My successes

PEPs/ISAs

I have included in this chapter PEPs/ISAs and takeovers because many of my successes have been by way of takeovers and many of these have also been ‘sheltered’ – free of capital gains tax – within my PEPs/ISAs, thus there is an obvious inter-relationship. The FT article in December 2003 on me becoming a PEP/ISA millionaire, ‘How I made £1m from £126,200’, is fully reproduced at the end of this chapter, together with the linked Q&A, ‘How can I do what he’s done?’. The chapter works through my major successes on a chronological basis, culminating with a number of shares I currently own where I sit on large profits.

Chapter 3 details some of my initial activities when I was operating with very little capital. In the latter 1960s, as my resources grew slightly larger, I doubled my money on Brock Alarms, a ‘long-term’ profit of £217. (In those days capital gains tax differentiated between ‘long-term’ and ‘short-term’ gains, something I would like to see today.) Similarly, £177 on Slater Walker and a ‘short-term’ profit of £58 on supermarket new issue Amos Hinton.

By the 1970s I was investing larger sums: a profit of £400 on a £7,000 stake in holiday camp Pontins; £1,230 on a £4,400 holding in British Vita; and more than doubling my money on a £6,300 holding in car care products Holt Lloyd. It was in 1976 and 1977 that I made my first ever investments in overseas trader Paterson Zochonis, now PZ Cussons, and North West contractor/developer Pochin’s respectively – I refer to both in Chapter 4 covering family PLCs. More later on as I still hold both.

Takeover successes

This era also saw two takeover successes: a 25% profit on a £10,000 holding in Madame Tussauds in 1978, after a hard-fought battle between Pearson and ATV, and in the same year more than a 100% profit on bakery powders/specialist foodstuffs Goldrei Foucard. I was very fortunate here: I bought in June 1978, then went to the AGM of this family-controlled PLC in a London suburb, discovering that there was no apparent family succession. Lo and behold, by October an agreed takeover was announced.

This was an early example of a proprietorial or family PLC selling out. Over the years many other similar companies have succumbed to bids where for a mix of reasons the controlling family decided to sell and realise the worth of their holdings. Often family shareholders not connected with the company in an executive capacity would rather realise a slug of capital to do their own thing – buy a better house, a farm, a yacht – than receive perhaps an annual dividend. And who can necessarily blame them – we only have one life.

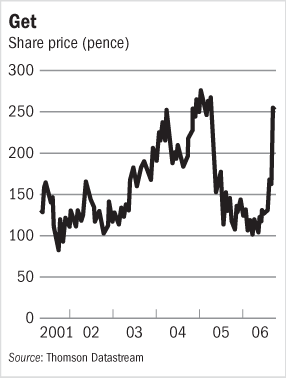

I made fairly substantial profits on three larger family PLCs on holdings that I had patiently built up – Stockport bell chimes manufacturer Friedland Doggart, bought by MK Electric in 1985, small electrical appliances Pifco, taken over by Salton of the USA in 2001, and lights/switches/cable manufacturer GET by the French electrical group Schneider in 2006. The following two articles tell the stories of Pifco and GET in more detail.

Years of patience pay off with Pifco

The £50m takeover by Salton Group is good news for long-term investor John Lee

Although the £50m takeover of electrical appliances manufacturer Pifco by Salton Group of the US is very pleasing to me financially, its demise is tinged with regret as it marks the end of a long-term investment relationship.

Pifco is one of those companies that can be described as a safe haven for my savings; it is a “proprietorial” plc, where a family effectively has managerial and equity control, usually stewarding conservatively.

Many of these companies are characterised as being cash-rich. Over the years dividends are steadily increased and the value of the business grows. But the stock market capitalisation lags well behind – through a combination of its low profile and limited marketability – often perceived to be boring by whizkid fund managers.

I first bought Pifco in 1976, subsequently taking useful profits on four occasions. They were also my first Pep investment in October 1987 when, after a long search, I finally discovered Midland Bank Trust Co, which allowed me to “self select”.

Around half my current holding is historic, the balance being acquired in the latter 1990s.

I kept closely in touch with my investment through post-results announcements, phone discussions and AGM attendance – usually being the only attendee.

Pifco’s big coup was the acquisition of loss-making Russell Hobbs, turning it round in double-quick time. However, it was in the classic small company dilemma. It either had to acquire or ultimately would be acquired, particularly as there was no family succession.

Kenwood was in its sights for a long time, but in the end wisely decided not to overstretch itself and enter an auction following an Italian bid.

I visited early last year before an article of mine appeared in the FT headed “Unloved, unwanted, undervalued” and written with Pifco shares at 135p. I wrote: “Pifco is clearly worth much more than its £24m capitalisation. I would be fascinated to hear just what valuation a brand consultant would place on it – there is also a large cash pile likely to be around £12m by year end.”

During the early months of this year, the shares rose with “value” investor Fortress Finance steadily upping its stake to 7 per cent; then in April it was announced that it was in talks that could lead to an offer – a further bounce to £2.

I always believed that Pifco was worth nearer £3 than £2, and thus was happy with an agreed 276p. But even that was not a knockout price – a third party could enter the fray – so I bought a few more at 270p, there was no downside even with dealing costs.

While press comments referred to it as a “done deal” with 54 per cent “irrevocably accepted”, in reality, from examination of the offer document, only the directors’ 20 per cent was irrevocable. The balance had a “get out” in the event of another bidder offering 10 per cent more.

However, nobody else has appeared, so it is farewell my old friend at 276p. This represents a 150 per cent profit on cost for me, and as it was a significant holding, it’s an excellent start to the new tax year for both myself and my partner the Inland Revenue.

There is a loan note alternative, but I prefer to take the cash, pay the tax – a third of my holding is held within Peps and is therefore free of CGT – and move on. There are other Pifcos out there, so happy hunting. Stock market value always comes through in the end.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2001) Years of patience pay off with Pifco, Financial Times, 26 May.

