Deciphering the Human Mysteries of Organizational Life

Elizabeth Florent Treacy

Crisis and Change in the Organizational Context

We are all learning to live within a continual state of global upheaval. We contemplate previously unimaginable near-future possibilities that range from climate catastrophe to civilian space travel. We face challenges of crisis and change that have never been paralleled in all of human history.

Not so long ago, the scope of working life for most people was limited primarily to fields, flocks, or factories. With the tragic exception of war, there was comparatively little interaction between countries on a global scale. The Great Man theory of leadership prevailed: if you could get a capable man—an authoritarian leader—at the head of a village or a company, the rest would fall into place.

Today, the world is in a complex, and most likely permanent, state of “stable instability or instable stability.”1 Many people in organizations would say this is good news. Change, in that context, is often seen as being exactly what is needed. “A new broom sweeps clean!” or “It is easier to change people [fire and hire], than to change people [their way of working].”

But the organizational challenges we face now are radical, hard to foresee, and difficult to mitigate—as any organizational leader will admit if you ask what gives him or her nightmares. Those challenges can be deeply intimidating and disturbing for leaders and followers; indeed, psychological distress and related reactions are augmented when a person or group is under stress.2 It is no longer possible for anyone at the head of a business to remain a detached observer, objectively making decisions. Their most frequent question is: “How can I—a key player in my organization—possibly manage this? What am I supposed to do?” In particular, in situations of crisis and change, people behave in unpredictable ways. One senior executive recalled that he was shocked by pandemic-related interactions with his colleagues. Shaking his head in disbelief, he said, “I saw chaos. I saw how mature, educated people can create chaos.” In fact, what he saw was people seeking to divert the focus of attention to irrelevant or alternative issues, in order to distract themselves from the pressure and intensity of the situation.3 Indeed, paradoxically, the common tendency toward survival behavior when under pressure adds yet another source of complexity in periods of disruption.

In the final analysis, crisis and change are increasingly difficult because for organizations in the 21st century, everything and everyone is interrelated, and every interaction creates unpredictable consequences. No single individual can control the functioning of the whole, but one single individual can be the source of a great deal of trouble on a very large scale.

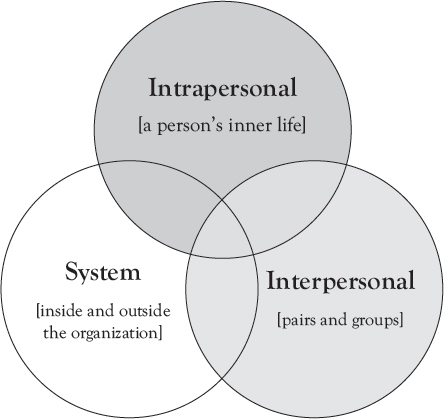

The fundamental challenges of crisis and change in organizations today can be understood and effectively managed by tapping into the broader, more holistic view that a “systems-psychodynamic” approach provides. This view includes three “fields”: the environmental context and organizational system, groups of people in organizations, and what is going on inside each individual.

This holistic perspective allows us to explore the interrelatedness of these three elements. The term systems refers to context and environment: the forces from “outside” as well as the system “reality” that is created by the dynamics of small and large groups.4 Psychodynamic refers to the underlying, out-of-awareness motivational factors and past experiences that influence individuals’ beliefs and behavior patterns. This approach considers what is “within”: the inner world of individuals, including their emotions. (“Psychodynamic” is the term preferred by organizational practitioners, as it reveals how the forces of the unconscious are dynamic, not passive. This term also moves away from the treatment and pathology orientation of psychoanalysis.5) This holistic approach gives us a lens for including both the “visible and measurable” and the “unspoken or unseen” in organizations (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The overlapping spheres of dynamics in organizations

Viewed this way, one sees that an organization is not a machine; it is a collective conversation6 created from shifting, ambiguous relationships between people and their environments. Patterns of action—decisions, indecisions, paranoia, and delusions—emerge from human relationships. When people or organizations are stressed by change or challenged by crisis, these patterns of action—if left hidden and unmentioned—will generate tension and anxiety. Therefore, in the face of crisis and change, a leader cannot direct events in isolation. An employee or stakeholder cannot remain passive and hope for the best, or alternatively, create a cloud of chaos as a distraction technique. Everyone has to be aware of their own power and influence within the system and take responsibility for their own participation.

