Chapter 1

INTRODUCING THE PAST, PRESENT, AND

FUTURE OF THE WEB

Believe it or not, when we were kids, the standard way to send written text to someone was by mail. Not e-mail, mind you, but the physical kind requiring a stamp on the envelope. Admittedly, this makes us feel incredibly old. Right up until middle school, we would submit handwritten assignments, just like everybody else in our classes. It was the standard.

The Internet is a reasonably new invention, and the World Wide Web is even newer. Yet both have had as profound an impact on civilization as the printing press, the steam engine, or the lightbulb. When we were growing up, we had an impossible time finding good video games for our PCs. Computers were all about business then. We could find six different word processors, but we couldn't find the latest release from Sierra Online (which is owned by Electronic Arts now). These days, if you are looking for a video game, where do you go? The average person will head over to Amazon and preorder their copy of the latest title for next-day shipping. E-commerce has become so ubiquitous that, for certain products, it is preferred over a trip to the local store.

The World Wide Web has made nearly everything near-instantly available to nearly everyone with an Internet connection. Even mega-stores, like Wal-Mart, cannot keep pace with the selection available to consumers online. It used to be incredibly hard to find niche products, such as curling stones, but these days, they're only a mouse click away (http://www.kaysofscotland.co.uk/). In remote communities where there is no Wal-Mart, the Internet has become an essential tool for 21st-century living.

The standard way of doing things

Because of its highly technical childhood, the World Wide Web has a lot of "hacker baggage." When we say that, we don't mean that it's a dangerous place where people roam the wires trying to steal your credit card information (although there is some of that too). We're using the term hacker in the classic sense of someone who likes technology and tries to find their own way of solving problems. The Web started off very much from a position of trying to solve a problem, in this case, distributing information. It evolved and gained features out of necessity—people needed to be able to add images and tables to their documents. In the early days of mainstream adoption, when businesses started to move online, there wasn't always a perfect way of doing things, so people came up with their own solutions.

A classic example of this is using a table on a web page to lay it out. At one point, we were guilty of this; but at that point we had no choice. Using a table was the only way you could get two columns of text to display on a page. Today, there are far better options, and that's what this book is about. Web standards have evolved; this isn't 1995 anymore.

Every journey starts with a single step: the Web past

It is hard to find a book about Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) and the Web these days without having it start off with a history section. We used to wonder why that was the case. To understand why the web standards approach to building websites is the best way to go, you have to know about the progression of the World Wide Web as it has evolved to become what it is today. The World Wide Web has very technical roots, and the trouble (or charm) with most techies is that they like to customize—change things until those things are perfect in their minds. They cannot follow what everyone else is doing; they need to add their own flavor to it.

The Web started its life as a research project at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Geneva, Switzerland. At the time, a researcher there by the name of Tim Berners-Lee was looking for a way to quickly and easily share research findings with his peers and organize information in such a way that it would be easy to archive and retrieve. Although the process was started in the early 1980s, it wasn't until 1990 that Berners-Lee produced the first web server and web browser (which was called WorldWideWeb, the origin of the name).

In 1992, the Web began to hit the mainstream when the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) in the United States released Mosaic, which was capable of displaying text and graphics simultaneously. Mosaic gave nonscientists easy access over the Internet to documents created using HTML, what we now call web pages. Encouraged by this early success, one of Mosaic's creators, Marc Andreesen, left the NCSA and started Mosaic Communications Corporation. This later became Netscape Communications Corporation, creators of Netscape Navigator, which was the first commercial browser and the web standard-bearer through most of the 1990s.

A company called Spyglass licensed NCSA's source code and eventually released Spyglass Mosaic (though on a newly developed code base). This became the basis for Microsoft Internet Explorer and set the stage for the battle for browser supremacy between Netscape and Microsoft.

Just prior to the start of the "browser wars" of the 1990s, Berners-Lee recognized that without some sort of governance, the World Wide Web would experience great challenges as competing web browsers introduced new features. One of the ways to get someone to pick your product over your competition was to offer a bunch of really cool features that the other guy didn't offer. He foresaw compatibility problems emerging as competing companies introduced their own tags in order to add features to the World Wide Web. HTML was the glue binding the Web together, and some central body would need to oversee its evolution in order to maintain a high level of interoperability.

Microsoft gave away Internet Explorer as part of Microsoft Office, bundled it with Windows, and made it available as a free download for all its various operating systems, as well as for Macs. Microsoft was a late starter in the browser market, and by the time it entered the game in 1995, Netscape had an estimated 80 percent market share. The tides rapidly turned, however, and by the time Netscape was acquired by America Online in 1998, Microsoft had approximately half of the web browser market. By 2002, Internet Explorer reached its peak with an estimated 96 percent of web surfers using Internet Explorer. In fact, Microsoft so thoroughly thrashed Netscape in the browser wars that they ended up in a contracted lawsuit that eventually led to a finding of Microsoft's abuse of monopoly power in the marketplace. Figure 1-1 shows a timeline of major browser releases, starting in the early 1990s.

