It is good to have an end to journey toward; but it is the journey that matters, in the end.

Ursula K. Le Guin1

The journey through the different aspects of the value-based cost management system (VCMS) is now complete. We’ve seen examples of many companies that have used the model in a variety of ways to address strategic, tactical, and operational problems. Some companies have built an entirely new control approach using the logic of customer value as the driving force. We’ve also seen how the VCMS fits seamlessly with many of the advanced management techniques, such as process management, value engineering, and target costing. It is a tool that starts from a set of simple assumptions and results in a rich body of knowledge about what a company does right—and wrong.

In this chapter we’re going to summarize the basics of what has been presented in the previous pages. We will provide an overview of the model and how it has been used in participating organizations. The goal is to capture the knowledge and learning resulting from the VCMS. Let’s start by reviewing the basics once more.

The VCMS Model—The Basics Revisited

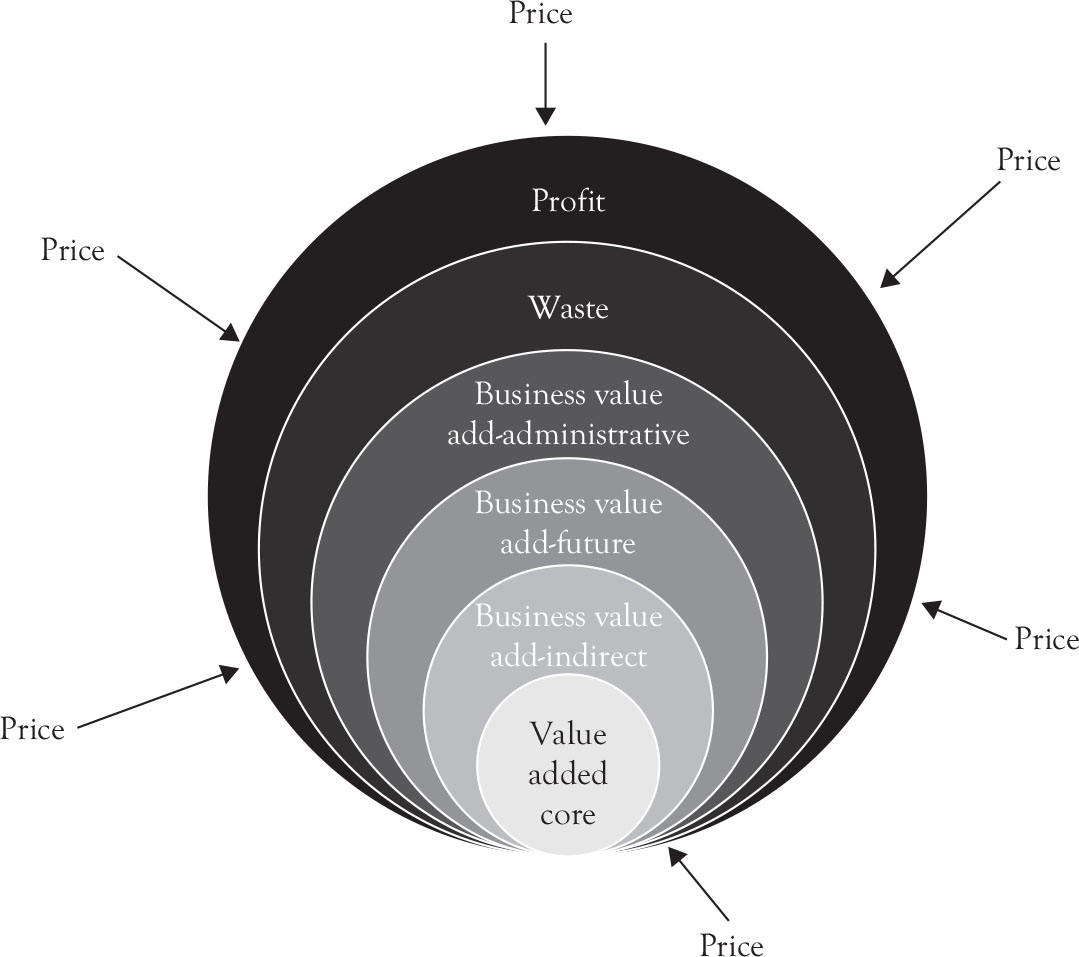

The heart of the VCMS is its view of customer value in the marketplace and the internal cost structure of the firm. A second key element is the application of value attributes to the revenue stream to generate revenue equivalents. These two basic additions to the existing activity analysis literature result in a rich model that supports a wide range of decisions and actions. What did the basic cost breakdown of a firm look like from a market perspective? Figure 12.1 reintroduces the basic model.

