1 Globalization and InterculturalManagement

1.0 Statement of the problem

Globalization and Business issues

(Julia Serdyuk)

Globalization eliminates the boundaries between the countries and provides new opportunities for business: want to open a subsidiary in Egypt? Go ahead! Want to sell your shoes of high quality in Kazakhstan? You can try! However, as the reality shows, it is not that simple and in many cases cultural differences, including differences in management style, can prevent the success of a joint venture.

In spite of all the differences between business cultures, we cannot neglect certain common grounds that constitute business in general. For example, each business deals with profit-orientation, professional development of staff, etc. And, thanks to globalization, today various countries can share and learn from each other in order to adopt new elements in their own operation. For example, Japanese companies now seem to be picking up lessons from American management to become more flexible and less avoiding uncertainty; American companies are learning best practices from their counterparts in other parts of the world, especially from Japan.

Having been off the market for many years, and under the pressure of “command” authority, Russia had difficulties to enter the world market. While globalization was already involving all other countries, it did not “touch” Russian business and management style until the 90’s, when the country started reforming its own business style. Now, Russia constitutes a part of the business world and is interconnected with the world system. Russia adopted some well-known management models as well as developed its own business strategies. What model of business style has Russia chosen? It is hard to define the model itself, as it is still being developed, but we can characterize Russian management style as more autocratic than democratic. Although the tendency in management here is to get more people-oriented, less “power-oriented”, employees get more and more appreciation for their knowledge, experience, and creativity. They are also given more choices and responsibilities at the workplace. I think, this indicates the development of a new management style, which has more similarities with American and European ones.

To summarize, globalization provides many opportunities as well as challenges in business. In order to better utilize the opportunities for different countries to operate successfully, under the conditions of cultural diversity, we need to go beyond our cultural stereotypes. Curiosity, openness and striving to reach mutual understanding should become good features for intercultural management. We can learn a lot from each other, but we need to learn to be tolerant and respectful to all the differences we face, when we do business together.

In: Cross-Cultural Blog: management style and globalization, in web:

http://web.stanford.edu/group/ccr/blog/2009/02/globalization_and_business_iss.html, accessed 23/06/2014

1.1 “The Global Challenge”

Every day we hear it on the news, read it in the papers, overhear people talking about it, and in every single instance the word “globalization” seems to have a different meaning. So, what is globalization?

At the political and economic level, globalization is the process of denationalization of markets, politics and legal systems; it is the rise of global economy. At the business level, the process of globalization is when companies decide to take part in the emerging global economy and establish themselves in foreign markets. They adapt their products or services to the linguistic and cultural requirements of different nations. Then, they might take advantage of the Internet revolution and establish a virtual presence on the international marketplace. E-commerce has changed traditional business practices by providing direct international access to information and products.

Whatever their industry or country of origin, all companies are facing the same challenge to a greater or lesser degree: globalization. It is becoming more and more evident that companies need to plan ahead and anticipate coming developments if they are to be successful in the future. Ecological matters have gained in importance at the turn of the century. Climate change is perceived as the biggest challenge to mankind and affects all industries and societies alike (Stern, 2008, p. 1).

In the past, it was primarily reductions in tariff and trade barriers that stimulated global trade and encouraged the integration of international business. Today, however, the key factor is the global networking that has been made possible by new communication technologies. Increasingly intense international competition is accelerating structural change throughout the world. More and more, industries that only “yesterday” limited their production to the United States, Europe or Japan are feeling the influence of threshold countries. Moreover, jobs that seemed guaranteed for life some years ago are moving into these low-wage countries. No longer are they limited to the production of simple toys for children – today companies in threshold countries are producing luxury consumer goods, consumer electronics and highly sophisticated machines and vehicles, and with dizzying success (Lippisch/Köppel, 2007, p. 3).

In order to be economically successful in the global market, it is not only the hard facts that count – such as the general economic and commercial settings, product quality or innovative products and services. “Soft” competencies, especially social competence and excellent communication skills, become more and more important. Thus, a balanced consideration of hard facts and “soft” competencies is increasingly becoming a prerequisite for global success. Only companies and organizations with a multicultural structure will succeed beyond the regional level and will continue to be successful on a global scale. In the future, mono-structures and mono-cultures will be limited to regional importance. However, multicultural organizations will not prosper automatically, just because they are multicultural. On the contrary, if managed badly, they may function worse than mono-cultural organizations. Thus, the skills to lead a multicultural organization have to be in the focus and are paramount for the success in the global market.

These consequences of global competition are putting pressure on companies in the developed Western countries. Companies from Central and Western Europe are faced with the question of how to respond in order to remain competitive. Market isolation is a strategy that no longer works in today’s globalized world, and it is likely to do more harm than good.

Instead, today it is crucial to establish a solid competitive position in the global arena and to defend that position by continually adapting to meet the needs of the market. There is no doubt that a corporate culture that is open to innovation and shaped by global thinking plays a key role in this context, a culture in which representatives of different countries and cultures can come together, while giving due regard to the developments and conditions that influence a company’s actions (Lippisch/Köppel, 2007, p. 3). International business and professional activity demand movement beyond one particular cultural conditioning into a transcultural arena.

The technological environment surrounding businesses today is characterized by a soaring speed of change and innovation. Revolutionizing innovations in the fields such as microelectronic, robotic and generic engineering can be perceived as a threat or chance to the enterprise’s competition (Welge/Al-Laham, 2008, p. 295).

