagram can be used to determine the possible root causes. See Figure 4-6 for an example of the 20 questions technique.

Figure 4-6—Questions

Sequential Questioning. Using this technique, the business analyst initiates a discussion or discovery session by proposing a series of questions. Each question is documented on a flip chart page. The initial questions are written at the big-picture level, followed by subsequent questions that progressively elaborate more detail of the topic. By starting with the big view and decomposing the topic into smaller components, the participants address the topic with a thorough and complete approach.

Sequential Questioning. Using this technique, the business analyst initiates a discussion or discovery session by proposing a series of questions. Each question is documented on a flip chart page. The initial questions are written at the big-picture level, followed by subsequent questions that progressively elaborate more detail of the topic. By starting with the big view and decomposing the topic into smaller components, the participants address the topic with a thorough and complete approach. Affinity Diagram. Affinity diagrams are useful to narrow the discussion because they organize like ideas. They are used when creative or intuitive thinking is required. The sequential questioning technique addresses the issue in a top-down manner, whereas the affinity diagram identifies and organizes ideas from the bottom up, without predetermined restrictions or constraints on the discussion. Groups use this tool to clarify complex issues and reach a consensus on the definition of a problem. It answers a “what” question. For example, it might be used to answer the question “What are the root causes of events that determined or impacted the quality of our product?” Making an affinity diagram can be quite time-consuming, but is a valuable activity. The facilitator involves the entire group in creating an affinity diagram, following these steps:

Affinity Diagram. Affinity diagrams are useful to narrow the discussion because they organize like ideas. They are used when creative or intuitive thinking is required. The sequential questioning technique addresses the issue in a top-down manner, whereas the affinity diagram identifies and organizes ideas from the bottom up, without predetermined restrictions or constraints on the discussion. Groups use this tool to clarify complex issues and reach a consensus on the definition of a problem. It answers a “what” question. For example, it might be used to answer the question “What are the root causes of events that determined or impacted the quality of our product?” Making an affinity diagram can be quite time-consuming, but is a valuable activity. The facilitator involves the entire group in creating an affinity diagram, following these steps:

Gather individuals’ ideas on sticky notes passed up to the front of the room.

Group the notes on the basis of themes.

Label the groups.

Draw the diagram by placing related notes near each other.

Rank categories and combine duplicate issues to create the final, simpler diagram.

Multivoting

Multivoting is a group technique used to prioritize ideas to quickly select the most important or most popular items from a list. It is accomplished through a series of votes, each cutting the list in half. Multivoting often follows a brainstorming session and is used to select the most important items from a list of brainstormed items with limited discussion and difficulty. A list of 30 to 50 items can be reduced to a workable number in 4 or 5 votes. First, count the items and divide by 5 to get the number of possible votes per team member. The facilitator conducts a multivote by following these steps:

Generate a list.

Combine similar items; an affinity chart might be used to eliminate redundancy.

Ask team members to narrow the list by selecting the most important items on the list; allow each participant a number of choices equal to one-fifth of the total number of items.

Tally the votes by asking each participant to put a checkmark by his or her choices.

Eliminate those with few or no votes.

Repeat steps 3 through 5.

The items that remain are candidates for further analysis by the group.

Nominal Group Technique

Nominal group technique (NGT) is a more structured approach than brainstorming or multivoting, but it is similar to both. NGT is a consensus planning technique that helps prioritize ideas. It is referred to as “nominal” because the group doesn’t engage in the usual amount of interaction. It is useful when all or some of the group members are new to the team or when the group is quite large. It is an extremely effective technique for highly controversial issues or when the team seems to be stuck in disagreement. The facilitator conducts an NGT session by following these steps:

Part One: Individual Brainstorm

Part One: Individual BrainstormThe facilitator defines the issue or problem and describes the purpose of the session and the procedures.

After discussion to clarify the issue and the process, each participant is asked to generate and document ideas.

The facilitator then goes around the room and asks each participant to present one idea. The idea is captured on a flipchart. After the first round, participants are asked for a second and third response, until all ideas have been captured.

