Chapter Two

Strategy Guides Passion

Mythology tells us that the hero Theseus overcame insurmountable challenges, like killing the half-man half-bull monster, Minotaur, and escaping from a mazelike labyrinth with the help of Ariadne, who held the end of a thread at the entrance to the labyrinth. Scholars have offered Ariadne’s actions as a metaphor for what leaders can do to help others escape the labyrinths of their own worlds: keep extensive records, and when you get lost, return to the last point of clarity and safety. Though Ariadne helped Theseus and others with her red yarn, this method will doom today’s leaders to an exhaustive process that merely allows them to solve problems—not make the bold decisions about the company’s future that will position them for growth and success in the new economy.

History has taught us that the prerequisites of success—courageous leadership, bold direction, clear goals, and a systematic approach to implementation—can also provide a recipe for disaster. The reason? Decision-makers must make choices with far-reaching consequences based on assumptions about what that future will look like. Of course, this paradox has always existed—nothing new about an inability to prophesize about the future. But one thing has drastically complicated the landscape: the future arrives much more quickly now than it used to, and many of the guests it tows along are neither invited nor welcome.

Many leaders feel unsure about their ability to create a credible strategy for growth, despite overwhelming evidence that they can—facts that prove that the best strategies come from pragmatic business leaders who are willing and able to consider alternative futures for their businesses. It won’t happen automatically, however. Successful leaders will take a systematic approach in setting the direction for the organization and then develop the day-to-day tactics that will support it—all combining to create the organization’s competitive advantage.

Head in Exceptional Directions

Every organization is headed somewhere. Too often, however, leaders don’t consciously choose that direction. Instead, they react to the environment in which they find themselves. They engage in perceived potential, reactive decision-making, or short-term gains designed to placate shareholders and analysts. They work long hours on daunting tasks—often to no avail—because they haven’t chosen the right race.

In most organizations, you’ll find more people who understand how to run fast than people who can decide which race they should enter, more people with well-honed skills for producing results in the short run than visionary strategists. This happens because they start by questioning “How?” when they should have led with “What?”:

• What will determine the nature and direction of our organization?

• What policies and key decisions will have a major impact on our financial performance?

• What decisions will involve significant irreversible resource commitment?

Visionary leaders understand that to outrun the competition, they will need to understand those things that should remain the same, those that should change, their guiding principles, and their competitive advantage. Only then will they be able to challenge the ordinary. Or, as Peter Drucker taught us years ago, “There is surely nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency what should not be done at all.”1

The Timeless Advantage

Your mission forms the foundation of your timeless advantage. It should play the same role in your organization that the Holy Grail did in the Crusades. It defines your reason for being, the touchstone against which you evaluate your strategy, activities, and expectations for overcoming the competition. Without a mission, you will diffuse resources, cause individual units of the organization to operate in silos, create conflicting tactics, and confuse customers, suppliers, financiers, and employees. A mission statement answers these questions:

• Why do we exist?

• What is our business?

• Who are our customers?

• What do our customers value?

Wal-Mart’s succinct mission statement, “Saving People Money So They Can Live Better,” addressed all four questions, but apparently, judging from the 2012 changes, decision- makers lost the mouse pad that had those words written on it. Executives now acknowledge that they miscalculated and are adjusting their strategy. But at what cost? Analysts have been concerned that in changing direction again, Wal-Mart risked alienating whatever higher-scale shoppers it gained during its transition. In situations like this, sometimes David doesn’t kill the giant; it commits suicide—an unfortunate circumstance caused by deviation from the mission.

Unlike most for-profit organizations, nonprofits are mission-driven. Therefore, they devote a great deal of thought to defining what the mission should be. They avoid sweeping statements full of good intentions and focus, instead, on objectives that have clear-cut implications for the work their members perform. The Salvation Army strives to make citizens of the rejected. The Girl Scouts help girls become confident, capable young women who respect themselves and other people, and Habitat for Humanity gives a hand up, not a hand out. Similarly, nonprofits start with the “customer” foremost in their minds—not financial gain.

Bonds—communities, societies, and those served—hold members together and define success for nonprofits. But task alone characterizes the successful for-profit organization. A symphony orchestra does not attempt to cure the sick; it plays music. The hospital takes care of the sick but does not attempt to play Beethoven. Indeed, as Drucker also noted, “an organization is effective only if it concentrates on one task. Diversification destroys the performance capacity of an organization.” Societies and communities must be multidimensional; they are environments, but an organization is a tool. The more specialized the tool, the greater its capacity to perform its given task.2

The ability and willingness to differentiate your company, product, and services stand squarely at the heart of timelessness. When you build a solid foundation—your version of Theseus’s ship—you’ll preserve the aspects of your organization that define it, while replacing the worn and rotten aspects of it. When you know the difference, you’ll equip yourself and others to leverage your timeless advantage but never at the expense of your transient advantage.

