Business Value-Add: Minimizing the Activities that Reduce Customer Value

You can have big plans, but it’s the small choices that have the greatest power. They draw us toward the future we want to create.

Robert Cooper1

Organizations spend most of their scarce resources in delivering business value-add activities. In this chapter we look at the categories of business value-add in more depth as we learn how to differentiate and categorize activities that are business-, not customer-driven.

Placing Business Value-Add in Context

The reason organizations exist is because the formal combination of talents, skills, and resources into one entity provides superior capability for meeting customer expectations and delivering value to the market more efficiently. Instead of having to enter into market transactions for every activity that needs to be done, an organization brings all of the needed inputs together under one entity. What drives the creation of organizations is the desire to lower transaction costs.

Many different organizational forms arise in the economy. For instance, many firms decide to vertically integrate, buying up their trading partners in the value chain so they can gain control over product features, price, quality, and the timeliness to market. Other firms decide to go “virtual,” focusing on keeping direct control of only core competencies and outsourcing all other activities to other companies in the marketplace. General Electric is an example of a firm that pursues vertical integration, while Nike is known for being one of the top virtual firms in the world.

Whether vertically integrated or virtual, all companies have to deliver the basic functions of being in business—generating invoices (business value-add—indirect), designing future products and services (business value-add—future), and generating the payroll (business value-add—administrative). While some activities simply have to be done in order for the firm to exist, these types of activities do not generate revenue from today’s customers. Business value-add activity costs come directly out of profit.

Even when an activity is inherently value-adding, it contains some form of business value-add and waste. Paperwork abounds, absorbing time and dollars for which the final customer won’t reimburse the firm. Every activity also contains some element of waste—one can always find a better way of performing an activity. This fact drives the continuous improvement movement, one that the VCMS embraces.

Business value-added activities are the ones that should be targeted when the firm is attempting to improve its profitability through process redesign. Since these activities, or portions of activities, come directly out of profit, finding better ways to do them or eliminating them altogether drives profit improvement. However, not all business value-added activities are created equal. They differ in terms of how vital they are to the long-run success of the organization.

BVAI—Indirect Customer Support

Business value-add indirect (BVAI) is a category of activities that indirectly touch the customer. They are not part of the value proposition of the firm, but they are tied to the customer transaction. One of the most common of these activities is the generation of an invoice for an order. The customer expects an invoice, but doesn’t value getting it. On the other hand, if the invoice is incorrect, customers can become dissatisfied with the firm. This dissatisfaction can actually lead to the search for an alternative service or product provider.

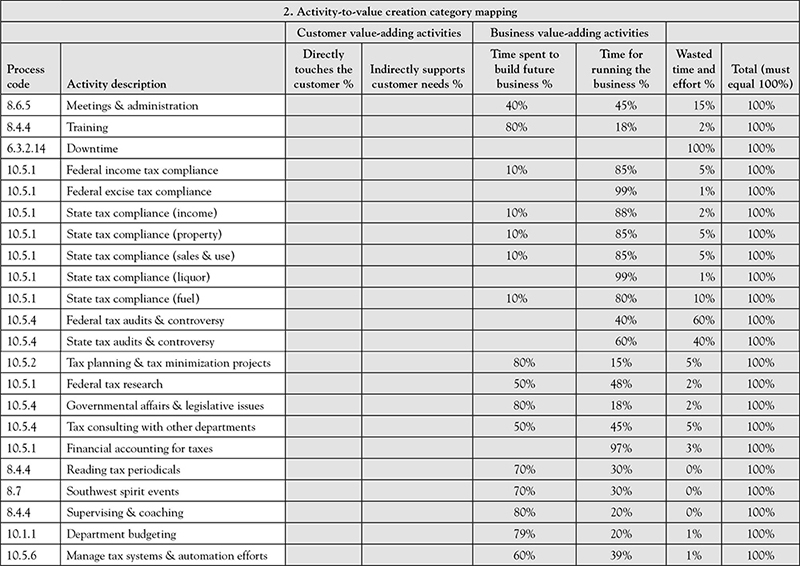

When doing a cost analysis, it is truly amazing how many activities have at least some portion of BVAI embedded in them. Each time the firm completes a “touch” moment with the customer, BVAI actions take place. As seen in Figure 3.1, taken from Easy Air’s research study, a broad range of activities contain some element of BVAI.

Figure 3.1. Business value-add—indirect.

NOTE: Each of the rows should sum to 100% of the available time and effort the activity consumes.

