Valuations

What I look for

I have always believed that most investors and analysts overcomplicate matters. I try to focus on just two yardsticks when investing in a trading company, e.g. PZ Cussons: dividend yields and PERs, and two for an investment or property company, e.g. Daejan – net asset values (NAVs) and gearing, i.e. the level of borrowings a company has relative to assets. The gearing factor importantly also applies to trading companies.

Dividend yield

Company A has a share capital of £1,000 in shares of £1 each.

It pays a dividend of 10p on every share.

Thus, if an investor buys £100 worth of shares at £1 each they will receive a dividend of 100 × 10p = £10.

Therefore their return is £10 on an investment of £100, i.e. they have bought on a 10% yield.

However, if the share price has risen to £2:

The investor’s £100 will buy only 50 shares.

Thus their dividend will be only 10p × 50 = £5.

Therefore they have bought on a 5% yield (£5 on £100).

Price earnings ratios

PERs work on the same principle.

| Company B makes pre-tax profits of: | £1,000 |

| It pays corporation tax of 20%: | £200 |

| Therefore its after-tax profits are: | £800 |

If the company has a share capital (the total amount of money/investment subscribed for by investors, and thus available for use in the business) of, say, £8,000 divided into 8,000 shares of £1 each, which also have a market price of £1, then the price earnings ratio is the total market capitalisation, i.e. £8,000 (8,000 × £1).

Divided by the post-tax profits as above, £800:

Therefore it stands on a price earnings ratio of 10: £8,000 ÷ £800

However, if the share price rises from £1 to £2, then Company B has a market capitalisation of £16,000 (8,000 × £2).

Its after-tax profits are still £800.

Therefore it is on a price earnings ratio of 20: £16,000 ÷ £800

A single-figure PER indicates that, rightly or wrongly, a company is modestly rated – that there is a limited expectation or uncertainty about further profits growth. Initially, investing on a lowish PER – something I try to do – is ‘safer’ than buying into a share on a PER of, say, 20+. In the case of the latter, the high PER means that the expectation of profits growth is already built into the share price. Fine, if it does deliver, but if it fails to do so then its rating could ‘fall’. Thus if a PER rating on a particular PLC falls from 20 to 10, the shares will have halved – bad news!

Let us put dividends and price earnings ratios together in Example C, shown opposite.

Personally, I like to buy shares on a modest valuation – ideally, say, a dividend yield of 5–6% – and on a single-figure PER. Apart from the obvious attractions of receiving the dividend, the payment of a dividend acts as a significant discipline on the Board of a PLC in that it has to find the cash, each year, to pay those dividends.

Company C has capital of £10,000 divided into 10,000 shares of £1 each.

| It makes a pre-tax profit of: | £1,000 |

| Pays tax at 20%: | £200 |

| Therefore profit after tax: | £800 |

| It then pays out in dividends: | £200 |

| Retained profits: | £600 |

(We say the dividend is covered four times by available profits, i.e. £800 ÷ £200)

Company C is capitalised at £10,000.

Its PE ratio is therefore £10,000 ÷ £800 = 12.5

However, if its shares stood at £2, then it would be capitalised at £20,000 and its PE ratio would be £20,000 ÷ £800 = 25 (very expensive).

As far as dividend yield is concerned with the shares at £1:

Let’s say the investor owns all Company C’s shares, they would receive £200 of dividends on their £10,000 investment.

Their yield would be: ![]() (quite modest)

(quite modest)

Now what should you look for in the ideal investment? What we want is a company that increases profits (and hopefully dividends) each year and where the rating (PE ratio) that the stock market/investors place on the company’s shares increases significantly. This is the ‘double whammy’ any investor should be seeking.

Company D makes profits of £100,000.

It has a share capital of £800,000 in £1 shares.

Its shares stand in the market at £1 each.

| £100,000 | |

| Less corporation tax 20% | £20,000 |

| Post-tax | £80,000 |

| Stock market capitalisation | |

| 800,000 × £1 = | £800,000 |

| (i.e. it is on a PER of 10: £800,000 ÷ 80,000) |

| Now let us say profits double to: | £200,000 |

| Less 20% corporation tax: | £40,000 |

| £160,000 |

And the stock market, because Company D is doing so well and is expected to increase profits again next year, values it not on a PER of 10 but on a PER of 20, so it is capitalised at: 20 × £160,000 = £3.2 million

Therefore each £1 share is now trading at £4 (£3,200,000 ÷ 800,000)

So although profits have only doubled, the shares have quadrupled. A double whammy.

As an investor, that’s what you should be looking for: increased profits plus an upward re-rating.

Keeping a record

In April 2000 I wrote about Vimto, a soft drinks manufacturer (see below). This makes the point perfectly.

New fizz from the kings of Vimto

But John Lee discovers that the company has much more to offer these days

For most investors, Nichols Vimto is a rather dour north of England company battling against the might of Pepsi and Coca-Cola.

But it holds many memories for me: not only did I drink Vimto as a schoolboy, it was an early share in my late mother’s portfolio. More recently, my investment ledger records a near trebling of the share price between purchase in 1991 and sale in 1995.