If globalization refers to the transmission of ideas, meanings and values across world space the intercultural aspect is obvious. In the contemporary period, and from the beginning of the twentieth century, this process is marked by the common consumption of cultures that have been diffused by the Internet, popular culture media, and international travel. This has added to processes of commodity exchange and colonization which have a longer history of carrying cultural meaning across the globe. The circulation of cultures enables individuals to partake in extended social relations that cross national and regional borders. The creation and expansion of such social relations is not merely observed on a material level. Cultural globalization involves the formation of shared norms and knowledge with which people associate their individual and collective cultural identities. It brings increasing interconnectedness among different populations and cultures (Steger/James, 2010, p. 12).

As far as global challenges are concerned, the current developments can be split into four main categories (Rothlauf, 2004, pp. 25ff), namely:

- new technologies

- new markets

- new environmental drivers

- new global players

Within this framework, an intercultural answer has to be given, which includes:

- new corporate culture

- new skills

- new management and working styles

- new company structures

Both, challenges and the intercultural answers will be presented in the following and are also illustrated in Fig. 1.1.

1.1.1 Global challenges

New technologies

New information and communication technologies, such as the internet, are ubiquitous and cheap; they control the markets, permit worldwide access to information, foster global trends and reach the most distant corner of the world.

Moreover, an emerging technology as distinguished from a conventional technology is a field of technology that broaches new territory in some significant way with new technological developments. Examples of currently emerging technologies include educational technology, nanotechnology, biotechnology, cognitive science, robotics, and artificial intelligence.

Business is always changing and to maximize the relevant business options one have to explore new markets and to expand the current buiness activities. As resources become scarcer and scarcer and domestic markets are reaching the saturation point, it is becoming increasingly important to open up new sales, resource and labor markets. A successful search for geographic or technical alternatives is part of a company’s international strategy. Moving into new territories and categories is a radical strategy that can create major potential for incremental business growth. To succeed it requires a precise understanding of market dynamics, consumer behaviour and the competitive landscape of the specific markets.

New global players

Companies from threshold countries are developing at a breathtaking speed. They have the benefit of a plentiful supply of cheap, motivated and well-qualified workers. They are developing an increasingly accurate sense of where the demand is, and their ability to offer high-quality products at a reasonable price is growing as well.

A good example for those new global players is BRICS, an acronym for an association of five major emerging national economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. The BRICS members are all developing or nearly industrialised countries, but they are distinguished by their large, fast-growing economies. Moreover more and more developing countries are now entering the international stage and will play a larger role in the future.

New environmental drivers

Climate change and energy supply concerns are the primary drivers in the present debate. It has now been scientifically proven that climate change is triggered off by the emission of anthropogenic greenhouse gases; first and foremost CO2. In order to find adequate solutions to meet the manifold environmental need an urgent global response is demanded. The growing pollution all around the world has to be taken into account and the focus of all business activities should move to a higher environmental commitment of all parties involved in this context. In the long run, only those enterprises will survive that have the right answer in this very challenging field and can offer environmentally friendly products and services.

The Global Toothbrush

(Ralf Hoppe)

How many employees does it take to manufacture a toothbrush? Forty-five-hundred employees, 10 countries, five time zones.

Philips and its suppliers produce the electronic toothbrush “Sonicare Elite 7000” and its sister models at 12 locations and in five time zones. Once or twice a week, some 100,000 fully-functioning circuit boards leave the Manila factory. From Manila’s cargo airport they are flown via Tokyo to Seattle. A half day’s delay can wreak havoc in the entire system with a minimum of inventory and extremely tight timelines.

The toothbrush is essentially comprised of 38 components. The parts of the energy cell, a rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery, are supplied by Japan, France and China. The circuit board, its electronic heart, comes pre-etched from Zhuhai in the Pearl River delta of south eastern China. The copper coils originate from the Chinese industrial city of Shenzhen, not far from Zhuhai. They are wound by armies of women with bandaged fingers. Globalization is largely a female phenomenon.

The 49 components on the board – transistors and resistors at the size of match heads –hail from Malaysia. They are soldered and tested in Manila. Then they are flown to Snoqualmie on the West Coast of the U.S., the site of the parent plant. Meanwhile, back in Europe, the more complicated plastic parts are trucked from Klagenfurt in Austria to Bremerhaven in Germany. Klagenfurt also supplies blades made of special steel produced in Sandviken, Sweden. A freighter from Bremerhaven takes the half-finished brushes across the Atlantic to Port Elizabeth, New Jersey. From there they cross the continental United States by train. And in Snoqualmie, a 40 minute drive from Seattle, the final product is assembled and packaged.

Philips is a Netherlands corporation. But there are only two Dutch citizens among the 120 on this carousel of cultures and continents. The foreman in Snoqualmie comes from Gambia. Bernard Lim Nam Onn, the boss in Zhuhai, is Chinese, but was born in Malaysia and raised in Singapore. There are Irish, Ukrainians, Indians, Cambodians, Vietnamese, Thai. Globalization is carving out new biographies and cross-referencing them around the world.

In: Spiegel Special – International Edition, Nr. 7/2005, pp. 130ff

1.1.2 The intercultural answer

Given the variety of challenges, the solution must vary as well. Apart from technological solutions, a specific view on the so-called soft factors enables us to get a better understanding of how the problems can be solved in the future (Lippisch/Köppel, 2007, p. 8).

