Ana Paula Ferreira, Marta Lopes

2A case of certified units in a Portuguese university: Interactions of ISO 9000 norms with HRM

practices, employee performance and employee satisfaction

Abstract: This study aims to assess organizational changes arising from the certification process according to the ISO 9001: 2008 norm, as well as assess the changes in human resource management (HRM) practices and in employee performance and satisfaction. From a population of employees in 3 certified service units of a Portuguese university, 248 valid questionnaires were used to support this research. Results are in line with previous research regarding general changes to the implementation and certification of ISO 9000: (1) internal restructuring – related to units’ management and functioning, as well as with the employees’ awareness of the quality of the services provided; (2) external restructuring – linked to the promotion of units’ image/reputation and customers’ satisfaction. Regarding HRM practices, some changes were identified in the planning of work, job analysis and description, and training and development practices. Some consequences in employees’ work were also perceived by the respondents: data show a perception of increased individual efficiency and efficacy in employees’ job performance, greater quality in orientation and control, increased levels of motivation and accountability, and increased workload. Summing up, data show changes derived from the implementation of the certification process: (1) changes in the execution and organization of work and in internal organizational procedures, (2) concerns of individuals and the organization regarding the quality of the service provided, (3) concerns with a unit’s external image/reputation, and (4) increased bureaucracy. Specifically regarding employee satisfaction, this certification process did not seem to negatively affect its levels.

2.1Introduction

Quality, certification, and its implementation through specific tools and techniques are embedded in political and economic agents’ discourse, and it is also a concern of managers, employees, and consumers. It started playing an important role in companies’ management after it was identified as a vital factor in policies and changes in organizations, enabling them to be more efficient and, as a result, more competitive in a global marketplace [1, 2]. Specifically, managing using a total quality management (TQM) approach seems to improve efficiency and product and service quality, reduce costs, increase customer satisfaction, and improve company performance (e.g., [2, 3]).

The ISO 9001: 2008 norm, as an approach to helping organizations manage through quality principles, establishes requirements for the creation of a quality management system (QMS) that effectively addresses customers’ demands through standards concerning continuous improvement, guaranteeing conformity of products or services with client demands and according to existing regulations. This management system aims to run and control an organization through quality issues. Quality, here, should be understood as the degree to which a set of inherent characteristics fulfills requirements [4]. Obtaining certification for a QMS implemented according to the ISO 9001: 2008 norm means that a third party gives a written guarantee that a product, process, or service is in conformity with specified requirements [5].

Nowadays, a growing number of companies are looking to obtain ISO 9001 certification of their QMS to assure the quality of their products or services. In fact, and according to data from the 2014 ISO Survey of Management System Standard Certifications, 1,138,155 companies, dispersed throughout 188 countries, are ISO 9001 certified [6]. Sampaio and Saraiva [7] show that in Portugal, as in the rest of the world, QMS implementation in accordance with the ISO 9001 norm is by far the most important certification for companies. The same ISO Survey shows that 8006 Portuguese companies are certified according to this norm [6].

Thus, it seems that providing products or services of high quality and, as a result, being able to satisfy customer needs is a central task of all companies.

Although existing research relating QMS implementation to the role of human resourcemanagement (HRM) practices is scarce, the existing evidence seems to point to an important link between these practices (e.g., [1–3]). Also, the numbers displayed by the ISO surveys show the importance of the QMS implemented according to the ISO 9000 and 9001 norms. As a result, studies linking this particular set of quality certification processes and HRM seem to be important in helping organizations to improve the process and the expected results of its implementation.

Because those studies seem to indicate that the relationship between these dimensions has a positive effect on organizations, the present study aims to contribute to enhancing knowledge on the subject. Specifically, it aims to assess organizational changes that arose from the implementation of a quality certification process using ISO 9001, as well as the interactions with HRM practices and with employees’ performance and satisfaction. The target population was the already certified service units – the academic service unit, the social service unit, and the documentation service unit – of a Portuguese university, the University of Minho (UM). The data used here came from a broader case study on the perceptions of managers and employees regarding QMS implementation [8].

This chapter starts by defining the dominant concepts at hand: quality and QMSs, the context of ISO 9000 and 9001 norms, HRM practices, and the relationship between QMS and HRM. Then the methodology used for the study is presented, along with a discussion of the results. Finally, some recommendations are offered.

2.2Quality in the management of organizations

The common use of quality as a synonym for attribute or characteristic does not make its definition any easier. Even recognizing when it is lacking, quality is still subjective, complex, multifaceted, and difficult to accurately measure. Top authors define quality quite differently: Juran [9] states that quality means “fitness for use” because products and services must incorporate customers’ viewpoints; Crosby [10] asserts that it is conformity to requirements; Deming [11] defines quality as anything that improves the product in customers’ eyes, and Tribus [12] says it is what makes customers feel passion for a product or service.

In a management context, quality is considered a philosophy and culture that puts clients at the core of an organization’s activity, conveying the message that the entire organization exists to satisfy the client. In fact, quality as a new management paradigm is present in the work of Philip B. Crosby (1926–2001), William E. Deming (1900–1993), and Joseph M. Juran (1904–2008), and they treat quality as a useful and differentiated management tool. Quality can also be seen as a process to be built around a group of norms that provide a set of principles, steps, and recommendations to help managers ensure organizations’ success. This perspective evolves from quality control tools into quality management and, ultimately, TQM (e.g., [13, 14]).

The norms under ISO 9000 were compiled by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) with the collaboration of a group of worldwide experts. These norms are at the core of the QMS implementation and certification of companies all over the world. Their main purposes are to ensure customer satisfaction and continuous improvement of organizations through quality management.

The quality concept also leads to the development of models of excellence. The Malcolm Baldrige1 (USA, late 1980s) and the European model of EFQM2 (early 1990s) were conceived by a small number of senior CEOs and focused on top management teams to achieve corporate excellence as a way to sustainable success.

