9 AGILE LEADERSHIP

It isn’t enough for just teams to understand Agile; their leaders, managers and organisation must also become Agile

We already know that working in an Agile way requires teams to think and behave in different ways, but this is true for managers and leaders too. In fact, some of the changes they must make are even more profound and uncomfortable than those of their teams. Yet, this is not always acknowledged and not always discussed. It is easy to read a book on Agile or attend a training course as a manager and leave assuming that all the changes will be in how other people act. This failure to acknowledge the significance of good Agile leadership in the success of any Agile endeavour is important – it is a key reason why many Agile teams struggle or fail.

So, why is this the case? Why don’t leaders see that adopting Agile also requires a shift in their mindset? There are, of course, many reasons, but an important one is that the kind of cultural shift required of leaders is hard and it is uncomfortable. It requires rejecting decades of practices, beliefs and behaviours that don’t seem to be obviously broken. These same behaviours are often the things that are sought out when promoting and appointing leaders, therefore perpetuating the cycle.

Yet when we look at where those established management practices came from, we can see that they originate in an environment that is very different from the VUCA world we find ourselves in today. The work is different, the challenges are different, the people are different. When things change, we ought to respond to those changes – and that includes how we lead and manage.

This chapter explores some of these factors. It will help to explain the different styles of leadership and how we can change to better enable Agile behaviours in our teams, and why these changes make our teams more effective. We will briefly introduce several leadership ideas and theories, but for more thorough coverage we recommend the references.

This chapter will cover:

- Why we lead and manage the way that we do.

- What is different in Agile leadership.

- How leadership influences the ways Agile teams behave.

Most organisations are led and managed in similar ways, irrespective of their sector, purpose or history. There is a top level that sets direction and strategy for the rest of the organisation to implement. This top level wants to ensure that their instructions are adhered to, so they implement a management and oversight structure to provide that assurance. This management structure usually involves setting out what needs to be done at the next layer down and monitoring that this happens. There are usually several layers of control necessary to be able to break down the tasks to the level at which the work is assigned to a person. We can trace this approach back to the late 19th century and the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor.

Taylorism

While managing the factory floor of a steelworks in the US, Taylor noticed that, when left to their own devices, the workers would take different approaches to the same task. The difference in productivity was less to do with the hard work (or laziness) of the workers and more to do with the lack of a system that described the most efficient approach for each task. He believed there was ‘one best way’ to perform each task and set about identifying and describing this. He broke the tasks down to their simplest steps and directed the workers to follow them to the letter. He selected and trained the workers for the tasks and followed a principle whereby the managers performed the thinking and the workers focused on performing the task.

His impact was profound. By splitting the work into detailed, specified tasks, focusing workers on a small set of tasks each and rigorously monitoring them, he proved repeatedly that this would improve productivity. In 1911 he published his findings in his book, The Principles of Scientific Management,141 which has gone on to influence virtually every large organisation in the world with its premise that management is a discipline, that managers are separate from workers and that managers think and workers do.

Meanwhile, in Europe, Henri Fayol was also concluding that strong management practices were key to predictability and efficiency. Learning from his experiences in mining, in his 1916 book, Administration Industrielle et Générale,142 he defined five functions of management – planning, organising, commanding, controlling and coordinating – underpinned by 14 principles of management. This encouraged organisations to seek to specialise and control their workforce to become more productive.

Where Taylor drew his conclusions in a steelworks environment, Henri Fayol reached similar conclusions in mining and Henry Ford famously adopted the production line for motor car manufacture. It appeared that this top-down, management-centric approach worked in multiple sectors, so it isn’t surprising that it caught on.

What these approaches have in common is that they focus on the perspective of the managers and the business. They assume that workers are there to be controlled and are not a sentient part of the system; the managers do the thinking because the workers aren’t capable of it. This leads to several other assumptions made of workers that Douglas McGregor identified in his 1960 work, The Human Side of Enterprise,143 and described as Theory X.

Theory X managers believe that:

- The average person prefers to be directed, to avoid responsibility, is relatively unambitious and wants security above all else.

- The average person dislikes work and will avoid it if they can.

- Therefore, most people must be forced with the threat of punishment to work towards organisational objectives.

This theory fits well with the recommendations of Taylor and Fayol and may well be true for the work environments they created: workers performing repetitive, low skill tasks dictated to them by managers and held to strict criteria.

However, McGregor believed that there was an alternative theory that was far more suited to the kinds of work that were emerging in the later 20th century; work that is less certain, where workers need to apply some thought to their work. We call this ‘knowledge work’, a term coined by Peter Drucker in 1959 and described in his 1967 book, The Effective Executive.144 McGregor describes this alternative as Theory Y.

Theory Y managers believe that:

- Work can be as natural and as enjoyable as play.

- People don’t require external control or threat of punishment to apply self-control and self-direction to achieve organisational objectives.

- Commitment to the objective is in itself part of the reward, not just achieving the goal.

- People usually accept and often seek responsibility.

- Most people have the capacity to use a high degree of imagination, ingenuity and creativity to solve problems.

This is a wholly different approach to leading and managing than Theory X. In fact, it is such a paradigm shift that many managers cannot even contemplate it being true. When we look at how many organisations are currently structured – their HR policies and processes, how they task or allocate work, their oversight and governance mechanisms, the organisation of their teams and team management – we can see a clear skew towards Theory X assumptions. This is despite them being based on observations more than 100 years old, and from industries that are completely different from today’s knowledge-worker dominated environment – and that’s before we even think about how well suited they are to the VUCA environment we described earlier.

WHAT IS AGILE LEADERSHIP?

Until this point, we have used the word manager a lot. This is intentional. The dominant focus of leadership in the past has been to manage the work, implying that the jobs that need doing are well known and the role of management structures and managers is to check that they are being done and being done properly. This is reinforced by titles such as managing director, general manager, management committees, project manager and many more. When we call somebody a manager, we are priming them to expect to manage and priming those around them to be managed.

That is not what is required in Agile organisations. In fact, the complete opposite is true. The people best placed to make decisions on what needs to be done are the people doing the work, not those above or around them. Therefore, good Agile teams don’t have or need managers. However, they do require leadership, and good leadership is a prerequisite for being able to pivot away from a culture built on the manager-centric ethos of Taylor and Fayol.

The good news is that good Agile leadership is not a million miles away from the leadership being advocated by management experts today. As we will see later in this chapter, psychologists, military historians, naval captains and other progressive leaders are describing approaches that fit perfectly with Agile leadership, although none of them reference the Agile Manifesto nor profess to be Agile experts.

We can also find good examples of Agile leadership from history. In Chapter 8 we quoted German Field Marshal von Molkte, who served in the Prussian army in the 1800s. His view on what constitutes an order is a perfect example of Agile leadership. He said: ‘… an order should contain all, but also only, what subordinates cannot determine for themselves’.145 In other words, give the team enough, just enough, information to achieve the desired outcome, letting them work out for themselves everything they possibly can.

