Emergency Exercise Design and Staff Education

Introduction

The staff of any healthcare facility cannot be reasonably expected to perform emergency procedures in any type of emergency or disaster setting without reasonable preparation, in the forms of training and practice. Emergency situations are not “business as usual,” and situations are likely to occur in which the standard operating procedures may not be available or even advisable. Moreover, it is precisely such unusual and emergent situations which are most likely to be the subject of detailed review after the fact, in the form of inquests, public inquiries, and civil litigation.

In such circumstances, it is frequently essential for the organization to be able to demonstrate “due diligence” that the facility had taken every reasonable measure to ensure that both the facility and its staff were trained and equipped to cope with the crisis which had occurred. Performance to a given set of expectations cannot be assumed in the absence of appropriate training. If healthcare facility staff are to perform to a specific standard in a given circumstance, it is only reasonable to expect them to be trained or otherwise supported to do so; staff will not do what they do not know.

One of the biggest challenges faced by the Emergency Manager in any type of healthcare facility is the education and preparation of all staff to cope with the various types of emergency situations which may occur. Healthcare facilities are busy places with important work to do, and the challenges of getting staff who are already busy to focus on yet another priority are not small. Moreover, the Emergency Manager must also be aware of the reality that such training cannot and should not distract staff and other resources away from the essential business of the facility. Finally, it is often necessary to overcome a resistance by the Senior Management Team of the organization which, in the absence of a legislative or regulatory mandate, is likely to be, “in an environment of intense competition for limited resources, why should I spend staff time, money, and other resources on preparing for something which might never occur?” This chapter will focus on the types of emergency Exercises and staff education which are possible in a healthcare environment, how to create and conduct each, the various strengths and weaknesses of each, and how to create and operate an effective, dynamic, and ongoing Emergency Management training and education program within a challenging environment.

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, the student will learn the use of emergency Exercises as a staff education tool. They will understand the various types of emergency Exercises and the purpose, strengths, and weaknesses of each. The student will learn how to create, prepare, conduct, and debrief each type of Exercise and how to use the findings generated to create an ongoing and dynamic Emergency Response Plan and Emergency Preparedness Program within a healthcare facility. Finally, the student will understand the documentation requirements for such a program, how such documentation can be used to support Accreditation processes, and how it can be used to support a demonstration of due diligence by the healthcare facility.

Research

With any effort in the creation of emergency Exercises or emergency preparedness education, credibility must be the bedrock upon which subsequent efforts are built. The staff of healthcare facilities are unique in that they are arguably among the best-educated populations of workers in any given society. They are also quite accustomed to functioning in environments in which conflicting demands are made upon their time. As a result, most have learned to be discerning in their response to education efforts, focusing only on what they find to be credible, interesting, and relevant to them personally. They are open to new learning, but, by the same token, will be unlikely to waste their time on any effort which they perceive as being “far-fetched,” unlikely, or simply nonsense.

All information, regardless of the method of presentation, must be authoritative, accurate, and relevant or the audience will simply be lost. All Exercises must be fact based, or they too will simply be wasted efforts. The author is reminded of an episode of the old, American television drama, “E.R.” In the episode, the hospital had decided to conduct an emergency Exercise with a scenario of an explosion occurring in a maraschino cherry factory. Throughout the episode, the staff progressively lost more and more credibility…there simply was no maraschino cherry factory, the “injuries” arriving at the facility were wrong for the scenario used, and the staff, who also had real patients to deal with, grew increasingly frustrated with the Exercise until the entire effort simply collapsed, largely due to staff indifference! There is a lesson there for all Emergency Managers working in healthcare facilities: do your homework, conduct your research, and do not, under any circumstances, insult the intelligence of the staff you are trying to serve, or your efforts will fail miserably!

Once again, the Emergency Manager is not a specialist, but, rather, a sophisticated generalist. The Emergency Manager working in a healthcare facility must be an effective researcher. It is necessary to be able to conduct effective and reproducible research on emergency events and to understand contemporary theories and methods of adult education. By achieving these objectives, the Emergency Manager will be able to develop and operate credible and effective Exercise programs and other emergency preparedness efforts which are well received by the staff.

Adult Education

A good deal of the practice of Emergency Management involves adult education. It is essential for the Emergency Manager to understand some basic theory regarding this subject, as this will assist greatly in the development of the required staff education programs. Being able to stand up and recite facts is simply not adult education. Every effort should be a carefully thought-out and planned event, with a specific set of learning objectives, a method of delivering these, and an understanding of how they are likely to be received and processed by the student(s). Moreover, particularly in the case of adults, not all learning will necessarily occur in the classroom nor will it be unidirectional.

Dr. Benjamin Bloom was a leading educational theorist who taught and conducted research at the University of Chicago and worked from the 1940s to the 1980s.1 He developed a taxonomy of learning, known as “Bloom’s Taxonomy,” which, in simplest terms, explored the methods by which human beings learn different types of information and skills at different stages of their lives. This work continues to be foundational in the study of education. The processes are both detailed and complex, and too detailed for this text; indeed, entire university courses are dedicated to this single subject. For more detailed reading, Bloom’s work and the subsequent analysis of it is commended to the Emergency Manager.2

In summary, for the purposes of Emergency Management education, adult learners learn best by doing. Moreover, learning which has an emotional component will be absorbed and retained better than learning which does not.3 These types of cognitive learning4 represent the foundation upon which the entire use of emergency Exercise play as education is built. Any Exercise which is completely credible, practical, and “hands-on,” and which succeeds in facilitating the emotional “buy-in” of the participants, will result in learning outcomes, including both the short-term and long-term retention of both information and developing skills, which are almost as good as if the participant had taken part in the actual event, instead of merely an Exercise. They key words, once again, are factual, credible, practical, and emotional. All Emergency Management education efforts should attempt to embrace each of these concepts as essential to any program.

Setting Priorities

In almost every Emergency Management education program, there are many projects which could potentially occur. All have the potential to compete for the attention of the Emergency Manager and for the availability of staff to receive the training. Moreover, particularly in healthcare, for most Emergency Managers, this area is not their only area of responsibility; almost all have at least one other major role within the organization, with Emergency Management activities intended to occupy half or less of their working day. Many Emergency Managers attempt to prioritize, using such variable, opinion-based categories as “need to know,” “nice to know,” and even “maybe someday.” Such systems do not function in a vacuum, and both decisions and priorities regarding Emergency Management activities are too often driven by political and other considerations, such as Accreditation, negative press, and public opinion, instead of legitimate need.

Too often, there is a pressure, particularly when Accreditation is approaching and an Exercise is mandatory, to “just do something uncomplicated and easy,” just to tick off a box on a checklist. This often results in an Exercise such as a bomb threat, even when the facility’s own Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment will demonstrate that they are at no particular risk from this type of event. Similarly, there is a belief that nothing short of a fullscale Exercise will meet the need, and facilities will stage such an Exercise when they are nowhere near ready for such a test, usually with disappointing results. Most Accreditation standards in fact call for a demonstration of process, not project, and most such efforts do not really satisfy the intent of the standard in question.