The widespread application of ISO 9000 and the movement of business excellence, owing to the American and European quality awards, are some of the dominant approaches to managing through quality principles [16].

Thus, and despite the importance and recognition obtained by each of the “groups” of the presented models, the dimension of the ISO 9000 phenomenon, achieved largely through the ISO 9001 norm, gives relevance to this study. As a result, this research will adopt the definition of quality according to the ISO 9000: 2005 norm: the degree of satisfaction of requirements given by a set of intrinsic characteristics.

ISO 9000 norms

Founded in 1947, the International Organization for Standardization is an “independent, non-governmental international organization with a membership of 161 national standards bodies. Through its members, it brings together experts to share knowledge and develop voluntary, consensus-based, market relevant International Standards that support innovation and provide solutions to global challenges” (http://www.iso.org/iso/home/about.htm, retrieved 23 May 2016).

The ISO 9000 norms were born in 1987 as an expression of international consensus on good management practices (http://www.iso.org/iso/home/about/the_iso_story.htm#12, retrieved 22 June 2016). Since then, those norms have undergone three reviews (1994, 2000, 2008) to incorporate the theories of quality that have emerged. In this series, those that relate to QMSs are as follows3:

–NP EN ISO 9000: 2005 – covers the basic concepts and language

–NP EN ISO 9001: 2008 – sets out the requirements of a QMS

–NP EN ISO 9004: 2011 – focuses on how to make a QMS more efficient and effective

These general norms of universal application “are undoubtedly the best known ISO publications and have been widely accepted as the basis for organizations to gain confidence of their customers and other interested parties, on their ability to understand customer requirements, legal requirements and regulations, and to systematically provide products and services that meet those requirements” [17, p. 16].

Certification is not an ISO requirement; however, ISO 9001 is designed to enable an organization to demonstrate compliance with it, using an independent third party, a certification body, with the intention of enhancing the confidence of current and future customers that it has the ability to consistently provide conforming products [18]. Thus, associated with the 9000 series there is also ISO 19011: 2011, which depicts the guidelines for auditing management systems.

The ISO 9001: 2008 norm is the benchmark for the implementation of a QMS in organizations. The QMS requirements specified in this international standard complement requirements for products and can be used by internal and external parties, including certification bodies, to assess an organization’s ability to meet customer demands and statutory and regulatory requirements that are applicable to the product and in line with the organization’s own requirements [19].

Eight quality management principles described in ISO 9000: 2005 underlie the development of ISO 9001: 2008; they may be summarized as follows [4, 17]:

–Customer focus: organizations must understand the needs of customers (current and future), satisfy their requirements, and seek to exceed their expectations;

–Leadership: leaders must create and maintain an internal environment that allows people’s full involvement in achieving organizational goals;

–Engaging people: as the essence of an organization, organizational members should be fully involved; this enables the use of skills for the benefit of the organization;

–Process approach: managing activities and resources as a process allows organizations to obtain the desired results more efficiently;

–Managing with a system approach: to identify, understand, and manage interrelated processes as a system contributes to achieve organizations’ goals more efficiently and effectively;

–Continuous improvement: continual improvement of overall performance should be a permanent aim of an organization;

–Approach to decision making is evidence-based: effective decisions are the result of data analysis and information;

–Mutually beneficial relationships with suppliers: a relationship of mutual benefit between the organization and its suppliers enhances the ability of both parties to create value.

The ISO 9001: 2008 norm also proposes a specific model of a QMS process based and centered on a Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) methodology: plan, to establish the goals and necessary processes to deliver results in accordance with customer requirements and the organization’s policies; do, to implement those processes; check, to monitor and measure processes and products, comparing them to the policies, objectives, and requirements for the product, and to report the outcomes; act, to continually improve the performance of processes [19].

Generically, the purpose of an audit of an implemented QMS according to ISO 9001: 2008 is to assess whether an organization has identified, and is managing, its processes using the PDCA methodology in order to obtain the desired results, which means “conforming products” [17].

Quality and Human Resource Management

It is commonly accepted that human resources (HR) are one of the main assets of organizations and one of the factors that determine their progress [20]. HRM includes all activities that organizations dedicate to attract and retain employees and to ensure they have the highest possible performance to contribute to the achievement of an organizational purpose. These activities constitute the organization’s HRM system, which is designed so that it is internally consistent, consistent with the other elements of the organizational architecture, and consistent with the strategy and objectives of the organization in order to improve efficiency, quality, innovation, and the response time to customer inquiries or complaints – the four basic elements of competitive advantage, according to Jones and George [21].

The importance given to the different practices of HRM, as key elements within quality management models and paradigms, has been quite remarkable since the beginning of the quality movement. Pioneering authors in this area emphasized some of these practices in their work. For example, Juran [9] postulated the importance of training, the creation of teams, and recognition in their methodology for improving quality; Crosby [10] made reference to the need for teamwork to improve quality; and Deming [22], who in his 14-point list, explicitly mentioned the implementation of job training, education and self-improvement programs, and employee involvement. All theoretical proposals in defining the concept of quality management that emerged later also included items directly related to HRM such as teamwork, education, training, and employee involvement [23].

Still, Vouzas [16] points out that the relationship between HRM and quality was widely underestimated. Only recently have quality experts, researchers, academics, and other professionals realized and clearly assumed that issues related to HR are at the heart of a quality philosophy and that their involvement and commitment are essential for the successful implementation of any initiatives, practices, and techniques aimed at improving quality. Additionally, it was also recognized that quality management has important implications for managing and organizing work and, in parallel, for HRM.

The ISO 9001: 2008 norm underlines, as mentioned in clause 6, the importance of “resource management.” In subclause 6.1 it is stated that the provision of resources should be determined and provided by the organization. In turn, subclause 6.2, related specifically to HR, emphasizes both the key role of workers in the conformity of product requirements and the need for them to have the opportunity to have education, training, know-how, and appropriate experience. It is also the responsibility of organizations to ensure the competence, training, and awareness of its HR. In addition, subclause 5.5 (“responsibility, authority and communication”) underlines the leading role of top management in defining and stating responsibilities, communicating results, and promoting awareness of QMS in the entire organization.