New company structures

Among the ways in which companies seek enhanced flexibility to meet the challenges of increasingly volatile markets are the outsourcing of certain services that were not marketable in the past. This market-driven increase in flexibility needs to be applied at the operational level; corporate structures as well as management methods need to be adapted to meet the needs of the future.

New management and working styles

The push towards increasing flexibility, accompanied by an increasing acceptance of personal responsibility continues in processes at the human level: decentralization, fluid company borders, globally organized added value and constant change require alterations in management and work models as well. The relevant demands must be taken into account in employment relationships, work-hour arrangements, incentive systems and further training programs, especially intercultural training programs.

Global managers work with people who have very different ideas about how business gets done. They must understand and adapt to country differences in unions, corporate governance, political legislation, investment policies etc. that can have an impact on business.

Moreover, global managers have to be fully aware of the complexity of norms, beliefs, values and attitudes that distinguish one cultural group from another. Working globally, managers must address multiple and differing expectations about how people (employees, colleagues, customers, suppliers, distributors, etc.) should behave, and how work should get done. Given the cultural diversity of our world, this is an extremely challenging task and requires a new thinking as far as the relevant working style is concerned. Today’s leaders need to adapt to leading and managing people of different cultures. Cultural differences impact everything from inter-personnel communication to health and safety procedures to project management. In short, no corner of any business escapes.

New skills

In globally active companies it is becoming more and more important that each employee shows personal initiative; they also need to be able to adapt their tasks to the changing demands within and outside the company, in order to meet the challenges of global business. Economically-driven diversity management is one way of ensuring that the various available human resources are used and combined in a manner appropriate to the specific situation.

As with all businesses success depends upon effective cooperation and communication within a company, particularly within multicultural teams. Therefore, business structures have to be radically transformed in the given context. Changes in areas such as communication and information technology and shifts towards global interdependence are obvious and having resulted in companies that are becoming increasingly international and as a logical consequence more and more intercultural.

New corporate culture

A global mindset and an innovative spirit should be made an integral part of the company and its corporate culture. Executives and employees, who understand global contexts and the need for innovation as well as its consequences for their own behavior, are crucial for establishing such a corporate culture. Furthermore, a company’s leadership has a responsibility to encourage, communicate and implement a continuously developing corporate culture with a specific focus on newly formed multicultural teams. Establishing and implementing ethical principles constitutes a major challenge in this context – all the more so because such principles need to be internationally applicable, binding and interculturally accepted.

“The magic in the globalization of the last years

is the mixture of different cultures.”

(Matthew Emmens)

Wolfsburg’s Gateway to Asia

We were slowly getting to know our Chinese partners in exciting discussions concerning special topics and were developing perspectives for Shanghai VWs together. When we were taking a look at the largely automated body-shell manufacture in Sao Paulo, it quickly dawned on us all that we would not need all that many robots in the production process. In China, where there was no limit to a very cheap workforce, robots were only supposed to be employed where the precision of the human hand and the human eye did not meet the demands for the quality to be safeguarded that we aspired to.

In our Mexican plant in Puebla, which we visited afterwards, everything worked out a bit differently than in Brazil on account of conditions typical of each particular country. Thus our Chinese fellow travellers got the impression of a capability of adaptation on the part of our concern to the different cultural and social conditions prevailing in each country concerned.

Then we headed for Tennessee, whereto the Japanese had succeeded in exporting their kind of car production to the USA. One of the first “transplants” – that was the term given to these manufacturing plants – was the subsidiary of Nissan in Smyrna, a small town near Nashville. Here, the Japanese had managed to adapt their legendary production system –cost-effectively, swiftly and quality-consciously – to US conditions and, at the same time, to establish a totally different cultural constellation successfully. We realised that in the factory halls of Shanghai Volkswagen two cultures would come together. Will we succeed in mediating constructively and productively between cultures, something that experts term as “Cross Cultural Management” nowadays?

In: 1000 Tage in Shanghai, 2006, p. 25 (own translation)

1.2 Intercultural management

The economic globalisation, the technological progress and the revolution of the information and communication technology sector have facilitated the communication among people around the world. While the psychology and sociology have reacted by studying the relations deriving from cultural exchanges, the economy developed a new discipline in the 1970s – the intercultural management – aimed at adapting the marketing rules to the specific cultural characteristics of a target market. Since then, the scope and object of study have been expanded to include the management at the level of organisations operating in a multi-cultural environment, especially for companies operating branches outside the country of origin. Consequently, the intercultural management has rapidly developed the notions of mother-culture versus enterprise-culture. The first element is specific for the country from which the company originates, while the second is specific for the country in which the company opens its branch. In order to avoid possible cultural conflicts, the intercultural management uses specific tools and methods that mediate between two or more cultures.

1.2.1 Definition of intercultural management

Intercultural Management can be described as a combination of knowledge, insights and skills which are necessary for adequately dealing with national and regional cultures and differences between cultures at several management levels within and between organisations (Burggraaf, 1998). It is not a separate subject but an integral part of general and international management.

