9 Intercultural Preparation and Reintegration

9.0 Statement of the problem

The cost of failure

Unfortunately, many Western companies and individuals fail to face the realities of life and work in the Gulf. Many costly mistakes can be made, both financially and personally. Western companies sometimes believe that simply by dispatching highly qualified and intelligent staff to undertake duties in the Gulf all will be well. Foolish companies will presume that professional qualifications is the overriding requirement and give no weight to the wider mental preparation (and selection) of such people and their spouses. Professional competence is the starting point for selection purposes; what is also needed, in the character of those under consideration for Gulf employment, is an intercultural preparation. Without knowing the peculiarities of Arab culture, business practices and the relevant behaviour patterns, which include a comprehensive understanding of Islam, each expatriate will definitely fail.

In: Don’t they know it’s Friday? 2004, p. 3

9.1 The role of expatriates

International labor mobility is becoming a component in the globalization of industries worldwide. Regions, nations, industries and people are in a permanent state of flux in which geographical mobility plays an important role. Globalization has led to intensified interaction among businesses and their managers from different countries and cultures. It is generally accepted that it is essential for multinational companies to attract, select, train and retain employees who are able to effectively work outside their own national borders (Flyztani & Nijkamp, 2008, pp. 2-3).

This dynamic business environment has introduced the phenomenon of expatriates. They are

“a particular class of foreign workers who are sent on a temporary basis by a parent company located in a given country to live and work in another country, notably as an employee in a subsidiary abroad” (ibid., p.1).

Expatriates have to perform in an unfamiliar work context, and need to handle and adapt to a different way of life and management styles (ibid. p.3).

Windham International and the National Foreign Trade Council, Inc. (NFTC) conducted a study among 180 companies representing small, medium, and large organizations with offices located throughout the world. The companies were mainly headquartered in the Americas (48 %) or the EMEA (49 %) with only few from the Asia-Pacific region (3 %) (Windham & NFTC, 2007, p. 4).

The survey revealed that the majority (56 %) of responding companies deployed more than 100 expatriates (ibid., p. 5). Moreover, 69 % reported an increase in the number of expatriates over the last year, whereas in the 2005-survey, the percentage was just 47 % (ibid., p.6). Only 19 % reported a reduction in their number of international assignments. Prospects regarding the future development were also optimistic, since 65 % of the respondents expected a rising number of expatriates in 2007 (ibid.).

These figures are similar to the survey by Mercer Human Resource Consulting, where 44 % of all multinational corporations questioned had increased the number of their international assignments in 2005 and 2006.

International assignments as career opportunities

Henrick Wegner, Project Director of Netcom Consultants, currently working on the “Tigo Rwanda Project” in Kigali answered questions raised by the students of the University of Applied Sciences Stralsund on 28th May 2010:

Students: What is your best career advice to somebody who has just graduated from university?

Wegner: Do seek maximum exposure by specifically pursuing overseas assignments, ideally with a global company that is head-quartered in Central Europe. Do not mind the tough challenges as they will prove to be your best trainer and valuable for future references. The better you manage to cope with unaccustomed working conditions, the more appreciation you would be able to reasonably expect from your organization, thus making the foundation of your professional career ever more solid.

In. Günther/Kerber/Laudahn/Wiese, Written Assignment, 2010, unpublished

9.2 Intercultural learning and culture shock

9.2.1 Definition of culture shock

Due to the change of the social and non-social environment, the expatriate is confronted with patterns of perception, thinking, feeling and acting that are different from his/her previous “world of implicitness” (Kühlmann, 1995, p.4). The relativity and culture dependency of of our experience and behavioral patterns becomes obvious (ibid.).

This experience of inappropriateness of one’s own behavior in a different culture and the consequent loss of orientation, unstableness and insecurity is often described in literature as the concept of a “culture shock” (Eulenburg, 2001, p. 62).

Oberg introduced the term “culture shock” for the first time to describe the adaption process to an alien environment; from entering the host culture to the successful integration (Wengert, p. 2). To Oberg, the culture shock is similar to a sickness with a certain cause, symptoms and treatment (1960, p. 7).

“Culture shock tends to be an occupational disease of people who have been suddenly transplanted abroad (…). Culture shock is precipitated by the anxiety that results from losing all our familiar signs and symbols of social intercourse” (Oberg, 1960, p. 177).

Nowadays, the term has a negative connotation, which usually implies that the person experiencing it is not willing to adapt and that certain experiences in the other culture have resulted in a shock (Löwe, 2002, p. 10). Layes (2003, p. 130) agrees that the term “culture shock” is deceptive, because people understand it like a severe shock phenomena, although culture shock also embraces soft irritations and confusion when experiencing the otherness of the new culture, which can lead to alienation and rejection of the host culture.

Wagner concludes that a culture shock is the sum of all intercultural confusions, all the times putting one foot in it (1996, pp. 33–34). He thinks that the cause of culture shock is connected to the norms creating meaning in one’s own culture (ibid.).

Kopper and Kiechl (1997, p. 33) clearly state that culture shock is not a illness but a process of adaption after the relocation to another culture, and is associated with the gathering and processing of different behavioral norms and patterns, customs, rites, as well as their own psychological reaction to the unknown. Adler (2002, p. 264) agrees, stating that

“Culture shock is not a disease, but rather a natural response to the stress of immersing oneself in a new environment”.

9.2.2 Culture shock models

The cross-cultural research literature features several terms to describe the development of skills that allow foreigners to function adequately in a new culture. Adjustment, adaptation, and acculturation are the ones most often used and they describe the process and resulting change when people move into an unfamiliar cultural environment. (Haslberger & Brewster, 2005)

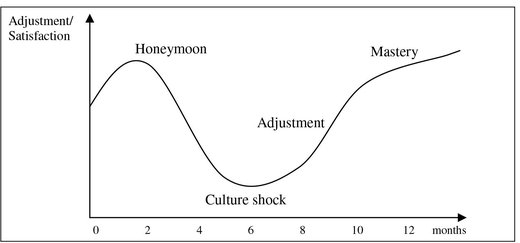

The best known culture shock model introduced by Oberg (1960) describes the four different stages of adjustment: Honeymoon, Crisis, Recovery, and Adjustment. Moreover, the “U-curve” hypothesis introduced by Lysgaard (1955) has been a researchers’ favorite for describing the adjustment process over the last half a century.

The Honeymoon Phase or Euphoria is characterized by fascination and enthusiasm for the new culture having friendly – but superficial – relationships to host country members (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 6). Expatriates enjoy a great deal of excitement when they discover the new culture (Adler, 2002, p. 263).

In the second phase, the actual culture shock sets in. The problems in terms of language, values and symbols create negative emotions, anxiety and frustration (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 6). It is a period of disillusionment and

“(…) a result from being bombarded by too many new and uninterpretable cues” (Adler, 2002, p. 263).

Fig. 9.1: Adjustment in an international assignment: The “U-Curve Hypothesis A”

Source: Lysgaard (1955), as cited in Stahl, G.K., n.d.

After that, when time goes on, the Recovery or Adjustment Phase begins, when the knowledge about the host country is improving, the foreigner can orientate him/herself within the new culture and the attitude towards the host culture improves (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 6). Thus, after the culture shock phase, expatriates start adapting to the new culture, feeling more positive about their host country, working more effectively and living a more satisfying life (Adler, 2002, p. 263). Finally, the Mastery phase begins; reaching a stable state of well-being, where the habits of the other culture are accepted and and anxiety rarely appears.

Fig. 9.2: Adjustment during an international assignment: The “U-Curve Hypothesis B”

Source: Lysgaard (1955), as cited in Stahl, G.K., n.d.

When people are experiencing the culture shock, there are several possible symptoms manifesting themselves in physical conditions, perceptions and behavior. Health impairments can be insomnia, a loss of appetite, digestion problems and high blood pressure (ibid., p. 7; Adler, 2002, p. 265). Moreover, an affected person might also undergo psychological effects like mistrust towards the members of the host culture, the feeling of being constantly deceived and helplessness when confronted with everyday problems. The host culture is blamed for one’s own destiny (ibid.). Ultimately, a change of behavior could become apparent, such as a decrease in performance and creativity, a focus on contacts with country fellowmen, the avoidance of members of the other culture, a resistance to speaking the foreign language, and deprecatory statements towards the host country and its habitants.