Figure 1-1. Timeline of major browser releases

The browser wars were an incredibly difficult time for web developers as manufacturers raced to do their own thing. Versions 3 and 4 of the major browsers often had developers coding two entirely separate versions of their websites in order to ensure compatibility with both Internet Explorer and Netscape. Although web standards existed, most browsers only really supported the basics and relied on competing (and incompatible) technology to do anything advanced, which is what web developers wanted to do.

Netscape, although owned by a fairly major company, started to stagnate. Netscape open sourced its code base, and the Mozilla project was born. The Mozilla community took off with the code and started to really implement standards support in a new way through a complete rewrite of the rendering engine. Although Mozilla was, early on, based on Netscape Navigator, the tables rapidly turned, and subsequent releases of Netscape became based on Mozilla.

The Mozilla project has forked into a number of new browsers, most notably Firefox, which has sparked a new browser war with Microsoft. Yet this time, the battle has had a positive effect. Microsoft had all but stopped working on Internet Explorer once it released version 6. When Firefox hit the scene with near-perfect support for web standards, it became an immediate hit and gained a great deal of popularity with both the web cognoscenti and the general public. It seems as though Microsoft had no choice but to improve its web browser, and the result is Internet Explorer 7.

A number of other players emerged in the web browser marketplace, offering competition to the major players. Notably, Opera has always touted excellent support for web standards as one of its major selling features. It has caught on to some degree (2 percent as of January 2008) and is also focusing in a large part on mobile devices.

Safari by Apple Computer hit the scene in 2003 and quickly became one of the most popular choices for Mac users because it integrates well with the operating system and is generally faster than competing browsers on the Mac. Apple introduced a Windows version in 2007, but that product has yet to leave beta. One of the most unique qualities of Safari is that even with its minor updates (so-called point releases), Safari has improved its support of web standards, something that is often relegated to major releases among other browser manufacturers.

Then there were standards: the Web now

Could you imagine if each TV channel was broadcast in either PAL or NTSC in each country, requiring viewers to use a different TV set depending on what they wanted to watch? Similarly, imagine writing a research paper, running a search on Google, and then having to open each of the results returned in a different web browser. The first link is Internet Explorer, the second and third are Netscape... OK, now back to Internet Explorer... Yet, this is pretty much how things worked in the late 1990s. One of the most common sights on the Web were these wonderful (heavy sarcasm here) graphic badges telling visitors that this website is "Optimized for Internet Explorer" or "Best Viewed with Netscape Navigator" (see Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2. Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigation "get it now" buttons

When we talk about web standards, we're generally referring to the big three players on the Web: HTML (or XHTML), Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), and JavaScript. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) maintains many other standards, such as Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) for vector graphic display, Portable Network Graphics (PNG) as a way to compress bitmap graphics, and Extensible Markup Language (XML), which is another markup language, similar in a lot of ways to HTML.

While HTML/XHTML is all about structuring your document, CSS handles formatting and displaying your various page elements. Because they're two separate pieces of technology, you can separate them (by separating content from display). The early versions of HTML (prior to the release of CSS) were intended to be everything to everyone. The ability to specify colors and fonts was built right in by specifying the attributes of various tags. As sites began to grow in size, however, the limitations of going this route quickly became apparent.

Imagine that you have put together a website to promote this book. Throughout the site, which covers all the chapters in detail, there are quotes from the book. To really make these quotes jump off the screen, you are going to put them in red and make them a size bigger. In the good old days, your code would look something like this:

<font size="+1" color="red">In the good old days, ![]()

your code would look something like this:</font>

With a little XHTML and CSS, the code could look like this (note we said "could" because there are multiple ways of doing things—this is a good, structurally relevant example):

<blockquote>In the good old days, ![]()

your code would look something like this:</blockquote>

And then in a separate CSS file (or at the top of your HTML document—but again, that's just another option) that you would import/link to on pages of your website, there would be something like this:

blockquote { font-size: 1.5em; color: red; }

So what? They both do the same thing. Web browsers will display the quotes in red and make them nice and big. One of the immediate advantages, however, is in making updates. As we mentioned previously, you are liberally quoting the book throughout the entire website, chapter by chapter. By the end of the project, you discover that you have used more than 300 quotes! The only problem is that we, as the authors (and your client), absolutely hate red text. It makes us so angry. So, we're going to ask you to change it everywhere.

