6 Intercultural Communication

6.0 Statement of the problem

How to work with heavy accents

May Choi’s China Chef restaurant was located in an area where many of the customers were Mexican. Most of the restaurant employees were Chinese and could not understand or speak Spanish. One day a Mexican customer came in to order dinner. During the order, the Mexican asked for arroz – rice in Spanish. May Choi, who was taking the order, thought the customer was asking for “a rose” and directed him to a florist located in the same mall. After this incident, May Choi hired a number of Mexican employees who spoke both English and Spanish to help communicate with her Mexican customers.

In: Global Smarts: The art of communicating and deal making anywhere in the world, New York, 2000, p. 153

6.1 The importance of intercultural communication

Global communication is a major part of every international business. The success of every international business activity depends on the effectiveness of the communication with other cultures. Apart from the language differences, they need to focus on the social attributes, religion, attitudes and other facts from different cultures. All these communication terminologies are known as “Intercultural Communication”. Intercultural communication is not only about language but also about managing a different language. There are different understandings about culture and language in other countries. People travelling and living abroad should make an attempt to become familiar with the local culture and show respect, which will leave a positive impression and improve the relationship with the host. Moreover, using native-language slang and style in foreign countries is not recommended, because it will confuse listeners. Hence, it is always better for more effective communication to explain things in simple words. People should not judge the behavior of others on the basis of their own culture. People from different cultures e.g. have different ways of greetings and should understand diverse behaviors around the world for effective intercultural communication. Sheida Hodge responds to the question about the impediments of good communication:

“Problems with meaning are especially important in cross-cultural communication. What you mean when you say something is not necessarily what the other side hears. Messages derive a large part of their meaning from their cultural context. In a cross-cultural communication, messages are composed or ‘coded’ in one context, sent, and then received or ‘decoded’ in another cultural context.” (Hodge, 2000, p. 145)

The communication process and the influences of different cultures will be explained in more detail with the help of a communication model in the following.

6.2 The communication model

Communication can be defined as the process of transmitting meanings (Blom and Meier, 2002, p. 73). Gibson (2002, p. 9) also states that communication is the exchange of meaning, involving the sending and receiving of information between a sender and a receiver. This happens not only through words, but also non-verbal factors are involved. The problem iss that the message received can be very different from the message that was sent. Adler (1991, p. 64) even states that “(…) the sent message is never identical to the received message”.

A common model for communication is as follows:

The idea or feeling is sent by the source by putting it into symbols. Several conditions influence the communication capacity, for example his/her communicative capabilities and his/her socio-cultural system, which disposes of implicit norms and values that influence the message (Blom and Meier, 2002, p. 75). The message is transmitted through a channel. A channel is a medium used for communication, for instance emails, letters, telephone calls or face-to-face conversations (ibid.). Then, the message is interpreted (decoded) by the receiver, who responds. To see if the message has been understood, one has to measure the reaction and the feedback of the receiver (ibid.). The context is seen as the general environment, also called extra-verbal communication level (Hasenstab, 1999, p.154), in which the communication takes place. Noise means anything that distorts the message. To see if the communication has been effective one has measure

“(…) the degree to which a message is received and understood, and if the receiver’s ’s reaction to the message correspond to the sender’s purpose in sending it. ”(Tosi et al. 1990, pp. 450f)

Intercultural communication takes place when the sender and the receiver are from differing cultures, meaning

“(…) the process of communication between individuals from different cultures” (Jacob, 2003, p. 72).

Communication can be very difficult if there is a big difference between the two cultures. Hence, if there is too much “cultural noise”, communication can fail (Gibson, 2002, p. 9).

Intercultural communication generally involves face-to-face communication between people from different national cultures. The main personal traits that affect intercultural communication are:

- self-concept (refers to the way in which a person views his- or herself);

- self-disclosure (refers to the willingness of individuals to openly and appropriately reveal information about themselves to their counterparts);

- self-monitoring (refers to the use of social comparison information to control and modify one’s self-presentation and expressive behavior);

- social relaxation (the ability to reveal only little anxiety in communication).

Effective communicators must know themselves well and, with the help of their self-awareness, initiate positive attitudes. Individuals must express a friendly personality to be competent in intercultural communication. (Jandt, 2013, pp. 35f)

Nowadays, the telecommunication revolution permits rapid correspondence with business partners around the world. Communication via fax, telex, e-mail, cell phone and video conferencing enables us to constantly stay in touch with our international counterparts. Nevertheless, these technological marvels have not eliminated the need for face-to-face contact with our relationship-focused customers and partners. Relationship-focused people are less comfortable to discuss important issues in writing or by phone. They expect to see their suppliers and partners in person more often than is considered necessary in “deal-focused” markets. (Gesteland, 2002, p. 29)

6.3 Negotiating across cultures

Namaste is a common greeting used on the Indian subcontinent. Literally translated it means “I bow to you” and is used to express deep respect by Hindus, Jains and Buddhists in India and Nepal. In these cultures, the word is spoken at the beginning of a conversation, accompanied by a slight bow made with hands pressed together, palms touching and fingers pointed upwards, in front of the chest. As such, Namaste is a form of both verbal and non-verbal communication. It may be only one word, but it carries significant symbolism.

Within one culture or language group, communication can often be problematic – generally across age groups, geographic regions and gender. However, these problems pale in comparison to the challenges of communicating across cultures. (Nardon/Sanchez-Runde/Steers, 2010, p. 200) However, most researchers, employees, and business owners agree that the most important element in effective intercultural communication is language.

“Language issues are becoming a considerable source of conflict and inefficiency in the increasingly diverse work force throughout the world [...]. No corporation can be competitive if co-workers avoid, don’t listen to, perceive as incompetent, or are intolerant of employees who have problems with the language. In addition, these attitudes could be carried over into their interactions with their customers who speak English as a second language, resulting disastrous effects on customer relations and, thus, the corporate bottom line.” (Fernandez in: Hillstrom, in web)

Some Notes on Business Meetings

- Chinese organizations typically request background information before they agree to formal discussion. Provide as much information as possible about the individuals who will present, the organization you are representing, and the topic you wish to discuss, and give the Chinese time to study the request.

- In China, meetings are generally held in conference rooms rather than offices. Seating is not rigid, but there typically are designated places for the principals.

- Punctuality is considered a virtue, so it is important to arrive at a meeting on time –not late and not early. Guests are greeted upon arrival by a representative and escorted to the meeting room.

- Chinese generally expect foreign delegation leaders to enter a room first, and this prevents confusion. Important guests are escorted to the seats, which the principal guest placed in a seat of honour.

- Chinese meetings begin with small talk.

- Chinese meetings are structured dialogues between principals on both sides; others participate in the conversation only upon explicit invitation. The Chinese prefer to react to others’ idea, and not to bear the onus of setting the scope of the discussion themselves.

- Chinese often signal the speaker with nods or interjections that they understand what he or she is saying. Such ejaculations do not necessarily signal agreement.

- Don’t interrupt a speaker.

- A good interpreter can help you immeasurably in China. When talking through an interpreter, pause frequently and avoid slang and colloquialisms. Always talk to the host, never directly to the translator.

- Restate what was accomplished at the close of a meeting to guard against misunderstanding. Ask for a contact person for future dealings.