A visit to Nichols Vimto’s spanking new headquarters, midway between Manchester and Liverpool, gives a very different perspective. John Nichols, executive chairman, and Gary Unsworth, the first non-family managing director, point out that Vimto itself accounts for little more than 25 per cent of turnover. In reality, the group is now a broadly-based beverage company; hence the proposed name change to Nichols plc.

The “new” Nichols produces hot drink systems for Little Chef, Burger King, and British Petroleum. Through its Cabana subsidiary, it is third in the market for supplying draught soft drinks to pubs and clubs. It has also just won its first NHS order: for 20 hot drink trolleys at the Middlesex Hospital.

The group’s three former drink manufacturing units have been brought together in a new facility producing Vimto, Sunkist orange and Indigo.

Its fast-growing foods/ingredients business supplies own-brand products for vending machines, and food sachets for the hotel and catering sectors.

The plan is to double food sales over five years. All this reorganisation and change has inevitably led to a plateau in profits, but it points to a very different future.

Nichols has always delivered a progressive dividend. At about 100p, the shares yield around 9 per cent and are bumping along the bottom on a price/earnings ratio of only 6.5. The dividend is twice covered by earnings. For me, it is an ideal stock for personal equity plans or individual savings accounts. I have been buying both before and after the recent results.

My hope is that more investors will recognise the metamorphosis that has transformed Nichols. In December, the group bought back nearly 5 per cent of its equity. It would, almost certainly, have bought more had it not been barred from doing so because of the 60-day close period around the results announcement.

This brings me to an interesting issue: just who is supposed to benefit from the closed period restriction on companies buying their own shares?

The share price invariably sags when the company itself is barred from the market, meaning that sellers get a less attractive price. Conversely, this is a window of opportunity for shrewd prospective buyers who are prepared to study close period dates carefully.

I fully accept the logic of restricting directors’ share trading – but why the company? Nichols is clearly frustrated by its lowly stock market value, and I sense a real desire by John Nichols and Gary Unsworth to raise its profile and deliver shareholder value. A new share incentive scheme will certainly focus the minds of key executives.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2000) New fizz from the kings of Vimto, Financial Times, 23 April.

© The Financial Times Limited 2000. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

Nichols has been one of my most successful investments in recent years. The key was the company’s decision to ‘outsource’ production, leaving management to focus on marketing and distribution. In addition, capital was no longer tied up in the manufacturing process. Profits growth and a re-rating have delivered the ‘double whammy’ which we seek and the shares have appreciated over ten-fold since I wrote this article.

I paid 100p per share on a yield of 9% and on a PER of 6.5 – very modest valuations. Nichols made a crucial decision a few years ago to outsource the production of Vimto and to focus its energies on marketing both in the UK and overseas, particularly in the Gulf States. Profits and dividends have since grown apace and the shares have been substantially re-rated. They are now around £12 each, with a dividend yield of 1.5% and a PER of 28. It has been an outstanding investment and currently is one of my largest holdings.

The article ‘Dicing with dividends’ overleaf records me being able to pick up Fenner – one of our most successful niche engineering companies in conveyor belting, etc. – after the 2008 financial crisis on a 9% yield at 65p and 70p. Profits growth and a re-rating took them up to nearly £5 before slipping back below £4. Unfortunately I sold half my holding too early at £1.85p, but still at treble those first purchases.

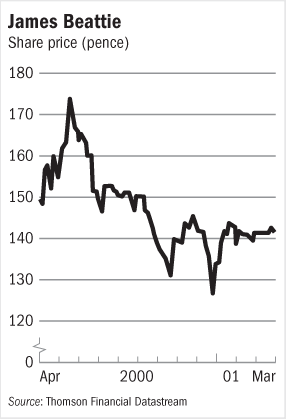

The following article ‘Plenty of potential in store’ records me buying into department store retailer James Beattie, on a ‘double eight’ – an 8% dividend yield and a PER of 8. Modest valuations, particularly as it had no gearing (borrowing). However, looking back at my investment records Beattie was not a great success. I paid just over 180p early in 1998, selling later that year at 140p and early in 1999 at 170½p – so an initial loss. Nevertheless, I bought again in 2003–4 at between 113p and 131p, taking a small profit later that year before finally being on the receiving end of a cash takeover in September 2005 at 168p. So not a great success – probably breakeven overall – but as most of the transactions were in my PEPs/ISA, at least I had some much appreciated tax-free dividends.

Note the importance of being patient: although the shares appreciated in those early years, it was 2009 before Nichols really started to motor

Source: Lipper, a Thomson Reuters company

Dicing with dividends

John Lee

When I first started to take an interest in the stock market 50 years ago, the big figure dividend yields were offered mainly by plantation companies – rubber and tea stocks pregnant with nationalisation and commodity risk, or the occasional rather speculative shipping line – sectors that have virtually ceased to exist.

