CHAPTER 15: A TALE OF THREE CITIES: THE BOMBING OF MADRID (2004), LONDON (2005) AND GLASGOW (2007) – NEIL SWINYARD-JORDAN, TONY DUNCAN AND ROBERT CLARK

This case study examines and compares three terrorist attacks on European transport targets – the Madrid Railway Network (2004), the London Underground and bus network (2005), and Glasgow Airport (2007). It considers the comparative effects of the attacks, the respective reactions and the resultant economic impacts.

Terrorism overview

Terrorism is just one of the many threats that organisations need to consider as a part of their risk assessment process. As of 2011, over 6,000 armed and militant groups had been identified world-wide, an increase of 200% on 1988, which supports the argument that the threat is growing. The START Program has recorded around 100,000 global terrorist incidents since 1970. This equates to an average of approximately seven daily incidents.

Although acknowledging the existence of numerous terrorist organisations operating around the globe, it is not the intent of this case study to explore and understand their raison d’être, how they are financed or their individual objectives. Nor does the study make any attempt to distinguish between groups labelled as terrorists, guerrillas or freedom fighters.

‘One of the depressing lessons from the history of terrorism is that it is always likely to be with us.’ (English, 2009, p. 120).

Terrorism has been around for hundreds of years. Examples include the infamous Gunpowder plot of 1605, when Guy Fawkes and his cohorts attempted to kill King James I and his Parliament. The United Kingdom has been fighting Irish terrorism since the 1860s. Despite the apparent success of the Northern Ireland peace process, and the subsequent power-sharing arrangement between the various factions in the Northern Ireland Assembly, there is still a serious terrorist threat from dissident Irish Republicans. Meanwhile, the Spanish have been in conflict with the terrorist organization Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) for four decades.

Enter the suicide bomber

Personal self-sacrifice has become a way of operating for some terrorist groups. This was developed into a weapon of war during World War II with the advent of the Kamikaze. It was in Lebanon in 1983 that the first terrorist suicide bombing occurred, when terrorists targeted the US Embassy. As of 2005, over 350 suicide attacks had been executed in more than 20 countries. Suicide bombing is a powerful psychological weapon, surpassed in the ‘fear factor’ it generates only by weapons of mass destruction.

Terrorism and building design

‘In a bomb blast, a square metre of glass can produce up to 1,800 razor sharp fragments. These flying glass shards cause more damage, injury and death than the explosion itself.’ – (Advanced Glass Technology, 2014).

Modern architecture has for many years made extensive use of glass in building designs. One only has to observe the skyline of any modern city to note that, from a distance, many buildings appear to be made entirely of glass. Indeed, many railway stations that date back to Victorian times incorporate glass canopies in their design. This is a dream situation for terrorists as flying glass has the potential to greatly improve the effectiveness of their bombs.

Terrorist goals

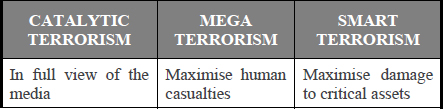

While each terrorist group will have overarching objectives of a political, religious or nationalist nature, each individual terrorist strike will usually look to achieve three goals. Savitch defines these as ‘Catalytic Terrorism, Mega Terrorism and Smart Terrorism’ (Savitch, 2008, p. 38) as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12: The Savitch ‘three goal’ model

The 9/11 attacks achieved all three of these goals, whereas the subsequent attacks on the London Transport (7/7) and Madrid railway system (3/11) only achieved a Mega and Catalytic Terrorism effect. The Glasgow Airport bombing only achieved the Catalytic goal and while the Madrid bombing did not achieve a ‘Smart’ effect, it did succeed in bringing down the Spanish Government.

History shows that the three goal Model does not always apply. Evaluation of the IRA’s 1990s UK Mainland bombing campaign demonstrates that the targets were primarily economic. The campaign did not aim to achieve a Mega Terrorism goal as prior warnings minimised human casualties. With an estimated 75,000 people evacuated from the city centre prior to the explosion, the casualties from the 1996 Manchester bombing could have been horrific without prior warning.

Terrorist threat to transport

The worst terrorist atrocity to date which also involved an act of self-sacrifice by the perpetrators was the calculated and sophisticated terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre in 2001. By flying hijacked aircraft into the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon, not only did they cause the deaths of almost 3,000 people, but close to another 600,000 also lost their jobs.

Major cities are often targeted and London is no stranger to terrorism. Local organisations take the threat very seriously. A London Chamber of Commerce survey revealed that its members rated terrorism seventh out of 17 threats in terms of being a risk to their finances. 44% of the respondents listed terrorism as a concern.

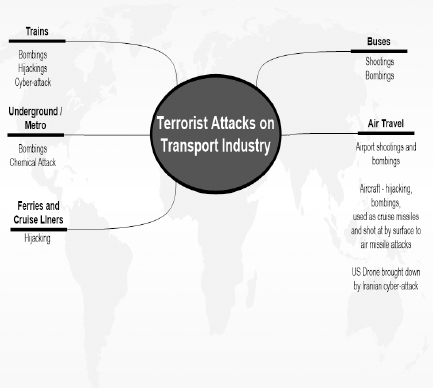

Traditional, or classic, terrorist weapons such as the bomb and the bullet have been available to terrorists for centuries. There is no reason to suggest that this approach to terrorism is likely to recede as these weapons are comparatively easy to obtain. The arrival of the suicide bomber has given terrorists a new, efficient and frightening means of delivering their attacks. In the case of the transport industry, with two recorded exceptions all types of attack have been traditional (see illustration below) and examples of suicide bombings abound.