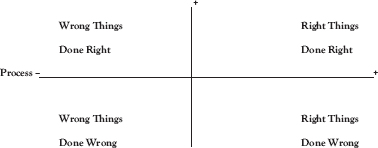

One of the principal reasons for conducting Exercises is to encourage and develop regular and consistent positive behavior. Skills not practiced on a daily basis require reinforcement, or there is a good chance of a bad outcome. Outcome is a matter of both performance and process, and the purpose of any Exercise is to ensure that those playing key roles do the “right thing,” do it correctly, and do it consistently. As the following matrix suggests, there are a variety of potential outcomes to any decision to act, and we want to encourage the correct outcome to occur as consistently as possible, particularly during a crisis.

Similarly, there is a perception that an Exercise which identifies problems is a failure and represents potential embarrassment to the organization. Such a result can often stop an effective Emergency Management program in its tracks, as senior managers make “damage control” decisions regarding processes that they do not fully understand. The first thing that the Emergency Manager in a healthcare facility must make Senior Leadership understand is that any Exercise which identifies potential problems is, in fact, a tremendous success. This permits the organization to identify and fix one or more serious problems without any human cost, before they actually occur. Such efforts are intended to drive the Emergency Management program, including education, and the Emergency Response Plan, making them “evergreen” documents which are subject to a process of continuous quality improvement.5 Any Exercise which fails to identify any problems or opportunities for improvement is, in large measure, a waste of both time and limited resources.

The best tool for driving the need for Emergency Management education and Exercise activities is the organization’s Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment document, described in detail elsewhere in this series. This will provide the Emergency Manager with a set of priorities which are driven by reproducible, research-based, and documented risk exposures, which are ranked by priorities, including probability of actual occurrence and likely impacts in a worst-case scenario. Like all other aspects of the Emergency Management program, this makes the staff Exercise and education program the product of fact, not speculation. The wise Emergency Manager has the top-ranked 20 percent of scenarios in the HIRA absolutely committed to memory.

This makes the decision about Exercises more appropriately one of which type of Exercise to stage, with the priority scenario already identified by the HIRA document. Moreover, one of the biggest challenges with fullscale Exercises is that, just as is usually believed, they are large, complicated, expensive to stage, and disruptive. As a result, they are typically only staged once, and only those staff who happened to be on duty at the time of occurrence have any real possibility of gaining direct experience from it. The vast majority of staff working in healthcare facilities, sometimes for decades, never experience an Exercise, unless they actively seek out participation.

Smaller, less complex Exercises, such as case studies, tabletop Exercises, and functional Exercises, are far less expensive and disruptive and, as a result, may be repeated over and over, until all of the targeted staff members have been reached. The correct approach should be one of many, varied, small Exercises, with the fullscale Exercise coming only when the Emergency Manager believes that the system requires confirmation.

Types of Exercises

Exercises have been conducted as an integral part Emergency Management for a very long time. Like many of the oldest aspects of the practice of Emergency Management, the use of Exercises for training purposes has its origins in the military, the source of many of the original Emergency Managers in municipal and other government settings. The military has always used various types of Exercises for training purposes, and it has long been believed that, like most adult learners, military personnel learn best by doing. The same holds true for healthcare personnel and is already an essential principle of education for various types of healthcare providers, up to and including the old adage in the clinical education of physicians of “see one, do one, teach one.”6

There exists a common misconception in healthcare that unless you have employed a cast of thousands, including the drama club from the local high school, and disrupted the entire business of the facility for a day in what a trained Emergency Manager would describe as a fullscale Exercise, you haven’t really conducted an Exercise. Nothing could be further from the truth. There are, in fact, an entire range of processes which, conducted properly, qualify as useful and valuable Exercises, very few of which meet the usual description of a “real” Exercise. These include case studies, tabletop Exercises, functional Exercises, and fullscale Exercises, and each gathers specific information and/or fulfills a specific purpose in an effective Emergency Management program.7 Each of these will be discussed separately, and in detail in this chapter, and their place in a comprehensive Emergency Management program will be examined.

Case study Exercises, conducted properly, constitute an effective, low-cost, and pain-free method for the staff, usually managers, of any healthcare facility to learn from the problems of others. The process involved is generally quite simple. In all cases, the Emergency Manager must begin by determining a set of objectives to be achieved by the Exercise. Such objectives should be reasonable, practical, and achievable. More than one objective is fine, but don’t “overdo” the objective list; two or three primary objectives are appropriate, with a similar number of secondary objectives listed, if required.

Next, identify the target audience; who will this presentation be received by? Are they front-line staff? A particular group, such as the Emergency Preparedness Committee? Mid-level managers or senior executives? This is an essential step, as the information needs of each group will be different. The Emergency Preparedness Committee or Occupational Health and Safety Committee is more likely to be more receptive to obtaining all of the information, while other managers and executives are challenged by many competing demands for their time. The time demands will also affect the amount of content, with some groups finding value in a comprehensive and detailed presentation, while others will only want the “high points”—executive summaries exist for a reason! In some cases, it may even be prudent to customize the basic presentation, in order to meet the differing information and time demands of various groups.

As a next step, the Emergency Manager identifies an emergency incident which has occurred somewhere in the world, ideally affecting a hospital or healthcare facility, and which meets some or all of the Exercise objectives listed. It may be recent or it may be historical. In some cases, it may be possible to use a situation which has occurred within the facility itself, but there are several limitations to this approach. First of all, the situation to be used must be completely resolved; no ongoing investigation, external review, or potential for litigation should exist. Second, the privacy of identifiable individuals and the confidentiality of sensitive information, such as medical records, must be scrupulously protected. Indeed, if the Emergency Manager intends to exploit such a scenario for an Exercise, it is almost always best to capture the events accurately, but to change the locations and times of occurrence, and to change the names to “protect the innocent.”

The Emergency Manager will then conduct a meticulous and thorough set of research on the incident in question. To begin with, find that information which is readily available within the public domain. This would include sources such as print or broadcast media reports, most of which are readily available on the Internet, using search engines such as Google or Bing. The search can begin with broad terms, such as “hospital + fire” or “nursing home + earthquake.” Eventually, an appropriate case will be identified, and the search will become more focused on the specific event. It is often more effective to use cases which are at least a few months old, as such cases tend to be followed by media sources, with more and more information being recovered, as the review of the incident progresses. In some cases, it may be appropriate to contact the involved facility directly, in order to clarify information. While many facilities are reluctant to share much information, the Emergency Manager probably has a counterpart filling a similar role within the affected facility, and the collegial approach may provide more cooperation and information sharing than might normally be available.

Once all of the information is gathered, the Emergency Manager can arrange it in chronological order and begin to prepare a formal presentation on the incident. This can be done using Microsoft PowerPoint or similar presentation tools. Ensure that all of the facts are included for reporting, but don’t overload individual slides with information. Keeping the facts in manageable “chunks” will prevent the audience from becoming overwhelmed, and missing key information.