Agile leadership begins with the team. Valuing the left-hand side of the Manifesto means trusting individuals, relying on collaboration more than paperwork and processes, and assuming that any decision might need to be revisited if things change. This means that a classic top-down cascade of ideas and tasks cannot work. Instead, we move as much decision making as we can into the team and defer decisions until as late as possible.

Working out which decisions can be moved into the team, and how late decisions can be deferred, is the role of the leadership. There will still be some decisions the team can’t or shouldn’t make, and some decisions that need to be made earlier than we may prefer. The challenge is balance – doing just enough, just in time.

Creating the right environment to optimise Agile leadership requires leaders to adopt a different mindset from what many are used to. The traditional approaches, still wedded to Taylorism and Theory X assumptions, don’t allow Agile teams to thrive, and in many cases will conspire to do harm and prevent success.

Some leadership shifts are simple. In David Marquet’s book, Leadership Is Language,146 he explains why what you say can have tremendous impact on your teams. For example, he suggests saying ‘What am I missing?’ rather than ‘Does that make sense?’ or ‘On a scale of 1 to 5, how useful would it be for me to come on site?’ rather than ‘Tell me if you need me to come over.’ This changes the question into a request for information that requires the other person to think before answering, involving them more in the decision and making it more likely to elicit useful and honest answers.

In this section two models are explained that help to describe the kinds of mindset shift necessary to become an Agile leader.

Become a corporate rebel

In January 2016, Joost Minnaar and Pim de Morree quit their jobs and set out around the world to seek out inspirational leaders and interview them. Over the next few years, they spoke to people in large and small organisations, in the public and private sectors delivering services, manufacturing, healthcare, entertainment, in fact almost any type of business you would care to imagine. They document their experiences in their book, Corporate Rebels, and on their website.147

What makes the inspirational people they meet special is that they are doing things differently from their peers. In many cases, radically differently: some allow their staff to set their own salary, others have no expenses policies, others have extreme approaches to innovation and experimentation. But they also have things in common. Through their research, Joost and Pim identified eight trends148 that separated these bold, innovative and pioneering workplaces from the norm. These eight trends also describe what it means to be an Agile leader. They are described in a similar way to the Agile Manifesto, as a journey from one mindset to another:

- From profit to purpose and values.

- From hierarchical pyramids to a network of teams.

- From directive leadership to supportive leadership.

- From predict and plan to experiment and adapt.

- From rules and control to freedom and trust.

- From centralised authority to distributed authority.

- From secrecy to radical transparency.

- From job descriptions to talents and mastery.

Much like the Agile Manifesto, history, experience, dogma and discomfort will keep many leaders towards the status quo. It can be uncomfortable and lonely to be moving towards the right of this set of values, but, as the Corporate Rebels have found, those who make the shift are rewarded.

Three key mindset shifts

In his book, The 6 Enablers of Business Agility,149 Karim Harbott explains that adopting the latest Agile tools and practices won’t be enough to make your organisation Agile; there are six key enabling factors that you must focus on to become a high-performing Agile organisation: leadership, culture, structure, people, governance and ways of working, and for leaders there are three key mindset shifts required. Making these changes is critical in enabling the environment we describe in the rest of this chapter. The three mindset shifts are shown in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Three key mindset shifts for Agile leaders

Mindset shift 1 | Focus less on the work and more on the culture. |

Mindset shift 2 | Decentralise as much of the decision making as possible. |

Mindset shift 3 | Encourage and support the growth and development of those around you. |

While these mindset shifts may not appear all that profound, we frequently see leaders (and managers) in so-called ‘Agile’ organisations do the opposite. We see a focus on outputs, decisions referred upwards and personal development left to the individual to manage in whatever spare time they can find.

SIX LEADERSHIP OUTCOMES

Agile leadership can be broken into broad leadership outcomes. These are distinct things that Agile leaders should seek to achieve. They are shown in Figure 9.1 and we will explore each of them in the following sections.

These six outcomes are not independent of one another. They are different perspectives and lenses on the same thing: how to create high-performing teams. Focusing on any of them should bring some improvement but, since they reinforce one another, focusing on them all will bring the best results.

Servant leadership

The term ‘servant leadership’ was first coined by Robert Greenleaf in his 1970 essay ‘The Servant as Leader’,150 and was inspired by reading Hermann Hesse’s The Journey to the East.151 In the story, Leo is the servant to a group of travellers, yet when he disappears the group falls into disarray and they have to abandon the journey – it is only sometime later that the narrator discovers that Leo was actually the head of a noble order, he was its guiding spirit and a great leader. The group had been completely unaware of Leo’s status, had assumed he was a mere servant and they only made the progress they did because of Leo’s influence and wisdom. Greenleaf used his coined term to describe a better way of leading than traditional command and control. In his essay, he says:

The servant-leader is servant first – as Leo was portrayed. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. That person is sharply different from one who is leader first, perhaps because of the need to assuage an unusual power drive or to acquire material possessions. For such it will be a later choice to serve – after leadership is established.

A servant leader is a low ego leader. They are not seeking their own success and recognition, they are seeking success and recognition for their team first. This is how an Agile leader should behave.

They should seek to serve first, to help their teams become the best they can be, to allow them to take decisions, make mistakes and learn, for the team to feel ownership of the problem and connection to the purpose. They should identify and remove blockers to the team’s progress. They should celebrate success as the team’s success, encouraging and championing them. They encourage the team to reflect on their progress, to identify ways they can grow and to use each task or activity as an opportunity to learn and improve.

Servant leadership shares many attributes with good coaching. Developing and using coaching skills – asking powerful questions, actively listening, focusing on future goals – will help to develop good servant leadership behaviours.

When the team needs guidance or direction, the Agile leader gives them just enough guidance to allow them to proceed once more and just enough information to allow them to start making their own decisions again. They involve the team in decisions and strategy, helping them to understand the bigger picture and their place within it.

An Agile leader’s first instinct is to step back; to trust that the team knows what they are doing and will make the best decisions. This is an uncomfortable and unfamiliar place for many leaders. It can trigger feelings of inadequacy and a reduction in status – after all, if the team is doing all the work, what role does the leader have now? It is tempting to want to step in, particularly if you know the answer or can think of a better way, but the best way to improve and develop is from within. Teams make more progress when they identify their own improvements.

