24. Handling Errors

In This Chapter

What Happens When an Error Occurs?

Basic Error Handling with the On Error GoTo Syntax

Errors While Developing Versus Errors Months Later

Errors Caused by Different Versions

Errors are bound to happen. Even when you test and retest your code, after a report is put into daily production and used for hundreds of days, something unexpected will eventually happen. Your goal should be to try to head off obscure errors as you code. For this reason, you should always be thinking of what unexpected things could happen someday that could make your code not work.

What Happens When an Error Occurs?

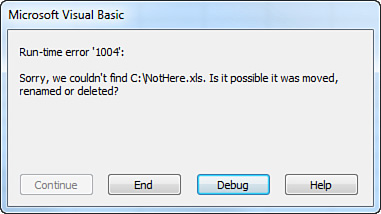

When VBA encounters an error and you have no error-checking code in place, the program stops and presents you or your client with the 1004 runtime error message, as shown in Figure 24.1.

When presented with the choice to end or debug, you should click Debug. (If Debug is grayed out, then someone has protected the VBA code, and you will have to call the developer.) The VB Editor highlights in yellow the line that caused the error. When you hover the cursor over any variable, you see the current value of the variable, which provides a lot of information about what could have caused the error (see Figure 24.2).

Figure 24.2 After clicking Debug, the macro is in break mode. Hover the cursor over a variable; after a few seconds, the current value of the variable is shown.

Especially in older versions, Excel has been notorious for returning error messages that are not very meaningful. For example, dozens of situations can cause a 1004 error. Seeing the offending line highlighted in yellow and examining the current value of any variables helps you discover the real cause of an error. However, many error messages in Excel 2016—including the VBA error messages—are more meaningful than the equivalent message in Excel 2010.

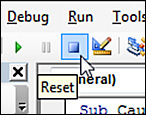

After examining the line in error, click the Reset button to stop execution of the macro. The Reset button is the square button under the Run item in the main menu, as shown in Figure 24.3.

Figure 24.3 The Reset button looks like the Stop button in the set of three buttons that resembles a DVD control panel.

If you fail to click Reset to end the macro and then attempt to run another macro, you are presented with the annoying error message shown in Figure 24.4. The message is annoying because you start in Excel, but when this message window is displayed, the screen automatically switches to display the VB Editor. You can see the Reset button in the background, but you cannot click it due to the message box being displayed. However, immediately after you click OK to close the message box, you are returned to the Excel user interface instead of being left in the VB Editor. Because this error message occurs quite often, it would be more convenient if you could be returned to the VB Editor after clicking OK.

Figure 24.4 This message appears if you forget to click Reset to end a debug session and then attempt to run another macro.

A Misleading Debug Error in Userform Code

After you click Debug, the line highlighted as the error can be misleading in some situation. For example, suppose you call a macro that displays a userform. Somewhere in the userform code, an error occurs. When you click Debug, instead of showing the problem inside the userform code, Excel highlights the line in the original macro that displayed the userform. Follow these steps to find the real error:

1. After the error message box shown in Figure 24.5 is displayed, click the Debug button.

You see that the error allegedly occurred on a line that shows a userform, as shown in Figure 24.6. Because you have read this chapter, you know that this is not the line in error.

2. Press F8 to execute the Show method. Instead of getting an error, you are taken into the Userform_Initialize procedure.

3. Keep pressing F8 until you get the error message again. Stay alert because as soon as you encounter the error, the error message box is displayed. Click Debug, and you are returned to the userform.Show line. It is particularly difficult to follow the code when the error occurs on the other side of a long loop, as shown in Figure 24.7.

Figure 24.7 With 25 items to add to the list box, you must press F8 53 times to get through this three-line loop.

Imagine trying to step through the code in Figure 24.7. You carefully press F8 5 times with no problems through the first pass of the loop. Because the problem could be in future iterations through the loop, you continue to press F8. If there are 25 items to add to the list box, 48 more presses of F8 are required to get through the loop safely. Each time before pressing F8, you should mentally note that you are about to run some specific line.

At the point shown in Figure 24.7, the next press of the F8 key displays the error and returns you to the frmChoose.Show line back in Module1. This is an annoying situation.

At that point, you need to start pressing F8 again. If you can recall the general area where the debug error occurred, click the mouse cursor in a line right before that section and use Ctrl+F8 to run the macro up to the cursor. Alternatively, right-click that line and choose Run to Cursor.

Sometimes an error will occur within a loop. Add Debug.Print i inside the loop and use the Immediate pane (which you open by pressing Ctrl+G) to locate which time through the loop caused the problem.