The culture shock causes similar symptoms like stress. Therefore, it is also recognized as a stress reaction (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 16; Furnham, 1990, p. 281). During the international assignment, the expatriate is confronted with plenty of daily hassles which can cause some, but feasible problems. However, if they seem to accumulate, the expatriate gets the feeling of excessive demand and dissatisfaction of his stay abroad (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 16). Factors that provoke stress are ambiguity, unpredictability, loss of control, sensory overload (ibid.), role conflicts, ambiguity, and adjustment processes (Udris/Frese, 1992, p. 343). Thus, the stress-related culture shock may take many forms, like anger, anxiety, disappointment, embarrassment, frustration, identity confusion or impatience (Adler, 2002, p. 265).

To reduce the culture shock stress for global managers, Adler (2002, pp. 265–266) suggested the creation of personal stability zones, like going to an international club, watching movies in one’s native language, or checking into a home-country hotel for the weekend top, to reduce stress. Furthermore, it is recommendable to use stress management mechanisms, like meditation and relaxation techniques, keep a journal, or physical exercise. On the job, the expatriate must recognize that he/her will neither work as efficiently nor as effectively as before and consequently also adjust his/her expectations.

The mentioned culture shock symptoms vary in their number, duration and intensity depending on the person concerned (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 16). Factors that influence this variability can only be speculated. The U-curve model has its defects, since it is not clear if the phases can only proceed in this order, if phases can be left out, how long one phase lasts etc. (ibid.).

In 1985 Grove and Toribiörn developed a newer approach, trying to explain the subjective adaption process with the coherence of three psychological aspects: clarity of the mental frame of reference, applicability of behavior and the subjective level of mere adequacy (Kühlmann, 1995, p.8).

9.2.3 Types of reaction to culture shock

The positive adaption to the host culture has been finalized when the expatriate feels comfortable in his/her new environment and established social contacts to “natives” (social and non-work integration), and executes his/her professional task successfully (work integration). The expatriate, in this case Type A, overcomes the culture shock and reaches his original emotional satisfaction level. He combines his accustomed behavioral patterns with the newly learned ones (Synthesis) (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 17), feeling an attraction to the host culture, but preserving the own cultural norms (Integration) (Berry/Kailin, 1995). The international assignment and the conjoint experiences enrich the expatriate’s personality (Eulenburg, 2001, p. 70).

What to expect in China – Dealing with culture shock

(Greg Rodgers)

1. Remember the language difference

Don’t expect everyone whom you encounter to speak English well, why would they? Saying the same thing again only louder makes you look like a newbie traveler and won’t help them to understand any better. The same goes for showing others a map or written words; can you read Chinese?

2. Starting and pointing

All foreign visitors to China, particularly blond or fair-skinned people, receive plenty of attention when in public. People will openly stare at you, expressionless, and sometimes even point you out to friends and family by jabbing a finger in your direction. Pointing is often accompanied with the word laowai which means “old outsider”. You will hear the term often, despite the government’s efforts to curb its usage.

3. Spitting and mucus clearing

Spitting in public and clearing the deepest sinus recesses of the head – with sound effects –are common throughout China – even on public transportation and sometimes indoors! Choking pollution in big cities and excessive smoking are good reasons to send a lot of mucus flying.

4. Personal space is a luxury

Don’t be offended if someone stands just a little too close when speaking to you, or people are calmly pressed against you in crowded public transportation. With such an enormous population, the Chinese do not share the same concept of personal buffer space that Westerners monitor. You will rarely receive an “excuse me” when someone bumps into you or squeezes past while knocking you out of the way.

5. Fight your position

Orderly queues, especially of more than a few people, are generally disregarded in China. As a foreigner, people will blatantly step in front of you, cut line, or push past you to the counter as if you aren’t even there. Again, remember that overpopulation plays a big part in this behavior and do your best to keep cool while holding your place in line. Don’t be afraid to stick elbows out or to shuffle around defensively to keep people from stepping in front of you.

6. Watch out for road rage

Crossing the road in busy cities can be a daunting affair. Drivers rarely observe a pedestrian’s right of way, even if you have a working walk signal! Be cautious when crossing roads; don’t assume that drivers will stop just because they have a red light. You are best off crossing safely as a group with others.

In: http://goasia.about.com/od/Customs-and-Traditions/tp/China-Culture-Shock.htm, accessed: 10/09/2014

However, there are more ways of coping. There is the possibility of “going native”, which leads to the highest satisfaction level in the foreign culture, but causes problems when returning home. Type B – also called assimilation type – substitutes his behavioral patterns to the foreign one, absolutely refuses the own culture and loses the own cultural identity (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 17, Thomas/Hagemann, 1992, p. 179, Berry/Kailin, 1995). This coping behavior does not lead to better acceptance in the host culture On the contrary; the expatriate even loses his authenticity (Eulenburg, 2001, p. 70).

In total contrast to this, there is Type C who does not succeed in adapting to the host country’s culture, not overcomes the culture shock. This is also known as the the separation type, who just preserves his own culture, but does not feel attraction to the host culture (Berry /Kailin, 1995). This marginalization type refuses the host culture, avoids contact to the host country’s habitants and integration does not take place, since this type does not learn new behavioral patterns (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 17). Thomas and Hagemann call this the contrast-type (1992, p.179).

For the last type (D), the culture shock means a crucial crisis, resulting in defense-mechanisms with possibly even severe consequences like alcoholism, because there is a non-attraction felt to the host culture and the own cultural norms do not hold any longer. (Weaver, 1986, p. 112; Berry/Kailin, 1995).

Kühlmann (1995, p. 17) describes two more coping types, the addition type, who is an expatriate capable of using the host culture behavioral patterns, but just doing it selectively. Another rather inefficient type is the creation. In this case, expatriates unite the two cultural behavioral patterns to a new unit, which means a synthesis that is not adequate neither in the own nor in the host culture (ibid.).

9.2.4 Culture Shock: India

When you encounter a new environment, all habits and behaviors that allow you to get around survive at home suddenly no longer work. Things as simple and automatic as getting lunch, saying hello to colleagues, or setting up a meeting become difficult and strange. The rules have changed and no one has told you what the new rules are. Even as far as your understanding of truth is concerned not everybody sees it as binding. In order to get a better understanding what is meant in this context the following example should underline the difficult approach to get familiar with a new culture. There are a lot of things that strike people from other cultures when they interact with Indians for the first time (Messmer, 2009, p. 118–119):

- Lack of order and structure

Life functions differently in India, everything seems to run in its own rhythm. Following schedules, adherence or existence of rules cannot be taken for granted. Everybody follows their own destination, logic, and rhythm.

- Decibel level

Indians tend to speak all at the same time and at much louder volumes than necessary. People are used to living and working in overcrowded spaces and it is thought to be important to raise the voice in order to catch attention.

- Display of emotions

Indians control their emotions far less than foreigners do. Uncontrolled outbursts of irritation, overwhelming appreciation, open anxiety, and declaration of loyalty can be a challenge to deal with.

- Respect for hierarchy

Elders in the family enjoy a special superior status because of their seniority. Most organizations have a very steep hierarchy and authority is often not questioned.

- Lack of private sphere

Colleagues at work and also total strangers surprise you with questions about your age, work experience, marital status, number of children - and even your income. All this is not viewed as a violation of personal space in India. Colleagues at work are very much aware on where their peers stand in terms of monetary compensation.

- Juggling of appointments and multitasking

Appointments are not necessarily written in stone, as they are more considered like a tentative reservation that can be cancelled without notice if anything more important comes up. It is very rare that a telephone conference starts at the scheduled time; most Indian participants will dial in five to fifteen minutes later. When in a meeting, Indians will not switch off their cell phones but take each and every call – it might be an important one. This goes as far as telephone calls being answered while visiting the restroom.