In: Chinese Business Etiquette, 1999, p. 107

Often, intercultural communication exists concerning the practice of listening. Numerous tips about establishing culturally sensitive verbal and written communication practices within an organization exist. While the prevailing norms of communication in American business may call for the listener to be silent and offer body language intended to convince the speaker that his or her words are being taken into account. Many cultures have different standards that may strike the uninitiated as rude or disorienting.

“A person who communicates by leaning forward and getting close may be very threatening to someone who values personal space. And that person could be perceived as hostile and unfriendly, simply because of poor eye contact.” (Monson in: Hillstrom, in web)

In any cross-cultural exchange between managers from different regions, the principal purpose of communication is to seek common ground – to exchange ideas, information, gain customers, and sometimes even establish partnerships between the parties. Business in general and management in particular rely on people’s willingness and ability to convey the meaning between managers, employees, partners, suppliers, investors and customers. There are numerous comprehensive models that attempt to capture the various elements of the communication process.

Fig. 6.2: Cultural influences on the communication process – a model

Source: Adapted from Nardon/Sanchez-Runde/Steers, 2010, p. 202

According to this model (Fig. 6.2), characteristics inherent in the cultural environments of each participant help to determine various beliefs underlying the communication process. In a cross-cultural environment, these cultural drivers often influence the extent to which communication would be open and frank.

As a result of these normative beliefs, certain culturally compatible communication strategies emerge, including people’s expectations and objectives in initiating or responding to a message or comment, choice of language and transmission strategies. Three principal communication behaviors can be identified as verbal, non-verbal and virtual. These strategies are aimed at achieving a number of intended message outcomes.

Limitations on both message content and the choice of message transmission can be found across cultures. This is mostly a challenge for the senders as well as the recipients of the message. Senders must decide how to formulate a message, so it is consistent with the sender’s culture but also consistent with the recipient’s culture. However, what is acceptable in one culture might not necessarily be acceptable in another. Communication patterns include message content, message context, communication protocols, single-language communication, technology-mediated communication, and information-sharing patterns. These all patterns illustrate many of the challenges faced by global managers when communicating across cultures. (Nardon/Sanchez-Runde/Steers, 2010, p. 203)

Tab. 6.1: Selected elements of the negotiation process in comparison between US-Americans, Japanese and Arabs

Source: Based on Chaney/Martin, 1995, p. 183

6.4 Levels of communication

According to Watzlawick et al. (1969) every message has a content aspect and a relationship aspect. Therefore, in our way of communicating with another person we also show our opinion about this person and in which relationship we are in. Hence, the aspect of content transmits information, facts, results etc. and the relationship aspect makes statements about the contact, climate, emotional aspects and the interpersonal relationship.

Relationship aspects are especially transmitted by non-verbal communication. With laughs, intonation, mimic and gestures the speaker expresses for instance what he thinks about the receiver of the message and how important conversation is for him/her. This makes it clear that non-verbal language is often the source of misunderstandings during intercultural meetings (Blom/Meier, 2002, pp.79–80). The interpretation of non-verbal behavior according to own cultural norms, although the conversational partner has his/her own encoding, leads to misunderstandings (ibid.). To understand intercultural communication requires an accurate perception of what is conveyed in the verbal as well as the para- and non-verbal mode. Regarding to that, Jacob (2003, p. 72) states that

“beliefs and attitudes about a person from another culture can often be communicated through behavior, even when nothiing has been verbalized.”

In the following figure, the modes of communication – verbal-, para-verbal-, and non-verbal – are illustrated.

“A journeey of a thousand miles

must begin with a single step.”

(Lao Tzu)

6.5 Verbal communication

6.5.1 Language

Language and culture are strongly interrelated. Language is a symbolic system which consists of features and rules detectable in any human tongue. It is shared by people within a culture. The verbal language is the vehicle for social interaction and empowers to express and create experience. It is necessary for the social mutual collaboration and enables to reveal thoughts.

Frequently used phrases and their meaning in Vietnam

(Elston/Hong Hoa)

- “Eat porridge, then kick the bowl”, describes a person who receives a favour and fails to express gratitude.

- “The young bamboo is easy to bend”, compares bamboo to people. We must teach our children good morals and manners while they are young, because when they get older, like bamboo, become too thick to bend.

- “Catch fish with both hands” is used to describe a person who has a choice between two things and tries to capture both of them in a frantic way instead of concentrating on just one thing at the time.

- “Near the ink is black, near the light is bright”. This one instructs us that if we make bad friends, we will also become bad. The flip side: if we keep good friends, we also become good people.

- “Same the fruit, know the tree”. In this sentence, the fruit is a child, the tree is the father. In English (German), we say something similar, “The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree”.

- “If you don’t venture into the cave, how will you catch the tiger?” tells us that we must risk something in order to gain something.

- “Close the doors, then teach each other” refers to the family circle. When there is a dispute inside the family, we should close the doors and solve the problems privately without involving our neighbors or outsiders“.

- “Far faces, distant hearts” is what happens in a long-distance relationship between two lovers. In English (German), our expression might be “Out of sight, out of mind”.

In: Vietnamese Sayings, in: Destination Vietnam, July/August, San Francisico 1997

6.5.2 Distinctive language features

Language indicates and graduates phenomena like experiences, feeling, ideas, objects, groups, people and many other. There are a lot of differences, but also many similarities in the world-wide language varieties. All of them have the four distinctive features of: arbitrariness, abstractness, meaning-centeredness and creativity.

“Language is viewed as an arbitrary symbolic system” (Chung/Ting-Toomey, 2012, p. 112).

The words are formed with letters, which depend on the graphic representation, and the sound of the word is formed with sound units, which depend on the phonemic. Consequently, words and sounds of each culture have no inherent meaning to the phenomena the word is trying to describe.

In general the meaning of words emerges

“from the specific conventions and expectations shared by members of a given speech community, conventions and expectations that can and do change dramatically from time to time and place to place” (Allen/Jensen, 1995, p. 35).

Language can be used abstractly or for hypothetical thinking. The language abstraction is the process of moving away from concrete and external phenomena. Because of different ethical and moral beliefs, the expression of abstract thoughts, feelings or ideas can differ between cultures, which can cause discomfort and uncertainty. In order to avoid this, it is better to use less abstract and more concrete words, when talking to people from another culture. (Chung/Ting-Toomey, 2012, p. 113)

How to start a conversation iu China

(Scott D. Seligman)

Initial encounters with the Chinese often follow strikingly similar patterns. The following “top ten” questions can help you to build up a conversation:

- Where are you from?

- How long have you been in China?

- Have you visited China before?

- Do you speak Chinese?

- What do you think of China?

- What kind of work do you do?

- Which places in China have you visited?

- Are you accustomed to Chinese food?

- Are you married?

- Do you have children?

In: Chinese Business Etiquette, 1999, p. 26

Although it is possible to label phenomena like situations or feelings with language, the use of second meanings like metaphors are very helpful, because they can express our thinking. George Lakoff, a cognitive scientist and linguist, proposes, that metaphors are

“a major and indispensable part of our ordinary conventional way of conceptualizing the world, and that our everyday behavior reflects our metaphorical understanding of experience” (Martin/Nakayama, 2010, p. 226).

Meaning-centeredness describes the two different, the denotative and connotative, meanings.

“The denotative meaning of a word emphasizes its objective, dictionary definition shared and recognized by the majority members of a linguistic community.

