Introduction

Currency risk arises from the fluctuations in exchange rates between currencies. Currency trading is the largest trading market with an estimated $3 to $5 trillion being exchanged on a daily basis. Although exchange rate fluctuations are somewhat controlled by central banks, the control has at best a dampening effect and is a secondary factor. Thus, we see wild variations in exchange rates and exchange rate crises such as the Thai Baht crisis in the late 1990s.

Currency risk arises in many different forms. It can be transactional—such as repatriating sales achieved in a foreign currency or paying expenses in a foreign currency, or it can be translational—adjustments to the financial statements based on accounting for foreign currency transactions, or it can be strategic—such as changes in relative price competitiveness to a competitor whose cost structure is based in a different currency.

Relatively few companies will hedge translational exposure. Although it affects the earnings of a company for a cycle, it is not related to cash flows. Most analysts understand the effects of translational exposure and thus are not concerned by the effects on earnings. Most analysts consider that attempting to hedge translational exposure is actually just introducing costs and economic exposure to deal with the cosmetic effects on earnings.

Currency risk affects virtually all companies of a certain size. This is irrespective if a company even has foreign operations or sales. The world operates on a global scale and the relative competitiveness of a company is based in large part on their cost base, which in turn is directly affected by exchange rates. Entire countries, and by extension, entire industries can see their relative competitiveness change quickly as exchange rates tend to be one of the more volatile financial variables. With a robust currency risk management plan, companies can find their competiveness being severely compromised in a hurry.

The markets and techniques for currency risk management are highly developed and liquid. The range of products available for managing currency risk is probably the broadest of any of the financial markets. Due to the high liquidity, currency risk management is also one of the most cost-effective markets to trade in. However, with the breadth of products comes a cost; which is, the extensive range of products implies a bigger learning curve for those companies that want to go beyond the basic forward, swap, and option type products.

Currency Fundamentals

Conceptually, exchange rates are driven by supply and demand just like any other financial product. In large part, this is true in reality, but there are other important forces at work as well. As with interest rates, exchange rates are an important part of a country’s domestic economic management policy. Exchange rates affect inflation rates, and also significantly affect employment as a strong currency will make a country’s goods less competitive in the global marketplace. If a country’s currency becomes too strong, their products become less competitive, which means decreased sales and thus decreased GDP and decreased employment. For these key reasons, central banks keep a keen eye on exchange rate moves and are not shy about using a variety of means to support their currency within a desired trading level relative to other currencies.

For most of the major developed countries, the currency is allowed to “float” or trade freely. Other countries however keep their currency “fixed” within a tight band that is generally pegged to the U.S. dollar. However, even for countries that technically have a free-floating currency, government actions will play a major role in determining the exchange rate or the rate of change of the currency.

Trading levels between countries obviously affect the supply and demand for currencies. Also for those countries that derive significant income from a commodity, the currency can become dependent on that commodity and thus we get the label of a Petro-currency.

Countries through their central banks can, and do, impose a variety of techniques in an attempt to maintain their currency within a desired trading band. The most straightforward is having the Central Bank of the country trade significant amounts of their currency in the open trading markets. Another indirect method that affects the currency is by having the Central Bank adjust interest rates. There is a direct link between interest rates and exchange rates. In extreme cases, countries can affect their exchange rates through currency controls such as limiting foreign currency transactions or even regulating the exchange rate. Both currency controls and regulated exchange rates generally cause extremely distorted markets where official exchange rates bear little to no relationship to actual relative value. When this occurs, black markets for the currency generally arise. In such cases, there will be a demand for “hard currency” from a major developed country that does not have such currency controls.

An example of the demand for “hard currency” was the situation in Russia in the early 1990s as liberalization just started and Western countries were just starting to set up operations there. The Russian Ruble was severely mispriced in the official Russian exchange markets, and thus a black-market exchange market opened up. Many businesses, such as Pizza Hut, would run dual operations; one operation for locals who had Rubles to spend, and a second, and separate set of operations for those who had “hard currency” such as U.S. dollars. While illegal black markets are an option for some risk-loving tourists, they are not a viable alternative for corporations.

