6

The Body in Motion

Leonardo perceived the living world as being in constant flux, its forms merely stages in continual processes of transformation; so it was natural for him to also understand the human body in terms of movement and development. He saw the body’s continuous movements—epitomized in flowing gestures, curling hair, or floating draperies—as visible expressions of grace, and he was a master in portraying such graceful movements in his paintings. The Madonna and Child with Saint Anne (plate 7) is perhaps his finest demonstration of graceful gestures fused into a single, continuous flow.

The association of grace with smooth, flowing movements was common among artists in the Renaissance, but Leonardo was the only one who attempted to understand it within a scientific framework.1 His analytic mind was fascinated by the autonomous, voluntary movements of the human body. Their investigation became a major theme in his anatomical work. In countless dissections and detailed anatomical drawings he explored the transmission of the forces underlying various bodily movements, from their origins in the center of the brain down the spinal cord, and through the peripheral motor nerves to the muscles, tendons, and bones.

Leonardo realized that in this propagation of the motor forces, their exact origins in the brain and transmissions through nerve impulses were invisible and hence inaccessible to further scientific analysis. He hypothesized that these pulses traveled through the nerves in the form of waves, and he called their movement “spiritual,” by which he simply meant that it was immaterial and invisible.2 Here is how he described the functional links between nerve impulses, muscles, tendons, and bones:

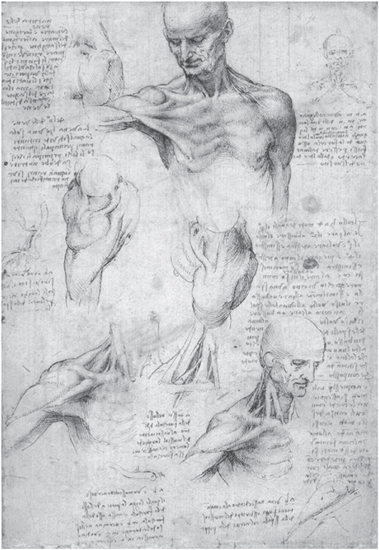

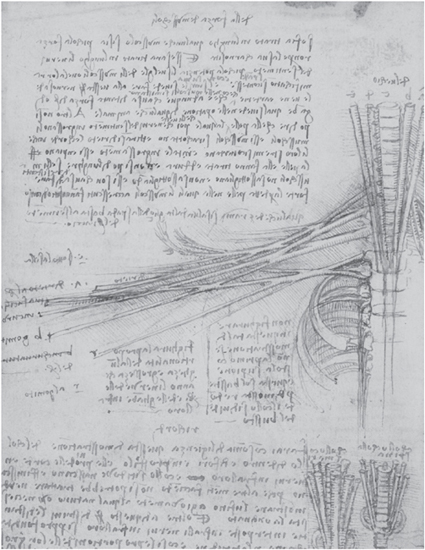

FACING Rotated views of the muscles of the shoulder and arm, c. 1509–10 (detail, see plate 4).

Spiritual movement, flowing through the limbs of sentient animals, broadens their muscles. Thus broadened, these muscles become shortened and draw back the tendons that are connected to them. This is the origin of force in the human limbs…. Material movement arises from the immaterial.3

At various stages in his anatomical research, Leonardo investigated all the sections of this pathway of the body’s motor forces. He began with detailed explorations of the brain, the cranial nerves, and the spinal cord,4 and then proceeded, during the years 1506–8, with a series of anatomical drawings that are composite representations of several systems—nerves and muscles, muscles and bones, bones and blood vessels, and so forth—as well as representations of the entire body.5

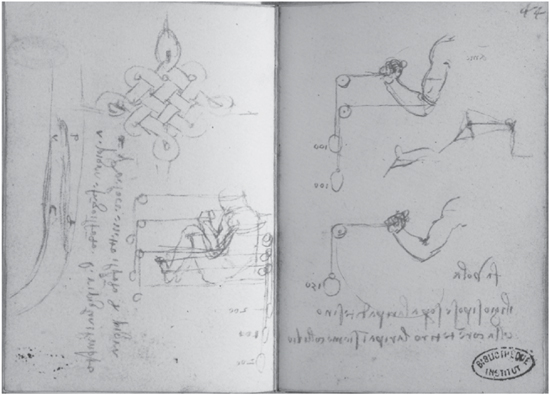

FIG. 6-1. Measurements of muscular forces. Ms. H, folio 43v (left) and folio 44r (right).

By that time, Leonardo had acquired sufficient understanding of the principles of mechanics to explore in detail how nature’s “mechanical instruments”—the muscles, tendons, and bones—work together to move the body. In numerous drawings, he showed how joints operate like hinges, tendons like cords, and bones like levers; for example, in his exquisite demonstrations of the complex movements of the foot (see fig. 4-7), the arm (plate 3), and the hand (see fig. 4-2). He applied his knowledge of the rotational motion of axles to the movement of the “universal” ball-and-socket joints of the hip and shoulder.6 In some anatomical studies, Leonardo drew cords or wires instead of muscles to better demonstrate the directions of their forces (see figs. 4-2 and 6-9). He also measured muscular forces by fastening cords to the hands and feet of a person and running them over pulleys with weights attached at their ends, not unlike modern weight-lifting machines (fig. 6-1).

Varieties of Bodily Movements

Leonardo used his knowledge of the mechanics of bodily movement to analyze a wide variety of actions of the human body down to their finest details. “After the demonstration of all the parts of the limbs of man and of the other animals,” he wrote in a note to himself, “you will represent the proper operations of these limbs, that is in rising from lying down; in walking, running, and jumping in various ways; in lifting and carrying heavy weights; in throwing things to a distance, and in swimming; and thus in every action you will demonstrate which limbs and muscles cause the aforementioned operations.”7 Like the research projects in other branches of his science, Leonardo’s program of anatomical research regarding bodily movements was comprehensive and very ambitious. It is also noteworthy that in this passage, as in many others, he considered the human body an animal body, as we do in biology today.

