CODA

Leonardo’s Legacy

I argued in the Prologue to this book that Leonardo’s greatest legacy to us may be his systemic thinking, together with his deep respect for nature and for life. In his mind, the two were closely connected. To gain knowledge about a natural phenomenon, for him, meant connecting it with other phenomena through a similarity of patterns; and such systemic knowledge he also saw as the basis for love. “For in truth,” he asserted, “great love is born of great knowledge of the thing that is loved.”1

Today, it is becoming increasingly evident that systemic thinking is critical to solve our major global problems; yet our sciences and technologies remain narrow in their focus, unable to understand systemic problems from an interdisciplinary perspective; and our business and political leaders are often incapable of “connecting the dots.” This is exactly what we can learn to do from Leonardo da Vinci’s unique synthesis of art, science, and design.

As we recognize that most of our sciences, technologies, and business activities are not life-enhancing but life-destroying, we urgently need a science that honors and respects the unity of all life, recognizes the fundamental interdependence of all natural phenomena, and reconnects us with the living Earth. Indeed, what we need today is the kind of science Leonardo da Vinci anticipated and outlined five hundred years ago.

Leonardo did not pursue science and engineering to dominate nature, as Francis Bacon would advocate a century later. Throughout this book I have shown that he had a deep respect for life, a special compassion for animals, and great awe and reverence for nature’s complexity and abundance. As he put it succinctly: “One who does not respect life does not deserve it.”2

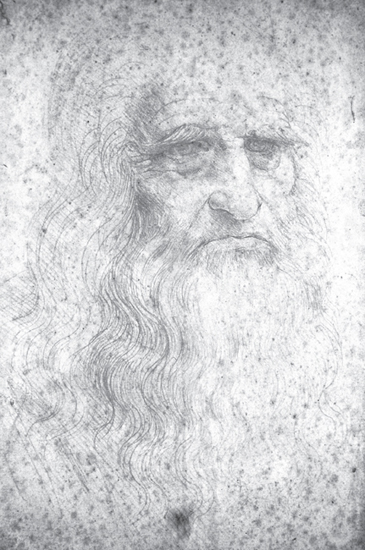

FACING Leonardo’s self-portrait (detail), c. 1512. Biblioteca Reale, Turin.

While a brilliant inventor and designer himself, Leonardo always thought that nature’s ingenuity was vastly superior to human design. He felt that we would be wise to respect nature and learn from her. “Though human ingenuity in various inventions uses different instruments for the same end,” he declared, “it will never discover an invention more beautiful, easier, or more economical than nature’s, because in her inventions nothing is wanting and nothing is superfluous.”3

In the designs of his flying machines, Leonardo tried to imitate the flight of birds so closely that he almost gives the impression of wanting to become a bird.4 He called his flying machine uccello (“bird”), and his designs of its mechanical wings sometimes mimicked the anatomical structure of a bird’s wing so accurately and, one almost feels, lovingly, that it is hard to tell the difference.

This attitude of seeing nature as a model and mentor is now being rediscovered in the practice of ecological design. Like Leonardo da Vinci five hundred years ago, ecodesigners today study the patterns and flows in the natural world and try to incorporate the underlying principles into their design processes.5 When Leonardo designed villas and palaces, he paid special attention to the movements of people and goods through the buildings, applying the metaphor of metabolic processes to his architectural designs.6 He applied the same principles to the design of cities, viewing a city as a kind of organism in which people, material goods, food, water, and waste need to flow with ease for the city to be healthy.

In his extensive projects of hydraulic engineering, Leonardo carefully studied the flow of rivers in order to gently modify their courses by inserting relatively small dams in the right places and at the optimal angles. “A river, to be diverted from one place to another, should be coaxed and not coerced with violence,” he explained.7 These examples of using natural processes as models for human design, and of working with nature rather than trying to dominate her, show clearly that, as a designer, Leonardo worked in the spirit that the ecodesign movement is advocating today.

Leonardo’s deep respect for nature and for life, which is evident in his art, his science, and in his designs, is perhaps his most important legacy for our time. Our great challenge, as I have said, is to build and nurture sustainable communities—communities designed in such a way that their ways of life, businesses, economy, physical structures, and technologies respect, honor, and cooperate with nature’s inherent ability to sustain life. The first step in this endeavor is to become ecologically literate; the second step is to apply our ecological knowledge to the redesign of our technologies and social institutions, so as to bridge the current gap between human design and the ecologically sustainable systems of nature. In both of these endeavors—ecoliteracy and ecodesign—we can find great inspiration in the genius of Leonardo da Vinci.