While the Achille Lauro cruise liner hijacking (1985) and the Netherlands train hijackings (1970s) are exceptions, there have been examples of multiple terrorist attacks against the transport targets over the last 20 years as shown in Figure 13, below.

Figure 13: Examples of terrorist attacks conducted against transport and tourism targets

The preceding illustration provides an overview of the type of terrorist attacks that have targeted the transport sector. This overview is by no means definitive and excludes areas such as air and maritime cargo, road haulage and private air travel.

Whilst the annual Glasgow Airport annual passenger count is around eight million, London Underground carries in excess of one billion travellers annually utilising over 200 stations. The Spanish rail network has many hundreds of stations and transports in excess of 500 million passengers per annum. Apart from a plethora of security cameras, both forms of rail transport along with buses are considered to be ‘open’ to terrorist attack while UK airports are considered as ‘secure’, despite the fact that between 1970 and 2010, global terrorist incidents targeting airlines and airports numbered 1,044. This excludes thwarted attacks.

Madrid Train Bombings, 2004

On 11 March 2004, an example of mass-casualty terrorism occurred in Spain. Terrorists prepared 13 bombs inside plastic bags and backpacks, and placed the devices in twelve passenger carriages, spread across four different trains. They expected the bombs to detonate when the trains would be packed with rush hour commuters. Ten of the bombs exploded, killing 191 and injuring 1,841.

Within days of the bombings CNN reported knowledge of an alleged Al-Qaeda document claiming responsibility for the attacks. One of the statements made was: ‘We think the Spanish government will not stand more than two blows, or three at the most, before it will be forced to withdraw [from Iraq] because of public pressure on it. If its forces remain after these blows, the victory of the Socialist Party will be almost guaranteed – and the withdrawal of Spanish forces will be on its campaign manifesto.’ This is exactly what happened. Al-Qaeda was seeking regime change in Spain in an effort to ‘separate Spain from its allies by carrying out terror attacks.’

Examination of this these attacks identifies a number of issues relating to business continuity management, security and emergency planning. The impact of the bombings on businesses was immense in addition to the unexpected change of government, with hospitality and tourism bearing the brunt of the impact.

‘For the first forty eight hours or so after the bomb blasts there was an intense debate around the authorship of the attack. . . Figures in the governing party, the Pardito Popular, made it clear from the outset that they believed the Basque separatist movement, Euskadi ta Askatasuna (‘Basque Fatherland and Liberty’) or ETA was responsible.’ – (Garvey & Mullins, 2009).

Within days of the Madrid train bombings, eight million Spaniards had taken to the streets to march against terrorism. Controversy regarding the handling and representation of the bombings by the government arose with Spain’s two main political parties, the Partido Socialista Obrero Español and the Partido Popular, accusing each other of concealing or distorting evidence for electoral reasons.

The timing of the bombings was also significant as they occurred three days before general elections and this had a direct influence on the defeat of the incumbent José María Aznar’s Partido Popular, which had obtained a small but narrowing lead in the opinion polls. The party was anticipated as highly likely to win the general election but was voted out of office following the attacks.

The victorious Partido Socialista Obrero Español advocated a withdrawal of Spanish troops from Iraq, regarding this as a strong vote winner, because it would appease the terrorists and hence minimise the risk of future attacks in the home nation. The presence of Spanish troops in Iraq and the Spanish prime minister’s support for the ‘War on Terror’ were identified as the motivating factors for the bombings. In the face of the terrorist pressure Spain, for all intents and purposes, capitulated.

A second business continuity issue was the significant negative impact of the attacks across the European financial arena. The financial markets’ response to the Madrid bombings was initially negative and virtually all European stock markets fell following the news of the explosions. It is clear that as the day progressed the issue of the authorship of the attacks was seen as important and that doubts over whether or not ETA carried out the attack weighed heavily on the market.

The attacks reawakened fears of terrorism, with most European stock markets falling between 2% and 3% on 11 March 2004. Stocks dropped in London and in New York, with the Dow Jones diving after speculation of involvement by Al-Qaeda. In Tokyo, stocks opened lower the next day. Reuters summarised the fall in the markets in a series of interviews across several organisations: on 11 March 2004 Cema Marti, a manager at Ata Investment, was quoted as saying ‘Sales came with the fall in European bourses because of fears Al-Qaeda is behind the blasts in Madrid.’ Similarly Anita Griffin, investment director for European equities at Standard Life, stated, ‘This is a reaction on the day to terrible news of the bombs,’ and Jeremy Batstone of the brokers Fyshe Group said, ‘The market’s greatest fear was the Al-Qaeda network responding to the US led invasion of Iraq.’

The main security management issue identified by this incident was the need to closely monitor the link between terrorism and crime. Experts had identified that a convergence of international terrorism and transnational organised crime might take place somewhere in Western Europe. Police terrorism investigators had highlighted marked similarities in the behavioural and operational methods of terrorists and organised criminals. Unfortunately it was not regarded as sufficiently important to change the long-held view that the different goals of the two groups would prevent them working together, i.e. personal profit was the key determinant for criminals whereas terrorist were focused primarily on achieving political upheaval. The Spanish bombings showed this was no longer valid, as terrorist and criminal organisations were willing to co-operate over specific matters, in order to gain the benefits of economies of scale through working together.