Psychological safety

In 2012, when Google set out to identify what makes an ideal team, they expected that their research (codenamed Project Aristotle152) would confirm that putting the best and brightest people together would be important, as would ensuring that the team members were from similar backgrounds and got on well with one another; however, that wasn’t what they found.153 Who was on the team didn’t seem to matter. Instead, what was more important was how the team worked together. They identified five aspects that were common in high-performing teams. The last four were dependability, structure and clarity, meaning, and impact, but the most significant and important aspect was that the team exhibited psychological safety. They described psychological safety as:

[A]n individual’s perception of the consequences of taking an interpersonal risk or a belief that a team is safe for risk taking in the face of being seen as ignorant, incompetent, negative, or disruptive.

In a team with high psychological safety, teammates feel safe to take risks around their team members. They feel confident that no one on the team will embarrass or punish anyone else for admitting a mistake, asking a question, or offering a new idea.

The phrase ‘psychological safety’ was coined by Amy Edmondson in 1999 and described in her 2018 book, The Fearless Organization.154 Creating the conditions for psychological safety requires trust, openness, curiosity about our colleagues and a non-judgemental culture. It also requires an absence of fear.

Fear holds us back from being innovative and creative and even from contributing to discussions and collaborating with our colleagues. There can be many sources of fear – for instance, some people fear public speaking or running workshops – and even for those who take public speaking in their stride, expecting a hostile audience or being in a new venue can turn a safe environment into a fearful one.

Creating an inclusive environment is also critical. When people can be themselves at work, they have more capacity to devote to do their best work. This doesn’t just mean that we should not tolerate discrimination, however slight, it also means that people should be comfortable being themselves at work and not be fearful of how their colleagues would react to their sexuality, background, education or anything else. When we hide things from our colleagues because we are worried about the consequences, it consumes mental capacity that we can’t devote to other things.

A consequence of a cognitively diverse team is that different opinions, experience and ideas cause challenge. Psychologically safe teams disagree and challenge one another, but they do this in a kind, helpful and constructive way. They provide ‘tactful challenge’.155 Having psychological safety doesn’t mean everything needs to be ‘nice’. A culture of nice is not a good thing as it leads to people trying to avoid conflict, sugar-coating issues and hiding mistakes. Being nice isn’t the same as being kind. Instead, we want teams focused on the same goal and constructively using challenge to result in innovation, creativity and ultimately better solutions.

The SCARF model

David Rock created the SCARF model156 to describe five domains of human social experience (see Table 9.2) that can trigger the brain’s fight or flight response in much the same way we evolved to detect danger from tigers in prehistoric times. Perceiving an increase or decrease in these domains triggers our brain’s limbic system to respond, depleting energy from the rest of the brain. The problem is that these five domains are easy to find in the workplace and can easily become threats.

Anything that decreases these domains can compromise psychological safety, while things that increases them can help to create psychological safety.

Agile leaders encourage and facilitate psychological safety in their teams. They create space for team members to get to know each other at a deeper level, and understand the similarities and differences that combine to make each team unique, even if the overt skills and job titles are the same. They become comfortable with exposing weaknesses and learning from failures and experiments. They encourage tactful, kind challenge and maximise opportunities for feedback. Overall, they treat people as people, leading with compassion and consideration.

Table 9.2 The SCARF model

Status | our sense of relative importance to others |

Certainty | our ability to predict and be certain of the future |

Autonomy | our sense of control over events |

Relatedness | our sense of safety with others – friends not foes |

Fairness | our perception of fair exchanges between people |

Intrinsic motivation

One of the secrets of a high-performing team is that its members are motivated to do good work. The role of leaders is to create the optimal conditions for motivated people. The source of motivation can come from internal or external stimuli – creating intrinsic or extrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation is where we do something because we want to. Our internal satisfaction is enough of a driver. Extrinsic motivation is where we do something to gain a reward or avoid a punishment – this is what most classic management approaches assume will create higher performing people, so we see policies such as bonuses, targets, stack-ranking performance assessments, on-target earnings, commissions, employee of the month and so on.

In a study of motivation, Daniel Pink discovered that for the types of knowledge work we do today, not only is intrinsic motivation a better way to create high-performing individuals and teams, but extrinsic motivation (such as bonuses for completing a task quicker) can actually lead to poorer performance. This finding was so profound and paradigm shifting that he called his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us.157

Pink goes on to uncover what exactly intrinsic motivation means and describes three key elements that are necessary for highly motivated people and teams – once the basic hygiene factors, such as having enough pay to live on and a nice-enough working environment, are good enough to not be demotivators. Those three elements are: autonomy, mastery and purpose, as shown in Table 9.3.

Creating environments that maximise these three factors can make leaders feel uncomfortable. Increasing autonomy usually means allowing the team to make decisions that used to be made by others, such as managers or senior practitioners. Creating conditions for mastery and continuous improvement means expecting people to push themselves, work outside their comfort zone and to do new work they haven’t done before. This can feel riskier than tasking the team with work you are certain they can do. Sharing the overall purpose can feel like an unnecessary distraction for the team, particularly when their tasks are clear. However, for knowledge work in a VUCA world, this discomfort in leaders is essential for teams to succeed.

Table 9.3 Factors that drive intrinsic motivation

Autonomy | The ability to have control over your life and work; to have choices and take decisions on what to do, when to do it and with whom. Autonomy and freedom motivate us to think creatively and to experiment. |

Mastery | The desire to improve; to be challenged and to get better at your chosen craft. |

Purpose | Working towards a meaningful and purposeful goal. The knowledge of how your work fits in to a bigger picture. |

Agile leaders have to overcome this discomfort, to seek ways to provide teams with autonomy and adopt a position where the default response to any decision is for the team to make it. One way to easily increase autonomy is to increase the level of tasking. Let teams solve bigger problems with more opportunity to consider options and make decisions. This creates more opportunities for mastery by making it easier for the team to vary their level of challenge. This also requires the team to be willing and competent to make decisions themselves, which isn’t the case for all teams.

The third element of intrinsic motivation – purpose – ought to be easier for Agile leaders to provide, yet it is often overlooked or the team is assumed to know it already. To test this, why not ask the team what the purpose of the product is and see how similar the answers are? When we have done this, the range of answers is staggering and there is usually at least one person who says they aren’t really all that sure.

JFK AND THE JANITOR

There is a well-known story that exemplifies the effect of connecting a person to the purpose of their work.

The story goes that when JFK first visited NASA in 1961, he encountered a janitor carrying a broom. He approached him and said: ‘Hi, I’m Jack Kennedy. What are you doing?’

The janitor replied: ‘Well, Mr President, I’m helping put a man on the moon.’

Bringing the purpose and impact of the work to life for the team is an important role for an Agile leader. This is why the customer collaboration value is so important – when we collaborate with our customers, we understand what our work means to them. The easiest way to do this is for the work of the team to have a clear and direct connection to the purpose. For some organisations that is easy; but it isn’t always clear, especially when your team isn’t directly connected to the end customer or the organisation’s core purpose. However, there are still things that Agile leaders can do to provide that connection. Consider things such as objectives and key results (OKRs), customer journeys or asking senior leaders to come and explain to the team how they value the work they are doing.