Intercultural Management interleaves with international management as some similarities occur. It might therefore be relevant to depict those features of international management that are effective. These features are:

- Teams consist of internationally representative managers

- Structural forms such as organic modes exist

- Leadership includes varied skills appropriate for the global context

- Motivation is appropriate for diversity

- Organisational cultures such as those characterising learning organisations exist

- Communication methods and systems are available and applicable

- Human resource management systems and practices that reflect the dynamic of operating in the global context are used (Jacob, 2003)

As part of the term intercultural management the expression management is ubiquitous. Management is the on-going professional composition, steering and development of (complex) structures and processes in order to achieve the goals of the organisations. (Koch, Speiser, 2008)

For a definition of intercultural management the general management definition needs to be extended by the cultural component. Therefore, intercultural management can mean to achieve goals with professional means by persons of other or different cultural influence. It is the composition, steering and development of structures and processes in order to achieve the goals of an organisation in a context that is shaped by the coincidence of at least two different cultures. (Koch/Speiser, 2008)

1.2.2 The importance of intercultural management

If you agree with Elashmawi/Harris (1993, p. 1), who say that “the new world market will not only be international, but intensely intercultural”, it will become obvious that the international management of the future will also – or even particularly – make the inclusion of intercultural management an absolute necessity. Hambrick/Snow (1989, pp. 84ff) arrive at a similar conclusion and say:

“Integration and human resource management are dependent upon one another to the degree that structuring a firm’s global activities involves the deployment and use of human capital and other human aspects.”

The need for a specific intercultural discipline in the management field comes from the fact that speaking a foreign language is not enough for a sufficient communication between people belonging to different cultures. The surface of a process is much more complex than the simple understanding of what the other says. This is because the communication is not linear, which means that the transmission of a message is never neutral; the spoken message transmits words and notions, but also norms and values and some of these norms and values may not be fully shared by the dialogue partner. (Meunier/Zaman, n.y.)

Consequently, managers have to be aware not only of the different language of the business partner but their diverging attitude, time perception, behaviours, traditions and further aspects related to a different culture. At this point, intercultural management provides the opportunity to be aware of it and deal with such cultural aspects. Failures in one’s behavior while doing business or misunderstandings of the business partners’ actions can lead to severe problems and even a termination of the partnership.

Intercultural Management in China

In a study dealing with intercultural management in China conducted by students of the University of Applied Sciences in Stralsund, 37 companies from China and Germany participated filled in the survey. The results show that the majority of companies consider intercultural management as very important for their German-Chinese business relations.

Question: Do you think intercultural management in China plays a crucial role in doing your business successfully? If yes, why?

(extract)

- – Different cultures implement different working styles which should be taken into consideration

- – Intercultural management can bridge the different understanding and thinking between people in China and Germany or Europe.

- – Proper understanding of local culture is essential for conducting business here. Otherwise, there will be certainly problems with communication.

In: Golz/Kerwin/Rimaite, Written Assignment, 2013 (unpublished)

In recent years, the intercultural management has become particularly important as the phenomena of globalisation has been accompanied by increasing migration flows, enlargement of the European Union, economic openness of many countries around the world, the emergence of new economies like China and the expansion of economic partnerships between countries disposing of different economic systems. The cooperation between these different economic systems, which are based on significant cultural differences, requires a new – intercultural – approach.

Another possibility of integrating intercultural thinking and acting into the existing curriculum can be seen in the job enlargement of international personnel management. Especially in Anglosaxon literature (Black/Mendenhall, 1990; Phatak, 1997; Teagarden/Gordon, 1994; Tung, 1981), strong reference is to be found. The authors share the opinion that

“these new roles include international extensions of more traditional human resource management support functions such as providing country-specific knowledge of union and labour policies, legal and regulatory requirements, compensation, and benefit practises. They include preparing people for international assignments, and re-entry after those assignments are completed.” (Teagarden/Glinow, 1997, p. 8)

30 TIPS ON HOW TO LEARN ACROSS CULTURES (1-2)

(Andre Laurent)

- Be aware of your own very special culture as a unique peculiarity. When working across cultures you will often be the “stranger” – perceived by others as being “strange”.

- The culture that you ignore most – in terms of its shaping power on yourself – is obviously your own culture. It is very difficult to look at oneself from the outside. We can make interesting observations and comments about other cultures. But we often remain blind to our own.

In: SIETAR (Hrsg.), Keynote-Speech, Kongress 2000, Ludwigshafen

For companies, this approach means that the consideration of the intercultural issues of all cross-border activities must no longer be neglected. Far more than before, these issues have to explicitly find their way into the respective activity’s intercultural orientation. (Perlmutter, 1965, p. 153)

Those who want to succeed on international markets have to deal with unprecedented problems, which result due to the mere fact that there is contact with foreign countries, cultures as well as economic and social structures. However, an explicit implication of those factors does not happen in most cases. At this point, intercultural management comes into place.

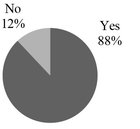

At the University of Applied Sciences Stralsund, a study was conducted by the four students Carolin Boden, Elisabeth Guth, Nelly Heinze and Sarah Lang, who questioned 22 consulting companies and experts about the influence of cultural aspects on the failure of mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The results underline the importance of intercultural management and training during the M&A process, but can be transferred to other fields as well.