Then I remember the secondary banking/stock market crash of the early 1970s when equities were totally friendless and any number of established plcs offered huge yields. Investors who bought in then did extremely well when markets recovered. Today, we are in an extraordinary period when not only do large caps yield 5–6 per cent and “proper” small caps twice that, but returns on cash deposits are minuscule.

It is thus hardly surprising that we are beginning to see some braver – I would say shrewder – souls edging back into individual savings accounts (Isas). In the last two months, more people were buying than selling Isas for the first time since April 2008. Net inflows in December were treble those of a year ago. Of cource, most investors are still clinging to cash – paralysed with uncertainty and shock at our financial meltdown. But, when recovery and optimism return, sentiment could change very quickly.

Currently, I am very focused on dividends – accepting that few shares are likely to show capital growth in the short term. From my higher-yielding stocks, I am hoping for maintenance of dividends – a dividend increase is a bonus; a “passing” or slashing of the payment is bad news. These board decisions reflect not only the profitablity/debt levels of the company, but also its attitude to shareholder dividends, so past dividend history is an important consideration – as is the size of directors’ holdings.

February saw me make two further purchases of Fenner, the conveyor belting/advanced polymer products company on a 9 per cent yield – tax-free within my Isa. Almost a year ago, the company “placed” shares at 223p with institutions to raise funds primarily for a US acquisition. I added to my holding at 65p and 70p – highlighting the ridiculous hammering of word-class businesses such as Fenner. What other class of asset – certainly not house prices or even commercial property – has fallen by anything like this percentage?

Writing in November’s annual report, the company’s financial director said: “The group is well placed, not withstanding the current disruption of financial markets, to fund and support its operations, with continuing access to medium and long-term debt finance, cash resources and, where necessary, shorter-term facilities.” The chairman concluded: “Despite the inevitable challenges, we believe we are very strongly placed to outperform. For the longer term, our business drivers remain highly positive.” Hardly the language of a likely dividend cut!

Elsewhere, very recent maintained dividends from BBA Aviation (final) and Town Centre (interim) produced modest share price appreciation, as did Bodycote and Vitec’s small dividend increases – all with encouraging trading statements. Current yields on all four are still between 7 and 13 per cent.

I couldn’t resist picking up more Town Centre at 60p – it was at 64p in 1999 that I first bought into it, selling some shares at 138p in 2002 and more at 595p in 2006. Property shares are hardly flavour of the month but the yield and a NAV of 270p are tempting.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2009) Dicing with dividends, Financial Times, 7 March.

© The Financial Times Limited 2009. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

Here I am drawing readers’ attention to the way stock market movements are often exaggerated both ways – sometimes too bullish, sometimes too bearish. I was convinced that the subprime banking/financial crisis had driven many quality shares down to absurdly low levels. I was delighted, for example, to buy conveyor belting manufacturer Fenner on a 9% yield. Subsequently they rose to nearly £5 before falling back somewhat as the world’s mining industry became less buoyant.

Plenty of potential in store

It’s in an unloved sector, but John Lee has lots of time for James Beattie

Retailers are out of favour with investors. So perhaps it is understandable that those of us outside the Midlands value the James Beattie department store group on a “double eight” – dividend yield of 8 per cent and price/earnings ratio of eight.

But surely the thousands of customers who shop at Beatties each week must appreciate that the shares are worth more? I recently visited the Solihull store to meet managing director Chris Jones, who has been with the group for 35 years, and finance director Bill Kelly, and was impressed.

I invested in Beatties in 1998, attracted by the yield and cash pile on the balance sheet. As the share price drifted, I became bored and took a loss. After my recent visit I repurchased (at virtually my selling price), but this time I knew far more about the company.

Beatties, founded in 1877, has nine stores, and is described by market reseach company Verdict as “a strong, impressively profitable and enduring player”. It sells branded goods to middle-class customers, with a big emphasis on ladies’ clothes, fashion accessories, perfumery, and household and leisure goods.

The group has delivered shareholder value, albeit unrecognised in the share price. Since 1996, on the back of operating margins rising from 5.7 per cent to 8.8 per cent, earnings per share have nearly doubled. Dividends have risen 70 per cent. Beatties has always maintained a high payout ratio and is content with a one-and-a-half times dividend cover.

While profits to January, which should be announced early next month, are forecast to plateau, the scale of the group’s expansion has yet to be reflected in the shares’ rating. The group has set about increasing its selling space by 50 per cent. This is forecast to cost £28m (half the current market capitalisation) and is being financed almost entirely from internal resources. New stores will open in Birmingham this year, in Huddersfield in 2002 and, it is hoped, in Gloucester the following year.

The five-floor Birmingham store in Corporation Street, formerly C&A, is regarded as a coup, and should be profitable from year one.

In many ways Beatties is a textbook exercise: a settled and ambitious management, an emphasis on staff training, low employee turnover, coupled with a ruthless “clean stock” policy and a “customer is always right” attitude.

As an investment it offers yield, nil gearing, full asset backing and every opportunity for a re-rating as profits advance over the next two to three years.

For income seekers there is an 8 per cent yield and scope for steady capital appreciation, spiced with a predatory potential if the shares don’t buck up soon.