- Peace over truth

In cases of conflicts or disputes, the value of peace comes before truth. This means that you will not be told the complete truth or be told an adjusted version of the story in order to allow the Indian to keep face and continue with a harmonic relationship. Facts can be switched and turned, if it serves a good purpose; there is not only one version of truth.

9.2.5 Culture Shock: Saudi Arabia

From 1991 till 1994 I have worked as a Senior Commercial Adviser for the GIZ (Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) former GTZ. During that time some challenging situations did occur in a completely new environment (Seminarunterlagen, 2012):

“When I came to Saudi Arabia, I was confronted with a Muslim society in which the Qur’an determines the whole life, regardless, if someone is a Muslim or not.

The Muslim day starts very early at about 4.45 am. The exact time depends on the sunrise of this day and is to be found in any newspaper well ahead of the given day. From more than 2,500 mosques the respective loudspeaker informs all people in the area that the time has come to perform the first prayer. There is no escape from receiving this message, especially not from the noise linked to the loudspeakers, because you will find a mosque within a distance of about 200 m. However, after a while, one gets familiar with these circumstances and only those living quite close to a mosque will not find sleep again.

The next time you have to adjust your behavior - now towards your Muslim colleagues - occurs when the second prayer time will take place. At about 11.25 am the colleagues will leave the working place in order to pray. They have two opportunities to perform the praying. Either they go to one of the praying rooms set up at every floor within the building, or they have the possibility to walk to the nearby mosque outside the working place. The overwhelming majority of all governmental clerks decide to go to the next mosque. Why? I presume, in order to avoid working too long. At about 12.20 pm or later, you can continue the collaboration with your Muslim colleagues.

As far as the third and fourth prayer time is concerned an interesting explanation will be given to you. Normally, each Muslim has to pray five times a day. The Saudi interpretation of the Qur’an now says that those who have to travel are allowed to pray only three times. What does that mean in reality? At around 3.25 pm thousands of cars are moving from their home to the next mall. The same can be observed about two hours later when the fourth praying time will take place, with the difference that the cars are now moving home.

The fifth prayer time will take place at about 7.30 pm. If you expect guests from Saudi Arabia, keep in mind that they will not arrive before 9.00 pm. The heavy traffic causes a lot of delays and those who want to pray should be given sufficient time to perform their duties as Muslims.”

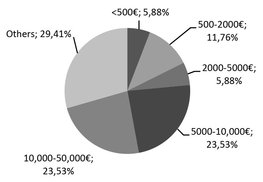

9.3 Failure of expatriation: costs & causes

Expatriates are a major investment for multinational corporations. It has been estimated that the first-year costs of sending employees on intenational assignments are at least three times the base salaries of their domestic counterparts (Wederspahn, 1992).

Still, depending on the respective survey, about 15 to 50 % of the international assignments fail (Thomas/Hagemann/Stumpf, 2003, p. 242), which costs the company about US$ 250,000 to US$ 1,000,000 per failure (Bhagat/Prien, 1996, p. 217).

The study of Black and Gregersen (1999, p. 53) among 750 US-American, European, and Japanese companies about expatriates revealed that between 10 to 20 % of the expatriates have returned early without completing their international assignment, with one third of the managers not reaching the performance expectations, and one quarter quitting the employment afterwards. About this rougly 30 %-group, Althauser (1996, p. 3) found out that third of the expatriate managers had to return prematurely due to an insufficient performance, causing costs of about DM 250,000 (≈ EUR 128,000) per assignment.

Based on a study with only American companies, Keller (1998, p. 320) refers to a premature return rate of expatriates of 15 to 30 %, He estimates the follow-up costs to amoung to three or four times the managers’ annual salaries. Kealy (1996, p. 83) even speaks of early return rates of American managers ranging between 15 to 40 %. Whereas Kühlmann & Stahl (1998, p. 44) assume 10 % to be a realistic premature return rate, Cendant found out in 2001 that 44 % of MNCs were reporting failures in the Asia Pacific region, and 63 % in Europe.

Moreover, Black and Gregersen (1999, p. 103) highlighted the selection of inappropriate personnel, bad preparation, and unreflecting treatment during the repatriation as the main reasons for failure.

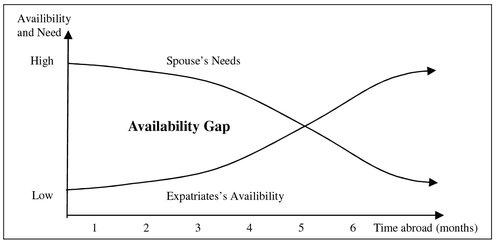

Already in 1982, Tung and also Toribörn recognized the (dis)satisfaction of the expatriates’ spouses and families and their adaption to the new cultural environment as a central determinant for early termination and cultural adjustment of the expatriate. Mendenhall and Oddou (1998) also showed that the lacking adaption of spouses and partners of the expatriate lead too international assignment failures.

Similar explanations of assignment failures are given by the Zürich-Versicherungs-gesellschaft, which states the missing social contacts and personal relations with the local habitants, communication problems within the teams, and adaption difficulties of the family as the main reasons (Saunders, 1997, p.94).

In a survey by Windham International & NFTC (2006, p. 14), however, 10 % of assignments were not completed because expatriatess returned prematurely. The named key factors leadingg to assignment failure were partner dissatisfaction (57 %), inability to adapt (47 %), family concerns (39 %), and poor candidate selection (39 %) (Windham & NFTC, 2007, p. 14). Spouse dissatisfaction has always been the most frequently cited factor (ibid., p. 50).

However, international failures do not necessarily involve a premature return. Bittner and Reisch (n.d., p. 53) see it as a complex term, which also includes a refusal of contract prolongation, missing the targeted objects, just marking the time, lasting personal problems, massive conflicts etc. That can clearly bring up the percentage of failure to about 25 to 30 %, but those costs are difficult to estimate.

As far as international joint ventures are concerned the failing rate is extremely high. Between 50 to 80 % of those business activities are assumed not to be successful (Kealey, 1996, p. 85).

9.4 The expatriation cycle

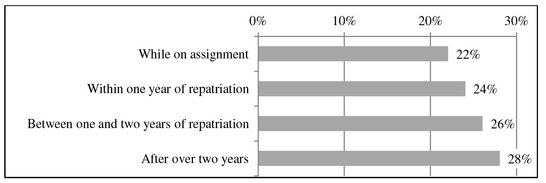

The transition back into the home country can cause problems just like the new environment and lifestyle when entering another culture (Adler, 2002, p. 274).

While abroad, the expatriate changes, the organization and the country change as well, andd during the culture shock phase of adjusting to the host culture, expatriates often idealize their home country, just remembering the good aspects. Then, upon return, the gap between thee way it was and the way it is, and the gap between their idealized memories and reality can be a shock (ibid., p. 273).

“Successful global companies understand and manage each phase of the expatriate global career cycle” (ibid., p. 262).

The reintegration process will be looked at more closely in the second part of this chapter.

9.4.1 Aspects of a successful international assignments

In order to make an international assignment successful, the support of the whole family is needed. Thus, their willingness to relocate is a big step towards successful expatriation.

According to McNulty (2005), the factors influencing the willingness to relocate are: standard of education for children (66 %), company funded home-country visits (59 %), transferring spouse’s attitude towards relocating (57 %), ability to re-establish a support network (56 %), perceived standard of living in host-country (54 %), and the impact of relocation on trailing spouse’s career meaning the dual-career issue (35 %).

Moreover, important factors of organizational support for the success are the assistance to set-up internet and email (94 %), housing assistance (94 %), ongoing organizational support also after relocation (85 %), financial and time support for home-country visits (82 %), and the provision of extended time for the entire family to adjust including expatriate’s spouse (82 %). 26 % also listed the pre-departure training for the trailing spouse. For him or her, there is a strong need to establish or improve a direct communication link between the sponsoring organization and the spouse or partner, irrespective of their non-employee status with the organization (ibid.).