The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) is the part of the UK Government responsible for cybersecurity advice and support. Their stated purpose is ‘Helping to make the UK the safest place to live and work online.’ It is easy to see how a team in the NCSC can directly connect their work to that high-level purpose.

Trusted, empowered people

The first value in the Agile Manifesto is about valuing individuals and interactions over processes and tools and requires trust and the assumption of noble intent. Many organisations ask managers to fear the worst of their people. They administer processes designed to prevent bad behaviour with approvals, monitoring and oversight. Consider expenses policies: in most companies, these run to many pages, with limits, exclusions, approvals and sanctions.

Netflix explicitly states that they value ‘people over process’158 and prove it with an expenses policy for travel, entertainment, gifts and other expenses that is five words long: ‘Act in Netflix’s best interest.’

In 1999, David Marquet was faced with a problem. He was expected to be in charge, and to instruct his team what to do, but he hadn’t been around long enough to know everything and didn’t have time to learn. What’s worse is that his team were widely regarded as the most poorly performing team. He took an unusual step and did the opposite of the expectations. He vowed never to give another order and turned to his team to decide what to do.

What’s even more surprising is that Captain David Marquet was the commander of the USS Santa Fe at the time – a US Navy nuclear submarine. For a captain to ask his crew what to do instead of telling them was unheard of. Captain Marquet was creating a system he called Intent Based Leadership, and he describes it in his book Turn The Ship Around.159 His crew came to him saying things such as ‘I intend to take the ship down 400m’ and he replied ‘Very well.’ His crew knew their mission and were empowered to make decisions about how best to deliver it. They knew the controls of the ship better than the captain and they made better, faster decisions when they were allowed to. On the Santa Fe, there wasn’t just one brain deciding what to do, there were 134. The ship’s performance improved, and within a couple of years their performance rating was the highest level ever assessed.

David Marquet had come to a similar conclusion as W. Edwards Deming did with his 95/5 rule – 95 per cent of the variation in a system is caused by the system itself, only 5 per cent is caused by the people.160 By changing how the crew were led, the worst performing crew in the fleet became the best.

Sadly, it isn’t as simple as just handing over control to the team. Not every team needs the same level of empowerment and autonomy; sometimes, too little direction and control can lead to teams freezing – unable to make progress because they don’t have the confidence or the knowledge to do so.

ONE SIZE DOESN’T FIT ALL

I was leading an organisation with around 100 software engineers in Agile teams, and had fostered a culture of high autonomy and empowered teams. Not all of the teams seemed happy, and neither were all of our customers.

I conducted a survey asking the teams a number of questions, including one about autonomy. I asked if they had enough, too much or too little autonomy. The results surprised me. Only around 50 per cent said they liked the amount of autonomy they had. Of the rest, about half wanted more and half wanted less.

Trying to take all teams to the same level of empowerment had not worked. Some needed to take smaller steps; they needed more direction and less freedom, at least for the moment.

Ladder of leadership

Marquet describes this problem with his ladder of leadership.161 This is a staged approach with seven rungs to the ladder – intent-based leadership is rung 5. Teams cannot jump up too many rungs at once, so a team or person on rung 1 or 2 may take some time and several intermediate hops before being able to reach intent-based leadership.

- At level 1 people ask to be told what to do.

- At level 2 they can explain what they see that might affect what the right decision is.

- At level 3 they say what they think should be done.

- At level 4 there is more confidence and they say what they would like to do.

- At level 5 they explain what they intend to do.

- At level 6 they describe the decision or action they have done.

- At level 7 the timeframe has increased and they say what they have been doing.

Agile leaders start with the assumption that people are trying to do good work and that, in most cases, poor performance is likely to be the fault of the system rather than the person. They assume trust and find ways to show that trust by delegating decision making downwards and asking teams to solve problems rather than perform tasks. They find ways to remove or mitigate processes and behaviours that remove decision making from the team.

Their role is to ensure that the work being done by the team is valuable to their stakeholders and that the team is competent and willing to complete it. Crucially, as we have already said, they must ensure the team knows the purpose of their work and are clear on the intent they are working towards.

Self-organising teams

Principle 11 of the Agile manifesto states that the best architectures, requirements and designs emerge from self-organising teams. It is rare for the most valuable work to always require the exact same mix of skills, so Agile teams adapt their composition, focus and skills to fit the work. In practice this means the specific tasks people carry out will vary and might not always be their preferred role. However, it can be tempting to pick lower priority work that you enjoy rather than more valuable but less enjoyable work. This delays value getting to the customer and risks starting work that never becomes a priority.

The best way to create a self-organising team is to hire a team that can adapt, change and learn. Hiring for fixed roles and specific skillsets might seem sensible when you understand their first project, but it doesn’t help when the skills need to change. Instead, ‘T-shaped professionals’ have one or more main skills but are also able to do other roles, perhaps at a lower skill level. This means they are much more flexible, and it is much more likely that across the whole team, they will have all the skills necessary to deliver the highest value work.

The second critical attribute for self-organising teams is to be able to learn new skills. Particularly in fast changing technical roles, skills don’t stay current for long and there are always new technologies, frameworks, systems and approaches to learn. Practices such as pair programming, buddying, mentoring and internal TED-style talks can help team members to learn from one another, but leaders must also invest time for more formal or directed learning. Once again, hiring people with a passion for learning and staying up to date is a good start.

People with a passion to learn and experiment can’t always find the opportunities to do so in their team. So why not find another way?

Since 2005, software company Atlassian have been hosting quarterly events for their employees where they have 24 hours to work on anything they want. They self-organise into teams, get creative and spend the day (and night) working together on something they can deliver. Originally called ‘FedEx days’ (because they had to deliver in 24 hours), they are now called ‘ShipIt days’162 and are a core part of their culture. They foster creativity and innovation and are a safe place to try new technologies.

Agile leaders expect change and expect their teams to respond to that change. They hire and form teams based as much on aptitude and potential future skills as for current ability. They create opportunities for people to grow and build team environments where moving around to create a better skills mix or a development opportunity is welcomed. Their teams are optimised for the work being done today and aren’t afraid to rebalance, reset and evolve to match the shape needed for tomorrow’s work.

This doesn’t always mean teams must be stable. While long-lived teams can be high performing, it is also possible to create high-performing teams that are short-lived or change frequently – in fact, dynamic reteaming is a core attribute of the Agile approach FAST (see Chapter 11). In our experience, the stability of team membership is far less significant in creating a high-performing team than the other factors we describe in this chapter. The benefits of being able to flex a team to optimise it for the changing needs of its members and the business far outweigh the risk that they take a little time to get themselves up to speed.