The connotative meaning, on the other hand, stresses the subjective, interpretive meanings of a word constructed by individual members based on their cultural and personalized language experience.” (Chung/Ting-Toomey, 2012, p. 112)

An example for the two different meanings is the word “hook up”. The denotative meaning is “an arrangement of mechanical parts” and the connotative meaning can be interpreted as a casual sexual encounter or dealing drugs.

Within intercultural communication it is necessary to get familiar with metaphors and other connotative meanings to avoid confusion and anxiety.

Creativity

Creativity as a distinctive feature of language consists of three parts: productivity, displacement and meta-communication.

The productivity is the creative capacity to understand the complex structure of a language and vocalize and understand sentences never heard before. The displacement element is the capacity to talk about different time and space, because of the possibility to pass memories end experiences over generations. The meta-communication is the opportunity to use language for cooperative work and communal life. (Chung/Ting-Toomey, 2012, p. 114)

The “fourth” floor

When a group of British people attends a meeting on the “fourth” floor of a London business tower, they know it actually refers to the fifth floor of the building, since Brits distinguish between the ground floor and the first floor. On the other hand, communicating across cultures can be challenging, since the link between words and their meaning is not always clear. When a group of Americans attends a meeting on the “fourth” floor of a New York high-rise, they do, in fact, go to the fourth floor. However, when foreign travelers attend a meeting on the “fourth” floor of a Seoul high-rise, even the more experienced travelers can become puzzled. While the number four (“sa” in Korean) is not unlucky itself, it is pronounced like the Korean word for death. As a result, many Korean buildings either use the English letter “F” for this unnamed floor or simply do not have such floors.

Based on: Nardon/Sanchez-Runde/Steers, 2010

6.5.3 Translation problems

Even within one language and/or culture, translation problems can occur, e.g. when a metaphor is unknown or someone is sarcastic or misunderstood as being sarcastic.

Five problems that can lead to intercultural communication barriers are described here:

Tab. 6.2: Five possible translation problems

| Vocabulary equivalence | “Languages that are different often lack words that are directly translatable.” (Jandt, 2013, pp. 141f ) |

| Idiomatic equivalence | “In translating idioms, the translator meets various difficulties that are not so easy to overcome. The main problem is the lack of equivalence on the idiom level. It would be perfect if a translator could find an idiom in the target language which was the same in its form and meaning as that of the source language. However, even though each language has its idioms, it is still hard to find the exact equivalent.” (Straksiené, 2013, p. 1) |

| Grammatical-syntactical equivalence | “That simply means that languages don’t necessarily have the same grammar.” (Jandt, 2013, p. 143) |

| Experiential equivalence | “If an object or experience does not exist in your culture, it’s difficult to translate words referring to that object or experience into that language when no words may exist for them.” (ibid.) |

| Conceptual equivalence | “The problem of conceptual equivalence refers to abstract ideas that may not exist in the same fashion in different languages.” (ibid., pp. 143f) |

| Vocabulary equivalence | “Languages that are different often lack words that are directly translatable.” (ibid., pp. 141f) |

6.5.4 English as a lingua franca

In the whole world, the use of English has become more common and essential. In order to be able to communicate in the wide range of international business, English is set as the common communication language. While in the 19th century, English was the language of commerce, French of diplomacy and German of science, today English is the universal language of all three of them, although it is not the world-wide most widely spoken language, as you can see in the following figure. (Jandt, 2013, pp. 147f)

Through colonialism and emigrations the English language spread over to other continents and counted by 1990 an estimated number of 750 million people using English as their second language. Today English dominates areas like science, technology, commerce, tourism, diplomacy and music. It is the native language in 12 countries and 33 others use it as official or semiofficial language. The study of English is mandatory or admired in at least 56 countries. Through global communication English has become necessary for companies, scientists and politicians. (Jandt, 2013, pp. 148f.; Rothlauf, 2012, pp. 202f)

Tab. 6.3: The five most widely spoken languages worldwide

Source: Ethnologue.com, 2014

| Language | Approximate number of speakers |

|---|---|

| 1. Chinese | 1,197,000,000 |

| (Mandarin) | (848,000,000) |

| 2. Spanish | 414,000,000 |

| 3. English | 335,000,000 |

| 4. Hindi | 260,000,000 |

| 5. Arabic | 237,000,000 |

6.5.5 Direct and indirect styles of verbal communication

The shape of a message can differ even when the purpose is the same. The differences are often the tone of voice and the immediacy of the content. The direct styles distinctly unveil the speakers’ intentions with a notable tone of voice, while the indirect styles camouflage the speakers’ aim with a calm voice. Of course these styles are mixed up in many different forms, however the direct is commonly used in individualistic, and the indirect style is frequently used in collectivistic cultures. (Chung/Ting-Toomey, 2012, p. 125)

The difference of these styles is most obvious in a request situation. A direct style user just asks for a request giving the information about what he needs. An indirect style user would not ask that straightforwardly, but would give background information expecting that the listener or interpreter can infer what he or she needs. While the direct style user wants to get a clear “yes” or “no”, the indirect style user would never get him-/herself caught in a situation where the listener has to say “no”, because this would mean that both of them lose their face. (ibid, pp. 125f)

When a direct and an indirect style user meet in a business environment, a misunderstanding or even a conflict situation is inevitable and no result will be reached. Therefore it is necessary for intercultural businessmen to analyze the cultural background of their negotiation partner to prevent misunderstandings and to achieve a goal.

“Warming-up” phase in China

“It’s important, not to come in swinging, but to establish the foundation of a relationship and build slowly. There is no need to rush into a discussion of business; the topic will come up naturally in time. Most Chinese gatherings begin with small talk, especially when the host and guests do not know one another well.”

(Seligman, 1999, p. 95)

“Business meetings typically start with pleasantries such as tea and general conversation about the guests’ trip to the country, local accommodations, and family. In most cases, the host already has been briefed on the background of the visitor.”

(Harris/Moran, 1991, p. 410)

6.5.6 Written communication

The written word can have a huge impact. It is even more influential than the spoken word, because it can be read over and over again. William Howard Taft, the 27th president of the USA, once said:

“Don’t write so that you can be understood, write so that you can’t be misunderstood.”

Written communication in general

Written communication means that the writer is usually distant from the reader. Therefore, the written word is mostly very different from the spoken word. In order to understand the message it is necessary to leave out any ambiguity in writing. In the written communication, there are no additional linguistic features, such as eye-contact or other nonverbal behavior. When writing a message, the context has to be clear and understandable for the receiver. (Indrová, 2011, pp. 7f)

Written communication in business

It’s not possible to imagine business without written communication, because it has so many usable features. Because of its durable nature, important facts can be recorded to re-read or to analyze at any time. It can show some information in a more detailed, logical or effective way, e.g. through graphs or tables, messages can be distributed faster to a bigger group of people. (ibid.)

To effectuate written communication in business some rules should be followed:

- Make sure your spelling and use of grammar is correct.

- Keep your message short to make sure it will soon be read and easily understood.

- Pay attention to the “subject” and the first sentence of your message. The attention of the receiver must be raised and he/she should also be able to quickly grasp your intention.

- Try to avoid negative verbalizations but rather formulate your message positively.

- Keep in contact with business partners, e.g. by sending – congratulatory notes or thank-you-emails etc.