Fig. 1.3: Importance of intercultural training for international M&A

Source: Boden/Guth/Heinze/Lang, 2011, p. 81

1.2.3 The tasks of intercultural management

The discussion, whether the topic of management has to be seen in a “culture-bound” (hypothesis by culturalist respectively cultural relativists) or “culture-free” context (hyphothesis by universalists), has shown that the majority – according to Hofstede (1993) – considers management as a culture-bound phenomenon. Hence, a particular sensibilization for cultural phenomena is required. (Kumar, 1988, pp. 389ff, Kiechl, 1997, p. 16)

While a few scientists (Thomas, 1996; Kiechl, 1990) have pointed out a global convergence and have consequently ruled out a connection between ethnoculture and corporate culture, the majority of scientific studies (Adler, 1983; Perlmutter, 1965; Hofstede, 1993) verify that undertakings in different nations reveal different corporate cultures, which can be traced back to the respective ethnocultures. At internationally active companies, the ethnocultural influence on the corporate culture, which depends on the nature of the relationships between the subsidiaries and the parent company and between the different subsidiaries, can be monitored and to a certain degree even steered (Kiechl, 1997, p. 14).

Race

(Barack Obama)

As the child of a black man and a white woman, someone who was born in the racial melting pot of Hawaii, with a sister who’s half Indonesian but who’s usually mistaken for Mexican or Puerto Rican, and a brother-in-law and niece of Chinese descent, with some blood relatives who resemble Margaret Thatcher and others who could pass for Bernie Mac, so that family get-togethers over Christmas take on the appearance of a UN General Assembly meeting, I’ve never had the option of restricting my loyalties on the basis of race, or measuring my worth on the basis of tribe. Moreover, I believe that part of America’s genius has always been its ability to absorb newcomers, to forge a national identity out of the disparate lot that arrived on our shores.

In: The Audacity of Hope, New York 2006, p. 231

One can conclude that the task of intercultural management includes the concrete design of functional, structural and personnel management processes. Its aim is to facilitate a successful overcoming of management problems by providing adequate approaches for efficient international actions. (Perlitz, 1995, p. 318) Therefore, professionals and executives of internationally operating companies do not only need legal, technical and economic expertise and speak foreign languages but also have to adjust their behavior to intercultural standards which enable them to work effectively in a foreign environment.

Whoever wants to remain internationally successful has to be able to assess anticipatorily the impacts of cultural differences on management practices, individual work attitudes, communication, the conduct of negotiations etc. (Weidmann, 1995, p. 41) However, this way of thinking may not be seen as a one-way street. The necessity to observe and apply intercultural principles and behavior is not only vital for external business relations but also for internal business processes.

In future, one can assume that the number of business meetings where participants come from different cultural backgrounds will increase (Mauritz, 1996, p. 1). For German companies, this development means that they will have to integrate more employees from other cultures into the company – regardless whether they work at the corporate head office or at foreign subsidiaries. The new questions and solution approaches involved are also part of intercultural management.

Connecting Intercultural Communication and Management

(Gary R. Weaver)

The workplace of the new millennium will be multicultural and global. With greater intercultural interaction, the differences are not simple going to disappear. We will not link arms in the office, sing “We are the World”, and find that we can easily overcome the communication breakdowns or conflicts. As long as we remain within our own culture, we take it for granted. However, when we leave it and interact with people from other backgrounds, we become more consciously aware of our own culture, and it becomes more important to us.

In: Intercultural Management Institute, Washington, DC, Nr. 9, 2001, S. 3

1.2.4 Challenges in the field of intercultural management

Similarities of social habits, tastes and exposure might make managers across nations more homogeneous, but there are still differences coming from cultures that have to be considered. Quite a bit of intercultural management today deals with the construction of mechanisms for integration.

Today there is an increasing preoccupation about the leadership and management styles, which are appropriate for intercultural management. Another important point regarding the repertoire of abilities needed by global managers is to feel comfortable in culturally diverse teams. Cultural orientations are learnt behaviours. Therefore, managers can develop the flexibility and openness which is necessary to transit from one cultural context to another. This is part of the challenge when working for professionally managed and high performance companies. (Jacob, 2003)

Some of these challenges have been described by Nardon/Sanchez-Runde/Steers (2010, pp. 16ff):

“This evolution from a principally bicultural business environment to a more multicultural or global environment presents managers with at least three new challenges in attempting to adapt quickly to the new realities on the ground:

- It is sometimes unclear to which culture we should adapt. Suppose that your company has asked you to join a global project team to work on a six-month R&D project. The team includes one Mexican, one German, one Chinese, and one Russian. Every member of the team has a permanent appointment in their home country but is temporarily assigned to work at company headquarters in Switzerland for this project. Which culture should team members adapt to? In this case, there is no dominant cultural group to dictate the rules. Considering the multiple cultures involved, and the little exposure each manager has likely had with the other cultures, the traditional approach to adaptation is unlikely to be successful. Nevertheless, the group must be able to work together quickly and effectively to produce results (and protect their careers), despite their differences. What would you do?

- Many intercultural encounters happen on short notice, leaving little time to learn about the other culture. Imagine that you just returned from a week’s stay in India where you were negotiating an outsourcing agreement. As you arrive in your home office, you learn that an incredible acquisition opportunity just turned up in South Africa and that you are supposed to leave in a week to explore the matter further. You have never been to South Africa, nor do you know somebody from there. What do you do?