© The Financial Times Limited 2001. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

My earlier article on Pifco (‘Unloved, unwanted and undervalued’) focused on its undervaluation and potential. Here I record its takeover by Salton of the USA, delivering me a handsome profit in 2001. However, I had held the shares since the mid-1980s – again patience paid off.

Patiently waiting for the end-game

John Lee

Over the years I have been on the receiving end of many profitable takeovers – indeed they, and the occasional management buyout, are invariably the end-game of my relationship with so many of my investments – rather akin to the passing of an old friend.

Of perhaps 40-plus existing small-cap holdings I would anticipate that broadly 80 per cent will have succumbed 10 years hence – probably 50 per cent within five years. In many ways one would prefer them to grow independently to become the mid-caps of the future. But the trend towards larger corporations in an era of increasing globalisation, the desire of family-controlled businesses to capitalise on personal wealth, perhaps because of the lack of family succession, and the frustrations with managing an unloved and undervalued plc, encourage takeover activity.

From personal experience the most profitable bids (in other words the biggest premiums on prevailing market prices) arise when a family controlled company is sold. Then comes the contested takeover with the management buyout a poor third, usually the lowest price that shareholders can be decently offered, leaving plenty in it for the buyout team and its backers!

For me the week of September 11 had it all; on Monday it was announced that family-controlled electrical products manufacturer/distributor Get had agreed a 260p cash offer from the giant French electrical group Schneider – a 73 per cent premium to the share price prior to bid talks being announced. Midweek came the news that the management of niche insurance broker Windsor was considering making a 52.5p offer – an 18 per cent premium to the prevailing price. And finally on Friday Biotrace, which makes contamination detection equipment for the food, beverage and defence sectors, rose 20 per cent on announcing that it had received a number of preliminary approaches.

My association with Get goes back to May 2001 when I made my first purchase at 157p following a visit to its large Midlands distribution depot where I met chairman John Joseph and financial director Michael Cohen. I bought more shares at between 117p and 203p over the next two years, mostly within my Pep, feeling that it was my type of solid well-stewarded business with every prospect of rising profits and dividends. All went well until 2005 when poor trading within their DIY sector and consequent high stock levels saw profits fall and a slashing of the dividend by over 50 per cent. I angrily clashed with them over this latter decision, believing it to be unnecessarily draconian, seriously damaging their credibility with investors. Sure enough the shares slumped to under 100p but I still had faith, buying more at 115p.

Unfortunately in March 2006 the company moved to Aim, the junior stock exchange, a very expensive decision for me as it transpired. I had to “buy out” the shares from my Peps at 103p (most Aim shares cannot be held in Peps or Isas) and thus I now face a thumping CGT liability on the 260p bid!

I started to buy Windsor in February 2002 at 22p after meeting chairman David Low at the company’s AGM, steadily increasing my holding with 15 further purchases up to 43p – again predominantly sheltered in my Peps and Isas. Two sales were made at 39p in 2003 and 56p in May 2005. Profits, dividends and the share price rose steadily in the early years of ownership but recently overall performance has been more pedestrian, leaving the price somewhat becalmed on a single figure price/earnings ratio.

I cannot believe that Low and his buyout team, who after all give professional advice to others, would announce a likely precise price of 52.5p if they had not already lined up their financial backing. This modest price could well be topped by a trade buyer.

Biotrace, my only Welsh holding, has been this year’s “find” and I have bought 13 lots at between 87p and 97.5p, all sheltered in Peps and Isas. I have written of the company as being significantly undervalued. 3M clearly agreed. This week the diversified technology company announced a recommended 130p per share cash bid for Biotrace – all very pleasing but – who knows? – other bidders may yet appear.

So all in all a very exciting week but the moral is clear: buy sound established profitable companies at the right price, put time into the equation and be patient. Value will always come through in the end.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2006) Patiently waiting for the end-game, Financial Times, 7 October.

© The Financial Times Limited 2006. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

Here we record the takeovers of GET and Biotrace, and the management buyout of Windsor. I would just like to emphasise and repeat the concluding sentences: ‘… but the moral is clear: buy sound established profitable companies at the right price, put time into the equation and be patient. Value will always come through in the end.’

Later on in this chapter I talk more about takeovers, how they arise, and the pros and cons from an investment standpoint.

In the 1980s I had many more successes than failures: textile group Coats Patons and cigarette manufacturer Rothmans (I would not buy a tobacco share today as a matter of principle), bought on very low single-figure price earnings ratios and good yields, both delivered £10,000+ profits; hostels/hotels Rowton nearly double that, and two early sales of PZ Cussons in 1981 and 1987 made profits totalling £25,000.

It was from gains like these that I was able to start building up some larger holdings. Local property company Trafford Park Estates (TPE) was a situation which caught my eye. As its name implies, it owned a substantial acreage of buildings, land, railway track, etc. in Manchester’s Trafford Park industrial area, very close to the Manchester Ship Canal and adjacent to Manchester United’s Old Trafford (TPE sold some land to the football club to facilitate ground expansion). The company was very conservatively run, the shares stood at a significant discount to assets, there were no controlling shareholders, and I was convinced that one day TPE would be taken over at a good price.

I first bought in 1990 at 62p, making 11 more purchases between then and 1996 at between 41p and 116p; some were made in my PEP. I used to follow TPE closely, reading all available comment and attending its AGMs. For some reason I sold a portion in 1997 at 140p and 168p. The takeover bid finally arrived one year later in 1998 at 190p from Irish property company Green. Unfortunately no other bidder appeared – a battle is ideally what you hope for at ever escalating prices – but here the first bid won the day. I had made my largest ever profit – a six-figure sum – of which two-thirds was taxable, one-third tax sheltered. The message is: ‘Stick to your convictions’ – don’t be tempted to get out early from a good value holding.