Figure 12.1. Cost from a market perspective.

The model begins by taking the market price as the disciplining factor in any company. Unless a firm operates in a pure monopoly, it doesn’t control its final price. Most firms have some power over price but this power depends on the degree of competition in their markets. Successful companies have to master how to make a profit within the competitive constraints of their markets. The competitive marketplace is constantly putting pressure on this price window, as company after company seeks to gain business by offering the same or slightly different products and services for less money. Price, then, sets an outside limit on how much a profit-making organization can afford to spend to deliver a specific product or service.

The spending that generates the price of a product is called the value-added core of activities. In our field work we found value-added core to represent about 20–25% of the total spending in a company. The value-added core is to be protected at all costs. This is one of the key lessons learned—spending cuts should never target those activities qualified as customer value-add. To cut the value-added core results in a collapse of the value profile of the firm, reducing the price a customer might be willing to pay for the affected product or service. The value-added core is supported by many individuals in the organization, either directly or indirectly. No one activity is purely value-add or nonvalue-add because activities consist of tasks, some more valuable to the customer than others.

The value-added core consists of a set of value attributes that combine to make the value profile of a product or service. The VCMS uses this value profile to develop revenue equivalents, or estimates of how much of the revenue earned is based on specific value attributes. The information for the weighting of the value attributes in the value profile is developed using customer data. In our work we often found that management did not truly understand the value profile of its customers and how much different value attributes are worth in the overall profile.

Combining the revenue equivalents with the value-added costs provides a series of value multipliers. These multipliers are strategic signals about how effectively the firm is using its resources and thereby spending its money. If a value multiplier is low (below four), it means the firm is spending too much to deliver on that value attribute. If the multiplier is high (greater than seven), it can either be a competitive advantage—the firm is really good at delivering this component of value—or the company is under-spending on the attribute, resulting in dissatisfied customers. In this manner the VCMS provides detailed signals to management about how effectively they are using the organization’s funds to create the right type of value for their customers.

Beyond Value-Add

The first ring out from value-add in Figure 12.1 is the Business Value-Add—indirect (BVAI). This consists of all of the aspects of an activity that could result in an unhappy customer if not done well. Some companies, such as Easy Air, have decided that these activities are so important to the overall experience a customer has with a company that they should be included in the value-based analysis of the firm. Most other companies have left them out of value-add because they really do not generate price, they only affect satisfaction. Since a satisfied customer is more likely to become a loyal customer, though, there is ample evidence to say that these activities and their underlying tasks need to be carefully studied to ensure they are done well. Cost cutting in this category should be done with care, with a constant eye toward the ultimate impact on the customer’s experience with the organization.

Next we see Business Value-Add—future (BVAF). The activities in this ring are all of the things a company does to ensure that it has something to offer to future customers. Consisting of things such as research and development and marketing efforts, these activities are critical from the perspective of the firm’s owners. Only firms that continue to innovate can truly compete in the long run in the marketplace. The dollars spent in this category are an investment of funds from today’s sales that helps ensure that the organization remains viable in the future. These are not discretionary expenditures, as financial accounting tags them, but vital for the health of the organization. Cost cutting should not take place here unless there are no other options left to the firm.

The third ring out from the value-added core is Business Value-Add—administrative (BVAA). Here we see all of the activities and tasks that are undertaken solely to support the functioning of the organization—they don’t result in any revenue today or tomorrow. A customer doesn’t care how a company manages itself. Since there is no value-add in these activities, they should be carefully monitored to ensure they don’t grow beyond a reasonable level. In our work we found this level to be at about 10–15% of the total revenues earned. As companies mature, we often notice that BVAA activities begin to consume more and more of the scarce dollars earned by the value-added core of the product and service attributes. When cost cutting needs to take place, this is one of the first places the firm should review. It is no accident that the majority of the lean management exercises emphasize administrative tasks—they simply add no value to the customer.