‘One of the central members of the Madrid terror cell, Jamal Ahmidan, was a former international drug dealer who converted to Islam while in prison and tapped his criminal past after his release to supply the cell’s logistical needs—including the exchange of drugs for the explosives used in the attacks.’ – (Shelly, et al., 2005, p. 41).

A number of key issues emerged after the attacks – the reduction in immigration constraints, the need for effective communication networks and the need for good international cooperation. These are discussed in turn below.

The first area to consider was the need to re-examine the existing immigration laws because the Madrid bombings alerted the world to the proliferation of jihadi networks in Europe since 11 September 2001. Al-Qaeda had moved from focusing on African/Middle East operations to the European arena. It now actively provided encouragement and strategic orientation to scores of relatively autonomous European jihadi networks. These networks were marshalled for specific missions, drawing operatives from a pool of professionals and apprentices, and then dispersed. The Madrid bombers received radical teaching, advice, and assistance from imams and colleagues in Britain, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy and Norway as well as North Africa.

Based on secret recordings of militants and the arrest of suspects internationally, senior counterintelligence officials believe that post-9/11, wider support for the jihadi movement has allowed Islamic terrorists to significantly extend their European operations. The Spanish authorities expressed concern that liberal western immigration laws facilitate easy movement of potential jihadi terrorists and their arms. Minimal European international borders allowed Al-Qaeda and allied groups to travel freely across the continent, and relaxed immigration laws constrained the ability of the government to deport suspected terrorists. Such laws needed to be reviewed and effective movement controls established without creating a negative impact on the genuine movement of EU nationals for business and pleasure.

It is also evident that efficient communication between members of the emergency response teams is essential. The Madrid bombings clearly demonstrated the need for effective, speedy, adaptable, high volume communications networks which would operate on designated emergency channels. Quick and effective communication networks are vital to help reduce chaos and minimise the impact on the immediate environment and the wider economy, both during and after the incident.

The incumbent NATO chairman, General Harald Kujat, reported that the Spanish emergency medical response team reacted quickly and efficiently to the attacks. Disaster response and life-saving vehicles arrived within minutes and emergency response personnel made efforts to distribute the injured among a number of nearby hospitals. The third and fourth explosions caused some resource and personnel strain because almost all available resources had been devoted to dealing with the first two. The later explosions exceeded capacity for the emergency response teams, and this has become the aim of terrorist groups seeking to create maximum disruption. Kujat noted that the communications system must also allow for broadcast of clear messages from the emergency services and media to the wider public to minimise panic and control movement.

Finally for effective security and emergency planning there must be close co-operation between national and international law enforcement agencies. Mutual concern and discussion following incidents such as the Madrid bombings have resulted in the establishment of formal international agreements, including conventions, treaties, and memoranda of understanding. It is clear, however, that these agreements are not self-enforcing. Without law enforcement and judicial cooperation that results in investigation, prosecutions, and crime prevention, international agreements lack meaning in practice. The key point is that the implementation of such agreements is the real measure of the success of international cooperation.

‘The Madrid bombings led to attempts to galvanise Europe’s response to terrorism.’ – (BBC News, 2007).

One crucial outcome of the Madrid bombings was the conference organised by the United States Mission to NATO and the George C. Marshall Centre, supported by the Slovenian Foreign Ministry. From 27 June 2005 to 1 July 2005, an expert conference was held in Slovenia under the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) with the intent of identifying ‘Lessons Learned from Recent Terrorist Attacks: Building National Capabilities and Institutions’.

Following on from the NRC report, nine expert working groups were established. Composed of professionals working on specific areas related to the fight against terrorism, each group addressed in greater technical detail national policies and priorities in those areas, allowing for a unique exchange of information regarding what might be improved. Taking each subject area in turn, the groups reached the following recommendations and conclusions:

- Site security: while there is no single approach that can guarantee site security, enhanced and comprehensive intelligence gathering and sharing, improved use of available technologies (such as biometrics), and frequent training, exercises and simulations including both public and private sector agencies would be very beneficial.

- Medical preparedness and response: participants discussed ways in which NRC nations might wish to concentrate on improving training and qualifications for emergency medical personnel, such as producing operational guidelines based on common operative principles.

- Civil law enforcement and investigations: legal norms and the role and investigative methods of enforcement agencies in terrorist cases were discussed. Emphasis was placed on the need to share information and resources among both agencies and governments. The group analysed preventive measures aimed at anti-terrorism law enforcement, such as improving immigration laws, confronting hostile reconnaissance and fighting organised crime.

- Military roles and tasks: most participants noted that the military should play a supporting role in combating terrorism, including explosive detection, Chemical, Biological, Radiological & Nuclear (CBRN) defence, or training of relevant personnel.

- Airspace control & monitoring: experts exchanged views on specific anti-terrorist measures undertaken by NRC member states, such as improved radio and radar coverage, new procedures for intercepting airborne threats, visual warning systems and ground-based defence assets.

- Interagency and vertical co-ordination: the importance of devising a comprehensive approach to emergency planning, so as not to under-invest in non-terrorist emergency situations, the need to designate a lead agency early in the process and the importance of efficient communication was discussed.

- Building responsive legislation and institutions: legal experts discussed possible enhancements to national and international legal frameworks on terrorism, including existing export controls, transport and site security, regulation of financial transactions, immigration laws and extradition agreements, as well as terrorism-related UN Conventions and the EU Action Plan.

- Nature of terrorist organisations and operations: experts examined their national experiences and the evolution of terrorist cells and networks operating on their territory, their financing and resource management, as well as trans-border links.