The systems-psychodynamic approach brings three valuable aspects to the topic of managing adversity and change. First, it is a rigorous and valid method of inquiry and research—a way to analyze what is happening in organizations. This method gives us a view into the unconscious processes of organizational life, “one of the dimensions most resistant to scientific investigation.”7 Second, it enables us to decipher what goes on under the surface in the reciprocal zone of influence where the system, the group, and the individual are susceptible to tension and anxiety.8 Third, systems-psychodynamic methods inform practical applications, ranging from individual reflection and review to group or organization-level interventions such as culture change or crisis recovery. In short, an emphasis on unconscious and emotional processes equips us to “address organizational change and the psychological forces which it unleashes.”9

A Sliver of Light

When asked about his experience with the systems-psychodynamic perspective, one CEO, we’ll call Jack, offered the following story. He recalled the period when he landed his first CEO role. Coming on board, one of his challenges was to carry forward the unifying aspects of the founder’s legacy, while making the organization relevant in the future. After several years of running a “best place to work” survey, Jack noticed with frustration that the results had been the same year after year. No surprises—and no change. The consultants who officiated over the survey ran the numbers and determined that there were four key drivers that the company should focus on in the coming year, in order to improve things. Next year, same results—despite well-intentioned activities and efforts aligned with the identified drivers, no change.

Jack had an epiphany. Instead of looking out of the metaphorical window, hoping to see prophets on donkeys arriving in the form of external consultants, he and his team would, instead, go down to the factory floor and explore what was going on, or more to the point, what was not going on. It soon became obvious that the employees had little emotional connection with the survey questions; they couldn’t see an outcome linked to the input; and the whole organization had become, paradoxically, addicted to, and dismissive of, the yearly results.

Jack and his team decided to demote the one-size-fits-all consultant emphasis on the four key drivers (which nobody really understood anyway), and instead, focus on a bottom-up approach. They empowered employee work teams to describe and explore the challenges that they believed were key in order to have a best place to work. The employees knew very well that they didn’t need a lovely-dovey feel-good exercise, but to focus on a place where the real work of facing the future could be accomplished. Within a year, they had drained the swamp and gained a clearer view of the landscape. The employees felt listened to and safe to innovate, which they did in many key areas very quickly. “Surveys are the crack cocaine of marketing and leadership,” Jack concluded. “We love quantitative data! It’s deterministic and certain! The light is red, or it’s green!” It does just enough to alleviate the pain in the system by distracting people and convincing them that they are taking action. However, the problem with statistics, he said, is that people are overwhelmed by all the data. It’s not alive, or it is only active in specific silos. It does not speak to people’s hearts. How do you join it all up? How do you know what you don’t know? What is missing?

Jack had come to understand that as CEO, he needed all the data, including what is not captured in a survey: the employees’ hopes, fears, and fantasies. He joked that it is like looking for the bathroom in the middle of the night. If you can see a sliver of light escaping under the door, then you know you are heading in the right direction. If you can find that door, then you are in the light and you can get down to business. Staying tuned to less-visible dynamics in the organization, he concluded, is like being able to see the light under the door.

Jack is in good company. An increasing number of businesspeople have come to realize that the use of systems-psychodynamic concepts can provide greater insight into organizational challenges at all levels. This perspective renders less-visible realities more accessible and worthy of interest.10 In addition, it offers novel and often startlingly original insights.11 In sum, systems-psychodynamics “represents arguably the most advanced and compelling conception of human subjectivity that any theoretical approach has to offer.”12

As Jack discovered, this approach is particularly adapted to making sense of periods of disruption during which emotions resonate, echo, or are baffled and dampened, within individuals and among the various levels of an organizational system.

The Five Premises of the Systems-Psychodynamic Approach

The systems-psychodynamic worldview encompasses dynamics that can be imagined as moving from the outside-in (the system, including elements such as the organization, the industry environment, and the economic climate), within groups (the interpersonal, from two-person dyads to large groups), and from the inside-out (the intrapersonal: individual, internal). It illuminates and informs studies and interventions in real-world contexts and organizations; it is not limited to theory. It describes and facilitates emotional forces and transition, and therefore it is particularly relevant in the context of crisis and change. It informs us: There is a rationale behind every human act—a logical explanation—even for actions that seem irrational.13 The five fundamental premises of the systems-psychodynamic approach are summarized below.