The Transient Advantage: The Just-in-Time Organization

The “just-in-time organization,” a term largely associated with manufacturing, also describes an organization that has learned that speed is paramount—that roughly right decisions must replace accurate but slow ponderings. This type of organization has demonstrated an ability to “turn on a dime” when necessary, without losing sight of the big picture.

Henry Ford introduced the concept of just-in-time more than 90 years ago, but it has gained attention recently because of a general push to more quickly do more with less. Those companies that have adopted or adapted some form of what some call “JIT” have realized predictable benefits. They have kept inventory and the costs associated with it to a bare minimum, they’ve eliminated or drastically reduced waste, and they have consistently produced high-quality products with greater efficiency. But the most significant benefit has been the close relationships the approach has fostered among decision-makers, those in operations, and customers. These relationships obviously exist outside the arena of manufacturing.

The ability to respond to unexpected success can also explain transient advantage. For example, scientists at Allergan, a multi-specialty healthcare company focused on discovering, developing, and commercializing innovative pharmaceuticals, discovered a new market for its product Bimatoprost. These eye drops, originally developed to control the progression of glaucoma, also make eyelashes grow, and Latisse was born.

After seeking and obtaining FDA approval for Latisse, the drug company hired Brooke Shields to advertise the “new” product for an untapped market. Today millions of tiny, expensive bottles of Latisse have landed in the medicine cabinets of women who can afford to pay about $200 a month for darker, longer eyelashes.

Nonprofits too have changed through time as they have built on their transient advantages. For example, RAND, an outgrowth of World War II, was dedicated to furthering and promoting scientific, educational, and charitable purposes for the public welfare and security of the United States. The aftermath of the war revealed the importance of technology research and development for success on the battlefield and the wide range of scientists and academics outside the military that made such development possible.

RAND developed a methodological approach called systems analysis, the objective being “to provide information to military decision-makers that would sharpen their judgment and provide the basis for more informed choices.” As RAND’s agenda evolved, systems analysis served as the methodological basis for social policy planning and analysis across such disparate areas as urban decay, poverty, healthcare, education, and the efficient operation of municipal services such as police protection and fire fighting.

Today, RAND’s work continues to reflect and inform the American agenda. While one part of RAND works to define the emerging epidemic of obesity among Americans, another has presented lessons learned from the military response to Hurricane Katrina that can be applied to future military disaster-response efforts. While one division analyzes standards accountability under No Child Left Behind, another details ways to reduce the terrorist threat from regions with weak governmental control. Across a broad range of subjects, RAND research is characterized by its independence, objectivity, nonpartisanship, high quality, scientific rigor, interdisciplinary approach, empirical foundation, and dedication to improving policymaking on the major issues of the day.3 RAND has not lost sight of its original mission, yet it continues to act as a just-in-time source for analysis and information.

The Seven Secrets for Balancing Timelessness and Transiency

Business authors and theorists have traditionally advised leaders to “stick to the knitting,” whereas other voices have chimed in “turn on a dime.” Obviously, getting the balance right is critical, but how can a business leader harmonize the two voices to create beautiful music?

1. Stay close to the customer. RAND and others serve as shining examples of what can and should happen when business leaders listen to and heed the advice of their best customers—not all customers, just the best ones. Anticipate their needs, feel their pain, and devise the solution before they need it. No one told Steve Jobs what to invent or what the “next best thing” would be.

2. Develop an EOC orientation. Strategists often refer to VOC or Voice of the Customer. While the VOC remains important, the EOC, or Eye of the Customer, also plays an important role. Proactive decision-makers look at the world through their customers’ eyes. Latisse would quite literally have lost its competitive advantage if they had not looked through the eye of the customer.

3. Reward entrepreneurial behavior. Recognize individuals at all levels of the organization, and listen to their feedback.

4. Have an exit strategy for products, customers, and services that no longer support both your timeless and transient advantages.

5. Budget quickly. Don’t tie yourself to a one-to-three-year strategy that relies on budget decisions that may have to change. Instead, budget quarterly, and assign control of money decisions to a disinterested group or individual that doesn’t run a division or business. Also, don’t set up a “spend before the end of the fiscal year or you won’t get it next year” mentality. Reward those who return money.

6. Put your smartest people in charge of risky decisions. The smartest, not necessarily the hardest-working, people should make the decisions related to innovation and risk. The last thing you want is an idiot with initiative deciding the future of your business. Balance experimentation, which takes time, with analysis, which happens quickly.