There are two central economic relationships that determine exchange rates. The first is Purchasing Power Parity, while the second is Interest Rate Parity. Over the long term, both principles hold quite strongly although there can be short-term deviations for a variety of reasons, most generally trade imbalances, or perhaps even the actions of currency speculators acting on forecasts for relative economic performance of a given country.

Purchasing Power Parity simply says that equivalent goods should cost the same in different countries and in different currencies after accounting for the exchange rate. For instance, if something cost 3 units of currency A, and the exchange rate is 2 units of currency B per unit of currency A, then the cost of the item should be 6 units denominated in currency B.

The Big Mac Index

Perhaps the most well-known expression of Purchasing Power Parity is the Big Mac Index that was created by the Economist weekly newspaper. The Big Mac Index tracks the cost of a McDonald’s Big Mac burger in a variety of different currencies around the world. If Purchasing Power Parity holds, then the Big Mac hamburger, which is as close as one can get to a completely fungible global consumer good, should have the same cost after accounting for the exchange rate. Of course, the conversion is not perfect, in part because McDonald’s does not change the prices of its hamburgers on a daily basis to track currency moves. However, the Big Mac Index does give a relatively accurate, yet quirky, analysis of which currencies are over- or under-valued. It needs to be noted that Purchasing Power Parity is not perfect as taxes, transaction costs, and a variety of other factors will affect the exchange rate.

The second key currency relationship is Interest Rate Parity. Interest Rate Parity states that investing for a set period of time in one period at a fixed interest rate in one currency should provide the same investment outcome as investing in a different currency, and at that second currency’s associated fixed interest rate, for the same period of time. In other words, forward exchange rates can be completely explained by interest rate differentials.

Consider the following two-currency example:

1-year interest rate in currency A is 5 percent

1-year interest rate in currency B is 8 percent

Spot exchange rate is 1 unit of currency A = 2 units of currency B

If one has 100 units of currency A to invest, then at the end of 1 year they will have:

100A × (1+interest rate) = 100 × (1 + 0.05) = 105 units of A

Alternatively, the investor could exchange their 100 units of currency A at the spot exchange rate and receive 200 units of currency B to invest. Investing the 200 units of currency B for 1 year will provide investment proceeds at the end of the year of:

200B × (1 + 0.08) = 216 units of B

Thus, the forward exchange rate must be by Interest Rate Parity:

105 A = 216 B → 1A = 2.0571 B

In this case, currency B has depreciated (it now takes more units of currency B to buy 1 unit of currency A). Note that if the 1-year forward exchange rate quoted in the market is anything other than 1A equals 2.0571B, then there will be an arbitrage opportunity and speculators will trade in the currency markets (and the associated money markets) until the Interest Rate Parity relationship holds.1

Interest Rate Parity provides a direct connection between interest rates in two countries and the respective forward exchange rates in the two countries. Spot rates, forward rates, and even the respective interest rates will adjust to ensure that Interest Rate Parity holds within a tight band. Therefore, while Purchasing Power Parity holds approximately, Interest Rate Parity is a rule that is forced to hold true due to the actions of arbitrage traders.

Currency Hedging with Operational Strategies

The currency markets for trading and hedging are very active and the number of ways to hedge currency risk with derivatives are many. However, before examining some of the specific currency hedging tools, it is useful to discuss some operational style hedges.

The most basic operational style hedge is to build facilities in the foreign country in which one has operations. Thus a U.S. company that has sales in continental Europe and is concerned about the exchange rate risk between the euro and the U.S. dollar can build a plant in Europe to mitigate the exchange rate risk. Obviously, there are a host of operational and marketing advantages and disadvantages apart from the currency risk management aspects of taking such an action. There will be a variety of expenses, as well as savings associated with such a tactic, and operational advantages and disadvantages as well.

Hedging currency exposure through developing foreign operations such as building foreign manufacturing facilities is obviously a very blunt way of hedging currency risk. One advantage is that by building foreign facilities, companies will increase their exposure in that country and likely decrease their political exposure. Generally, countries do not want to put local jobs at risk by threatening sanctions, tariffs, or ruinous taxes on a foreign company operating domestically. Countering that point is the risk of expropriation. These concerns are not currency risk per se, but are illustrative of how currency risk management can involve so much more than managing the risk of specific transactions.