Creating strategic alignment

We know from Dan Pink’s work that high levels of autonomy are a powerful contributor to intrinsic motivation in knowledge workers (see Intrinsic motivation in this chapter). For startups and small, independent teams this can be straightforward to create, but it presents a problem in larger organisations, particularly those with more traditional structures and management approaches.

If the team is deciding what they do, how do you know they are doing the right thing? If you are lucky, the team might be connected to the high-level vision and be well enough informed that all their actions will be completely aligned with it. However, that isn’t always the case, so it is the role of a good leader to provide that alignment.

This combination of alignment and autonomy is not as contradictory as you may think. Alignment is not the opposite of autonomy; instead, it is better to think of them as two axes that we can move along in either direction. This concept was introduced in Stephen Bungay’s The Art of Action,163 where he used his military historian background to explain leadership theory. In a military context, the generals simply cannot micromanage the war fighters on the ground. Instead, they set clear direction for the soldiers (the what and the why) and trust their training and competence with high levels of autonomy in how they achieve the objective.

The music streaming company Spotify is famous for their approach to Agile, with their unique language and innovative style to applying an Agile methodology to their development. In 2014, one of their coaches, Henrik Kniberg, used quirky diagrams in presentations to explain their method.164 Part of their approach is a version of Bungay’s alignment and autonomy graph. The original described alignment (the intent; the what and the why) and autonomy (the how) as two axes and shows that when both are high, we achieve the best results. Kniberg’s Spotify model is described in his YouTube video,165 making it more relatable. Our version, based on the loyalty card case study, is shown in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2 Balancing alignment and autonomy

Balancing alignment and autonomy

The role of the leader is to provide sufficient alignment and strategic direction for the team, while also providing sufficient autonomy for them to make their own decisions and set their own direction. Too much alignment without autonomy requires the leader to have lots of detailed information and leads to feelings of micromanagement in the team. Too little alignment with high autonomy and the team can do what they want, but don’t really understand why they are doing the work. They risk building the wrong thing. Too little alignment and too little autonomy and the team doesn’t feel empowered to work out what to do and isn’t given instruction. This leads to confusion, inaction or irrelevant work being done.

Get both elements right, however, and the team is clear on its purpose (one of Dan Pink’s drivers of motivation) and clear on what they can do to achieve it. There is just enough control for the leader to be confident that the team is working on the most valuable work, and just enough direction that the team has control and autonomy over what they are doing and how they are doing it.

But it isn’t as simple as that. Alignment isn’t just with the high-level strategic goal, or the highest priority user needs. It also applies to technical decisions, style, branding, security, compliance, people processes and many other aspects. Each of these dimensions may require different levels of alignment and autonomy. The leader’s role is to get the balance right for all of them.

Three levels of autonomy

Table 9.4 breaks autonomy down into three distinct levels.

Table 9.4 Three levels of autonomy

Level 1 | pure autonomy |

Level 2 | constrained autonomy |

Level 3 | no autonomy |

The first level of autonomy, pure autonomy, is where the team has complete control over what they do. Examples of this may be how they implement an algorithm, what font they choose for their report or what their definitions of done are. For some teams, this could extend to all their work, but for other teams this isn’t true.

At the other end of the scale is no autonomy, where the team has no choice. For example, there may be a corporate design system that defines what colours and fonts to use on the website; a particular logging or auditing standard may be required for security reasons; or perhaps certain products or technologies must be used. Large organisations usually have fixed people processes, such as leave policy, sickness absence reporting, and so on; most teams will have some elements in this category.

In between pure autonomy and no autonomy lies constrained autonomy. This is where the team is still responsible for their decisions, but they must consult with a wider set of stakeholders to be confident that they are making the right decisions. They aren’t asking for permission or conceding the decision elsewhere, but there are factors outside their immediate team that may affect their decision and it is imperative that they know this. For example, their system may include a payment component; while they could implement this themselves, it’s possible that other teams may have already implemented something they can reuse, or have experience the team could benefit from. Or perhaps other teams may reuse something that this team is creating for the first time, so perhaps that may make the team implement it differently.

The role of an Agile leader is to create an environment where these connections and conversations happen. One where the team has the humility to ask for help and has a network of people who can provide that help.

It is important that the team still makes the decision. Managers (especially those with a Theory X background) tend to want to control more. This can move decisions away from the team. Perhaps the manager doesn’t trust that the team will do the necessary consultation, or will make the decision for the team, turning it into a constraint, not a choice.

Another risk is that constraints aren’t challenged, meaning opportunities to improve, update or replace them are lost. In the payment system example, perhaps there have been advances in technology that means our team should build a new solution rather than reuse an existing one. This should be the team’s choice, but one that is made in consultation with other teams and other stakeholders.

CREATING HIGH-PERFORMING TEAMS

The six key outcomes we have just described are all independently valuable, but deliver best results when implemented together. However, like much in Agile, they don’t come for free and just hoping they will happen won’t be enough. The Agile leader must actively create the environment for these six outcomes to establish, flourish and be sustained.

This is usually easier with small teams and becomes harder as the number of people and teams grow. As we seek to lead more people, the tendency to move towards Theory X management – adding processes, tools and even additional managers – can be strong. It is easy to justify each small, individual change, but, when they begin to add together, the impact on the culture and environment can be catastrophic.

A public sector organisation was struggling to respond to the pace of change their customers expected. They had established teams that were using Agile practices but were still in a more Waterfall mindset. To solve this, they opened a new office, hired for culture fit and an Agile mindset, and started applying Agile approaches from the outset.

This worked well, and grew to well over 100 developers. They kept a relatively flat hierarchy and adopted many of the qualities we describe in this book: they were transparent, balanced autonomy with alignment, focused on development and continuous improvement and had highly engaged and motivated people.

Three years later, however, they looked and felt very different. There were still roughly the same number of people, but now had more management, oversight and non-delivery focused roles, mainly resourced from jobs that used to be developers. Teams that had felt part of a wider, bigger development were now focused on developing just one component. Divestment went up, engagement and motivation went down, and they are now almost indistinguishable from their parent organisation’s teams.

Each small change, such as establishing a test lead, adding a more senior manager (to show how important the area was) or creating roles for outreach and innovation, made sense in isolation – and each of these changes was a well-intentioned attempt to make the organisation better – but each change also diluted one or more of the six leadership outcomes. They changed the opportunities for teams to have impact on the wider organisation and changed the emotional contract each person had with the organisation. Each change moved the organisation more towards the right of the Agile Manifesto and further from the ideals of the Corporate Rebels.

Creating and maintaining high-performing teams is a tricky balancing act for an Agile leader. Not only must you seek to maximise the six outcomes we have described, but, once there, you must also stop them being eroded. It is a bit like plate spinning in that it requires initial effort to get going but without a little involvement now and then to maintain momentum, the plates come crashing to the ground.