As can be seen from this example of the internal group that establishes meetings and group events, there is some level of customer service provided that is indirect to the customer but essential to the relationship of the firm with its customers. For instance, internal and external communications have no direct customer value-add assigned to it, but is seen as being 20% indirect value-add. The importance of BVAI activities was perceived to be so important that Easy Air decided that it wanted to include BVAI actions in its definition and analysis of value-add in the firm.

Another example of BVAI is daily operations development and maintenance. Clearly the customer would suffer if the airline did not develop daily operational reports that are used to coordinate the timing of flights and the rotation of aircraft to various routes or maintenance. This is essential information for the smooth operations that the customer does benefit from. The customer expects that this work is done, but does not want to pay for it in their purchase transaction.

The splitting of activities across multiple classifications reflects the fact that activities are made up of tasks, or actions, that take place. While an activity can be predominantly business value-add—administrative, for instance, it may contain some tasks that indirectly touch the customer. This ability to allow for task or action level thinking without having to collect all of the data on what these tasks are is one of the strengths of the VCMS. It provides an elegant way to capture the impact of task detail without the laborious process of identifying and tracking each action taken in the firm.

So, what are some of the common activities in a firm that are predominantly BVAI? They would include the following:

• Purchase order processing

• Preparing shipping documents

• Maintaining customer accounts

• Preparing invoices

• All coordination activities, such as scheduling

• Internal customer tracking and analysis

• Order entry

• Order fulfillment, such as picking the ordered items

• Return processing

• Complaint processing

• Order taking

What all of these types of activities have in common is the fact that if they are done poorly, the customer is directly impacted. Clearly these activities do not make up part of the product or service value proposition, but they can impact customer satisfaction with the transactions that they undertake with the firm.

BVAI, then, is tied to the satisfaction metrics that a firm collects. When customers are satisfied with the results of a transaction with the firm, it usually means that the BVAI element of the firm’s activities have gone so smoothly that they are invisible to the customer. Since satisfaction has long-term implications for the continuation of a customer relationship, tying to the customer’s loyalty to the firm, BVAI actions are critical to long-term survival and growth. That being said, they do not warrant direct payment by the customer, who simply expects them to be done quickly and correctly.

If a service logic approach2 is taken to the customer relationship, many of these activities could be classified as part of the responsiveness or quality of service component of the value proposition. This fact underscores why some of the activities in Figure 3.1 have some value-add even when the function of setting operational meetings and requirements itself would probably be dominantly classified as administrative work. There is value-add in all corners of the organization and a surprising number of places where BVAI occurs. Whenever an action is one step removed from directly touching the customer, it is a BVAI action.

BVAF—Building the Future of the Business

One of the most important things for a firm’s long-term survival is its ability to create new products and services and to sell these new products and services to new and existing customers. What is fascinating about business value-add—future (BVAF) activities, then, is that they are forward-looking but actually are not valued by a customer buying today’s products. If you just made a decision to buy a new computer, for instance, you are not happy (nor factor into your price) the fact that a new model is released the next day. BVAF activities can actually make today’s customers feel as though they’ve been cheated out of extra value because they made a purchase decision—they draw the entire purchase decision into question.

A company, though, always needs to be looking to the next transaction, or the next purchase of its goods and services. While today’s sales may be the source of celebration, once the confetti settles it’s time to get back to work to generate new products and new sales. So, even though today’s customers won’t pay for BVAF actions or activities, future customers will. In cutting costs, then, BVAF activities may seem discretionary, but they are actually essential to long-term survival and growth. Companies that fail to plan for the future will find themselves out of touch with the market and in a losing situation.

Once again returning to Easy Air, we see in Figure 3.2 that a marketing department has a heavy component of BVAF in its core activities. For instance, strategic planning is essential for the long-term survival of Easy Air, so it is deemed to be 95% BVAF. Clearly today’s customers don’t really care if a company does any strategic planning at all, but if the company is to be around for tomorrow’s customers it is a vital activity.

Figure 3.2. Business value-add—future.

NOTE: Each of the rows should sum to 100% of the available time and effort the activity consumes.

What are some of the activities that take place in a firm that are predominantly BVAF in nature? They would include the following:

• Strategic planning

• Pricing analysis

• Customer research

• Product development

• Basic research

• Proposal development

• Marketing analysis

• Advertising

• Marketing research

• Design for manufacturability

• Process improvement efforts, such as lean management

• Customer focus groups

• Customer satisfaction studies

This list could be much longer. A well-run organization is always looking forward, so it spends a significant amount of its time and resources making sure it has the next new product or service offering ready to hit the market when the timing is deemed right. In fact, it is common knowledge that firms such as Sony and Apple plan for their own products’ obsolescence and replacement by new models out six or seven iterations. Since it takes time to bring new products into the market, the firm has to be constantly looking forward to ensure that it remains viable in the marketplace.