7. Make feedback to senior leaders seamless, fast, and laudatory. Remove roadblocks in the chain of command and replace them with easy access.

We have long taken business advice from business magnate and investor Warren Buffet. Now is the time to weigh that wisdom with country/western singer Jimmy Buffet’s observation that “I didn’t ponder the question too long. I was hungry and went out for a bite.” Only those hungry leaders who can figure out how long to ponder will balance their timeless and transient advantages to use them as the foundation of their strategic principles and competitive advantages.

Turn Your Strategic Principle Into Financial Results

Results start with a strong strategic principle, a shared objective about what the organization wants to accomplish. The strategic principle guides the company’s allocation of scarce resources: money, time, and talent.

The strategic principle doesn’t merely aggregate a collection of objectives. Rather, this simple statement captures the thinking required to build a sustainable competitive advantage that forces trade-offs among competing resources, tests the soundness of particular initiatives, and sets clear boundaries within which decision-makers must operate.

Creating and adhering to a concise, unforgettable action phrase can help everyone keep an eye on the ball at all times. Wal-Mart used its mission statement, “Saving People Money So They Can Live Better,” to develop its strategic principle: “Low prices, every day.” This succinct phrase should have challenged Wal-Mart’s 2012 decision to sell trendy fashions to attract higher-income customers, but it didn’t, and they paid the price for the mistake.

A well-thought-out strategic principle pinpoints the intersection of the organization’s passion, excellence, and profitability, or in the case of not-for-profit organizations, its unique contribution. As you can see from the graphic, success lies at the intersection of the three.

If your organization operates in Section 1, you will probably experience some short-term success, and star performers will find themselves drawn to work for you—initially. People who can do the work they feel passionate about and engage in work that rewards efforts with large monetary compensation can often stay in the game for the short run. But if you aren’t the best—and the clever in your organization will quickly figure out that you aren’t—the competition will soon surpass you.

Passion and excellence without profitability, or Section 2, won’t even allow you a short run. This undisciplined orientation—to do what you like and are good at—without consideration of the market, won’t provide anything other than some short-lived fun, which should last right up until the time your bills come. You won’t find too many virtuosos in these kinds of organizations for very long, if at all.

Section 3 offers a recipe for burn-out. You can work hard at something you’re good at and that makes you significant money, but you won’t excel at it for long unless you feel some passion for it. Star performers don’t dip their professional toes into the water; they show up to make waves. If they don’t feel passion for the work, they won’t do either.

The sustained success of exceptional organizations lies in Section 4, the intersection of passion, excellence, and profitability. These companies have high-quality products and services that consistently encourage them to develop newer and better offerings. Only here can your organization thrive as you work diligently to produce a product or service that your competition can’t match.

When companies face change or turmoil, the strategic principle acts as a beacon that keeps the ships from running aground. It helps maintain consistency, but gives managers the freedom to make decisions that are right for their part of the organization. Even when the leadership changes, or the economic landscape shifts, the strategic principle remains the same. It helps decision-makers know when to develop new practices, products, and markets. When they face a choice, decision-makers will be able to test their options against the strategic principle by simply applying the three-part litmus tests:

1. Are we passionate about this work?

2. Can we do it better than our competitors?

3. Will it make us money?

When designed and executed well, a strategic principle gives people clear direction while inspiring them to be flexible and take risks. It offers a disciplined way to think about decisions, strategy, and execution, and challenges people to play an ever-evolving better game. Top performers embrace both change and risk, but they do their best work when they understand the parameters within which they must work. These allow star performers to act as agents for and champions of change, rather than as mavericks.

Your Competitive Advantage

The mission and strategic principle—both cornerstones for organizations that challenge the ordinary—don’t usually pose the most difficult issues. Threats to the strategy lie not in figuring out what to do, but in devising ways to ensure that, compared to others, you actually do more of what everybody knows you should do—that is, leverage your competitive advantage.