Windham International & NFTC (2006) identified major expatriate and family support initiatives:

- Better candidate assessment and selection

- Better assignment preparation

- Career-path planning for better cross-border skills utilization upon return

- Effective communication of assignment objectives

- Mandatory cross-cultural training

- More communications and recognition during an assignment

- Development of company intranet for expatriates

- Mandatory destination-support services

9.4.2 Role of the family

Companies sending their employees on international assignments do not only send one member of the staff but in many cases the family is part of the decision to go abroad. The influence of the family on the job as well as on the wellbeing of all family members was part of many studies. The families’ disposition to go, the adaption to and familiarization with the new culture has a great impact on the expatriates’ success and well-being (Kühlmann, 1995; Black/Gregersen 1990, Harvey, 1985; Mendenhall/Oddou 1985, Tung, 1981).

To specify the adaption problem for the spouse, there are three characteristics according to Kühlmann (1995, p. 20):

- Firstly, the spouse or partner is often forced to do nothing in the new country, because only the expatriate has been granted a work permit.

- Secondly, the partner experiences the phenomenon of the culture shock more intensively. The expatriate is supported by the familiarity of his work and his colleagues; the spouse has to manage the every-day-life in an alien culture, different habits and language.

- And lastly, compared to the expatriate, the partner normally is not so skilled in the foreign language and has to struggle with communication barriers and additionally has to handle the family’s needs.

Hence, the expatriate him/herself has the continuity of work, the children have the continuity of school, but the spouse has to give up his/her entire social life, the family, the friends and also his/her employment, and with that a feeling of usefulness. So the expatriate’s spouse is confronted with the greatest burden especially in the beginning phase (Adler, 1991). Although, as mentioned above, the spouse does not possess the language capability like the expatriate, he/she is responsible to build up the new household, doing the necessary phone calls and assuring the medical support etc. (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 41).

Aram et al. (1972) discovered that the positive support of a spouse to go abroad is important to the professional success of the expatriate.

Fig. 9.4: Performance evaluation of expatriates with or without the influence of their wives

Source: Own graph based on Stoner/Aram/Rubin, 1972, p. 310

Thus, it is not decisive for the acculturation of the expatriate if he/she is married, but if he/she gets emotional support of the family. Therefore, the spouse and children can be an important stress-coping resource, if they are not overstrained themselves with the experience of the alien culture (Fontaine, 1986). Additionally, there is the danger of the “contagion effect” of culture shock, meaning that the adaption difficulties of one family member influences the performance of the other, as it is described by Adelmann (1988, p. 192):

“For families that experience severe culture shock, mutual dependency can intensify the stress rather than solidify relational bonds.”

Since the dissatisfaction of the spouse is one of the most frequent reasons for expatriation failure as depicted above, companies relocating their staff should include the potential expatriates’ families within the selection and preparation process (Kühlmann, 1995, Tung, 1984). But reality still varies from the theoretical ideas. None of the questioned Spanish companies of the Deloitte and Touche survey (2003, p. 9) included the spouse or partner in the process of the expatriates’ selection. In the 2000 Survey of Key Trends in European Expatriate Management (PricewaterhouseCooper, 2000) the five least important criteria for selection of candidates were listed as: intercultural adaptability of the spouse, children’s educational needs, emotional resilience, spouse’s career (dual career issue), lifestyle suitability. It is interesting that these five least important criteria were also the most common reasons given for assignment failure (McNulty, 2005).

McNulty accentuates the role of the accompanying spouse as well as one of the most critical and important factors influencing international assignment success, since lack of spousal and family adjustment can have a direct impact on an expatriate employee’s performance.

In the following, the study of Windham International & NFTC (2006) will be analyzed. The survey revealed that the majority of expatriates were male (80 %), 60 % were married and 54 % had children accompanying them during an assignment (ibid., pp. 22–24). 82 % were accompanied by a partner. Whereby 51% of the partners had lost their employment due to the expatriation and remained unemployed.

Family challenges indicated by the respondents were children’s education (14 %), family adjustment (13 %), and partner resistance (13 %) being the most critical issues, followed by location difficulties (12 %), cultural adjustment (11 %), partner career (10 %), and 9 % even mentioned language difficulties (ibid, p. 43).

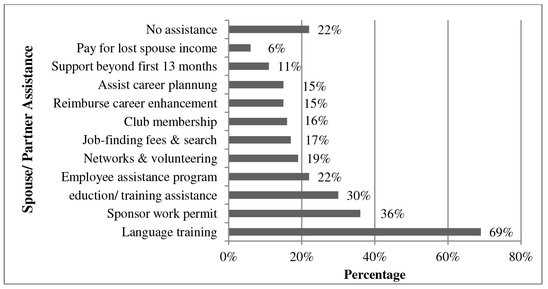

When asked about how companies assist spouses or partners, 69 % of respondents named language training, 36 % work permits, 30 % education/training assistance and 22 % employee assistance program services (ibid., p. 46).

In contrast to a Spanish company survey, where none of the questioned companies paid for the subscription at a sports or social club (Deloitte & Touche, 2003, p. 13), here 16 % offered a club membership (Windham international & NFTC, 2006, p. 46). However, only 17 % assisted in the job finding in the new country (ibid.), whereas this was offered by 27 % of the participants in the Spanish survey (Deloitte & Touche, 2003, p. 9).

Cultural Shock

(Beniers/Hundt)

Imagine an American visiting Japan. At first sight everything looks like at home: hotels, taxis, neonlights etc. Soon the American is going to find out that there are big differences under the surface: If the Japanese nods his head, this doesn’t mean that he agrees. It just means that he understands. When Japanese smile, it doesn’t mean that they are delighted. This way the first feeling of well-being can change into a feeling of disorientation and insecurity. Especially people who spend a long time in a foreign country go through this experience. This phenomenon is called cultural shock. The first to use this expression was the Amercian anthropologist Oberg.

In: International Business Communication for Industrial Engineers, 2004, p. 106

Fig. 9.5: Spouse/Partner Assistance

McNulty (2005) mentioned five top factors for the success of spousal adjustment: a strong and stable marriage (99 %), access to technology like the internet (96 %), organizational assistance (94 %), degree of intimacy with other expatriates (87 %), and transferring spouse’s overall job satisfaction (76 %). 40 % also named children’s adjustment as essential.

There are different opinions at what age children should be involved in an intercultural preparation program. IFIM argues that those trainings are only relevant for teenagers from 16 years and older, because younger children lack the capability of mentally preparing for situations that are not immediate (IFIM, 2002/3, p. 3). It is more about responding to their emotions and preparing them for the relocation, and for that there are books helping the parents and the children to deal with the issue (ibid., p. 4). There is also the possibility that parents and their children visit interactive websites like www.ori-and-ricki.net, and web sites that prepare especially children for their adventure, like http://www.ipl.org/youth/cquest/.

A different view has Angelika Plett from mitteconsult Berlin (2009, p. 41) who describes the general situation for the children as:

“They go into a totally different environment, they leave their friends, they leave whatever they know and they are familiar with. They have to dive into a new culture with a new language. And they need support as well. Only a few companies are doing it right now and only a few are doing it with the spouses.”

As far as the age of the children is concerned, she says (ibid.):

“Well, school kids and then from a very early stage on: 7, 8, 9 years old, you could do that. But it is more a child appropriate approach like painting things and talking about what is missing and also having a discussion between the child and the parents. So that the parents are aware of what it means for the children to leave everything behind them. It is not their choice. They are kind of the victims of this situation and they feel like this. And so they need support.”

In general, the expatriation must be pitched to the children, presenting them advantages of the stay abroad, answering their questions about the school and leisure time activities, giving solutions to their problems. Since often the most urgent issue is the loss of friends, the family can enable their children to communicate via Internet to keep in contact and prepare parties when visiting the home country (ibid., p. 3.).