The aforementioned requirements demonstrate the relevance that ISO 9001 attaches to planning, skills, training, participation, and communication. At the same time, among the basic principles of this norm, the key role of people in an organization’s performance is stressed, as is the relevance of their full involvement. For this reason, the importance of HR, according to Hassan [24], has often been highlighted in mission statements, policies, and quality strategy.

Nevertheless, several criticisms of the ISO 9000 movement have been addressed. In the first place, it has created an industry of millions, with a vast number of individuals and organizations depending on it for their subsistence: consultants, auditors, quality managers, companies, and training and certification agencies (and their workers) [25]. These criticisms also extend to the fact that it is a very expensive and generic process, with a heavy “red tape” component, a process that seems to be out of context in relation to HR, and is also heavily dependent on external auditors [25, 26]), especially in the first versions of the norm.

In fact, very little empirical knowledge is available on this subject. The literature linking HR issues with quality and certification issues is still quite limited, especially given a focus on the relationship between those subjects and the impact of the implementation of ISO 9001. Also, most of these studies are descriptive in nature, seeking to contribute only a better understanding of the role of HRM in improving quality. Furthermore, the relationship between HRM and ISO 9000 certification is often reduced to HRM commitment in the design and implementation of a QMS [1, 3, 16].

However, Bayo-Moriones and colleagues [23] point to empirical studies that have already established a positive relationship between an ISO 9001 certified QMS and HR training and development (T&D). Effectively, integrating the QMS with HRM seems to be increasingly recognized as an important success factor. According to Hassan [24], experts, researchers, and quality professionals argue that people are at the center of the quality philosophy, and they argue that unless the involvement and commitment of people is achieved, the success of any quality improvement program will be compromised.

Quazi and Jacobs [26] studied the nature and extension of the impact of ISO 9001 on T&D in firms in Singapore and found that ISO 9000 certification affected training needs, models, methods, and evaluation. Improvement was reported in dimensions like HR development, hours of training, and types of training.

Hassan et al. [27] developed a study aimed at measuring employees’ perceptions of HR development practices. The idea was to explore whether ISO certification led to improvements in HR development systems, examine the role of HR development practices on workers’ personal development, and assess quality orientation in organizations. Participants in the study included 239 workers belonging to 8 organizations (4 of them with ISO certification), who responded to a questionnaire assessing the following systems: career, job planning, development, self-renewal, and HR development. Results showed a higher average score of ISO-certified companies compared to non-ISO-certified ones. Regarding the issues related to ISO certification and to orientation toward quality, this study concluded that companies with ISO certification had significantly higher ratings concerning career systems, which included HR planning, recruitment, performance evaluation systems, and promotions, as well as the level of job planning and quality orientation. In the remaining variables, the mean differences were not significant, although so-called ISO companies always enjoyed some advantages over the non-ISO ones.

Rodríguez-Antón and Alonso-Almeida [28] conducted a study on QMS certification and its impact on job satisfaction in services with high customer interaction. According to the authors, many organizations have implemented a QMS to increase their competitiveness, which allowed them to systematize and improve internal processes, as well as see organizational and financial returns. However, the researchers noted that there was little evidence on the impact of ISO implementation and certification on job satisfaction. Although it seems obvious, few empirical studies have argued that the more satisfied workers are, the greater their commitment to the organization, the better they serve clients, or the more their behavior influences the results derived from quality management. Furthermore, the same researchers found some studies showing that more highly skilled workers offer better customer service, which contributes to customer satisfaction, and organizations with a QMS that leads to improvements in working conditions promote greater involvement of workers, increased motivation, and a feeling of safety at work.

So in order to assess these claims, Rodríguez-Antón and Alonso-Almeida [28] developed and administered a questionnaire of managers of 943 ISO 9000–certified Spanish hotels. Data showed that this sample did not corroborate the conclusions drawn in the earlier literature, perhaps because the workers were not directly accessed.

Prates and Caraschi [29] studied the organizational impact of ISO 9001 implementation and certification in Brazilian paperboard companies. From their literature review they also concluded that the HR area is one with greater participation in this process, especially regarding worker T&D, given that the HR area is responsible for developing, implementing, and managing policies and procedures of T&D to attract and maintain employees’ involvement regarding the organization’s QMS. Moreover, it is essential that workers realize that job descriptions, training plans, and the evaluation of training effectiveness are directly interconnected, and therefore skill development and an appropriate task distribution facilitate the production process, reduce failures and waste, and, hence, reduce costs. While administering a questionnaire to estimate the direct impact of ISO 9001 on HR performance – by assessing dimensions like changes in work responsibility resulting from ISO 9001 certification, the role of HR in a certified QMS, the value given to the norm’s principles and to customer requirements in HR T&D – these researchers discovered that ISO 9000 certification had a positive and significant impact on production, purchasing, and marketing, as well as on HR.

2.3Certified units of Minho University

The present research was carried out on the certified service units of UM. A brief description of those units and of the university follows.

Founded in 1973, UM is a (northern) Portuguese public institute of higher education, with two main campuses, 25 km from each other. The university’s teaching activities date back to 1975/1976. According to the information in the UM’s activity report from 2014, UM had 18,330 students enrolled in 220 degree courses, in addition to 55 students enrolled in specialized training courses and 22 in advanced stages of scientific/postdoctoralwork. Currently, the university’s mission is to “produce, disseminate and apply knowledge based on freedom of thought and plural critical judgments, promoting higher education and contributing to the construction of a society based on humanistic principles – with knowledge, creativity and innovation as growth factors, sustainable development, welfare, and solidarity” [30].