BVAF, then, is definitely value-adding from the shareholder perspective. Investors in a firm are buying its future cash flows, not its current or past ones. While the VCMS focuses on customers, the management of the firm has to keep the expectations of all of its stakeholders in mind. Today’s customers may generate today’s revenues and profits, but tomorrow’s products and services are the basis for investors to provide vital working capital to the firm.

Finally, unfortunately for many companies, financial accounting often categorizes BVAF actions and activities as discretionary. This approach means that when times get tight, these activities may be curtailed, increasing current profitability. But this increase in current profits comes at a high cost—tomorrow’s survival and possible success. These activities are hardly discretionary for a firm focused on its future growth. The VCMS does a better job of isolating those factors that drive future growth. These BVAF activities are second in line for protection when cost cutting takes place. Removing costs should come from administrative and waste activities first and foremost, with the savings reinvested in current value-add and future value-add activities. While every activity can always be done more effectively, planning for the future is not an option—it is essential to business survival.

BVAA—Administration, or Feeding the Beast

One of the functions most poorly contained in many companies is its administrative work. Reflecting tasks that focus on internal communication and coordination, business value-add—administrative (BVAA) activities do not add value to the company in the short- or long-term. No customer is going to pay a company for holding its meetings or for the reports management requests. While some level of administrative work, such as processing payroll, is important to the individuals in the firm, these activities never create value and can, in fact, become value destroyers.

Much of the work that takes place to coordinate and communicate across the value chain falls into the administrative category. In fact, supply chain partners can be a source of this nonvalue-added category of work. This fact underscores why it is important for the term customer to mean the final consumer—value chain partners may require work that doesn’t in any way impact the final value contained in a product or service. These activities may generate cost and reduce profits—they can never grow the top line. When negotiating with trading partners, then, a company should identify and work to eliminate unnecessary BVAA activities from the relationship.

The more complex or bureaucratic an organization is the larger percentage of its resources may be used for internal coordination activities. It is also an area where waste can become rampant because BVAA activities are hard to measure and control. Who can really say what the importance of a single meeting is? Because it is so hard to define what the right amount of administrative work is from an internal perspective, companies are turning to benchmarking to identify best practice in administrative work.

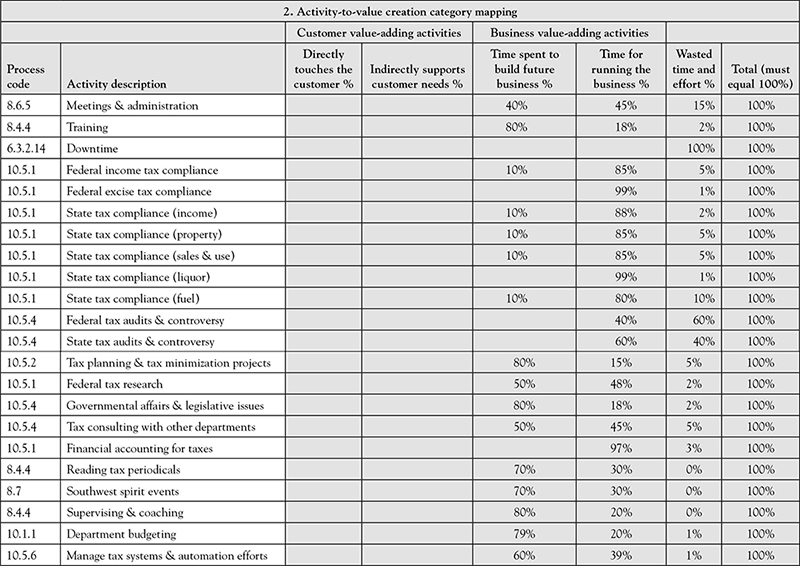

As can be seen in Figure 3.3 taken from Easy Air, areas such as the corporate tax department are predominantly BVAA in nature. The company has to pay its taxes, and can gain profitability from a good tax strategy, but no real value is created for customers with this work. As can be seen, though, there is some future value add in these activities because good tax positioning has a major impact on future profitability.

Figure 3.3. Business value-add—administrative (continued).

NOTE: Each of the rows should sum to 100% of the available time and effort the activity consumes.