Leonardo distinguished between three types of bodily movements. “The movements of animals are of two kinds,” he explained, “that is, motion in space (moto locale) and motion of action (moto azionale). Motion in space is when the animal moves from place to place; and motion of action is the movement which the animal makes within itself without change of place; … and the third is the composite movement (moto composto), combining action with locomotion.”8

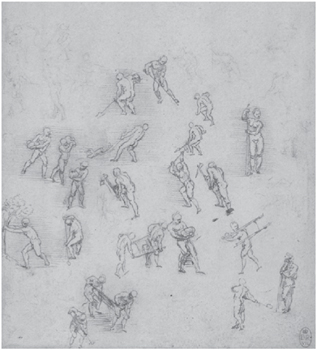

Movements of action, for Leonardo, included not only external bodily movements, such as pushing, pulling, and lifting, but also movements in the body’s internal physiology, like breathing and digesting food. In the Windsor Collection, there are several folios with sketches of small naked figures performing a variety of actions (fig. 6-2), and the Notebooks also contain numerous detailed written descriptions of the combined operations of specific muscles and joints in carrying out those bodily movements.9 In addition, Leonardo undertook elaborate studies of the actions of the heart, the lungs, and other internal organs (see chapter 8).

FIG. 6-2. Study of figures in action, c. 1506–8. Windsor Collection, Figure Studies, Profiles, and Caricatures, RL 12644r (detail).

In his analysis of movements in space, or locomotion, Leonardo paid special attention to the positions of the body’s center of gravity during the various phases of a particular movement. He observed that “motion is created by the destruction of equilibrium, that is, of equality [of weight]”;10 and furthermore, that “the locomotion of man or any other animal will be of as greater or less velocity as their center of gravity is further away from, or nearer to, the center of the supporting foot.”11 The Notebooks contain meticulous descriptions of successive shifts of positions in rising up from the ground, walking uphill (or against the wind) and downhill, running, and jumping.12

In particular, Leonardo was keenly aware of the undulating movements of the spine and body during walking and running. He noted the corresponding rise and fall of the shoulders and recognized accurately that these wave movements are possible because the spine is composed of many small bones (the vertebrae) strung together in a flexible column. On a sheet in the Windsor Collection (fig. 6-3), Leonardo’s understanding of the undulating movements of the spine is vividly illustrated in a series of sketches of horses, cats, and—charmingly—dragons. The accompanying text explains that the “serpentine winding” of the spine in the movements of these animals takes place longitudinally as well as laterally. During the same period, Leonardo produced a magnificent study of the vertebrae and vertebral column (see fig. 6-8), one of his most famous anatomical drawings.

FIG. 6-3. Studies of flexions of the spine in the movements of horses, cats, and dragons, c. 1508. Windsor Collection, Horses and Other Animals, folio 158.

In his instructions to painters on how to render human figures, Leonardo emphasized repeatedly that the figures’ gestures and movements should portray the frame of mind—the thoughts, intentions, and emotions—that provoked them. “The most important thing that can be found in the discourses on painting,” he wrote, “are the movements appropriate to the states of mind of each living creature, such as desire, contempt, anger, pity, and the like.”13 He admonished painters to “give your figures an attitude that is adequate to show what the figure has in mind.”14

Leonardo saw the movements of the human body as the visible expressions of mental movements (moti mentali). Indeed, to portray the body’s expressions of the human spirit was, in his view, the artist’s highest aspiration. “That figure is not worthy of praise,” he declared, “if it does not, as much as possible, express in gestures the passion of its spirit.”15 Leonardo himself excelled at this task. His celebrated Last Supper became famous throughout Europe immediately after its completion because of its novel composition and because of the eloquence and power of the protagonists’ gestures and facial expressions, which displayed a wide range of intense emotions.16 Similarly, the paintings of Leonardo’s mature period, including the Saint Anne and the Mona Lisa, have always been considered masterpieces for the expression of their figures’ inner lives.

Anatomy in the Renaissance

When we look at the large collection of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings,* we marvel at their great accuracy and artistic beauty, but it is not easy to realize just how revolutionary they were in their time. Today we are used to seeing detailed wall charts of bones, muscles, and nerves in hospitals and doctors’ offices, and we tend to forget that no even moderately accurate visualization of internal anatomical features was available to Leonardo’s contemporaries. Even in the leading anatomical textbooks of the time, the body’s internal organs and tissues were shown merely in diagrammatic or symbolic forms. Leonardo, by contrast, represented the various parts of the body realistically, with their accurate shapes and relative positions, shown from several perspectives, and within the context of the body as a whole. “My configuration of the human body,” he declared proudly, “will be demonstrated to you just as if you had the natural man before you.”17

To fully appreciate the genius of Leonardo the anatomist, then, we need to juxtapose his drawings with the schematic illustrations that were typically found in the scholastic anatomical texts between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. This has been done only recently. It is one of the novel features of a systematic revaluation of Leonardo’s anatomical work by science historian Domenico Laurenza.18 In his book Leonardo: L’anatomia, published in 2009, Laurenza carefully reconstructs how Leonardo moved among the leading physicians and anatomists of his time, how he studied the classical texts, was influenced by their anatomical visualizations, and then revolutionized them.

The integration of art and science—one of the defining characteristics of Leonardo’s entire oeuvre—is apparent already in his earliest anatomical studies. According to Laurenza, the young Leonardo encountered two distinct anatomical schools that had been brought forth by the Italian Renaissance—the “anatomy of the artists” and the “anatomy of the doctors.” The former was centered in Florence, the latter in Milan and Pavia. Leonardo maintained contacts with both schools, was influenced by both, and integrated their different approaches in his science and his art.

Many Florentine artists in the Renaissance had a keen interest in the anatomical study of muscles, which sometimes included dissections, so as to portray the gestures and movements of the human body—especially those of heroic, muscular figures—in realistic and expressive ways. Whereas Michelangelo was the outstanding artist of that school, a very influential early representative was the painter and sculptor Antonio del Pollaiolo, whose studies and paintings of muscular nudes were widely copied and became important models for other artists.19 Pollaiolo’s workshop was not far from the bottega of Andrea del Verrocchio where Leonardo received his training,20 and it is possible that the young Leonardo observed dissections being carried out by Pollaiolo.21

Studies of the superficial anatomy of muscles were also an integral part of Leonardo’s apprenticeship. In Verrocchio’s bottega, plaster models of human limbs were made for that purpose, along with direct observation of the body’s musculature. Leonardo demonstrated his considerable knowledge of the surface anatomy of muscles in one of his first paintings, the Saint Jerome (1480), in which the ascetic saint’s pain and sorrow are powerfully expressed in the tense musculature of his neck and shoulder.22

The “anatomy of the artists” was largely limited to these superficial studies of muscles for portrayals of bodily gestures and movements. The necessity of anatomical studies for artists had already been emphasized by Leon Battista Alberti, a “universal man” and great idol of the young Leonardo.23 In his book De pictura (On Painting), published in 1435, Alberti explained that bodily movement was the result of the concerted actions of nerves, muscles, tendons, and bones, and he encouraged artists to study all of these anatomical parts. However, before Leonardo none of the Florentine artists followed Alberti’s exhortation, limiting their studies largely to external examinations of muscular or emaciated bodies.