UM adopts an organizational matrix model that promotes interaction among its units, with the view to carrying out projects that fulfill its mission and efficiently use its resources. The main structures of the university are its 11 teaching and research units: School of Architecture, School of Sciences, School of Health Sciences, Law School, School of Economics and Management, Engineering School, School of Psychology, Nursing School, Institute of Social Sciences, Institute of Education, and Institute of Languages and Human Sciences.

Also, UM has specific research units, cultural units, differentiated units, service units, and support offices. The last two constitute the set of infrastructures and support services for students and teachers who seek to meet the various needs of students. Among the service units are the Academic Services (ASU), Social Services (SSU), and Documentation Services (DSU), the only UM units that currently have certification of its QMS based on NP EN ISO 9001: 2008.

Regarding human resources, again according to the 2014 activity report [31], UM has 1286 teachers and researchers and 602 non-teacher/researcher employees.

Academic Services Unit

According to the internal UM’s regulation regarding service units [32], the ASU’s purpose (mission) is the administrative management of students’ educational processes, while attending to the needs of students, teachers, and the general public.

In this context, the ASU comprises divisions and sectors with different activities, including the Initial Training Division, the Graduate Division, the Pedagogical Division, the Attendance and Quality Division, and the Secretarial Service, offering their own facilities on both campuses. The ASU has 39 employees in various positions and professional careers, as well as one trainee under the UM internship program.

The QMS implemented here (according to ISO 9001: 2008) was certified in July 2012 by the Portuguese Certification Association (APCER), and this specific unit provides pedagogical and administrative support services to the teaching projects of UM.

Social Services Unit

According to the organic regulation [31], the SSU has administrative and financial autonomy and comprises five departments: Office Administrator, Administrative and Financial Department, Food Department, Cultural and Sports Department, and Department of Social Support.

The SSU’s is charged with providing social support for students, including helping them with accommodations, meals, scholarships, medical and psychological support, and support for sports and cultural activities, among others. Regarding its staff, the SS employs 232 people.

In 2009 [33], this unit obtained a double certification from APCER, both for its QMS and for food safety based, respectively, on NP EN ISO 9001: 2008 and 22000: 2005. The certification of the QMS emphasizes that SSU provides services regarding meals in canteens and bars, accommodations, healthcare services, and sports and cultural activities. It is also responsible for the allocation of scholarships.

Documentation Services Unit

The DSU is, as stated in the organic regulation of the UM service units [31], an integrated system that encompasses all functional units of library and bibliographic information and all academic libraries of the university. This unit is responsible for collecting, managing, and providing, to all university sectors, scientific, technical, and cultural information necessary for accomplishing its duties and for participating in systems or networks of bibliographic, scientific, and technical information in accordance with the interests of the UM.

Relying on 39 employees to achieve its goals, the DSU is divided into the Library Division, the Information Division, and the Secretariat Section.

The DSU has implemented its QMS for the provision of documentation services, access to information, and infrastructure for research and study in Braga (the university’s general library and it Congregados library) and Guimarães (Guimarães Library). APCER certification happened in July 2009.

2.4Methods

As already mentioned, the present research aims to identify organizational changes resulting from the implementation and certification process, both in HRM and in employee performance and satisfaction.

Although there is no unanimous consensus on its validity, job satisfaction is one of the commonly used variables for understanding and assessing employee performance. Conceptually, Locke in 1976 (cited by [34]) defined job satisfaction as a positive emotional state or a state of pleasure resulting from the assessment of one’s work or work experience. Thus, job satisfaction is a feeling or emotional state resulting from working conditions that will influence individuals’ attitudes toward their employers. This influence can be exerted positively, benefiting organizations, or negatively, harming them.

Based on these definitions, it is not surprising that job satisfaction is constantly linked to performance, and people seem to take for granted that more satisfied workers are more productive, have better performance, and show lower turnover and absenteeism rates. However, this optimism is not always real – job satisfaction can result, for example, from a perception of easy, pleasant, or enjoyable work, combined with a generous salary; in fact, some empirical studies do not corroborate this assertion about a positive association between job satisfaction and performance [34–37].

Satisfaction at work results not only from individuals’ assessments of their work but also of their lives in general. Thus, it cannot be automatically assumed that this emotional response is a sine qua non condition that can be used to explain performance or commitment to work, or even commitment to an organization. In fact, Cunha and colleagues [36] emphasize motivation more than satisfaction as a variable that influences behaviors. However, it cannot be ignored that some studies continue to show satisfaction as a significant dimension to explain performance because it seems to clarify why people adopt behaviors that benefit organizations such as lower voluntary absenteeism and turnover.

Advocating this line of thought, Domingues [38] states that employee satisfaction contributes to organizational success since workers’ feelings influence their performance. As a result, developing and maintaining high organizational performance standards depends on employee satisfaction; hence, the importance of measuring satisfaction is increasingly recognized by quality management models.

To achieve the main purposes of this study, the following research questions were defined:

–What organizational and job changes result from a QMS implementation and certification?

–What are the interactions of QMS implementation and certification with HRM?

–What are the implications for employee satisfaction and QMS implementation and certification?

Procedures

A questionnaire was developed and administered to the employees of three UM service units to assess their perceptions regarding the consequences of QMS implementation and certification4.The questionnaire was comprised of three sections. Section I was devoted to the implementation and certification process of the QMS according to ISO 9001 and included 30 statements on which each respondent was to mark the degree of agreement on a 6-point Likert scale (with 1 denoting strongly disagree and 6 strongly agree). Section II addressed employees’ satisfaction with their job and with the certification process, with 15 statements on which each respondent again indicated the degree of their satisfaction on a 6-point Likert scale (with 1 indicating very dissatisfied and 6 indicating completely satisfied). Section III was concerned with personal and professional information. Data were collected using optical recognition software, and for data analysis IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 for Windows was used.