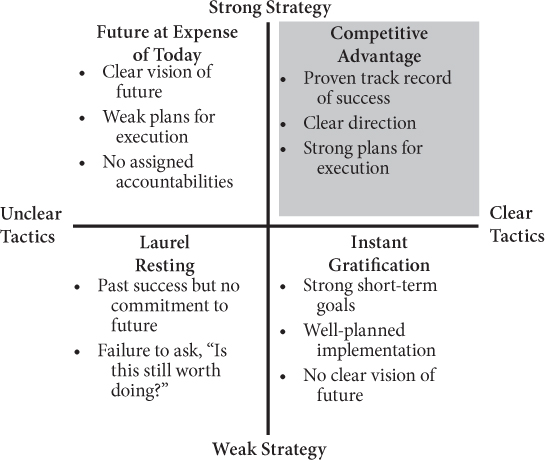

We don’t improve primarily because rewards remain in the future; we experience the disruption, discomfort, and needed discipline more immediately. My work with countless companies has taught me that the necessary outcome of strategy formulation does not involve analytical insight—although it is an indispensable first step: It requires resolve. People have to make up their minds that they want a different future than the one they have and steadfastly commit to making the changes that will bring about that ideal state—that set of circumstances that aligns the strategy with tactics to create your competitive advantage. With this mindset, leaders consciously sacrifice some of the present rewards to achieve a better tomorrow. Drawing from the work of Tregoe, here’s how this balance looks:4

Each quadrant represents desirable or undesirable ways for companies to operate.

The Competitive Advantage quadrant represents an organization that has established a competitive edge that includes a strong strategy and the clear tactics to support it. Based on a proven track record, this company has identified those decisions that have led to success in the past and that promise success in the future. By responding to customer needs, developing talent, implementing effective operations, and defining sound financial objectives, this organization has acknowledged what it must do to beat the competition and has identified ways to implement this strategy.

Companies that operate in this quadrant continuously seek ways to build on their capabilities. Leaders adapt well to change and eagerly experiment with new approaches and novel ideas. They don’t readily settle for “okay,” but instead challenge themselves and others to constant improvement, and they differentiate themselves as the places virtuosos want to work.

A company that has clarified its competitive advantage commits itself to excellence, the foundation of strategy. High-performance organizations that have stood the test of time and promise to continue productivity in the future provide examples of this. When a commitment to excellence exists, passion and profitability often follow.

Organizations operating in the Instant Gratification quadrant often succeed in the short term. Despite current profitability, they lack a strong strategy. They engage in effective operations that have accounted for their success in the past, but success in the future remains doubtful. Often hospitals and manufacturers operate in this quadrant. In the long run, rivals take over, but for a period of time, these companies can stay afloat with hard work. Companies like this frequently offer good products or services and are passionate about what they do, but they lack excellence or profitability.

Members of these organizations frequently resist discussions of strategy because what they’re doing seems to be working. In these situations, I often encounter a significant commitment to lean processes, Six Sigma, or Total Quality Management, all tactics for driving a strategy. The leadership makes solving immediate problems their primary focus, and strategy formulation seems like a distraction from that priority. Investing the time to engage in a strategy formulation process will lead them to fewer wasted hours and distracted efforts in the future, but for an organization accustomed to instant gratification, the future seems too far off and too abstract.

Most failed companies get buried strategically, not tactically. They may have been making the best horse-drawn buggy in the world when they went under. They may have had strong day-to-day tactics, but they picked the wrong direction or chose too many directions simultaneously. In other words, the problem usually doesn’t lie in an inability to produce a quality product or service; it’s knowing what customers will want more of in the future.

The Future at the Expense of Today quadrant depicts a company that has invested the time and energy to write and develop a strong, clear strategy. However, they have failed to formulate the ways they will execute. Some of the high-tech companies and pharmaceutical manufacturers offer examples of how a company might operate in this quadrant. This kind of situation most often occurs when leaders have left the strategy-setting session with no accountabilities for each initiative. When no one has a vested, personal interest in the outcome, you put tactics, execution, and implementation at risk, not to mention your overall success.

The challenge of the leader is to offer a disciplined approach—an intellectual framework to guide decisions and serve as a counterweight to the quick and easy fix of unfettered growth. This requires an examination of which industry changes and customer needs the organization will respond to and which ones it will reject. Deciding which business you will turn away can play as important a role as determining which business you want.

Laurel Resting organizations struggle tremendously. Most of the major airlines fall into this quadrant. At one time they may have had some clear direction, perhaps some strong leadership and committed employees who developed the processes and systems for driving the business. But, for whatever reason, these best practices have eroded. Apparently no one has asked recently, “Is this still worth doing?” Usually companies that operate in this quadrant for very long don’t stay companies for very long.

If your organization is operating in quadrants other than the Competitive Advantage one, you must first rid yourself of the strategies and tactics that no longer produce results, to begin sloughing off the decisions of yesterday in order to make the pivotal ones for tomorrow. And you have to harness the resolve to delay gratification. (Working in the Competitive Advantage quadrant usually hurts in the short run.)