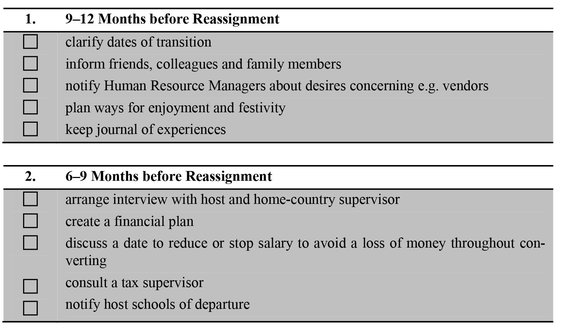

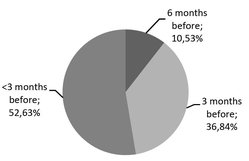

9.4.3 Pre-departure preparation

To the degree that assignees are able to deal effectively with the challenges of encountering new cultures, their assignments will be successful. Thus, effective preparation, support and training for international assignments need to be based on sound research-supported models of the skills required to meet the challenges of those assignments for the assignees, their families accompanying them, those managing them, and the host with whom they are working. According to Britt (2002, p. 22), the second annual Global Expatriate Study revealed that nearly 40 % of the 709 responding expatriates stated that they were not adequately prepared for the international assignment.

Organizational preparation

Before expatriation, a high amount of organizational tasks has to be solved: obtaining all necessary documents (visa etc.), medical support, finding schooling possibilities for children, finding housing possibilities, making a new car available, etc. (Debrus, 1995a, p. 127)

According to Fitzgerald-Turner (1997, pp. 70–72), MNCs should hire a relocation service in the host country, so that the expatriate can concentrate on the challenges at work. Services provided include obtaining work permits, car and home insurance, locating housing, finding doctors and sorting out health care issues, selecting schools, and helping to assimilate in the new culture.

In Spain, 91 % of the companies pay for the relocation of the family, the same percentage pays the costs linked to accommodation for the first 15 days. All pay for the obtainment of the expatriate’s residence permit, and even 91 % cover those costs for the entire family (Deloitte & Touche, 2003, p.13).

Intercultural preparation

Besides the administrational preparation, intercultural orientation help is necessary. MNCs should also provide pre-departure assistance and ongoing consultation for expatriates and their families. It is crucial that, at the very least, basic language skills and cross-cultural training is offered (Fitzgerald-Turner, 1997, p.72). Training can help the manager and spouse to cope with adjustment difficulties; cultural training, language training, and practical training all seem to reduce expatriate failure (Vögel, 2006, p. 7).

The goal is to prepare the expatriate and the families for the new situation, sensitize them for different behavior and beliefs in the host culture, and achieve integration (Debrus, 1995a, p. 124). Pre-departure training programs administered by the parent company can ease the transition of the expatriates and facilitate expatriate adjustment to amenities, general living conditions and social interactions (Yavas/Bodur, 1999). Pre-departure preparations should include the teaching of effective communication styles, providing insight of stress management strategies, teaching expatriates how to work in teams and to manage conflicts, and how to manage relationships across the globe (Koteswari and Bhattacharya, 2007).

In general, intercultural training methods can be differentiated into information-oriented, culture-oriented and interaction-oriented training as it is illustrated in Fig. 9.6. The degree of active participation also greatly differs between the training programmes. Beyond that categorization, some intercultural training methods and measures wil be described in the following.

Linguistic preparation

Sufficient fluency of the host country’s language is essential to get integrated into the new culture. The linguistic preparation aims at imparting the language requisites to manage the new job task, but also for the integration in the host culture. The integration of the family in the linguistic preparation is vitally important, since the spouse and children are in more contact with the inhabitants and host culture (Debrus, 1995a, p. 125).

An exclusive reliance on English diminishes an expatriate’s ability to interact with the host country nationals, a willingness to communicate in the host country language can help to build rapport with local employees and improve the expatriate’s effectiveness (Hill, 2003, p. 617). Williams, associate of Mercer, states that linguistic and intercultural preparation can increase drastically the probability of international assignment success (Paus, 2006). At present about 75 percent of the companies questioned by the Mercer Human Resource Consulting survey offer language courses (ibid.).

Expatriates have a great interest in information about the host country, its people, habits, and culture. But it is not sufficient to supply tourism information. More important are facts about the living conditions, schools, shopping facilities, transportation possibilities, insurance and judicial questions, and medical support. It has been suggested that expatriates should receive training in the host country’s culture, history, politics, economy, religion, and social and business practices (Hill, 2005, p. 629).

Derbus demonstrates the manner how the Henkel KGaA solves the problem. They provide the expatriates with country information maps and more literature for the first meetings and get support by country reports of former expatriates (Debrus, 1995a, p. 126). More and more companies now include spouses in information sessions with relocation managers prior to the transfer (Hill, 2003, p. 616). DuPont, for instance, invites the spouse to attend an orientation session where they can ask specific questions about any aspect of the transfer (Vögel, 2006, p. 3). They feel that the relocation is very much a family dislocation and the extent that the spouse can feel a part of each step is important.

Former expatriate’s information

Former expatriates are helpful to support with insider know-how. However, the advice is very subjective and depends on the experience the expatriate and his family had made and could lead to discouragement (Debrus, 1995a, p. 126). Shell International employees simply contact Outpost, a network of 40 information centers set up for Shell expatriates and their families in 30 countries in the world. These Outpost Centers, staffed by the spouses of Shell’s expatriate employees, provide a comprehensive and personal briefing service to anyone who is considering or has accepted an international assignment. Moreover, the Outpost centers have structured welcome groups who help new families to get familiar with the new situation after their arrival (Sievers, 1998, pp. 9–10).

Culture Assimilator

During the last years, critical incidents have been modified to better conform to the requirements of a successful intercultural training. This process resulted in the development of the Culture Assimilator, which consists of several critical incidents that describe “incomprehensible” reactions of members of another culture. For each incident several answers are offered. The trainee is requested to decide on one of these possibilities and can read the feedback on his chosen answer. If it is not the right one, the reader has to try it again. When appropriate, the most important pieces of information are summarised at the end of each section. (Bittner, 2006, p. 2) Contents of these descriptions are anxieties, expectations, uncertainties, ambiguities, prejudices, attitudes, hierarchies, values and sense of time, just to mention some (Götz/Bleher, 2000, p. 37).

A major benefit of culture assimilators is the existence of both culture-general and culture-specific assimilators. The content is adaptable to a very high degree, because if existing assimilators are not suitable, the trainer can easily create his own assimilator by adjusting it to several factors such as gender, age and aims of the participants. (Landis/Bennett/Bennett, 2004, p. 69)

In role plays, a new situation is created in which the participant has to cope with a problem or task he or she is normally not confronted with, using his recent awareness and knowledge of the foreign culture. (Götz/Bleher, 2000, p. 43) The chosen situations should be relevant to the trainee’s job or situation. It is a good possibility for the attendees to try to participate with unfamiliar situations in a safe environment, getting the chance to try it again, and compare their own approach and solution to the other participants’ ones.

Furthermore, the future expatriates receive feedback, so that they can recognise their faults and get the opportunity to improve their intercultural skills. Role plays mostly motivate people, but there might still be some who feel uncomfortable with acting in front of others. In that case, the learning effect is inhibited by emotional rejection. (Landis/Bennett/Bennett, 2004, p. 61)

InterCulture 2.0 – The world’s first e-intercultural business game

We play the game at four different places of the world. Four teams with 3-4 members each are connected by internet and webcam in a virtual classroom. Each team represents an enterprise that is acting on the world-market for drinking bottles.

The market is highly competitive. Therefore, the teams have to co-operate, i.e. build up alliances or joint ventures. In this context it is necessary to negotiate across cultures and languages, to make decisions with partners from other parts of the world. The game consists of 6 business periods and will take seven weeks. Because of the differences between the time zones team will meet only for one virtual conference a week. The conference takes 3–4 hours and will be supervised by intercultural coaches. The supervising coaches of the four countries will evaluate these “live” sessions and are thus able to give support to their coaches.

During the week the coaches (team member) do their “normal” work. Via the e-platform, they have a lot of opportunities to communicate with each other (via mail, voip, forum, chat) or to learn more about the cultures of their partners of about intercultural competence.