- Always double-check your message before sending it off.

Forms of Address: Chinese Names

(Scott D. Seligman)

The first thing you need to remember about Chinese names is that the surname comes first, not last. More than 95 percent of all Chinese surnames are one syllable – that is to say, one character – in length; some of the most common examples are Wang, Chen, Zhang, Li, Zhao, and Lin.

For business purposes it is traditionally acceptable to call a Chinese person by the surname, together with a title such as Mister or Miss or even Minister or Managing Director. Thus Mr. Wang, Managing Director Liu, or Ms. Zhao would all be acceptable forms of address, and there is no problem with mixing an English title and a Chinese surname in just that order.

In: Chinese Business Etiquette, New York, 1999, p. 32

6.5.7 Listening skills

Winston Churchill once said:

“Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak. Courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen.”

Every effective speaker should have an effective listener. Being a good listener means he or she (Arent, 2009, p. 8):

- “stays focused on the speaker’s main point (more global than discrete)

- tunes out all potential distractions (or ask for time to remove them)

- offers the fullest possible attention (manages any emotional reaction, especially if a particular word or phrase is used.)

- gives signals that he or she is listening as objectively as possible (use eye contact or other nonverbal cues, or fillers, such as yeah, uh huh, ok, I know what you mean, or equivalent expressions in another language)

- is flexible and open-minded when new topics or ideas are raised (these concepts are cultural specific in practice, but the general point remains that these traits have a positive impact on overall listening effectiveness)

- asks for clarification if anything is unclear (how that is done will depend on the language and culture involved; all languages have a way to ask questions and make clarification requests)

- validates the speaker’s main points (conveying that they are received, considered and under review, such validation may be verbal, non-verbal or both).”

The factors mentioned are depending on the culture of the country.

6.6 Paraverbal communication

One of the most important elements in intercultural communication is paraverbal communication. It encompasses the instrument of the voice and consists of the loudness of our voice, the speech melody, the speaking tempo, the pitch of our voice and the emphasis of different words in a sentence. (Mruk-Badiane, 2007, p. 4)

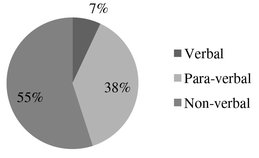

Those things are different from culture to culture, which makes it more complicated to understand the message of people from other counties and cultures correctly. It is important to know how to use the voice efficiently to reach certain goals, either in private conversations or in business negotiation. Around about 38 % of our messages are made up by paraverbal communication (see Fig. 6.4).

A paraverbal message and its interpretation

(Jürgen Rothlauf)

A sentence can have entirely different meanings depending on intonation and emphasis. Six different conclusions are possible as far as the following statement is concerned:

“I didn’t say you were impolite.”

“I DIDN’T say you were impolite.”

“I didn’t SAY you were impolite.”

“I didn’t say YOU were impolite.”

“I didn’t say you WERE impolite.”

“I didn’t say you were IMPOLITE.”

In: Seminarunterlagen, 2013, p. 14

6.6.1 Communicating to display emotion

Showing emotion in nonverbal and verbal communication varies between high-context and low-context cultures. In China, Japan, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and other collectivist Asian countries, culture socializes people from an early age not to show emotion publicly. No doubt, this is because a display of emotion could have potential consequences of disrupting the harmony that is so important to collectivist cultures. In Iraq, Dubai, Jordan, Kuwait, and other collectivist Middle Eastern countries, culture teaches people from an early age to show emotion and how to do it (Varner/Beamer, 2011, p. 159).

Obviously, the level of emotion shown can have consequences in work environments, where people from emotion-expressive cultures interact with people from emotion-repressive cultures. When someone from an emotion-expressive culture – say Polish – “performs” a communication transaction about a perceived mistake with someone from an emotion-repressive culture – say Thai – both could be sending messages the other has trouble decoding correctly because of the different communication styles. The Pole may be perceived to be immature, out of control, and egocentric. The Thai might be perceived to be remote, unsympathetic, and uptight. These perceptions then form the context for the worded message, which is subject to distortion and misinterpretation, or in other words, faulty decoding.

Egyptians display socially acceptable emotion. The emotion of anger is not socially acceptable, but not to show emotion in the face of another person’s grief, jubilation, or disappointment is regarded as self-centered and egoistic. To be impassive can result in a denied group membership.

6.6.2 Effect of speaking

Silence

(Hayashi Shujl)

A Japanese company and a German firm were considering a tie-up. Preliminary discussions were promising, and negotiating teams from each corporation met to hammer out a basic agreement. Throughout the meeting the senior Japanese Representative sat straight in his seat, said nothing and often closed his eyes. Angered by his apparent aloof indifference, the German team finally broke off the talks.” […] If they had understood local customs better, the negotiations would not have collapsed.

The speaking tempo includes the sound and syllable lengths of the words, and pauses. The lengths of the pauses differ in every country and culture and can be interpreted in a wrong way if people have no information about them.

In general, there are two different types of pauses, “filled pauses” and “unfilled pauses”. “Filled pauses” consist of words, are stuffed with words like “then” and “well” and are used for thinking about how to go on in a sentence without saying anything. “Unfilled pauses” are pauses in which nobody says something, there is absolute silence. The amount of seconds with absolute silence differentiates from culture to culture. (Gebhard, 2012, pp. 39ff) In negotiation and business meetings, pauses can be used to reach a certain effect or to support the meaning of a sentence and let the other team member or partner think about the words. In the culture of China it is usual to use pauses in speaking to show the guest who of them is the leader of this conversation. Especially Chinese team leaders use longer pauses for making clear which team member is the leader with the highest position. (Berkemeier/Scholz, 2006, p. 6)

Sharing

Four Russian friends meet. One has a chocolate bar. He pulls out his pocket knife and carefully cuts the chocolate into four minuscule but equal pieces and divides it among the four. In other countries, four friends would not typically think of equally distributing such a small portion. “If I want one, I will buy my own” would perhaps be the attitude. In Russia, the sharing of food or consumables is of primary importance.

In: Russian Etiquette & Ethics in Business, Chicago, 1996, p. 71

For Japan, Kaminura describes this kind of communication as follows (1995, p. 670):

“The person who is self-confident but very humble in attitudes is rather respected in Japan. We do not use direct expressions, but a listener should read and understand between the lines to get a message. As a result, I think that Japanese are passive in their general attitude whereas Westerners are aggressive based on individual mind.”

6.7 Nonverbal communication

Nonverbal messages can be broken down into subcategories. Although this makes the discussion easier, one has to be careful not to assume that speakers use nonverbal signals in isolation. In most cases, speakers use many different signals at the same time. We may move our hands, nod with our heads, smile, and keep close eye contact, all at the same time. The non-verbal messages that give listeners the most trouble are those with accompany words. It’s the tone of voice, the look on someone’s face, or the lack of eye contact that makes you wonder if you are understood.

Most people still believe that the main part of communication is the verbal part, which includes the written part. However, it is not. The verbal part accounts for only 7 % of the communication. The other 38 % include the tone of voice, in other words the paraverbal part and the biggest part is the nonverbal part, which covers 55 % of the overall communication.

6.7.1 Six categories of nonverbal communication

Nonverbal or nonworded communication includes all communication beyond the spoken or written word. Gesteland (2002, p. 73–78) has defined six categories that can help to get a better understanding of the complexity of nonverbal communication.