Sample

During June 2014, the questionnaires were distributed by an intermediary in each unit. Anonymity was assured, and the study’s purposes were explained to participants, and the interest of the units in the study’s results was also emphasized, given that the study would help them understand how to overcome a flaw in the certification process: the exclusion of workers’ perceptions regarding the certification process.

The actual sample refers to the units’ populations. Out of a total of 311 workers, 248 (79.7%) questionnaires were validated, where 31 (12.5%) were from the ASU, 183 (73.8%) from the SSU, and 34 (13.7%) came from the DSU.

Women made up 66.4%of the sample, and 82.1% of respondents had been working in their respective units for more than 7 years. Most of them (44.3%) had 9 years of schooling, or between 10 and 12 (32.9%), and as a result, the main professional careers were operational assistant5(56.9%) and technical assistant6(25.8%). In addition, 3.1% of study participants were managers and 11.1% were qualified staff.

The education and career dimensions were different among the three units. In the ASU, 55.2% were graduates and 58.6% were technical assistants; in the DSU, 65.6% of the participants had between 10 and 12 years of schooling, and 78.1% were technical assistants. The SSU was the unit with the lowest levels of education: 59.3% had less than 9 years of schooling, and 78 %were operational assistants.

Dividing the workers from each service into those who went through the implementation and certification process and those who did not, data show that only 3.2% of ASU workers, 9.6% of SSU employees, and 6.3 %of DSU workers did not experience that process.

2.5Results

In relation to the questions about changes brought by the implementation and certification process (Section I), higher scores were related to improvements in the unit’s external image, an increasing concern of the unit with customer satisfaction, increasing customer satisfaction with the unit, a more rigorous planning of work, and greater formalization of procedures. The average scores for these items were very close to 5 (agree), reflecting an actual agreement. Also, with values between 4 and 4.50, respondents showed that QMS implementation affected their own performance (e.g., “increased my orientation toward quality” or “improved my performance”).

Table 2.1: Implications of QMS implementation and certification.

Table 2.2: Implications of QMS implementation and certification: comparison between units.

At the opposite extreme, lower average scores were obtained in connection with statements related to resistance to change, task/work flexibility and simplification, and increased productivity. Table 2.1 presents the means and standard deviations regarding the implications of QMS implementation and certification.

Table 2.2 presents the means of the five highest and lowest scored statements of each unit regarding the implications of QMS implementation and certification. Comparing the five highest scores of each unit, it turns out that the most significant items did not fully coincide. It can be seen that the units only have in common an increased concern with customer satisfaction. The ASU and DSU have three more items in common, all related to internal procedures: the amendment, clarification, and greater formalization of procedures. The SDU still has in common with the SSU the improvement of the external image of the unit. In contrast, the two items with the lowest agreement means are common to all units.

Table 2.3: Employee satisfaction with work and with the certification process.

Data from Section II, regarding employee satisfaction with work and with the certification process, showed as higher scored statements the quality of service provided to customers, the unit’s customer focus, the unit’s QMS, working in the unit, and cooperation within the team. The lower scored items were working conditions, supervisor recognition of work performed, training provided, workload and work quality, and sharing of the unit’s objectives, goals, and results (Table 2.3).

Table 2.4 presents the means of the five highest and lowest scored statements of each unit regarding employee satisfaction with work and with the certification process. Comparing, once again, the five highest scores for each service, the four most significant items are the same among the units and have the same global mean score: satisfaction with the quality of service provided to customers, focus on the customer, the QMS of the unit, and working in the unit. Also, in line with the global scores, SSU workers showed a high level of satisfaction with “cooperation with the team.” ASU workers also expressed satisfaction with actions that were taken in the certification process to improve the quality of provided services, and DSU workers emphasized satisfaction with access to information needed to perform their jobs.

The two items with the lowest satisfaction scores matched among the units and the overall result. However, contrary to the global results, in the ASU and the DSU, those items are close to point 3 (“neither satisfied nor dissatisfied”); this seems to suggest a certain indifference regarding “supervisor’s recognition of the work performed” and “physical working conditions.”

Table 2.4: Employee satisfaction with work and with the certification process: comparison between unit services.

To reduce the number of variables, a principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation was performed. The dimensions found by this procedure with a minimum value of 0.60 in Cronbach’s alpha (internal consistency analysis) were accepted [38].

Table 2.5 shows the PCA results regarding employee perceptions about the implications of QMS implementation and certification (Section I). Data indicate six dimensions that explain 68.6% of the total variance: job execution and performance (C1): reflects changes in work conditions and in the way of carrying out one’s work as well as employee perceptions regarding their own performance; employee awareness (C2): depicts employee awareness of individual changes according to the new demands; Work procedures and organization (C3): reflects modifications in internal procedures and in the way work is organized; unit performance (C4): reveals the units’ concern with providing quality services; unit’s external image (C5): reflects changes regarding the external image of the units; and bureaucracy (C6): single item reflecting the increase in “red tape” procedures.

Table 2.5: PCA of implications of QMS implementation and certification.

Table 2.6: PCA of employee satisfaction with work and with the certification process.

Item 28 (“I had some resistance to the changes introduced”) was removed from the analysis due to a loading lower than 0.5.

Another PCA was performed concerning employee satisfaction with work and with the certification process (Section II). Results can be seen in Table 2.6, and the two extracted factors explained 62.3% of the total variance. Satisfaction with the units’ management and functioning (S1) translates the employees’ satisfaction with the changes arising from the certification process with the unit’s current organization, functioning, and management. The second dimension, satisfaction with working conditions (S2), reflects employee satisfaction with the work context.

Item 3 (physicalworking conditions) was removed from the analysis due to a loading lower than 0.5.

To explore the interaction between the study’s variables, correlations were then determined. The associations between the six dimensions regarding the implications of QMS implementation (C1 to C6) with demographic and professional variables of education and job tenure (years in the current unit) can be seen in Table 2.7.

Table 2.7: Correlations between implications of QMS and demographic and professional variables.