Leonardo’s contacts with the “anatomy of the doctors” also began during his youth in Florence. At the age of twenty, he had completed his apprenticeship, was recognized as a master painter, and was admitted to the guild of painters known as Compagnia di San Luca. Curiously, this guild also included physicians and apothecaries and was based in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova. For Leonardo, this was the beginning of a long association with the hospital. For many years he used the guild as a bank for his savings, and his frequent visits to Santa Maria Nuova provided ample opportunities for him to mingle with some of Florence’s leading physicians and anatomists.

It was customary at the time to perform autopsies in order to ascertain the cause of death in many cases.24 The city of Florence was a leader in these practices, which were also occasions for new anatomical knowledge, and many of these post-mortems were carried out at Santa Maria Nuova. Leonardo very likely observed some of them at the hospital, and we know that he practiced dissections there himself when he was in his mid-fifties.

Leonardo’s engagement with the anatomy of the doctors intensified after his move to Milan in 1482 at the age of thirty. At the Sforza court, he encountered a culture that was much more intellectual than artistic.25 It was linked to the great universities of northern Italy, especially to the University of Pavia, which housed one of the leading medical schools of the time.

Leonardo adapted brilliantly to Milan’s intellectual culture. Soon after his arrival, he embarked on an intense program of self-education involving systematic studies of the major fields of knowledge of his time. Contacts with scholars at the University of Pavia played an important role in this endeavor. Several medical scholars and anatomists lent him medical texts, provided him with explanations, and taught him how to dissect.

In Milan, Leonardo’s anatomical studies went far beyond the superficial anatomies of the artists, but eventually he would integrate both approaches, verifying by means of dissection what he observed externally. The result was a series of “mixed” anatomical drawings (fig. 6-4), which he called images “between anatomy and the living.”26

The Classical Medical Texts

During the Italian Renaissance, medical teaching at the great universities was based on the classical texts of Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna.27 Most professors interpreted the classics without questioning them or comparing them with clinical experience. Practicing physicians, on the other hand, many of them without medical degrees, used their own eclectic combinations of therapies, including bloodletting and surgeries, which were often arranged according to the astrological calendar.

Leonardo carefully studied the classical medical texts, but he differed dramatically from most other Renaissance scholars by refusing to blindly accept the pronouncements of the classical authorities. In his anatomical studies, he generally began with summaries of their teachings, often transforming confusing written descriptions into far more intelligible visual forms. He would then proceed to verify the classical texts with his own dissections and, in doing so, did not hesitate to depart from the authorities by correcting them and adding new anatomical structures he had discovered.

The medical texts studied by Leonardo included the three classics that were most popular and most easily available during his time: De usu partium (On the Usefulness of the Parts) by Galen, the Canon of Medicine by Avicenna, and the Anatomia by Mondino (see pp. 144–45). He also owned a copy of the Fasciculus medicinae (Medical Collection), the first illustrated collection of medical texts, which included Mondino’s Anatomia in its Italian edition. In addition, Leonardo borrowed other texts on medicine and anatomy from scholars known to him. All in all, he mentions about a dozen such works in his Notebooks.28

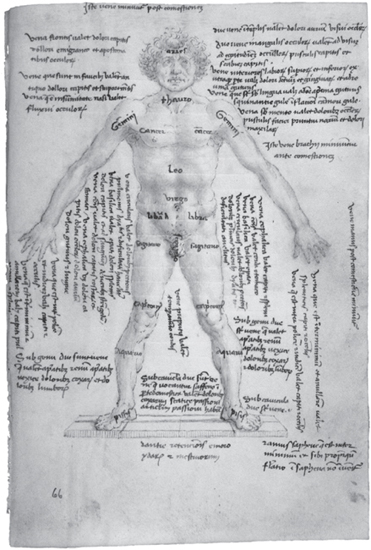

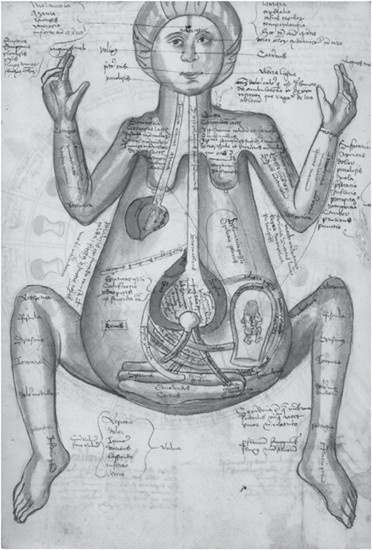

Before the publication of the Fasciculus medicinae in 1491, medical texts were not illustrated, but in some of them a separate plate was inserted at the end of the treatise, sometimes by a subsequent reader of the text. Some of these plates of medical or anatomical illustrations were also available as loose leaflets, independent of the original treatise. Laurenza reproduces and discusses several of these early medical illustrations in his book. One of them, created by an anonymous Florentine artist in the 1470s and inserted at the end of a handwritten copy of Mondino’s Anatomia, shows a human figure surrounded by lines of text (fig. 6-5). This plate exhibits several features that are typical of the medical illustrations of the time.

FIG. 6-4. Studies of the muscles of the neck and shoulder, combining external observations and dissections, c. 1509–10. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 137r.

The text refers to the therapeutic practice of bloodletting, which was often prescribed by doctors but executed by barbers. The written lines surrounding the figure indicate which veins should be cut for specific illnesses. In addition, various parts of the body of the figure are labeled with the names of the signs of the zodiac, referring to the astrological context of surgical procedures.