They say that a picture is “worth a thousand words,” and in many cases, the media reports will be full of excellent pictures. Add these liberally; and where possible, ensure that you obtain permission from the media source for their inclusion. Bear in mind that such materials tend to be copyright protected, although many would argue that once the information is published online, it enters the public domain. In the circumstances described here, most publishers and media sources will readily agree to the use of their materials, as a not-for-profit public service, so it is always better to ask.

Once the presentation content is complete, the Emergency Manager should review the content and order of presentation both carefully and critically. Is the information factually accurate? Does it unnecessarily disclose any information which should remain confidential? Is there any element of information which might be misleading? Is there sufficient information for the audience to draw appropriate conclusions from, after viewing it? Most importantly, does the presentation actually meet the primary and secondary objectives which the Emergency Manager identified at the beginning of this process? Finally, is it a good presentation? Is there anything in the presentation which might be misleading or confusing? Is it accurate, thought-provoking, likely to stimulate discussion among the audience? Is there, in the opinion of the Emergency Manager, anything which might be done to improve the quality of the information provided?

Next, it will be necessary to select a venue for the Exercise and to obtain permission for its use. The space should be comfortable, well lit, and adequately ventilated. Ideally it will have a digital projector and screen or a large monitor for display purposes. These should be readily visible from all parts of the room. Depending on the size of the room and the group, a microphone and sound system may also be required. Most modern healthcare facilities contain both boardrooms and classrooms which are suitable for such presentations, but all require advance booking with the individual or group, which is responsible for their operation.

The target group for the presentation will need to be identified and invited. This can occur in a variety of ways. If this is an established group, the Senior Management Team or Emergency Preparedness Committee, for example, it may simply be a case of having your Exercise added to the agenda of the existing group. In other cases, individual invitations may be required. This becomes more challenging, since virtually everyone in a leadership role sees themselves as extremely busy, and it is likely that attending your Exercise will, in their minds, compete with other priorities which may be competing for their time and attention.

Tying the Exercise to some other important process, such as satisfying Accreditation requirements, and finding a “champion” among the executive leadership of the organization are both strategies which are more likely to improve attendance. Another fact which will help is the credibility of the Emergency Manager; if the reputation is that such presentations are consistently well researched and interesting, that they yield valuable information, and that they are well run and respectful of the time demands of the participants, the presentations are much more likely to be well attended.

On the day of occurrence, the Emergency Manager should arrive well in advance of the scheduled start time. Audio-visual systems should all be turned on and tested, and the room should be inspected for any problems which are likely to interfere with the presentation. Ensure that any supporting documentation (fact sheets, copies of the presentation, etc.) have been printed and are available to the participants.

If the Emergency Manager decides to use a written debriefing questionnaire, these too should be available, although, in the experience of the author, only about 10 percent of these are ever completed and returned. Ensure that there is a sign-in sheet or similar process at the door, to ensure that you can accurately identify who actually attended the Exercise, and who did not, after the fact.

Start your presentation on time, and also finish it on time. Ensure that the length of the presentation is appropriate; running too long typically loses audience members quickly. Speak loudly and clearly, attempting to hold all discussion until the end of the presentation. Finish the presentation with a brief period for general questions from the audience, prior to beginning the debriefing, but if a question more properly belongs in the debriefing discussion, don’t be afraid to redirect it to that point in the meeting. Don’t forget to thank people for their attendance; their time and projects are as important as yours!

Begin the debriefing by generally summarizing the major facts of the incident; then follow this with a series of questions. Could this event happen in this facility? If this event did happen here, what would be the problems that we would face? How would these problems affect our normal business operations? How vulnerable are we? What would be our strengths in such circumstances? What would we need to do differently? Do we possess the required resources? Do we need to obtain those resources, and from where? Do our staff know what to do in these circumstances? Do our staff require additional training, and of what types? Can we recover from such an event, and what would be required to do so? Are there changes which are required in our Emergency Response Plan and procedures?

Ensure that someone is readily available to take detailed written notes and to capture as much information as possible. Such a discussion can be a virtual “gold mine” of useful information for the Emergency Manager, while raising consciousness about the potential of the event and the value of both the Emergency Response Plan and the Emergency Manager!

Once the Exercise has been completed, thank and release all of the participants. Summarize all of the feedback provided by the debriefing process, and prepare a formal After-Action Report, summarizing the Exercise and its results. Create a file with a copy of the agenda, the Exercise presentation, the debriefing notes, the After-Action Report, and the attendance sheet. Place this file in long-term storage, where it will be available for viewing by accreditors as required and where it will be continually available, if ever required in any type of legal or civil proceedings.

Informally review your actions with respect to the Exercise itself. Did it go well or poorly, and why? Where there any problems or challenges that you did not anticipate? Did you achieve your objectives, and if not, why? What did you learn from this process? What will you do differently the next time? What are the reasonable “next steps”? Exercises are a learning process, and they are a learning process for everyone, including the Emergency Manager! Finally, prepare a summary of the Exercise and the results, and forward this to the Senior Management Team; there is nothing that will generate support for Emergency Management more than a demonstration of positive progress.

Tabletop Exercises

Tabletop Exercises are of particular use to the Senior Leadership group and to the group of predesignated staff and alternates who are expected to fill Command and Control roles during any type of emergency. These Exercises essentially set up the facility’s Command Center, and they will guide the group through the steps required for the actual operation of the facility and problem solving, during a simulated emergency situation.

This Exercise type also has its origins in the military; think back to old newsreel footage of the Second World War, with Generals gathered around a sand table moving markers representing actual military resources. Tabletop Exercises, when created and staged effectively, provide the participants with a thorough orientation to procedures and a level of experience gained through actual practice which, short of actual emergency experience, they could not gain anywhere else.

Such Exercises are primarily about learning management by objectives.8 The experience becomes immersive for the participants, and it provides actual practice at using a Command and Control model which is not in everyday use. It also orients the participants to working as a team and to the special decision making and documentation processes of the Command Center. It can also help to ensure the consolidation and development of trust bonds of a team that may never have worked together before and which may have never run an actual emergency before. Such experience can be almost as good as the “real” thing!

As with any other type of Exercise, the first step is for the Emergency Manager to develop a set of clear objectives. These should be realistic and achievable, and they should be limited in number to two or three primary objectives, and a similar number of secondary objectives, if these are required. With these in place, the Emergency Manager can select a scenario which best meets the objectives selected. There are literally dozens of possibilities in almost every healthcare setting, ranging from a simple missing patient, through a bomb threat, severe weather, a fire, the evacuation of the facility or a mass-casualty incident, to name but a few. The selected scenario will become the “framework” within which the balance of the Exercise script is assembled.

The next step is to conduct formal research on the occurrence of similar events in other facilities, in order to determine precisely what occurred in that case and how the problems were actually addressed. There is no shortage of such information available; following major incidents, almost all hospitals will share their stories, in an effort to help other facilities to avoid similar situations. Next, the Emergency Manager should ensure that they have a thorough and comprehensive knowledge of their own facility, how things operate, what can actually happen, and what cannot. If the Emergency Manager is unsure whether a particular event can occur within a particular facility, the prudent and reasonable approach is to ask someone who actually knows. With the pre-Exercise research completed, it is time to actually write the Exercise.