Notes: * Correlation significantat p < 0.05.** Correlationsignificantat p < 0.01.

Table 2.8:Correlations betweenimplicationsof QMS andemployeesatisfaction.

Notes: * Correlation significant at p < 0.05. ** Correlation significant at p < 0.01.

Table 2.7 shows that only education is associated with some of the implications regarding QMS implementation and certification, negatively with job execution and performance (C1) and employee awareness (C2), and positively with work procedures and organization (C3). Thus, as employees’ qualifications increase (decrease), perceptions of the implications of QMS implementation regarding job execution and performance and employee awareness decrease (increase). On the other hand, as employees’ qualifications increase (decrease), perceptions regarding the consequences of QMS implementation and certification in work procedures and organization increase (decrease). The same procedure was performed regarding employee satisfaction with work and the certification process and demographic and professional variables, but no associations were found. Table 2.8 shows the correlations between implications of QMS and employee satisfaction.

There are several positive correlations between these dimensions. In fact, satisfaction with the units’ management and functioning (S1) is associated with all dimensions regarding QMS implementation, with the exception of bureaucracy. That means that employee satisfaction regarding unit management and functioning increases (decreases) when perceptions of QMS implications also increase (decrease). The same reasoning is applied to the relationship between employee satisfaction and working conditions, and all the dimensions of QMS implications, with the exception of work procedures and organization (C3) and, again, bureaucracy (C6), where no association was observed.

Table 2.9: Average of QMS implications by Unit.

Table 2.10: Average of employee satisfaction by Unit.

| Unit | S1 with Unit | S2 with work cond |

| ASU | 4.01 | 3.99 |

| SSU | 4.27 | 4.35 |

| DSU | 4.15 | 4.27 |

| Global | 4.22 | 4.30 |

In an attempt to assess the possible existence of differences between each of the units regarding the dimensions of QMS implications and of employee satisfaction, it is important to compare the global average obtained by each of these dimensions to the average obtained for each unit separately.

Regarding QMS implications, Table 2.9 shows that AS presents a lower average of agreement in three of the six dimensions, namely, C1, C2, and C6. The SS has the highest averages in five dimensions, C1, C2, C4, C5, and C6, while the DS has the C3 factor with the highest average of agreement. All in all, the degree of agreement regarding the perception of the consequences of QMS revolve around point 4 (“partially agree”), a result that reflects significant agreement with these implications.

Regarding employee satisfaction dimensions, Table 2.10 highlights the ASU with a lower average of satisfaction in comparison to the other units. The SSU, on the other hand, has the highest average. Again, the differences do not seem significant.

Expanding these comparisons, a one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was performed using the Bonferroni post hoc test because of the small number of comparisons to be made and the observed frequency differences. The analysis was carried out to see the effects of the variables: Unit (ASU, SSU, DSU) and Professional Career (Unit Manager – UM; Senior Technician – ST; Technical Assistant – TA; Operational Assistant – OA; and Others – O) on the score obtained by the dimensions concerning QMS implications and on those concerning employee satisfaction. Table 2.11 shows the frequencies of each independent variable.

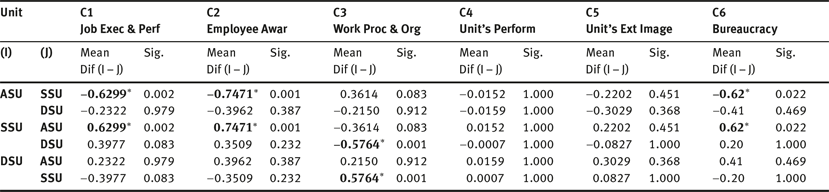

This statistical procedure made it possible to determine, with regard to the consequences of QMS, and as translated in Table 2.12, that for C1, C2, and C6 dimensions there are significant differences between the ASU and the SSU; SSU workers show greater agreement regarding the existence of these implications. In addition, regarding the C3 dimension there are significant differences between the SSU and the DSU, where the latter shows greater levels of agreement regarding the existence of consequences on work procedures and work organization. For the C4 and C5 factors no significant differences emerged.

Table 2.11: Frequencies of independent variables (units and professional career).

| Independent variable | Label | n |

| Unit | ASU | 29 |

| SSU | 161 | |

| DSU | 31 | |

| Professional Career | UM: unit manager | 7 |

| ST: senior technician | 24 | |

| TA: technical assistant | 56 | |

| AO: operational assistant | 127 | |

| O: other | 7 |

Results on employee satisfaction show no significant differences between S1 and S2 factors (Table 2.13). However, testing a dimension of overall satisfaction – S Global (all items of employee satisfaction were included: α = 0.948), a significant difference between the ASU and the SSU can be seen, where SSU employees reveal a greater overall satisfaction with QMS implementation and certification.

Examining what happens with professional careers (Table 2.14), we observe that there are only significant differences for the C1 and C3 dimensions. For C1 the difference is between senior technicians and operational assistants, where the latter express a higher level of agreement for QMS implications in job execution. With the C3 dimension, work procedures and organization, the difference is relevant between technical and operational assistants, where the former had a higher score on agreement.

Turning now to employee satisfaction with the QMS process, significant differences can be seen in S1 and S Global for the same careers (Table 2.15). Both satisfaction with unit management and functioning and global satisfaction are dimensions where unit managers produced significantly higher averages than the other careers (except “others”).

Table 2.12:Comparisons between QMS implications and units.

Note: * The mean difference is significant at 0.05.

Table 2.13:Comparisons between employee satisfaction and units.

Note: * The mean difference is significant at 0.05.

Table 2.14:Comparisons between QMS implications and professional careers.

Note: * The mean difference is significant at 0.05.

Table 2.15:Comparisons between employee satisfaction and professional careers.

Note: * The mean difference is significant at 0.05.