Over the years property shares have served me well. ‘Property has provided me with firm foundations’ below talks of the successes I have had with several property companies over the years, including TPE and the Leeds-based Ziff family’s property company, Town Centre Securities, owner of the Merrion Centre in that city. However, two rules: first, always buy property shares at a discount to net assets, and second, once again put time into the equation – be patient, your ship will eventually come home.

Property has provided me with firm foundations

John Lee

I first became aware of property shares 50 years ago, on reading an investment newsletter – I think it was written by a man called Beveridge – which my father used to receive. Beveridge extolled the virtues of Harold Samuel’s Land Securities – and I much regret never having tucked some away.

My first property holding was developer Edger Investments – named from the ED of Edwin McAlpine and GER of City solicitor Gerald Glover. My records don’t go back that far but I suspect my holding cost all of £100 – I cannot remember the outcome!

Over the years, I have bought and sold many property shares and been through several property peaks and troughs. Usually, I focused on lowly-geared plcs at a significant discount to assets – often finding this combination in family-dominated businesses.

While I have incurred one or two small losses – Warnford Estates in 1973–74 and Barlows in 1991-94 – property shares have served me well, which is not surprising given inflation and the general appreciation in property values.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Freshwater family’s Daejan Holdings going public. The annual report tells us that, in 1959, net assets equated to 29p per share. Today, that figure is £46.60, a 160-fold increase! Sadly, I didn’t buy until 2007, paying £41 per share, then £29 later that year and £27.50 in 2008.

The nearest I have come to a Daejan-like performance was with northwest building services company Pochins which, in recent years, was powered along by its property developments. I first invested in 1977 and then finally in 1984, with my average buying price being (an adjusted) 5p. The shares peaked at just over £4 in 2007 – I felt they were “toppy” and realised some at just under that figure. However, in the recent maelstrom, they have plunged to a current 85p – but still show me a 17-fold appreciation.

Another significant success was with industrial property owner Trafford Park Estates, which I bought on 12 separate occasions between 1990 and 1996 at 41p-116p. It was subsequently taken over by Green Properties of Ireland for 190p in 1998.

Other more modest successes included a 1996 purchase of London Industrial Group (later renamed Workspace), Peel Holdings – developer of The Trafford Centre – in 2000, Yorkshire small industrial estates owner Headway in 2001 (I remember getting lost in Halifax’s one-way system searching for one of its sites!) and London landlord Estates and Agency Holdings in 2004.

However, the Ziff family’s Leeds-based Town Centre Securities must be my all time yo-yo. I paid 64p in 1999 for a good yield and assets discount. By skilful management – including buying back half its equity – the NAV rose steadily, with the shares peaking at 653p in 2007. I sold some at 595p. The banking/property crisis then sent the shares crashing – I bought again at 60p in February 2009, selling three-quarters of this purchase at 182p in September – a trebling in seven months.

Today, I hold seven property stocks: Daejan, McKay, Pochins, Primary Health, Sovereign Reversions, Stewart & Wight and Town Centre. I regard them all as long-term “holds”.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2009) Property has provided me with firm foundations, Financial Times, 7 November.

© The Financial Times Limited 2009. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

Over the years I have done very well by investing in property shares, achieving some spectacular profits, but I always buy at a discount to net asset value. The rise and fall of Pochin’s is chronicled in Chapter 4.

More on takeovers

In family PLCs, takeovers tend to happen when there is a lack of family succession or there is a desire to realise wealth. In non-controlled PLCs, i.e. where there are no controlling or dominant shareholders who could dismiss a takeover approach out of hand, takeovers usually involve a larger company taking over a smaller one. These latter takeovers are usually driven by the pressures of globalisation, a larger PLC seeking to ‘take out’ a troublesome competitor or to acquire a new revenue stream through diversification, perhaps a shortcut rather than developing itself through organic growth.

Sometimes directors of companies seek a takeover as a means of delivering value to shareholders or sometimes they wish to cash in their shareholdings/share options. Many commentators see takeovers as frequently destroying value in the acquiring company – a tendency to over-pay, perhaps resulting in the buyer taking on too much debt. What can be certain, however, is that in a free capitalist society takeovers will continue, they are a fact of commercial life. Personally, I would prefer a company to remain independent, ideally increasing its profits and dividends year on year, and this is arguably in the national interest as well. A takeover usually coming in at a premium on a prevailing market price delivers a certain profit to shareholders in the short term, but maybe at the expense of larger longer-term gain. Many criticise the short termism of the City, but in my experience most major UK financial institutions do take a longer view, although hedge funds and similar are usually more focused on the short term.

There is a saying that a small cap stock is priced correctly only twice – on original flotation and on ultimate takeover; for the rest of its life it remains undervalued, thus offering the alert investor attractive buying opportunities. Over the years I have been on the receiving end of more than 40 bids, and only a handful have resulted in losses. Two I recall were large cap Cable & Wireless Worldwide – one of the Cable & Wireless twins – finally being put out of its shareholders’ misery by Vodafone, and AIM-quoted tiddler James R. Knowles, in specialist arbitration/claims services to the international construction sector, bailed out by a US competitor. Unfortunately I was a non-executive director.

It is impossible to be absolutely certain that any particular company will be ultimately taken over, but as a generalisation, a small profitable PLC providing specialist services or products, particularly with a recognised brand name, is almost always going to attract predatory eyes at some stage. Another reason for preferring small caps.

Profitable takeovers for me included Jarvis Hotels, Norscot Hotels and Trust House Forte in the hospitality sector, Cheshire Whole Foods and Joseph Stocks in foods, THB and Windsor in insurance broking.