Proxemics – the study of space

“Proxemics is the branch of knowledge that deals with the amount of space that people feel it necessary to set between themselves and others.” (Oxford Dictionaries)

In the early 1960s, the term “proxemics” – originating from “proximity” or nearness – was introduced by the American anthropologist Edward Hall (Pease/Pease, 2004, p. 192). Many people never think about how much space should be between us. We do it intuitively. During our childhood, we develop a feeling for our own “space bubble” (Gesteland, 2002, p. 72.), because we recognize it from our parents, friends and other members of our culture. Indeed it is not inborn, but we learn it by observation. (Beamer/Varner, 2011, p. 234)

The closet zone is the intimate space. Only those people who are familiar to us such as family, close friends or animals are allowed to be in this zone. The personal space is used for interactions between colleagues, acquaintances or people we meet at social parties. The next zone is the social space which we use for interaction with strangers, such as a new employee at work or a craftsman repairing things at your own house. The public space is the zone which we use when we meet people in a large group. (Pease/Pease, 2004, p. 192)

People from one culture can easily interact with each other without disturbing their personal space. Nevertheless in business it is important nowadays to interact within different cultures. The use of space differs a lot from culture to culture which means people from the Mediterranean Region can stand very close to each other. However, if a person from the Mediterranean Region stands next to a person from the United States, such as they would do it intuitively, the person from the United States (distant culture) would step back because it is too close and it is not anymore in the personal zone. In other words, the person does not feel comfortable anymore. Close and distant cultures are displayed in the following table.

Tab. 6.4: Distance behavior: The use of space

Source: Gesteland, 2002, p. 73

| CLOSE: | DISTANT: |

|---|---|

| 20–35 cm (8-14 inches) | 40-60 cm (16-24 inches) |

| The Arab World | Most Asians |

| The Mediterranean Region | Northern, Central and Eastern Europeans |

| Latin Europe | North Americans |

“Haptic is related to the sense of touch.” (Oxford Dictionaries)

Holding or shaking hands, kissing cheeks and also brushing arms belong to this kind of non-verbal communication.

In every culture, there is a different association towards touching. People from a high contact culture, such as the Mediterranean Region, feel comfortable with touching one another, e.g. kissing the cheek or hugging when one has just met. In other cultures, such as North America, it is uncommon to touch people one has just met. People would say “Hello” to one another and maybe wave their hands as a greeting sign. When people of this culture know each other better, they like to hug one another as greeting. The third kind of classification is the low contact. Those cultures, for example in the United Kingdom, do not like to touch in public at all, neither good friends nor family members. (Gesteland, 2002, p. 74) This association of the cultures towards touching is comparable to the distant zones of the cultures. The bigger the distant zone of one culture, the less people from this culture like to touch and vice versa.

In Asian countries, people do not shake hands. They usually bow as a greeting sign in Japan. The bow starts from the hip with a straight back and the neck also remains straight. Men hold their hands at the side, but the women put their hands on their legs. In other countries, such as Argentina, it is common for men and women to touch the women’s right cheek. In Lebanon, men give three cheek kisses to other men, first on the right side, then on the left side and again on the right side. (Beamer/Varner, 2011, pp. 231f) In India, it is also possible that a man takes the other hand of a man when walking side by side. It is only a sign of friendship and is not connected to homosexuality. (Gesteland, 2002, p. 75)

Nevertheless, in many cultures, the handshake has become the most common form of greeting in formal business situations, which was first used when closing a commercial transaction in the nineteenth century. It is “a sign of trust and welcome” to the other person. (Pease/Pease, 2004, p. 41) This greeting ritual differs from region to region. While some cultures shake hands softly and long, other cultures do it distinctly and quickly.

The biggest problem is the way of exchanging handshakes. People from other cultures may wonder why the handshake feels too soft or too strong, or in some cases the other person might not have been allowed to reach for the counterpart’s hand first. The result might be an uncomfortable situation. Germans and French people like to pump very briefly, only one to two times. In the United Kingdom, they give a pump of three to five times and the Americans like to pump even five to seven times. It might happen that the short-shaker can seem as restrained for the long-shaker. (Pease/Pease, 2004, p. 114)

In some circumstances it can happen that a woman has to wait until she gets the other men’s hand reached for handshaking, such as in Czech Republic. (Gesteland, 2002, p. 323) Another example, in Mexico it is also possible that a woman has to extend her hand first after the man gave a slight bow, or in some other countries while the people shake hands they put their free hands on the forearm of the other person, such as in the Arab World. (Gesteland, 2002, p. 222; Beamer/Varner, 2011, p. 231) Moreover, good eye contact while shaking hands is important in other countries, such as Germany, Spain and Canada. (Gesteland, 2002, pp. 261, 313, 335)

Kinesics – the study of movement

Kinesics is “the study of the way in which certain body movements and gestures regarded as a form of non-verbal communication” (Oxford Dictionary).

Facial expressions

Every human likes to smile and to laugh. However, there can be differences in meaning: smiling and laughing can stand for happiness, joy and also for embarrassment. For example people from the United States like to smile and laugh as often as they can. They do not try to hide any feelings. Indeed, Japanese people also smile, but they usually do not try to show it in public. The German culture also seems to be cautious with smiling. The difference to the East Asian culture is that the German do not try to hide any feelings. They just do not want to smile or to laugh because most of them are very serious. The opposite are the Arab and Latin countries. They like to smile and laugh, and they also use their hands and arms to show their emotions. (Beamer/Varner, 2011, p. 224)

Frowning is another important form of facial expressions. In their own culture can the meaning of that frowning easily be identified, but in a different cultures can it be differently interpreted. For example in North America mean raised eyebrows interest and surprise. British are skeptic and Chinese people disagree when they raise their eyebrows. Filipinos like to say “Hello!” with this gesture and for Arabs is it a sign for “No!”. For doing business in a different culture, it is important to be careful with one’s own facial expressions, because they might even mean the opposite. (Gesteland, 2002, p. 79)

Head gestures

Everybody around the world nods. Nodding can be a form of agreement, disagreement and listening. In most cultures, moving the head up and down means that you agree with someone. And shaking your head from side to side means that you disagree. One exception is Bulgaria. Bulgarians agree with shaking their heads from one side to the other and disagree with moving the head up and down. Moreover, moving the head up and down might in some cultures only mean that the person listens and understands what has been said but does not necessarily mean that the person actually also agrees. (Beamer/Varner, 2011, p. 226)

Arm movements and gestures

In Latin cultures and also the Arab World, they like to internsively use their arms and hands to show their emotions and to underline what they are saying. It is possible that the other person is touched while a person from those cultures talks. This would disturbe e.g. a Japanese person. They usually do not use their hands and arms to underline their message, because they do not want to get into another person’s space zone, which is very large in Japan in contrast to Latin and Arab cultures. Those cultures have problems to interpret the other’s gestures, because using the arms and hands means in the Arab World that you are interested in the conversation while in Japan it means that you destroy the harmony of the group. (Beamer/Varner, 2011, pp. 226f)

To hand over things, such as papers or business cards, it is important to know how hand them over correctly. For example in Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist countries, you should not use your left hand for giving papers or business cards to another person or even to shake left hands with somebody. The left hand is used for cleaning rituals. Therefore, always use your right hand there (Gesteland, 2002, p. 79). We will take a closer look at business cards later in this chapter.