The First Premise: The Influence of the Unconscious on Daily Life

Though hidden from rational thought, the human unconscious affects (and in some cases even dictates) conscious reality. People aren’t always aware of what they are doing—particularly in the context of relationships—much less why they are doing it. Internal forces—feelings, fears, desires, and motives—lie outside of conscious awareness, but nevertheless, they are present in the form of “blind spots” that affect conscious reality and even physical well-being. These forces may be inaccessible within an individual to the extent that both self and others are blind to them, or they may be visible to others, but remain hidden to the self. Blind spots may be glimpsed in archetypal imagery that reveals the deepest levels of the psyche, where fantasy comingles with the “truth” of the world that is accessible through consciousness.

The Second Premise: We Are All Products of Our Past

Human development is an intrapersonal and interpersonal process. We are all products of our past experiences, including those from early childhood. As adults, these experiences remain in the form of engrained patterns of behavior, although we are not always consciously aware of them. These patterns influence many aspects of life, such the way we form relationships, or the way we defend our personal values and beliefs.

The Third Premise: We Are All Regulated by Emotions

Nothing is more central to who a person is than the way he or she regulates and expresses emotions. Emotions color experiences with related (transferential) positive and negative connotations. Emotions also form the basis for the internalization of mental representations of the self and others. As a whole, therefore, emotions—in terms of regulation or expression—influence behavior and choices.

The Fourth Premise: Groups and Individual Dynamics Are Interrelated

Groups are subject to dynamics that arise from a collective of individual needs and motivators. These out-of-awareness dynamics arise from intrapersonal forces (existing within an individual, including past experiences, blind spots, emotions, and attachment patterns), as well as interpersonal forces (existing between or among people, including dynamics such as collusion and task orientation). Over the lifetime of a group, the intrapersonal and interpersonal forces will continually interact, and as a result will influence emotions and behaviors.

The Fifth Premise: Systems Are Also Subject to Unconscious Dynamics

Human behavior may be considered as a symptom, as well as a cause, of systems dynamics. All systems—which include by definition organization systems—are subject to irrational forces and may have their own blind spots. The system exhibits, and may act according to, the unconscious needs of its members.

To sum up, the conceptual framework of the broadly integrative systems-psychodynamic perspective offers a practical way of uncovering additional data about how leaders and organizations function: (a) from the psychodynamic or inside-out position,14 (b) within the “middle” position of groups or teams,15 and (c) from the outside-in, or systems, position.16 As an applied methodology, the systems-psychodynamic epistemology “does not call for an abandonment of other organizational theories, but in many instances it supplements, qualifies, modifies, deepens, tests, and queries their arguments.”17 The systems-psychodynamic approach demonstrates more effectively than other conceptual frameworks that individuals are complex, unique, and paradoxical beings who differ in their motivational patterns. At the same time, this approach places human behavior in a relationship with the context in which it arises.

From the systems-psychodynamic viewpoint, organizations can be considered as systems that are “constructed, lived, and managed by individuals, each of whom has specific capacities and a specific unconscious.”18

Therefore, picking up a systems-psychodynamic lens helps us understand how the internal forces within one individual (the leader, or any other person) can ripple across to the edge of the organization. It also helps us to see how the ecosystem of the organization can seep into and color the psyche of the individual. In particular, this stance allows us to interpret what might appear to be human weakness as, in fact, a different form of rational behavior. Notably, the forces at play behind “irrational resistance to change or the incapacity to react in a crisis situation” become more visible.19

The Structure and Organization of This Book

We set the stage with the story of an organization—a system—in a “slow motion” crisis. In the next chapter, we go deep into the emotional heart of an organization in transformation. Next, we move to the middle ground, exploring the interrelatedness of individual leaders and the people around them. In a nuanced and counterintuitive approach, we present multifaceted stories of how toxic leadership arises from, and may be the cause of, crises in organizations. In the final chapter, we bring the focus to the intrapersonal level of systems-psychodynamics. As a way forward, this chapter shares a process for opening a reflective space that supports personal adaptability and recovery from crisis and change.