Windsor brings a touch of class

John Lee explains how he discovered a nugget in the smaller companies annual reports

Casting my eye over the smaller company annual reports in the Investors Chronicle – as always I was looking for new opportunities. I didn’t spend too long on 7 Group – a “cash shell”, Ninth Floor – “security technology and football club owner” or TZI “African producer of paper, batteries and roses”. But what did catch my eye was insurance broker Windsor.

I looked more closely – steadily rising profits since a loss in 1997, a twice covered 5.5 per cent dividend yield, a price/earnings ratio of eight and the outlook described as “positive”.

Aware that insurance premiums had risen following September 11 with a consequent rise in brokers’ shares, Windsor looked interesting and somewhat undervalued.

Over the weekend I searched the internet for any recent announcements, directors’ share purchases and so on and carefully study my “bible” Company Refs. I found nothing negative – chairman and chief executive David Low’s shareholding is a substantial and constant 12 per cent, almost equalled by Abtrust with Jupiter having nearly 6 per cent.

By a fortunate coincidence the annual meeting was in London the following Wednesday – I had a luncheon engagement in the West End that day – but I might just be able to look in as there was a noon start.

By Monday morning I had decided to “buy” and put a toe in the water – a call first thing to my broker and then one to Windsor’s company secretary.

“Could I please have a copy of the annual report as soon as possible and what time does the agm start?” The answer to the latter was 10am. Although not usually a convenient time for me on this occasion it was perfect – I would definitely be there.

I decided to do more checking – and sought out anyone who knew anything about Windsor.

The company operates niche areas including sport and leisure, and professional indemnity. I found that friends running a large-scale visitor attraction used them and found them first class. But a fund manager I knew was aware that the executive team running the very successful professional indemnity business had an option to compel Windsor to “buy out” their substantial interest at any time – thus creating a degree of uncertainty in the minds of the investing community.

My annual report duly arrived in Tuesday’s post – I studied it carefully as I travelled by train to London that afternoon. Wednesday found me at the company’s Great Tower Street headquarters for the annual meeting.

I asked two questions during the formal meeting: on the re-appointment of the financial director – although he holds options does he plan to buy any shares as currently he owns none? Answer: No.

The chairman adds that the financial director is currently buying a house. Later – were the professional indemnity team “tied in” to continuing to work for Windsor in the event of them exercising their “put” option? Answer: a complicated issue but in all probability “Yes”.

I lingered afterwards over coffee talking to David Low and his team and I got the feeling of a tightly run ship with further growth and expansion ahead – not fully recognised in the then £12m capitalisation at 22p.

I didn’t depart until noon – only just making my luncheon engagement! It had been a whirlwind romance – I have subsequently added to my holding at a slightly higher price – the market is tight. Windsor now sit snugly in my portfolio – another stock “put down” for the future.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2002) Windsor brings a touch of class, Financial Times, 2 March.

© The Financial Times Limited 2002. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

Here I tell the story of how I first alighted on insurance broker Windsor through reading an article in Investors Chronicle and how I then checked it out. AGM attendance provided useful confirmation. While the ultimate buyout was profitable, it was not a bonanza – buyouts rarely are as Boards/management obviously pay the minimum price they can get away with.

Other takeover successes included Parkdean in caravan parks, Gibbs and Dandy in builders’ merchants, Broadcastle, Hitachi and Wintrust in specialist finance, Breedon in quarrying, Ben Bailey in housebuilding; thankfully just before the 2008 subprime crash, Sovereign Reversions and Peel Holdings in property, Refuge in insurance, and Wyevale in garden centres.

Exchange of ideas

Capital Pub is a more recent success story and an exceptionally profitable one. I first heard of it at an investment dining club of which I am a member. We operate a small, somewhat speculative portfolio, discuss investment ideas, and dine very well and convivially, usually at the Turf Club in London. Being a member of an investment club or similar is to be encouraged. Here we have a dialogue for mutual benefit where investment suggestions are made and a private investor finds thoughts and ideas considered and tested by their peers.

While many investors operate on their own – certainly in the ultimate making of decisions – most have a number of investing friends, as I have, among whom ideas and thoughts are exchanged, preferably over a good meal. A number of groupings of private investors have been formed in recent years. For example, www.sharesoc.org, with 3,000 members, takes up investors’ grievances, and www.mellomeeting.co.uk, with over 800 members, arranges regular company presentations.

Capital, I learned, was building up a chain of quality freehold London pubs, significantly upgrading the food offering, and clearly benefiting from London’s buoyant visitor economy. It sounded like my type of investment – worth investigating further. I lunched with Board members at their valuable Ladbroke Arms Hostelry and they impressed me as a focused and experienced management team.

I first bought in December 2009 at 70p, adding more the following year at 76p. I followed their progress with keen interest. It seemed obvious to me that at some stage Capital would be a very attractive add-on for a larger pub chain. Midway through 2011 it happened. Press reports indicated predatory interest. Finally a recommended bid came in from brewers Greene King. I sold my holding at just over 230p for a near six-figure profit. As Capital was an AIM stock (quoted on the Alternative Investment Market) it had been regrettably ineligible for my ISA. Thus a 28% share of my profit went to HM Revenue & Customs, but I must not be ungrateful – Capital had delivered an excellent profit in a far shorter period than usual.

Taxing issues

I now turn to the importance to me of my PEPs/ISA opportunities and how I have used the exemption from income tax and capital gains tax to advantage. The Thatcher government, of which I was a member, introduced personal equity plans in 1987. Individuals were allowed to invest an amount of money each year in shares (the limit changed on a number of occasions). You could either choose personally which holdings to invest in – I always did – or have your shares selected/managed by a PEPs manager. I viewed all this as an outstanding investment/savings opportunity.