I also like the board’s willingness to build up directors’ shareholdings through market purchases, and not just by relying on share options, although these are in place as well.

If I have one criticism, it is that Beatties appears to have put little effort into shareholder relationships. Attendance at the annual meeting is thin, and there are no shareholder discounts or benefits.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2000) Plenty of potential in store, Financial Times, 24 March.

© The Financial Times Limited 2000. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

My investment in Midlands’ department store James Beattie was not a particular success – I probably broke even overall. Its new Birmingham store, once C&A, was not a winner, beset with all sorts of traffic problems. However, the fundamental point here is that because I had bought it at a low level – a dividend yield and a PER both of 8 – there was little downside risk. The key to building an appreciating portfolio is to avoid the losses – don’t take unnecessary risks or buy at inflated levels.

Family PLCs

The following article ‘Family values at a discount’ centres on family-controlled property group Daejan. When I started investing years ago there were quite a number of residential property companies to invest in, but most have been taken over. Daejan represents one of the few opportunities to invest in London residential property today, although it also owns significant commercial property and both residential and commercial property in the USA. With overall gearing of less than 20%, Daejan is an excellent example of a low-risk property investment. In recent years its NAV (assets less liabilities) has been north of £50 per share. My buying has always been at a good discount: between £41.50 in 2007 and £27.10 in 2011. The current price is £40.

Family values at a discount

John Lee

Proprietorial PLCs – companies that are controlled or dominated by one family – have always fascinated me. I hold shares. I like the alignment of board and shareholder interests, the focus on conservative growth and “stewarding” a business through generations, their generally low borrowings and usually progressive dividend policy.

Each has its own characteristics and ethos – and this interests me from a wider sociological perspective. Property company Daejan is a classic example, as I observed when attending its annual general meeting (AGM) last month.

I have held Daejan shares in my individual savings account (Isa) for some time – paying between £29 and £40 in 2007, and then about £27 in 2008 and 2011. In all cases, I was buying at a discount to Daejan’s net assets. Today, the share price is £24, capitalising the company at £390m, and the dividend yield is 3 per cent.

Daejan is effectively 80 per cent owned by the Freshwater family, who injected their property interests into a cash “shell” in 1959. Over the years, shareholder returns have been very impressive: since 1981, the share price has appreciated 1,350 per cent and the dividend by 1,950 per cent, having increased annually for the past 30 years. Over a comparable period, the retail prices index has risen by 315 per cent.

About 50 shareholders and advisers attended the AGM, the majority somewhat elderly, for whom the gathering was clearly something of an annual ritual. This audience faced a five-man board – four Freshwaters and one non-executive who dates from 1971 and is thus not regarded as “independent”. Daejan’s founder, Osias – the father of the present chairman – escaped the Holocaust by leaving Gdansk, Poland, in 1939 on the last vessel out, and arrived in this country virtually penniless. The family commitment to Orthodox Jewry remains very strong and Jewish educational charities have benefited handsomely over the years from the company’s generosity.

In the 1960s, the group was the largest private landlord in the UK and, over the years, diversification into commercial property and the US has taken place. At March 31 2011, 80 per cent of the company’s £1.25bn-worth of property was in the UK, split between commercial and residential. Daejan is probably the largest residential owner in London.

Overall gearing is low, with borrowings less than 20 per cent. Within the portfolio, the £40m redevelopment of Africa House in Holborn – likely to deliver a £7m annual rent roll – has significant potential.

On the other hand, the portfolio includes nine care homes, leased to Southern Cross, though these are only 2.5 per cent of the total portfolio.

Daejan’s annual report discloses a net asset value per share of £51.43p, up from 2010’s £48.17p – but even this may be understated.

So, at the current share price, an investor is getting £1 of property for less than 50p. I cannot think of any comparable example.

Daejan is hardly in the vanguard of progressive corporate governance. But the huge discount, participation in London residential values and a hopefully rising 3 per cent dividend yield are compelling. I can also recommend the excellent AGM kosher buffet – many delicacies were reminiscent of my late grandmother’s traditional cuisine!

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2011) Family values at a discount, Financial Times, 2 October.

© The Financial Times Limited 2011. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

When I wrote this article, property company Daejan’s share price was £24 but its net asset value was over £50 – thus it was a ‘no-brainer’. Given the company’s modest gearing, its shares just had to recover unless we faced a meltdown of Armageddon proportions. I am glad to say that by mid-2013 Daejan’s shares had recovered to around £40.

Thus we have two different types of ‘value’ purchases – Nichols/Fenner/Beattie on attractive dividend yields and modest PERs, and Daejan at a significant discount to assets.

Value

I must also refer to a third category where the ‘worth’ of the business is in real terms surely more than the stock market capitalisation. Two examples, Christie, in business services and stocktaking, and Quarto, in book publishing, are in my current portfolio.

Share prices can belie true value

John Lee

My investment approach is based on a belief that “value” always comes through in the end – although I quip that, with some companies, many shareholders will have died waiting! Sometimes it can feel as if I am creating a portfolio for my future grandchildren.