- Hostage negotiation and rescue: psychological experts addressed this. They pointed to the tension between the general principle of refusing to negotiate with terrorists and the need to employ all available means to safeguard the lives of hostages.

The Madrid bombings hit Spain unexpectedly and led to a change of government. The incident negatively affected the European financial markets and demonstrated the willingness of terrorists and criminals to work together to mutual benefit. A review of immigration laws was demanded to reduce free movement of terrorist suspects and arms across Europe. It also highlighted the need for effective emergency communication networks and good cooperation between law enforcement organisations. The attack was the focus of the NATO conference of 2005 in Slovenia and it encouraged all European states to review their business continuity, security and emergency management plans and procedures.

London Underground and bus bombings, 2005

On Wednesday 6 July 2005 it was announced that the 2012 Olympic Games would be held in the UK. The whole country was celebrating an unexpected win in the close fought contest, and planning began almost immediately for this high profile, international event. Hardly had the announcement been made when more sinister and negative news dominated the headlines. The following day a series of bomb blasts in the heart of London killed 52 people and injured more than 700. Shortly before 9:00 am on the 7 July 2005, death and destruction resulted from the biggest terrorist attack in Britain since Lockerbie in 1988. It brutally punctured the Olympics euphoria. As a result Thursday 7 July, 2005 can be regarded as one of the darkest days in British history since the Second World War.

The Economist reported police statements that at least 33 people had been killed and hundreds injured by three explosions on London’s Underground. Eyewitnesses described huge explosions that sent glass flying and filled carriages with acrid smoke. Rescue workers had to use pickaxes to reach trapped passengers.

A further attack on a bus in Tavistock Square blew the roof off a double-decker which was travelling through Woburn Place in Bloomsbury. A previously unknown group calling itself the Secret Organisation, Al-Qaeda’s Jihad in Europe, claimed responsibility for the attacks citing the action as revenge for the British ‘military massacres’ in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In justifying the attack, the terrorists provided a 200 word statement published on an Islamic website. This group was previously unknown before the bombings and their website purported to carry statements from Al Qaeda. In short, the message said that:

‘The attack was against the British Zionist Crusader government in retaliation for the massacres Britain is committing in Iraq and Afghanistan.’ – (BBC News, 2005).

Time and again military and political leaders had predicted that an attack on the United Kingdom’s mainland was inevitable – a case of when, not if. By striking at London, the heart of international transport and finance, Al Qaeda hoped to achieve a three-pronged success which would damage continuity:

- First, it looked to disrupt the Group 8 summit meeting, attended by the most powerful leaders in the Western world. This was being hosted by the British prime minister at Gleneagles, Scotland. That aim failed.

- Second, Al Qaeda hoped to reproduce the ‘Spanish effect’ and alienate the public from its government, as it had so successfully done after the Madrid train bombs the previous year. Here, too, it failed, as is clear from the results of the next election.

- Third, it wanted to fracture the ‘special relationship’ between America and the United Kingdom, to break the partnership in Iraq by making the price of co-operation with America too costly to bear. This was never going to happen as the ties between both nations are too strong.

Although the attack was grave the economic impact was not even close to the devastation of the 9/11 attacks, mostly because of lessons learned from the 9/11 attacks but also for a number of other reasons. The foremost explanation is that the London attacks did not damage the financial infrastructure. There was limited immediate disruption to the national and world economy. There was no significant impact on trading in either the London Stock Exchange or the London Financial Futures, and the Options Exchange was not affected. In order to assess the result of the attacks on the financial system, calls were made within the central banks, finance ministries and leading financial institutions. Precautionary assessment was also conducted in the United States as British Treasury officials communicated with the US Federal Securities and Exchange Commission. Their initial findings were ratified by the Financial Services Sector Co-ordinating Council, a private-sector group set up after the 9/11 terrorist attacks to examine possible threats to the United States’ financial infrastructure.

The attacks understandably caused massive disruption to travel in and around London. The Underground and bus services were suspended and overland mainline railway stations closed. With the exception of Kings Cross, which was used as a makeshift hospital to treat casualties, and neighbouring St Pancras, mainline stations services along with London Transport buses restarted later in the day. The majority of the underground network reopened on 8 July. Use was made of river vessels as an alternative means of transport although many commuters making their way home had to walk to mainline stations.

The Kings Cross and St Pancras mainline stations reopened on 9 July. Disrupted underground services were gradually restored over the following four weeks with the Piccadilly line being the last to fully reopen on 4 August.

In April 2005, the London Resilience Team published the UK’s Strategic Emergency Plan (Version 2.1). Since the introduction of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 in 2005, all regions in England and Wales have been required to establish and maintain a Generic Regional Response Plan enabling the activation of regional crisis management when needed. In order to comply with the requirements of the Act this document performs as a signposting authority. It links to other relevant emergency plans, thus establishing a comprehensive and holistic Generic Regional Response Plan.

In effect, this plan is the basis upon which the UK first responders react to any major emergency or crisis, although this is not terrorism specific. After years of preparing for the worst, or something very close to it, the unexpected terrorist attack happened. Emergency planning proved crucial in the response to the London bombings. The emergency services were widely praised – by the Queen and the prime minister, among others. The opinion of the overwhelming majority was that their response had been swift and effective.

It is always possible to identify areas for improvement and a Home Office report partially published by the BBC summarises the emergency response. It identifies a number of shortcomings in the manner in which the emergency services responded to the situation. There was evidence that some information was suppressed; the police casualty bureau was overwhelmed by calls which were made worse by technical difficulties.