Waste is the fourth ring out. There is no benefit to either the organization or the customer from waste. Whether it comes from rework, excess processing, or even excess value in a product, it is to be eliminated wherever it occurs. One of the simplest examples of how a company can actually create waste with something that probably was considered by management to be part of the value-added core is Tupperware®. This is a product that is built to last, but unfortunately the original owner seldom gets to use up the value in the product—the pieces end up in someone else’s kitchen (most likely one’s children), being used but not by the person who paid the premium price for the product. This excess value led to the creation of more disposable, and much less expensive, market alternatives to the Tupperware® brand. The excess value ends up being waste to the consumer who purchased the product. Clearly this isn’t the case for all of the products made by this company, but it does apply to many of their offerings.

Finally, given the market conditions, and if resources were consumed with care by the activities of the firm, the company might generate positive profit. There is always a squeeze on profit, though, as market forces continue to put pressure on price, one of the boundaries of profit, and internal costs tend to creep over time, putting pressure on profit’s other boundary. Protecting the company profit starts by understanding how resources are consumed and using disciplined approaches to minimize internal cost increases.

The VCMS model, then, allows a firm to separate out the various types of costs at the activity level, implicitly tying the costing process to the tasks that make up an activity. While an activity may be 30% value-add, there is undoubtedly some BVAA required to meet internal communication needs. And, some level of waste exists in most activities that are performed in a company. Getting rid of this waste has spawned an entire discipline—lean management. The VCMS supports lean management by identifying those activities where waste is hidden, helping to prioritize improvement efforts.

Strategic, Tactical, and Operational Uses of the VCMS

The value multipliers developed as part of a VCMS study are one of the ways in which the model provides strategic information to a firm. As we saw at both GTI and Impact Communications, this information can serve as a surprise—management learns they are not putting the firm’s resources into the right activities. We also learned that customers can often be segmented by offering different products that have different value profiles. This can be a challenge for a firm that is used to providing the same product to all its customers. Different customer segments require different types of effort from the firm.

As we saw at Windows, Inc. their grouping of value profiles led to the definition of separate segments consisting of architects and small builders. These segments have important power in the value chain but they are not the final customers of the product. They may influence the buying decision, and they most likely insert additional demands on the company’s resources in the buying process. Managing these business-to-business activities has to be done with an eye on the additional costs and benefits incurred, given that they are most often BVAA activities in the customer’s eyes. Since these activities can reduce profit, they have to be performed as efficiently as possible. In our field work with Windows, Inc. we found that these trading partners were important for them and that it was in their best interest to understand their needs and see how best to meet them in order to protect profitability and value delivered to final customers. That being said, these costs still had to be managed with an eye toward protecting profitability.

The VCMS was originally designed as a strategic tool, but once it was implemented in companies it began to be apparent that the depth of the activity analysis additionally supported both tactical and operational decision-making. At the tactical level, the VCMS supports three key modern management models—value engineering, target costing, and lean management. For target costing and value engineering, the customer data can be immediately matched up with the internal activities required to deliver specific customer value. This is most valuable in the support dimension, where the traditional flat overhead rate is replaced by activity-specific costs. At Windows, Inc. a series of product development decisions was supported by the VCMS model. This included the tactical decision about many different sizes and colors of windows and doors were needed to gain a foothold in the marketplace with their new product line.

Easy Air used the VCMS data in a tactical way to study their routing structure and change these structures as a result of information provided by the VCMS. For instance, the VCMS data helped support incremental analysis of the differences between short-haul and long-haul flights. The result was to create a separate customer segment for the long-haul planes. By changing the way the management thought about long-haul flights, decoupling them from regional systems, the firm was able to improve its on-time performance rating, one of the critical statistics measuring airline quality. Since long-haul planes dragged variation with them from one coast to another, this decoupling allowed the company to neutralize this excess variation and return to better performance overall.

Impact Communications also made a combination of strategic, tactical, and operational changes to their operations based on the VCMS-based learning. Discovering that they were only serving one segment of their customer population well, two major changes were made. Structurally, resources were shifted from the research activity to the publicity activities in the firm. This was a major cultural change, as the firm had grown up around the research skills of its founder.