Usually, my investment judgment is based upon relative dividend yields, price/earnings (p/e) ratios, price/earnings growth (PEG) ratios, market expectations, etc. But with property companies, a value assessment is more easily made with professionally certified net asset values – hence my earlier purchases of Daejan and Town Centre at big discounts.

Often, however, there is a clear differential between stock market capitalisation and what a trade buyer or competitor might pay – thus some surprisingly high premiums are seen on takeover bids. I have always felt, for example, that family-controlled flavours/fragrances manufacturer Treatt – my largest holding – is “worth” significantly more than its market capitalisation, although it is determinedly independent.

Occasionally, a glaring anomaly arises particularly with a small PLC that falls below most investors’ and analysts’ radar: I believe Aim-quoted Christie Group to be a classic example.

I have been “aboard” for 10 years, buying first in the mid-30ps in 2002 and seeing them climb to a peak of 272p when pre-tax profits in double figures were reached.

An expensive software venture then acted as a considerable drag, thankfully now terminated, and trading conditions in recent years have not been easy with dividends passed in 2009/2010.

However, Christie has steadily developed over the years and is highly regarded within its two principal sectors: professional business services, covering valuing, buying, selling, financing a wide variety of businesses in the leisure, care, retail sectors; and stocktaking and inventory systems and services.

Christie’s business services are provided from 14 offices in the UK and 13 abroad – having opened in Dubai last year and Dublin very recently – and helped it win Estates Gazette’s “Most Active UK Agent” award in the Leisure and Hotels category for a second year. Apart from disclosed clients such as Von Essen Hotels and Southern Cross, it does a substantial amount of work for banks, insurance companies etc, with no publicity. Most of its major competitors are now virtually all overseas-owned.

Christie’s stocktaking business – number one in the UK, number three in the world, with 11 offices and more than 1,000 employees – has roots going back to 1846. But new clients include Zara, Butlins, Tesco Pharmacy.

Total group revenue increased to £53m for 2011, split broadly equally between the two divisions. With directors and staff owning 65 per cent, marginal profitability and a recent dividend reduction, the shares have come back to 52p, giving a paltry £13m capitalisation. So I recently added more at 49p to my already sizeable holding. This year has reportedly started well and I expect the high operational gearing to build bottom line profitability.

I would suggest a trade buyer might value Christie at £1 for every pound of turnover – £50m-plus – or four times its present market valuation. But even a more conservative calculation makes a mockery of the present share price. Indeed, the group floated at 145p in 1988, when it was considerably smaller.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2012) Share prices can belie true value, Financial Times, 5 May.

© The Financial Times Limited 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

My core investment philosophy is that ‘value’, i.e. real worth, always comes through in the end, but you must be patient. Here I focus on leisure industry services/stocktaker Christie Group – its share price graph (see figure overleaf) demonstrates wild gyrations over the years. My belief is that any price below £1 represents a bargain; it was ‘floated’ at 145p in 1988 when the business was much smaller than it is today.

They touched nearly 275p in 2006 – now less than one-third of that. Hopefully, in time …

Source: Lipper, a Thomson Reuters company

Misunderstood and undervalued

John Lee

The most frequent complaint from small-cap chief executives is that their companies are misunderstood and their shares are undervalued. Occasionally, this frustration spills over – as in the case of Laurence Orbach, founder and driving force of Quarto, the international book publisher.

In his chairman’s letter accompanying the recent 2010 results, he writes: “I know that it is considered inappropriate for executives and directors of publicly traded companies to stick their necks out and proclaim that their businesses are not understood by investors and should be more highly rated.

“I risk opprobrium for voicing my dismay that Quarto shareholders have not been better served by my explanations of the company’s virtues to the investing community. We have grown our business over the years, but could do much more if we were trading on a higher multiple of earnings.”

I concur, and happily declare my own interest as a long-standing shareholder.

Over the years, I have made 20 purchases – mainly for my personal equity plan (Pep) and individual savings account (Isa) – at prices between 211p and 88p.

Quarto is one of the largest international co-edition book publishers with two main strands of activity: its publishing segment publishes books, under imprints owned by the group; and its co-edition publishing segment creates books that are licensed to third-party publishers for publication under their own imprints.

Overall, 85 per cent of its total revenues derive from outside the UK. It is focused and risk averse, with a business model honed conservatively over the last 35 years.

Essentially, it publishes books of an enduring interest: “not looking for the next big thing, but the next lasting thing”.

Quarto’s top five sellers in 2010 give a flavour: Complete Guide to Writing, 1001 Movies you must see before you die, Anatomica Revised, 1001 Songs you must listen to before you die and Art: The Whole Story. None of these exceeds 1 per cent of group revenues – most sales are made through large arts and craft store chains and home improvement retailers.

Recent results showed encouraging profits growth, debt reduction and a welcome 5 per cent dividend increase – with current trading described as “interesting and exciting”.

But Quarto’s real value is in its niche business model and its £30m backlist of titles from which it derives substantial royalties – its books are sold in 35 countries and 25 languages. At 155p, a price/earnings (p/e) of 6 surely seriously undervalues this £31m capitalised business – offering a 5 per cent dividend yield covered 3.5 times.