2.6Discussion and conclusions

The results of the study show that modifications to units that arise from the certification process can be grouped into internal changes, which are related to the units’ management and functioning and to the quality of services provided, and external changes, associated with the promotion of the units’ image and concern for customer satisfaction. In fact, the main changes resulting from a QMS implementation and certification seem to be related to the organization, mainly the units, and to the job.

Regarding interactions of the QMS implementation and certification on HRM, in the certified service units the changes seem to be felt largely in connection with job planning (e.g., increased formalization of internal procedures, work planning became more rigorous). Training issues were also indicated once respondents reported the units’ concern with such issues and access to more training opportunities.

Specifically regarding implications for employees’ work, the results showed a perception of greater efficiency and individual effectiveness in performing the job, further guidance for quality, greater control, higher levels of motivation and accountability, but also an increased workload.

These results are somewhat in line with the existing literature regarding interactions between QMS implementation and HRM. Quazi and Jacobs [26] demonstrated ISO 9001’s impact on T&D. Prates and Caraschi [29] report the impact of ISO 9001 on HR – work responsibility, value given to the norm’s principles and to customer requirements, and T&D. In the present study, the units’ employees reported having experienced increased access to training opportunities and more hours of training, as well as an increased concern and awareness regarding the quality of service provided. Hassan et al.’s [27] study of employee perceptions of HR development practices concluded that companies with ISO certification had significantly higher ratings regarding the career system, which included HR planning, recruitment, performance evaluation system, and promotions, as well as the level of job planning and quality orientation. The current research shows similar results regarding job planning and quality orientation.

Concerning performance, research from Prates and Caraschi [29] assessing the impact of ISO 9001 on employee performance showed that this certification has a positive and significant impact in some functional areas. The units’ employees reported greater efficiency and individual effectiveness in performing their jobs, as well as further guidance for quality, greater control, and higher levels of motivation and accountability, which are indicators of performance. However, it is important to clarify here that the current performance evaluation system of these employees is strictly limited to legal constraints if they are civil servants. So they may not perceive the implications of a different performance evaluation in their professional lives (e.g., career progression, increased income). As such, the response to the items related to performance can be biased by these constraints.

Data analysis also revealed the existence of negative associations between education and the consequences felt by ASU, SSU, and DSU workers on job execution and performance, employee awareness of one’s own work, and work procedures and organization. In addition, there are significant differences between the ASU and the SSU in the degree of agreement regarding implications on job execution and performance, employee awareness of one’s own work, and on bureaucracy, where SSU employees reveal greater awareness of these consequences. There are also significant differences between the SSU and the DSU in relation to the consequences concerning work procedures and organization, where DSU workers reveal greater awareness of them. Although the collected data do not allow a precise justification for these differences, it is believed that they are related to the different levels of workers’ education and length of service when QMS was implemented, as well with the time QMS has been in place at the unit.

In fact, the SS and DS units are the ones that have been certified for a longer period of time (both in 2009). This can explain the significant differences in perceiving some QMS implications between the ASU and SSU, where the ASU went through the QMS processmore recently (2012) than the SSU. Regarding differences between the SSU and the DSU that might be explained by levels of education, the SSU has fewer educated employees compared to the other units. Correlations (Table 2.7) show an association between three dimensions of the implications of the QMS and education: regarding the work procedures and organization (C3), the dimension where the means are higher, it can be seen that the higher the education level, the more positive the perceptions of the implications of QMS.

Regarding career, data revealed significant differences between operational assistants and senior technicians in terms of the consequences of QMS on job execution and performance, with the first ones revealing greater agreement. Also, significant differences were found between the technical and operational assistants regarding consequences for work procedures and organization, with the technical assistants revealing greater awareness of the existence of these consequences. It is suggested that the differences are due to the specific characteristics of each career. In fact, in legal terms, these careers are distinguished by different functional contents and different levels of complexity that increase from the operational assistant career, through the technical assistant, and achieving the highest level of complexity at the senior technician level.

Finally, the certification implications on the units’ employee satisfaction were generally positive. Furthermore, there are significant differences in overall satisfaction between the ASU and SSU, in that SSU employees seem overall more satisfied. Significant differences were also observed in satisfaction with the unit’s management and functioning and in overall satisfaction regarding career paths: the unit managers seem to be more satisfied compared to other workers in specific careers. Again, even though the data do not allow for a definitive explanation of these differences, it is thought that they could be related to the different ages and maturity levels of workers regarding QMS implementation in the units. Similarly, the variances in satisfaction found in different careers are believed to be related to the different degrees of complexity and functional content.

Final Considerations

Few studies have addressed the relationship between quality (e.g., management, certification) and HRM, employee satisfaction, and performance. This small study may help to better understand how to analyze these issues, especially in a specific work context.

While it corroborates some of the findings of previous empirical studies on the impact of the ISO 9001 implementation and certification process, this study collected some new data that may facilitate understanding of the ISO 9001 phenomenon in organizations, mitigating difficulties in implementation and enhancing the benefits of the process. The data collected, especially with regard to employee satisfaction with ISO 9001 certification, may facilitate understanding of HRM design and intervention to improve individual performance and employee satisfaction. The levels of education and the exposure time to a QMS certification might be variables worth exploring in future cases.

This work was based on a case study, and its results are not easily generalized. However, from a management perspective of trying to do whatever is possible with existing resources, this study can inspire the design of specific organizational interventions in this area.

Bibliography

[1]Wickramasinghe V (2012). Influence of Total Quality Management on Human Resource Management Practices. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 29(8):836–850.

[2]Jiménez-Jiménez D, Martinez-Costa M (2009). The Performance Effect of HRM and TQM: A Study in Spanish Organizations. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 29(12):1266–1289.

[3]Yang C-C (2006). The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on The Implementation of Total Quality Management: An Empirical Study on High-Tech Firms. The TQM Magazine 18(2):162–173.

[4]IPQ (2005). NP EN ISO 9000: 2005. Sistemas de Gestão da Qualidade. Fundamentos e vocabulário. Caparica: Instituto Português para a Qualidade.