DON’T ASK WHY, ASK WHY NOT?

Agile teams are self-organising and have the skills, resources, authority and ability to deliver products of value to the end customer.

As teams and organisations grow, it can be common to see elements of that delivery taken out of the team and moved elsewhere – to another team or perhaps a newly created manager role. Rather than seek to provide justification as to why that is a good thing, concentrate on identifying the reasons why it might not be a good idea. What are the negative consequences to the change? Very often, the negatives quickly outweigh the positive reasons.

Teams contain individuals

To achieve high-performing teams also requires balancing the needs of the team with the needs of the individuals in the team. Great teams manage to align those two needs, but it can take some effort and it is easy to undo.

We have all probably experienced that state where we get so engrossed in our work that time seems to stand still, we forget about eating and drinking and, when we eventually look up, hours have passed. This is when we do some of our best work, and why multi-tasking and being constantly interrupted is so damaging.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes this state as ‘flow’166 – when skill and challenge are balanced. This presents leaders with a challenge themselves:

Surely, we want team members to be doing tasks we know they are good at, and we know they will successfully complete. But that work may not help them get into flow.

If they need new, challenging work to get into flow, how do I know they can do it? Doesn’t that add too much risk?

Of course, it’s not always that bad. Sometimes, part of the challenge can be work that is new, interesting or high purpose, even when it is something you have done lots of times before and are certain to do well. However, in time, carrying out homogenous work will increase your skill level to the point where you cease to find it challenging. You risk slipping into boredom and apathy, when, ironically, the quality of your work will often suffer.

High-performing teams adjust the work so that each team member is challenged, interested and productive. They need sufficient autonomy and complex and interesting enough work to be able to do this. This is easier when they start with larger, more complex work that they can break down in different ways to achieve the right mix of complexity.

Sometimes, the best thing may be to adjust the team membership. Some people believe that only stable, long-lived teams can be high performing. This isn’t true. Some very poorly performing teams are stable and long-lived, and some high-performing teams have constant movement of membership. What is important is that the change in team membership comes from the team; when they initiate the change, they will welcome and assimilate the new people quickly. Frequently welcoming new people also makes teams used to sharing their approaches and information and reduces silos of knowledge and single points of failure.

These approaches allow professional and personal development to be advanced along with product delivery, but it does require the encouragement and trust of leaders. Agile leaders understand the importance of high-performing teams and the actions that create, maintain and damage them.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CULTURE

The story of the software team that changed with new management initiatives in the previous section is an example of how the culture of an organisation can quickly change even though most of the people don’t; David Marquet’s story of the Santa Fe is another. But one of the most powerful stories of culture change being a product of the system, not the people, comes from motor manufacturing. It is an appropriate setting, given how the production line innovation of Henry Ford shaped much of today’s thinking of management, and the Toyota Way brought us Lean process improvement and influenced many of the Agile practices we have discussed. It is a story involving Toyota and their partnership with General Motors (GM) in the United States – New United Motor Manufacturing Inc (NUMMI).

In 1982 GM closed their manufacturing plant in Fremont, California. It was one of their poorest performing factories. There were over 6000 grievances on the books, drugs and alcohol were rife, absenteeism was over 20 per cent and it was regarded as the worst plant in the company. Two years later, NUMMI – a joint venture between GM and Toyota – reopened the plant and within one year absenteeism dropped to 2 per cent and the plant was rated as GM’s best. The most surprising thing was that this was done with the same people who worked at the previous plant – including the ‘troublemakers’ – and with the same unions and union leaders. They even had a ‘no lay-offs’ policy.

What Toyota had managed to do was completely change the culture of the plant without needing to change the people. As John Shook described in MIT Sloan Management Review,167 they didn’t seek to change how people felt or thought – instead, they focused on changing how people behaved. It was influencing what people did that made the most significant impact on how they felt and thought. The different behaviours led to the different culture.

Some of these behaviour changes were simple: managers and staff were more equal; there were no separate canteens or reserved parking spaces; there was a flat pay structure. Some changes were more extreme: if there was a problem, any worker could pull the ‘Andon Cord’, which would stop the line, causing everyone to come over to help solve the problem. When things go wrong, the Toyota Way is not to attribute blame – instead, problems are treated as an opportunity to make improvements.

Establishing and maintaining a new culture is difficult. The GM managers were frequently tempted to revert to old ways, to cut corners to keep the production line moving or to compromise on quality, but by staying true to the system – keeping their faith, recognising their mistakes and working with the workforce, not against them – the plant continued to thrive until it eventually shut in 2010. It is now owned by Tesla.

The culture of a team is critical to its success. While culture can come from the people, it is defined by how those people behave, not by who those people are. Agile leaders focus on the behaviours they want to see and assume that the people can adapt to those new behaviours. Conversely, no matter what you ask of your people, when their behaviours and actions do not change, neither will the culture. You cannot transform by continuing to do the same things as you used to do, even if you pretend you are by using new names or giving yourself a new job title.

LEADERSHIP IN AGILE TEAMS

We have spoken in this chapter about the importance of leadership for Agile teams, but where do we find it? The simple answer is that it should be everywhere. Agile teams are not hierarchical. Self-organising teams specifically don’t need a hierarchy, which means that anyone can take on a leadership role, but there are some roles that lend themselves more towards some elements of leadership than others, even with simple frameworks.

The Product Owner role is a natural role to provide leadership on alignment, strategy and purpose. The role is to ensure that the team is delivering the work of highest value, so requires them to know what that is.

The Scrum Guide explicitly states that the Scrum Master is a servant leader. So, the Scrum Master role is well placed to provide leadership on team practices, encouraging the team to self-organise, collaborate, learn from one another and so on. They can also initiate events that can grow psychological safety or create alignment, such as Agile chartering/Liftoff168 or the daily check-in protocol.169

There are also opportunities to lead for everyone in an Agile team, particularly in fostering psychological safety, and creating intrinsic motivation, self-organisation and trust. However, as we saw in the case study earlier, it is leaders (and managers) outside the team that can have the greatest impact – both positive and negative. Anyone that the team interacts with can be in a leadership role, including people who may not think they need to know anything about Agile. However, as we have shown in this chapter, Agile leadership is a critical enabler to the advantages of Agile and it is imperative that leaders – wherever they are – know this and are actively seeking ways to demonstrate Agile leadership.

Leadership roles in scaled approaches

We should mention other roles that exist in the various scaled Agile approaches, but do so with some hesitation. As we explore in Chapter 11, there are specific leadership roles defined in some Agile methods. It should be logical to assume that these roles would promote good Agile leadership; however, while that may be the intention of the method creators, in practice it isn’t always what we see. Instead, we often see these roles interpreted in ways that do not promote good Agile behaviours nor demonstrate good Agile leadership. We see a lot of Theory X management behaviours, a lot of decisions taken away from the teams, a lot of approvals, gates and delays, and a lot of people behaving in the same ways they did when they were in traditional, heavyweight programme delivery jobs.