From the way the notes are arranged around the figure or superimposed on it, it is evident that the text is more important. The figure serves merely as a schematic reference to aid the memory. Laurenza also points out that, even though the figure is rendered realistically and is not without artistic merit, it adds no information to the notes about bloodletting in the text. There is no representation at all of veins corresponding to the written instructions on how to cut them.

Leonardo revolutionized this relationship between text and figure in his anatomical drawings by giving priority to the visual image. Even a cursory look through the anatomical folios of the Windsor Collection makes it evident that his main focus is on the image. The accompanying text is secondary, often limited to explanatory captions, and is sometimes absent altogether. Indeed, he believed that his visual anatomical representations were more efficient than any written descriptions. He proudly asserted that they gave “true knowledge of [various] shapes, which is impossible for either ancient or modern writers … without an immense, tedious and confused amount of writing and time.”29 Leonardo’s anatomical drawings were so radical in their conception that they remained unrivaled until the end of the eighteenth century, nearly three hundred years later.

A plate of the anatomical organs of a pregnant woman, created by an anonymous illustrator at the end of the fifteenth century (fig. 6-6), provides another instructive opportunity to highlight the dramatic differences with Leonardo’s anatomical drawings. Again, the text invades the figure, whose schematic anatomical features cannot be understood without the explanatory captions superimposed on them. The contrast with Leonardo’s famous representation of the same subject (see fig. 4-5), created around the same time, is stunning. So is the comparison between the symbolic representation of the fetus in fig. 6-6 with Leonardo’s delicate and totally realistic drawings of the human fetus within the womb (plate 9).

FIG. 6-5. Anatomical figure by anonymous Florentine artist, fifteenth century. Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, Ms. CSP.X.42, folio 66r.

FIG. 6-6. Anatomical organs of a pregnant woman by anonymous illustrator, end of fifteenth century. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Pal. Lat. 1325, folio 349v.

A few years after the Latin edition of the Fasciculus medicinae was published, an Italian edition was printed in Venice with some significant changes to the illustrations. The figures are much more realistic and they are no longer invaded by the text. “All this seems to move in the direction taken by Leonardo,” observes Laurenza, “except for the fundamental fact that Leonardo continues to work within the manuscript culture, innovating it but remaining its prisoner, while the [publishers of the Fasciculus] operate in a new world: that of the print culture.”30

Leonardo was well aware of the great advantages of the printed image for exact replication and rapid dissemination, and throughout his life he was keenly interested in the technical details of the printing process.31 He envisioned that his treatises would eventually be printed, and he insisted that his anatomical drawings should be printed from copper plates, which would be more expensive than woodcuts but much more effective in rendering the fine details of his work. “I beg you who come after me,” he wrote on the sheet that contains his magnificent drawings of the vertebral column (see fig. 6-8), “not to let avarice constrain you to make the prints in [wood].”32 However, the printing of his most finished anatomical drawings—with ultra-fine hatchings and in some cases with added watercolors—would have required highly sophisticated techniques of etching and other innovative techniques that were not available during his lifetime.33

Anatomical Drawings and Dissections

The reversal of the relationship between text and figure is not the only revolutionary aspect of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings. In order to present the features of the human body accurately and realistically—“just as if you had the natural man before you” (see p. 133)—he introduced numerous innovations: drawing anatomical structures from several perspectives; presenting them in “exploded views” to illustrate how the parts of an ensemble (for example, the vertebrae of the spine) fit into one another; showing the removal of muscles in successive layers to expose the depth of an organ or anatomical feature, and so on. None of his predecessors or contemporaries came close to him in such anatomical detail, accuracy, and sophistication.

When he pictured muscles, tendons, and bones, Leonardo’s main intention was always to show how they work together in the movements and activities of the entire body. To achieve this purpose, it was of paramount importance to him to demonstrate the three-dimensional relationships between various structures, so he repeatedly showed them from various perspectives. As he explained,

If you want to know thoroughly the anatomical parts of man, you must either turn him, or your eye, in order to examine him from different aspects; from below, from above, and from the sides, turning him round and investigating the origin of each part; and by such a method your knowledge of natural anatomy is satisfied.34

This passage is part of a long sequence of paragraphs in which Leonardo sets out his ambitious plans for his magnum opus De figura umana (On the Human Figure; see p. 133). Having explained the need for presenting anatomical structures from several perspectives, he then describes how he would do that for each individual part:

Therefore, through my plan you will come to know every part and every whole through the demonstration of three different aspects of each part. For when you have seen any part from the front with some nerves, tendons, and veins that arise from the side in front of you, the same part will be shown to you turned to its side or its back, just as though you had the very same part in your hand and went on turning it round from one side to another until you had obtained full knowledge of what you want to know.35

We do not know how much of this ambitious program Leonardo was able to carry out. But among the two hundred folios of anatomical drawings that have come down to us, there are many in which he demonstrates his technique of showing anatomical structures from different perspectives (for example, figs. 6-7, 6-8, 6-9, and 6-10). Sometimes these different perspectives form such a smooth sequence that they suggest continuous movement, almost like images on a strip of film (see plate 4).

Leonardo’s sophisticated anatomical drawings were based on a large number of dissections of human and animal bodies, which he carried out with the most delicate care and attention to detail, “taking away in its minutest particles all the flesh” to expose blood vessels, muscles, or bones until the corpse’s state of decay was too advanced to continue. “One single body was not sufficient for enough time,” he explained, “so it was necessary to proceed little by little with as many bodies as would render the complete knowledge.”36 And even that long and difficult procedure was not enough to satisfy Leonardo’s high scientific standards. “This I repeated twice in order to observe the differences,” he tells us laconically.