Gestures in China

- Avoid making exaggerated gestures or using dramatic facial expressions. The Chinese do not use their hands when speaking, and become distracted by a speaker who does.

- The Chinese do not like to be touched by people they do not know. This is especially important to remember when dealing with older people or people in important positions.

- Use an open hand rather than one finger to point.

- To beckon, turn the palm down and wave the fingers toward the body.

In: Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands: how to do business in sixty countries, Massachusetts, 1994, p. 61

Posture

According to Oxford Dictionaries, posture can be defined in two ways:

- It can be “a particular position of the body”, “in which someone holds their body when standing or sitting.”

- It can be “a particular approach or attitude”, which is “a way of behaving that is intended to convey a false impression (a pose)”.

In international business is it important to know how to do it correctly. To stand upright with shoulder back and a high held head is a good way to show self-confidence. Everybody can read this posture around the world. However, there are differences as far as the right sitting position is concerned. Some companies in Japan are not westernized and the people are supposed to sit cross-legged on the floor. In other cultures where women are really new in business, they should not cross their legs at the knee. It is better when they put their legs together and do not occupy too much space. (Beamer/Varner, 2011, p. 228)

Oculesics – the study of eye behavior

Oculesics is another form of the nonverbal language.

“Several oculesics behaviors, including eye contact, gaze and pupil dilation, can convey immediacy in interpersonal communication.” (Manusov, 2009, p. 12)

The eye gaze is a not only a sign of respect for the own culture. It is also a very important part in cross-cultural business. When Arabian and Japanese people meet, uncomfortable situations can often be expected. Both sides misunderstand the repective gaze by interpreting with the help of their own cultural understanding. For the Arabs, it is usually a significant matter to look at somebody’s eyes. They consciously read the feelings and also the truthfulness of the counterpart’s statement. If they cannot see the other person’s eyes clearly, they move closer. Japanese people do not even try to make eye contact. It is disrespectful for them. They like to keep their distance and their privacy, too. In this particular case, when an Arab meets a Japanese person, the Arab would like to come closer and to look in the Japanese person’s eyes, whereas the Japanese would try to look away and probably try to escape this situation. The Japanese person could also try to avoid this situation by wearing sunglasses. Consequently, the Arab will not be able to read the Japanese person’s eyes and will perhaps not try to come closer. Not only when you meet a person in business situations but also in public, you should try to avoid eye contact in Asian countries. When you pass people just look at the ground or look past them. Otherwise, it would be considered as impolite. In other countries, such as the Mediterranean Region and Latin America, do not try to look away. It is often a sign that a person has something to hide or even does not like the other person. For “Westernized” women, it could also be interpreted as a sign of sexual harassment, but it is a cultural norm in those countries and should not be misinterpreted. (Beamer/Varner, 2011, pp. 221ff)

Olfactics – the study of scent

“The study of communication via smell is called Olfactics. In all cultures, women can detect odors in lower concentrations, identify them more accurately and remember them longer than men.” (Doty et al., 1984)

In business as well as in private life, a good first impression can make things easier. As far as the interpretation of body odor and perfume is concerned, every culture has a different approach. For example in the Western culture, the usage of deodorant and perfume is a must. People of this culture do not like any natural body smell, because it is a sign of untidiness. The culture of the Arab World regards the natural body odors as usual and does not mind if another person smells. For Asian cultures, the smell of body odor is a criticalpoint. They use at least deodorant and often perfume. A person from the Arab World should use deodorant and perfume but not too much, so the person of Asian cultures is not bothered of it. (Jandt, 2013, p. 123)

Chronemics – the study of time

“The study of the communicative function of time.” (“Definitions”, in web)

Traditional cultures regard the time as cyclical. The rhythms of nature and the cosmos dictate this view: Day yields to night, which in turn yields to day again; rain follows dry periods that come after rain; the time to plant leads to the time to nurture, then to the time to harvest and to the time plants die. Everything follows a pattern of birth, life, death and renewal – even daily activities, after which the weary body sleeps and awakes refreshed. Within the cyclical framework, events that occur take as long as they take; their duration is dictated by their essential nature. This view is common among agrarian cultures whose members are closely attuned to the rhythms of cultivation. The corn will be ripe when it has finished ripening, in its own time. It is also persistent in cultures that value human interaction and relationship (Varner/Beamer, 2011, p. 130–131).

What does it mean to be “on time”? The definition of punctuality varies from culture to culture. The cultural priority of time has close links to another priority: relationship versus results. When people are important and the nurturing of relationship matters, the time necessary for those activities is flexible.

You might have an appointment in Jeddah/Saudi Arabia at 10 a.m. and you might be the second appointment on the person’s agenda, and you might still be waiting at 11 a.m. Everybody is so important that no meeting can be rushed for the sake of a schedule that is imposed arbitrarily. In Buenos Aires/Argentina, traffic snarls often delay people from arriving on time at meetings, and although an apology is expected, lateness is not considered an insult. Both Saudi Arabians and Argentinians have strong orientations towards building relationships in order to do business effectively.

In results-oriented cultures, adherence to schedules is much more important. In Israel, for example, promptness is a basic courtesy as well as an indication of seriousness about work. In Russia, time is not related to cost or profits, and punctuality – being “on time” – is an alien concept:

“Russians are notoriously not on time, and they think nothing of arriving long after the appointed hour, which is not considered as being late” (Richmond, 1992, p. 122).

As shown in chapter 2, Hall differentiated between monochronic (one-dimensional) time and polychronic (multidimensional) time. Monochronic time is linear and people are expected to arrive at work on time and work for a certain number of hours at certain activities. In polychronic cultures, time is an open-ended resource that is not to be constrained. Context sets the pace and rhythm, not the clock. Events take as long as they need to take; communication does not have to conclude according to the clock. Different activities have different clocks.

6.7.2 Dress code

Businesspeople must be particularly sensitive to dress in other cultures because of the negative image tourists have created. Westerners often assume that their leisure dress is appropriated everywhere. The standard business dress around the world is the suit, shirt, and tie for men, and some sort of suit or dress for women. That sounds easy, yet there are enough variations indicating authority that businesspeople must be aware of local customs and tradition. Some examples how to dress correctly are to be found in the following box.

Dress Code around the world – some examples

- Dress is very important for making a good impression. Your entire wardrobe will be scrutinized.

- While Argentines are more in touch with European clothing styles than many Latin Americans, they tend towards the modest and the subdued. The provocative clothing in Brazil, for example, is rarely seen in Argentina.

- Business dress is fairly conservative: dark suits and ties for men; white blouses and dark skirts for women.

- Both men and women wear pants as casual wear. If you are meeting business associates (outdoor barbecues, called asado, are popular), avoid jeans and wear a jacket or blazer. Women should not wear shorts, except when invited to a swimming pool.

- For business, men should wear conservative suits, shirts, and ties. Loud colors are not appropriate. Women should also wear conservative suits, with high-necked blouses, and low heels – their colors should be as neutral as possible.

- At formal occasions, no high heels or evening gowns are necessary for women unless the event is a formal reception given by a foreign diplomat. Men may wear suits and ties.

- The French are very aware of the dress. Be conservative and invest in well-made clothes and shoes.

- Men should wear dark suits and the women should also wear conservative suits.