Simulation games

Simulation games are experiential exercises, in which the trainees re-enact situations which illustrate the contrastive features of different culture groups. Values, social behaviour or forms of motivation of culture groups are possible issues dealt with in the simulation. (Götz/Bleher, 2000, p. 39)

One simulation game which has become very famous is called “BaFá BaFá” and was established by Robert Shirts. In this game, two completely different cultures are created. Members of the Alpha culture place a high value on relationships whereas the Beta culture is a rather materialistic trading culture. After the members have learned the rules of their culture, they are exchanged. Possible results like stereotyping and misunderstanding are discussed later in the debriefing phase. (Shirts, 1974, p. 23)

The game is mostly used for people who are going abroad for a longer period, and therefore need the knowledge about communication barriers, value differences, the reduction of prejudices and many more. It is a good opportunity to test and improve your own behaviour within your culture and in exchange with other cultures in a safe environment. Many simulation games take at least three hours, which might be a disadvantage, if the time frame of the whole training is strictly limited. (Landis/Bennett/Bennett, 2004, p. 63)

With the help of these experiential methods the trainees get the impression that cultural differences can influence relationships in a negative manner, which can also have an unfavourable impact on the way of living and working in the host country. On the other hand, trainees have to learn that there are not only disadvantages, but also many positive influences. One must neither suppress his own nor the foreign culture, but gain the positive from the differences. (Puck, 2006, p. 19)

It is advisable to arrange a short 5–7-day trip before the formal departure. Those short pre-expatriation visits of the expatriate and his or her partner is a possibility for the expatriate to meet the new colleagues and for the accompanying partner to look for accommodation and register the children in schools (Derbus, 1995a, p. 127). This short trip cannot prepare the expatriate for the habits of a culture, but it can shorten the preparation period and encourage the willingness for expatriation.

The study of Deloitte & Touche (2003) shows that the majority of 64 percent of the questioned companies in Spain paid for the look-and-see-trip for the expatriates and the accompanying partner to get familiar with the new destination. 18 percent only paid for the expatriate him-/herself and another 18 percent did not pay a look-and-see-trip at all.

9.4.4 Expatriate support

There are three categories of expatriates’ support according to Schröder (1995, p.146): Professional support, administrative support, and psychological support. The professional support provides general information and gives the expatriate some specific information about the job, takes care of a contact person within the organization, or a cultural mediator and so on (ibid.). Administrative support involves all tasks necessary for the relocation, like remuneration calculation, transfer tasks like running errands and finding housing possibilities (ibid). Many companies engage a professional relocation service for that purpose. Normally, much of those tasks had to be fulfilled before the departure, but must be carried on afterwards as well (ibid.). Psychological support is confronted with the challenge of helping the expatriate and his/her family with the adjustment process and settling in, and preventing or alleviating stress situations that in the initial phase tend to be a factor (ibid.).

Black et al. (1991) argued that the degree of cross-cultural adjustment should be treated as a multidimensional concept, rather than a unitary phenomenon as was the dominating view previously. In their proposed model for international adjustment, Black et al. (1991) proposed two major components of the expatriate adjustment process. The first aspect, anticipatory adjustment, includes selection mechanisms and accurate expectations, which are based on training and previous international experience.

However, the proper level of anticipatory adjustment facilitates the second major component, the in-country adjustment. This component consists of four main factors: job (role clarity, discretion, conflict, and novelty), organizational (organizational culture novelty, social support, and logistical help), non-work (culture novelty and spouse adjustment), and individual (self-efficacy, relation skills, and perception skills) factors (Shaffer, Harrison, & Gilley, 1999). Thus, in-country adjustment influences three main dimensions of adjustment:

- adjustment to work.

- adjustment to interacting with host nationals.

- adjustment to the general non-work environment.

This theoretical framework of international adjustment covers socio-cultural aspects of adjustment and it has been supported by a series of empirical studies of U.S. expatriates and their spouses (Selmer, n.d., p. 8).

Nevertheless, there are several deficits when looking at the MNCs performance of expatriation support. The three main shortcomings are the fade-out of family problems, the lack of further on-site training and preparation, and missing help for unpredictable difficulties (Schröder, 1995, p. 149).

It is important to consider that the expatriation support is a social resource, there are several sources (colleagues, mentor, family), but also different manners of social support (ibid., p. 156). Due to that, expatriation support must only be used in short term, but as a support system at all times during the international assignment (ibid.).

Adjustment to the general non-work environment

In order to adjust to the non-work environment, stress coping has to be considered, since it is proved that culture shock shows similar signs to stress.

Psychologists have proposed two approaches to cope with expatriate stress: Symptom-focused strategies and problem-focused strategies (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Symptom-focused strategies are used to diminish emotional distress by attending to behavior and expression, physiological disturbance and subjective distress. Problem-focused coping strategies are efforts to take constructive action to change the situation creating the stress and address the problem and minimize the anxiety and distress (Folkman et al., 1986). Expatriates who use the problem-focused coping strategy will be able to cope better with the stress than the symptom-focused coping strategy. Hence expatriates should be trained in using the constructive coping strategy (Koteswari/Bhattacharya, 2007).

Furthermore, practical training is aimed at helping the expatriate manager and family ease themselves into day-to-day life in the host country. The sooner the routine is established, the prospects are better that the expatriate and his/her family will adapt successfully. One critical need is a support network of friends for the expatriate (Vögel, 2006, p. 11). One of the main burdens of expatriates is the breaking up of social relationships (Fontaine, 1986). One solution is the expatriate community, which can be a useful source of support and information, and can be crucial for helping the families adapt to the foreign culture (Hill, 2003, p. 617). The integration into social networks can help to prevent psychological and physical health problems and family crises (Fanning, 1967, Loewenthal/Snedden, 1981).

Moreover, social contacts help with their experience in the foreign culture, for instance how to handle errands etc. They enable the expatriate to deal with the confusing impressions and negative feelings by just sympathetic listening and convey the feeling of appreciation, belonging, and trust (ibid.). Nowadays, the Internet is a potential social contact using expatriate websites like www.expatexchange.com. Social contacts are a cornerstone for the overall success. They enable the expatriate to integrate and handle the new cultural environment (Schröder, 1995, p.154).

Both culture novelty, which is the perceived distance between the host and home cultures, and spouse/family adjustment have been found to be significantly related to expatriate adjustment (Black/Gregersen, 1991). Lower levels of perceived discrepancy between host and home cultures (e.g. less cultural novelty) will facilitate expatriate interaction and general adjustment (Shaffer/Harrison/Gilley, 1999). Therefore, Sievers (1998, p. 9) makes suggestions on how MNCs can support the trailing spouse and families of expatriates while on an international assignment. MNCs should help the spouse to find employment, since the spouse needs the possibility of self-fulfillment (Debrus, 1995b, p. 166). Since, the non-work factors, culture novelty and spouse adjustment, are important direct effects of interaction and general adjustment, cross-cultural training for expatriates and their spouses, whose own adjustment will likely be affected by culture novelty, is vital for the success of international assignments.

To get familiar with the new environment is always a challenge, but insufficient language skills, loneliness, boredom and a sense of meaninglessness are much more challenging (Adler, 2002, p. 312). Expatriates’ wifes or the non-working partners feel alone and sometimes misunderstood, which leads to demotivation and frustration. For that purpose, some internet addresses like www.expatwomen.com or www.femmexpat.com can be seen as an additional help. Certainly, this can also apply to husbands or male partners.

The Henkel corporation supports the spouse integration with systematic language courses, including them within pre-departure preparation, trying to find employment possibilities within the company, administrative support for work permits, and the help to find employment opportunities in other companies (Debrus, 1995b, p. 166), since higher levels of logistical support will facilitate expatriate interaction and general adjustment (Shaffer/Harrison/ Gilley, 1999).