On the same page, Leonardo also gives us a vivid account of the dreadful conditions under which he had to work. As there were no chemicals to preserve the cadavers, they would begin to decompose before he had time to examine and draw them properly. To avoid accusations of heresy, he often worked at night, lighting his dissection room by candles, which must have made the experience even more macabre. “You will perhaps be impeded by your stomach,” he writes, addressing an imaginary apprentice, “and if this does not impede you, you will perhaps be impeded by the fear of living through the night hours in the company of these corpses, quartered and flayed and frightening to behold.”37

It was Leonardo’s passionate desire for scientific knowledge that gave him the strength he needed to overcome his own aversion. His emotional struggle is eerily reminiscent of a celebrated passage he wrote when he was in his late twenties. It is one of the very few passages in the Notebooks where he reveals his emotions, and its poetic language and symbolic nature have led some authors to speculate that it may refer to a childhood memory or a dream:

Drawn by my ardent desire, impatient to see the abundant variety of strange forms created by artistic nature, and having wandered for some time among the dark rocks, I reached the entrance of a great cavern, before which I remained for a moment, stupefied and unfamiliar with such a thing. I folded my loins into an arch, leaned my left hand on my knee, and with my right I sheltered my lowered, knitted brows; and I leaned repeatedly from one side to the other to see if I could discern anything inside. But the great darkness which reigned there did not let me. Having remained thus for some time, two things suddenly arose in me, fear and desire: fear of the menacing dark cave, and desire to see if there was some miraculous thing inside it.38

Leonardo’s anatomical dissections, too, were driven by ardent desire. Overcoming his natural repugnance, he repeatedly entered the dark cave of the dissection room and returned with many “miraculous things” that would forever establish his fame as the greatest anatomist of his time.

In spite of the distasteful conditions under which Leonardo performed his anatomies, he never lost sight of the human dignity of the corpses he dissected. This is evident from his famous account of how, during one of his visits to the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, he met an old man who then died in his presence:

And this old man, a few hours before his death, told me that he was over a hundred years old and that he felt nothing wrong with his body other than weakness. And thus, while sitting on a bed in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, without any movement or other sign of any mishap, he passed out of this life.—And I made an anatomy of him in order to see the cause of so sweet a death.39

Leonardo’s post mortem of the “centenarian” became a milestone in his work and led him to some of his most important medical discoveries (see p. 306). At the same time, the story is a moving testimony to the deep humanity of a great scientist.

In the long passage where he describes his techniques of dissection, Leonardo states that he had “dissected more than ten human bodies,” and when he lived in Amboise in his old age, he told a visitor that he had “made anatomies of more than 30 bodies, male and female of all ages.”40 In addition, Leonardo dissected numerous bodies of animals, which were much easier to obtain, and he often transferred what he learned from these animal dissections to the human body. Laurenza points out that the resulting “hybrid anatomical representations” are often regarded by scholars as inaccuracies and signs of immaturity, but that a different interpretation may also be possible:

These representations certainly reflect the difficulties, in those early years, of carrying out human dissections. However, Leonardo does not conceal the animal origin of his notions … thus emphasizing the animal aspects of the human anatomy.41

What emerges eventually from these conceptual developments is Leonardo’s assured and accurate realization that the human body is an animal body.

The vast corpus of Leonardo’s anatomical studies has been analyzed in impressive detail by several scholars of medical history. In addition to the recent reconstruction and revaluation by Laurenza, my main sources have been two standard volumes: Leonardo da Vinci’s Elements of the Science of Man by Kenneth Keele and Leonardo da Vinci on the Human Body by C. D. O’Malley and J. B. Saunders.42 In the following pages, I can only review the most outstanding of Leonardo’s achievements in anatomy.

Bones and Joints

The human skeleton was, naturally, much easier to examine than the body’s internal tissues and organs, which would have lost their form and structure soon after their dissection. Leonardo’s renderings of bones and joints are among his most accurate, most finished, and most beautiful anatomical drawings. Indeed, they have been praised by Keele as extraordinary, even when compared with today’s anatomical representations:

Of all Leonardo’s achievements those of his drawings of the human skeleton and muscles have perhaps been accepted as the most outstanding. This aspect of his exploration of the human body, supplemented by his unique capacity for presenting movements in visual perspectival form, make his drawings of bones live in a way seldom achieved by modern anatomical illustration.43

A magnificent folio in the Windsor Collection (fig. 6-7) shows Leonardo’s nearest approach to drawing a complete skeleton. In a group of six drawings, several ensembles of bones and joints are displayed from the back, front, and side. The pelvis is shown for the first time in its accurate shape and place, correctly angled in relation to the spine and thigh-bones. The thorax, lumbar spine, and knee joints are shown with remarkable accuracy. According to Keele, “These drawings convey deep understanding of the statics [and] the transmission of weight in the human erect posture.”44

Having demonstrated how the various parts of the skeleton fit together, Leonardo then proceeded to study them individually and in pairs on several other folios. These include studies of the vertebral column, the pelvis and legs, and the arms and hand, as well as the elbow and the knee and ankle joints.45 All of these studies show the relevant bones and joints from several perspectives (front, side, and back) and in several positions: elbows bending and stretching, forearms rotating, legs in standing and kneeling positions—all of them precise analyses of the mechanics of bodily movement.

FIG. 6-7. The human skeleton, c. 1509–10. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 142r.

On the celebrated folio of studies of the vertebral column (fig. 6-8), Leonardo demonstrates with wonderful accuracy how the vertebrae of the spine interlock to form a flexible column. The first drawing on the right (where Leonardo, writing and sketching from right to left, usually starts the page) shows the whole spine from the front. The five sets of vertebrae (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal in modern medical terminology) are clearly marked with letters, and in the text they are correctly enumerated in a little table, adding up to thirty-one in all. In addition, Leonardo notes precisely where the sensory nerves going to the arms and legs emerge from the spinal cord.

FIG. 6-8. The vertebral column, c. 1509–10. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 139v.

The second drawing shows a lateral view of the vertebral column in which the spinal curvature is represented with complete accuracy—a feat unmatched by any other Renaissance anatomist. At the bottom of the page, the spine is depicted from behind, and to the left of this view the seven cervical vertebrae are shown with such precision that they can easily be identified by a modern medical practitioner. In addition, Leonardo depicts the first three cervical vertebrae in an “exploded view” in which the complex interlocking mechanisms of the joints, marked with letters, are clearly recognizable.

These drawings represent not only a tremendous scientific achievement but are also artistic masterpieces. Leonardo’s precise renderings, together with his mastery of perspective and of light and shade, combine to convey a sense of complexity, elegance, and beauty unequalled in contemporary or modern scientific illustrations. No wonder he allowed himself a rare outburst of pride at the bottom of the page, stating that his presentations of the vertebrae “will give true knowledge of their shapes, knowledge that neither ancient writers nor the moderns would ever have been able to give without an immense, tiresome, and confused amount of writing and time.”