What would you rather do: update one line in the CSS file or open every page on the site and change the color attribute to blue? (Blue is much more calming.) Three hundred quotes—you're billing by the hour—so that's not so bad. It's maybe an extra half day of work. Now extrapolate this example to something like the New York Times where there are quite likely millions of quotes throughout the entire website. Are you still keen to go change every font tag?

You're thinking to yourself, "My software can do search and replace." This is true. We were once asked to update a department website at an organization where we worked. The website had about 16,000 pages, and by the end of a week, our search and replace still hadn't finished. We're not that patient. Are you?

Additionally, CSS has evolved and is still evolving, allowing designers and developers to do more and more in terms of the layout and appearance of their pages. Using CSS you can position any element anywhere you like on a page. Although you could probably accomplish the same thing with a table-based layout, it would probably take you a considerable chunk of code including setting absolute heights and widths of table cells. One thing you can't do, however, is overlap a pair of table cells, which is something that's extremely easy to do using CSS.

The upcoming release of CSS (version 3) has even more formatting options baked in. You will be able to specify multiple background images for an element, set the transparency of colors, allow certain elements to be resized on the fly, and add drop shadows to text and other elements on the fly. Check out the W3C website or, for a slightly more human-readable form, http://www.css3.info for more information.

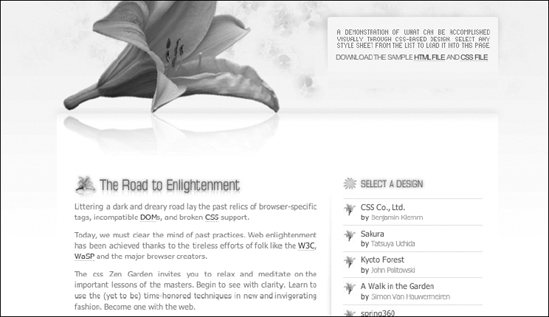

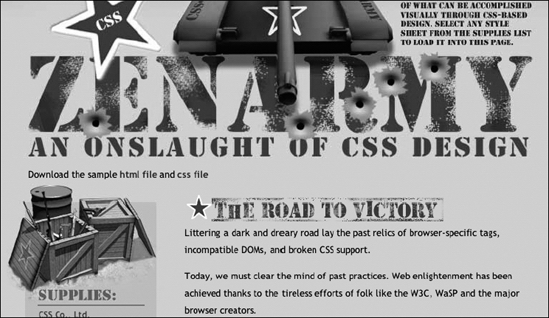

The provided example is a pretty simple representation of what you can do using XHTML and CSS. If you head over to the CSS Zen Garden (http://csszengarden.com/) and click through some of the examples there, you can gain an appreciation for the level of control you can have by tweaking the CSS for a website. CSS Zen Garden uses the same markup for every example (the XHTML part stays the same on every page). The only thing that is different on each page is the CSS file that is included, as well as any supporting graphics (see Figure 1-3, Figure 1-4, and Figure 1-5).

Figure 1-3. One example from CSS Zen Garden (http://www.csszengarden.com). Each of these pages uses the same XHTML markup; each page is just styled differently using CSS and images.

Figure 1-4. This is the same page as shown in Figure 1-3 but styled using an alternate style sheet at the CSS Zen Garden.

Figure 1-5. A final example showing just how powerful CSS can be at changing the look of a page

Imagine not having to touch a single page of markup when redesigning a website and still getting a completely different end result. Properly structured, standards-based pages will let you do it. This could be a major advantage for companies building large-scale content management systems: simply change the style sheet, and the CMS has been tailored to a new customer. Some companies are doing this, but others haven't caught on yet.

A crystal ball: the Web future

The Web is a cool place in many ways, not least because you don't need to be a fortune-teller to see into the future. Because standards take time to develop, we already have an idea of what the future holds. For example, HTML is being reviewed right now (the current W3C Recommendation is for HTML 4.01, which was released in December 1999). A working group has been formed to look at developing an HTML 5 Recommendation in order to clean up some of the loose ends from HTML 4. The group started in 2006 and is aiming to have the Recommendation ready by the end of December 2010 (as you can see, it's a rigorous process that does take some time).

The W3C process for standards approval goes through numerous steps and can easily span several years. The final product of this process is a W3C Recommendation. Because the W3C isn't a governing body, all it can do is make a recommendation that software companies can then choose to follow. There are no "laws" of the Web, so if Apple decided to drop HTML support in Safari in favor of its own markup language, Apple could. As you can see from our previous history lesson, this wouldn't have been completely out of the question in the 1990s, but today, it would probably be very self-defeating. The culture of the Web is all about interoperability, and when companies attempt to limit interoperability to gain some sort of competitive advantage, we all lose.