For the next 17 years I invested the maximum allowance every year, re-investing all dividends and tax credits received. The shares I bought had to satisfy all my normal criteria, but given the dividends’ tax-free status, they assumed even greater importance. By December 2003 I had invested a grand total of £126,200, plus dividends re-invested, and at that time I wrote an article in the weekend Financial Times disclosing that the value of my PEPs/ISA portfolio had reached the magic £1 million. (The Labour government introduced ISAs to replace PEPs, but for all practical purposes they are essentially the same.) My full PEPs/ISA portfolio – reprinted in this article – was published, disclosing a value of £1,015,843.65. It included PZ Cussons, S&U, Nichols, Treatt, Christie Group, Air Partner and Primary Health Properties, most of which I still hold. However, Nichols and Christie moved from the main market to AIM, thus becoming ineligible for ISAs, so I had to ‘buy out’ these holdings; however, now that AIM stocks are eligible for ISAs, Christie have gone back in!

I continued to invest annually in my ISA for a number of years post-2003, but more recently with the overall value of my ISA thankfully moving further ahead I have stopped topping it up; clearly, as the ISA rose, a limited annual allowance became less relevant. My ISA is administered by the well-regarded firm of James Sharp in Bury, Greater Manchester, very much an old-style, traditional broker.

My basic principles

I now come to what in many ways is the raison d’être for this personal story and the main message that I wish to convey: that a substantial portfolio can be built, brick by brick, by applying common sense and basic investment principles. But it does take time! Hence ‘how to make a million – slowly’.

I think the best way to demonstrate all this is to look at my holdings in May 2013 and see when I first bought into them. The article ‘Proof I’m in it for the long haul’ clearly emphasises in the summary, ‘Through the years’, why I regard myself as a serious long-term investor.

Proof I’m in it for the long haul

John Lee

For me, a private investor is someone who buys into a company, stays with it, and hopefully sees it prosper. A trader who regards the stock market as the equivalent of a short-stay car park – in and out as quickly as possible – is certainly not an “investor”.

As someone in the former category, I thought it would be interesting to look into the duration of my shareholdings.

As a starting point, I took my first purchase of a serious current holding: toiletries group PZ Cussons, which I bought in 1976.

In 1977 came North West building services/property developer Pochin’s; in 1994 I bought into both short-term lender S&U and pharmaceuticals distributor United Drug. The table shows my portfolio by year of purchase.

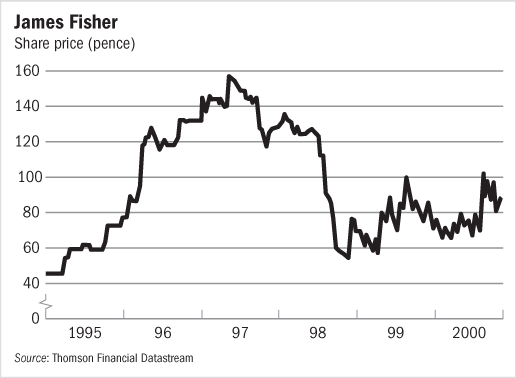

Many positions have been added to over the years, always with a view to the long term. Pleasingly, the majority are in positive territory – some spectacularly so – eg. PZ Cussons, with James Fisher, Nichols and Fenner appreciating substantially.

Pochin’s has been a real roller coaster – rising to nearly £4 in 2007 – thankfully I sold some then – before sinking to a current 23p on joint venture property development horrors and concrete pumping losses.

Thankfully, my only real dog, Cable & Wireless Communications, is off the bottom.

These days I rarely make big changes, occasionally initiating a new position while benefiting from the healthy dividend flow. I tend to reinvest dividends; in my Isa, which houses 14 of the 30 holdings. All dividends are used to buy more shares.

I rarely sell out of shares completely, partly because many of my holdings aren’t very liquid, and partly because I don’t want to pay capital gains tax (shorn of indexation relief) at 28 per cent. But I often add to them; last month I added more Air Partner, which has loads of cash and offers a 6.5 per cent yield.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2012) Proof I’m in it for the long haul, Financial Times, 6 October.

© The Financial Times Limited 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

Here is further evidence of my long-term investing and the exercise of patience. Most of my holdings tend to be long fused, i.e. usually I hold them for a number of years before they hopefully ‘explode’ into profit. Some have already delivered sizeable gains, like PZ Cussons, James Fisher, Delcam and Fenner. However, for Charles Taylor, Christie, Concurrent Technologies, Quarto and Vianet, hopefully their best is yet to come.

I have referred to my two long-held holdings PZC and Pochin’s earlier in Chapter 4. PZC is a ‘core’ holding, an outstanding success story which has done me proud. Today it is one of my most valuable holdings, having delivered substantial capital and income growth.

One thing that all analysts and commentators accept is the importance of dividends and dividend growth and where possible, as in an ISA, the tax-free reinvestment of dividend income. Unfortunately, PZC is not in my ISA, therefore I receive and pay tax on its dividends. However, I am currently receiving a near-annual rising dividend yield of approximately 38% on my original cost price.

My other current 1970s’ purchase, Pochin’s, has sadly become a problem child in recent years and there is a question mark over its future. Currently it pays no dividend and has fallen dramatically from its peak. Even now though, the ‘rump’ is five times my original cost price and earlier sales have recouped more than the amount I invested. Nevertheless, at peak, in the boom times, my Pochin’s holding alone was worth north of £1 million, but sadly that is history.

I held both short-term lender S&U and Irish/UK pharmaceutical distributor and packager United Drug for nearly 20 years. I have taken profits on the former family PLC over the years. My cheapest purchase was 290p in 1995, today they are around £13; the latter have appreciated six-fold.