Whatever role you are in, whatever job title you have and whatever other people are doing, we implore you to stick to the principles and values of Agile. This chapter and this book will help you to do that.

AGILE COACHING

One of the most effective ways to optimise your Agile leadership is to engage an Agile coach to help you. A good Agile coach will help to challenge, support and encourage you to become a better Agile leader.

Agile coaching is something you should expect to see at all levels within your organisation – working with individuals, teams and leaders. It isn’t a one-way role. Good Agile coaches have coaches themselves. We do, and so do our coaches. The principle of continuous learning means that we always have room to grow, develop and improve. Coaching can help us with that growth no matter how skilled we already are.

What exactly is an Agile coach?

Many people are familiar with executive or leadership coaches. An Agile coach is similar and can provide many of the same benefits; however, what sets an Agile coach apart is that they come with a bias towards Agile. This sounds obvious, but it means that an Agile coach will generally have more tools at their disposal to help their coachee. In addition to the skills of an executive coach, they are also experienced in a wide range of Agile practices and approaches.

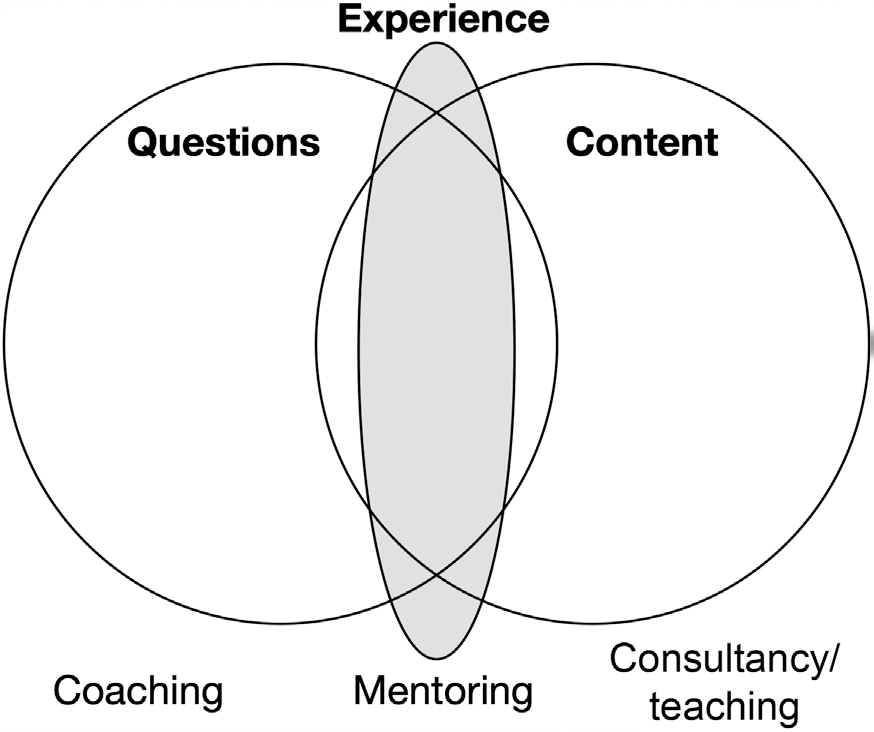

In an Agile coaching conversation, an Agile coach can move between three stances – coaching, mentoring and consultancy/teaching – as shown in the Agile coaching model in Figure 9.3.170

Figure 9.3 Agile coaching model

Sometimes an Agile coach uses powerful questions with their clients, but success depends on the client being able to reach the answer themselves. Sometimes, an Agile coach is teaching or consulting on a specific topic, where success depends on that specific topic being the right one for the client. By bringing broad Agile expertise and knowledge to the engagement, an Agile coach can help to bridge this gap with mentoring – combining powerful questions and active listening with information, experience, stories and advice that is tailored to the context of the situation. This helps the coach to accelerate the client’s growth towards an Agile mindset by adapting to their needs and having a broad toolkit of models, practices and ideas to draw upon.

Ideally, coaches will be mostly on the questions side, but sometimes the right thing is to provide content and answer questions, not ask them. Just as we adjust our leadership styles based on the maturity and preferences of the teams, we also adjust our coaching style.

Coaching teams

One-to-one coaching with an Agile coach is a powerful way to develop and advance Agile skill and competence. Agile coaches can also have a powerful impact on teams. As we discuss throughout this book, Agile is challenging to do well and it is easy for teams to lose focus. An Agile coach can help to identify this happening and coach the teams in how to bring themselves back on track.

Agile coaches can be full-time members of the team, or they can coach multiple teams. Each approach can work well. Coaches within the team can help to optimise practices and facilitate team events. Coaches outside the team can bring a detachment that could provide insights that the team miss as they are too close to the problem.

For more guidance on Agile coaching, see Lyssa Adkins’ fabulous book Coaching Agile Teams.171

Measuring value

By definition, any coach aims to help their subject, whether individual or team, reach their own conclusions and make their own decisions; the coach doesn’t tell them what to do. This can make measuring the value of coaching incredibly difficult.

The primary impact of Agile coaching ought to be more value for the customer, because the team optimises the work as it progresses so that a higher proportion of the work done is useful to the customer. This is hard to attribute to the coaching, since the decisions are made by the team, not the coach.

In 2005, internet giant Yahoo was adopting Scrum and Agile throughout the organisation. Gabrielle Benefield was one of the consultants helping them and describes the rollout in her paper, ‘Rolling out Agile in a Large Enterprise’.172 To begin with they got good feedback, with 64 per cent of teams reporting that using Scrum was making them deliver more business value; but as they scaled, they began to experience the kinds of challenges we describe in this book. Just encouraging teams to adopt Scrum didn’t seem to be enough for lasting improvement.

In response, they introduced a coaching model to help teams navigate these new ways of working and make the best of them. However, measuring the effectiveness of the coaching was harder to do. In the end, they settled on asking teams if they felt they were more productive. This is a subjective and non-ideal measure, but it did give them some powerful results. They found teams consistently reported productivity improvements at an average of 39 per cent. This self-reporting also led to an increase in coaching sessions as teams and their customers sought to maintain these levels of productivity.

The work mentioned above at Yahoo led to some statistics on the power of Agile coaching that are still realistic today:

- One Agile coach can coach around 10 teams a year.

- If each team is around 10 people, each coach has a reach of around 1:100.

- With a (conservative) 30 per cent improvement in productivity, each Agile coach creates the equivalent of an additional 30 team members per year.

That is an attractive return on investment.