The Exercise will be composed of a series of discreet elements of information, called “inputs.” In an effective tabletop Exercise, approximately one input for every two minutes of Exercise play will be required. This approach permits the participants a sufficient amount of time for discussion and problem solving, without overwhelming them, and maintains a “flow” of Exercise play. The Emergency Manager should begin with each of the primary objectives and should create two or three inputs which will test that objective in a reasonable way. These will be known as “primary inputs.” Each should be placed on a single sheet of paper.

To illustrate, if the objective is to test the ability of the Operating Room to manage a large-scale, unanticipated influx of patients, and the OR can normally manage 18 cases in a 12-hour period, an input from the Emergency Department that they currently have 25 patients requiring some level of emergency surgery would be an appropriate test. How will the Command Center react: will they attempt to redistribute patients to other facilities or develop other types of improvisation and “workarounds”? This is, of course, but a single example, and there are multitudes of examples throughout a typical facility; it is largely a matter of what needs to be tested.

Next, the Emergency Manager should create a similar set of inputs to be used to test the identified secondary objectives of the Exercise. These might be used to address specific concerns regarding building systems or secondary functions within the patient management process. To illustrate, if a concern has been expressed that one of the emergency power generators requires replacement, perhaps it should fail during the simulated emergency, with an exploration of the result and its impact on the facility. There is, once again, no shortage of potential scenarios; in fact, staff are already aware of these potential problems, probably postponed due to budget concerns or conflicting demands for resources, and many will be happy to tell the Emergency Manager all about them.

With the primary and secondary inputs in place, it is time to review progress for credibility problems. Could the events described in the inputs actually occur within the framework of the selected scenario? Could they actually occur within the facility being tested? How likely are these occurrences? Would the event actually occur in the manner described in the inputs, or does it require adjustment? Any Exercise is about persuading the participants to submerge their disbelief and actually “buy in” to the scenario. When this occurs, the learning outcomes can be excellent, in fact, almost as good as if the participants had taken part in the actual event. On the other hand, if the Emergency Manager presents a scenario, or an event within a scenario, that all of the participants know cannot occur, the “buy-in” is lost, and so are the learning outcomes. Credibility is absolutely essential.

As a next step, the primary and secondary inputs should be arranged in the correct chronological order. The Emergency Manager can then create “filler” inputs, intended to describe the events which logically lead up the primary and secondary inputs. No event occurs in complete isolation. A fire almost never “magically” appears; there might be a patient sneaking cigarette in a washroom, a smell of smoke, and the activation of automated alarms. Fill out the missing information for each primary and secondary input as it would actually occur within that particular facility. Exercise participants know the manner in which the facility works, and this logical flow will assist them in achieving the type of “buy-in” previously described.

Next, create a “starter” input, one which will set the stage at the beginning of the Exercise. Describe the exact conditions which are present at the start of the Exercise play. Is it the middle of the night or the middle of a business day? A weekday or a weekend? What are the outside weather conditions? What are the current occupancy and staffing? Are there specific services within the facility which are currently closed or at or near their capacity? What activities are underway at the start of the Exercise? The provision of this information helps to establish some ground rules for the participants; if you haven’t mentioned that there are six surgeons in the building, they cannot magically appear when the participant decides that they are required!

Arrange all of the inputs which have been developed into correct chronological order. Bear in mind that, in normal circumstances, each event would not be dealt with in isolation, so it is appropriate to mix the various filler inputs somewhat, in order to create the impression of a more random flow of events. It is perfectly appropriate for an event to occur, with the participants wondering why it was included, then move on to deal with describing something else, and then, four or five inputs downstream, the reason for the initial input becomes clear, in a demonstration of cause and effect! With all of this arranged, the Emergency Manager has the basic Exercise script in place, and it is appropriate to move on to the actual delivery of the various inputs.

The method delivery of inputs will be determined to some extent by the resources which are available. At one end of the spectrum, with minimal resources, the Emergency Manager, as the Exercise Controller, can simply sit at the table with the participants and read each input aloud for all to hear.

At the other end of the scale, the Emergency Manager may establish a Control Cell in another room, with individual participants receiving input “updates” in the form of actual telephone calls or radio transmissions from the “Operating Room” or the “Emergency Department” or the “Fire Chief” (all Exercise Controllers). The author has even seen recorded simulations of newscasts describing outside events, played on the display screens of the Command Center. All of these things are possible; it becomes a matter of how elaborate the Emergency Manager wants the Exercise to be and what type of budget resources is available. It is often best, however, to start with small and simple Exercises and then raise the levels of realism as the participants gain experience. They are there to learn, not to be overwhelmed!

The Emergency Manager will then create an Exercise script, using the inputs which have been created. This will provide the guidance to the Chief Exercise Controller to provide the inputs. The content will be included for each input. Also included will be the timing for delivery, the method of delivery, and any anticipated responses or outcomes. This creates a tool which ensures that the Exercise will constantly remain “on track,” that nothing will be forgotten or omitted, and that the experience for the participants will remain as realistic as possible. The script also ensures consistency; one of the advantages of a tabletop Exercise is that its low cost makes it repeatable, ensuring that all members of the Command Center team, both primary and backup, can receive the same training and experience.

The predesignated Command Center, if such a facility exists, is the ideal place for a tabletop Exercise for the Command team. Although most are not purpose-built, the assembly of the facility from kit form can actually provide a useful functional Exercise prior to the commencement of the tabletop. This adds substantially to the realism of the Exercise and also to the learning which is made available to the team.

The Emergency Manager may also choose to use a large classroom, particularly if more than one team is to be trained simultaneously. In this setup, each team will cluster around a single large table; if the ICS, IMS, or HECCS model is in use, this will mean up to nine individuals around a single table, with each of the Key Roles, plus a Scribe. This configuration is useful if primary and backup teams are to be trained together.

The table should be arranged just as it would be in the Command Center, with all of the required documents readily available to the participants. Adult learners typically learn best by doing, and so, rather than have participants describe what they would do upon receiving each input, have them actually do it! They can actually start the Incident Log, record resource requests, and so on. In some cases, trainers use a laminated version of the facility floor plan or a property map as a central reference point in the center of the table. This can provide participants with a physical connection to the information being provided in each input. By laminating the floor plan or map, the participant can actually mark the tool up for planning purposes, using a dry-erase marker. Seating should be comfortable, and lighting should be adequate. The room should be adequately ventilated, and the usual comfort amenities should be present.

In many cases, the information inputs will simply be read aloud by the Exercise Controller. This permits the Exercise Controller to directly monitor the results of each input delivery, which may help to direct the learning in the debriefing which will follow the actual Exercise. However, if the team is being trained in an actual Command Center, a unique opportunity exists for a tremendously increased level of realism for the participants. A control cell9 is a separate room, located somewhere near the Command Center, equipped with telephones, a computer, a fax machine, and possibly, a two-way radio. In this room, subordinate Exercise Controllers, under the direction of the Chief Controller, will deliver the inputs to participants as dictated by the Exercise script, using the previously mentioned communications devices. To illustrate, if the team has not yet ordered the establishment of a Family Information Center in the facility, Security may report, by two-way radio, that there are upset family members creating a disruption in the Emergency Department. The team may receive a telephone call from the Fire Department or Police Department or a fax containing instructions from the Public Health Department. In this manner, for the participants, information will appear to be flowing in an extremely realistic manner.