Real strategy lies not in figuring out what to do but in devising ways to ensure that, compared to others, we actually do more of what everybody knows we should do. The single biggest barrier to making change is the feeling that “It’s okay so far.” Too often leaders settle for the status quo—or good—rather than demanding exceptional. These kinds of leaders destine themselves and their organizations to hire good, maybe even very good, performers. But they won’t attract stars. Virtuosos want to play for the best team, not the good one.

Successful strategy cannot be what “most of us, most of the time” do. It has to involve everyone’s commitment to making it happen. You can’t achieve a competitive advantage through things you do reasonably well most of the time. Everyone has to resist the temptations that will steer you off course.

Usually we know what we should do. Figuring out the obvious is not difficult. Doing what needs to be done, however, isn’t always easy. No mysterious cure lurks unnoticed and undiscovered. We all know what we have to do to improve. But the discomfort happens now when we deprive ourselves of the things we want, so we postpone the improvement.5

St. Louis–based Enterprise Rent-A-Car offers one of the most compelling examples of a company leveraging its timeless, transient, and competitive advantages. After World War II, Jack Taylor, a decorated Navy fighter pilot who served on the USS Enterprise, from which today’s company takes its name, returned to his hometown and started his business. He soon discovered that you uncover your best opportunities by listening to your customers.

Jack didn’t set out to build a rental car company. Enterprise began as an automobile leasing business with a different name. Through time, his leasing customers asked for loaner cars while their vehicles were in the shop. Jack began offering daily rentals. From an initial investment of $100,000 and just seven cars, Enterprise has grown to a $15 billion global powerhouse with more than 74,000 employees in more than 7,000 locations. Through the years, Taylor and those that he has hired have stuck to their mission “to fulfill the automotive and commercial truck rental, leasing, car sales, and related needs of our customers and, in doing so, exceed their expectations for service, quality and value.”

How many times did we hear that Hertz was number one but Avis tried harder? Avis attempted to play leapfrog with the unicorn of the rental car business and created no advantage. Enterprise knew better.

Enterprise didn’t try to get you out of the airport faster. That was Hertz territory. Even though they did try harder and give better customer service than all the others, they didn’t tout that. Instead, they told you they would pick you up. But Enterprise might have ignored its current competitive advantage if they had not listened to the employee who suggested the concept.

They became number one in supplying replacement cars to people who have had an accident. Now they have built a successful business by partnering with insurance companies, and by the way, they will also get you out of the airport fast now too. But that isn’t how it all began.

Who is the unicorn in your industry? Are you trying to emulate, duplicate, or imitate it? If so, you will probably always take second place and never discover, much less leverage your transient advantage. Whether you are an independent consultant or an executive in a large organization, my guess is you’ve spent too little time analyzing your unique contribution.

Instead of trying to leap over or chase the competitor in front of them, leaders who have learned to leverage their transient advantage change the game to one they can win. Customer responsiveness explains much of Enterprise’s success, but not all of it. Decision-makers at Enterprise also responded to the voice and eye of the customer because they also listened to a frontline employee who helped steer the company into the rental car business in the first place and a consultant who came up with the idea for its now defining “We’ll Pick You Up” service.6

What can you do that no one else does as well? Who would miss you if you went away? The answers to these questions will give you a sense of your competitive advantage, that which separates you and makes you better. Instead of trying to leap over or chase the competitor in front of you, change the game to one you can win, and then make sure you have a solid plan to decide what has to happen to implement the strategy.

The Feud Between Strategy and Decision-Making

The best leaders get most of the important calls right. They exercise good judgment and make the winning decisions. All other considerations evaporate because, for the most part, at the senior-most echelons of any organization, people won’t judge you by your enthusiasm, good intentions, or willingness to work long hours. They have one criterion for judging you: do you show good judgment? Therefore, leveraging your strengths in this arena and avoiding the hidden traps of individual and group decision-making define two of the surest ways for you to improve in your own decisionmaking and to influence the effectiveness of your team.

When group members make effective decisions, they can do so because they have used time and resources well, resulting in correct, or at least well-thought-out, conclusions that they can easily carry out. Problems, however, can interfere with this process. Here are some to look out for.

The Groupthink Trap

In 1972, social psychologist Irving Janis first identified “groupthink” as a phenomenon that occurs when decision-makers accept proposals without scrutiny, suppress opposing thoughts, or limit analysis and disagreement. Historians often blame groupthink for such fiascoes as Pearl Harbor, the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Vietnam War, the Watergate break-in, and the Challenger disaster. Groupthink, therefore, causes the group to make an incomplete examination of the data and the available options, which can lead the participants to a simplistic solution to a complex problem.