Basic Error Handling with the On Error GoTo Syntax

The basic error-handling option is to tell VBA that in case of an error, you want to have code branch to a specific area of the macro. In this area, you might have special code that alerts users of the problem and enables them to react.

A typical scenario is to add the error-handling routine at the end of the macro. To set up an error handler, follow these steps:

1. After the last code line of the macro, insert the code line Exit Sub. This makes sure that the execution of the macro does not continue into the error handler.

2. After the Exit Sub line, add a label. A label is a name followed by a colon. For example, you might create a label called MyErrorHandler:.

3. Write the code to handle the error. If you want to return control of the macro to the line after the one that caused the error, use the statement Resume Next.

In your macro, just before the line that might likely cause the error, add a line reading On Error GoTo MyErrorHandler. Note that in this line, you do not include the colon after the label name.

Immediately after the line of code that you suspect will cause the error, add code to turn off the special error handler. Because this is not intuitive, it tends to confuse people. The code to cancel any special error handling is On Error GoTo 0. There is no label named 0. Instead, this line is a fictitious line that instructs Excel to go back to the normal state of displaying the debug error message when an error is encountered. This is why it is important to cancel the error handling.

The following code includes a special error handler to handle the necessary action if the file has been moved or is missing:

Sub HandleAnError()

Dim MyFile as Variant

' Set up a special error handler

On Error GoTo FileNotThere

Workbooks.Open Filename:="C:NotHere.xls"

' If we get here, cancel the special error handler

On Error GoTo 0

MsgBox "The program is complete"

' The macro is done. Use Exit sub, otherwise the macro

' execution WILL continue into the error handler

Exit Sub

' Set up a name for the Error handler

FileNotThere:

MyPrompt = "There was an error opening the file. " & _

"It is possible the file has been moved. " & _

"Click OK to browse for the file, or click " & _

"Cancel to end the program"

Ans = MsgBox(Prompt:=MyPrompt, Buttons:=vbOKCancel)

If Ans = vbCancel Then Exit Sub

' The client clicked OK. Let him browse for the file

MyFile = Application.GetOpenFilename

If MyFile = False Then Exit Sub

' If the 2nd file is corrupt? Do not recursively throw

' back into this error handler. Just stop the program.

On Error GoTo 0

Workbooks.Open MyFile

' If we get here, then return back to the original

' macro, to the line after the the error.

Resume Next

End Sub

You definitely do not want this error handler invoked for another error later in the macro, such as a divide-by-zero error.

Note

It is possible to have more than one error handler at the end of a macro. Make sure that each error handler ends with either Resume Next or Exit Sub so that macro execution does not accidentally move into the next error handler.

Generic Error Handlers

Some developers like to direct any error to a generic error handler to make use of the Err object. This object has properties for error number and description. You can offer this information to the client and prevent her from getting a debug message. Here is the code to do this:

On Error GoTo HandleAny

Sheets(9).Select

Exit Sub

HandleAny:

Msg = "We encountered " & Err.Number & " - " & Err.Description

MsgBox Msg

Exit Sub

Handling Errors by Choosing to Ignore Them

Some errors can simply be ignored. For example, suppose you are going to use VBA to write out an index.html file. Your code erases any existing index.html file from a folder before writing out the next file.

The Kill (FileName) statement returns an error if FileName does not exist. This probably is not something you need to worry about. After all, you are trying to delete the file, so you probably do not care whether someone already deleted it before running the macro. In this case, tell Excel to just skip over the offending line and resume macro execution with the next line. The code to do this is On Error Resume Next:

Sub WriteHTML()

MyFile = "C:Index.html"

On Error Resume Next

Kill MyFile

On Error Goto 0

Open MyFile for Output as #1

' etc...

End Sub

Note

Be careful with On Error Resume Next. You can use it selectively in situations in which you know that the error can be ignored. You should immediately return error checking to normal after the line that might cause an error with On Error GoTo 0.

If you attempt to have On Error Resume Next skip an error that cannot be skipped, the macro immediately steps out of the current macro. If you have a situation in which MacroA calls MacroB, and MacroB encounters a nonskippable error, the program jumps out of MacroB and continues with the next line in MacroA. This is rarely a good thing.

VBA code to handle printer settings runs much faster if you turn off PrintCommunication at the beginning of the preceding code and turn it back on at the end of the code. This trick was new in Excel 2010. Before that, Excel would pause for almost a half-second during each line of print setting code. Now the whole block of code runs in less than a second.