A second operational change was then made at Impact Communications. Engagement discussions with customers were altered to include a discussion of how the customer wanted the firm to spend their engagement dollars—what value attributes were most important to the customer. This new information was used to guide the development of the engagement plan and to report back to customers as the job progressed. These changes helped to create a new focus for the company’s employees, one that was more aligned with their strategic markets and their needs.

Tying VCMS to Other Initiatives

As has been noted throughout this discussion, the VCMS is a natural partner to several other modern management techniques used in organizations today. First and foremost, it supports process management. The process codes for activities can be built directly into the data collection effort. Using a framework, such as the APQC model, we have seen how the process information can be developed.

At the USCGA, process coding allowed the organization to understand how much value it was delivering and where. The organization had never taken a process view of its operations before, so the new insights were quite valuable. While most of the resources were directed toward cadets in today’s program, significant resources were directed toward the processes needed to identify and obtain new cadets that met the rigorous acceptance criteria for the USCGA. The organization also spent significant funds maintaining its physical and financial resources—these were the highest processes in terms of total cost and time. Tied to the structure of the organization, it was difficult for the USCGA to change its process spending, but putting new light on this spending led to discussions to renegotiate some of the contracts used for outsourcing some of the maintenance work on campus.

Easy Air also performed extensive process coding during the collection phase. Since the firm was so committed to customer service, they were pleasantly surprised when the combination of direct and indirect value-add was so high for the processes that mattered to customers. This didn’t lead to change, as the firm was satisfied that it was directing it operational funds in the right places. It reinforced that management had a good handle on how best to serve the customer.

We have also noted that the VCMS supports target costing. At Windows, Inc. the cost breakdown for the new window was estimated using proxies from the data collection phase of the VCMS. Using the existing structure of the organization, costs were assigned across the five categories of value-add itself, BVAI, BVAF, BVAA, and waste. This knowledge triggered an intense focus on disciplining the spending on nonvalue-adding activities, leading to a change in how supplier relationships were handled, including the use of the firm’s own vacuum forming operation. Unnecessary paperwork was eliminated as a streamlined back office set of routines was developed. The new window was not launched immediately because it couldn’t meet its target cost, but additional value engineering finally led to the successful release of the new product line several years later.

The VCMS supports value engineering by matching up the value attributes with the current costs to deliver on those attributes. What is added to value engineering is the further breakdown of the support costs into specific activities, which can then become the target for reduction as was seen at Windows, Inc. At Frangor, the information from the study led the value engineering team to decide to move to platforms, or families, of products rather than the one-up approach that had been used in the past. This helped reduce raw materials inventories significantly, helping the company to improve its profit picture.

Lean management and the VCMS are natural partners in any organization. Since the VCMS identifies the waste and BVAA levels in the various activities, it supports the prioritization of lean management projects. Since lean management targets the elimination of waste through continuous improvement and process redesign, the information provided by the VCMS can support these efforts, providing information both before and after the process redesign on whether costs have been trimmed. The VCMS was indirectly used by the U.S. Coast Guard Financial Center when it implemented lean management. The categorization of costs by the redesign team allowed the team to focus the new process design to augment the value-adding activities and reduce or eliminate much of the paperwork that had been clogging the system. The result was that the organization was able to take many more of the available prompt payment discounts, saving a significant amount of money in the first few months following the redesign effort. This was money that could be redirected to putting fuel in ships so that they could do more missions—a value-add improvement for the nation.

The VCMS is a natural part of strategic cost analysis, as was once again seen at Frangor. While Frangor gained insights from using the traditional strategic cost categorization of structural and executional cost drivers, it wasn’t until the VCMS study was done that truly actionable information was gained. The VCMS is an extension of strategic cost analysis, one that puts customer-defined value attributes in the driver’s seat for making strategic changes. If savings are reinvested in the value-adding core, the result is a model of growth that helps an organization to accomplish its profitability goals.