From a currency risk management viewpoint, having facilities in a foreign country significantly reduces currency risk as expenses will now also be in the foreign currency. Thus if the foreign currency depreciates, then that implies that the manufacturing expenses will also depreciate on a relative basis. To the extent that expenses and sales are related, there will be a natural hedge.

A second operational hedge is to set up the financing in the foreign currency. By taking on debt in a foreign currency, one now has obligations in a foreign currency that help to offset the cash inflows in that currency, thus reducing the currency risk. A related benefit of financing in a foreign currency is that one may also be reducing the sovereign risk of an expropriation or of currency controls. If the cash outflows are restricted, then the company may be able to justify not making payments on debt denominated in the currency of that country and debt that is held by investors in that country.

A third operational hedge that is used in business-to-business transactions is simply to sell globally in your own domestic currency. This essentially puts the currency risk on the foreign buyer. Obviously this has disadvantages as it may negatively affect sales, but in countries without a convertible currency, or one that cannot be easily hedged, it may be the only method to reduce or eliminate currency risk.

Several companies have taken currency risk and turned it into a marketing advantage by giving business-to-business clients the choice of currency in which they may pay. If a company has strong currency risk management capabilities, this is one method that they can use it for competitive advantage. By giving the customer the choice of currency in which to pay, an organization is essentially taking on the currency risk management for their customer. In many cases, this may be a service that the customer would be happy to pay for, or at least give preferential sales considerations to.

Operational strategies such as building a manufacturing capability in a foreign country tend to be very blunt long-term tactics for currency risk management. The use of traded derivatives is better suited for specific situations and is of course easier and more flexible in nature.

Currency Risk Management with Derivatives

As with all other types of financial risk, there are two main types of instruments for managing currency risk: forward type strategies and option type strategies. Again, as previously discussed, forward type strategies lock in the price at which the transaction will occur, while option type strategies allow one to asymmetrically manage good risk versus bad risk.

There are a couple of unique challenges when developing hedging strategies for currency risk. The first challenge is that currency risks are arising on a daily basis as the company may have an uneven and random stream of both cash inflows as well as cash outflows in a variety of different currencies. The fact that currency transactions occur on a more frequent basis than, for example, interest rate risks tied to a financing which tend to occur less frequently, implies that it is more complicated to calculate the exact amount of exposure at any given point in time. Additionally, there is the aspect of cash inflows, as well as outflows which adds to this challenge. The exact outstanding net balance of exposures to a given currency can be a constantly changing dynamic. At any point in time, a company could have either a net long exposure to a foreign currency or a net short exposure to a given currency.

The second difficulty of currency hedging is that there are likely to be several currencies that the organization is exposed to. These currencies will have varying correlations. At any given point in time, the domestic currency could be strengthening against one foreign currency and depreciating against a second currency. The currency exposures to the two foreign currencies could be offsetting at any given point in time. Hedging both of them simultaneously without taking into account the correlation between the currencies could in fact lead to a case of over-hedging, where the net effect is that the company, based on its hedging activities, has not neutralized its exposure to changes in the exchange rate, but actually magnified it. The difficulties of precisely hedging currency risk have given rise to the use of exotic options for managing currency risk. Exotic options will be discussed later in this section.

For specific foreign currency transactions, the most straightforward way to manage is with a forward transaction or an option transaction specifically tied to the size and timing of the transaction. For a company with relatively few foreign exchange transactions, this is probably the simplest and most effective method to manage currency risk. Managing currency risk on a transaction-by-transaction basis, however, does not deal with the issue of the strategic aspect of currency risk, nor is it practical for a company that has a large number of ongoing foreign currency transactions.

In such cases, the use of currency swaps or captions is probably more appropriate. To calculate the notional amount of swap needed, it will probably be necessary for the firm to build a model of its expected cash inflows and outflows over the proposed life of the swap. To incorporate the strategic risk of currency changes, it should also try to model the price elasticity of its sales to changes in exchange rates.