Elsewhere, markets have inevitably been unsettled by the Arabic uprisings and consequent rise in the price of oil, but thankfully the majority of announcements emanating from my holdings have been positive.

There have been dividend increases from THB, Town Centre, and Wynnstay, and encouraging statements and newsflow from Capital Pubs, the Cable & Wireless duo, Christie Group, Dairy Crest, Gooch and Housego, MS International, Norcros, Park Group, Primary Health, S+U and United Drug, with “old friend” Dawson Holdings seemingly engaged in takeover talks.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2011) Misunderstood and undervalued, Financial Times, 5 March.

© The Financial Times Limited 2011. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

‘Misunderstood and undervalued’ is how I describe book publisher Quarto, a holding which I believe will ‘deliver’ in the future. The founder and then CEO Laurence Orbach vents his frustration in the annual report: ‘I risk opprobrium for voicing my dismay that Quarto shareholders have not been better served by my explanation of the company’s virtues to the investing community.’ Sadly, this brave and honest statement failed to bring about any improvement in Quarto share price and Laurence was deposed by shareholders’ vote in 2012. We hope that the new top team will succeed where Laurence unfortunately failed. Public company life can be cruel.

I have held both for many years, confident that in time ‘value’ will be reflected in either an upward re-rating or a takeover. ‘Value’ always comes through in the end, but sadly some shareholders may die waiting.

After 50 years of investing it is hardly surprising that I know what characteristics I look for in PLCs that I consider investing in, and the types of shares that I feel comfortable holding long term. Smaller caps, established, profitable, conservative dividend-paying companies, cash positive, or with low levels of debts are for me, preferably having a recognised ‘brand’ or unique selling point (USP) and preferably also trading internationally. The FTSE Small Cap Index contains smaller companies outside the FTSE 100 and the FTSE 250 indices. These companies make up about 2% of the UK market.

Generally speaking, small caps tend to be less well covered by analysts and thus offer greater opportunities to be ‘discovered’ by private investors. For me, no small cap can be too small – indeed, approximately 25% of my current portfolio is made up of companies with a market capitalisation of less than £50 million and others were below that figure when I first bought into them. Frequently these are what I term ‘family’ or ‘proprietorial’ companies, with control passing through the generations where the emphasis is on ‘stewardship’, one of my favourite investment words. By this I mean that we usually have family Board members, conscious of the efforts of earlier generations who created and developed the business, and conscious also of their responsibility to add worth and value during their tenure in a conservative way. So, ideally, organic growth with perhaps an acquisition from time to time, but no excessive risk taking or ‘betting the shop’ on a large, over-reaching deal.

In addition, those in an executive role often find that there are widows, maiden aunts, siblings or other relatives with significant shareholdings, who are totally reliant on the dividends from the ‘family’ PLC for their lifestyle. There used to be the saying ‘clogs to clogs in three generations’ – particularly applicable to many old mill-owning families – but as a generalisation those days are thankfully long gone. The current generation of family PLCs has hopefully recognised that to pass the reins to a member of the family who is just not up to it is a recipe for disaster.

These days one usually finds that a successful Board has a judicious mix of family and ‘outsiders’, promoted or brought in for their professional abilities rather than the size of their shareholdings. Over the years I have profited greatly from investing alongside families, albeit with far more modest holdings. It was in the 1970s that I started to focus on such companies by buying into the three Ps – Pifco, Pochin’s and Paterson Zochonis (now PZ Cussons) – all based in my North West homeland.

Unloved, unwanted and undervalued

Even so, John Lee believes that Pifco has a bright future in the electrical appliances market

For all the interest the stock market takes, Pifco, which makes small electrical appliances, might as well have stayed private under its original name: the Provincial Incandescent Fittings Company.

In spite of having a progressive record and owning valuable consumer brands (including Russell Hobbs, Carmen, Tower, Mountain Breeze and Salton), the company has been ignored by investors. In part, this comes from its profile which stems, I believe, from Michael Webber, chairman and chief executive. He is a very private person as well as a diligent manager.

While having a laudable and comprehensive mission statement, I am not convinced that Pifco has really tried to embrace shareholders. The AGM is held off-site and, although I have been a shareholder since 1977 and have had regular discussions, it was only very recently that I was allowed to cross the drawbridge and enter Fort Pifco – a large, red-brick, former textile mill in the Failsworth district of Manchester.

Pifco is one of several “proprietorial” plcs (my term) where a family either has the controlling shareholding or operates under some similar arrangement. (To its credit, Pifco enfranchised its “A” non-voting shares in 1998).

Succeeding generations regard themselves as stewards, conscious not only of responsibilities to employees, customers and shareholders but also to safeguard the family silver. With luck, they will provide growing dividends income and capital worth for members of the family not active in the business and, often, for charitable trusts and settlements.

Such companies usually are characterised by low borrowings, steady organic growth, modest bolt-on acquisitions and conservative image.