In the beginning of the assignment, the work load for the expatriate is very high because he or she has to get familiar with a lot of different tasks in a completely new environment. There is less time left to take care of the family and the kids, exactly at a time when the family needs attention and support. Therefore, Van Swol-Ulbrich suggests to invest as much time as possible for the family, when expatriates arrive in a country (2007). It is up to the company to understand these needs. The expatriates should get some additional time, especially at the beginning of his job, to take care of tasks directly or indirectly related to the family, like school transfer, Kindergarten, the distance to the next supermarket, the availability of the car and so on. Van Swol-Ulbrich states that the first three months are like the first 100 days in office of a new government. They are crucial but you can get away with a lot during this time, since the employer will understand that the expatriate might need to take off an afternoon or to come in a little later because of things that had to be done at home (ibid.). If the expatriate does not take advantage of this, the first 100 days will be quickly over and the employer will no longer be so supportive.

One of the most challenging questions to be raised in this context is the future of the accompanying partner (Adler, 2002, p. 316). The spouses/partners often engage in cultural or charitable tasks, or leisure time activities, although that does not help their career development (ibid., p. 167). Additionally, the possibility to start another academic study is not promoted in many countries due to foreigner quota, or acceptance of foreign diploma (ibid.). At least there is now a chance within the European Union, since restrictions have disappeared. More frequently today the question focus on identifying ways for the spouse to continue a career while living abroad. One solution could be using the internet for dual career possibilities, for instance www.netexpat.com, www.overseasjobs.com, www.partnerjob.com, www.r-e-a.com, www.focus-info.org, www.outpostexpat.nl.

Why Worry?

(Unknown)

There are only two things to worry about;

Either you are well or you are sick.

If you are well, then there is nothing to worry about;

But if you are sick, there are two things to worry about:

Either you will get well, or you will die.

If you get well, there is nothing to worry about.

If you die, there are only two things to worry about;

Either you will go to Heaven or Hell.

If you go to Heaven, there is nothing to worry about;

But if you go to Hell, you’ll be so damn busy shaking hands with friends,

You won’t have time to worry.

Adjustment to work

According to Yavas and Bodur (1999) job/task characteristics and organizational variables are also believed to affect expatriate adjustment like role ambiguity or role clarity, role discretion (Black, 1988; 1990), role conflict and role novelty (Black, 1988) and organizational culture and size (McEvoy/Parker, 1995). Role clarity and role discretion will facilitate expatriate work adjustment, whereas role novelty and role conflict will inhibit expatriate work adjustment (Shaffer/Harrison/Gilley, 1999). The significance of three job-related factors (i,e., role clarity, role discretion, and role novelty) highlights the importance of job design to the success of international assignments. This suggests that multinational firms should place more emphasis on designing global positions that expatriates have more clearly defined jobs and greater decision-making authority (ibid.). Additionally, greater levels of pre-departure training may be necessary for expatriates expected to experience higher levels of role novelty (ibid.).

Moreover, the quality of work relationships is crucial for the success of any assignment. Relationships between superiors and subordinates who are from different cultures form the significant aspect of multi-national organization effectiveness (Ralston/Terpstra/Cunniff/ Gustafson 1995). Higher levels of social support from supervisors and coworkers will facilitate expatriate work adjustment (Shaffer/Harrison/Gilley, 1999). Companies which are successful in assimilating non-natives into their workforces provide training not only to the expatriates but also to their local supervisors (John/Roberts, 1996).

Beneficial for the challenges at work is the allocation of a tutor or mentor that helps to integrate the expatriate in the new working environment. This mentor is the contact person on-site and has a pate function. The help of a tutor encompasses: personal adviser, giving the expatriate a feeling of security, giving evaluations and feedbacks and be a source of formal and informal social contact, and prevents professional isolation (Debrus, 1995b, p.168; Koteswari & Bhattacharya, 2007). To fulfill the task of a mentor, there is a need for continuous dialogue which is based upon regular meetings and an open exchange of opinions (Schröder, 1995, p. 148, Koteswari/Bhattacharya, 2007).

Negotiating across Cultural Lines

(Claudio Guimaraes)

I was on a three-week trip to Germany from Brazil in order to buy special breeds of cattle from European farmers. One of the strangest things about the Germans was that they didn’t give us any special treatment. In Brazil, if someone is seriously interested in buying our product, we give them preferential treatment in order to get the deal done. We spend time making sure they are comfortable and that their needs and wishes are met. The German farmers asked some polite questions aobut our home country, but they did not discuss prices or other business matters. At the end of the trip, they showed us the prices and bid and payment conditions. We made our bid and they said yes or no, but they did not chat about the offer.

In: Global Smarts, 2000, p. 212

Experience has shown that it can have a negative influence if the colleagues are country fellowmen that make the expatriate insecure with negative talking (ibid.). But helpful colleagues and supervisors are a social resource for the expatriate and can reduce stress and prevent stress reactions (Udris, 1982). It is even proven that social support of the spouse and family cannot substitute the social backing of fellow workers (Schröder, 1995, p. 154). This social support has the characteristics of informational support, looking at advices, hints, and information, and the appraisal support, giving the expatriate feedback about his/her behavior and work (Schröder, 1995, pp. 154–155).

Company picnic

(Terpstra/David)

The managers of one American firm retired to export the “company picnic” idea into their Spanish subsidiary. On the day of the picnic, the U.S. executives turned up dressed as cooks and proceeded to serve the food to their Spanish employees. Far from creating a relaxed atmosphere, this merely embarrassed the Spanish workers. Instead of socializing with their superiors, the employees clung together uneasily and whenever an executive approached their table, everyone stood up.

In: The Cultural Environment of International Business, 1991, p. 175

Within the professional area, it is often up to the expatriate if he/ she is accepted by his/her colleagues. Efforts to learn the host language are positively evaluated. Another strong advice is that expatriate among one another should not speak in their home country language, because they separate themselves from the others and create an atmosphere of mistrust (Debrus, 1995b, p. 174).

Adjustment to interacting with host nationals

Previous international experience and fluency in the host-country language have significant, direct effects on expatriate interaction adjustment.

The social integration of the expatriate and his/her family depends a lot on their ability to speak the host country’s language, since it is a powerful mean to communicate and interact. Language skills help to adapt to the new environment and to understand the new culture (Debrus, 1995b, p. 175). Despite the prevalence of English, an exclusive reliance on the same diminishes an expatriate manager’s ability to interact with host country nationals. Knowledge and fluency in local language enable expatriate to understand and communicate effectively. Expatriate should be definitely trained in the foreign languages in view of the future need (Koteswari/Bhattacharya, 2007).

Moreover, the number, variety and intensity of social contacts that are established during the expatriation with fellow countrymen and members of the host country, are determinants for a successful adaption to the foreign culture (Kühlmann, 1995, p. 20). Those contact persons can support the interpretation of the initially strange experiences in the host country and can serve as a role model for adequate behavior (ibid., p. 21). Thus, when the expatriate is sent on the assignment to the host country, he or she will get better adjusted and will be less frustrated by cultural differences than expatriates who are isolated and have less communication with the host country nationals (Hanvey, 1979; Selmer, 1999).

SIETAR

The Society for Intercultural Education, Training and Research (SIETAR) was established in 1974 in the United States, by a couple of professionals with a specific focus on all kinds of intercultural learning. Originally it was called SITAR, but it became SIETAR to involve the aspect of education. The goal of the organization was to provide a platform where new ideas about intercultural theory and training could be exchanged. The members of SIETAR are professionals from a variety of academic and practical disciplines who share a common concern for intercultural understanding. Their objective is to encourage the development and application of knowledge, values and skills which enable effective intercultural and interethnic actions at the individual, group, organization, and community and national levels.

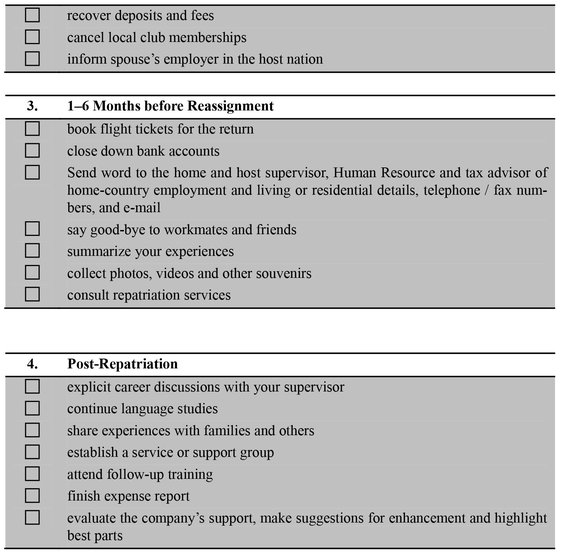

9.4.5 Training methods and their application in the training practice

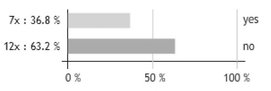

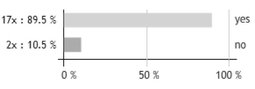

In the framework of university projects and assignments, we regularly try to get in contact with companies in order to find out to what extent intercultural training programs are asked for and which methods are applied in the training practice among others.