Modeling of the notional amount of a currency swap needed is not a trivial task and it is likely that several heroic assumptions and forecasts will be needed. Thus, it is probably best to use the currency swap as a base hedge and frequently monitor its effectiveness. Forwards and options can then be used to make adjustments throughout the life of the swap as model assumptions change and correlations between currencies change.

Like all derivatives, currency derivatives can be cash settled or physically settled. In a cash-settled currency derivative, the exchange rate difference is paid in units of the domestic currency. Conceptually there is not a difference between physically settling a derivative transaction or having it cash settled. However, for currency swaps that have exchange of physical, there is a significant difference in the amount of counterparty risk and thus it is worthwhile to take a look at the mechanics of a currency swap that involves exchange of notional at the beginning and at the termination of the swap.

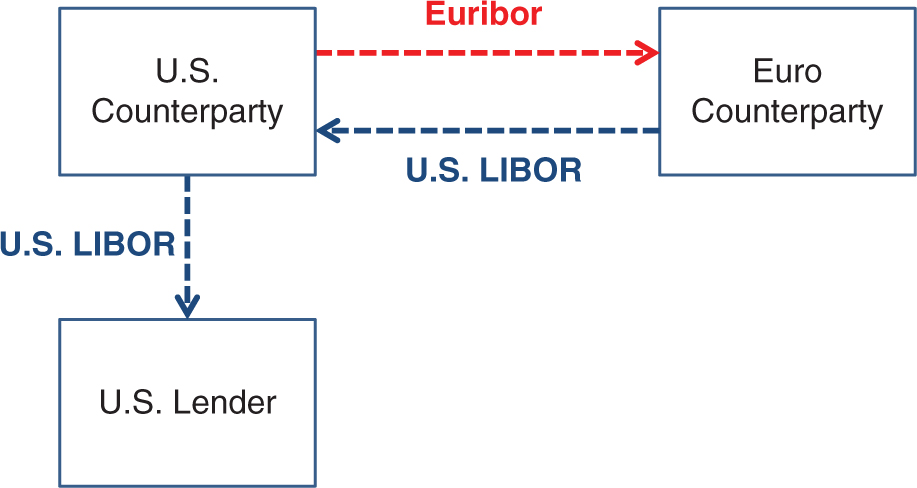

For a currency swap that has exchange of principal, there is basically a three-step process. Consider the example of a 5-year swap of US$50MM for €41.5MM. Assume that the floating legs of the swap are U.S. dollar LIBOR and Euribor, respectively, on a semi-annual basis. The U.S. counterparty will receive Euribor and there will be an initial exchange between the two counterparties of US$50MM for €41.5MM as shown in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 First step of a currency swap with physical exchange of notionals

For the 5-year life of the swap, the swap payments based on the two floating interest rates will be made as shown in Figure 6.2. The U.S. counterparty will make payments based on a notional of €41.5MM and the Euribor rate, while the euro counterparty will make payments on a notional of US$5MM and based on the U.S. dollar LIBOR rate.

Figure 6.2 Interim swap payments

In the final step, the principal amounts will again be exchanged, only this time, with the currency flows going the other way as shown in Figure 6.3.

Figure 6.3 Final exchange of notionals

An issue is that over the 5-year life of the swap, the U.S. dollar and euro exchange rate could have changed quite significantly. This potentially leaves quite a large counterparty exposure for each of the counterparties. In an interest rate swap, or a commodity swap, the counterparty exposure actually decreases as the swap nears maturity. For a currency swap with exchange of principals, the counterparty exposure actually increases. For this reason, currency swaps can also be completed, but without the exchange of principals at inception and at maturity of the swap.