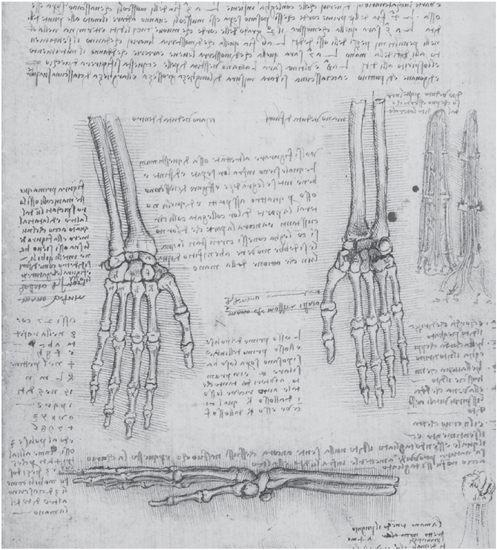

In another beautiful set of drawings Leonardo presents his studies of the bones of the hand (fig. 6-9), employing delicate hatchings, two shades of brown ink, and wash over traces of black chalk. These studies were the first to show the bones of the wrist and hand accurately, displaying them from the front, the back, and from both sides. All bones are clearly labeled and enumerated in the accompanying text. In two sketches on the right margin, the bones of the fingers are covered by the flexor and extensor tendons, arteries, veins, and nerves—all labeled with letters and identified in the text below. The paragraph at the bottom of the page is devoted to a description of the movements of the hand at the wrist.

The text at the top of the page makes it clear that Leonardo intended this set of studies to be merely the first of a series of eight systematic demonstrations of the hand:

The first demonstration of the hand will be made of the bones alone. The second of the ligaments and the various chains of tendons which bind them together. The third will be of the muscles that arise from these bones; [the fourth and fifth] of the … cords that move all the fingers.… The sixth will demonstrate the nerves that give sensation to the fingers of the hand. The seventh will show the veins and arteries that give nourishment and [vital] spirit to the fingers. The eighth and last will be the hand clothed with skin, and this will be illustrated for an old man, a young man, and a child.46

FIG. 6-9. Studies of the bones of the hand, c. 1509–10. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 143v.

On another folio, he envisages an even larger set of forty demonstrations of the hand, concluding his long description with the ambitious statement:

And thus in the chapter on the hand you will give forty demonstrations; and you should do the same with each limb. And in this way you will give full knowledge.47

We do not know how much of this grandiose project Leonardo was able to execute, since many of his anatomical drawings were lost. The Windsor Collection contains a few more detailed studies of the hand, as well as similar studies of the foot, again with all of its bones enumerated and shown in perfect anatomical shapes.48 However, Leonardo himself acknowledged that it was unlikely that he would ever complete his anatomical studies in the systematic manner he envisaged. “In these I have been impeded,” he wrote wistfully, “neither by avarice or negligence, but only by time.”49

Muscles and Tendons

In Leonardo’s scheme of systematic anatomical demonstrations “from within,”50 the muscles and tendons are displayed in the second and third sets of dissections, after the demonstrations of the bones. In this endeavor, his goal was always to understand how muscles, tendons, and bones work together to bring about the movements of the body. As Keele puts it, “Leonardo was, one may say, dissecting the movements of the human body rather than a motionless cadaver.”51

“There are six things that come together in the composition of movements,” Leonardo explains in his Anatomical Studies, “that is, bone, cartilage, membrane, tendon, muscle, and nerve.”52 On another nearby page, he describes the nature and the functions of this sequence of anatomical structures in more detail:

Tendons are mechanical instruments … which carry out as much work as is assigned to them [by muscles]. Membranes are joined to the flesh, being interposed between the flesh and the nerve…. Ligaments are joined to tendons and are a kind of membrane which bind together the joints of bones, and are converted into cartilage. They are as numerous in each joint as are the tendons which move the joint and as the tendons opposite, which come to the same joint. And such ligaments are all joined and mixed together, aiding, strengthening, and balancing one another.53

These descriptions are remarkably accurate. The terms used by Leonardo are still used in medical science today.*

Implicit in the last two sentences of Leonardo’s description is the recognition that pairs of antagonistic muscles keep the body in balance. On another folio, he describes these “pairs of muscles which are in opposition to one another” in more detail and discusses their importance for the maintenance of body posture.54 Medical historian Sherwin Nuland has noted that the action of muscle groups acting reciprocally with antagonistic groups was not recognized again until the early twentieth century.55

In the long passage where Leonardo sets out his plans for multiple sets of dissections, he also discusses the tremendous difficulties encountered in dissecting the soft tissues of the body. He vividly describes “the very great confusion that results from the mix-up of membranes with veins, arteries, nerves, tendons, muscles, bones, and blood which itself dyes every part the same color; and the vessels emptied of this blood are not recognizable because of their diminished size; and the integrity of the membranes is broken in searching for those parts which are enclosed within them.”56 In view of the delicate and ephemeral nature of these tissues in the absence of preservatives, the clarity and accuracy of so many of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings are all the more astounding.

To demonstrate the actions of muscles and tendons as “mechanical instruments,” Leonardo developed an effective method for converting complex muscular patterns into simplified geometrical diagrams.57 To begin with, he identifies the “central line” of action (known today as the “line of pull”) for muscles of various shapes. Then he introduces a highly ingenious technical innovation: “Make a demonstration of the fine muscles by using rows of threads,” he explains on the folio showing the anterior muscles of the leg (see fig. 4-7). “Thus you will be able to represent one upon the other, as nature has placed them; and thus you will be able to name them according to the part they serve … And having given such knowledge, you will draw alongside this the true shape, size, and position of each muscle.”58

La sapienza è figliola della sperienza. (Codex Forster III, folio 14r)

Wisdom is the daughter of experience.

He makes a special point of drawing cords and not just lines: “When you have drawn the bones of the hand and wish to draw on this the muscles which are joined to these bones, make threads instead of muscles. I say threads and not lines in order that one should know which muscle goes below or above another muscle, which cannot be done with simple lines.”59 This note is found on the folio showing studies of the mechanisms of the hand that illustrate this technique (see fig. 4-2). The passage of the five flexor tendons under the transverse carpal ligament is clearly visible.