Immediately following the conclusion of the Exercise script, the team or teams will be debriefed. Two types of debriefing are possible. These include an informal debriefing, conducted immediately following the conclusion of the Exercise, while the participants are still under Exercise stress, often called a “hot-wash” debriefing, or a more formal debriefing, conducted some time later or even by questionnaire. It is the experience of the author that the most useful of these is the “hot-wash” type of event. A debriefing can be an intimidating and even, in some organizations, a political event. Participants, while still under Exercise stress, are much more likely to speak frankly. They will tell you about things that went wrong, which would never occur following sober, second thought! In more formal debriefings, participants are likely to be much more measured and cautious in their responses, even with an assurance that the contents of the debriefing will remain confidential. With questionnaires, their principal value is that those who take the time to complete and return them will include not only problems identified, but also solutions and suggestions for improvement. The problem with questionnaires is that, typically, under 20 percent of the completed questionnaires will ever be returned to the Emergency Manager.

It is also useful to debrief all of the Exercise Controllers separately as a group. This will provide useful information on observations at individual locations during the Exercise, information which might not have been readily apparent to the Emergency Manager. This is also useful from a quality improvement perspective for the Exercise itself. Did unexpected deviations from the Exercise script or even outright Exercise errors occur? How were they corrected? What can be done to prevent their recurrence? Were there ways in which the Exercise itself could be improved? This type of debriefing not only improves and strengthens each Exercise script, but also helps to build the experience and the level of collaboration among the members of the team staging the Exercise. In this manner, the Emergency Manager can not only teach and train the Command Center Team, but will also develop an experience pool among those helping to stage the Exercise, perhaps even leading to an enhanced Emergency Preparedness Committee for the facility.

Functional Exercises

Functional Exercises may be used to develop or refresh mechanical skills which are performed only infrequently, but which may be essential during the facility’s response to an emergency. The purpose of functional Exercises is to discreetly test those individual elements of the response which are essential to success, but seldom practiced. They help to train the staff and can also provide the Emergency Manager with essential information required for the growth and continuous improvement of the Emergency Response Plan. What follows are a few examples of functional Exercises; in reality, any emergency-related procedure can be tested, and the list is limited only by the imagination of the Emergency Manager.

Testing Emergency Staff Recall

If off-duty staff were to be required at the facility in order to cope with an emergency, how would they be recalled? Does the facility actually have adequate recall information or a system for doing so? How up to date is the information? How effective is the recall system? These are all questions which typically haunt many Emergency Managers operating in healthcare facilities. This information is crucial, because without adequate staff, the best Emergency Response Plan in the world will not work! Such systems need to be tested, and this needs to occur on a regular basis.

For decades, hospitals have relied upon an old tool called a telephone fan-out list to recall staff during a crisis. There are several flaws with this approach. In the first place, for healthcare facilities in an urban setting, telephone fan-out lists which are not scrupulously maintained and tested (at minimum every six months) will go out of date by approximately 20 percent, per year! Staff come and go, and they change positions. Staff move and change telephone numbers. The Personnel Department or the Supervisor may be notified by staff members of these changes, as per policy, but somehow this information never quite finds its way from the personnel file to the emergency telephone fan-out list. The result is a list full of people who no longer work there, don’t have the same telephone number that is listed, or have completely different responsibilities and is missing people who have joined the organization, but for whom you have no method of contact!

Such fan-out lists are typically an “all or nothing” tool. The list either calls the entire staff to work or they get no one. Such lists typically use a “tree”-type configuration. Those activating the list call the Supervisor or manager of every service and notify them. They, in turn, are expected to call all of their staff and ask them to report for work, and then report their results back to those who originated the call-out. If a Supervisor or manager cannot be reached, there is a potential that none of their subordinates will be contacted either. There is also a possibility that the required staff telephone list will inadvertently be left at work. In either case, the potential exists for entire services and departments within a facility to remain “dark” during a call-out.10 The other distinct possibility is that you will succeed in calling out three times as many people as you actually require or people for whom you have no work!

Also problematic in this process are the changes in technology which have occurred over the past several decades. These include the widespread use of mobile telephones and tablet devices. They also include features such as “Caller ID,” and the fact the people are increasingly mobile and often have a vacation property in addition to their principal residence. The result is that many people no longer have a single telephone number; they may have several, all of which are active, and any of which they might be at when you require them in an emergency. If you need to reach them, you may need to call all of those numbers! When fan-out lists were created, telephones were static devices; you were either near them, or you were unavailable. This is now seldom the case, although the recall methodology has only rarely changed to adjust for this. Envision a masscasualty incident at a hospital; staff recall has been activated. Three ER nurses, all off-duty, are sitting at a planned dinner outing in a restaurant which is less than a mile from the hospital. All have mobile telephones, but because the fan-out procedure is calling only their home telephone number, three urgently needed resources are unavailable for recall. This is also true of the stereotypical doctors on the golf course, and so on.

More troubling is the problem of Caller ID. As working in healthcare becomes more and more demanding, staff members are opting out of recalls. In many facilities, staff are asked to work more overtime hours, instead of hiring additional staff. The economic reasons for this are obvious and understandable, but it reaches a point where staff members may have worked all of the overtime that they want, and thus begin using the Caller ID feature on their telephone to simply screen incoming calls. When they see the facility’s number on the Caller ID, they simply do not answer the telephone, and another resource is lost. In any case, without regular and systematic testing of the system, such problems as described here will be neither identified nor corrected until a crisis actually occurs!!! Without someone, or a group of people, periodically sitting down and actually calling every number on the list and documenting the results, then following up on the failures to connect, the Emergency Manager will never have a staff call-out tool upon which any confidence can be placed.

Assembly of the Command Center

In the vast majority of healthcare facilities, the facility Command Center is not a purpose-built resource. Such tools tend to exist only in a very small number of very large and resource-rich facilities which can afford the space and resources required. Most often, the facility Command Center will be a boardroom or a classroom which is converted to this use when required, usually from equipment which is stored in the room under lock and key or on carts which are securely stored elsewhere.

Figure 1.2 The assembly and testing of the Command Center is essential to preparedness

In such cases, workstations, resources, and equipment for individual members of the Command team will require assembly and testing. These will even include a telephone network, a computer network with all of the required peripherals; all of this equipment is typically multiuse, due to economic considerations. This assembly needs to occur quickly and correctly, even in the middle of the night!11

The vast majority of Command Center staff will not be computer or telephone system experts, nor will they immediately understand the mechanics of converting the workspace. Many of these individuals will rarely even know where the equipment which they are using comes from or how to get it. It is a simple truth that the person in charge of the Command Center is almost never the same person who knows how to change the toner cartridge on the printer! That does not mean that they are not the most likely person to have to perform these functions in the middle of a crisis at 2 a.m.! These individuals will require training, and refresher training, and the problems of assembling the Command Center at short notice will need to be identified and addressed.