- For business dress, men should wear a suit and tie, although the jacket may be removed in the summer. Businesswomen should wear conservative dresses or pantsuits.

- For casual wear, short-sleeved shirts and long trousers are preferred for men. Women must keep their upper arms, chest, back, and legs covered at all times.

- Note that wearing leather (including belts, handbags, or purses) may be considered offensive, especially in temples. Hindus revere cows, and do not use leather products.

Saudi Arabia:

- Foreigners should wear Western clothes that approach the modesty of Saudi dress. Despite the heat of the desert, most of the body must remain covered.

- Men should wear long trousers and a shirt, preferably long-sleeved. A jacket and tie are usually required for business meetings. Keep shirts buttoned up to the collarbone. Saudi law prohibits the wearing of neck jewelry by men, and Westerners have been arrested for violating such rules.

- Women must wear modest clothing. The neckline should be high, and the sleeves should come to at least the elbows. Hemlines should be well below the knee, if not ankle-length. The overall effect should be one of baggy concealment; a full-length outfit that is tight and revealing is not acceptable. Therefore, pants or pantsuits are not recommended. While a hat or scarf is not always required, it is wise to keep a scarf at hand.

The overall message is clear: you have to show respect and sincerity by the way you dress and by respecting certain rules of appearance of the host culture. That does not mean you have to adopt your clothes to the customs of the host culture. Keep in mind that you are a representative of your country and the way you are dressed is based upon your own point of view as a business man or a business woman.

6.7.3 Business cards

To communicate well and build successful relationships with people from around the world, the right handling of business cards is part of any intercultural competence. One of the first official acts in being involved in international business is the exchange of business cards. Business cards have an important function.

Forms of Address: Chinese Names

(Scott D. Seligman)

The first thing you need to remember about Chinese names is that the surname comes first, not last. More than 95 percent of all Chinese surnames are one syllable – that is to say, one character – in length; some of the most common examples are Wang, Chen, Zhang, Li, Zhao, and Lin. For business purposes it is traditionally acceptable to call a Chinese person by the surname, together with a title such as Mister or Miss or even Minister or Managing Director. Thus Mr. Wang, Managing Director Liu, or Ms. Zhao would all be acceptable forms of address, and there is no problem with mixing an English title and a Chinese surname in just that order.

In: Chinese Business Etiquette, New York, 1999, p. 32

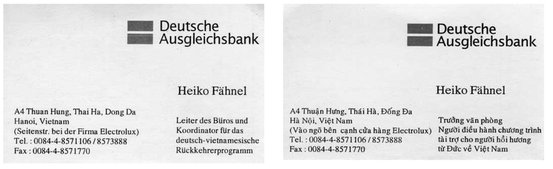

This can be best demonstrated by the example of Japan. Like other countries of the world, Japan has its own business customs and culture. If someone fails to adhere to these traditions, the individual runs the risk of being perceived as ineffective or uncaring. The exchange of business cards is an integral part of Japanese business etiquette, and Japanese businesspeople exchange these cards when meeting someone for the first time. Additionally, those who are most likely to interface with non-Japanese are supplied with business cards printed in Japanese on one side and a foreign language, usually English, on the reverse side. This is aimed at enhancing recognition and pronunciation of Japanese names, which are often unfamiliar to foreign businesspeople. Conversely, it is advisable for foreign business people to carry and exchange with their Japanese counterparts a similar type of card printed in Japanese and in their native language. These cards can often be obtained through business centers in major hotels. Of course, this also applies to other countries and an example of a bilingual business card from Vietnam can be found in the following.

Vietnames names and forms of address

The full Vietnamese name is usually composed of two or three parts. In contrast to the European tradition, the surname comes first. As a middle name, “Thi” for a girl and “Van” for a boy are often used. For the actual first name, a careful selection takes place, since it is common belief that especially the first name will influence the person’s life. Girls are often named after flowers or trees, e.g. Hong (rose) or Lien (lotus), while the boys’ names are often connected to certain characteristiccs, such as smart (Minh) or virtuous (Duc). (HIWC, 1998, p. 9)

When exchanging business cards, one often asks for the other person’s name. This is also done to be able to address the counterpart correctly. If you have seen that the contact’s name is “Dr. Pham Van Pho” and he holds the title “Director”, as you can see in this example, the correct form of address would be “Dr. Pho”. In general, people are addressed with their title and their first name, or only with their title (“Thank you, Director”).

As far as the formal description of the visitor’s current position within a company is concerned, there are some particularities one should keep in mind. As an example, we suppose that you are a Marketing Director in yoour home country and you are allowed to sign contracts. The counterpart in Japan is on the same level and is called Kacho, but without any competence to give you all the necessary information for a final deal. Only for this purpose, one should get promoted, for example to an Executive Managing Director in order to meet somebody who has the relevant information and the support from the top management.

Tab. 6.5: Titles and positions in Japanese companies

Source: JETRO, 1975, p. 9

| Japanese titles | English translation |

|---|---|

| Kaicho | Chairman |

| Shacho | President |

| Fuku Shacho | Vice-President |

| Senmu Torishimariyaku | Senior Executive Managing Director |

| Jomu Torishimariyaku | Executive Managing Director |

| Torishimariyaku | Director |

| Bucho | General Manager |

| Bucho Dairi | Deputy General Manager |

| Kacho | Manager |

| Kacha Dairi | Assistant Manager |

| Kakaricho | Chief |

When receiving a card, it is considered common courtesy to offer one in return. In fact, not returning a card might convey the impression that the manager is not committed to a meaningful business relationship in the future. Business cards should be presented and received with both hands. When presenting one’s card, the presentor’s name should be facing the person who is receiving the card so the receiver can easily read it. When receiving a business card, it should be handled with care and if the receiver is sitting at a conference or other type of table, the card should be placed in front of the individual for the duration of the meeting. It is considered rude to put a prospective business partner’s card in one’s pocket before sitting down to discuss business matters. In order to avoid a certain kind of embarrassment, you should have a sufficient number of business cards at hand, respectively in your hotel.

6.7.4 Gifts

Arab Business Culture

(Jehad Al-Omari)

As business is personal, exchanging favors is very common in the Arab world. There is no stigma or sense of shame attached to the giving and receiving of favors. So you should neither be embarrassed to ask for a favor, nor reluctant to grant one when asked. This is especially true for small favors: for example, arranging to visit your host‘s son who is studying in the West; sending medicine to his sick mother; arranging to meet a friend at the airport. These would be standard favors that would not cost much financially, nor interfere with general moral codes.

In: Simple Guide to the Arab Way: Practical tips on Arab culture, 2003, p. 22

In cultures where business is personal, gift-giving and exchanging favors is a universal way to please someone. However, a lot of misunderstandings can occur in this context if one is not fully aware about the right or wrong doing. The following example may underline what can happen if such a misinterpretation takes place (Martin/Nakayama, 2010, p. 279):

“One colleague of mine, Nishehs, once tried to impress our boss, Joe. Nishehs brought a well-wrapped gift to Joe and he was pleased as he received the gift, but his smile faded away quickly right after he opened the gift. Joe questioned Nishehs angrily, “Why is it green?” Shocked and speechless, Nishehs murmured, “What‘s wrong with a green hat?”