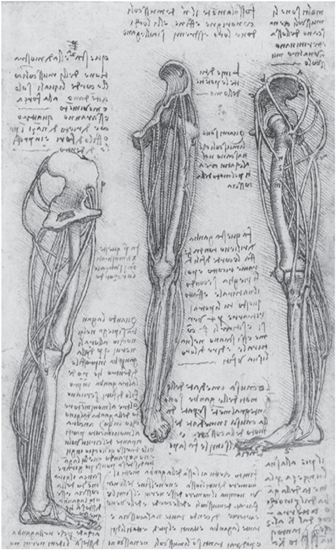

Finally, having replaced muscles and tendons by cords in some of his drawings, Leonardo proposes to construct a physical model of the resulting diagrams of muscular forces. He illustrates this last step of his technique with the muscles of the leg: “Make this leg in full rounded relief [that is, like a statue] and make the cords of tempered copper wires, and then bend them according to their natural form. After doing this you will be able to draw them from four sides, and to place them as they exist in nature and speak about their functions.”60 On the folio that contains these instructions (fig. 6-10), the resulting wire diagram of the leg muscles is shown from three sides.

Medical historians O’Malley and Saunders have identified a number of leg muscles in these cord diagrams, but they also point out that the drawings contain many inaccuracies.61 Nevertheless, Leonardo’s whole approach to the mechanical analysis of complex muscular patterns shows an unprecedented level of scientific and mathematical reasoning.

In his studies of the human muscular system, Leonardo concentrated his greatest efforts on the muscles of the shoulder and arm, the arm and hand, and the leg and foot. These are also the areas of myology (the study of muscles) in which he produced his most beautiful illustrations. The Windsor Collection contains about a dozen folios with studies of the shoulder region, among them the celebrated rotated views of the muscles of the shoulder and arm (see plate 4). This folio is preceded in the Collection by one showing another four sequential views.62 The two folios together present a continuous series in which the body is turned through 180 degrees, from front to back (when viewed from right to left in the direction of Leonardo’s writing and sketching). The result is an almost cinematographic display of muscle action during the rotation of the shoulder. In the drawings, various muscles are labeled with letters and described in the accompanying text, and even those without letters can easily be identified by a modern anatomist owing to their accurate representation.63

FIG. 6-10. Cord diagrams of the muscles of the leg, c. 1509–10. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 152r (detail).

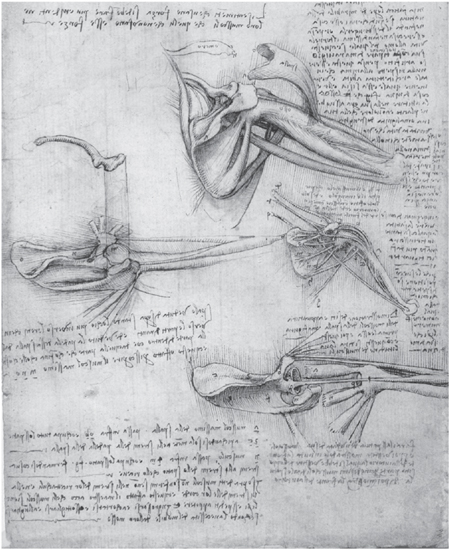

From a scientific point of view, Leonardo’s studies of the deep structures of the shoulder are perhaps even more remarkable. In the four drawings shown in figure 6-11, for example, he employs several of his innovative graphic techniques. In the top drawing, the deltoid and trapezius muscles are lifted off to expose the underlying deep structures of the shoulder joint, all of which are so clearly rendered that they can easily be identified.64 In the left drawing, the collar-bone is separated in an exploded view to show how it forms a joint with part of the shoulder blade. In the drawing at the bottom, all the muscles have been cut away so as to clearly expose the deep structures. The middle drawing on the right, finally, is a cord diagram of the shoulder muscles demonstrating their pull lines.

With his skillful use of these graphic techniques, Leonardo is able to demonstrate the spatial extensions and mutual functional relationships of the complex anatomical structures of the shoulder with compelling clarity. The lines of forces, parts labeled with letters, and other parts joined by guide lines make these drawings almost like a set of mathematical diagrams—geometric representations of functional anatomical relationships.

One of Leonardo’s most finished studies of bone structures, drawn in the same exquisite style as his studies of the bones of the hand (see fig. 6-9), is his demonstration of the rotation of the arm (plate 3). The principal purpose of this series of five drawings is to demonstrate the mechanisms by which the palm of the hand is turned upward and downward, “toward the sky” and “toward the earth,” as Leonardo puts it. It is one of Leonardo’s many investigations of how bodily movements are generated by the actions of muscles and tendons.

FIG. 6-11. Deep structures of the shoulder, c. 1509–10. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 136r (detail).

The top drawing shows the outstretched arm with the correct proportional lengths of the bones. The biceps, the principal object of this study, is shown with its two heads joining halfway down the humerus (the bone of the upper arm). The muscle is depicted without its tendon, but the tendon’s point of attachment to the radius (the smaller of the two forearm bones), just below the elbow, is clearly shown as a protruding band. The second drawing presents an exploded view in which the shape of the shoulder joint and the interlinking of the bones forming the elbow joint are demonstrated with great precision.

Leonardo discovered that the biceps not only bends the elbow but helps turn the palm upward by rotating the top of the radius. This is demonstrated in the third drawing. The two heads of the biceps are shown once more at their origin, and they are cut at point “b” (“d” in Leonardo’s mirror writing) just before joining the tendon. The tendon’s attachment to the radius is shown again, labeled with the letter “a” (“^”). In this position, known as supination by modern anatomists, the two bones of the forearm, radius and ulna, lie parallel.

When the palm is turned downward in the position known as pronation, the rotated radius crosses the ulna. This is clearly demonstrated in the fourth drawing. Because of the crossing of the two bones, the forearm is slightly shortened, as Leonardo explains correctly in the accompanying text:

The arm which has two bones interposed between the hand and the elbow will be somewhat shorter when the palm of the hand faces the earth than when it faces the sky, when a man stands on his feet with his arm extended. And this happens because these two bones, in turning the palm of the hand to the earth, become crossed.65

In the last drawing of this study, Leonardo analyzes the muscles that produce pronation. The biceps is now presented together with its tendon, and the so-called pronator muscle, which rotates the radius in the opposite direction to the biceps, is also shown. The pronator is accurately rendered as it originates at the end of the humerus (in front in the drawing) and runs like a strap to the top of the radius.*

It is worth noting that Leonardo accurately demonstrates the actions of the biceps and pronator muscles in these drawings but does not describe them in the accompanying text, confident that his visual demonstrations were more effective than any words could be.