Two System-Level Chapters: Organizational Blind Spots and Idealization

Psychodynamic perspectives can be applied, by analogy, to organization systems: just as every neurotic symptom has an explanatory history, so has every organizational act; just as symptoms and dreams can be viewed as signs replete with meaning, so can specific acts, statements, and decisions in the boardroom. Organizations can develop blind spots; they can foster or deny collective memories.20

From a systems point of view, the repetition of certain phenomena in the workplace suggests the existence of specific motivational configurations. Organizational blind spots, for example, are described as mechanisms that enable organizations to remain committed to unworkable strategies. The formation of organizational blind spots is the result of a dual process: “fueled by unrealistic policies emerging in response to unconscious social demands, […] blind spots are enabled by defense mechanisms (for example, splitting, blaming, and idealization) that play a role in maintaining commitment to unsuccessful strategies.”21

Organizational blind spots, by definition, are difficult to see. In Chapter 2, Theo van Iperen brings to light a challenge that frequently remains out-of-awareness in organizations: cumulative crisis. Abrupt, acute crises are painful, visible, and hard to ignore; they generate a focused and rapid response. However, a cumulative crisis develops more slowly, through self-inflicted, deteriorating, and unexplored underperformance, most frequently caused by a legacy of mismanagement and/or poor decision making.

Most crisis or change-oriented interventions are designed to meet acute challenges and redress a threatening situation as quickly as possible. Strategy is developed and mandated at the top and cascaded down. However, van Iperen argues that managing a cumulative crisis requires a fundamental and holistic reorientation of the organization.22 In his chapter, he deconstructs five cases of successful recovery from slow motion crises, among which the common denominator is an unusual bottom-up restructuring approach. He reports that further testing showed that the bottom-up approach is a valid model for developing a comprehensive corporate recovery strategy.

Chapter 3 takes us deeper into the secret life of organizations, complementing and developing our understanding of organizational blind spots. In “Reimagining Organizations: The Stories We Tell,” James Hennessy recounts the emotional life—the memories and the fantasies—of a venerable, conservative organization that must come to terms with its past while environmental forces propel it into the future.

Hennessy demonstrates that while we do not usually think of organizations as generators and repositories of profound remembrance and longing, paying close attention to nostalgia and postalgia is also a valid method for understanding the existing state of an organization. Nostalgia and postalgia are usually thought of as being related to the way a person perceives the present as being unsatisfactory when compared with an idealized past or future. In psychological terms, such idealization can be employed as an anxiety coping mechanism.23 This involves the attribution of inordinately positive qualities to things—such as memories, future visions, situations, or people—which actually house hidden anxiety.

Asking questions about nostalgia and postalgia, Hennessy provides a tremendous amount of data about employees’ perceptions and feelings. In particular, crises can generate a particular mode of idealization called “chosen glory” within organizations. This refers to a shared mental and emotional representation of an event perceived as a triumph over adversaries or a calamity. The story is repeatedly cited to bolster a group’s self-esteem, becoming part of an organization’s identity, and passed on to succeeding generations of employees.24 There may be little interest within the organization in considering the entirety of its actions with respect to past crises—for instance, how the organizational system itself might have, in fact, contributed not only to their “glorious” resolutions but also to the creation of the original challenge. In periods of disruption, Hennessy concludes, idealization of past and future, housed in influential organizational stories, is of great significance.

Two Group-Level Chapters: Perpetrators and Victims

Systems-psychodynamic theories related to group dynamics bring us to a tighter focus on the middle ground in organizations. The key concepts here add an interpersonal frame to the systems dynamics outlined in the previous chapters. Focusing analysis at the group level, it becomes apparent that behavioral patterns may also arise from the collective unconscious of the group itself, as well as from the individuals of which the group is composed.

Organizations are collections of relationships in smaller, formal or informal groups, in which visible or hidden group dynamics are always in play. From this perspective, human behavior—individually and collectively—is seen as a symptom, as well as a cause, of organizational dynamics. “Although the vector of influence goes from the system to the individual, the latter is never passively molded by impersonal collective pressures. On the contrary, […] individuals often collude in creating them and keeping them in place.”25 This is how toxic leader–follower situations are formed, denied, or tolerated—and exacerbated in times of stress and crisis.

For example, while retaining a cognitive focus on change objectives, a leader may miss or ignore the emotional suffering of individuals, or of teams, or (last but not least) himself or herself. When group leader’s silence, passivity, or lack of response is a result of his or her own emotional paralysis or uncontrollable anxiety, this is likely to aggravate the group’s emotional distress. Group interactions may become flooded with overwhelming emotion; attempts at survival will replace constructive progress.26 Everyone feels the resonance of suffering, but it is difficult to articulate, partly because it seems impossible to resolve.