- Intercultural meetings increasingly occur virtually by way of computers or video conferencing instead of through more traditional face-to-face interactions. Suppose you were asked to build a partnership with a Korean partner that you have never met and you know little about Korean culture. Suppose further that this task is to be completed online, without any face-to-face communication or interactions. Your boss is in a hurry for results. What would you do?

Taken together, these three challenges illustrate just how difficult it can be to work or manage across cultures in today’s rapidly changing business environment. The old ways of communicating, negotiating, leading, and doing business are simply less effective than they were in the past.”

“Seven social sins:

politics without principles, wealth without work,

pleasure without conscience, knowledge without character,

commerce without morality, science without humanity,

and worship without sacrifice.”

(Mahatma Gandhi)

The Rise of Generation Global – Seizing opportunity in a world economy that ignores borders

My son Daniel is working in Vietnam marketing Budweiser beer, an American on. Budweiser may be as American as you can get, but it’s now owned by Anheuser-Busch InBev, a Belgium-based company. InBev itself was created a few years ago by the merger of a Brazilian company, Ambev, with Interbrew of Belgium.

That’s a lot of info to crowd into the top of a column, forgive me, but the modern world is a little like that: a tangled web of cross-border holdings where national icons are not really that national at all. Daniel, 27, is heading to Brazil for a month to train with Brazilian marketers on how to sell an American beer to the 80 million citizens of fast-growing Vietnam. He’s part of Generation Global (GG).

The existence of GG is a hopeful thing. Never before have so many young people been so aware of the shared challenges facing the globe, so determined to get “out there” to learn about it, or so intent on making a contribution to a more equitable world. The borderless cyber-communities of social networking have a powerful effect on their views. My son’s Vietnamese-Brazilian connection is interesting. That’s where the growth is. He’s American-educated, but if he’d stayed in the United States after completing his M.B.A. he might well have found himself joining the long line of twenty-somethings without a job. The growth that has helped avert economic meltdown since 2008 has come overwhelmingly from next-wave countries like China, Vietnam, India, Russia, Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa. These are the places on which multinational corporations are focused.

Now I’m for a more multipolar world because the United States simply does not have the resources to assume ad infinitum its current pivotal role in global security. But I’m also mindful that the worlds of 1914 and 1939 were multipolar – and produced cataclysm. Careful what you wish for is a useful maxim when radical power shifts, of the sort occurring today, are in progress.

The emergent powers represent a hodgepodge of systems and values, which is one reason their voices are indistinct, along with the fact that they are for now intensely focused on their own development. You have the authoritarian systems (in their different forms) of China, Vietnam and Russia; and the sprawling democracies (one old, one middle-aged, one newish, one new) of India, Brazil, South Africa and Indonesia. All, in varying degrees, have misgivings about the western-dominated world whose time is coming to an end.

Another thing they have in common is their burning desire to grow. Many of these nations know much from their own histories of the struggle for freedom (ongoing in Iran), for peace (ongoing in Israel-Palestine), for a national reconciliation (Afghanistan), for an end totalitarian misery (North Korea). How emergent powers assume the responsibility growth brings seems to me critical.

For now, they lag the corporations that knit the world closer and have landed my son in a Brazilian-Belgian-American-Vietnamese web. I’ll raise a glass to that particular exotic brew.

In: New York Times, 22nd February 2010, p. 2

1.2.5 The European Union and intercultural dialogue

Even the European Union has recognised the importance of questions related to intercultural management, which was reflected by the decision of the European Parliament and the Euro--pean Council to designate the year 2008 as the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue. This year recognises that Europe’s great cultural diversity represents a unique advantage. It encourages all those living in Europe to explore the benefits of its rich cultural heritage and opportunities to learn from different cultural traditions (interculturaldialogue 2008.eu.406.0.html).

The overall objectives of the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue aim to contribute to (Official Journal of the European Union, 30/12/2006):

- promoting intercultural dialogue aas a process in which all those living in the EU can improve their ability to deal with a more open, but also more complex, cultural environment, where, in different Member States as well as within each Member State, different cultural identities and beliefs coexist,

- highlighting intercultural dialogue as an opportunity to contribute to and benefit from aa diverse and dynamic society, not only in Europe but also in the world,

- raising the awareness of all those living in the EU, in particular young people, of the importance of developing an active European citizenship which is open to the world, respects cultural diversity and is based on common values in the EU as laid down in Article 6 of the EU Treaty and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union,

- highlighting the contribution of different cultures and expressions of cultural diversity too the heritage and ways of life of the Member States.

The specific objectives of the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue shall be to:

- seek to raise the awareness of all those living in the EU, in particular young people, of the importance of engaging in intercultural dialogue in their daily lives,

- work to identify, share and give a visible European recognition to best practices in promoting intercultural dialogue throughout the EU, especially among young people and children,

- foster the role of education as an important medium for teaching about diversity, increase the understanding of other cultures and developing skills and best social practices, and highlight the central role of thee media in promoting the principle of equality and mutual understanding,

- raise the profile, increase the coherence of and promote all Community programmes and actions contributing to intercultural dialogue and ensure their continuity,

- contribute to exploring new approaches to intercultural dialogue involving cooperation between a wide range of stakeholders from different sectors.