The facilitator then leads a discussion to clarify and discuss ideas and condenses the list by combining like ideas.

Part Two: Making the Selection

Part Two: Making the SelectionReduce the list by multivoting (see above).

The facilitator asks each participant to individually make selections by writing one item on a card. Limit the number of cards to four to six for each member.

Ask participants to assign points based on the number of index cards (for four cards, assign the number 4 to the most preferred item).

Tally votes and discuss results.

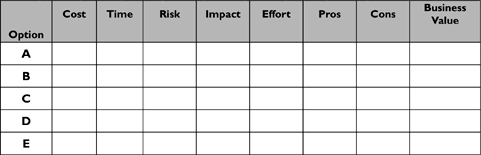

Decision Grids

Decision grids are useful when facilitating a group to examine all possible alternatives that were identified during the brainstorming session prior to making the decision. A sample decision grid appears in Table 4-7. The process for using the grid is as follows:

Define the problem or issue clearly; note on a flip chart.

Brainstorm potential options to resolve the problem or issue (see brainstorming techniques earlier in this chapter).

Describe each option in enough detail so that all participants understand the option.

Facilitate a discussion to complete the information desired about each option. (Be sure to define the criteria to ensure that all participants understand the categories.)

Step back and ask the group which options appear to be the best in terms of lowest time, cost, and risk and highest value to the business.

Table 4-7—Decision Grid

Group Focus—Keeping Meetings on Track

A good facilitator provides the structure and process needed for the participants to work together effectively. The facilitator notices, through verbal and nonverbal cues, when participants are disturbed or bored and have mentally checked out of the meeting. Through experience, the business analyst learns effective meeting facilitation techniques and knows when to intervene, summarize, and move the group on and when to let the discussion continue.

In addition to the facilitation techniques discussed in this chapter, several meeting management techniques are essential to keeping the meeting on track, including those listed in Table 4-8.

Table 4-8—Meeting Management Techniques

| Technique | Description |

| Plan |

|

| Use the agenda |

|

| Start and end on time |

|

| Facilitate | Keep in mind your role as meeting facilitator. Your responsibilities are to:

|

| Keep thediscussionsfocused |

|

| Keep timing appropriate |

|

| Leaddiscussions |

|

| Manage behaviors |

|

| Close the meeting |

|

We will now turn our attention to specific meetings that the business analyst leads during the life of the project. It might appear that we are focusing our attention primarily on the meetings the business analyst conducts during the requirements phase. However, the requirements elicitation, analysis, specification, documentation, and validation activities are not linear; they are very much iterative and occur throughout the project.

For each meeting we provide a description of the meeting, its benefits, its challenges, the participants, the strategy for conducting the meeting, inputs to the meeting, outputs or results of the meeting, and a proposed facilitator agenda. A facilitator agenda differs from a standard meeting agenda in that it provides facilitation suggestions, tools, and techniques to lead the group through each agenda item.

Endnotes

1. Brad Spangler. “Facilitation,” Beyond Intractability, 2003. Online at www.beyondintractability.org/essay/facilitation/ (accessed August 10, 2007).

2. Miranda Duncan. Effective Meeting Facilitation: The Sine Qua Non of Planning. Online at http://arts.endow.gov/resources/Lessons?DUNCAN1.html (accessed October 17, 2006).

3. Fran Rees. How to Lead Work Teams: Facilitation Skills, 2001. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

4. Peter R. Scholtes, Brian L. Joiner, and Barbara J. Streibel. The Team Handbook, 3rd ed., 2003. Madison, WI: Oriel, Inc.

5. Ibid.

6. Miranda Duncan. Effective Meeting Facilitation: The Sine Qua Non of Planning. Online at http://arts.endow.gov/resources/Lessons?DUNCAN1.html (accessed October 17, 2006).

7. Fran Rees. How to Lead Work Teams: Facilitation Skills, 2001. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

8. David C. Kolb. Team Leadership, 1996. Durago, CO: Lore International Institute.