Case Study

Caterpillar

From mines in Australia to construction sites in Alabama, few sights are more ubiquitous than the heavy machinery of Caterpillar, painted yellow with the contrasting black “CAT” lettered prominently. The world’s leading manufacturer of construction and mining equipment, in 2016 Caterpillar generated total revenue of $38.5 billion primarily from three segments: construction industries, resource industries, and energy & transportation.2 Approximately three-fifths of its revenue comes from countries other than the United States, with Caterpillar dealers serving 190 countries.3 Operating a global corporation provides many benefits in terms of diversification of revenue, but also presents challenges in managing exposure to fluctuations in foreign exchange. When operating outside of the United States, much of Caterpillar’s revenue will be denominated in the local currency—pesos in Mexico, euros in Spain, or dong in Vietnam—but Caterpillar’s earnings are reported, dividends are paid, and interest on much of its debt is paid, in U.S. dollars. In addition, its operating expenses will be in a wide array of currencies. As global exchange rates fluctuate, Caterpillar’s earnings, in U.S. dollars, will fluctuate as well.

How does Caterpillar manage its foreign exchange risk? In its 10-K filing, Caterpillar states

Machinery, Energy & Transportation operations use foreign currency forward and option contracts to manage unmatched foreign currency cash inflow and outflow. Our objective is to minimize the risk of exchange rate movements that would reduce the U.S. dollar value of our foreign currency cash flow. Our policy allows for managing anticipated foreign currency cash flow for up to five years.

This short statement contains a great deal of information about its foreign exchange hedging including what is being hedged, the objective of its hedging program, what financial products are used, and the time frame over which the risk is managed. By managing its currency risk in this manner, Caterpillar is sending a message that when an investor purchases shares in the company, they are investing in the operational core competencies of the company—e.g., manufacturing and selling heavy machinery—without being completely exposed to fluctuating foreign exchange rates. Another dimension of foreign exchange risk that Caterpillar must be mindful of is that as an exporter, a strengthening U.S. dollar makes its products more expensive to foreign buyers (in their local currency).

Although Caterpillar is an extreme example operating in 190 countries, in today’s increasingly global marketplace, almost all medium and large enterprises (and even many smaller ones) will have some exposure to exchange rate variability. After identifying its currency exposures, a firm must decide whether or not to hedge this risk, and what tools to use if it does choose to hedge. Caterpillar provides an excellent example of a large company with significant foreign exchange exposures that has implemented a broad hedging strategy.

Currency swaps are also frequently used for financing purposes. A company may have a funding need for one currency, but have a funding need in a second currency. Assume that our U.S. counterparty in the previous example had a need for €41.5MM, but was having difficulty securing euro financing at attractive rates. Also assume that the company was able to secure financing in U.S. dollar easily and at a U.S. LIBOR rate that was acceptable. The U.S. counterparty could thus secure financing in U.S. dollars, and enter into a physically settled currency swap. The three steps of the currency swap would then be as follows.

Figure 6.4 shows that the U.S. counterparty is borrowing US$50MM and immediately swapping it for €41.5MM. The net cash flow for the U.S. counterparty is a cash inflow of €41.5MM.

Figure 6.4 Currency swap combined with domestic borrowing

Figure 6.5 shows the interim cash flows over the 5-year life of the swap. It is also assumed that the terms of the loan are also 5 years on a semi-annual basis and that the swap dates are set to be equivalent to the interest payment dates on the loan. At each loan interest payment, the amount of the U.S. dollar payment is offset by the cash inflow of the U.S. dollar payment from the swap. In turn, the net payment by the U.S. counterparty at each payment date is simply the euro payment on the swap.

Figure 6.5 Interim swap payments

Figure 6.6 shows the maturity payments. The maturity payment of US$50MM on the loan is offset by the US$50MM received from the swap payment. The net payment by the U.S. counterparty will be the €41.5MM payment on the swap.

Figure 6.6 Currency swap maturity payments

Thus at inception, the U.S. counterparty receives a net payment of €41.5MM. Interim payments over the 5-year life of the transactions are that the U.S. counterparty makes a semi-annual payment of Euribor on €41.5MM. At maturity, the U.S. counterparty makes a net payment of €41.5MM on the swap. Notice that the net payments are exactly as if the U.S. counterparty had executed a €41.5MM loan. In essence, the U.S. counterparty has synthetically created a euro-based loan through funding at advantageous rates (and presumably with more ease) in the U.S. loan market and entering into a currency swap. If the U.S. counterparty has euro-based sales receipts, they have effectively hedged these receipts through the use of the synthetic euro loan. If the euro depreciates, then so will the net payments that the U.S. counterparty needs to make on the swap. Note, however, that this analysis does not account for any sales elasticity due to exchange rate fluctuations. If the euro depreciates, it will make the U.S. company’s products more expensive in euros, which in turn may negatively affect sales.