The misunderstanding resulted from the cultural differences between them. Nishehs is an Indian, whereas Joe is Chinese. For the Chinese, a green hat means one’s wife is having an affair.

Gifts in China

(Scott D. Seligman)

Because gift-giving is an area in which common practice departs from the rules, it’s hard to be categorical in giving advice on how best to proceed. The most conservative approach remains the traditional one: a single large gift for the whole group, presented to the leader either during a meeting or a banquet. On the more reckless end of the spectrum would be a very valuable gift presented in private to a powerful individual; the chances of this being construed as bribery if discovered are great.

In: Chinese Business Etiquette, New York, 1999, p. 169

There are a lot of questions that have to be answered:

- Which colors should be avoided and which colors are associated with positive feelings?

- When has the right time come to hand over gifts and to whom first?

- Who starts with the exchange of gifts?

- Which kind of gifts are prohibited?

- What is the role of women in this context?

- Is there a difference between a business and a private invitation?

- What is the right value of a gift?

- Does the body language play a role?

- What about imitation as a gift?

- Is bribery a topic in this context?

People of all cultures like to be surprised with a gift that fits into the given context. Here, your intercultural skills are required. The best intercultural recommendation one can give is to take a look at books that specifically deal with those questions.

The following box will help you to gain such an insight.

Gifts all around the world – some examples

(Morrison/Conaway/B ordon)

- A bottle of wine is a good token of appreciation when you go to a Finnish home (along with the flowers for the hostess).

- Business gifts should not be too extravagant or too skimpy, and should not be given at a first meeting.

- A personalized gift, such as a book on a topic of interest to your client, is appreciated.

- Fiskars scissors (with the orange handles) are the most commonly imitated Finnish product. Avoid giving any type of gift that may compete with them.

- Gift giving is a traditional part of Indonesian culture. Although gifts may be small, they are given often.

- You will give gifts to celebrate an occasion, when you return from a trip, when you are invited to an Indonesian home, when a visitor comes to your office or workplace, and in return for services rendered.

- It is not the custom to unwrap a gift in presence of the giver. To do so would suggest that the recipient is greedy and impatient.

- Since pork and alcohol are prohibited to observing Muslims, do not give them as gifts to Indonesians. Other foods make good gifts, although meat products must be halal (the Muslim equivalent of kosher).

- Muslim Indonesians consider dogs unclean. Do not give toy dogs or gifts with pictures of dogs.

- Avoid giving a gift until you know something about the person you are giving it to. Especially with Orthodox Jews and Arabs, a gift must not violate one of the restrictions of their belief system.

- If you are invited to an Israeli home, bring a gift of flowers or candy. Be sure a gift of food is kosher if it is going to an Orthodox person.

- Make sure you give or receive gifts with the right hand, not with the left (although using both hands is acceptable).

- Giving gifts to executives in a business context is not required. However, small gifts, such as items with a company logo (for an initial visit) or a bottle of wine or scotch (on subsequent trips), are appreciated.

- When giving flowers, be aware that Mexican folklore maintains that yellow flowers represent death, red flowers cast spells, and white flowers lift spells.

- Secretaries do expect gifts. A government secretary who performs any service for you is given a token gift. For secretaries in the private sector, a more valuable (such as perfume or a scarf) should be given on a return visit. A businessman giving such a gift to a female secretary should say that the gift was sent by his wife.

- Avoid giving gifts made of silver; silver is associated with trinkets sold to tourists in Mexico.

- Gifts of knives should be avoided in Latin America, as they can symbolize the severing of friendship.

- Business gifts are discouraged by the law, which allows only a $25 tax deduction on gifts.

- When you visit a home, it is not necessary to take a gift; however, it is always appreciated. You may take flowers, a plant, or a bottle of wine.

- If you wish to give flowers, have them sent ahead so as not to burden your hostess with taking care of them when you arrive.

- If you stay in a U.S. home for a few days, a gift is appropriated. You may also write a letter of thanks.

In: Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands, 1994, p. 33ff

6.8 The expert’s view: Interview with Daniel Frisch

Living and working in South Korea as a German, Daniel Frisch, Head of Business Management APAC for Siemens Ultrasound/Vice President for Sales and Marketing of Ultrasound could provide valuable insights into intercultural communication in Korea.

In: Darmer/Geigle/Persidska/Sikinger, Written Assignement, 2013 (unpublished)

The 16th Annual IMI Conference on Incultural Relations

For more than 50 years, the Intercultural Management Institute (IMI) – formerly the Business Council for International Understanding Institute (BCIU) – has worked toward promoting cultural understanding through innovative and dynamic intercultural communication training. Never before have the effects of international communication been so far-reaching and immediate. The lesson is clear: in our global community, we tend to ignore the importance of intercultural relations at our own peril. Reciprocally, collectively we have made tremendous strides in the field of intercultural relations, and it is those successes and best practices that we continue to share at our annual conference. Join us for the IMI 15th Annual Conference on Intercultural Relations: A Forum for Business, Education and Training Professionals, March 13–14, 2014, in the School of International Service building at American University in Washington, D.C

In: Annual IMI Conference-Website, 2014

6.9 Case Study: German manager meets Saudi Arabianchairman

Dr. Bauer, managing director of the construction machinery factory “Tiefhoch GmbH”, and the chairman of the Saudi-Arabian construction company “Marsala”, Mr. Muhammed Mubruk, have arranged to meet for a first exchange of information in Riad. The meeting has been preceded by some correspondence dealing with Tiefhoch’s product range in general. Moreover, Marsala’s wish to receive more information about specific building cranes for a major project in Saudi-Arabia has become obvious. Finally, both sides have agreed upon a visit of Dr. Bauer in Saudi Arabia from 3rd to 5th March.

Today is the first encounter of both managers in Mr. Mubruk’s office. The first meeting has been scheduled at 10 o’clock. Dr. Bauer arrives shortly before the appointed time. The door to the office of Mr. Mubruk is open and Mr. Bauer has already spotted him as he is waiting for the meeting. After about 15 minutes he is now asked by the secretary to follow him to Mr. Mubruk’s office.

Instructions for the Role Play

In brackets, you will find instructions for the adequate use of body language.

The following characters are to be casted (all men):

- Dr. Bauer

- Mr. Mubruk

- Two friends of Mr. Mubruk

- Mr. Mubruk’s secretary

Initially, the role play is supposed to show Dr. Bauer’s wrong behavior. After an intensive discussion, a second role play should take place, which shows how to behave interculturally correct.

Source: Rothlauf, J., in: Seminarunterlagen, 2005, S. 28

Review and Discussion Questions:

- Which verbal und non-verbal mistakes of Dr. Bauer became obvious during his meeting with Mr. Mubruk? List them all and then describe how a solution should look like! You should find at least five mistakes.

- How would you assess Dr. Bauer’s intercultural preparation and what do you think is absolutely necessary to deal effectively and interculturally correctly with Arab partners?

- Dr. Bauer arrived in Riad on Monday afternoon and has booked his return flight for Thursday. Do you think that his time schedule will meet the expected requirements of both sides? Give a profound answer!

- During the time of Ramadan you are expecting a delegation of Kuwaiti managers, who will be arriving in Hamburg on Sunday. How should you develop the schedule for Monday with a specific focus on time tables and infrastructural needs (presents for the guests, drinks on the table, lunch, dinner, etc.)? How would you welcome your guests before the dinner starts?