Investigative journalists found it extremely difficult to obtain reliable information about the number of casualties and their associated injuries, especially with regard to foreign nationals. Only the obviously injured were treated and there was little consideration of the emotional trauma associated with such an event. Details of what had happened were not collected from people caught up in the events and there was no mechanism to provide those involved with details of avenues for advice and support. Many individuals were left feeling forgotten or unimportant and there were limited medical emergency supplies available at rail and Underground stations for general first-aiders to treat minor injuries.

The report also reflects on the success of the response to the incident by the emergency and security agencies. It concluded that the emergency response was extremely good; but makes three key recommendations:

- Firstly with regard to communications, future emergency responders should not rely on mobile phone networks, which became heavily congested. The disabling of mobile phones to all but 999 calls could be counter-productive as calls to family can stop widespread panic and also pre-empt calls enquiring about the location and status of individuals. It was suggested that a dedicated digital communications network for emergency services across London was urgently needed.

- Secondly, it was apparent that there were insufficient medical supplies. The report recommended that a cache of supplies be placed at major transport hubs and regularly checked and maintained.

- Finally those responding to the attacks received a large number of requests for information from the government. To improve coordination in future it was suggested that all requests should go through senior coordinators, leaving those on the ground able to focus on their support to the crisis.

The suicide bombings were carried out by Muslim extremists, all of whom were British and none of whom had previous convictions. Only one, Mohammad Sidique Khan, had come onto MI5’s radar; their interest was taken up with what they considered to be more urgent and dangerous targets. Khan along with two of the other bombers, Hasib Hussain, and Shehzad Tanweer, had reportedly received terrorist training and religious instruction in Pakistan several months before. The fourth, Jamaican-born Jermaine Lindsey is believed to have converted to Islam in Afghanistan. All had been recruited or influenced deeply by Al Qaeda. This highlighted the need to consider ‘home-grown’ potential threats to the security of the UK when conducting security and emergency planning, rather than solely anticipating any terrorist activity to originate with external groups.

Within minutes of the bombings in London, ambulance, fire and police sirens could be heard throughout the city. The high visibility vests worn by rescue teams would subsequently dominate the images in international media coverage. Behind the scenes, ministers and security, emergency and health service officials executed a highly structured emergency strategy. As planned, the Home Office took primary responsibility for combating terrorism within the UK and the Home Secretary chaired the cabinet committees on terrorism, bringing together the work of ministers across the government.

Agreed emergency management and planning procedures made establishing the nature of the threat and tending to the injured the priority. The preparation for terrorist attacks which had already taken place proved vital in ensuring an effective and coordinated response. The security and emergency planning paid off and while ‘no plan survives contact with the enemy’, it became apparent on the day that the time spent ‘exercising’ and training for such an atrocity ensured that casualties and disruption across the city were kept to a minimum.

In conclusion, the tragic loss of life and the injuries sustained to those directly caught in the 7 July 2005 bombings touched the city, the nation and beyond. London is a historically resilient city. The disruption, however, both in terms of business continuity and the capital’s infrastructure, was minimal. The introduction of the UK’s Strategic Emergency Plan promoted swift and effective responses by the emergency services.

It is perhaps worth noting that London only had four explosions to deal with whereas Madrid had ten. Moreover, the London death toll was just 25%, and the injury rate only 30%, of Madrid’s. While the emergency services in London were commended for their effective response, could they have managed as well had the city been hit by as many bombs as Madrid? The Spanish emergency services did cope with the situation until the fifth bomb exploded.

Glasgow Airport bombing, 2007

The British Airports Authority (BAA), now rebranded Heathrow Airport Holdings, owns and operates a number of airports including Glasgow. This part of the study examines the bombing of Glasgow International Airport in 2007 by two men using a Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Device (VBIED). The terrorists Bilal Abdullah, a British born Muslim of Iraqi descent, and Kafeel Ahmed, a Muslim of Indian origin, were al Qaeda affiliated. Abdullah was a doctor based at the Royal Alexandria Hospital, Paisley, while Ahmed was studying for a PhD at Anglia Ruskin University. A suicide note subsequently discovered by the authorities indicated that the two men expected to die in the attack. This incident followed a failed attempt less than 24 h earlier by the same terrorist cell to explode two VBIEDs outside a popular London night club.

The day of the attack

On Saturday 30 June 2007 at 1:34 am, Kafeel Ahmed uploaded a suicide note and his will to his e-mail account.

At 8 am Ahmed and Abdullah constructed the VBIED at Houston near Glasgow by packing a four-wheel drive Jeep Cherokee with fuel, gas canisters and makeshift shrapnel before driving north to Loch Lomond. They remained there until 2 pm. During this time Ahmed sent a text message to his brother describing how his will could be retrieved.

Closed circuit television cameras situated around Glasgow International Airport recorded the terrorist’s vehicle arriving at 3:04 pm.

At approximately 3:13 pm and with Ahmed behind the wheel the suspects drove the Jeep into the doors of the main terminal building of the airport. The vehicle would have penetrated the terminal building had it not been for the security bollards outside the main doors. Ahmed tried to free the Jeep without success. Abdullah threw petrol bombs from the vehicle while Ahmed doused himself in petrol and set himself alight. Ablaze and with both the vehicle and terminal building now also on fire, Ahmed emerged from the Jeep and attempted to enter the terminal building on foot. Officers from Strathclyde Police supported by members of the public restrained him, along with his accomplice. After a brief struggle both Ahmed and Abdullah were detained by the police.