Treatt, in flavours and fragrances, has been with me for 14 years. I have bought into it no less than 25 times, mainly in my PEPs/ISA, having paid between 153p in 1999 and 280p for my last purchase in 2006. Today – August 2013 – it is 630p, so a very nice gain. I have visited its Bury St Edmunds’ base on two or three occasions and I have had numerous conversations with former chairman Hugo Bovill, and other executives. Its US division, started from scratch, is now probably more important than its UK base. It has also paid a steadily rising dividend over time. I always believed that Treatt was a very valuable business, unique to the stock market.

I briefly touched on marine services James Fisher in Chapter 7 because I wish that I had retained all my Fisher shares and had stayed aboard for the whole voyage rather than shedding shares at different ports, because Fisher has been a great success story (see ‘All aboard for growth at the new Fisher’ opposite).

All aboard for growth at the new Fisher

John Lee describes the attractions of investing in a traditional shipowner which is evolving its fleet into niche activities

My holiday reading this year included Around the Coast and Across the Seas by Nigel Watson. a fascinating history of shipowner James Fisher.

The company was founded in 1847, its growth built on the export of iron ore from Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria. A stock exchange flotation came in 1881.

The circular enticing potential investors with news of a new ship costing £1,800 boasted: “We have had two of this class of vessel built lately and both have done and are doing well. We shall be glad to put your name down as a shareholder”.

I wonder what today’s regulatory authorities would make of the rather thin prospectus.

My first encounter with the company was in the early 1970s when the Manchester Dry Docks Company, where I was a director, repaired a number of James Fisher vessels. It was not until this year, however, that I became a Fisher shareholder.

The company is unique in a number of ways. It is the UK’s last quoted true shipowner. It expects to pay a tax rate of only 5 per cent for the foreseeable future as a result of the new tonnage tax regulations. It donates money to both the Conservative and Labour parties.

The Fisher family still retains an interest of about 25 per cent, owned through a charitable foundation, but the management is in the hands of David Cobb, a canny Scot with long experience in shipping. He has been at the helm since 1994 and is moving the fleet away from its traditional small tanker and dry cargo operations into rather more profitable niche activities.

For example, following excellent results from its cable layer Nexus, two more vessels have been purchased and are being converted in Croatia for delivery early next year.

They have been chartered for a minimum of five years by International Telecom USA, guaranteed by its parent General Dynamics, the US industrial group.

This represents a serious investment for James Fisher. The £40m cost is almost equal to the group’s stock market value and compares with a net asset value of £70m. Fisher could be a surprising beneficiary of the global telecommunications boom.

Other specialist ships in the fleet include RFA Oakleaf, chartered to the Ministry of Defence, and New Generation, a roll-on-roll-off heavy lift vessel.

There is also a diving support ship, a joint venture with Cammell Laird. Two other James Fisher vessels carry irradiated fuel rods between British Nuclear Fuels and Japan.

The group has a business based in Aberdeen serving North Sea oil and gas production facilities. This is part of an Underwater Services division.

Fisher also manages an aircraft spares facility at RAF Sealand near Chester, and is the preferred bidder in a consortium with Bibby and Andrew Weir for a 20-year contract to operate six roll-on-roll-off ferries for the MoD.

The “new” James Fisher being shaped by David Cobb is therefore moving away from its roots as a traditional coastal shipper. That said, the transformation will take time. There is still a 30-strong James Fisher fleet of small tankers and dry cargo vessels. The latter are unprofitable.

Pre-tax profits sank from £8.7m to £3.8m in 1998, reflecting closure costs, but recovered to £6.2m last year. The performance of the shares has reflected these changing fortunes – hitting a peak of more than 150p in 1997 before falling back to a low this year of 63.5p.

Several factors persuaded me to invest. The minimal tax charge suggests scope for further dividend increases. The pay-out was increased by 16 per cent in 1999, and by a further 10 per cent at the interim stage in September.

The price-earnings ratio is very low at about five times this year’s forecast earnings – despite the likely boost to profits from the two new cable layers over the next few years.

Even allowing for the fact that forecasts for this year have had to be trimmed – to take account of increased running costs arising from higher oil prices – the shares are hardly expensive. In the meantime, the yield is a comforting 5 per cent.

Sure enough, the shares have climbed towards 90p since the summer, helped by occasional bid speculation. It seems a good time for medium to long-term investors like me to come aboard what is a rather special company.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2000) All aboard for growth at the new Fisher, Financial Times, 28 October.

© The Financial Times Limited 2000. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

We end with me boarding marine services James Fisher in 2000 on a ‘double five’ – a yield of 5% and a price earnings ratio also of 5. Here again one can hardly go wrong at these levels, but a unique combination of organic growth coupled with shrewd niche acquisitions made Fisher an outstanding success – a ‘ten bagger’+! I refer to Fisher in Chapter 7, ‘My mistakes’, because I took profits far too early. Easy to say this in retrospect – hindsight is a wonderful thing and never more so than in stock market investing.

I first bought in 2000, when the company primarily comprised a small fleet of coastal oil tankers, at 78p – more at 71p and 74p – but most acquired in 2000–3 at an average around 150p. I think people regard shipping as a rather staid sector, as I did initially. In fact, it has shown steady growth over the years, albeit with varying profitability through numerous shipping cycles. However, Fisher has steered clear of mainstream shipping, focusing on niche areas in marine services, such as sub-sea technology globally, and in the UK being involved in operating, at one time, our national submarine rescue service. It has grown organically and by numerous ‘bolt-on’ acquisitions, most of which have been successfully integrated.

Surprisingly, it would appear that no other PLC has copied Fisher’s strategy in the marine sector. However, it has not all been plain sailing for the company – an early foray into cable-laying vessels was an expensive failure – but overall there have been far more correct calls. Today Fisher shares hover around £11. Thankfully I retain a significant minority of my original holding; I show 14-fold appreciation on my purchases, with a current 24% dividend return on cost.