Suppressing Excel Warnings

Some messages appear even if you have set Excel to ignore errors. For example, try to delete a worksheet using code, and you still get the message “You can’t undo deleting sheets, and you might be removing some data. If you don’t need it, click Delete.” This is annoying. You do not want your clients to have to answer this warning; it gives them a chance to choose not to delete the sheet your macro wants to delete. In fact, this is not an error but an alert. To suppress all alerts and force Excel to take the default action, use Application.DisplayAlerts = False, like this:

Sub DeleteSheet()

Application.DisplayAlerts = False

Worksheets("Sheet2").Delete

Application.DisplayAlerts = True

End Sub

Encountering Errors on Purpose

Because programmers hate errors, this concept might seem counterintuitive, but errors are not always bad. Sometimes it is faster to simply encounter an error.

Suppose, for example, that you want to find out whether the active workbook contains a worksheet named Data. To find this out without causing an error, you could use the following eight lines of code:

DataFound = False

For Each ws in ActiveWorkbook.Worksheets

If ws.Name = "Data" then

DataFound = True

Exit For

End if

Next ws

If not DataFound then Sheets.Add.Name = "Data"

If your workbook has 128 worksheets, the program loops through 128 times before deciding that the data worksheet is missing.

An alternative is to try to reference the Data worksheet. If you have error checking set to Resume Next, the code runs, and the Err object is assigned a number other than zero:

On Error Resume Next

X = Worksheets("Data").Name

If Err.Number <> 0 then Sheets.Add.Name = "Data"

On Error GoTo 0

This code runs much faster. Errors usually make programmers cringe. However, in this case and in many other cases, the errors are perfectly acceptable.

Training Your Clients

Suppose you are developing code for a client across the globe or for the administrative assistant so that he can run the code while you are on vacation. In both cases, you might find yourself trying to debug code remotely while you are on the telephone with the client.

For this reason, it is important to train clients about the difference between an error and a simple MsgBox. Even though a MsgBox is a planned message, it still appears out of the blue with a beep. Teach your users that error messages are bad, but not everything that pops up is an error message. For example, I had a client who kept reporting to her boss that she was getting an error from my program. In reality, she was getting an informational MsgBox message. Both debug errors and MsgBox messages beep at the user, and this user didn’t know that there’s a difference between them.

Train clients to call you while any debug messages they get are still onscreen. This way you can get the error number and description. You also can ask the client to click Debug and tell you the module name, the procedure name, and which line is in yellow. Armed with this information, you can usually figure out what is going on. Without this information, it is unlikely that you will be able to resolve the problem. Getting a call from a client saying that there was a 1004 error is of little help because 1004 is a catchall error that can mean any number of things.

Errors While Developing Versus Errors Months Later

When you have just written code that you are running for the first time, you expect errors. In fact, you might decide to step through code line by line to watch the progress of the code the first time through.

It is another thing to have a program that has been running daily in production suddenly stop working because of an error. That can be perplexing. The code has been working for months, so why did it suddenly stop working today? It is easy to blame the client. However, when you get right down to it, it is really the fault of developers for not considering the possibilities.

The following sections describe a couple of common problems that can strike an application months later.

Runtime Error 9: Subscript Out of Range

You set up an application for a client and you provided a Menu worksheet where some settings are stored. Then one day this client reports getting the error message shown in Figure 24.8.

Figure 24.8 Runtime error 9 often occurs when you expect a worksheet to be there, but it has been deleted or renamed by the client.

Your code expected a worksheet named Menu. For some reason, the client either accidentally deleted the worksheet or renamed it. When the client then tried to select the sheet, she received an error:

Sub GetSettings()

ThisWorkbook.Worksheets("Menu").Select

x = Range("A1").Value

End Sub

This is a classic situation where you cannot believe that the client would do something so crazy. After you have been burned by this one a few times, you might go to lengths like implementing this code to prevent an unhandled debug error:

Sub GetSettings()

On Error Resume Next

x = ThisWorkbook.Worksheets("Menu").Name

If Not Err.Number = 0 Then

MsgBox "Expected to find a Menu worksheet, but it is missing"

Exit Sub

End If

On Error GoTo 0

ThisWorkbook.Worksheets("Menu").Select

x = Range("A1").Value

End Sub

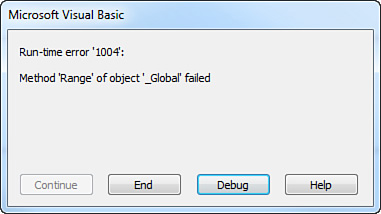

Runtime Error 1004: Method Range of Object Global Failed

You have code that imports a text file each day. You expect the text file to end with a Total row. After importing the text, you want to convert all the detail rows to italic.