This has led to somewhat mixed results. On one hand, you can go to almost any website and have it work in almost any web browser. There are still some companies that are pulling the old "Please download Internet Explorer" trick, but those companies are few and far between. The fact of the matter is that interoperability, for businesses, means a larger potential customer base. For most Mac users, if they visit a website that is "Internet Explorer–only," they're dead in the water. They could purchase a Windows machine or run some virtualization software in order to run Windows on their Mac, but chances are, if they have the choice (and the Web is all about choices), they just won't bother. They'll go find a competitor that supports Safari or, at the very least, Firefox.

The consultation process for developing new standards and revising old ones is very thorough, and it involves a lot of consultation with the community. Several drafts are developed, a great deal of feedback is collected, and eventually a Recommendation is put forth. We've presented HTML and XHTML almost interchangeably in this first chapter. Although both HTML and XHTML are valid web standards, in this book we'll focus on XHTML, which advances the Web by enforcing that pages be well formed and that pages are marked up in such a way that information about their structure is important.

XHTML is a bit of a hybrid between HTML and XML, which is widely used for data storage. The current version of XHTML in use on the Web today is XHTML 1.01, which is a bit of a stepping-stone in the movement toward complete use of XML in page markup. The reason we say that is because although pages are written in XHTML, they are often still displayed by browsers in a way similar to HTML.

Building on standards for the modern Web

We as people have been building physical spaces for thousands of years. There are a whole host of professions involved in constructing a building: architects, engineers, contractors, plumbers, electricians, carpenters, and so on. Likewise, with the Web, numerous specialists contribute to building a great online space (see Table 1-1). You can build the most beautiful museum in the world, but if the client is asking for a factory, you have not done your job.

Table 1-1. A Comparison Between Traditional Construction Jobs and "Digital Construction" Jobs

| Bricks (Buildings) | Bits (World Wide Web) |

| Architect: Draws up the blueprints; makes sure the only bathroom isn't off the garage. | Information architect: Draws up the site map; makes sure site search isn't available only from the "Contact Us" page. |

| Engineer: Ensures that the building is sound, that the proper materials are being used, and that the wind won't blow it over. | Technical lead: Ensures that the systems in place will handle the traffic and that the technology decisions are sound. |

| General contractor/foreman: Makes sure that everyone shows up to work, that the plans are followed, and that the building gets built. | Project manager: Makes sure that the programmers don't spend all their time playing video games and that the project gets done on time. |

| Interior/exterior designer: Selects the paint colors; what art to hang on the walls; and whether to use carpet, tile, or hardwood. Basically, this person makes sure that things look nice. | Designer: Selects the color palette and fonts; develops the graphics. In other words, the designer makes sure that things look nice. |

| Basement/foundation builders: Pours the concrete for the foundation of the structure. | System administrator/database administrators:Creates the infrastructure that supports the website. |

| Framer/carpenter/drywaller/painter: Builds the structure; turns the architect's vision into reality. | HTML/CSS developer: Structures pages properly; puts the designer's vision into practice. |

| Plumber/electrician: Puts in the pipes and wires to make the house come alive. You can live in a house without plumbing and electricity, but it isn't much fun. | Programmer/developer: Adds interactivity to pages through client-side and server-side scripting. |

That said, a single person or a small group of people frequently fills a number of these positions. In this industry, being a generalist is a common way to go. As you will learn later in this book, using web standards can give you a leg up in this area by providing you with a foundation of best industry practices. Architects follow the local building code to make sure their projects are safe and constructed in a consistent way. People building for the Web should do the same to ensure their sites are accessible, search engine–friendly, and consistent in modern browsers.

What's inside this book?

Our goal is to take this book beyond web standards to cover the entire process of developing a website based on standards. Believe it or not, there is more to putting together a great website than just knowing a little HTML (or XHTML, as the case may be). This introduction will expose you to different techniques and technologies, and we hope it will encourage you to pursue those areas you find most compelling.

The other day we received a copy of a magazine that has been in print for 29 years. This issue announced that it would no longer be printed and would henceforth be available only online. Increasingly, companies are moving their advertising efforts online, and more and more industries, especially those that target younger markets, are concentrating on communicating with their potential markets through websites and online communities.

Technologies come and go or, as in the case of HTML, evolve. Two years from now, we may have to completely rewrite sections of this book. We will certainly need to add to the history section as new browsers and technologies are introduced into the market and as new trends emerge (during the writing, Safari for Windows was released, and Firefox 3 will likely be released before this book makes it to bookstores). It's exciting to be working with ever-changing Internet and web technologies. We could even be witnessing the beginnings of a great web transformation with the advent of mobile computing. There's no telling what we'll find around the next corner.