The fourth of my major current holdings after Nichols, PZC and Treatt is software specialist Delcam. A former stockbroking colleague mentioned this company to me years ago at a Christmas party, observing that it was spending £9 million per annum on research and development but declaring a bottom line of profit of only approximately £1 million.

I decided to investigate further and visit its Birmingham base. There I discovered a superb, conservative business, quietly developing its specialist software for the manufacture globally of large shapes. Delcam had built up an international operation, with staff and agents throughout the world, and was clearly highly regarded. It is still the only business that I have come across which has built accommodation and a conference centre for its overseas employees and visitors on the small industrial estate where it is headquartered.

I first bought in 2006 at just over £3, in total making 16 purchases between 225p and 420p. Along the way rated PLC Renishaw encouragingly subscribed for 20% of Delcam’s capital at £4 a share. In recent years the company has continued to invest substantially in R&D and developing overseas, but bottom-line profits have really started to come through and dividends have risen accordingly. The shares have recently touched £14.

Other noteworthy successes include Ilminster’s electro-optical laser specialist Gooch & Housego, which have quadrupled, and Birkenhead voucher redemption group Park, which have trebled, as have Redditch lighting manufacturer F. W. Thorpe – all AIM quoted. In my ISA, conveyor-belting manufacturer Fenner holds top spot, having risen six-fold despite falling back to the 350p level from a peak of £5.

All these stocks are still very firmly held. In almost every case they have achieved the double whammy which I referred to earlier: real profits growth plus a re-rating.

So, the overall message is to take the long-term view – in the words of St Augustine, patience is the companion of wisdom.

How I made £1m from £126,200

John Lee believes many investors are missing out on the benefits offered by tax-free wrappers

I’m glad MPs aren’t barred from benefitting from legislation they supported. If they were, I could be more than £1m poorer.

I have always been a devotee of the stock market and a disciple of long-term investment. So as Conservative MP for Pendle, and as a minister from 1983 to 1989, I firmly supported the creation of personal equity plans (Peps) by Margaret Thatcher’s government in 1987.

For the first time, Peps gave everyone the opportunity to build a fund of equity investments free from income tax and capital gains tax. It was obvious that this was a great opportunity for serious savers, but I suspect that few recognised the golden potential.

For the next 17 years I invested the maximum allowance every year, reinvesting all dividends and tax credits received – less the Pep managers’ charges, of course.

The ceiling on investment has changed several times. From 1987 to April 1991 I invested a total of £19,200, and from then to 1999 a further £72,000 – £6,000 a year in so-called general Peps and £3,000 a year in single company Peps. I kept investing the maximum allowed when Labour replaced Peps with individual saving accounts in 1999, and I have now invested £35,000 in Isas at £7,000 a year.

That makes a grand total of £126,200 invested since 1987, some of which I funded by selling shares in my main portfolio, which of course, is subject to both income tax and CGT.

Looking through my files, I find that I have generated no fewer than 463 contract notes, but the effort has been well worth it. When I had my Peps and Isas portfolio valued for this article earlier this month it was worth £1,015,843. In spite of the stock market crash in 2001, the average annual return is about 21 per cent.

My investing strategy has never varied. My first Pep investment, back in 1987, was in Pifco, the Manchester-based electrical appliance manufacturer. It was typical of the type of company to which my “DVY” approach – defensive value, plus yield – has always attracted me. It had valuable brands, a big proprietorial/family shareholding, and it was cash-positive with a history of profitability and rising dividends.

In addition, it was a small cap company and I judged it very likely to be on the receiving end of a takeover from a larger player one day. It was, very profitably for me, 14 years later.

As a small cap specialist I take a great deal of care over stock selection, researching the targets thoroughly, getting to know the managements wherever possible, and attending annual meetings whenever I can.

On many occasions I have been the only attending shareholder, which at least offers the chance of an uninterrupted dialogue with the board. On one occasion I was even offered a non-executive directorship, which I accepted.

Of course, not all my selections have been successful. I have had my misjudgements and disappointments. But where I have got it wrong I have usually acted speedily and decisively; the tax advantages of Peps and Isas are just too valuable to squander.

Thankfully, I have had many more successes than failures over the years, and I have benefited from a number of takeovers of companies in which I held a signature number of shares, including Bridport, Breedon and Trafford Park Estates as well as Pifco.

I have taken numerous tax-free profits by selling from my Peps and Isas shares that are performing well while retaining exposure to any further upside in my main portfolio. Most recently, I have done this with James Fisher and Lookers. Among my current favourites are Clarkson, Jarvis Hotels, P.Z. Cussons, Thorntons, Titon, Windsor and Wintrust.

I don’t know whether I am the first private investor to build up a portfolio worth £1m in Peps and Isas. Perhaps I am only the first newspaper columnist to do so. But I do feel that most investors have not taken the taxation advantages of these vehicles on board.

The wealthy seem to regard them as a rather pointless chore, perhaps because they think that the investment ceilings are too low to justify the efforts involved. The less well-heeled tend towards a rather inconsistent approach, investing in some years but not in others, and often holding on to poorly performing shares long after they should have been dumped.

Both these approaches are wrong. If funds allow, the key is to invest the maximum amount every year, reinvest all dividends and keep a close eye on your holdings to make sure your average returns are not depressed by a few poor stocks.

Investors need to remember that, in the eyes of the Inland Revenue, Peps and Isas are divorced from any other holdings you may have. This means it is possible, for example, to create a loss in your main portfolio, off-setting it against other taxable profits, and then buy back the same stock in your Peps and Isas portfolio, ensuring that the profit from any future recovery is tax-free.

Those who think that investing in this way has its tedious side are not entirely wrong. One of the worst irritations is that companies quoted on the Alternative Investment Market (Aim) cannot be held in Peps and Isas.