The decision-making that led to the Challenger disaster illustrates how each of these causes of groupthink can lead to a tragic outcome. The Challenger blasted off at an unprecedented low temperature. The day before the disaster, executives at NASA argued about whether the combination of low temperature and O-ring failure would be a problem. The evidence they considered was inconclusive, but more complete data would have pointed to the need to delay the launch.

Cohesion and pressure to conform probably explain two of the primary causes of the groupthink. The scientists at NASA and Morton Thiokol felt the pressure of their bosses and the media to find a way to stick to their schedule. Because the group discouraged dissenters, an illusion of unanimity surfaced, and the collective rationalization that allowed the decision-makers to limit their analysis led to their favoring a particular outcome—to launch on time.

Due to an extraordinary record of success of space flights, the decision-makers developed an illusion of invulnerability, based on a mentality of overconfidence. After all, NASA had not lost an astronaut since the flash fire in the capsule of Apollo 1 in 1967. After that time, NASA had a string of 55 successful missions, including putting a man on the moon. Both NASA scientists and the American people began to believe the decision-makers could do no wrong.7

Any one of the causes of groupthink can sabotage decision-making, but in the case of the Challenger, they created a tragic outcome by displaying most of the symptoms. When you’re in the throes of groupthink, you can’t always see or understand what’s happening. That’s why you need to take steps to prevent it before it rears its ugly head.

The Failure to Frame Trap

When you or your organization faces a significant decision, as the senior leader, one of your primary responsibilities will be to frame the problem for yourself and others. Like a frame around a picture, this can determine how we view a situation and how we interpret it. Often the frame of a picture is not apparent, but it enhances the artwork it surrounds. It calls attention to the piece of work and separates it from the other objects in the room.

Similarly, in decision-making, a frame creates a mental border that encloses a particular aspect of a situation, to outline its key elements and to create a structure for understanding it. Mental frames help us navigate the complex world so we can successfully avoid solving the wrong problem or solving the right problem in the wrong way. Our personal frames form the lenses through which we view the world. Education, experience, expectations, and biases shape and define our frames, just as the collective perceptions of a group’s members will mold theirs.

People who understand the power of framing also know its capacity to exert influence. They have learned that establishing the framework within which others will view the decision is tantamount to determining the outcome. As a senior leader, you have both the right and responsibility to shape outcomes. Even if you can’t eradicate all the distortions ingrained in your thinking and that of others, you can build tests like this into your decision-making process and improve the quality of your choices. Effective framing offers one way to do that.

The Complexity Trap

Too often, people seek unnecessary perfection in the place of pragmatic success. Part of the problem involves an often-unspoken belief that the simple is somehow unintelligent, primitive, or embarrassing. That’s an overly complex view.

Remember Occam’s Razor: The easiest answer is usually the best. I could tell you more, but let’s keep this simple. Effective framing can help you embrace “Occam’s Razor,” a principle attributed to the 14th-century English logician and Franciscan friar that states “Entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily.” The term “razor” refers to the act of shaving away everything that stands in the way of the simplest explanation, making as few assumptions as possible, and eliminating those that make no difference. All things being equal, the simplest solution should win.

The Status Quo Trap

Fear of failure, rejection, change, or loss of control—these often unfounded fears cause decision-makers to consider the wrong kinds of information or to rely too heavily on the status quo. According to psychologists, the reason so many cling to the status quo lies deep within our psyches. In a desire to protect our egos, we resist taking action that may also involve responsibility, blame, and regret. Doing nothing and sticking with the status quo represents a safer course of action. Certainly, the status quo should always be considered a viable option. But adhering to it out of fear will limit your options and compromise effective decision-making.

The Anchoring Trap

A pernicious mental phenomenon related to over-reliance on the status quo, known as “anchoring,” describes the common human tendency to rely too heavily, or to “anchor,” on one piece of information when making decisions. It occurs when people place too much importance on one aspect of an event, causing an error in accurately predicting the feasibility of other options.

According to research, the mind gives disproportionate weight to the first information it receives, to initial impressions, and preliminary value judgments. Then, as we adjust our thinking to account for other elements of the circumstance, we tend to defer to these original reactions. Once someone sets the anchor, we will usually have a bias toward that perception.

Most people are better at relative than at absolute or creative thinking. For instance, if I were to ask you if you think the population of a city is more than 100,000, instead of coming up with a number of your own, your mind will tempt you to use 100,000 as a relative frame of reference.

To avoid falling into the anchoring trap, don’t reveal too much information. Once you give your opinion and shape information, others will tend to defer to your senior leadership position and echo your values and ideas. When this happens, you lose the opportunity to think about the problem from a variety of perspectives.