As previously stated, “adult learners learn best by doing,” and so, the best way of achieving all of these objectives is to simply bring everyone together periodically (every six months is recommended) and have them actually assemble the Command Center from kit form, and then put it away when they are done. This will permit the identification and resolution of any problems before the crisis actually occurs. Such testing can actually even be incorporated into a tabletop Exercise for Command Center staff; after all, this is what is likely to happen in a real emergency, and so, contributes directly to the realism of the experience.

Tactical Exercise Without Troops (TEWT)

There is a list of facilities which do not exist on a daily basis within most healthcare facilities, but which are likely to be required during any major emergency. These include a designated space in which off-duty staff will report, be briefed, and be assigned to duties as required. This space is also where staff will return for reassignment, when their existing assignment concludes and where all staff timekeeping will occur. Almost no staff member is likely to end up working in their unit of origin during a crisis. The staff staging area, staffed by Administration, Human Resources, and Payroll staff, fills such a function, and the facility will fall under the jurisdiction of the logistics function, in most Command and Control models.

Also included is a space in which the members of the media can be placed and provided with information, usually called a Media Center. They are sequestered in this location and permitted to do their jobs, without disrupting the business of the organization or violating patient privacy. It is here that media conferences and interviews will be conducted and media releases and background information will be available. Such facilities are typically staffed by corporate communications or a similar function, supported by Security, and they fall under the jurisdiction of the public information function in most Command and Control models.

Also required is an area in which the families of victims can be sequestered, away from public scrutiny, to await news on their loved ones. It is from this family information center that the identification of unidentified victims is likely to occur. Here both good news and bad news will be delivered by individuals with experience at this special skill. Family reunification can also occur at this location. Such facilities are typically staffed by Social Services, Pastoral Care, and hospital volunteers and fall under the jurisdiction of the planning function in most Command and Control models.

Other areas which may be required include areas for the triage of incoming patients, temporary treatment areas to prevent the overwhelming of the ER, temporary treatment areas, including improvised critical care expansion spaces, and spaces for the specific use of decontaminating any patients exposed to hazardous or radioactive materials. This list is by no means comprehensive; there are probably many temporary facilities required, but these are the most common.

The Tactical Exercise Without Troops (TEWT) has its origins in the military, where typically before a war-game Exercise, military officers would gather together, walking across the “battlefield” and identifying locations for fixed facilities, and the resources and supply chains required to support them.12 A similar function is possible within any healthcare facility, with the Emergency Manager, and, ideally, the Emergency Preparedness Committee, walking through the facility and identifying both primary and backup locations for the placement of all temporary disaster resources, identifying the “owners” of these locations, and securing permission for their use and instructions for how to access them, including outside of normal business hours. The resources required for each type of facility are then identified and sourced, and the supply chains to support them are formalized. Once all of this is in place, these resources may be formally incorporated into the facility’s Emergency Response Plan. It is useful to repeat this Exercise at least annually, as healthcare facilities tend to grow organically, and a space which seemed “perfect” during the last TEWT Exercise may have radically changed, due to the legitimate needs of its daily occupants.

Assembly of Decontamination Equipment

In modern society, every hospital should have some provision in place for the safe decontamination of patients who have been exposed to radioactive or other hazardous materials. While the facility may not be in a war zone, or in an area perceived as being particularly susceptible to terrorist activity, it should always be borne in mind that, in most of the developed world, one heavy truck in 10 and virtually all freight trains are carrying some form of hazardous materials. As a result, the possibility of receiving contaminated patients is real, and has real potential for totally disrupting the operations of the facility. As a result, every acute care hospital should have a plan and resources for conducting decontamination of incoming patients.

Any assumption that all patients will be decontaminated prior to transport or that the local fire service will arrive to perform decontamination for the hospital is likely to be largely false hope; many patients arrive by means other than EMS, with little or no decontamination, and the vast majority of fire services, with the exception of very large ones, often have little or no equipment or training in decontamination procedures. Each healthcare facility will need to make its own arrangements for decontamination, either through training and equipping their own staff or by “contracting out” to a commercial service provider, if one is available.13 The lowest cost option is usually the training and equipment of the facility’s own staff. In the United States, the Federal Emergency Management Agency actually provides online and in-person courses for the training of healthcare staff to manage contaminated patients.

Such skills will typically be used on a relatively infrequent basis. As a result, those staff assigned to the various decontamination roles will benefit greatly from a period Exercise in which they assemble the decontamination area from a kit, “don and doff” personal protective equipment, and “decontaminate” on or several “patients,” suffering from a variety of exposures. The ability to assemble equipment, dress safely, and begin decontamination quickly and effectively is essential to success, and it may even ensure that the facility does not have to close its doors due to potential hazardous material contamination.

Triage is a formal process for sorting patients according to clinical severity, in order to provide appropriate levels and order of access to limited clinical resources.14 This usually occurs in most daily Emergency Department operations, but assumes greatly increased importance in any major emergency. Whereas on a daily basis, it is a relatively slow process, with patients assessed one at a time by a single nurse determining the order of access to the Emergency Department, in a mass-casualty situation it is more likely to be algorithm based, conducted by several nurses, attempting to “sieve” and redirect large numbers of patients arriving simultaneously, either to the Emergency Department or, for the less serious cases, to alternate treatment areas. Moreover, subsequent retriage may be required, in order to provide order of access to diagnostic resources, operating theaters, in-patient beds, and even critical care beds.

Figure 1.3 Triage Exercises practice: an essential skill

In such a state of potential confusion, the safe and effective triage of incoming patients can become elevated to almost an art form. While most Emergency Departments have no shortage of nurses who can perform daily triage, this more elevated form of triage requires its own special spaces, additional training, and repeated practice, in order to sharpen assessment skills and ensure that, when actually needed, all efforts are performed correctly, with all patients receiving appropriate care, quickly, safely, and efficiently. Regular opportunities to practice these skills, in the form of simple, low-cost, functional Exercises are essential to achieving these objectives, and such opportunities should be provided to predesignated staff members on at least a semiannual basis.

Evacuation of the Facility

One of the greatest challenges ever to face any healthcare facility is likely to be the safe and effective evacuation of its patients, staff, and visitors. This can occur through a variety of circumstances and may require a rapid removal, such as with a fire, or may be a more controlled response, such as with a prolonged utility failure. While it can be argued that the populations of healthcare facilities are typically the most vulnerable population within any community, there has, historically, been surprisingly little activity at actual evacuation.

Figure 1.4 In evacuation Exercises, much can be learned from moving a single, simulated sample patient

In a research conducted in Canada in 2000, for example, it became apparent that the vast majority of acute care hospitals of all sizes and locations had completely unrealistic expectations of how long it would actually take staff to evacuate the facility. This is not particularly surprising, since the majority had never even attempted to evacuate, even as an Exercise;15 in fact, less than one-third of the acute care hospitals in the entire country had ever tested their ability to evacuate, and only 8 percent had tested their ability to receive evacuees from another healthcare facility. Such results are not exclusive to Canada, and are, in fact, much more common than we would wish to believe. An increase in interest by Accreditation bodies, and by legislators, is slowly changing this reality in most countries.