The following code works fine for months:

Sub SetReportInItalics()

TotalRow = Cells(Rows.Count,1).End(xlUp).Row

FinalRow = TotalRow - 1

Range("A1:A" & FinalRow).Font.Italic = True

End Sub

Then one day, the client calls with the error message shown in Figure 24.9.

Upon examining the code, you discover that something bizarre went wrong when the text file was transferred via FTP to the client that day. The text file ended up as an empty file. Because the worksheet was empty, TotalRow was determined to be row 1. If you assume that the last detail row was TotalRow - 1, the code is set up to attempt to format row 0, which clearly does not exist.

After an episode like this, you find yourself writing code that preemptively looks for this situation:

Sub SetReportInItalics()

TotalRow = Cells(Rows.Count,1).End(xlUp).Row

FinalRow = TotalRow - 1

If FinalRow > 0 Then

Range("A1:A" & FinalRow).Font.Italic = True

Else

MsgBox "It appears the file is empty today. Check the FTP process"

End If

End Sub

The Ills of Protecting Code

It is possible to lock a VBA project so that it cannot be viewed. However, doing so is not recommended. When code is protected and an error is encountered, your user is presented with an error message but no opportunity to debug. The Debug button is there, but it is grayed out and useless in helping you discover the problem.

Further, the Excel VBA protection scheme is horribly easy to break. Programmers in Estonia offer $40 software that lets you unlock any project. Therefore, you need to understand that office VBA code is not secure—and then get over it.

If you absolutely need to truly protect your code, invest $100 for a license to Unviewable+ VBA Project from Esoteric Software. This crowd-funded software allows you to create a compiled version of a workbook where no one will be able to view the VBA. For more details, visit http://mrx.cl/hidevba.

More Problems with Passwords

Office 2013 introduced a new SHA-2 class SHA512 algorithm to calculate encryption keys. This algorithm causes significant slowdowns in macros that protect or unprotect sheets.

The password scheme for any version of Excel from 2002 forward is incompatible with Excel 97. If you protected code in Excel 2002, you cannot unlock the project in Excel 97. As your application is given to more employees in a company, you will invariably find an employee using Excel 97. Of course, that user will come up with a runtime error. However, if you locked the project in Excel 2002 or newer, you are not able to unlock the project in Excel 97, which means you cannot debug the program in Excel 97.

Bottom line: Locking code causes more trouble than it is worth.

If you are using a combination of Excel 2003 through Excel 2016, the passwords transfer easily back and forth between versions. This holds true even if the file is saved as an .xlsm file and opened in Excel 2003 using the file converter. You can change code in Excel 2003, save the file, and successfully round-trip back to Excel 2016.

Errors Caused by Different Versions

Microsoft improves VBA in every version of Excel. Pivot table creation was improved dramatically between Excel 97 and Excel 2000. Sparklines and slicers were new in Excel 2010. The Data Model was introduced in Excel 2013. Power Query was built in to the object model in Excel 2016.

The TrailingMinusNumbers parameter was new in Excel 2002. This means that if you write code in Excel 2016 and then send the code to a client with Excel 2000, that user gets a compile error as soon as she tries to run any code that’s in the same module as the offending code. For this reason, you need to consider this application in two modules.

Module1 has macros ProcA, ProcB, and ProcC. Module2 has macros ProcD and ProcE. It happens that ProcE has an ImportText method with the TrailingMinusNumbers parameter.

The client can run ProcA and ProcB on the Excel 2000 machine without problem. As soon as she tries to run ProcD, she gets a compile error reported in ProcD because Excel tries to compile all of Module2 when she tries to run code in that module. This can be incredibly misleading: An error being reported when the client runs ProcD is actually caused by an error in ProcE.

One solution is to have access to every supported version of Excel and test the code in all versions.

Macintosh users will believe that their version of Excel is the same as Excel for Windows. Microsoft promised compatibility of files, but that promise ends in the Excel user interface. VBA code is not compatible between Windows and the Mac. Excel VBA on the Mac in Excel 2016 is close to Excel 2016 VBA but annoyingly different. Further, anything you do with the Windows API is not going to work on a Mac.

Next Steps

In this chapter you’ve learned how to make your code more bulletproof for your clients. In Chapter 25, “Customizing the Ribbon to Run Macros,” you find out how to customize the ribbon to allow your clients to enjoy a professional user interface.