The Sunk Cost Trap

Adherence to the status quo and anchoring closely align with another decision-making trap: the predisposition not to recognize sunk costs. The sunk-cost fallacy describes the tendency to throw good money after bad. Just because you’ve already spent money or other resources on something, doesn’t mean you should continue spending resources on it. Sometimes the opposite is true, yet because of an illogical attachment to our previous decisions, the more we spend on something, the less we’re willing to let it go, and the more we magnify its merits.

Sunk costs represent unrecoverable past expenditures that should not normally be taken into account when determining whether to continue a project or abandon it, because you cannot recover the costs either way. However, in an attempt to justify past choices, we want to stay the course we once set. Rationally we may realize the sunk costs aren’t relevant to current decision-making, but they prey on our logic and lead us to inappropriate choices.

The Inference and Judgment Trap

Facts are your friends. When you face an unfamiliar or complicated decision, verifiable evidence is your most trusted ally, but also the one many senior leaders reject. Instead of steadfastly pushing for definitive information, they settle for the data others choose to present, seek information that corroborates what they already think, and dismiss information that contradicts their biases or previous experience. When guesswork or probabilities guide your decisions, or you allow them to influence the decisions of others, you fall into the trap of too little information or the wrong kind of information.

Facts are your friend, but they are scarce allies. Inferences and judgments, which can be more influential and pervasive, tend to dominate discussions and drive decisions. To the untrained ear, the inference can present itself convincingly as a fact. Inferences represent the conclusion one deduces, sometimes based on observed information, sometimes not. Often inferences have their origin in fact, but a willingness to go beyond definitive data into the sphere of supposition and conjecture separates the fact from the inference.

Flawed decision-making explains many of the tragic mistakes organizations have made in the name of strategy. In spite of the leadership team’s best efforts at the off-site two-day strategy-setting meeting, the company just doesn’t move forward. Or it moves forward in the wrong direction or at the wrong speed. More often, however, the organization enters the right competition but trips during the race.

Implementation: The Scene of Many Accidents

A breakthrough product, dazzling service, or cutting-edge technology can put you in the game, but only rock-solid implementation of a well-developed strategy can keep you there. You have to be able to deliver—to translate your brilliant strategy and operational decisions into action. Of course it all starts with a clear mission, a strong strategic principle, and a well-formulated strategy that leverages the competitive advantage. Clear strategy leads the process; great performance completes it. If you’re like many executives, however, in an effort to improve performance, too frequently you address the symptoms of dysfunction, not the root causes of it. You focus your attention and that of others on what’s going wrong instead of why it doesn’t work. That explains the problems developers had with the Comet.

Those who led the jet age had clear strategy: both the United States and the United Kingdom wanted to win the race in the sky to offer the first jet service across the Atlantic Ocean. But differences in implementation decided the winner.

Once begun, the competition for dominance in the air progressed quickly. Less than 50 years after the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, Great Britain launched the Comet, the first commercial jet plane; but the glory was fleeting. The revolutionary Comet suffered from a curse—a catastrophic, inexplicable flaw, and an unknown Seattle company put a new competitor in the sky: the Boeing 707 Jet Stratoliner.

The race culminated in October 1958, between two nations, two global airlines, and two rival teams of brilliant engineers. This Anglo-American competition pitted the Comet, flown by the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), against the Boeing 707, flown by Pan American World Airways. Until 1958, more people crossed the Atlantic Ocean aboard ships than on airplanes. Fewer than one in 10 American adults had ever been on an airplane. (Today nine out of 10 adults has flown.)

But the race began well before 1958. In the autumn of 1952, Juan Trippe, the head of Pan American, the dominant U.S. international carrier, decided not to wait for American manufacturers to give him what he wanted. He ordered three British Comets, with an option for seven more. Eddie Rickenbacker, the World War I U. S. flying ace and head of Eastern Airlines, made an even more audacious announcement. He would pay $100 million for 35 Comets, but he wanted all of them by 1956. Fortune magazine called 1953 “the year of the Coronation and the Comet.” Time called the Comet “the new queen of the airways,” but the pronouncements came too soon—seemingly condemning the Comet’s chance to win the race.

In January 1954, the Comet roared down the runway at Rome’s airport and climbed through 26,000 feet. Shortly after, the Comet blew apart, instantly killing everyone on board. Rumor blamed sabotage for the explosion over Italy, but this hadn’t been the Comet’s first brush with disaster. Previously, a Comet had broken apart just six minutes after takeoff from Calcutta’s airport, killing 43 people. Authorities concluded the plane had been taken down by a vicious thunderstorm.