Implementation of the VCMS

The implementation of the VCMS starts with customer value data and a clear understanding of the importance of the different value attributes used in customer decisions. Data collection is often done in marketing research departments or data can be purchased from outside vendors. Customer value data is then transformed to the 100 point system necessary for the VCMS using a variety of methods. It is important for the VCMS and its implementation to use current customer data and for the data to reflect a solid understanding of critical attributes and their importance for customer decision-making in relevant markets. When time is of the essence and resources are limited, customer focus groups can be used to obtain customer value information. At Easy Air, surveys were sent to the firm’s frequent flyers to gather this information. Regardless of the method used to collect customer data and value attribute information, it is the starting point for the implementation of the VCMS.

Once the value attributes have been identified, attention turns to gathering internal activity analysis data, which is augmented by process coding in some instances. If process coding isn’t used, then the data collection effort focuses down on classifying the costs spent on an activity to one of the five subcategories of cost. Value-add costs are then assigned to specific value attributes. This data collection effort is supported by software such as an integrated Excel spreadsheet that both tallies the key data points for the respondent and, with the simple addition of a budget figure, results in cost by attribute and category. These data can be combined into either one master data file or a relational database. The relational approach offers more flexibility in the analysis phase and is recommended.

Once all of the data has been collected, a number of reports can be generated, such as a report on where primary value-add is taking place. The data also supports the development of value multipliers, which detail how well the firm is meeting customer value preferences. Very low multipliers mean the firm is overspending on delivering a value attribute. This is the case if the multiplier is below 4. Five is a target number as most firms have been found to have roughly 20% value-added costs in their structure. High multipliers are more difficult to interpret. If the customer is very satisfied with the firm’s performance on an attribute with a high multiplier, then the firm has a competitive advantage. If customers are dissatisfied, however, the firm has a strategic weakness that must be addressed by focusing more resources on the underserved attribute.

During implementation, decisions have to be made as to whether the VCMS study is a one-time event or a new part of the ongoing reporting package of the firm. In most of the companies studied, it was a one-time event. The exception was Impact Communication, where the data was used to create a new management control system that ensured that client engagement dollars were spent according to customer preferences. Building the VCMS into the ongoing reporting package optimizes the impact of this new information and perspective on the adopting organization. If properly administered, it becomes relatively inexpensive to maintain the data on a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis. This is the recommended approach.

Finally, there is always a question about whether a new tool should be coupled with the firm’s management control system. This is not always a good idea as it can lead to false reporting as managers might seek to prove they are value-adding in their activities. Since the data collection process is dependent on accurate reporting by managers, it is important to remember that management control uses of data is a double-edged sword. More control is clearly gained, as attention is shifted to the value attributes, as seen at Impact Communications. But, managers might be less likely to report accurately if they are given targeted levels of value-add. The only way changes can occur in the value component of work is if it is redesigned to optimize the value-adding components. Simply putting a goal out there without providing the tools to reach those goals is counterproductive. Building the VCMS into the firm’s control system, then, should be done with great care. Making value add visible is one thing, holding managers accountable for value-add components when they can’t really control those components can lead to suboptimal behavior and incentive conflicts.

Summary

The VCMS provides a new language for the firm, one that unites everyone around customer value and market perspective of the firm. At Windows, Inc. one of the major benefits gained from its VCMS implementation was that marketing and finance could now communicate more clearly about key goals and results in the firm. The VCMS, then, is a way to bridge the gap between different functional areas in the organization, tying everyone to the customer.

The VCMS model works very well in service organizations. In manufacturing organizations, a further implementation of capacity cost management is useful. This is valuable information for the firm, and has been found to be sustained by the firms as an ongoing reporting package. The breakdown of capacity information into value-add and nonvalue-add components is relatively straightforward.2 This technique was used in many of the firms studied during the VCMS project—it is a critical tool for proper implementation in any setting where machine-paced work exists.

In the end, a company implementing VCMS can decide to use the information for a broad range of strategic, tactical, and operational decisions. Because the VCMS integrates with many of today’s advanced management techniques, it can serve multiple uses in multiple settings. Creating a new language, one that focuses everyone’s eyes on the customer and customer value, it helps create the customer-centered organization. When finance embraces the customer in its reporting packages, the entire organization wins. It is a journey with many benefits, one that begins with understanding customer preferences and ends with making sure they are used to drive internal operations and decision-making.

To be what we are, and to become what we are capable of becoming is the only end of life.

Spinoza3