This means that when a company leaves the main market for Aim – usually to save costs or to benefit from lighter regulation – the shares have to be sold. Obviously, they can be repurchased for the investor’s main portfolio, but the tax advantages are lost. This is a manoeuvre I have carried out with several companies including Samuel Heath and Rowe Evans.

I have never worried too much about the costs of investing. In my view this pales into insignificance against the main issue, which is choosing the right stocks. I pay normal transaction costs plus a 0.5 per cent (plus value-added tax) manager’s charge on the capital value of most of the Pepsas. This is more than covered by my current overall dividend yield of 4.5 per cent – leaving about 4 per cent for dividend reinvestment.

Gordon Brown, the chancellor, confirmed in his pre-Budget report last week that Isas are set to become rather less tax efficient. The 10 per cent tax credit on dividends is to be withdrawn in April, and the annual investment allowance is to fall from £7,000 to £5,000 in April 2006.

I think this is a retrograde step. These measures will make only a small difference to Treasury revenue, and they are bound to discourage many people from using Isas, which seems illogical given that they are supposed to encourage saving.

But I think the benefits remain well worth having, particularly if you have already built up a sizeable nest egg. I intend to carry on very much as before, building my portfolios brick by brick, analysing, researching, visiting, always seeking to improve performance.

I’m currently interested in Jarvis Hotels and Thorntons, the chocolate maker, both of which are in play with management buy-outs mooted. I hope that both will generate profits and cash for reinvestment early next year.

Inevitably, the recovery in the market that lifted my Peps and Isas to the £1m level has brought yields down and made bargains much less easy to find. But 45 years of investing have taught me that there are always opportunities out there.

Not much changes, really. The two main ingredients of successful investing remain common sense and, above all, patience. My book about investing, if I ever get it finished, will be called Making a Million – Slowly.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2003) How I made £1m from £126,200, Financial Times, 20 December.

© The Financial Times Limited 2003. All Rights Reserved.

How can I do what he’s done?

Lucy Warwick-Ching

Can’t I just win £1m on the lottery and put it into an Isa?

Inland Revenue rules say you can put only £7,000 into a maxi stocks and shares Isa each year or £3,000 into a mini cash Isa. To become an Isa millionaire you would need to put the maximum amount in each year, play the markets and hope your shares perform well enough to give the value of your portfolio a strong and frequent boost.

If £7,000 a year is the top whack, how has John Lee managed it? He must have been investing for centuries.

He started investing in these tax-free products when they were launched in 1987 as personal equity plans (Peps). He invested the maximum all the way and carried on when Isas replaced Peps in 1999.

So he has paid in a total of £126,200 since Peps were launched.

So if I invest in Isas for the next 16 years, the same amount of time as he did, could I become an Isa millionaire?

Giles Pidcock, managing director of Baxter Fensham Financial Planning, says: “If you paid £7,000 every year into an equity Isa for the next 17 years, you would need a return of 21.09 per cent on your investments to make a million.”

If this sounds like a tall order, Pidcock suggests clubbing together with your partner because you’ll be able to double the amount you can invest to £14,000 a year. “If you do it together you would only need a return of 14.56 per cent to achieve the million,” says Pidcock.

That still seems an awful lot, especially in the present state of stock markets.

It’s even harder than that I’m afraid. From 2007 the most that can be invested in an Isa will be cut from £7,000 a year to £5,000. The amount that can be put into a cash Isa will be cut from £3,000 to just £1,000.

My portfolio will have to work hard, then. Is there anything that’s likely to outperform other stocks?

Meera Patel, senior analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown, says: “The biggest mistake people make is to buy high and sell low. Many people simply end up putting their money in the most fashionable funds promoted by investment firms. But as technology shareholders found out to their cost in the late 1990s, investing in funds that are the flavour of the month is a recipe for disaster. The way to make money is to be contrarian.”

She says UK and other European stock markets are still much lower than they were in 1999. “Now is a good time to put your money in.”

Pidcock says investors who want to become Isa millionaires will need to be aggressive. “You will need a lot of luck as well as taking on greater risk. Areas to invest in include smaller companies, sector-based and emerging markets funds.”

Does it make much difference how I invest? Could I, for example, find my money being eaten up by charges?

Pidcock says one of the biggest drags on investment returns is the annual management charge, which can range from 1 per cent to 5 per cent.

The best way to invest in several funds is through fund supermarkets, which have greatly reduced charges. Even if you are investing in only one fund, the initial charge is usually cut by 2 or 3 per cent if you invest via a supermarket, and in some cases may be removed.

Some independent financial advisers also offer their own supermarkets where you can buy funds, without advice, at discounted prices. They include Chelsea Financial Services, Bates Investment, Hargreaves Lansdown, Chase de Vere and Charcol.

How can I make my money work harder to achieve high returns?

Advisers suggest spreading your money across a range of markets and investing in funds with different styles. But how you go about it depends largely on your attitude to risk. “If your sole aim is to try to become an Isa millionaire, you should be more adventurous because the risk of investing in volatile areas such as emerging markets and smaller companies may pay off over the longer term,” says Patel.

It all sounds a bit more feasible, but are there any further problems.

There is an inheritance tax issue, I’m afraid. Pep and Isa money cannot be held within a trust. This means your £1m investment will be subject to IHT when you die. “Most assets can be placed in a trust, but not lsas or Tessas because they already attract tax relief,” says Pidcock. “For example, if you did not own a house, the first £255,000 of your Isa and pep portfolio would be free from tax, but the rest would be subject to 40 per cent tax if you are a higher rate taxpayer.”

Is there anything else?

Once the 10 per cent tax credit that equity Isas can currently claim on dividend income is abolished from April 2004, the case for saving within an equity Isa also becomes weaker.

![]()

Source: Warwick-Ching, L. (2003) How can I do what he’s done?, Financial Times, 21 December.

© The Financial Times Limited 2003. All Rights Reserved.