Two other Comets had suffered serious damage in incidents involving pilots struggling with sudden, unexpected rolling of the plane just after takeoff. Yet no one wanted to blame the plane. Soon all seven of the remaining Comets in the BOAC fleet were put back into service. Sixteen days later, another Comet blew apart in the skies over the Tyrrhenian Sea, killing all on board. Sabotage and thunderstorm theories aside, clearly the Comet had a mysterious flaw that speed and ambition—the banes of effective implementation—had caused the designers to overlook.

Even though the Comet later went through arduous revisions, the British aviation industry never fully recovered from the Comet disasters and never regained its jetliner supremacy, its early inroads short-lived. The 707 became the leading plane of the Jet Age, and until the advent of jumbo jets, more than a decade later, the majority of people who crossed oceans did so in a Boeing 707.

Bill Allen, the CEO of Boeing, was smart, ambitious, and systematic in deciding to jump into the jet airliner business. The company decided to pursue military contracts for large, four-engine jet tankers that could provide aerial refueling and cargo services. Consequently, it developed an important advantage: a huge wind tunnel in Seattle that could be used for aerodynamic testing near the speed of sound. Boeing engaged in endless hours of testing on countless variations to find the secrets of successful jets.

Allen courted Pan Am, United, and American presidents. (Eisenhower would end up flying in a 707 as soon as 1959.) Through his methodical leadership approach (he would consistently go around the room of engineers to hear everyone’s perspective), Allen came to the conclusion that would enable the company to demonstrate a prototype jet to the armed services and the commercial airlines in the summer of 1954. Under Allen’s 25-year tenure as its leader and his strict commitment to execution of a clear strategy, Boeing grew from $13.8 million to $3.3 billion.

Historians might also argue that Boeing had a “second-mover advantage,” meaning the second to experiment has the benefit of learning from the first mover’s failures. They could argue, too, that the Comet was the most spectacular aircraft ever built but would have to admit that its failure was equally spectacular—costing more than a hundred lives.8

Clearly, implementation, not strategy, caused British aviation to fail. Strategy formulation involves asking “what?” Execution is a systematic process of rigorously discussing “how?”—questioning, tenaciously following through, and ensuring accountability. It includes linking the organization’s mission, vision, and strategy to execution, creating an action-oriented culture of accountability, connecting the strategy to operations, and robust communication. When you implement effectively, you get smart answers to these questions:

• How do we position products, compared to our competitors?

• How can we translate our plan into specific results?

• How do we consistently monitor both performance and results?

• How can we attract the right kinds of people to execute our plan?

• How can we build strong relationships with our customers and business partners so that they will act as brand ambassadors and challenge us to improve?

• How do we make sure our activities deliver the outcomes to which we’ve committed?

In other words, the heart of implementation lies in three core constructs: strategy, people, and operations. To implement the strategy successfully and get answers to these questions, you’ll need to address all three.

Implementation involves discipline; it requires senior leader involvement; and it should be central to the organization’s culture. Done well, implementation pushes you to decipher your broad-brush theoretical understanding of the strategy into intimate familiarity with how it will work, who will take charge of it, how long it will take, how much it will cost, and how it will affect the organization overall.

My experience has shown that execution fails for one of 10 reasons:

1. Senior leaders never truly commit to the strategy (what needs to happen), so they make decisions on tactics (how things should happen), confusing activity with results.

2. The CEO starts the victory dance on the 20-yard line, glad the team has played the game of formulating the strategy, overlooking the fact that they haven’t actually won the game.

3. No one individual “owns” an objective.

4. Individuals leave the strategy formulation session without a plan for and commitment to a time line for achieving the objectives.

5. People concentrate on contingent (What now?) actions instead of preventive (Don’t let that happen.) actions.

6. Leaders don’t set priorities.

7. Leaders don’t tie rewards and consequences to achievement of objectives.

8. Pressing day-to-day problems trump critical threats to the strategy.

9. Leaders don’t serve as avatars and exemplars.

10. Leaders don’t balance risk and reward.

Conclusion

Strategy discussions have changed since Peter Drucker and those of his ilk began challenging business leaders to think about and lead the direction their companies would take. But the truly important things about strategy have remained the same. Strategy formulation still requires the willingness and ability to make the tough choices about what to do and what not to do. You still need to define where you want to compete, how you intend to win, and how you plan to leverage your advantages—the timeless, transient, competitive, and exceptional advantages that have consistently helped you outrun the competition up until now.

In mythical times, Ariadne enjoyed a proven track record of success. She and only she could save the potentially doomed from her half-brother, the half-bull. But while important things have remained the same since Drucker offered his sage wisdom, much has changed since Ariadne saved her lover, Theseus. We now know that traditional approaches and mere problem-solving won’t be enough, even when you have a goddess working on your behalf.