Pifco has much to commend it. It is a tightly managed and cash generative company with new products coming on stream continually. It also has some flexibility of manufacture, either at Wolverhampton or in east Asia, and racked up a very creditable achievement in turning round the loss-making Russell Hobbs in short order. Moreover, it has wasted no time in integrating Hi Tech Industries, a maker of lighting products, which it acquired recently.

How successful it will be in bringing home a bigger acquisition is uncertain. In my view, Pifco needs either to get bigger or be absorbed by a larger international group. It is known to have been circling Kenwood for some time.

Interim results just announced show further progress: pre-tax profits up 12 per cent and the dividend (I criticised the company in an earlier article for being too parsimonious) up 10 per cent and covered three times. Analysts project £4.2m pre-tax profits for the full year to April 30. With the share price around 135p, this implies a miserly price-earnings ratio of seven on a low tax charge.

I found Webber and James Wallace, a key colleague who also has a sizeable shareholding, welcoming and frank. But both had a bad dose of the “triple U” virus – unloved, unwanted and undervalued – that strikes so many smaller company directors today.

Pifco is clearly worth much more than its £24m capitalisation. I would be fascinated to hear just what value a brand consultant would place on it. There is also a large cash pile likely to be around £12m by year-end.

I left with two things. First, I now own a state-of-the-art Russell Hobbs kettle (which will be recorded in the register of shareholders’ interests).

Second, I have a clear belief that the Webber/Wallace duo is determined to deliver shareholder value. I would be surprised and disappointed if, in two years, my Pifco holding had not appreciated enough for me to re-equip my whole kitchen.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2000) Unloved, unwanted and undervalued, Financial Times, 25 March.

© The Financial Times Limited 2000. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

There is a saying that ‘small cap’ stocks are valued correctly only twice – on original flotation when they first went public, and when they are ultimately taken over. This article refers to electrical appliance manufacturer Pifco, which was my first PEPs purchase. It became one of my favourite holdings – tightly run, cash rich, with valuable brands like Russell Hobbs. Finally it was taken over, very profitably for me, by Salton of the USA in 2001.

Pifco (‘Unloved, unwanted and undervalued’) was a manufacturer of small electrical appliances – hairdryers, kettles – acquiring Russell Hobbs as it grew. They ran a very tight ship, operating from an old converted mill and always maintaining a large cash pile. Pifco was my first ever PEPs holding. Like PZC, it then had Ordinary and ‘A’ non-voting shares – as both companies were family controlled, whether I held voting or non-voting shares was somewhat academic, though obviously the ‘A’ shares were cheaper. Ultimately, with no family succession, Pifco was taken over by Salton in 2001, delivering me a significant profit.

Construction services/property developer Pochin’s was originally a great success story. I was impressed with its reputation as a ‘quality’ builder of schools, offices, warehouses, etc., with its own property developments becoming increasingly important and profitable. My £15,000 investment grew steadily until it was worth over £1 million by 2007. Fortunately, concerned that the share price of nearly £4 was too ‘toppy’, I sold some of my shares between 367p and 399p – quadrupling my original investment. Then, sadly, near-disaster struck: over-stretched in property development joint ventures, with sizeable borrowings and expensive guarantees, the 2007–8 banking/property crash nearly capsized the company. Thankfully, it survived, but as a shadow of its former self, with the shares currently limping along around 30p or at ![]() of their former peak.

of their former peak.

Nothing is certain in stock market investing – equity investment always involves a degree of risk.

Sparring over dividends

Just a great success story, but here again patience was required before the upward re-rating took place between 2009 and 2011

Source: Lipper, a Thomson Reuters company

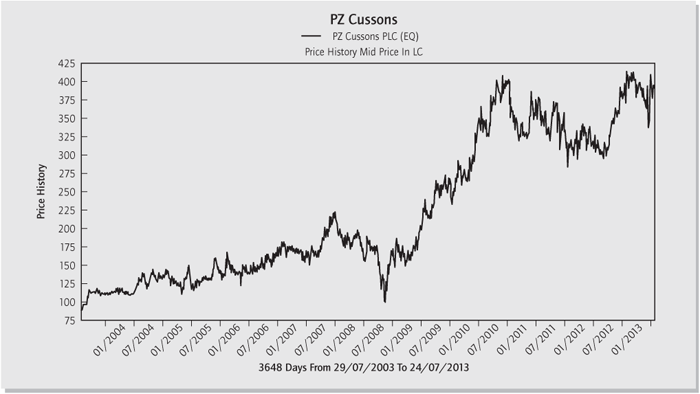

PZ Cussons was originally founded by Paterson, a Scot, and Zochonis, a Greek, in the 19th century to export textiles and basic commodities from the UK to Nigeria. Now controlled by the wider Zochonis family, PZC has become a major international manufacturer of soaps, detergents, cosmetics, etc., with substantial operations, particularly in Indonesia, Nigeria and the UK (I declared an interest having been an employee and non-executive director earlier). When PZC went public in the 1950s it was capitalised at just over £1 million; today’s capitalisation of £1.7 billion represents spectacular long-term growth, with shareholders not having to put in any further capital. I have been a happy holder for 36 years – today it is one of my largest holdings, with an annual dividend return of approximately 38% on original cost. This is what long-term investment is all about.