[5]IPQ (2001). NP EN ISO 45020: 2001. Normalização e Atividades Correlacionadas: Vocabulário Geral. Caparica: Instituto Português para a Qualidade.

[6]ISO (2014). The ISO Survey of Management System Standard Certifications. http://www.iso.org/iso/iso-survey, retrieved in October 14, 2015.

[7]Sampaio P, Saraiva P (2011). Barómetro da Certificação. Um Retrato da Certificação de Sistemas de Gestão em Portugal. Qualidade, 12–19.

[8]Lopes M (2015). Certificação ISO 9001 e Gestão de Recursos Humanos: Precedentes e Consequentes. Estudo de Caso das Unidades de Serviços Certificadas da Universidade do Minho, Master Thesis in HRM. University of Minho, School of Economics and Management, http://hdl.handle.net/1822/40975.

[9]Juran J (1974). Quality Control Handbook. NY: McGraw-Hill.

[10]Crosby P (1979). Quality is Free: The Art of Making Quality Certain. NY:McGraw-Hill.

[11]Deming W (1994). The new economics for industry, government, education. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

[12]Tribus M (1993). Quality Management in Education. The Journal of Quality and Participation 16(1):12.

[13]Martínez-Lorente AR, Dewhurst F, Dale BG (1998). Total Quality Management: Origins and Evolution of the Term. The TQM Magazine 10(5):378–386.

[14]Yong J, Wilkinson A (2002). The Long Winding Road: The Evolution of Quality anagement. Total Quality Management 13(1):101–121.

[15]AEC (2013). Malcolm Baldrige. http://www.aec.es/web/guest/%20centro-conocimiento/malcolm-baldrige, retrieved in November 14, 2014.

[16]Vouzas F (2007). Investigating the Human Resources Context and Content on TQM, Business Excellence and ISO 9001: 2000. Measuring Business Excellence 11(3):21–29.

[17]APCER (2010). Guia Interpretativo NP EN ISO 9001: 2008. Leça da Palmeira: Associação Portuguesa de Certificação.

[18]EFQM (s/d). The EFQM Excellence Model. http://www.efqm.org/the-efqm-excellence-model, retreived in November 14, 2014.

[19]IPQ (2008). NP EN ISO 9001: 2008. Sistemas de Gestão da Qualidade – Requisitos. Caparica: Instituto Português para a Qualidade.

[20]Bayo-Moriones A, Merino-Díaz-de-Cerio J (2002). Human Resource Management, Strategy and Operational Performance in the Spanish Manufacturing Industry. m@n@gement 5(3):175–199. [21] Jones G, George J (2010). Essentials of Contemporary Management. Ryerson: McGraw-Hill.

[22]Deming W (1992). Out of the Crisis. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

[23]Bayo-Moriones A, Merino-Díaz-de-Cerio J, Escamilla-de-León S, Selvam R (2010). The impact of ISO 9000 and EFQM on the use of flexible work practices. International Journal of Production Economics 130(2011):33–42.

[24]Hassan A (2009). ISO Certification and Human Resource Management. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 52(2):285–301.

[25]Douglas A, Coleman S, Oddy R (2003). The case for ISO 9000. The TQM Magazine 15(3):316–324.

[26]Quazi H, Jacobs R (2004). Impact of ISO 9000 Certification on Training and Development Activities. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 21(5):497–517.

[27]Hassan A, Hashim J, Ismail A (2006). Human Resource Development Practices as Determinant of HRD Climate and Quality Orientation. Journal of European Industrial Training 30(1):4–18.

[28]Rodríguez-Antón J, Alonso-Almeida M (2011). Quality Certification Systems and Their Impact on Employee Satisfaction in Services with High Levels of Customer Contact. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 22(2):145–157.

[29]Prates G, Caraschi J (2014). Organizational Impacts due to ISO 9001 Certified Implementation on Brazilians Cardboard Companies. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 4(5):500–513.

[30]Universidade do Minho (s/d). Informação institucional. http://www.uminho.pt/uminho/informacao-institucional, retrieved in January 04, 2014.

[31]Universidade do Minho (2014). Relatório de Atividades e Contas Individuais 2014. http://www.uminho.pt/docs/relat%c3%b3rios-de-actividade/2015/06/11/uminho_2014_indi%20vidual_web.pdf, retrieved on October 20, 2015.

[32]Universidade do Minho (2010). Regulamento Orgânico das Unidades de Serviços da Universidade do Minho (aprovado pelo Despacho RT-49/2010, de 26 de abril). https://intranet.uminho.pt/Pages/Documents.aspx?Area=Despachos,%20Circulares%20e%20Delibera%C3%A7%C3%B5es, retrieved in January 04, 2014.

[33]Universidade do Minho (2009). Regulamento Orgânico dos Serviços de Ação Social da Universidade do Minho (aprovado pelo Despacho RT-46/2009, de 31 de julho). https://intranet.uminho.pt/Pages/Documents.aspx?Area=Despachos,%20Circulares%20e%20Delibera%C3%A7%C3%B5e, retrieved in January 04, 2014.

[34]Judge TA, Klinger R (2008). Job Satisfaction: Subjective Well-Being at Work. In: The Science of Subjective Well Being, Eid M, Larsen R (eds) (NY:Guilford press), 393–413.

[35]Bilhim J (2006). Teoria Organizacional: Estruturas e Pessoas. Lisboa: Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas.

[36]Cunha M, Rego A, Cunha R, Cabral-Cardoso C (2007). Manual de Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão. Lisbon: Editora RH.

[37]Bateman T, Snell S (2012). Management. NY: McGraw-Hill.

[38]Domingues I (2009). Gestão de Recursos Humanos em Processos de Mudança: Possibilidades e Dificuldades. In Tecnologia, Gestão da Qualidade e dos Recursos Humanos: Análise Sociológica, Domingues I, Neves J (eds) (Ermesinde: Edições Ecopy), 16–44.