1.2.6 Intercultural management vs. cross-cultural-management

Some research approaches differentiate between an “intercultural” and a “cross-cultural” point of view. Intercultural studies concentrate on cross-border contacts and relationships, whereas “cross-cultural” studies compare certain phenomena in different cultural surroundings. (Koester/Wiseman/Sanders, 1993, p. 5)

On the one hand, works in culturally comparative psychology have e.g. proved that cultural factors have a big influence on psychological processes such as perception, motivation, cognition and emotion. Moreover, the results show that some psychological laws hold across cultural borders but also that such generalizations are not possible without restrictions. (Thomas, 1993, p. 387) Consequently, the “cross-cultural” perspective always generates comparative assertations, which means that the focus is on the cultural comparison.

Three Levels of cultural studies

(William B. Hart)

Cultural studies are done at three levels: Monocultural studies, cross-cultural studies, and intercultural studies. Monocultural or single culture studies are common in anthropology and sociology. Cross-cultural studies are studies that compare the characteristics of two or more cultures. Intercultural studies are studies that focus on the interaction of two or more cultures and answer the main question of what happens when two or more cultures interact (at the interpersonal level, group level or international level). The focus of intercultural relations is with the intercultural studies. Monocultural and cross-cultural studies cannot be ignored, however, because they serve as necessary precursors to intercultural studies.

In: The E-Journal of Intercultural Relations, Nr. 6, 1998, S. 1

On the other hand, the prefix “inter” is mainly used to decribe connections between individual units, especially in the context of border crossing. International encounters reach across national borders and intercultural contacts across cultural barriers. The relationships between social organizations are always of an intercultural nature, since every organization is by definition a specific culture which distinguishes itself from the culture of other organizations. If one however assumes that the use of the prefix “inter” – as is to be found e.g. in the words “inter”-cultural or “inter”-national management (Mauritz, 1996, p. 74) – implies an isolated view on cultures or nations, then this definition fails the holistic approach connected to cross-border interactions. Intercultural considerations can never be completely independent from comparative statements but need them as a basis in order to gain qualitatively distinguishable results. The actions of expatriate managers are influenced by their own as well as foreign moral concepts.

1.3 The expert’s view: Interview with Dr. Thomas Zenetti

Dr. Thomas Zenetti is the Head of the international Master program “Intercultural Management” at the Université de Haute-Alsace Mulhouse-Colmar (recorded 25/07/2014).

Rothlauf: In general, what are the reasons today to deal with questions related to intercultural issues?

Zenetti: In my understanding, it is all about the way you communicate with people from another culture. It is not enough to understand the language of your partner. Somebody from Great Britain thinks and behaves differently compared to a U.S. citizen, although they both speak English. I myself have made the experience that our neighbors from the German speaking part of Switzerland react completely different than we Germans. Related to our Master program, it is obvious that such an exchange between students from different cultures can only function if the peculiarities of each culture are taken into consideration. As relevant studies have clearly proven, the neglect of those intercultural issues will not only cause problems in private life but moreover in business life you will lose a lot of money.

Rothlauf: What were your fundamental ideas behind offering your students an international Master program entitled “Intercultural Management” and which kind of initial difficulties did you have to overcome?

Zenetti: Here, several factors play a role and come together: On the one hand, we have a literature and linguistics program in applied foreign languages on a bachelor level with a strong focus on business administration, on which we can build on. On the other hand, our university, located in the Upper Rhine region, has a pioneering role in cross-border programs, especially as far as interculturally designed working programs are concerned. As a logical consequence of all these facts, a Master degree program in intercultural management was the best answer. Still, it was not that easy to start with this program. It took a lot of hard work to get the support from the faculty, because the so-called “soft factors” of this program did not correlate with the ideas of classical business programs and the linguistics colleagues had to be convinced that we are not in concurrence to their existing programs but look for an interdisciplinary co-operation. In the end, we succeeded in bridging the gap, a really intercultural task.

Rothlauf: Where do you see the special feature of this course and what makes this program unique compared to other international programs, especially those that are offered in France?

Zenetti: First of all, it is the language program in combination with management courses. About half of the offered language courses are in French, at least 30 per cent in English and about 20 percent – depending on the selected elective courses – in German or Spanish. But if the students are interested in learning more languages, we give them the opportunity to learn, for example, the Chinese, the Japanese or the Russian language as well. This variety of languages we do offer is relatively rare in France, particularly at small universities. For such a program, we do not only need students with a good command of economics, an interest in learning three foreign languages, but also faculty members who are capable of transferring our ideas into reality.

Rothlauf: Who are the students that are enrolled in your Master program and what different nationalities are represented in this course?

Zenetti: It is clear that Mulhouse has not the same appeal as Paris or Lyon, but there is a steadily growing demand for this program that allows us to select our students accordingly. About 25 percent of all students are coming from outside France. So, we are happy to have not only students from the neighboring countries like Germany and Switzerland but also from Russia, China and from South America.

Rothlauf: How do the students work and live together? Different religious affiliations, different language levels, different notions of time and so on can cause a variety of problems. How do you cope with all those challenges?

Zenetti: We always analyze the situation and, in a joint effort, we are looking for a solution, sometimes with the help from members of the group itself, sometimes we offer support from our university. Let me give you an example: A female Russian student had been elected as the leader of a group and had distributed different tasks among the members of the group. She then got angry as the Chinese student did not stick to the deadlines. The problem was caused by an intercultural misunderstanding: A simple “niet” is not in line with the Chinese culture, where everybody tries to be in harmony, which means that the students tried to avoid to say “no”. At the end, however, they finished the project in a very successful manner.