The most common reasons cited for a lack of evacuation practice were the safety of both patients and staff and the disruption of daily business. In fact, these arguments have some validity; it is unsafe to begin moving actual patients for the purpose of an Exercise, and it would be unforgiveable if a patient or staff member were actually injured during training. That being said, it is quite possible to generate a great deal of useful information about the evacuation of the facility without putting a single patient or staff member at risk. The challenge is to develop the information without actually evacuating.

The patients normally housed within a typical healthcare facility can be differentiated by three common factors: clinical acuity, degree of mobility, and degree of supervision required. It is entirely possible to develop an evacuation “benchmarking” Exercise, using these characteristics. The Emergency Manager has the potential to simulate a high-range and low-range patient for each of these three characteristics, with a handful of additional simulations for other patient types with special needs, including incubators, bariatric patients, and perhaps, intensive care patients.

These patients can then be placed in the most distant and inaccessible location of the facility, and then moved, one at a time, to the designated point of egress. In each case, the amount of time required and the amount of staff resources required to perform the movement would be recorded. Each simulated patient would be moved through the process twice, the first time, using elevators to simulate a nonurgent, controlled evacuation, and the second, with no elevators used, simulating a “flight to safety” scenario, such as a major fire.

Simultaneously, a telephone poll could be conducted, asking neighboring facilities how many of the sending facility’s patients could be accommodated, if a real evacuation were occurring. The facility would also poll potential transportation providers, such as Emergency Medical Services, private ambulance companies, private patient transportation services, and bus companies, in order to determine how many of each type of vehicle would be available at that moment and what the estimated time would be for a round trip to and from each potential receiving facility. Most facilities estimate time of evacuation to the “front lawn” of the facility; this represents a much more comprehensive picture of what evacuation would look like, were it to actually occur.

By placing these patients in the furthest and most inaccessible location in the facility, the timings generated represent an absolutely “worst case” scenario. By then conducting a census of the entire facility, using the characteristic classifications used in the Exercise, a much more realistic picture is generated of how much time and resources would be required to successfully evacuate the facility in both types of scenarios. They also represent a benchmark, by which future evacuation tests may be measured, permitting the Emergency Manager to monitor progress and to adjust for and justify the acquisition of resources to address any identified shortfalls. Such a process is extremely useful and should occur regularly, probably on an annual basis.

Fullscale Exercises

fullscale Exercises have been widely believed by many to be the only “real” type of Exercise, and this belief has resulted in a good deal of the general resistance by healthcare administrators to many proposals to conduct an Exercise in a healthcare facility. Many administrators believe that such Exercises are complicated, expensive, occupy a great deal of staff time, and have the potential to interfere with the core business of the facility or the organization. In the case of fullscale Exercises, most of these beliefs are somewhat accurate, at least for this type of Exercise.

The fullscale Exercise involves the use of dozens, perhaps, in some cases, hundreds, of people. Performed properly, they will involve corps of simulated patients, often community volunteers, members of service clubs, or students. These will require some degree of casualty makeup and programming as to their signs, symptoms, and expected behaviors. The Exercise will also require a large group of staff members, in addition to those who are currently on duty caring for the actual patients of the hospital. Most of these will be on overtime pay, since the staff who are already on duty cannot be taken away from the real patients for an Exercise. The Emergency Manager needs to educate the administrator to the fact that there are many useful and cost-effective options for Exercises and that the proper place for the fullscale Exercise in an effective healthcare Emergency Management program occurs only occasionally, and then only for confirmation.

A fullscale Exercise will require less storytelling, and only a minimal number of inputs, usually only to start and finish the Exercise. In a fullscale Exercise conducted in a healthcare setting, the patients themselves become the inputs. These patients will need to be decontaminated if necessary, assessed and triaged, assigned to the appropriate treatment area, registered, recorded the initial assessment and history, diagnosed and treated, assigned to diagnostic/treatment resources, and then moved through the system to a point which is predetermined by the Emergency Manager when the Exercise is created. As each patient reaches the point of conclusion, the Exercise is over for that patient. When there are no more patients to be processed through the system, the Exercise concludes.

The Exercise itself can involve any variety of scenarios, with an intent of testing specific aspects of the emergency response mechanism. It may be conducted in isolation, or it may be a part of a larger Exercise conducted by one of the emergency services or the community in which the facility is located. To illustrate, the community elects to conduct their annual emergency response Exercise with a scenario of a school bus accident or a plane crash. As the Exercise progresses, the “patients” are located, extricated, triaged, and treated at the scene. They are finally transported from the incident site according to triage priority, and, as they begin to arrive at the local hospital, that aspect of the Exercise begins. The emergency services will have their own objectives to accomplish in their portion of the Exercise, while the healthcare facility will have a separate, but equally important series of objectives and processes to test. Both organizations cooperate, and both draw the benefits that they need from the process. Similarly, when acting alone, the healthcare facility will probably simply imagine an incident, such as the bus or plane crash, and the Exercise will begin as the “patients” begin to arrive at their doorstep.

Such Exercises are elaborate and complex, and most good ones require literally months of planning. An appropriate first step, as with any type of Exercise, is the setting of objectives and the determination of precisely how these objectives will be met, along with a definition of precisely what series of steps constitutes a pass or fail for each objective. Next, a scenario should be chosen and researched, in detail, in order to ensure the accuracy of its presentation. The time of occurrence and day of occurrence are also important, as these will, to some extent, determine the amount of impact on the real treatment resources of the facility; conducting the Exercise on a Sunday morning will impact less real patients, but will require the payment of more overtime to staff. Conducting the same Exercise on a Wednesday morning means more staff will be in the facility, but will also likely pose significant interference in the treatment of real patients.

Ideally, the facility’s Emergency Response Plan should be activated twice in each calendar year, at minimum. It is not mandatory that every Exercise feature a mass-casualty incident scenario; any type of emergency event may be chosen, and all should be tested periodically. It should be noted here that any Exercise is intended as a substitute for real learning experiences. In most Accreditation standards, this fact is recognized. In the Joint Commission Standards,16 for example, any facility which has a real major emergency event within a calendar year may substitute this for a required emergency Exercise, providing that it has been debriefed, documented, studied, and used to drive improvements to the Emergency Response Plan.

The development of such an Exercise is a massive effort, and doing so requires a team to support the Emergency Manager. The best Emergency Manager in the world cannot possibly create, develop, stage, debrief, and report a good fullscale Exercise alone. An Exercise Planning Committee will need to be created. In a healthcare setting, this should include a representative from every department which will be affected by the Exercise. The Emergency Manager may also wish to include representatives from local emergency services and/or the municipal Emergency Manager, in an advisory capacity. Choose the Committee Members carefully; this will be a months-long commitment, at least on a part-time basis, and a significant amount of additional work from everyone involved. Common sense and an understanding of human behavior indicate that the Emergency Manager is likely to get more effort and more useful result out of a Committee Member who actually wants to be there.