Before leaving the subject of currency swaps, it is important to note that the previous example in which a U.S. company borrows in U.S. dollars and then swaps for euros can also be used to gain a funding advantage. Large multinational companies will canvas global markets to find the currencies in which they can most attractively get funding. They then use the above strategy of currency swaps to swap into the currency in which they actually want to use the currency. In doing so, they get attractive funding, and they get currency risk management. This is a very popular tactic for companies that are comfortable with using and executing currency swaps.

Earlier in this section, some of the specific difficulties of managing currency risk were mentioned; namely that a typical company will have a large number of foreign currency transactions, and additionally that it is likely to have exposure to several different currencies with differing correlations. Both issues make the calculation of the exposure and of the amount of foreign exposure to hedge quite challenging. To overcome these difficulties, there are a couple of exotic derivatives that are frequently employed in hedging currency risk.

Average Rate Options, also called Asian Options, calculate the payment based on an average of the rate over a period, rather than the exchange rate on a given date. Average Rate Options have several advantages. Firstly, they are not tied to a specific date and thus the concern about having a mismatch between the date in which a foreign currency transaction is done and the date on which the hedge is calculated is reduced. If a company has a series of cash transactions occurring over the month, it can enter into an Average Rate Option and achieve a hedge payout based on the average exchange rate over the month. While this is not a perfect hedge, it closely approximates the average rate at which the company will be transacting in the foreign currency. A second advantage of Average Rate Options is that they are generally much less expensive due to the calculus of pricing these options.

A second type of exotic option that is useful for hedging currency risk is a Basket Option. In a Basket Option, the payout is based on how the currency performs against a basket of foreign currencies. For instance, you could buy a hedge on the U.S. dollar versus a basket consisting of the euro, the British pound, and the Canadian dollar. In essence, the payout of the Basket Option is based on the average performance of the U.S. dollar versus these three currencies. Over the life of the option, it is likely that some of these currencies would have appreciated against the U.S. dollar and some would have depreciated. Thus, the payout of the Basket Option will be muted based on the offsetting effects of the appreciation of some and depreciation of the other currencies, but this muted payout will match the exposure of the company doing the hedging. Like with the Average Rate Option, the pricing of the Basket Option will be less expensive than entering into a series of equivalent conventional options on the three currencies. The averaging effect again reduces the implied volatility, and also reduces the expected total payout, but also matches more closely the actual exposure that the company is facing.

As with all exotic options, the pricing is nonstandard, more difficult, and involves more assumptions. This means that different dealers are more likely to have different prices and thus it pays to do some due diligence and ensure that one entering into these more advanced transactions is getting a fair transaction price.

Concluding Thoughts

While all financial risks can affect a company both in terms of their transactions, as well as in terms of their strategic competitiveness, currency risk has the greatest potential to affect the competitive position of a company relative to its foreign-based peers. Fortunately, the currency market is very large and very liquid. Thus, there are a plethora of financial tools and strategies that firms can use to not only manage this risk, but also use it to gain a competitive advantage.

Exchanges rates, and more accurately, changes in exchange rates are directly tied to changes in the relative interest rates between two countries. This effect, known as Interest Rate Parity, gives rise to unique financing opportunities, whereby a firm can use currency derivatives to not only manage currency risk, but also potentially gain a funding cost advantage.

________________

1In reality, the relationship for arbitrage is not perfect as we have ignored bid-ask spreads in trading the currency as well as bid-ask spreads in the borrowing/investing rates. Also, currency and investment or borrowing controls may affect the arbitrage relationship.

2https://www.caterpillar.com/en/company.html

3Caterpillar. “Caterpillar Inc.: Overview.” http://s7d2.scene7.com/is/content/Caterpillar/CM20171201-48288-53810