On a double folio in the Windsor Collection we find another celebrated anatomical study, showing the anterior muscles of the leg and foot (see fig. 4-7). Executed in three shades of brown ink and chalk with copious blocks of text arranged beautifully around it, the drawing shows a level of sophistication and elegance rarely, if ever, achieved in modern anatomical illustrations.

In the drawing, the muscle bellies of the short extensor muscles on the front of the foot (labeled a, b, c, d) are admirably rendered, and so are the long extensor muscles on the front and side of the shin (labeled f, n, r, s, t), which pull the foot and toes upward. All in all, about a dozen muscles can readily be identified.66 In the text, Leonardo offers detailed descriptions of the synergistic actions of these muscles in producing the complex movements of the foot. In the lower right corner of the double page, almost hidden in the text, there is an exquisitely accurate drawing of the way the extensor tendon is inserted into the back of the big toe. According to O’Malley and Saunders, “nothing approaching such detail is to be found until comparatively recent times.”67

Muscles and Nerves

In his studies of the body in motion, Leonardo traced various bodily movements back from the bones and joints, and the tendons attached to them, to the contraction of specific muscles; he also investigated the nerve impulses that trigger muscle contractions, following them through the motor nerves and the spinal cord into the brain, where he believed he had located the seat of the soul. His concise summary of this pathway of the body’s motor forces is worth repeating (see p. 212):

Spiritual movement, flowing through the limbs of sentient animals, broadens their muscles. Thus broadened, these muscles become shortened and draw back the tendons that are connected to them. This is the origin of force in the human limbs…. Material movement arises from the immaterial.68

The investigation of the nervous system was the last step in Leonardo’s systematic demonstrations of the body in motion. Chronologically, however, it was where he began his anatomical work. I have discussed Leonardo’s detailed explorations of the cranial nerves and his neurological theory of perception and knowledge in my previous book.69 To summarize, he asserted that the sensory nerves carry all sense impressions to the brain, where they are selected and integrated before entering consciousness at the central cerebral ventricle (the “seat of the soul”) to be judged by the intellect, influenced by the imagination, and then partly committed to memory.

Leonardo made a distinction between sensory and motor nerves, and he followed the nerve impulses for voluntary movement from the brain down the spinal cord and through the peripheral motor nerves to the muscles, tendons, and bones. His elaborate explorations of the anatomy of the nervous system began around 1489, when he was in his mid-thirties, and reached their peak about twenty years later, during the time he also produced the superb studies of muscles and bones I have just discussed.

Leonardo had an integrated view of the soul, seeing it both as the agent of perception and knowledge and as the force underlying the body’s formation and movement.70 The nervous system, accordingly, integrated all the movements and activities of the body. The sensory nerves carried sense impressions to the soul, and the motor nerves transmitted forces from the soul to the limbs, where the nerves, “having entered into the muscular fibers, command them to move.”71

In a schematic drawing produced around 1508, Leonardo demonstrated how all these nerves are interconnected. It shows the entire nervous system: the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nerves to the trunk, the arms, and the legs (fig. 6-12). He presented this scheme from the front and from the left side. Between the two figures there is an explanatory note: “Tree of all nerves; and it is shown how all these have their origin from the top of the spinal cord, and the spinal cord from the brain.”72 A small sketch, also between the two figures, shows another diagrammatic outline of the nervous system. The note underneath reveals that the two figures shown on this folio were only the beginning of a much more ambitious project: “In each demonstration of the entire extent of the nerves, draw the external outlines, which denote the shape of the body.”73

We do not know whether Leonardo ever carried out his plan, but since he produced an integral view of the skeleton (see fig. 6-7) and one of the internal organs (see fig. 4-5) around the same time, it is not unreasonable to assume that he also presented the entire nervous system on a single folio. At any rate, no such drawing has come down to us. However, the Windsor Collection contains numerous detailed studies of various parts of the nervous system.

FIG. 6-12. “Tree of all nerves,” c. 1506–8. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 76v.

The early studies were largely based on dissections of animals, which were then projected onto human outlines. But during the period when he drew his “tree of nerves,” Leonardo produced several accurate studies of the cranial and intercostal nerves, as well as the nerves of the shoulder, hand, and leg. Among them is a composite drawing (fig. 6-13) based partly on animal dissections, in which the curvature of the spine, the intercostal muscles, and the pelvic vessels and nerves are clearly and beautifully rendered.74

FIG. 6-13. Study of the curvature of the spine, the intercostal muscles, and the pelvic vessels and nerves, c. 1506–8. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 109v (detail).

One area that fascinated Leonardo for two decades is the so-called brachial plexus, a complex bundle of nerves that forms the neural connections between the neck and the nerves of the arm. His early studies of this nerve complex, based on dissections of monkeys, date from 1487 and are among his very first anatomical drawings. The studies reached their climax more than twenty years later with a drawing that accurately represents the brachial plexus in all its complexity (fig. 6-14).

Above the main drawing on this folio, Leonardo wrote “del vecchio,” indicating that the dissection was performed on the “old man,” the centenarian at Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. The study correctly depicts the brachial plexus as being formed by the lower four cervical nerves and the spinal nerve emerging from the first thoracic vertebra. Its extension from the lower part of the side of the neck to the underarm is clearly shown, and so is the complex pattern that arises as the five nerves repeatedly divide, merge with one another, and reunite. According to Kenneth Keele, “this whole map of the brachial plexus should be evaluated as a major discovery in Leonardo’s [anatomical] explorations.”75

FIG. 6-14. The brachial plexus, c. 1508. Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies, folio 57v (detail).

After five hundred years, Leonardo’s anatomical drawings have lost nothing of their splendor. We still admire their amazing accuracy and sophistication, and we are spellbound by their beauty. They are an enduring testimony to his genius, as both a scientist and an artist.