As previously stated, Project Management skills are a useful tool in the development of any Exercise, and this is particularly true in the case of a fullscale Exercise. Most Exercises of this type begin preparation six months to a year in advance of their actual occurrence. They require a long list of individual projects, which can be treated as steps to the completion of a much larger project. Some of these projects will be independent, but many will be intrinsically connected to other projects and cannot begin until these are completed. To illustrate, a group assigned to begin the design of an “accident” area cannot begin to do so until the area has been selected, permission obtained for its use, the type of accident determined, the use of the “school bus” obtained, and so on. The entire Exercise can and should be the subject of a formal project plan, created by the Emergency Manager. Each subordinate step must be identified, the interdependencies of the steps determined (e.g., we can’t obtain casualty makeup until the list of injured “patients” is developed), and timelines identified.

These subprojects need to be placed in chronological order and must follow a logical flow. Some projects will be more essential than others to the successful development and staging of the Exercise, and the Emergency Manager will benefit from the plotting of all of these measures on a linear chart for tracking and control purposes. There are several approaches to this charting which will work, including Gantt charts17 and “fishbone” diagrams,18 also known as “Ishikawa” or “cause and effect” diagrams, the use of which can be learned in the most basic of Project Management training. Once all Exercise development measures and subprojects have been plotted, and the interdependencies identified, the Emergency Manager should be able to identify a “critical path” to project completion.

Another useful approach is to employ the use of step-by-step “checklists,” as per the “standardized work”19 approach of both Lean Healthcare and Six Sigma, for both subordinate projects and the main project, and a method of providing consistent work and reporting, and for measurement of progress, for use by the Emergency Manager and all subordinate Committee Members who are assigned projects. Subprojects can then be assigned to individuals or groups, along with completion dates, according to priorities for completion and availability of appropriate resources and skill sets, timelines for completion set, and then the project and each subproject or step can be dynamically monitored for completion.

To illustrate, one work group might be assigned to identify and obtain the use of physical areas required in order to stage the Exercise. Each of these will require identification of each separate location, determining “ownership” of the space, negotiating conditions for its use, obtaining permission for its use, determining the resource requirements for the intended use, and sourcing these. Finally, the spaces selected will need to be presented to those in another group who will be planning actual Exercise play and need to know what resources they have at their disposal, a process which cannot begin in earnest until the areas are identified. In this case, the specific areas required, which will vary according to the scale and type of Exercise being planned, might include, but are not necessarily limited to:

Exercise Area

Accident Area

Triage Area

Treatment Area(s)

Debriefing Area

Changing/Clean-Up Area for “Patients”

Male

Female

Casualty Makeup Area

Exercise Control Area

Exercise Briefing/Debriefing Area Observation Area

Each of these will need to be negotiated for and obtained individually, usually well in advance of the actual date that the Exercise is to be staged.

Another framework element which can and should also be used for Exercise planning is one which is already quite familiar to the Emergency Manager, the facility’s Command and Control model. Just as it is used to manage an emergency, remember that the resolution of the emergency is also a project and that the same skills areas and division of responsibilities will prove useful. To illustrate, while the example used is not exhaustive, in a facility which uses ICS, IMS, HECCS, or HEICS, the Incident Manager/project manager would be the Emergency Manager, with separate groups developing:

Safety (site, participants, actual patients, emergency procedures) Liaison (with senior management and outside agencies, thank-you letters)

Public Information (staff updates, media management) Operations (Exercise Control Group)

Planning (Exercise script development, controller/observer briefing, debriefing)

Logistics (human resources, sites, materials management, support resources)

Finance (budget, cost to date, etc.)

By managing the development and staging of the fullscale Exercise in this manner, the control of an exceedingly large project can be maintained and the project itself can be completed successfully.

As with all Exercises, the completed Exercise will require the debriefing of all participants (including the simulated patients), Exercise Controllers, Committee Members, and observers, in order to identify all of the problems identified and other successes of the Exercise, as well as any problems in script development and Exercise play. This should include both the “hot-wash” approach previously described, with copious notes being taken, and the use of debriefing questionnaires. The group size in a fullscale Exercise is far too large to ensure the accurate capture of the critical performance information needed by the Emergency Manager in any other way.

At the completion of the Exercise, a clean-up team will be required to restore each location used for Exercise purposes to its original condition. A similar team will also be required to clean and restore those other resources borrowed for Exercise purposes to their original condition. Once these measures are completed, the resources and physical spaces will be returned to their original “owners,” in at least as good a condition as they were received in. The Emergency Manager should make a point of sending a personal “thank-you” note to each of these individuals; a Department Head who feels that their efforts are appreciated and valued is far more likely to provide cooperation for future Exercise efforts! Similar “thank-you” letters should be provided to the affected Department Heads, all Exercise participants, and Committee Members (and to their normal Supervisors), and to any municipal or emergency services which participated in the project.

Finally, the Emergency Manager will collate the findings of the de briefings and will use these to create a formal After Exercise Report. This report will be provided to the senior management of the organization and will outline the scenario nature of the Exercise, what was tested (and what was not), the strengths and weaknesses identified, opportunities for improvement, and next steps. The report should also acknowledge and thank all of the Committee Members. This report should be provided to all members of the Senior Management Team, with the Emergency Manager prepared to answer any questions which may arise from this review. A copy should also remain on file to support any future Accreditation submissions or any need indicated by the facility’s Legal and Risk Management Departments.

Exercise Control

On the day of occurrence, the Exercise will be run by a group called the Exercise Control Group. This group consists of a Chief Exercise Controller, who coordinates the overall running of the Exercise and assigns tasks to subordinates, based upon the Exercise script, and subordinate Exercise Controllers, who will perform tasks which manage the “flow” of the Exercise. Each of these individuals should be readily identifiable, usually by means of colored vests or tabards, and each should ideally be in two-way radio contact with the Chief Controller and their colleagues on a private frequency (not audible to participants) throughout the Exercise. Also often present at any Exercise are a group of observers, often from other facilities or outside agencies, and these should also be readily identifiable by means of a different colored vest or tabard, or some other visual marker.

Participants should be briefed in advance of the start of the Exercise regarding the “rules” of Exercise play, what is permitted, and what is not. They should understand the boundaries of the Exercise area, what is simulated, and what is real. They should also be informed on how to identify Exercise Controllers and observers and should be informed that they may refer to an Exercise Controller if they have a problem, but that for the purpose of the Exercise, the observers should be regarded as “invisible.”

Exercise Safety

Safety is of paramount importance during any Exercise. There is never a reasonable excuse for any Exercise participant, staff member, or volunteer to become injured during Exercise play. As a result, the Exercise Safety Officer and any subordinate staff should be charged with carefully preinspecting every element of space being used for the Exercise, in order to identify and remedy any potential safety hazards which may be present. During actual Exercise play, this group should be patrolling the entire Exercise site, with a clearly understood mandate that they have the authority to immediately halt Exercise play at any time when a potential hazard is identified.