As a consequence, particularly in times of crisis, people may unconsciously engage in destructive relationship behaviors in an attempt to reduce chaos and stress. Paradoxically, toxic leader–follower relationships may develop and even be perceived as normal. Three typical dysfunctional leader–follower relationship patterns are narcissistic leadership, identification with the aggressor, and folie à deux.

Narcissism can be labeled as either constructive or reactive, with excess narcissism generally falling in the latter category and a healthy degree of narcissism generally falling in the former.27 Constructive narcissists tend to be relatively well balanced; they have vitality and sense of self-esteem, capacity for introspection, and empathy, while reactive narcissistic leaders become fixated on issues of power, status, prestige, and superiority. The result is that disposition and position work together to wreak havoc on reality testing, and the boundaries that define normal work processes disappear.

Healthy narcissism is a good thing in a leader. It underlies the leader’s conviction about the righteousness of his or her cause and position. Such a leader inspires loyalty and group identification. Although it can be a key ingredient for driving change, narcissism can also become a toxic drug.

When a leader is perceived to have the power to inflict mental and physical pain, some followers may resort to the defensive process known as “identification with the aggressor.” To protect themselves against possible aggression, they unconsciously mimic the aggressor’s behavior, transforming themselves from “those threatened” to “those making threats.”28 Inadvertently, they may share the leader’s eventual guilt about actions taken—guilt that can be exculpated through designating “villains” or scapegoats on which to project everything the group is afraid of.

Taken even further, some leader–follower collusions can be described as “folie à deux,” or shared madness, a form of mental contagion.29 In this case, a leader’s delusions—for example, denial of a crisis or flight into manic activity—become incorporated and shared by other healthier members of the organization.

Collusive leader–follower relationships like these, with their induced lack of reality testing, can have various outcomes. In extreme cases, the outcomes of narcissism, identification with the aggressor, or folie à deux can lead to the self-destruction of the leader and the demise of the organization. The implications of the dark sides of leadership and followership may be amplified in a situation of crisis and change. No leader is immune from taking actions with destructive consequences and no follower from being an active participant in the process.

In Chapter 4, Fernanda Pomin addresses the topic of toxic leadership and the complexity of corporate leader–follower relationships. Narcissistic leadership, a topic that was until recently taboo and is still little understood, was the focus of her research. As a specialist in leadership development, she has encountered narcissists and witnessed the damage they leave in their wake. She also knows that many people in an organization see only the advantages of narcissistic leaders. In her study, rather than diagnosing the problem or vilifying the narcissist, she takes an unusual, systems-psychodynamic entry point: the experience of subordinates who perceive their bosses as narcissists.

Her research suggests a path to recovering a sense of agency for subordinates in this situation, including alternative strategies of control and influence over their own professional context. She also reminds us that although narcissists may appear confident and powerful, they may be struggling with low self-esteem and vulnerability themselves. Wisely, she advises us not to shy away from our own dark side—to seek within ourselves the seeds of narcissistic behavior, for better or for worse.

In a juxtaposition of perspectives with Pomin’s research, in Chapter 5, Ross Emerson examines how the challenges of crisis and change may impact the well-being of leaders. In particular, he considers how top executives may be vilified, with blame and scapegoating cast upon a named individual, rather than on the function or the role. When the leader becomes the focal point for all the rage and distress that the greater context has unleashed, little consideration is given to the impact on that person. In his chapter, Emerson asks: “What happens to leaders—at the conscious and unconscious levels—when they are vilified?” The perception of being vilified—irrespective of actual behavior—can bring shame, trauma, and emotional scarring. Without pronouncing judgment, Emerson brings to the fore the importance of identity restructuring: a process through which an individual can reappraise, recreate, and move on—another form of individual agency and sensemaking.

A Final Intrapersonal Chapter: Know Thyself

The depth of the effect on senior leaders in the face of crises and change may not be fully understood for people who have not experienced the turmoil of organizational life. In Chapter 6, Ricardo Senerman writes from his own experience as a CEO and board member of several organizations. He has a public presence, feels public scrutiny, and is not immune to the stress and anxiety that comes with these positions. He wondered if a combination of methods for stress management and well-being might work as a simple but effective form of self-therapy for busy executives. Would he find some measurable sense of relief in stress symptoms, and meaningful insights about his own inner life? He settled on a study of interoception—the messages that the body sends related to emotions, such as sweating when you are nervous—and expressive writing (EW).