Rothlauf: Are there any first reactions from the labor market and is it difficult for your graduates to find a job?

Zenetti: Ninety to ninety-five percent of our graduates get a job in the first three months after finishing this program. More than half of the students receive a job offer at the end of their six-month internship. Especially in a country like France with an unfortunately high rate of youth unemployment, we are proud to publish those figures. Moreover, the companies tell us that our concept is in line with their perception: instead of focusing on selected issues such as human resource management or project management, the variety of courses makes the difference. The linkage of intercultural aspects with language courses and a holistic approach to questions that are essential in business administration generate a program that is pretty well accepted by the companies.

Rothlauf: What are your personal experiences in this context?

Zenetti: As a German who has now lived for three and a half decades in France, I have got to know all the different stages of the acculturation process, without becoming a 100 percent Frenchman. It is very interesting to see how the theories of Hofstede, Hall and others are in line with my own experiences. Moreover, it is a wonderful opportunity for me to see the differences as well as similarities among our students coming from all around the world. To help them to get a more differentiated intercultural view is a challenging task and I am proud to be part of this program.

30 TIPS ON HOW TO LEARN ACROSS CULTURES (3–4)

- 3. Intercultural situations offer the unique opportunity to reduce our blind spot. Other cultures act as privileged mirrors in which we can see more of our own cultural makeup as a result of being confronted and challenged by other cultural models. This leads to greater understanding of the peculiarities of our own culture.

- 4. Don’t expect others to think and act as you do. Your culture – and therefore your own preferred way of getting things done – is just one among many. Expect others to think and act differently. Recognize that your way can be the exception rather than the norm.

In: SIETAR (Hrsg.), Keynote-Speech, Kongress 2000, Ludwigshafen

1.4 Case Study: Interviewing costumers in Asia –The impact of culture

The choice of the interview language is a very important aspect for cross-cultural research studies and it needs to be taken into account already in the pre-interview stage.

Relying on English as the only language in a global research limits the access to respondents. Furthermore, it might also result in the fact that data is collected from respondents who are fluent in English, but whose attitudes and behavior differ tremendously from the non-English speaking population.

Even between English-speaking countries, significant linguistical differences may occur. When interviewing Indian respondents, for example, it becomes clear that some words have a completely different meaning than in the UK. The word “sincere” which in England signifies “honest” and “true” and which refers to someone who “is honest and says what he really feels or believes”, is used in India to indicate someone who accepted responsibility. As the meaning of words is shared only by members of the same culture, people from different cultural background have a different understanding of the same word. Researchers, therefore, have to be aware of the fact that there exist many “Englishes” instead of the one English language. Consequently, when doing cross-cultural studies, it is crucial to compare equivalent expressions in all relevant languages in order to be able to identify the most appropriate term to fit into the respective context.

2. Individual interviews or focus groups

In many Asian countries, and especially in China, the predominant Confucian philosophy emphasizes the importance of the group. As a consequence, the unit of analysis of a qualitative research conducted in Asia might be the group itself and not the individual. This means that focus groups rather than the usual one-to-one interviews need to be carried out as almost all believes, attitudes and values of the respondents are a result of in-group interaction. By interviewing Chinese participants in groups, researchers can gain much deeper insights into their way of thinking than in individual interviews as people feel much more comfortable in a group setting which enables them to interprete and evaluate things collectively. It is, however, of great importance that the group under investigation is not randomly formed, but consists of members of the same peer group. In interdependent cultures, such as China, respondents will only express openly their opinion when the participants of the focus group are placed in the same position in hierarchy. Otherwise they feel obliged to agree with people from higher hierarchical positions and change their point of view.

Conducting focus groups in Japan bears some challenges. Compared to other countries, focus groups in Japan seem to be more structured. While some subjects with which respondents can easily identify themselves can generate lively discussions, other topics require a considerable amount of involvement on the part of the moderator in order to make participants talk. Japanese interviewees sometimes hesitate to share their thoughts and opinions if they feel that they are not in line with the group. This is due to the innate Japanese desire to maintain harmony. In case that the respondents’ opinions actually are in opposition to those of the group, they might even answer contrary to their own feelings and attitudes. The Japanese culture is a rather neutral culture in which people do not show their true feelings and desires openly; instead emotions are kept hidden as they may conflict with what society expects from the individual. “Tatemae”, literally meaning façade, is the behavior which is shown in public and which accounts for the fact that Japanese feel the obligation not to express their opinion freely if this could endanger the social harmony. For Western cultures which are more individualistic, this seems to be hard to understand since people are used to be very independent and do not have to render account to anybody for their behavior. In order to overcome the barriers which make conducting groups in Japan quite difficult, the number of participants in the group should be reduced to a minimum. This is necessary as the size of the group increases the pressure of conformity to group opinion enormously. Consequently, it is sometimes even advisable to conduct triads, a group consisting of only three people.

Source: Dahm, F./Schüle, U., in: UPDATE 12, SS 2011, p. 5–7

Review and Discussion Questions:

- What is the general message of this article?

- You are a European manager and currently working in Asia. Are there any significant hints you have to take into your consideration when doing business in this region?

- How would you transfer ideas from this article into your everyday business life with a specific view on working together with Japanese managers?

- Which kind of cultural information can you gain by taking a look at this article and compare the relevant information with your home country views!