The terminal and additional areas of the building were efficiently cleared. Strathclyde Fire and Rescue Service initially attended the fire before being joined by BAA rescue and firefighting units. It was discovered that the vehicle contained several propane gas canisters with the intent of creating an incendiary bomb effect. Both the terminal and vehicle fires were brought under control within 15 min and had been extinguished after 30. A sprinkler system was activated by the fire, but the isolation valve could not be reached due to the close proximity of the fire and the existence of a crime scene. Consequently, large volumes of water continued to be pumped into the building for several hours. Neither the water nor smoke damage could be dealt with until the following day.

The crime scene was finally wrapped up by the emergency services and handed back to BAA after 54 h. Crichton notes that shortly before this incident an exclusion zone around a murder scene in Glasgow was in place for four weeks, but the airport reopened just 23 h and 59 min after the incident, with BAA initially working around the exclusion zone. It is worth noting that the emergency services will only lift an exclusion zone when they consider it safe to do so and the crime scene activities have been completed. In Glasgow’s case this was achieved in just over two days. In the case of the 1996 IRA Manchester bombing, the exclusion zone lasted for months and within six months of the incident, 250 companies were declared bankrupt.

‘Had the cargo detonated, a huge fireball would have swept through the building, with shrapnel killing and maiming many victims.’ – (Edwards, et al., 2007).

The airport handles over eight million passengers each year. With the school holidays having just started, they day of the attack was one of its busiest days on the calendar. In addition to the injured terrorists, fortunately no more than five members of the public were hurt in the incident. They were all taken to the Royal Alexandria Hospital, Paisley for treatment, approximately 3.5 miles away from the airport. A suspicious device was discovered on Ahmed when he was being treated and the hospital was partially evacuated. It was later found to be harmless. Ahmed suffered 90% burns to his body during the attack and died from his injuries two days later.

There were approximately 1,100 passengers held on board incoming aircraft for several hours after the incident occurred. This allowed the emergency services to evacuate circa 4,500 members of the public from the terminal building and transfer them to an emergency holding area. This location had been previously identified in the continuity plans and evacuees were relocated to the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre in central Glasgow, approximately 8.5 miles from the airport. Crime scene and police investigation protocols dictated that each person transferred to the holding centre had to be interviewed before being released by Strathclyde police.

Glasgow airport’s response

It is not unusual to find business continuity plans that are designed to deal with single incidents. Glasgow airport was no exception and it had no one plan that dealt with this particular scenario. Instead it had a series of integrated plans that addressed situations such as mass evacuation, closure of airport approach roads and mobilisation of off-duty staff. Within 45 min of the initial incident, the BAA crisis management team had become operational, with the recovery team in place one hour later.

Efforts had to be made to reopen the airport as early as possible and a system of communication and coordination had to be established with other key stakeholders to accomplish this. Some airlines had already decided to cancel flights into and out of the airport and this had to be incorporated into these communications.

Each business unit within the airport environment is required to have a documented and clear contingency plan, all of which have been incorporated into the main BAA contingency planning. BAA’s strategy is centred on the ‘7 Rs’ method that incorporates:

- Risk: an evaluation of the financial, operational and strategic risks to BAA and its key stakeholders.

- Resilience: the ability to positively adapt to change, transform experiences or situations to the organisation’s advantage, and emerge stronger from doing so.

- Rehearse: the various drills and test situations that key stakeholders have to incorporate into contingency planning in order to hone reaction times and methods.

- Responses: a documented, measured set of constantly reviewed strategic, tactical and operational reactions to given risk-assessed situations.

- Recovery: these are the various activities and tasks necessary to resume normal operations.

- Review: the cyclic system of re-examination of risk assessments, the allocation of resources and the involvement of key stakeholders within the contingency planning systems within the organisation.

- Reputation: every business needs to be aware of how they are perceived. A negative perception can affect areas of business such as recruitment and investment as well as the sales performance of the organisation.

Media

Any organisation that ignores the importance of positive media relations can suffer as a result. This can hinder the return to normal operations. Air transport is regarded as immensely newsworthy by the editors of newspapers, magazines and television broadcasts. During the first 24 h after the incident, the BAA media relations team handled somewhere in the region of 800 calls.

‘The week following the incident, Glasgow Airport website received 130,000 visits compared to 6,000 the previous week.’ – (Crichton, 2007, p. 4).

It follows that, during this high profile media incident, BAA would look to pro-actively protect the image of Glasgow International Airport. Despite being the victim of a terrorist attack, it would want to avoid any undue criticism over its handling of the situation. It achieved this very effectively by maximising the use of a number of media channels including its own website, e-bulletins, a local radio campaign plus using the Glasgow city centre big screens. It also ensured that Scottish members of parliament were kept well briefed.

Impact on travellers

Commercial flight cancellation is something of an occupational hazard for airlines and can happen for any one of a number of reasons. Usually only individual flights are affected. In addition to terrorist attacks, however, other scenarios such as adverse weather, volcanic ash clouds or air traffic control strikes can seriously disrupt aviation operations or even cause complete airport shutdowns.

‘The problem for a lot of people whose flights have been cancelled is that you don’t automatically go on the next plane, you actually go to the back of the queue.’ – Simon Calder, Travel Editor, The Independent.

Anyone booking their flights and hotels separately may find that while the airline is legally obliged to refund them or offer a suitable alternative, hotels may insist on being paid. Package holidays do provide better protection as travel companies must either give you a full refund or offer an appropriate alternative.