Senerman reminds us that all of us are aware of some of our thoughts and feelings, but a vast, unconscious part of our emotions and impulses remain out-of-awareness, blocked by our own anxiety and defenses. And yet, emotions remain influential, and as Senerman shows, they may be accessed and explored. In his action research study, Senerman developed a process for self-reflection that he tested on himself, experiencing and recording the merits and difficulty of a deep dive into one’s own psyche. He writes, “a soft, clear conversation among several parts of me and even others started to take place.”

Senerman’s work is aligned with the intrapersonal field within the systems-psychodynamics. The intrapersonal encompasses everything which is inside us, known or unknown. Our inner life may appear in patterns of behavior or articulated through somatic symptoms or emotions.

One of the core concepts of the psychodynamic paradigm considers these patterns of behavior to be related to an individual’s “inner theater.”30 Each one of us has an inner theater filled with people who have influenced, for better or worse, our experiences in life. These early experiences contribute to the creation of response patterns that in turn result in a tendency to repeat certain behavior patterns in other contexts, with different people. Though we are generally unaware of experiencing “transference”—the term given by psychologists to this confusion in time and place—we may sometimes relate to others as we once did to early caretakers or other important figures.31

The basic “script” of a person’s inner theater is determined by the way the inner theater evolves through developmental processes.32 A key concept here—containment—relates to the ability of the caretakers to provide good-enough presence. Good-enough containment does not prevent all frustration and fear, but it does help the baby (and later, the adult) to accept and tolerate ambiguity and anxiety.

Within the inner theater, certain themes develop over time—themes that reflect the pre-eminence of certain inner wishes that contribute to our unique personality style. These “core conflictual relationship themes” (CCRTs) translate into consistent patterns by which we relate to others.33 Put another way, our early experiences and basic wishes color our life scripts, which in turn shape our relationships with others, determining the way we believe others will react to us and the way we react to others.

We take these fundamental wishes—our CCRTs—into the context of our workplace relationships. We project our wishes on others and, based on those wishes, rightly or wrongly anticipate how others will react to us; then we react not to their actual reactions but to their reactions as we perceive or interpret them. (“I suspected he didn’t like me, and sure enough, his actions show I was right.”) Unfortunately, the life scripts drawn up in childhood on the basis of our CCRTs often become ineffective in adult situations if we are not aware of them. The desire to develop self-awareness, as Senerman shows us, brings with it a certain degree of agency in how to act.

“If You Are Afraid of the Dark, Turn on a Light”

When conditions are stable in organizations, the saying goes: “statistics are enough.” However, a purely rational-structural way of looking at organizations has never been a sufficient framework for understanding change in organizations. When everything goes crazy, we need the hidden data that the systems-psychodynamic lens reveals. The field of organizational studies is warming toward an appreciation of the contribution of the systems-psychodynamic approach to understanding crisis and change in the literature streams of leadership, critical management, change management, and organization behavior.

Unfortunately, this approach is often viewed by executives as something that appears glorious in theory, but impossible (and dangerous) to engage within the real world. For many leaders and observers of organizational life, the only thing that matters is what we see and know—in other words, what is tangible and measurable. It becomes downright frightening when the change spotlight is turned on the executives themselves, and they become aware of their own lived experience. Psychological defenses such as denial—at the individual, group, or system level—are there for a valid reason. They protect. But what is excluded from conscious awareness has, paradoxically, the strongest effect on behavior. In addition, whether we admit it or not, we take it all—emotions, transference reactions, and out-of-awareness blind spots—with us to work.

Our purpose with this book is to show that leaders and followers in organizations can effectively manage adversity by tapping into systems-psychodynamic concepts, in ways that are pragmatic and applicable. The chapter authors bring us much richer and deeper insights into the “why” behind thorny organizational dilemmas. In the end, they show us that, if we explore the “why,” we can at last advance toward “how”: pragmatic and sustainable options for change.

Businesspeople can indeed conduct systems-psychodynamic research and also put this approach into practice in organizations. All of the chapter authors are not only senior executives or organizational consultants but also graduates (with distinction) of INSEAD’s Executive Master in Change (EMC) program. The chapters are drawn from their original MA thesis research. The contributors provide us with real gifts: insights and renewed energy to change the way we live in the world of work.