Shareholder stamina for a long haul

John Lee

At a time of considerable short-term uncertainty, it is perhaps apposite to remember what serious long-term equity investment is about, and the rich rewards if one chooses well and stays aboard. In 1953, West African merchants Paterson Zochonis went public with a stock market capitalisation of £1.2m. Its £10m annual turnover was thus described by the Evening Standard: “It bought palm oil, cocoa and ground nuts from the natives and sold them everything from combs to motorcars in return”. Hardly the politically correct prospectus language of today.

Over the next half century, through many economic cycles and civil war in Nigeria, it has grown into a international manufacturer of brand-based products predominately in the soaps, toiletries, cosmetics and detergents sectors in Europe, Asia and Africa – Nigeria always having been a very important market. Today PZ Cussons, as it is now known, has a turnover approaching £600m, 10,000 employees, with recent interim results indicating likely annual pre-tax profits in the £75m region.

Shareholders have done handsomely with regular annual dividend increases and no financial calls ever having been made on them. The group is now capitalised at £800m – in spite of slipping from its recent peak. So, anyone who modestly invested in 1953 would be very wealthy today. Sadly, I was only 11 at that time and had not quite started my investing career.

I first invested in PZC in 1976 – it now constitutes one of my largest core holdings. This family-controlled plc has to be one of Manchester’s greatest commercial success stories and the city and the North West have benefited greatly from the family’s beneficence as 11.5 per cent of the equity is in a charitable trust generating substantial dividend income. An indirect way of investing in PZC is through the £50m capitalised Manchester and London Investment Trust which owns approaching 5m shares, equivalent to 17 per cent of the trust’s current worth. This niche trust has been built up successfully by former Manchester stockbroker, Brian Sheppard, and offers one of the UK’s most valuable, but largely unknown, shareholder perks. It owns two Wimbledon debentures carrying the annual entitlement to 23 pairs of tickets for the Centre and No.1 Courts during Wimbledon fortnight. To qualify, shareholders must own a minimum of 2,500 shares (approximately £9,000 at current value). A weighted draw is held at the November annual meeting – the Sheppard family and company officers being barred!

For good order, I must place on record that in the past I have been a non-executive director of both PZ Cussons and Manchester and London Investment Trust but claim no credit for both those companies’ considerable achievements.

Choosing from the cornucopia of value available in the small cap sector is not easy, but I finally selected shower and tile specialist Norcros as a new purchase last month. Originally having been taken private in 1999, it returned to the stock market – at 78p last year and rose to a peak of 86p. Since then it has been downwards all the way, culminating in nearly 20 per cent of the price being lopped off when it recently announced that profits would be marginally below forecasts. I bought at 42p on a prospective yield next year approaching double figures, following significant directors’ buying. Norcros’s domestic shower division, brand leader Triton, must itself be worth the entire current group £60m capitalisation leaving its substantial tile interests both here and in South Africa in for free.

Finally, as evidence of the gap between current share prices and reality, just look at builders’ merchants, Gibbs and Dandy. In mid-January I bought at 275p. Today, after a takeover approach, they are 390p. I am hoping for a recommended deal well north of £4 – value always comes through in the end.

![]()

Source: Lee, J. (2008) Shareholder stamina for a long haul, Financial Times, 1 March.

© The Financial Times Limited 2008. All Rights Reserved.

Author note

This 2008 article focuses on PZ Cussons, arguably one of the North West’s greatest success stories and one of my major holdings. For years it was misunderstood and largely ignored by investors. In recent years, however, it has achieved the ‘double whammy’ of profits growth and substantially improved re-rating. Its market capitalisation (share price × number of shares in issue) in 2013 is over twice what it was in 2008.

Greater Manchester can also boast two other golden family stories: international floor coverings manufacturer James Halstead, which has had an outstanding record of year-on-year profits and dividend growth (both my daughters are appreciative shareholders), and in more recent years the aforementioned soft drinks manufacturer Nichols.

I first invested in Nichols in 1991 but only started to build up a worthwhile holding in 2000. What we have seen with Halstead, Nichols and PZC is not only real profits growth but also a significant ‘re-rating’ – moving on to a much higher PE ratio – thus delivering the ‘double whammy’ which is so beneficial to investors, as I discussed earlier.

Other ‘happy family’ successes for me include London-based electrical accessories manufacturer (plugs, sockets, light fittings, etc.) GET, taken over by Schneider of France, and three current holdings: short-term Birmingham lender S&U, controlled by the Coombs family; Redditch industrial lighting manufacturer F. W. Thorpe, controlled by the eponymous Thorpe family; and Leeds property investor Town Centre Securities, controlled by the Ziff family. Of course, some family PLCs have been much less successful, but overall this sector has proved a rich seam for me.

Some commentators regard family control as a negative, as they do large dominating directors’ shareholdings. I take the opposite view. I want those running my PLC investments to have large holdings – the larger the better – then I know that our interests are truly aligned.