A word on quality

As with many skills in Agile and IT, there is no quality threshold to call oneself an Agile coach. This means that people can (and do) market themselves as an Agile coach when they have little skill or experience in the craft. Sadly, poor coaches can do more harm than good by embedding poor practices, failing to identify systemic problems and focusing on the wrong things.

In an article by enterprise coach John McFadyen,173 he compares Agile coaches to sports coaches. Some are entry level, capable of doing a good job teaching teams the basics. Like a Sunday league coach, they mostly teach rather than coach, but do so with skill and passion.

The next level is intermediate; the public, minor leagues. Here we have player-coaches, those who are in a coaching role, but also on the team themselves, often the best player on the team. They know everyone’s role inside out, and can play well in most positions. They become a coach because they love helping others and are using the mix of practitioner and coach to hone their coaching craft.

At the final level, we have professional coaches. Their skill as a player isn’t enough to make them a good coach; they need new skills and the time and opportunity to hone them. They progressively improve and validate their skills and can help others be better practitioners than perhaps they could be themselves. This is the level of coach we need for larger transformations or complex Agile challenges.

Good Agile coaches recognise this transition and have invested in their coaching skill and craft. This may be though Agile certifications, such as those from Scrum Alliance or ICAgile, or could be from pure coaching training, but they will certainly be able to describe their journey, which is unlikely to be smooth. They will be able to tell stories of the problems they have faced, the mistakes they have learned from the people and books that have inspired them and where their journey is going now. If they can’t convince you of this, perhaps they aren’t the right person to help you on your path to being a great Agile leader.

SUMMARY

Most Agile teams do not exist in isolation, and they will not thrive if the leadership, management and governance around them is not also Agile. Yet, Agile leadership is not well described and often overlooked in Agile transformations in favour of applying Agile practices in delivery teams.

The default style for many managers and leaders is based on the industrial styles of management that were developed in the early 20th century. While these work well for predictable, repetitive work such as production lines, they are not well suited to the knowledge work that most organisations depend upon today. Instead, Agile leaders should seek to achieve for their teams the six leadership outcomes in Table 9.5.

Table 9.5 Six leadership outcomes for Agile leaders

Servant leadership | Leaders act with low ego. Their first objective is to serve their teams, not direct them. |

Psychological safety | Teams trust that they can speak out, challenge and be themselves at work without fearing the consequences. |

Intrinsic motivation | People motivate themselves when they have autonomy, can build mastery and have clear purpose. |

Empowered, trusted teams | The people closest to the information will make better, data-driven decisions when they are trusted to do so. |

Self-organising teams | Teams that have all the skills, experience and authority to deliver value for the end user. When those people are ‘T-shaped’ they can self-organise to ensure the most valuable work is always being done. |

Strategic alignment | Autonomy must be balanced with alignment. Agile leaders connect teams with the strategic purpose of their work at the right level to empower and not micromanage them. |

Each of these six outcomes will help teams work in an Agile way, but they are not simple or easy to achieve. They will feel alien, counter-intuitive and even wrong to many people used to traditional management. However, persevering will result in more empowered, engaged and motivated teams that make better decisions and deliver more value for their customers.

When trying to achieve and sustain these six outcomes, Agile coaches can be an invaluable support. Good Agile coaches support and empower teams and help leaders to identify challenges and blockers to their Agile journey.

141 Taylor, F. W. (1911) The Principles of Scientific Management. Dover Publications, Mineola, NY.

142 Fayol, H. (1949) General and Industrial Management (English trans. Constance Storrs). Pitman, London.

143 McGregor, D. (1960) The Human Side of Enterprise. McGraw-Hill, New York.

144 Drucker, P. (1967) The Effective Executive (reprinted 2007). Routledge, Abingdon, UK.

145 Bungay, S. (2011) The Art of Action: How Leaders Close the Gaps Between Plans, Actions and Results. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, Boston, MA, p. 62.

146 Marquet, D. (2020), Leadership is Language: The Hidden Power of What You Say and What You Don’t. Portfolio Penguin, New York.

147 Minnaar, J. and de Morree, P. (2020) Corporate Rebels: Make Work More Fun. Corporate Rebels, The Netherlands. https://corporate-rebels.com.

148 https://corporate-rebels.com/trends/.

149 Harbott, K. (2021) The 6 Enablers of Business Agility: How to Thrive in an Uncertain World. Berret-Koehler Publishers Inc, Oakland, CA.

150 Greenleaf, R. K. (1970) The Servant as Leader (reprinted 2008). Robert E. Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership, South Orange, NJ.

151 Hesse, H. (1932) The Journey to the East (reprinted 2021). General Press, New Delhi.

152 https://rework.withgoogle.com/print/guides/

5721312655835136/.

153 Duhigg, C. (2016) What Google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. The New York Times magazine, 28 February. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html.

154 Edmundson, A. (2018) The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

155 Reed, A. (2021) Change initiatives blog post, 15 June. CMC Partnership Consultancy Ltd. https://consultcmc.com/the-art-of-the-

tactful-challenge/.

156 Rock, D. (2008) SCARF: A brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others. NeuroLeadership J., 1, 1–9.

157 Pink, D. H. (2011) Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Canongate Books Ltd, Edinburgh.

158 https://jobs.netflix.com/culture.

159 Marquet, D. (2015) Turn the Ship Around! A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders. Penguin, New York.

160 The Deming statement is from his Introduction in Scholtes, P. R. (1988) The Team Handbook: How to Use Teams to Improve Quality. Joiner Associates, Madison, WI.

161 https://intentbasedleadership.com/.

162 https://www.atlassian.com/company/shipit.

163 Bungay, S. (2011) The Art of Action: How Leaders Close the Gaps Between Plans, Actions and Results. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, Boston, MA.

164 https://engineering.atspotify.com/2014/03/27/

spotify-engineering-culture-part-1/.

165 Kniberg, H. (2015) Alignment autonomy clip. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_qIh2sYXcQc.

166 Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2011) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Collins, New York.

167 Shook, J. (2010) How to change a culture: Lessons from NUMMI. MIT Sloan Man. Rev., Winter. https://www.lean.org/Search/Documents/35.pdf.

168 Larsen, D. and Nies, A. (2016) Liftoff: Start and Sustain Successful Agile Teams (2nd edn). Pragmatic Bookshelf, Dallas, TX.

169 https://thecoreprotocols.org/protocols/checkin.html.

170 Coaching model developed from an idea from John McFadyen.

171 Adkins, L. (2010) Coaching Agile Teams: A Companion for Scrum Masters, Agile Coaches and Project Managers in Transition. Addison-Wesley, Boston, MA.

172 Benefield, G. (2008) Rolling out Agile in a large enterprise. http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/447037/

6486321/1270929190703/YahooAgileRollout.pdf.

173 McFadyen, J. (2020) Agile coaching capability. Agile Centre. https://www.agilecentre.com/resources/article/

agile-coaching-capability/.