In this list of tax-driven activities, research has a significant amount of future value-add while filling out and filing liquor tax forms is deemed to be purely administrative. Compliance activities, while essential if the firm is to stay in business, never create value for today’s or tomorrow’s customers.

The goal in the BVAA arena, then, is to do these tasks as efficiently as possible. When cost cutting is needed, these are the first activities that should be targeted. In fact, many companies today outsource these activities to firms that specialize in them because they have found this is the most efficient way to get the tasks done. Some companies outsource their payroll function, for instance, to firms such as EDS that specialize in payroll activities. Given the complexity in complying to all the regulations and tax laws that surround payroll, this outsourcing might make good business sense.

In other organizations, centralization of these tasks for an entire group of subunits is common. For instance, at Johnson & Johnson, all accounts payable for the corporation’s many companies are processed at one central site. This allows for gains in efficiency through the use of advanced technologies that could not be justified on a subunit level. So, what are the kinds of activities or tasks that fall into administrative categories? They include the following:

• Meetings

• Reports

• Compliance work

• Tax accounting

• Financial accounting

• Accounts payable

• Accounts receivable

• Purchasing

• Payroll

• Scheduling

• Management

What all of these activities have in common is that they exist solely to keep the organization functioning. No customer, whether current or future, benefits from this work. It is even difficult to argue that any stakeholder benefits from these activities. That is why in several companies this type of work was referred to as “feeding the beast.” Management drives this cost area. Management is the only party that can be said to benefit from these activities. The question is how much time and effort should go into management activities?

At one firm that had adopted team-based management approaches, the extreme impact of management methods on BVAA levels in a firm were seen. In this bicycle manufacturing firm, four to six hours of each manager’s day was spent in meetings. When did these individuals get their real work done? It was mostly done in the evenings and on weekends. The managers of the company were still held accountable for accomplishing their primary jobs, but there wasn’t enough time left in the work day to get it done. This extreme case illustrates the fact that BVAA activities can become profit destroyers quite rapidly if not aggressively managed.

Administrative functions seem to grow of their own accord. For instance, in many colleges the number of students that the campus can accommodate is capped by classroom and dorm capacity. The number of faculty, who are direct labor, is tied to the student enrollment. However, even though we observe the same numbers of students graduating and taught by the same number of faculty, we sometimes see more and more layers of administrators added to the organizations, explaining some of the observed increases in tuition.

Administrative work, even when necessary, should be contained. Growth in administrative areas should be closely monitored and examined to make sure there really is a justification for adding more personnel. Otherwise management can be caught up in the trap of spending more and more resources to manage itself. Since these activity costs come directly out of profit and will never generate a penny in revenue, they should be tightly controlled to ensure that the future of the firm is not put at risk. Feeding the beast has to be an activity constantly placed on a “diet” to lessen its impact on current and future profitability.

Summary

This chapter has looked at the various types of business value-added activities that can take place in an organization. Using examples taken from Easy Air, we identified how one specific activity can have portions of value-add, BVAI, BVAF, BVAA, and waste embedded in it. In reality, this information taps the task level of an activity, but it does so without requiring the individual manager to actually lay out the details of how work is done. This innovation in data collection separates the VCMS from most activity-based cost systems that place an activity completely within either value-add or nonvalue-add categories.

For all business value-add activities, making the dollars spent stretch as far as possible is the key. Since they don’t generate any revenue today, the spending can only come from one place—profit. Business value-add activities can squeeze the profit right out of a firm. They reflect management decisions and management actions that do not tie directly to the company’s current value proposition.

That being said, it is important to protect many of the activities that are predominantly business value-add—future. These are activities that ensure the future viability and success of the organization, and hence are actually seen as value-adding by the firm’s shareholders. Far from being discretionary in nature, BVAF activities are the source for long-term growth and sustainability.

There are many ways that companies can contain the costs of administrative work, including outsourcing and centralization of tasks. When lean initiatives are launched, the very first place they should be focused is on BVAA activities because these are not profit generating but rather rob the firm of its profitability. Every activity has some level of administration in it. The goal is to make this as small a portion as is feasible and still retain control of the organization.

By creating this robust categorization of business activities, the VCMS expands the knowledge created by activity analysis and process improvement programs. It also more accurately reflects the reality on the ground—what individuals really see as the costs and benefits of their activities. Having looked at this area in depth, then, let’s turn our attention to waste, the profit bandit.

The important thing is this: to be able at any moment to sacrifice what we are for what we could become.

Charles Du Bos3