The immediate aftermath

Both Liverpool’s John Lennon airport and Blackpool airport were initially closed and security was tightened at other UK airports. Security at airports in the USA was also intensified in response to the Glasgow incident. The attack resulted in wide-ranging global changes regarding vehicle access to airports which included extensive deployment of hostile vehicle mitigation measures.

‘We have a long way to go before airports here in the UK are secure enough to prevent the prospect of another terrorist attack.’ – Chris Yates, security consultant (BBC News, 2008).

Despite the severity of the attack, the airport reopened 24 h later. Twelve months on, a reported £4 million of additional funds had been spent improving the airport’s security. This included around 300 steel hostile vehicle mitigation barriers. Even so, security specialist observed that although some weak points in airport security had been addressed, others remained.

The economic cost of terrorism

The Israel Interdisciplinary Centre in Herzliya, Israel has been studying the effects of terrorist attacks on the economy for many years. The centre has determined that although one single event such as the London bombings cannot be used to gauge economic impact, there is enough data to draw some conclusions. One of their conclusions tells us that terrorism as a global trend is having an impact on the economy.

‘From an economic point of view, terrorism works. For a relatively small investment terrorists obtain a large economic impact. . . Gradually the global economy is being hurt by the constant threat of terrorism and the attacks.’ – (International Institute for Counter Terrorism, 2010).

The economic cost of terrorism can be divided into short, medium and long term. In the short term there are several direct costs such as the loss of human life, victim support, loss of property, cost of the attending emergency services, cost of removing debris and losses due to economic activites interrupted by an attack. He further identifies short term indirect costs such as the effect on tourism, hotel occupancy, theatre and cinema attendance figures and reduced restaurant bookings generated by a consumer fear of further attacks.

In the medium and long term there is reduced investment and economic growth, not to mention the ever-increasing cost of anti-terrorism measures. Sustained attacks (as experienced in Northern Ireland and Israel) can effectively destroy the tourism industry while one-off incidents tend to be quickly forgotten.

‘During the Troubles, tourism just died.’ – Martin Mulholland, Concierge Europa Hotel, Belfast, 2012.

The economic costs relating to the Glasgow attack are the least complex of the three incidents. The cost of policing the attack was put at £1.7 million while physical damage to the airport is reported to be in the order of £4 million. The actual loss of business was considered minimal as the airport reopened within 24 h of the incident. We must not, however, lose sight of the fact that the terrorists’ incendiary device failed to detonate.

No figures are available regarding the loss of income for the shopping outlets, bars, cafes and restaurants based at Glasgow, or for any airlines or airline-dependent suppliers such as caterers. It is assumed that their respective operations will have resumed when the airport reopened for business.

In Madrid, the attacks caused material damages of about 17 million Euros but the additional economic cost has been estimated at more than 282 million Euros. The Madrid train bombings were not only the most devastating act of terrorism in modern Spain but also across Western Europe.

In London, it was London Transport that bore the brunt of the attacks, resulting in a negligible immediate impact to the broader economy. It is clear that the British economy was affected by these bombings in the long term, with an estimated subsequent cost to the capital’s tourist industry of approximately £4 billion, although tourism across the remainder of the UK witnessed an increase in its 2006 revenue figures. Confidence in London tourism was probably further dented by the subsequent failed attacks on the London Underground network only two weeks later.

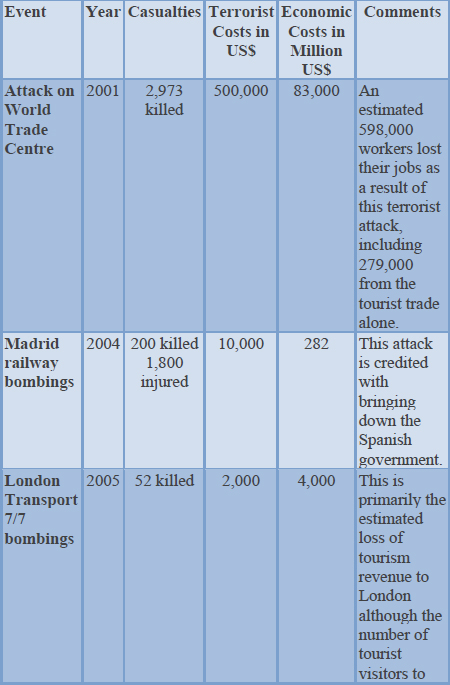

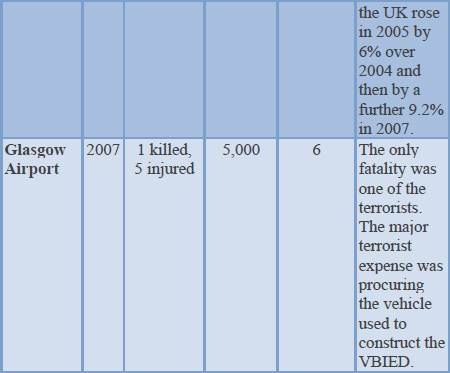

Figure 14 is based upon the Al Qaeda attacks on Madrid (2004), London (2005), Glasgow (2007) plus the 9/11 World Trade Centre attack. It illustrates that while the cost of terrorist attacks is generally reducing, the resulting economic cost is soaring. The expenditure required in financing a terrorist attack is also generally small in comparison with the resultant economic damage.

Figure 14: Cost of terrorism versus related economic costs

The exception in terms of terrorist costs is the 9/11 operation. In this instance, however, the number of casualties was far higher than any previous attack and the economic impact was unprecedented.

When considering the ‘terrorist costs’ and the corresponding ‘economic costs’, people could be forgiven for thinking that the best return on investment (ROI) for the terrorists in recent times was the 9/11 attacks. Figure 15, overleaf, demonstrates that while the 9/11 attack achieved a 166,000 to 1 ROI, the London 7/7 bombings generated a staggering 2,000,000 to 1 return. Meanwhile, Glasgow hardly registers when compared with the other featured attacks.

Figure 15: Terrorist’s return on investment -v- economic costs of attacks

While the cost of terrorism can be quantified in terms of casualties and economics, the intangible terrorist objective of generating fear cannot.

Conversely, on a positive note, 7/7 did witness some business beneficiaries, especially security firms, taxis and bicycle stores. In fact, as one observer noted: ‘safety and security seem to be converging.’

Lessons learned

Terrorism is considered a Tier One threat by the UK and it is taken just as seriously in many other countries. In general, transport presents a soft terrorist target and there is no single method of guaranteeing the protection for more open modes such as trains and buses.

Glasgow Airport was the first terrorist attack on Scottish soil. Conversely, London has been dealing with terrorism for over 150 years while Spain has had to tolerate the unwanted attention of ETA for decades. The Madrid bombing also demonstrated that terrorist and criminal elements are prepared to cooperate with each other to further their own ends, with explosives being traded for drugs.

Both the London and Glasgow bombings were suicide attacks. Moreover, when you take account of the failed attack on the London Underground on 21 July 2005, at least eleven jihadists have been prepared to martyr themselves at the expense of the British travelling public. This of course excludes other foiled plots such as that of Richard Wright, the shoe bomber, and the liquid bomb plot, both of which intended to blow up transatlantic flights.

While businesses may not be the specific target of a terrorist attack, they can still suffer from collateral damage. The impact could be in the form of exclusion zones, damaged property, injured, killed or traumatised staff, transport disruption, supply chain failures, etc. Furthermore, with so much glass used in the design of modern buildings, a relatively small explosion could still cause substantial casualties from flying glass. The deployment of comparatively inexpensive anti-shatter plastic film would certainly help mitigate the risk. Businesses could also suffer if they are located in areas considered to be at a high risk from terrorism. The tourism and hospitality industries both suffered in London and Madrid following the bombings.

Following the failed Glasgow attack, hostile vehicle mitigation (HVM) measures have been deployed at airports within the UK and beyond, sometimes in the form of ugly steel barriers or concrete blocks, sometimes designed to appear like attractive seats or planters. But whatever their appearance, the vital criteria is that they work. In fact HVM solutions are becoming more widespread as companies also look to negate the efforts of ram-raiders.

It is clearly not the responsibility of individual businesses to detect or apprehend terrorists – that is the work of the national security services. It is their responsibility though to protect their businesses and staff as effectively as is possible. Moreover, we must not forget that while they were at the forefront of each of the three terrorist attacks, the emergency services are not just there to react to such events. In addition to their respective ‘day jobs’, they are also expected to respond to other, non-terrorist situations such as natural disasters.

It could have been worse

While all four bombs were successfully detonated in London on 7/7, the bomb targeting Glasgow Airport and three of the 13 Madrid bombs did not. With the emergency services in Madrid over extended after the fourth explosion, not only would there have been more fatalities had all bombs detonated, but scores of additional injured would have been left unattended.

As for Glasgow, we can only speculate. With hundreds of travellers in the terminal building it would be reasonable to assume many potential casualties. In the aftermath, Glasgow Airport would probably have needed rebuilding rather than repairing and its recovery plans would have been tested to the limit.

What went well

- The Spanish emergency services had effective, adaptable, high volume communications networks which operated on designated emergency channels.

- The Madrid bombings resulted in better international cooperation to help plan against and prevent future attacks.

- The emergency services in London were very highly praised for their efforts.

- Glasgow Airport’s plan went well. Much benefit was derived from the extensive testing of their plans, as the reopening of the airport within 24 h demonstrates. With key staff effectively on round-the-clock emergency call-out, mobilising additional resources to deal with the incident was particularly successful. Easy access to appropriate contact details was of paramount importance. Their media plan was well thought out and they were pro-active in their communications. The airport’s vehicle access denial plan was also implemented in the aftermath to restrict access to the terminal’s inner forecourt until necessary security measures were applied.

What could have been done better

- The Spanish Government fell, probably as a result of the attack.

- Spanish emergency services struggled to cope with the number of casualties across multiple locations.

- The Spanish authorities should have more closely monitored the link between terrorism and crime.

- The financial markets reacted badly when it was discovered that al Qaeda and not ETA was behind the Madrid attacks.

- Both the Spanish and British governments should have paid more attention to the risk from home-grown Islamic terrorists. Glasgow Airport coped well with the crisis. Had the device brought by the terrorist gone off, however, it could have been a very different story.

What did not go well

- The Spanish emergency services coped well with the initial blasts, but were unprepared to deal with the scale of the Madrid bombing attack.

- In London, communications proved nigh on impossible as the Underground network lacked any mobile phone or wireless facilities. The police phone network proved unable to deal with the volume of calls.

- Insufficient medical supplies were available in locations close to the London attacks.

Conclusion

Every business, large or small, needs to embrace business continuity taking account of any potential terrorist threat they may face. They should keep in mind the damage caused by a terrorist bombing may be similar to that of an accidental explosion or a fire, potentially resulting in business inhibitors like denial of access and temporary or permanent loss of staff through fatalities, injuries or trauma.