In a project study conducted in 2008, training institutes were e.g. asked which methods they used and how high those were in demand. Sixteen institutes kindly filled in the questionnaire. In the following, selected results and a consequent analysis can be found.

Tab. 9.1: Frequency of intercultural training methods used (0 = not offered, 5 = very often)

Source: Warnke/Hanisch, 2008, S. 43

“The frequency was measured on a scale from zero to five, at which zero means that the method is not offered, and five implies that the method is used very often. The table shows the results of the 16 respondents out of 35 training institutes. For a complex and proper analysis of the data, not only mean, but also mode and median were calculated.

The survey showed that discussions, case studies, critical incidents and role plays are the most frequently used methods. Case studies, critical incidents and role plays are methods which were especially developed and adapted for intercultural training; therefore it seems reasonable that these methods are applied quite often. It might seem astonishing that discussions are as frequent as these intercultural methods. But a discussion is a method which is suitable for combining all other methods, so it is mostly part of intercultural trainings. The same reason applies to written materials. Although they are used less on average, the mode shows that most of the institutions which answered the question indicate text materials as frequently provided.

Lectures and films are considered as moderately used. Reasons for this might be that participants are only observers and do not participate actively which can reduce the learning effect. Surprisingly, films are not provided that often as lectures, although they are said to be more lively and motivating than lectures. An explanation which was given by one training institute is that films are often too time consuming and therefore offered rather seldom. Furthermore, the contents of lectures are more adaptable than those of films. Self-assessment is a method which is approximately used as often as films. One reason for this is the limited time frame, too, which makes it almost impossible for the trainer to evaluate the results in a proper way by getting all group members involved.

Language trainings do not play an important role, indicated by all three statistical measures. The mode even points out that most of the training institutes do not offer language courses at all. However, three of the institutes declared language courses as one of the most important methods. This difference is not difficult to explain: some of the institutes have specialised on language trainings whereas others do rather concentrate on intercultural competence apart from language skills.

Comparing the arithmetic means, it appears that immersion, also called look-and-see-trip, is the least frequently used method in intercultural training. Though the mode states that immersion is more likely to be used than language trainings, it achieved one of the worst results by far. Only one institution acknowledged that immersion is one of the most frequently used methods. Immersion is the most intensive form of experiential learning in terms of intercultural training. But considering the high costs of a trip to the host country, many institutes do not offer the method which at the end has to be decided and paid by the companies.”

9.5 Intercultural training institutions – A selection

Working, meeting, dealing, entertaining, negotiating and corresponding with colleagues or clients from different cultures can become a minefield without the support of interculturally trained and experienced experts. Understanding and appreciating intercultural differences will ultimately promote clearer communications, break down barriers, build trust, strengthen relationships, open horizons and yield tangible results in terms of business success. Acknowledging and understanding the intercultural environment is vital in order to be a successful leader in a globalized world. A wide range of institutes provide intercultural training courses on different levels. Only to name a few is hard, because there are so many excellent providers not only in Germany, but all around the world. The choice I have made is based upon experiences and international reputation

9.5.1 Kwintessential

Kwintessential was conceptualised in 2003 by three partners keen to support businesses through the challenges of globalization and internationalization. They foresaw the future demand for language service and solutions as well as culturally and globally savvy insight into business functions. The company started offering language lessons, cultural awareness training, translation and interpreting services. It expanded to encompass further key products such as website design, desktop publishing, conference interpreting and transcription. They started their business in Hounslow before moving to Croydon. From there the business has grown and now operates within the UK from offices in Somerset (HQ), Croydon and Central London. Abroad, the clients are served by local offices in America, South Africa, Switzerland, the UAE and Argentina. They do offer two main areas:

- Localisation, Translation and Language

- Training and Consultancy

9.5.2 CDC – Carl Duisberg Centren

This institution was first founded under the name “Carl Duisberg Gesellschaft” in 1962 as a non-profit organisation offering accommodations for foreign scholarship receivers. It changed its name into “Carl Duisberg Centren” in 1965. Apart from initiating language programmes in the 1960s and 1970s the CDC began to provide their first training programmes for businessrepresentatives in 1976. Since then they have become an internationally operating training institution with branches from Russia, China and Malaysia to Cameroon and several positions in Germany. The headquarters are located in Cologne.

This organisation defines itself as a non-profit service provider in the education and qualification sector. It focuses not only on foreign language programmes for students but also intercultural competence training with private and business customers as well as public sector clients and international institutions. In order to act under the name of a non-profit organisation it targets projects that contribute to society. Limiting communication problems and encouraging people to gain an understanding of cultural diversity has been its intention for years.

To meet own quality standards the CDC collaborate with business experts who bring invaluable practical experience with them. This practice-orientation has always been a major criterion for their performance. Apart from cultural awareness and culture-specific training a coaching service for managers and an assessment tool of the intercultural competence for personnel is also offered. (CDC Website)

9.5.3 IFIM – Institute for Intercultural Management

Founded in 1990, the “Institute for Intercultural Management” in Königswinter, Germany, rapidly assumed its position as a leading provider of cross-cultural training services. It has further gained reputation for scientific research in the field of practice-orientation through its numerous publications. The long-term research about culture-related society differences in business interactions allows a profound and substantiated training service.

A special emphasis lies on meeting the needs of its customers. Their tasks range from a foreign assignment in leading positions, negotiating across national borders or managing multinational teams and helping to assume leading roles in joint ventures and product launches which are covered additionally by its experts. Further, IFIM supports projects for companies that plan to go international from the beginning to the final implementation. In order to improve the quality of all offered seminars, the participants are asked to evaluate the benefit of the training even twelve months after leaving the country. Until 2008, the IFIM has covered a wide range of different countries from all over the world.

However, not just training seminars for Germans are offered, but also American and French people can get an insight into the business practices and cultural particularities. Moreover, the institute provides a detailed preparation service homepage filled with recommendations for current and future expatriates. (IFIM Website)

9.5.4 IKUD – Institute for Intercultural Didactics

The registered association “Institute of Intercultural Didactics” was founded in the year 2000. It is the successor of the same-called institution of the German “Georg-August University” of Göttingen. IKUD gained its expertise through long-term research and is experienced in teaching for more than 30 years now.

Developing and implementing new training approaches for culture-specific seminars lies in the focus of its members. They further publish articles in the field of intercultural didactics. Workshops and lectures to provide a comprised way to convey knowledge are part of their work. Usually, their customers come from companies as well as from organisations which IKUD consults on teaching and training methods. Among their activities is also the development and testing of building block systems that help to improve target group specific trainings. These building blocks are for instance culture-contrast experiences or aim at recognizing own cultural patterns. IKUD is also a partner of municipal projects encouraging intercultural awareness and promoting the integration of migrants. (IKUD-Website)

9.5.5 Further training institutes

- Asien-Pazifik Institut für Management in Hamburg

- Gesellschaft für interkulturelle Kommunikation und Auslandsvorbereitung in Hildesheim

- Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen in Stuttgart

- Institut für interkulturelle Kommunikation in Aachen

- ICUnet.AG in various German cities, Vienna and Shanghai

9.6 Intercultural training at Robert Bosch India Limited

The following program descriptions of Robert Bosch India Limited show some of the elements which can be involved in the company’s intercultural training programs.

9.6.1 Global Corporate Etiquette

Target group: project managers/project leaders

Duration: 1 day

Focus: