2

From Global Governance to IS Governance

In Chapter 1, we saw that technological change had implications regarding the number of stakeholders involved in IS governance and the roles they play. We also highlighted the need for IS stakeholders to be appropriately positioned in line with the chosen development path in terms of information systems. In Chapter 2, we will put forward an integral vision of the organization as a whole. The purpose of this chapter is to take global organizational governance as our starting point and deduce from that the purpose and nature of IS governance. This will lead us on to a consideration of the coherence of organizational models on these two levels of governance and to questions relating to the dual status of information systems. In fact, information systems provide perceptional tools for both the internal and external environment of an organization (feedback systems) and action models for this same environment (service production systems), all at the same time. This means the quality of global governance may suffer in the case of poor IS governance. After reviewing the challenges of global governance, we will then define IS governance and its objectives. We can then consider IS governance viewed through several possible scenarios: an outsourcing strategy, the potential pooling of resources and a joint-management strategy with third-party stakeholders. This will enable us to form a conclusion as regards the need to be able to integrate these multiple dimensions within a single approach.

2.1. From organizational governance to IS governance

Consideration of the problems of governance goes back to the 1930s, with the work of Berle and Means [BER 67]. These authors warned of what they felt to be an imbalance of power between shareholders (owners of capital) and directors (business managers) in large, listed US companies. They demonstrated that these two types of stakeholders are in an asymmetric situation in terms of information. Directors have privileged access to the corporate information system and know how it works. Shareholders are excluded. The demand for governance was thus born with the discovery of a requirement for monitoring and counter-power. The natural consequence was the creation of systems to monitor management and the implementation of stock market and accounting regulations (creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission – SEC, in 1934).

In the 1980s, Williamson marked out the boundaries of corporate governance by making the distinction between three institutions: the market, the firm and the network. Williamson’s premise was that these three institutions are sufficient to coordinate all economic activities [WIL 75]. Using this approach, he posited the existence of three modes of governance:

- – the first is based on externalizing decisions by reference to market mechanisms for which the adjustment parameter is price (where supply meets demand). This model is characterized by an apparent absence of strategy at organizational level. Stakeholders are guided by the “invisible hand” of Adam Smith (1776). In this scenario, we can adopt Hirschman’s view that the firm is a price taker [HIR 70]. An external factor, in this case the pricing system, compels the company to adjust and regulate its production;

- – the second governance model is based on a hierarchical and functional organization characterized by the introduction of a corporate management, of some form of strategy (not limited to adapting to a price set by the market) and implementation thereof. The implicit suggestion here is that internal performance is driven by the control of human activities by the hierarchy [CHA 77];

- – the third model relates to hybrid or contractual forms that form the link between the market and the internal hierarchy. In this model, unlike the previous two, the manager considers that not all the value creation activities (core or support) are necessarily controlled by the same owners [POR 85] and the owners do not need to control them, and this was the precursor to widespread policies of outsourcing all or part of the value-creation process.

Thus, we can see that the issue of information (and information systems) is central to the question of governance. Central, because access to information will condition the asymmetries between the shareholders as principals and the directors as agents. The purpose of governance is therefore to provide a framework for the directors’ actions to encourage them to manage the company in the shareholders’ interests. Therefore, information systems will be used by the controlling parties in hierarchical organizations and by hybrid organizations with the introduction of extended information systems.

In both cases, the governance institutions, classically represented by shareholders’ assemblies and the board of directors, will play a major role in establishing a balance between compliance processes and performance processes.

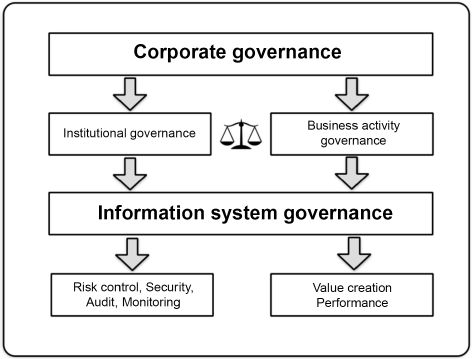

Figure 2.1. Corporate governance according to COSO (as per IGSI, 2005)1

2.1.1. COSO standards

COSO standards (1992, COSO 2 in 2002), established by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (USA), provide a benchmark for internal monitoring and a framework to measure the efficiency of an organization. We will see later how IS governance, following the same pattern as corporate governance, can find a balance using COSO’s two objectives as its pivotal point. The standard provides for institutional governance, on the one hand, which acts as a process guarantor (conformity, control, accountability, legality), and business governance on the other hand, which covers the organizational performance processes (value creation, business opportunities). A standard such as this facilitates value creation by leveraging decision-making processes aligned towards the efficient and effective use of resources.

2.1.2. The Sarbanes–Oxley Act

The quest for institutional governance is based on the regulatory framework deriving from the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in the USA. SOX was passed by the United States Congress in 2002. Its objective is to prevent fraud by promoting financial transparency in order to protect investors’ interests. It addresses accounting for listed companies. The introduction of this law was connected to various high-profile financial scandals, such as Enron and Worldcom. This law seeks to make businesses accountable by promoting integrity in accounting principles: Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (US GAAP).

The law sets out various principles:

- – certified accounts must be signed by the CEO and CFO as a legal requirement;

- – the mandatory content of reports is extended to include off-balance sheet items, auditors’ report, internal audit report and code of ethics;

- – the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is responsible for verifying the proper operation of listed companies;

- – an audit committee is established to oversee auditors, and audit rules are defined, as is the obligation to change external auditors regularly;

- – the creation of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) allows general oversight of audit firms and standards. This body also has the power when necessary to sanction actors (individuals or legal entities) for unacceptable behavior;

- – heavy criminal penalties are prescribed for the falsification of financial statements;

- – internal audits must be adapted to new requirements, and COSO is the common framework adopted to support internal audits’ compliance with legal requirements.

SOX has direct and indirect consequences for information systems. Elements of SOX have a direct bearing on obligations within the scope of IS management. Specifically, these include sections 409 Real Time Issuer Disclosure and 404 Management Assessment of Internal Controls. Section 409 deals with the ability of information systems to bring accounts to closure within two days. Section 404 meanwhile deals with information systems security, such as the management of user passwords, firewalls, cryptography, antivirus, backup, vulnerability assessments, service continuity, etc.

A similar law, the Law on Financial Security (Loi sur la sécurité financière – LSF), was passed in France in 2003. The LSF reinforces the legal provisions on corporate governance. In order to respond effectively to these regulatory constraints, organizations engage in the implementation of good practice and the use of international standards to ensure compliance.

2.2. Defining IS governance

IS governance is part of the quest for a balance between institutional governance and business governance. In response to this quest, a schema proposed by the IGSI2 demonstrates that IS governance consists of the definition and management of a set of processes serving the goals of business governance. In a transposition of the COSO principles of corporate governance at IS management committee level, IS governance thus clearly suggests the alignment of the IS management committee with organizational strategy. IS governance therefore supports both institutional governance, by controlling regulatory and compliance risks – security, audit, monitoring – and, at the same time, business governance, through the quest for value creation and improved business performance.

To achieve these objectives, IS governance proposes good practice guides: Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT) to define information systems governance, control and audit objectives; versus risk control; Global Technology Audit Guide (GTAG) for internal audit arrangements; and International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission – ISO/IEC 38500 for Corporate Governance of Information Technology. For the definition and measurement of value creation, IS governance proposes the use of tools like IT Scorecard and benchmarks that are more open to innovation and investment, such as ValIT, now included in V5 COBIT, Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI), Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL), Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) and International Organization for Standardization (ISO 27000). Matrix approaches are possible between different standards such as COBIT/ITIL or COBIT/PMBOK.

While many companies recognize the benefits of information technology, only a few have yet taken stock of, and managed, the risks associated with its implementation. For IGSI, IS governance is seen as a way to optimize investment in ICT in order to:

- – manage the risks inherent in information systems and implement a security policy;

- – enhance the performance of information systems processes and their customer focus;

- – align information systems with the company’s business processes and ensure that they contribute to business performance;

- – manage this performance by controlling the financial aspects, i.e. costs and gains related to the IS function;

- – predict the development of technological solutions and stakeholder skills based on projections and business development plans;

- – globally, support the objectives of value creation, i.e. the capacity of information systems to contribute to optimization of the value chain by its ability to innovate through new competitive edges (see Chapter 8).

2.3. IS governance in an outsourcing strategy

The transactional approach implies a phase of defining the operating forces, their responsibilities and their functions. This phase is associated with a process of financial valorization culminating in the taking of an aligned decision based on the financial cost analysis.

The issue of transaction costs was highlighted by R. Coase in 1937 [COA 37], then taken up by Williamson, the 2009 Nobel Prize winner [WIL 02]. The transaction costs theory is based on the concept put forward by H. Simon that economic stakeholders are limited in their thinking [SIM 80] and struggle to foresee all the costs associated with an activity. These authors show that there are often hidden costs associated with market forces. Thus, they highlight:

- – the costs of research and information-gathering upstream of signing a contract (market studies, feasibility studies, prospecting);

- – negotiation and decision-making costs (drafting, checking and signing a contract);

- – monitoring and enforcement costs (downstream of signing a contract).

The latter factors condition the setting up of ongoing monitoring and quality control of the service provided by the contractor.

These authors take the view that knowing transaction costs thus makes it possible to make an informed choice between keeping the activity in-house or outsourcing. In one case, transaction costs are high and justify the activity being carried out under internal hierarchical control. In the other case, transaction costs are low and it makes sense to leverage the market. Retrospectively, this line of thought can be used to explain companies’ presence facing the market.

It is clear that the issue of information management (and thus of information systems) lies at the heart of the transaction costs approach. Three consequences arise from this:

- – knowledge of transaction costs presupposes that companies are implementing an efficient information system. This must be able to provide traceability on these costs by linking particularly with management control procedures;

- – management control is exercised on the IS management committee, which must be in a position to estimate its own transaction costs. Information systems managers are thus themselves led to consider outsourcing the information system;

- – information systems are internal and external vectors for new forms of collaborative working. The development of open architectures and the Internet has had the effect of focusing on reducing transaction costs. The emergence of an open-source software economy, then a collaborative economy, has shown that it is possible to set up networks without a formal hierarchy. Between hierarchy and market, information systems have made it possible to develop the hybrid networking structures that the transaction cost theory had anticipated.

Thus, IS governance built around the transaction cost issue leads to:

- – frequent recourse to outsourcing, to the point of becoming systemic;

- – the establishment of a dual strategy, one to manage internal services and the other to manage outsourced services;

- – a quest for cost savings that involves managing a plurality of service providers.

2.3.1. The scope of outsourcing and the stakeholders involved

Making use of facilities management for information systems is a common practice within organizations. However, application parameters are variable insofar as the objectives and forms of outsourcing vary from one organization to another and develop along with technological changes and degrees of connectivity. In terms of features and services, the most common are the outsourcing of customer relationship management, human resources and accounting information systems. In terms of type, facilities management is most frequent for hardware outsourcing (computer hardware, servers, network connections, etc.) and third-party maintenance. However, many other forms of facilities management are emerging on an ongoing basis: business process outsourcing (BPO) (outsourcing a section of business activities, such as HR). The most common outsourcing tool is cloud computing, whether private, public or hybrid, joint venture or technology partnership (see Chapter 6). These new forms of outsourcing have an ongoing impact on the IS management committee’s territory and thus on the definition of the role of its stakeholders and also their governance (see Chapter 4). Strongly rooted and orchestrated by a financial-type transactional approach, the massive spread of outsourcing significantly redefines the role of IS management committee actors.

2.3.2. A dual strategy

The management of governance in a transactional prism leads to a dual perspective, in that it must overarch the management of outsourced and in-house services. The challenge for an IS management committee operating in this operating mode therefore lies in managing this duality. Often, agreements on functional cover, shared responsibility and also maintenance management differ from one provider to another. Moreover, the scope of services developed and maintained in-house can sometimes be blurred or poorly documented. Finally, the functional split resulting from an outsourcing approach based on a financial model is not always appropriate in operational terms. This dual strategy involves a special effort in managing the sharing of responsibilities. Essentially, the challenge is how to assure a stable and satisfactory level of services for users while achieving scalability of the information system as a whole and service continuity.

Subcontracting, formerly restricted to the hardware and network connectivity aspects, now extends to functional and application areas that are as vast as they are shifting. A lot of organizations have taken the decision to outsource many of their applications, including email and shared calendar management, and also the management of shared documents. These are classed as services and hence the term Software as a Service (SaaS). The concept of outsourced (and very often paid-for) application services is no longer limited to communication and storage services, but also extends into the heart of business organizations. This is particularly the case for publishers in terms of enterprise resource planning (ERP) software packages that provide contractual solutions with their customers across increasingly broad functional parameters, along with the potential for extended interfacing with other software packages covering services that are not integrated (or not supported) within the ERP.

For the target organization, or client, the development of these multiple contracts covering services and deliverables brings significant disruption for stakeholders both internal and external to the IS management committee. The race to contract-out is seen by the IS directors and other directors as a solution to the quest for agility in information systems. This is in fact the advantage of shifting the responsibility for applications outside the IS management committee’s territory. Thus, tasks such as maintenance, security and application updates are taken care of by external providers, skilled in their sphere of activities and able to provide appropriate state-of-the-art solutions.

As part of the process of negotiating service level agreements (SLAs), the internal stakeholders in the information systems management committee define the sharing of responsibilities with all the service providers in their network. In such contracts, providers agree on a set of measurable factors, key performance indicators (KPIs), such as the robustness, maintenance and development of leased solutions. This then results in an ultra-specialization of the organization’s external stakeholders, acting in the interests of the organization giving the orders. Internally, this means that the IS management committee’s role is evolving towards multi-project management.

2.3.3. Transactional governance

The race for subcontracting must be informed by the need to differentiate application-heavy processes, such as the in-house deployment of an integrated management software package like ERP on premise (treated as capital expenditure – Capex) and paid-monthly services such as public cloud email clients (treated as operational expenditure – Opex). These types of software are often combined within organizations. The development of Software as a Service (SaaS) tends to make it easier to arbitrate.

Often, the purchase cost is less than the cost of leasing a service. However, when we include the indirect or consequential expenses related to using the purchased software, and hardware support (space taken up, electricity, air conditioning, equipment management, managing its renewal, managing its maintenance, service updates), the bottom line can change. In a crisis economy, companies tend to move towards operating expenditure (Opex), because access to investment finance is difficult. In a booming economy, companies are more likely to opt for Capex. This general trend naturally impacts the IS management committee’s budget and its expenditure policy. Facility outsourcing has the advantage of making it possible to adjust the fixed costs and provides a clear answer to the question of the cost of providing services. Transactional governance is centered on the steering committee that deals with facility management contracts and their cost management. In the case of an organization that sees itself as operating a transactional strategy, the approach to value creation through cost optimization is thus central. This vision of IS stakeholder governance will determine the parameters of outsourcing and define where the organization draws the line between internal (what it does) and external (what it has done). The structure of stakeholder governance will thus be oriented and institutionalized around this pivotal point.

The main problem with this type of governance is being able to monitor and steer the facility management contracts. Fora will therefore tend to exclude, de facto, outsourced project management. Governance fora should thus subscribe to a technological and operational watch in order to be able to respond to the necessary technical developments. The emphasis will in this case be placed on governance fora in their ability to monitor at the local level:

- – service level requests (SLRs) to define requirements and service levels;

- – service level agreements (SLAs) to establish a link between service levels and IS client expectations;

- – service level management (SLM) to manage IS service levels;

- – key performance indicators (KPIs) to monitor the performance of the services cataloged in outsourcing contracts.

2.4. IS governance in a resource pooling strategy

In a resource pooling strategy, the information systems management committee organizes the provision of services to its customers via partners and subcontractors providing level-one services and who are themselves in control of level-two service providers. The clearly stated strategy of the information systems management committee is thus archetypal of leader firm governance, the strategy of a vertically structured (V-form) business as described by Aoki (see Chapter 1) that seeks to be in control and not to be subjected to flux with its service providers. As an extension to the transaction cost theory, Aoki’s work is of interest in this context insofar as it opens the door to hybrid forms between hierarchy and market [AOK 01].

The Aokian firm is conceived as a coalition deriving from an inter-organizational partnership approach. The company is seen as an association of directors and stakeholders (shareholders, employees, lenders, customers and suppliers). Governance is viewed as a set of constraints and rules, creating a framework for decision-making by the directors. According to Aoki, the objective is to understand how your own value can be created and shared. Governance is envisioned as the facilitator of this role, as an innovation system [AOK 10].

One of the singular points of the Aokian model lifts one limit to the transactional approach. Alongside the quest for monetary benefits driven by transactional analysis, Aoki introduced the concept of the value or quasi-value of the relationship, the fruits of a long cooperative relationship between stakeholders.

2.4.1. Hybrid forms between hierarchy and market

Aoki has studied network organizations in the J-form group, whether of the V-form or the H-form type. If we follow Aoki’s thinking, IS stakeholders are regarded as a collection of interests to be pooled. This means that their governance should not seek to separate them, but on the contrary to unite them so that they can act in harmony. This is characterized by governances formed from alliances, partnerships, unions and collaborations.

These studies show the pertinence of a horizontal operation of the firm, where all stakeholders form an alliance and organize themselves into a shared governance structure. The flexibility and agility of the partner network are promoted. The focus is thus put on internal partnerships with a strong return on investment. Partnerships are formed and dissolved in line with the services required by business activities. Each stakeholder is sovereign within their sphere of action, but they all work in unison towards the fulfillment of a joint, concerted, productive project. Partnerships are vectors of social cohesion and organizational coherence.

Pooling here makes reference to win–win strategies. These non-zero games are aimed at reducing the uncertainty resulting from this kind of cooperation. Pooling can limit the information asymmetry between stakeholders and promotes savings of time, means and resources. The issue of empowerment as a profitable investment positions the information system as a catalyst. It is considered an instrument whose governance is at the service of the stakeholders who use it in a positive interaction leading to organizational learning and increased capacity for action.

2.4.2. Self-organized forms

The pooling of information systems can be fulfilled by fluid, flexible processes that maximize the horizontal organization. This then fully exploits the potential of ICT systems. In a self-organizing strategy, the organization acts like a community of stakeholders adopting the rhizome paradigm [DEL 80]. Collaboration between stakeholders is based on adaptable, flexible models. Agile approaches using few resources are preferred.

The organizational issue in this case is to distribute the knowledge that has been created to a wide variety of stakeholders. Thus, IS plays a key role [SCH 14a]. The use of tools that help keep physical meetings to a minimum is favored. Collaboration supports action. Governance processes are not defined in absolute terms, but in terms of contingent need. Organizational principles are founded on ad hoc approaches and on modular and open tools. The stated objective is to maintain the lightest possible operating model to focus on innovation with the emphasis on economy of resources. Stakeholders form a coalition if necessary to make the organizational structure sustainable.

However, such a structural arrangement is also envisioned as a learning organization [ARG 78, SEN 90, ZAR 00], and the focus is on knowledge capitalization and continuous improvement strategies. Carried through to its conclusion in technological environments, such as software development, this pooling and sharing strategy has showed astonishing organizational capabilities, as evidenced by the success of open-source software.

2.5. IS governance in a co-management strategy with stakeholders

When we regard IS stakeholders as being of strategic importance, IS governance takes on a partnership aspect. The prism of transaction costs or pooling operations is not eliminated as such, but it is no longer a decisive factor in decision-making. The idea is to not reduce the complexity of interests at stake by marginalizing certain peripheral actors. The partnership approach to IS stakeholders is influenced by the seeking out of hidden costs and the desire to make them transparent. The issue of governance thus unfolds across a wider and more open playing field. In a context such as this, the first issue to be considered is the stakeholders who have been forgotten or sidelined, and also to listen to the plurality of this group. In highly competitive universes, this special attention can be a powerful lever to drive operational innovation. This, of course, happens through stakeholder governance based on the mobilization of actors and through a strong recognition of their contributions. It also happens through taking into account the interdependence of the stakeholders in IS governance and implementing mechanisms of co-construction and co-decision. This level of openness may lead to a closer relationship between IS governance and human resources.

2.5.1. The forgotten stakeholders

IS governance is not immune to the mistakes repeatedly made by management. In focusing on efficiency, or simply responding to the pressing injunctions of senior management, some stakeholders may get neglected. This can happen to an information systems customer, an important figure in the marketing strategy but also an often-ignored figure in internal strategic decisions. Significant progress has been made in IS management through the widespread adoption of Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) certification and good practice. Identifying an internal customer, defining a deliverable, agreeing a service contract, supporting change and providing a Service and Support Center are all processes that have been standardized to improve the professionalization and industrialization of IS management committees.

All this naturally entails significant cost, but the cost of not taking account of client needs can still be higher, as has been shown by the total cost of ownership (TCO) approach of the Gartner Group. When customers are neglected, they will try to find their own solutions, to get around the problem. This results in significant costs, which can remain totally unknown in the absence of a partnership governance of IS stakeholders. Another stakeholder too often ignored by governance is the end user. To put it bluntly, their existence is sometimes ignored until it is time to distribute and implement a new computer application. At this point, they will be accused of resisting a sudden and sometimes brutal change. The information systems management committee will then make it their mission to force the end user to give in and adopt the solutions imposed on them.

The responses do not all come via training programs and support teams in the event of major infrastructure migrations. It is necessary to design a governance that allows users and beneficiaries to become involved and mobilized at the earliest possible stage. We can note some developments in this direction with the widespread dissemination of agile methodologies such as Scrum and XP, in which the end customer is involved throughout the process. To summarize, adopting a partnership governance also means refusing to make IS stakeholders actors take sides against each other, refusing to marginalize IS beneficiaries in the face of shareholder demands and refusing to sideline the user against the decision-makers.

2.5.2. Recognizing stakeholder contributions

Once set up, governance forums do not only have an operational role. Being authorized to sit on this or that committee, and being able to participate in decision-making at this or that stage in the development of an IS project, is a way of achieving recognition of one’s abilities from others. Governing IS stakeholders thus means, for the CIO, being able to bring them together around the table and create an environment conducive to reflective discussion. This involves setting out to make a critical and attentive reading of the information system on the basis of an initial diagnosis. Questions can then be asked: How do we take into account the business needs of stakeholders from different environments and with different levels of responsibility? Are all users represented in the fora? If yes, at what level? For what purpose? What account is taken of external partners resulting from extended enterprise strategies? So many questions, so many findings. Finally, an analysis of the functioning of the governance fora of stakeholders on the strategic level can be an instrument for the implementation of a proactive organizational model.

The better developed, formalized, communicated and understood governance is, the more it allows stakeholders to appreciate the importance and the advantages of their interdependence. This appreciation can limit the instrumentation of fora for the purposes of internal politics and power grabs by a minority. When governance is dealing with a truly collective project, it can equate to joint identification of the challenges, joint financial decision-making and joint action in the field [BAL 06]. To bring us back to the title of this paragraph, it is necessary to bring about a situation where stakeholders see themselves reflected in their mutual interdependence in order to improve their interactions in the context of value creation for the organization.

2.5.3. A multifaceted approach with a strong HR emphasis

If IS governance can act in the interests of the stakeholders by recognizing their contribution and including them in the decision-making process, it can also pave the way to a closer relationship between the information systems management committee and HR. This might begin with the strategic development of an HRIS [CER 12], which, in turn, can influence IS governance in its entirety. Between individualization and collective management, HRIS management opens up new avenues for the governance. Its strength lies in its ability to reconcile the transversal nature of the project while bringing together the actors involved [MID 12]. In this model, governance fora will be defined by a comprehensive vocational matrix. All kinds of projects can benefit from this type of organization. They will be driven and serviced by the plurality of perspectives and skills. Of the three models mentioned, it is this last model that probably goes furthest in taking into account the importance of stakeholder interaction in value creation. This stakeholder governance model seems to offer the potential to unite the three approaches put forward, retaining the good practices, or nomadic practices, conveyed by the other two [STE 87].

2.6. Open innovation type software

If the dual strategy of transaction costs helped develop partnership strategies of pooling within organizations, the expansion of the IS issue to a larger number of actors paves the way for a radical transformation of our societies.

This transformation is not limited to digital issues. As the growth of the free or open-source software movement and the collaborative economy has shown us, ICT promotes the path towards redrawing the shape of collective action and redistributing operational roles.

Innovation steps outside organizations and moves ahead outside of them or between them. In this respect, we use the term “open innovation” when talking about procedures where businesses interact with private individuals within communities of practices. The world is changing, and with it, the classic face of the economy, which used to separate the producer figure from the consumer figure. Between markets and governments, between personal property and public property, a space is opening up for shared property and its governance.

2.7. Exercise: Bacchus

Bacchus was recently created from a collaboration between a wine merchant established in the big French towns and cities via a network of some 100 franchise stores under the brand and an online wine marketing/distribution website. Bacchus’ skills lie in the establishment and monitoring of ongoing relationships with producers in the great wine-producing regions of France and neighboring countries such as Italy and Spain, with whom Bacchus negotiates the purchase of high-quality wines, often “en primeur”, i.e. ahead of harvesting, on preferential terms. Prior to distribution, it lays them down until maturity in its warehouses in Gennevilliers, near Paris. Wines and vintages are then listed in Bacchus’ catalog, to be launched to the wine merchants on monthly tasting days. The wine merchants order cases of wine to add to the stock available from their retail outlets and sometimes available to be ordered and delivered directly to individuals and businesses for special occasions (celebratory events, seminars). In this case, Bacchus offers wine merchants a delivery service from the warehouse directly to the customer, with its fleet of delivery vehicles in the company livery. The wine merchants are free to set their selling price, but without exceeding a ceiling markup rate on the purchase price from the warehouse, and fixed in the franchise agreement. The core business activity is based on an integrated ERP-type system with three modules (accounting, finance and production monitoring). This solution thus enables the administrative, logistical and accounting processes to be handled. Its hosting is outsourced, together with its operation and maintenance, to an IT service provider specializing in SMEs. Each store has a till for the franchise, linked to the ERP. In addition to holding instore prices, the till handles the outlet’s stock control and customer records and has the ability to communicate with the central system. In total, more than 200,000 customers are recorded and followed up by the outlets as a whole, although customer loyalty is low at present. The average shopping basket instore is around €25 per checkout. Since Internet use became widespread, many websites selling wine directly from the estate have sprung up. These sites generally handle, at the request of the producers, or the merchants in the case of foreign wines, the marketing and retail sales of high-quality “crus” over a time-limited promotional period. Notification of these promotional events is accompanied by extensive tasting notes and includes comments from highly respected experts. There is enough information to form an opinion, but without being able to taste before you buy. The websites take orders online and then arrange delivery within a week, from the producer or the import warehouse to the customer’s home using a carrier specializing in single parcel deliveries. Bacchus acquired and then developed a website almost two years ago. This website is now established among the top French websites for online wine sales, and Bacchus has made a significant profit on its initial investment. More than 300,000 customers in France have already taken advantage of offers and given their address (postal and email), based on a shopping cart averaging €100 per visit. More than one-third were still active in the last 12 months. The development of the online shop was entrusted to a marketing agency before being hosted by an operator specializing in commercial websites for small businesses. Two young recruits at Bacchus’ offices are responsible for administration and updating the site. Bacchus’ boss continues to personally liaise with the marketing agency and has surrounded himself with a young team of managers who grew up with digital technology, in charge of prospecting producers and promoting the brand today, and of digitalized and integrated business development tomorrow. Encouraged by its early success, Bacchus now plans to strengthen its business model by extracting potential synergies from its two business activities, which will allow it to increase the quality and the speed of service, its market share and customer loyalty, to grow sales and to optimize costs, margins and working capital requirements, and finally to increase the size of its franchise network, in France and abroad. Bacchus is counting on your support for the company and the team in these plans.

Practice your skills

- 1) Which business model did Bacchus choose to adopt? To give a detailed answer, you should specifically highlight the value proposition to end clients, the value proposition made to franchises, the key partners and processes, the resources and skills, and the economic balances. What are the strengths of this business model?

- 2) The implementation of this kind of strategy based on IS raises certain risk levels. Can you explain what risks the technological strategy brings for Bacchus? How can the company mitigate or circumvent them?

- 3) Describe the governance model that seems to you the best to ensure the success of the Bacchus business model and Bacchus’ information system.